Stephen Theaker's Blog, page 7

October 25, 2024

Kaijumax, Season Two, by Zander Cannon (Oni Press) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).Kaijumax is a prison island for kaiju (giant monsters), a lot like the one in Destroy All Monsters, one of the greatest films of all time. Fans of the Godzilla films and their like will see lots of fun references to them, from the use of giant mecha to fight them down to using little round monster icons on the cover, like those on Godzilla dvds. Season one looked adorable but was in places extremely grim, even for those of us who got through all of Oz. I bought every issue as it came out, so it didn’t put me off, but be warned that the series is totally unsuitable for children – which is a shame because they would love the art. As the author accurately said in a season one letters page, it has “a cartoony style, a jokey high concept, a pitch-black sense of humour, and an undercurrent of dread”. A note at the back of this book expands on the author’s thinking about the book, giving the impression that people have taken issue for example with the slang the monsters use, which can risk sounding like a parody of African-Americans. He admits that the book leans on stereotypes, but asks readers to bear in mind its preposterous premise.

Season two, which lasts for six episodes (or issues), looks at how the outside world intersects with the prison, through employees and escapees. We are reminded by a memo – addressed to the Council of Light, Nebula of the Eternal Sunrise, with Commissioner Singh of Science Police Team Great copied in – that Electrogor (who had an awful time in season one) and the Green Humongo used a nuclear explosion to escape from Kaijumax. Electrogor just wants to get back to his kids, who have been left to fend for themselves for too long. The Green Humongo wants to hang with his brother. Another storyline follows the relationship of robot Chisato and Jin-Wook Jeong, a man in a giant robot suit. It’s all goofy, exciting and emotional, and it’s always looking to explore the areas implied but untouched by the Godzilla films, making it absolute catnip for fans. There are lots of new giant monsters to enjoy, as well as an utterly unique version of the Lovecraft mythos and a take on Gamera that dials the pathos up to eleven. The book takes something that I enjoy because it’s daft, and tries to make it into something truly affecting. More often than not it succeeds. Stephen Theaker ****October 21, 2024

Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between VII: Appendix – Rafe McGregor

The seventh of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by first exploring thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post provides notes on a new series from theBritish Library, the cases of Kyle Murchison Booth, and the Southern Reach Quartet.

The Weird Tale: The British Library Tales of the Weird

Somewhat to my shame, I only discovered the British Library series while researching this series of posts. I really should have seen it sooner as it hasbeen going since 2018 and published fifty-three titles to date (roughly one amonth). The books are all sturdy paperbacks, with colourful, imaginative, and attractivecovers and spines and cost £10 or less, depending on where and how one buysthem. Each instalment includes a ‘Note from the Publisher’, which serves as acombined trigger warning and ethical rationale and which I reproduce here as exemplarypractice:

The original short storiesreprinted in the British Library Tales of the Weird series were written andpublished in a period ranging across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.There are many elements of these stories which continue to entertain modernreaders; however, in some cases there are also uses of language, instances ofstereotyping and some attitudes expressed by narrators or characters which maynot be endorsed by the publishing standards of today. We acknowledge thereforethat some elements in the stories selected for reprinting may continue to makeuncomfortable reading for some of our audience. With this series BritishLibrary Publishing aims to offer a new readership a chance to read some of therare material of the British Library’s collections in an affordable paperbackformat, to enjoy their merits and to look back into the worlds of the past twocenturies as portrayed by their writers. It is not possible to separate thesestories from the history of their writing and as such the following stories arepresented as they were originally published with minor edits only, made forconsistency of style and sense.

My only complaint, which prompted me to include this part of the appendix,is that there are no numbers on or in the books, meaning that it isn’t easy toread them in order. I’m sure there is a sound reason for this editorialdecision, but all collectors and some readers will want a chronological list.There’s one on Medium compiled by Owen Williams, which is easier tonavigate than the British Library’s and which I used as a guide in compiling myown:

From the Depths and Other Strange Tales of the Sea Haunted Houses: Two Novels by Charlotte Riddell Glimpses of the Unknown: Lost Ghost Stories Mortal Echoes: Encounters With the End Spirits of the Season: Christmas Hauntings The Platform Edge: Uncanny Tales of the Railways The Face in the Glass and Other Gothic Tales by Mary Elizabeth Braddon The Weird Tales of William Hope Hodgson Doorway to Dilemma: Bewildering Tales of Dark Fantasy Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic Promethean Horrors: Classic Stories of Mad Science Roarings from Further Out: Four Weird Novellas by Algernon Blackwood Tales of the Tattooed: An Anthology of Ink The Outcast and Other Dark Tales by E.F. Benson A Phantom Lover and Other Dark Tales by Vernon Lee Into the London Fog: Eerie Tales from the Weird City Weird Woods: Tales from the Haunted Forests of Britain Queens of the Abyss: Lost Stories from the Women of the Weird Chill Tidings: Dark Tales of the Christmas Season Dangerous Dimensions: Mind-Bending Tales of the Mathematical Weird Heavy Weather: Tempestuous Tales of Stranger Climes Minor Hauntings: Chilling Tales of Spectral Youth Crawling Horror: Creeping Tales of the Insect Weird Cornish Horrors: Tales from the Land’s End I Am Stone: The Gothic Weird Tales of R. Murray Gilchrist Randalls Round: Nine Nightmares by Eleanor Scott Sunless Solstice: Strange Christmas Tales for the Longest Nights The Shadows on the Wall: Dark Tales by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman The Ghost Slayers: Thrilling Tales of Occult Detection The Night Wire and Other Tales of Weird Media Our Haunted Shores: Tales from the Coasts of the British Isles The Horned God: Weird Tales of the Great God Pan Spectral Sounds: Unquiet Tales of Acoustic Weird Haunters of the Hearth: Eerie Tales for Christmas Nights Polar Horrors: Strange Tales from the World’s Ends The Flaw in the Crystal and Other Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair The Ways of Ghosts and Other Dark Tales by Ambrose Bierce Holy Ghosts: Classic Tales of the Ecclesiastical Uncanny The Uncanny Gastronomic: Strange Tales of the Edible Weird The Lure of Atlantis: Strange Tales from the Sunken Continent Dead Drunk: Tales of Intoxication and Demon Drinks The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson Roads of Destiny and Other Stories of Alternative Histories and Parallel Realms Circles of Stone: Weird Tales of Pagan Sites and Ancient Rites Doomed Romances: Strange Tales of Uncanny Love The Undying Monster: A Tale of the Fifth Dimension by Jessie Douglas Kerruish Fear in the Blood: Tales from the Dark Lineages of the Weird Out of the Past: Tales of Haunting History The Night Land by William Hope Hodgson Deadly Dolls: Midnight Tales of Uncanny Playthings The Human Chord by Algernon Blackwood Eerie East Anglia: Fearful Tales of Field and Fen The Haunted Trail: Classic Tales of the Rambling WeirdThere are three more titles due for publication, all by the end of this year: The Weird Tales of Dorothy K. Haynes The Haunted Vintage by Marjorie Bowen Summoned to the Séance: Spirit tales from Beyond the Veil

