Weird Christianity In Covidtide

My pal Tara Isabella Burton, who is one of the most interesting religion writers today, has a piece in the NYT Magazine, which has posted it online in advance of weekend editions. It’s about “weird Christianity,” which she defines as follows:

More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present.

Many of us call ourselves “Weird Christians,” albeit partly in jest. What we have in common is that we see a return to old-school forms of worship as a way of escaping from the crisis of modernity and the liberal-capitalist faith in individualism.

Weird Christians reject as overly accommodationist those churches, primarily mainline Protestant denominations like Episcopalianism and Lutheranism, that have watered down the stranger and more supernatural elements of the faith (like miracles, say, or the literal resurrection of Jesus Christ). But they reject, too, the fusion of ethnonationalism, unfettered capitalism and Republican Party politics that has come to define the modern white evangelical movement.

Most of the people she interviewed for the piece are Millennials or younger, but she did talk to me too (I’m a Gen Xer). I had to laugh at the photo they used. The photographer took it in mid-February, when my hair was freshly cut, and my beard was short. I have neither cut my hair nor trimmed my beard since then, because of the lockdown. I’m starting to look like Grizzly Adams taking a graduate seminar in Hegelianism in Brno. Tara also interviewed my pal and Benedict Option practical genius Leah Libresco Sargeant, who said:

Leah Libresco Sargeant, a Catholic convert and writer who describes her views as roughly in line with that of the American Solidarity Party, which combines a focus on economic and social justice with opposition to abortion, capital punishment and euthanasia, rejects capitalist notions of human freedom.

“The idea of the individual as the basic unit of society, that people are best understood by thinking about them as sole lone beings” is fundamentally misguided, she told me. “It doesn’t make enough space to talk about human weakness and dependence” — conversations that she believes are an integral part of Christianity, with its concern for human life from conception until death.

That’s pretty much where I am politically, though I rarely write about economic policy. Here’s what I thought was the most interesting part of the TIB piece. “Garry” is John Garry, a college student and former alt-right guy who converted to Christianity via Weird Catholic Twitter, and now identifies as a Christian Marxist; “Crosby” is Ben Crosby, an Episcopalian seminarian:

It is unclear what the world will look like when the coronavirus pandemic, at last, comes to an end. But for these Weird Christians, this crisis doubles as a call to action. For Mr. Garry, the former Breitbart contributor, it has made plain “the absolute dearth of mutual aid in America.” Christianity, he told me, “compels us not just to take care of people around us but to seek to further integrate our lives and fortunes into those of the people around us, a sort of solidarity that necessarily entails creating these organizations to help each other.”

Mr. Crosby agrees. The pandemic, he said, has made all too clear that both liberal and conservative visions of American life, based on “self-fulfillment via liberation to pursue one’s desires” is not enough. “It turns out we need each other,” he said, “and need each other dearly.”

What Christianity offers, he added, is “a version of our common life more robust than individual pursuit of desire-fulfillment or profit.” In the light of that vision, the current pandemic can “be both a cross to bear and an opportunity to reflect the love that was first shown us in Christ.”

If Garry is calling himself a Marxist, then I cannot imagine that his politics and mine overlap much, but I think he’s quite correct in talking about “the absolute dearth of mutual aid in America.” I really identify with Crosby’s remarks about the failure of liberal and conservative visions of American life. As I’ve been saying here for weeks now, this virus really is an “apocalypse” in the sense of an unveiling. We get to see who we really are. A lot of it is ugly. The cost of social atomization — something that has been driven by many factors in American life since the end of World War II; you cannot blame it wholly on the left or the right — is making itself known. Our political leadership is poor, but so is our followership. I don’t see much of a sense of solidarity of any kind.

Can you really look to the churches for that — I mean, the churches as they are today? To be fair, nobody alive today has ever had to deal with anything like this, and it is extremely difficult for churches to do what they are used to doing when we have to live under such strict practices to avoid infecting each other. Still, I see this Covidtide to be a massive call to repentance for all of us. If we Christians had been living and praying and thinking like Christians — if our churches had discipled us, and if we had wanted to be discipled, instead of merely comforted — we wouldn’t be in such a mess today, facing this crisis.

I’m feeling this pretty acutely now because I’m winding up final edits and rewrites of my next book. That has meant spending more time with the stories and testimonies of believers who endured persecution under Soviet communism. Just today I was re-reading the transcript from my interview in Moscow last fall with Yuri Sipko, an older man who is an ordained Russian Baptist pastor, and who grew up in a heavily persecuted Russian Baptist community. Here are a couple of excerpts from the interview:

How did I find the strength to resist? I don’t know. We had a specific atmosphere in our family. I’m one of 12 kids. My older brothers and sisters had already gone through this. My father was the pastor of our congregation. All sorts of pressure was put on him. When I was a child, all I knew was that I wanted to be like my father. I could see that he had certain positions, and I saw that he was able to stand alone, against all of this pressure against him. He was able to stand up with dignity and courage. I wanted to be like him.

I was probably 10 years old when they first brought charges against him, and sentenced him for five years, for preaching. They sent him to prison in eastern Siberia for five years. I ended up not finishing school. I left in ninth grade, at 16 years old.

More:

Without being willing to suffer, even die for Christ, it’s just hypocrisy. It’s just a search for comfort. When I meet with brothers in faith, especially young people, I ask them: name three values as Christians that you are ready to die for. This is where you see the border. I don’t even value my life as much as my mission.

When I think about the past, and how our brothers were sent to prison, and never returned, I’m sure that this is the kind of certainty they had. They lost any kind of status, they were mocked and ridiculed in society. Sometimes they even lost their children. Just because they were Baptists, [the state was] willing to take away their kids and send them to orphanages. They were unable to find jobs. Their children were not able to enter universities. To get to universities you had to take an exam in scientific atheism. A believer could not pass this exam. But at least the battle was clear then. Today the truth has become blurry. The sharpness of this battle is not clearly defined.

What I would say to my Christian brothers in America is that you need to return Christ to the pedestal of your heart. You need to confess him and worship him in such a way that people can see that this world is a lie. This is difficult, but this is what makes man an image of God. As Christ said, “I am in the Father and the Father is in me. He who follows me will have eternal life.” If in our current life today, we’re leaving Christ over on the side, then we have a godless life.”

In Russia, as in the Soviet Union, it’s very weird to be a Baptist. But there is Yuri Sipko, completely fearless.

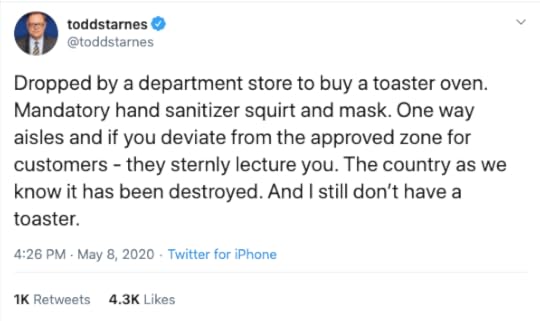

Tonight, as I finished work on a chapter featuring some of Sipko’s storytelling, I checked Twitter, and found this comment from Todd Starnes, a Southern Baptist #MAGA media personality:

A stern lecture. And no toaster for you! I mean, honestly.

If you think I’m holding myself up as better than Starnes, you’re wrong. I’m just as fat and coddled and as privileged as he is. If I have any advantage over him, it’s that the experience of sitting with brave souls like Yuri Sipko, and hearing their stories, was intensely convicting. Most of us American Christians have never been put to the test like the believers living under communist totalitarianism were. Many of us have never even been put to the test of sustained poverty. If you are like me, a middle-class Christian, don’t be sure at all how you would react if real persecution came. I’ll tell you this, though: if we can’t get through a pandemic that has killed almost 80,000 Americans in the past ten weeks, and put 34 million Americans out of work, without whining about our shopping experience being disturbed — well, what are we going to do if real persecution comes?