The Occult Detective Story: Kyle Murchison Booth

In parts III and IV of this series, I praised Sarah Monette’s Kyle Murchison Booth occult detective stories andmentioned that some are, unfortunately, difficult to find. The eighteen storieshave been published over a period of twenty years (2003-2023), during which twobooks have been published: The Bone Key: The Necromantic Mysteries of KyleMurchison Booth (2007; second edition, 2011), a collection of ten shortstories, and A Theory of Haunting (2023), a novella and the most recentstory. This is a chronological list of all eighteen, with the original date ofpublication in parenthesis and my suggestion for the easiest way to find them… The Wall of Clouds (2003) – The Bone KeyThe Venebretti Necklace (2004) – The Bone KeyThe Inheritance of Barnabas Wilcox (2004) – The Bone KeyBringing Helena Back (2004) – The Bone KeyThe Green Glass Paperweight (2004) – The Bone KeyWait for Me (2004) – The Bone KeyElegy for a Demon Lover (2005) – The Bone KeyDrowning Palmer (2006) – The Bone KeyThe Bone Key (2007) – The Bone KeyListening to Bone (2007) – The Bone KeyThe World Without Sleep (2008) – Somewhere Beneath ThoseWavesThe Yellow Dressing Gown (2008) – ApexThe Replacement (2008) – Sarah MonetteWhite Charles (2009) – ClarkesworldTo Die for Moonlight (2013) – ApexThe Testimony of Dragon’s Teeth (2018) – UncannyThe Haunting of Dr. Claudius Winterson (2022) – UncannyA Theory of Haunting (2023) – A Theory of Haunting

…I only hope that there are many more to come.

The Ecological Weird: Absolution

Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy – consisting of Annihilation,Authority, and Acceptance, all published in 2014 – becomes aquartet tomorrow, with the UK release of Absolution in hardback, paperback,Kindle, and Audible. My original intention for this appendix was to provide asynopsis or summary of the trilogy for those who might not want to reread allthree books before starting the fourth, but nonetheless need a reminder of the sequenceof events. (This is what I wanted, in spite of having read the trilogyseveral times and having no doubt that I would return to it and the quartet in future.)To cut a long story short, I failed dismally, and will poach Mac Rogers’ reason: ‘There’s really noway to give the Southern Reach pitch without sounding high, soI won’t try.’ I do, however, recommend the first part of Adam Roberts’ review of the trilogy,which provides the best summary I could find with limited spoilers. (The secondpart is also worth reading, although it’s more interpretative thandescriptive.) There was chatter some time ago about a prequel to the SouthernReach and it’s not quite clear whether Absolution is a prequel,sequel, paraquel, or some combination of these categories(reminding me of Heat 2, which nearly ruined one ofmy favourite films). Here is what VanderMeer himself has to say on his website:

Ten years after thepublication of Annihilation, the surprise fourth volume in JeffVanderMeer’s blockbuster Southern Reach Trilogy.

When theSouthern Reach Trilogy was first published a decade ago, it was an instantsensation, celebrated in a front-page New York Times story beforepublication, hailed by Stephen King and many others. Each volume climbed thebestsellers list; awards were won; the books made the rare transition frompaperback original to hardcover; the movie adaptation became a cult classic.All told, the trilogy has sold more than a million copies and has secured itsplace in the pantheon of twenty-first-century literature.

And yet for all this, for Jeff VanderMeer there was never full closure to thestory of Area X. There were a few mysteries that had gone unsolved, some keypoints of view never aired. There were stories left to tell. There remainedquestions about who had been complicit in creating the conditions for Area X totake hold; the story of the first mission into the Forgotten Coast—before AreaX was called Area X—had never been fully told; and what if someone had foreseenthe world after Acceptance? How crazy would they seem?

Structured in three parts, each recounting a new expedition, there are somelong-awaited answers here, to be sure, but also more questions, and profoundnew surprises. Absolution is a brilliant, beautiful, and ever-terrifyingplunge into unique and fertile literary territory. It is the final word on oneof the most provocative and popular speculative fiction series of our time.

I’m not sure that either more closure or more exposition are required or willenhance the trilogy as it stands, but I am confident that VanderMeer won’t ruinthe masterpiece he created a decade ago. So far, there have been surprisinglyfew advance reviews: Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, and Scientific American.

More Recommended Reading

Fiction

John Hall (ed.), Five Forgotten Stories (2011).

Rafe McGregor, Eight Weird Tales (2024).

Rafe McGregor, Six Strange Cases (2024).

Nonfiction

Stephen Ellcock & Mat Osman, England on Fire: A VisualJourney through Albion's Psychic Landscape (2022).

Mark Valentine, The Thunder-Storm Collectors (2024).

Timothy Murphy, William Hope Hodgson and theRise of the Weird: Possibilities of the Dark (2025).

October 18, 2024

Shoot at the Moon, by William F. Temple (The British Library) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review was originally written for a previous iteration of the British Fantasy Society's website, and then appeared in TQF65 (December 2019).

This review was originally written for a previous iteration of the British Fantasy Society's website, and then appeared in TQF65 (December 2019).Part of the British Library Science Fiction Classics range, this enjoyable novel about an ill-fated trip to the moon dates from 1966. Mike Ashley provides an introduction, and it is fascinating – we learn that this novel was very nearly adapted into a Hollywood film – but read it after the novel to save the book’s surprises.

The protagonist and narrator is Captain Franz Brunel, a Londoner and a space pilot. Like all the men in this book, he doesn’t like women very much. He doesn’t like anyone else for that matter, being a self-identified misanthrope, but the way he talks about women in particular will be enough to put some readers off the book entirely. It’s tempting to describe him as hard-boiled, and there is a strong element of that genre to the book as the mysteries develop, but inside his shell Franz is rather runny: he’s filled with doubts about his future, decisions, skills, age, relationships and this job: if the automated piloting system on the ship is a success, they won’t need space pilots any more.His femme fatale is Lou, daughter of Colonel Marley, the bumptious and aggressive gentleman organising the lunar jaunt. She’s along for the trip too, in her own right as a distinguished scientist. A friend of Franz describes her as “a fine male mind functioning in a fine female body”, which gives a taste of the sexism to expect from these chaps. Franz’s feelings for her become as complicated as her personality. Also on board are Pettigue, a cowardly scientist whose past breeds distrust, and Doctor Thomson, a bully with a mean sense of humour – described by Franz with typical misogyny as having “an almost feminine pleasure in stabbing people in the back”.

Brunel quotes a maxim attributed to Lord Mountbatten – “a happy ship is an efficient trip” – and the novel explores the converse idea. Imagine Journey into Space if the crew hated each other all the time, not just when under the influence of aliens. It is, as Franz puts it himself, “like the cast list of one of Sartre’s more cannibalistic plays”. He probably had something like Huis Clos in mind. But a pleasant surprise was that this didn’t end up being just a locked-room mystery in an unusual location. The characters do get out and about on the moon, and they make some intriguing discoveries there.

Though we know now a bit more about the moon than we did in 1966, the book has lost surprisingly little of its relevance, starting as it does on a world where automation leaves increasingly fewer ways to make a living, and some people spend all day playing games. And when the obnoxious, wealth-obsessed Colonel Marley declares in a speech that, “You’re as right or wrong as you believe yourself to be”, he sounds ever so much like the modern demagogues and social media tub-thumpers who don’t care whether what they say is true or not.

The frequent sexism is undoubtedly off-putting, and I completely understand the negative reactions that has provoked from some readers. But I don’t think the reader is at all being asked to admire these awful characters. Even in our protagonist the sexism is shown as a serious character flaw which stands between him and happiness. If you can get past that, as he tries to do, the book is full of revelations and twists and character, and has many good lines. “I can tolerate my own bad manners but not other people’s,” declares Franz. And upon first meeting Colonel Marley, he says, “I’m sure we’ll get along fine. Sure as today’s Tuesday.” To which Marley replies, after a pause, “It’s Wednesday.” Stephen Theaker ****

October 17, 2024

#OcTBRChallenge 2024: a second A to Z of books and audiobooks

I'm taking part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I'm trying to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I can, in A to Z order. It's been very good fun. My first A to Z of the month is here.

I'm taking part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I'm trying to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I can, in A to Z order. It's been very good fun. My first A to Z of the month is here.A is for Abominable, a novella by William Meikle. A lost journal of George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine from 1924 is offered for sale. It records their final, fatal ascent of Mount Everest, when they encountered something abominable! With a mouth full of long yellow teeth!

B is for Broken Glass, an audiobook of Arthur Miller's play about a Brooklyn woman in 1938 who, terrified by news of Jewish businesses being smashed up in Berlin, loses the ability to walk. Wonder what she'd make of the same thing happening now in New York. Stars JoBeth Williams. It was staged by LA Theatre Works in 1996. Included in Audible Plus for free.

C is for Creepy Comics, Vol. 1, by various writers and artists, Dark Horse's resurrection of the old horror anthology comic. Found this a trudge, to be honest, with inconsequential, simplistic stories and muddy artwork that was often hard to parse.

D is for The Dark Knight Returns: The Golden Child, by Frank Miller and Rafael Grampa. Bit weird this, originally published as issue 1, but no other issues materialised so now it's published as a book in itself. Batman Cassie Kelly and Superman's kids get into a fight with Darkseid.

E is for Emergency Skin by N.K. Jemisin, the first thing I've read by her, and a Hugo winner, apparently. An agent sent from a colony expects to find Earth in ruins, but in fact it became a utopia after the nasty capitalists fled. A bit cringey, but how they treat him is sweet.

F is Fabius Bile: Repairer of Ruin by Josh Reynolds. I know I'm trying to finish my shortest books and audiobooks, but at only twenty minutes this audiobook is an extreme example! It recounts a skirmish on a demon world in the Warhammer 40K universe. Great sound effects and performances!

G is for Gallifrey 1.2: Square One, by Stephen Cole, starring Lalla Ward, Louise Jameson and John Leesons. I'd forgotten that I bought over a dozen of these audios a couple of years ago and they are quite a treat. This one concerns time trickery at a temporal summit, at which Leela goes undercover as an exotic dancer.

H is for Hellblazer: Rise and Fall, written by Tom Taylor with art by Darick Robertson. Ouch, painful. Makes the New 52 issues look good. I suppose English police officers might carry guns in the DC universe, but I think Hellblazer writers from outside the British Isles do best when setting their stories in their own countries.

I is for Is Kichijoji the Only Place to Live? by Makihirochi, a gentle manga about twins who took over their parents' estate agency, and run it in an unconventional manner, which always seems to involve persuading their clients not to live in Kichijoji, but elsewhere in Tokyo.

J is for The Judge's House by Georges Simenon. Maigret is present during a judge's attempt to dispose of a body. Typical Maigret tale full of grub and grubbiness. Modern-day readers may be surprised at how one chap gets away with what would now be considered a serious crime. We're supposed to feel sorry for him, if anything!

K is for Ka-Zar, Vol. 1, a Tarzan in Marvel's version of New York story by Mark Waid, with art by Andy Kubert and others. I remember this being well-regarded at the time, but it's not easy to see why now. The art is wildly dynamic, but not always to the storytelling's benefit.

L is for The Lover by Silvia Morena-Garcia, a short ebook/audiobook about Judith, a young woman treated as a servant by her more beautiful sister. She dallies with a pair of men, one who gives her books in return for sexual favours, the other her sister's husband.

M is for Melody James by Stephen Gallagher, an intriguing novella about a clever, resourceful fortune-teller recruited in 1919 to vet a journalist, a potential spy for the British secret service in Soviet Russia. Spin-off from a novel, The Authentic William James.

N is for November, Vol. 1: The Girl on the Roof, by Matt Fraction and Elsa Charretier. A stylish and mysterious graphic novel about a dissolute young puzzle fanatic who is paid $500 a day to solve a puzzle in the paper and broadcast the solution from a radio set on her roof.

O is for O Maidens in Your Savage Season, Vol. 1, written by Mari Okada, trans. Sawa Savage, with art by Nao Emoto, a manga book about romantic tension and teenage hormones boiling over in the school book club. It's funny and sweet but gets a bit ruder than expected in places.

P is for Put to Silence by Rose Biggin, a short, tart ebook published by Jurassic London in 2014 about a murder attempt during a performance of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. The target's Brutus, the client's playing Julius Caesar, the killer's in the chorus.

(I decided not to count it for my A to Z in the end, but for P I also read an excellent novella that will hopefully appear in our twentieth anniversary issue of our magazine. It's the latest story in a long-running series. My favourite thing I've read this month, honest!)

Q is for Queen Crab, a short graphic novel by Jimmy Palmiotti and Artiz Eiguren. On my TBR list since January, when I got it in a Humble Bundle. The tale of a woman betrayed – after a scoundrel tries to drown her on a cruise, she mysteriously gains a pair of powerful crab claws!

R is for The Roman Empire, a Very Short Introduction, by Christopher Kelly, read by Richard Davidson. Explains how the Roman Empire was built, and banishes many illusions about it. Weird to learn that present-day Britain has a higher population than the entire Roman Empire. It looks like these are all leaving Audible Plus this month so I want to listen to a few of them for free while I still can.

S is for Stag by Karen Russell, read by Adam Berger. A lone wolf type of guy attends a divorce party with a one-night stand, and as things take a more serious turn at the previously silly party, he becomes rather obsessed with the divorcing couple's pet tortoise.

T is for Trigger Girl 6, thus named because she's the sixth mysterious super-powered assassin sent to kill the President of the USA. Written by Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray, with very nice art by Phil Noto. Feels more like a French BD album than a traditional American comic.

U is for Ushers by Joe Hill, one of my Amazon First Reads picks this month. Two police officers chat with a young man in a bookshop (where he buys 4000 Weeks by Oliver Burkeman) because he went home before a school shooting happened and got off a train that subsequently crashed.

V is for Venom by Donny Cates, Vol. 1: Rex, with pencils by Ryan Stegman. Eddie Brock learns about the symbiote's cosmic origins. The reason given for Venom's vulnerability to sound and fire was very silly, but there was some cool stuff too; overall the best Venom book I've read.

W is for Wild With Happy, the audiobook of a superb play from writer, director and star Colman Domingo, who plays Gil Hawkins, dealing (or not) with his mother's death by getting off with the funeral director and foregoing any ritual, much to the dismay of his hilarious aunt.

X is for X-Men Grand Design: Second Genesis by Ed Piskor, which pulls together a decade's worth of X-Men issues into one indie-style graphic novel. My 50th book or audiobook of the month! Jamming all these stories – not to mention all the fantastic TQF submissions I've been reading! – into my head at once is making me a little dizzy.

Y is for Yee-Haw: Weirdly Western Poems by Rhys Hughes. Of poetry I know not much, but what my mother said / "Books by that wacky Welshman, must not be left unread!" My favourite bit was a short Samuel Beckett-ish play, "Uneasy Rider", featuring author Max Brand.

Z is for Zero Gravity by Woody Allen, his fifth book of comedic essays and stories. The ideas, writing and jokes are as strong as ever, but the audiobook sounds like it was recorded at the kitchen table! It's almost unlistenable at first, but gets better later on.

Second A to Z complete!

October 14, 2024

Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between VI: Exploring the Ecology Within – Rafe McGregor

The sixth of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by first exploring thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post introduces the register of the Real.

Hearts of Darkness

Notwithstanding very fine examples by China Miéville, Caitlín R. Kiernan,and M. John Harrison, the most critically and commercially acclaimed novel inwhat is usually called the new weird and I am calling the ecological weird isalmost certainly Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014), which is the first of hisSouthern Reach Trilogy (which will be a quartet later this month) and was successfully adapted to a feature film of the same name by Alex Garland in2018 (poster pictured). I do not intend to summarise or review either Annihilationor the Trilogy here, because excellent reviews and review essays havealready been published in The New Yorker, Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, Textual Practice, and elsewhere. Instead, Iwant to sketch a literary (and cinematic) lineage for Annihilation inorder to shed light on the definition of ecological weird fiction with which Iclosed part V. The ecological weird, like occult detective fiction, shares theprimary features of weird fiction by exploring the limitations of language, theinaccessibility of the world, and the alienation within ourselves. The last ofthese is particularly important for and to the ecological weird (to the extentthat it does or does not constitute a subgenre or subcategory of the weird) andis a development of the inaccessibility of the world (which I explained interms of the world-without-us in part IV). In ecological (and other) weird fiction,we not only encounter the alien, but recognise it within ourselves and eitherresist or accept it (it is no coincidence that the third part of the SouthernReach is titled Acceptance).

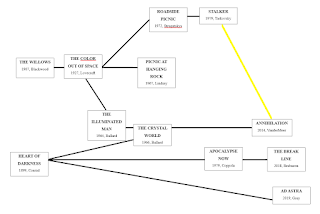

I have, in consequence, represented what I take to be the lineage fromwhich Annihilation emerged in a schematic (pictured). The link to J.G.Ballard’s The Crystal World (1966) and, by extension, to ‘TheIlluminated Man’ (published in Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1964),H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘The Color Out of Space’ (published in Weird Tales in 1927),and Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Willows’ (published in his collection, TheListener and Other Stories, in 1907) is uncontroversial. The Crystal World is a revision and expansion of ‘The Illuminated Man’ and Ballardappears to have deployed formal (and substantive) elements of Joseph Conrad’smasterpiece, Heart of Darkness (1899), in the course of adapting his ownwork. There are two points to note about this lineage. First,the inclusion of ‘The Willows’, which is – as I noted in part I – widelyacknowledged as the single best weird tale ever written, demonstrates that thethemes explored by the ecological weird are not new to the genre, merelydeveloped in a different format (typically the novel rather than the shortstory). Second, Heart of Darkness draws attention to the crux of theecological weird: it is not only about the (encounter with the) alien and (our)alienation, but self-alienation. Though criticised for its use of language and adoption of attitudes that are now, with complete justification, regarded as offensive, the novella provides a critique of colonialism so robust that it would keep plenty of social media trolls busy for a long time (assuming they had the intelligence and patience to read it). Conrad’s insightis that colonialism is not only bad for the colonised, who suffer what we wouldnow call genocide, but also for colonisers, for whom the remoteness and expansiveness of the colonies facilitates the flourishing of all that is vicious within them.Despite VanderMeer’s repeated and vehement denials that Andrei Tarkovsky’s featurefilm, Сталкер (1979, translated as Stalker),had any influence on Annihilation, I made a tenuous link in my sketch onthe basis of both narratives being concerned not only with a place that isutterly alien to humanity, but with the effects of that place on the minds ofthe people who enter it. The latter is essential to the ecological weird, the recognition of the alien within ourselves to which we respond with eitherresistance or acceptance.

The Weird Within

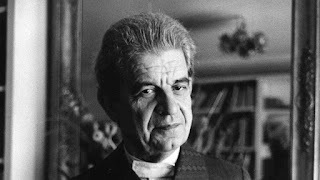

Psychoanalyst and philosopher Jacques Lacan (1901-1981, pictured) is aneven more controversial figure than Jacques Derrida (whom I discussed in partII) because he is regarded by many as a cynical (rather than sincere) charlatanand because there remains no consensus on the value of the vast body of work heproduced over a career of five decades. In contrast to Derrida (and EugeneThacker, discussed in part IV), I make no pretence to understanding Lacan’soverall project or even his individual publications and seminars, but I dothink that what is known as his register theory is useful for graspingthe self-alienation typically explored by and in ecological weird fiction. Registertheory is an account of the modes of human existence and, hence, an ontology (astudy of what exists, the way in which existing things exist, and how best toclassify and codify existing things). As an ontology, register theoryidentifies three distinct but intervolved modes of human experience or orders:reality that can be perceived, reality that is socially constructed bylanguage, and reality that remains inaccessible. The Imaginary refers tothe world that human beings understand perceptively and non-reflectively and tothe way in which human beings understand both that world and themselves asinfants, i.e. before they develop the capacity for language. The Imaginary is thereforean innocent and naïve mode of human experience in which human beings arereduced to their perceptual capacities.

The Symbolic refers to the socially constructed world,which human beings access by means of language. The rules of the Symbolic order are revealed by theinvestigation of the way in which both language and social relations functionand Lacan draws on the classic structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure, whom Iintroduced in my discussion of Derrida in part II, and Claude Lévi-Strauss, aFrench anthropologist. The Symbolic cannot be grasped in its entirety, with theresult that human beings remain unaware of structures, contexts, and exchangeswhich have a profound influence on their lives. The Real refers to theineffable world, which is detectable by human beings indirectly through theunconscious. The ineffable transcends expression and exceeds language, making it very difficult to discuss and impossible to apprehend. The Real cannonetheless be conceived as an objective reality that is inaccessible tosubjective and intersubjective perception and cognition, a kind of Kantian noumenonor thing-in-itself (see part IV). The primary means of conceiving the Real isthe unconscious, which is why register theory is a significant component inLacan’s metapsychology. What makes the threeorders or registers useful for understanding the ecological weird is that they arenot only a taxonomy of the types of thing that exist but also structure thepsyche, i.e. human subjectivity. The structure of subjectivity thus consists ofall three of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real and the Real is thealien – or weird – within, the part of ourselves that is impossible toapprehend and can only be conceived partially and indirectly.

Future Weird

Weird fiction is thriving. Perhaps not quite as much as in its heyday,almost exactly a century ago, but probably in a healthier condition given thatit is no longer tied to and dependent on a single format (the short story) orthe success of a particular outlet (Weird Tales). I want to close thisseries with a couple of observations that draw on my short-lived but veryenlightening (for me, if not my students) stint as a creative writing tutor. In part V, I discussed the importance of thedevelopment of the weird novel to the survival of the genre in the twenty-firstcentury, citing S.T. Joshi’s discussion of the trend in what he terms the modern weird tale. Joshi identifies threeways in which authors have attempted to match literary intention withcommercial demand by extending the tale to the novel:

1. Writing a fantasticnarrative that has a real-world setting.

2. Writing a mystery narrativewith supernatural element.

3. Writing a narrative that isstructured around a complex supernatural situation.

He regards the first of these as difficult, although Harrison’s TheSunken Land Begins to Rise Again (2020) shows how it can be achieved. Thesecond is cheating in Joshi’s opinion and while I might agree if thesupernatural element is superficial or gratuitous, I think the greater concernis that crime fiction itself is better suited to the novella format (asmentioned in part V). Nevertheless, Miéville and VanderMeer both show how thiscan be achieved (without cheating) with The City & the City and Finch:A Novel, both published in 2009. The third is Joshi’s recommended approachand assuming that Absolution doesn’t completely change the series’narrative trajectory, it seems precisely what VanderMeer has done in the SouthernReach.

While I was researching The Conan Doyle Weirdbook (2012), likely in 2009 or2010, I came across a short guide to writing new weird fiction and scribbledsome notes in the inside cover of one of the key texts I keep on my writingdesk. In spite of many hours – probably one or two days even – of searching,I’ve never been able to find the guide again. (I assume it was part of anintroduction to an anthology, but I really should have found it by now.) Thereare three recommendations and I think they present a nice complement to Joshi’slist, albeit one focused on reinventing rather than transforming the genre. Based on my notes in the absence of the original, the recommendations are:

1. Extrapolating the internal logicof a speculative (or other) narrative.

2. Rewriting a particularnarrative in a different genre.

3. Deconstructing a speculative(or other) narrative.

The first might be said to have been used by Kiernan in her extrapolation of her fascination with the figure of the selkie in The Drowning Girl: AMemoir (2012). I have heard Miéville’s King Rat (1998) described asa retelling of the Pied Piper of Hamelin (c.1300), which is bothaccurate and an example of the second. I have already provided an example ofthe third in part III, with Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom(2016), although I suspect this method would be difficult to sustain tonovel length. (I am also fairly sure that the guide was for writing new weirdtales not new weird novels). Whatever form the future of weird fiction takes, Ilook forward to reading and watching more of it in TQF and beyond!

Recommended Reading

Fiction

Jeff VanderMeer, Annihilation, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2014).

M. John Harrison, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, Gollancz (2020).

China Miéville, The City & the City, Macmillan (2009).

Nonfiction

Jeff VanderMeer, Caitlín R. Kiernan on WeirdFiction, WeirdFiction Review (2012).

China Miéville, M.R. James and the QuantumVampire: Weird; Hauntological: Versus and/or and and/or or? Collapse IV (2008).

Robert Weinberg, The Weird Tales Story (2nd ed.), PulpHero Press (2021).

October 11, 2024

UNSPLATTERPUNK! 8 opens to fiction and art submissions!

Muck with a purpose: somewhat respected ezine challenges authors and artists to submit gore-saturated works with a positive message

Muck with a purpose: somewhat respected ezine challenges authors and artists to submit gore-saturated works with a positive message Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction, allegedly the UK’s second-longest running sci-fi/fantasy/horror ezine, has opened its portal for art and fiction submissions for the eighth chapter in the UNSPLATTERPUNK! series. The possibly talented but more likely self-deluded Douglas J. Ogurek will once again assume editorial duties.

Unsplatterpunk, horror’s most contradictory subgenre, pummels readers with all the grossness, violence and debauchery of splatterpunk while embedding a positive message. It’s kind of like putting a vitamin in a milkshake… a milkshake consisting of bodily expulsions and innards.

Send us your morally enlightening filth of up to 10,000 words by April 30, 2025. We’re also looking for cover art submissions that support the unsplatterpunk concept. Note: this is a nonpaying market, but all contributors (and everyone) will have access to free PDF and EPUB versions of the anthology as well as the option to purchase paper copies at the lowest possible price.

Forget the squeamish fans of mainstream horror, the instructors who told you not to write with a theme in mind, and even the splatterpunk writers mired in nihilism and gore for gore’s sake. We’re open to any genre, from vile fantasy and gruesome sci-fi to backwoods perversion and raw realism, provided that your tale exaggerates the ultraviolence and subversive content of the splatterpunk genre plus conveys a virtuous message. It’s all disgusting… and it’s all enlightening.

Dig into the first seven anthologies, all available for free:

UNSPLATTERPUNK! UNSPLATTERPUNK! 2 UNSPLATTERPUNK! 3 UNSPLATTERPUNK! 4 UNSPLATTERPUNK! 5 UNSPLATTERPUNK! 6 UNSPLATTERPUNK! 7 The UNSPLATTERPUNK! anthologies amplify the distasteful content of the typical splatterpunk story while adding a lesson in virtue. The message can be straightforward or subtle — we’ve even used allegories.

The UNSPLATTERPUNK! anthologies amplify the distasteful content of the typical splatterpunk story while adding a lesson in virtue. The message can be straightforward or subtle — we’ve even used allegories. Why Are Stories Rejected?

Following are common reasons why UNSPLATTERPUNK! submissions don’t pass muster:

Too tame. You’ve just written a story full of decapitations, amputations and eviscerations? We can get that by turning on the TV. How will you take it to the next level? We want something so disgusting and/or violent that it will knock the socks off the most desensitized reader.No positive message. You’ve completed a transgressive piece that will shock and disgust even the most dedicated splatterpunk enthusiast? Great. But if it doesn’t have some positive message – that’s where the UN in unsplatterpunk fits in – we’re not interested. Purple prose. When authors fall in love with their writing, they fixate on how they’re writing and lose focus on what they’re writing. We don’t care about what the sky is doing, how smoke drifts or what colour a character’s hair or eyes are… unless the descriptions contribute to the story. Don’t impress us with your language and vocabulary; impress us with your story.AI-generated stories. Don’t even try.Tips on Achieving the Almost Impossible

“Unsplatterpunk is an exceptionally demanding genre in which to write, requiring an almost impossible balancing act between the disgusting and the morally uplifting,” states author, criminologist, philosopher and aesthetic commentator Dr Rafe McGregor.

Having gone through this process seven times, we offer potential submitters the following tips:

Approach your subject matter with a thirteen-year-old boy’s “gross is great” mentality and your writing with the technical skills of a seasoned fiction writer.Make the story as attention-seizing as a T-rex at a butterfly garden. Develop content so revolting that readers think to themselves, Why am I reading this?Don’t forget humour. The over-the-top nature of these stories means there’s an element of humour in them. When authors take their subject matter too seriously, their work often devolves into dramatic hogwash.Imagine a man with a violin standing next to you as you write. Each time your writing gets dramatic, he starts playing. Don’t let him play! Fewer big words, abstractions and philosophical concepts – more story.Avoid standard revenge tales, which most often fail to deliver a positive message. It’s a cop-out, and it’s an overused concept in extreme horror.Don’t tack a moral lesson onto your conclusion; embed it into your story. This isn’t a cologne commercial or a performing arts student’s one-act play. Don’t end your story in a quagmire of esoteric nonsense.Our thoughts on classic creatures: Vampires brooding around a castle? Cliché. Zombies wandering deserted city streets? Dumb. Werewolves at a sexual harassment prevention training seminar? You have our attention.Read everything you can get your hands on, especially splatterpunk. You need a baseline from which to launch.Read previous entries in the UNSPLATTERPUNK! series. Why not? They’re free.Please, for the love of all that is holy, don’t write your story in a chatty style full of colloquialisms. You’re writing to your reader, not your bestie.The Gory Details

Send stories (no poetry, please) and artwork to TQFunsplatterpunk@gmail.com. Put “UNSPLATTERPUNK! 8 submission” in the subject line. In your cover letter, include a bio and tell us about the positive message your story conveys.

Deadline: 30 April 2025Max word count: 10,000Reprints: NoMultiple submissions: YesSimultaneous submissions: No. We’ll get back to you within a couple of weeks.File type: DOC (preferred) or DOCX files for stories; PDF or JPG files for artworkPayment: This is a nonpaying zine. However, free PDF and EPUB files will be available to everyone.After publication, you are free to reprint your story elsewhere, but please credit Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction for original publication. See the TQF standard guidelines for additional information on rights and legal matters.

A Note on No Payment

Because our contributors do not receive monetary payment, some have accused us of using authors’ “slave labour” to get rich. The UNSPLATTERPUNK! series (and the TQF ezine in general) is not a moneymaking venture. Rather, it’s a group of dedicated hobbyists trying to have some fun and maybe just make the world a better place. That’s why we make PDF and ebook versions of all UNSPLATTERPUNK! anthologies available for free (with an option to purchase a hard copy on Amazon). Over the course of the UNSPLATTERPUNK! series, we have collected next to nothing from hard copy sales, and all of this nothing has gone right back into the publication of the anthology.

Nevertheless, if writing is your job – or one day you want it to be your job – then of course you won’t want to do it for free. Submit your stories to a paying journal or anthology, or save them for your collection. And if you’ve been inspired to write something unsplatterpunkish, let us know so we can send readers your way! (And one thing we do offer contributors are free advertisements in the magazine for future projects relevant to our readers.)

Also, keep in mind that while some anthologists select contributors from a tiny pool of acquaintances, we take a different approach here. First, our sole criterion for acceptance is a good story that follows the parameters. Thus, everyone who submits has an equal chance of getting a story selected. Second, we read every submission from beginning to end. If we reject it, we tell you why. If we find promise in a story, we work closely with the contributor to make it as tight, violent, nauseating and illuminating as possible.

Earn the UNSPLATTERPUNK! badge. Submit stories and artwork by 30 April 2025.

Earn the UNSPLATTERPUNK! badge. Submit stories and artwork by 30 April 2025.Go Ahead: Yuck It Up

Readers who want to be disgusted and shocked by the content they consume continue to multiply. What appeals to them? Story, clarity, originality and above all, yuckiness.

Help us revolt against pointless splatterpunk by giving readers what they want and infusing the story with an uplifting takeaway. Join the growing ranks of the UNSPLATTERPUNK! army including such luminaries as Hugh Alsin, Antonella Coriander, Harris Coverley, Garvan Giltinan, Chisto Healy, Joe Koch, Eric Raglin, Triffooper Saxelbax and Drew Tapley.

What triggers your moral compass? Environmental destruction? Intolerance? Poverty? Inequality? Speciesism? Write us a story that shows us how to deal with it.

Now is the time to give splatterpunk readers a kick in the crotch. Make them cringe. Make them gag. Make them squeal. Dump all the barbarity, carnage and vileness you can into your milkshake, but don’t forget to mix in that virtue vitamin.

You have until 30 April 2025.

Shock us. Nauseate us. Edify us.

Pegging the President by Michael Moorcock (PS Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).Like other Jerry Cornelius stories, this brand new novella is a collage of in-jokes, allusions and references, and I doubt I caught more than one in ten of them. Your taste for that kind of thing will have a big effect on how much you enjoy the book. When I first read the Cornelius books, I found all of that funny because it seemed so random, cool and quirky. And even though I’m more used to the techniques being used, I still appreciate it. But I’m not going to pretend that I had a particularly good idea of what was going on in the story. What I did gather was that Jerry Cornelius, his friends, his family and his enemies, seemed to be slipping around in time, through different future and alternate history wars. All the favourites from the books show up: his sister Catherine Cornelius, Una Persson, Miss Brunner, Colonel Pyat, Shakey Mo, Jerry’s mum and dad, Cuban heels, Derry & Tom’s Famous Roof Garden. Even the famous needle gun makes an appearance. Jerry is still young, even though fifty years have (perhaps) passed, and he is able to do things like materialising in the seat of a car that someone else is driving. “The difference between fact and fiction”, Jerry comes to understand at one point, “[was] irretrievably blurred.” Each chapter begins with an extract: there are news items about the war in Syria, for example, and an extensive amount of It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, which has obvious relevance to present-day events in the USA: a capricious president who longs for the absolute power of a dictator, and a significant portion of the population also wishes he had it. It does break up the story a lot, though, and it feels as if you spend more time on the extracts than the adventure. It doesn’t help that a few of the extracts appear more than once, although that does reinforce the message. We thought we had set the ball rolling, thinks Jerry, but “all we’d done is start the pendulum”. Fans are likely to enjoy it very much, and I think it makes a pretty good entry point for those new to Jerry Cornelius – it’s no easier than the others, but it does give you a good idea of what they are like. Stephen Theaker ****

October 8, 2024

#OcTBRChallenge 2024: an A to Z of books and audiobooks

I always look forward to #OcTBRChallenge, where the idea is to clear as many books from your TBR list as possible in a month. I like to slice my collection a different way each year, and this time I'm reading as many of my short books as I can in A to Z order. The first one I finished was Ankle Snatcher by Grady Hendrix, about a family plagued by an actual monster under the bed.

I always look forward to #OcTBRChallenge, where the idea is to clear as many books from your TBR list as possible in a month. I like to slice my collection a different way each year, and this time I'm reading as many of my short books as I can in A to Z order. The first one I finished was Ankle Snatcher by Grady Hendrix, about a family plagued by an actual monster under the bed.B is for Bad Machinery, Vol. 10: The Case of the Severed Alliance, by John Allison. Her friendship with Shauna on the rocks, Lottie volunteers to work at a local newspaper. She discovers that the Chamber of Commerce is making blood sacrifices! Smashing, but sadly the last volume.

C is for Claudine à Paris by Colette, beautifully read by Isabelle Carré. Finished this, but have to admit I didn't follow it. I've been trying to improve my ear for French, and listening to this definitely helped, but I'm still picking out words and phrases rather than following the story. I listened to some of it with Android captions on, but it defeated the point since I just started reading instead of listening. If I listen to another French audiobook, I'll read a plot summary beforehand, so that I have some kind of framework to drop the bits I understand into, or maybe listen to a book I already know well.

D is for Doctor Who: UNIT Dominion by Nicholas Briggs and Jason Arnopp. As UNIT fends off more interdimensional incursions than the Evangelions, two Doctors turn up to help. One is a Scottish chap with an umbrella, the other is a haughty future Doctor, played by Alex McQueen…

E is for Earthdivers: Kill Columbus, volume 1 in a series written by horror author Stephen Graham Jones, art by Davide Gianfelice. In 2112, the native American survivors of an apocalypse try to fix things with time travel, by murdering Columbus before he reached their continent.

F is for Forager, a short graphic novel by Jimmy Palmiotti, Justin Gray and Steven Cummings. A couple on the rocks take their daughter on a spaceship to Mars, where she makes contact with something alien! Feels like a slightly more rushed version of ace Leo books like Betelgeuse or Aldebaran.

G is for Gallifrey: Weapon of Choice, an entertaining Big Finish Doctor Who spin-off by Alan Barnes, starring four of Tom Baker's companions: the second Romana, the first and second K9s, and the one and only Leela. In this story Romana, now President of Gallifrey, gives Leela a mission.

H is for How It Unfolds by James S.A. Corey, both of him: a short ebook with more ideas than most books ten times the size. It's about Roy, who takes part in an audacious colonisation project. Given how much I loved this, I should probably read the Expanse books.

I is for I'm Standing on a Million Lives, Vol. 1, a manga book by Naoki Yamakawa, with art by Akinari Nao, translated by Christine Dashiell. Stories of Japanese teenagers transported to an RPG game world are ten a penny, but its exploration of the game's mechanics is quite fun.

J is for Jeremiah Bourne in Time, a fun four-part Big Finish audio drama written by Nigel Planer. Jerry time-travels like Christopher Reeve in Somewhere in Time, by focusing on the details. His first accidental trip is to 1910, where he encounters various oddballs played by a splendid cast.

K is for Kounodori: Dr Stork, Vol. 1, by You Suzunoki, a genuinely moving manga book about a doctor who moonlights as an acclaimed and mysterious concert pianist. He cuts performances short when his patients go into labour. I got about 200 of these Kodansha books in a free giveaway.

L is for Lovers at the Museum by Isabel Allende, about a young couple found curled up asleep on the floor of a supposedly secure museum, first thing in the morning. I like how Amazon First Reads now includes some shorter ebooks – this fab fantasy story was a March 2024 selection.

M is for The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, by Christopher Hitchens, where he puts the reputation of this holiest of scammers under the microscope and takes a scalpel to it. Really is shocking to read of her heartless treatment of the sick and dying.

N is for Nameless by Grant Morrison and Chris Burnham, in which a psychic fights god, who turns out to be an otherdimensional alien imprisoned in an asteroid that's hurtling our way. The art is fantastic throughout, but it felt like the writer's magical beliefs rather swamped the story.

O is for One, Vol. 1: Just One Breath, by Sylvain Cordurie and Zivorad Radivojevic, also about a psychic, this time a "bloodcog" called on to investigate why the world is suddenly at peace. I read a lot of this book while the adverts were on during Rings of Power!

P is for Pay the Ghost by Tim Lebbon. A little girl goes missing and a year later her mum returns, sick and wasted away to nothing, ruined by a year of searching in supernatural territory, needing dad's help. I haven't seen the film, but it sounds like it left out some of the best stuff from the book.

Q is for Quarry's Cut by Max Allan Collins. When a former colleague kills a friend, the erstwhile hitman hunts him to an adult film shoot at a ski lodge. I adored Stefan Rudnicki's readings of other Quarry books, but Christopher Kipiniak's grimmer version here is great too.

R is for The River and the World Remade by E. Lily Yu. In a world of permanent flooding, some moved inland, others have floating homes woven from plastic bags and styrofoam; in this ace story a house-weaver battles a storm to save a young rascal from his own folly.

S is for Stone Ovaries and Bowling Balls Trapped in Beautiful Prodigy World, a title that left little room for much else in my tweet about it! An outrageous, hilarious unsplatterpunk tale by Douglas J. Ogurek, full of unhinged, profane wordplay, like Oscar Wilde writing for Rik Mayall. And it's hilariously read by J James – a handful of glitches can be forgiven on what must have been a very challenging production. I'm biased, obviously – Douglas has probably contributed to more TQF issues than me at this point! – but I was laughing out loud throughout.

T is for Taproot, collecting and expanding a webcomic by Keezy Young. A gay ghost has a crush on a bisexual gardener, whose efforts to keep his plants alive unwittingly cross the line into necromancy! The odd pacing reflects its webcomic origins, but it's sweet and the art is lovely.

U is for Undercover by Tamsyn Muir, a twisty-turny urban fantasy story about a tough woman hired to bodyguard a gangster's ghoul, read by Susan Dalian. One of those nice books where if you borrow the ebook in Prime Reading, you can claim the audiobook to keep for good in Audible.

V is for Vampire Dormitory, Vol. 1, by Ema Tōyama, a gay vampire romance manga book very much aimed at female readers, to the point that one of the boys is secretly female and binding her breasts. Has the cute idea that vampires seduce humans because love makes our blood sweeter.

W is for Walking to Aldebaran, the audiobook jauntily read by the author, Adrian Tchaikovsky. British astronaut Gary Rendell is lost in the Crypts, a mysterious interplanetary nexus where various aliens try to survive among the detritus of each other's failed expeditions, and time gets weird.

X is for XIII Mystery, Vol. 6: Billy Stockton, by S. Cuzor and L.F. Bollee, the life story of a supporting character from volume 3 of the main XIII series. It's misery on top of misery as a child who loses his parents in a plane crash grows up to inflict misery on others in turn.

Y is for The Year of Magical Thinking, the audiobook version of a one-woman play by Joan Didion, based on her memoir of the year that followed her husband's death, and led up to her daughter's death, performed by Vanessa Redgrave. I gave the littler Theakers a big hug after this.

Z is for Zodiac Starforce, Vol. 2: Cries of the Fire Prince, written by Kevin Panetta, art by Paulina Ganucheau. A defeated enemy is so desperate for revenge on Zodiac Starforce that she tries to summon a demon goddess, but gets instead the goddess's pet dancer.

A to Z complete!

October 4, 2024

Too Like the Lightning by Ada Palmer (Head of Zeus) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in Interzone #272 (September–October 2017).

This review originally appeared in Interzone #272 (September–October 2017).It is the year 2454, and the Seven-Ten lists are about to be published. Produced by the most significant newspaper of each hive, these lists rank the ten most important people in the world. But the list of the Black Sakura has been stolen and taken to the Saneer-Weeksbooth bash’house, apparently with the help of the so-called Canner device, which conceals a traveller's identity. Whoever did this seems to have several purposes in mind, and knows exactly what secrets they want brought into the light.

A series of innovations have set this world apart from ours, each of them fully explored and integral to the plot. The earliest seems to have been the institution of the Bash' – extended family groupings of friends and like-minded individuals to encourage intellectual development. One result of this was the development of high speed mass transit at the Saneer-Weeksbooth Bash'. One might wake up in one country, go to work in another, and attend a party in a third, all of it loosening the bonds of nationalism. Lifespans have been extended, and ageing prevented.Then came the Church Wars, which in causing disaster led to the foundation of the hives. European citizens had long been able to claim floating citizenship, and at the point of crisis it was offered to everyone in the world, and other transnational groups followed suit. Young people can choose which hive to join: Masons, Humanists, Mitsubishi (incorporating Greenpeace), Europe, Cousins, Gordians or the Utopians, the forward-thinking geniuses undertaking the colonisation of Mars. But people can still switch, hence the importance of the Seven-Ten list.

Our narrator Mycroft Canner is hiveless. He is a servicer, one of those at the bottom of the social order, former criminals who now work for food. He was caught back in 2440, and has since become a reliable, hard-working and useful member of society. He owns just five possessions: a tablet, a photograph of his birth-bash’, a copy of the Iliad, and a bookmark. As events proceed, the book reveals, with the skill of a magician, ever more of our protagonist (though Canner argues that another should bear that title) and his extensive connections in the world.

Another major character is Carlyle Foster, a sensayer. Organised religion has been forbidden since the Church Wars, and so those who need to discuss spiritual matters are assigned a sensayer, expert in all religions and beliefs. The sensayer of the Saneer-Weeksbooth bash'house having died, Carlyle is sent to replace them, and upon their arrival is immediately embroiled in everything that is going on, in particular a boy, Bridger, who can bring toys and drawings to life, as evidenced by the tiny soldier Carlyle sees dying on the kitchen table, reverting to green plastic once his blood runs out.

Like religion, gender is a hot button issue in this world. They is used for everyone rather than he or she, and clothing is carefully neutral, and thus hints of gender become as powerfully erotic as Victorian ankles. Mycroft genders and misgenders people according to stereotypes; the reader may assume they don't know the gender of anyone he describes. One wonders how translators of this book into highly gendered languages such as French will approach it: perhaps Mycroft will gender his nouns, while others will not.

Though it is very good, this isn't a book that would be particularly satisfying to read on its own – it is absolutely the first half of a long novel that has arbitrarily been split in two. It does build up to a significant revelation, but no storylines resolve. However, the second volume Seven Surrenders was published in the UK on the same day as this one, and a preview is included – two chapters in the print edition (which, incidentally, has notably small text), and three in the ebook – so there's no delay for readers keen to begin the second half.

Taken as the first half of a novel, this is fascinating and perfectly paced: Mycroft parcels out secrets and opens his world to us in a way that makes the relative lack of action unimportant. It's mainly reaction, revelation, set-up and mystery, but readers won't mind that in such a well-built world full of rich and vibrant characters, like the heroic toy soldier Major, or the alarmingly perceptive J.E.D.D. Mason. Eventually there is a big shift in the book, and some readers may find it harder to read from that point. While I wouldn't blame anyone for stopping, I think it rewards those who persist. Stephen Theaker ***

September 30, 2024

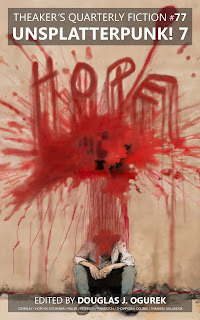

Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #77: Unsplatterpunk! 7 is now out in paperback and ebook!

free epub | free pdf | print UK | print USA | Kindle UK | Kindle US

free epub | free pdf | print UK | print USA | Kindle UK | Kindle USWelcome to Theaker's Quarterly Fiction #77: Unsplatterpunk! 7, edited by Douglas J. Ogurek.

The Good News According to GoreGet ready to gag, cringe and squirm. Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction erupts with yet another geyser of violence and grossness in this seventh instalment in the UNSPLATTERPUNK! smearies. These six tales, covering everything from a nightclub basement’s revolting contents to bone-crushing brawls atop a mesa, inject a positive message into the characteristic splatterpunk barbarity and filth.

A girl with aspirations of escaping her farming town gives a dilapidated scarecrow a makeover. Alternative music brings comfort to a young woman undergoing cruel experiments. The meaning of a phrase inspired by a nineteenth century event mutates from enigmatic to vile to hopeful. In a disgusting retelling of the mice falling into cream parable, two men find themselves stuck in fluid. Hint: it’s not milk. An ancient stranger unleashes debauchery among the self-absorbed patrons at an upscale bar. Kung Fu Sue returns from her last adventure to break, chop, snap and tear her way through the most unsavoury adversaries.

The stories that follow deliver a heaping portion of broken spines, bashed in skulls and severed flesh steeped in a revolting soup of bodily expulsions. When you emerge from it… if you emerge from it… expect to feel besmirched and enlightened.

The cover art is by Edward Villanova. In the Quarterly Review, Douglas Ogurek and Stephen Theaker look at Bludgeon Tools: Splatterpunk Anthology, edited by K. Trap Jones, Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas, 47 by Walter Mosley, Hell to Pay by Matthew Hughes, The Night Parade by Ronald Malfi, Positive by David Wellington, Stitches by Hirokatsu Kihara and Junji Ito, and Stray Pilot by Douglas Thompson, plus, in the film and television sections, Boy Kills World, Civil War, Geethanjali Malli Vachindi, Halloween Ends, IF, Immaculate and Twisted Metal, Series 1.

Here are the virtuous contributors to this issue.

Brett Petersen is the author of The Parasite From Proto Space & Other Stories, drummer for alt-rock group The Dionysus Effect and copyeditor for CLASH Books. He is also a competent visual artist and tarot reader and is proudly autistic. He enjoys Japanese role-playing video games such as Xenoblade and the Trails series, and he lives just outside of Albany, New York. Everything he does can be found at linktr.ee/brettpetersen.

Bryan Miller is a writer and performer based out of Minnesota. His fiction has appeared in The Drabblecast, The Bombay Literary Magazine, Shadowy Natures: Stories of Psychological Horror, The Monsters We Forgot Part 1, and more than a dozen other journals and anthologies. His work has been featured on The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, SiriusXM, the comedy special Panic Room, and two comedy albums: 2020 and All the New Ugly People.

Douglas J. Ogurek is the pseudonymous and sophomoric founder of the unsplatterpunk subgenre, which uses splatterpunk conventions (transgressive/gory/gross/violent subject matter) to deliver a positive message. His short story collection I Will Change the World One Intestine at a Time (Plumfukt Press), a juvenile stew of horror and bizarro, aims to make readers lose their lunch while learning a lesson. Ogurek also guest-edits the wildly unpopular UNSPLATTERPUNK! “smearies”, published by Theaker’s Quarterly Fiction. These anthologies are unavailable at your library and despised by your mother. Ogurek reviews films and fiction for that same magazine.

Edward Villanova is a horror author