In Moscow, on the same day that I interviewed Sipko, I had dinner with Alexander Dvorkin, an academic who is an expert on cults. In talking about the potential for a new totalitarianism, he warned that a society in which there is a great deficit of solidarity is one that is prone to capture by a cultish mass leader. “There is a danger that the desire to belong will prevail over truth,” he told me. “All revolutions are carried out by people who have found [in their ideology] a strong sense of belonging.”

One way or another, Americans are going to rediscover a sense of belonging. The pandemic and the economic depression is revealing the radical insufficiency of our way of life — and, I would emphasize for my fellow Christians, the radical insufficiency of our way of Christian living. We need “weird Christianity,” in the sense of a deep and rooted Christianity that is countercultural. To be a countercultural church in America today is to be a church that practices solidarity, and is preparing its people to suffer the loss of status, the loss of material possessions, and maybe even the loss of freedom. To be a countercultural Christian in America today means being radical.

I am an Orthodox Christian. I wish you would become one too. But joining an Orthodox parish — or a Catholic one, or an Anglican one, and so on — is not going to be enough. Yuri Sipko is a Baptist, which is about as far away from Russian Orthodoxy as you can get. But that man has within him what it takes to endure. It was placed there by his family, and the community in which he was raised. It came from his churching.

I can’t say enough about what God has done for me through the prayers, the liturgies, and the spirituality of Orthodox Christianity. It is pretty weird in America, and thank God for that. One of the most important things is finally getting it through my thick head that all of that “weird Christian” stuff is about breaking down the barriers between the self and God. That the Christian life is about constant repentance. I don’t mean that it’s always sorrowful; joy and feasting is also central to the authentic Christian life. But the Christian life is a constant pilgrimage of inner conversion, of dying to self, and of awakening to yourself as a new creation. I’m sorry to be all preachy here, but this past year of reading stories about Christian life under communist totalitarianism, and talking to older men and women who lived through it, has been for me, as a comfortable middle-class American Christian, a call to repentance.

I’m not sure what that is going to look like when this coronavirus plague passes. I’m not sure what that’s going to look like in two or three months, when it hasn’t passed, but we have to find some way to live so we can feed ourselves. I do believe, though, that God is calling all of us Christians to walk away from our soft, gripey, self-centered way of living, individually and as a community. He always has been doing that, but now, this crisis could be a special mercy, given to wake us up to the true condition of our souls.

Politics of the left or the right is not going to save us. It might help somewhat, but what needs healing in this country is deeper than politics. Shallow, emotional religion won’t save us either — but don’t be deceived into thinking that getting a prayer rope, or praying in Latin on Sunday morning, will do the trick, unless it all leads to conversion of the heart. A lesson that I still struggle with, almost 14 years after becoming Orthodox: the prayer rope is meaningless if it stays wrapped around your wrist; it only works if you pass it through your fingers (which is to say, it’s only useful if it helps you actually to pray).

OK, sermon is over. I’ve been hearing from some of you Christian readers who have been sending me stuff you’ve taken off social media from your Christian friends. It’s depressing — the paranoia, the conspiracy theories, the people giving themselves over to political fantasies that stoke their freakout, rather than help them to build spiritual and moral resilience for the long, difficult road ahead. One reader said to me that she was planning to quit Facebook, because she can’t stand to see people — fellow Christian people — she knows and loves saying crazy things, and ugly things, out of a spirit of fear and rage. I’m not on Facebook myself, but it might not be a bad idea to do the weird, un-American thing, and quit Facebook for the good of your soul.

What do you readers think? What could “weird Christianity” do for the broader church? What qualifies as “good weird,” and what qualifies as “bad weird”?

The post Weird Christianity In Covidtide appeared first on The American Conservative.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers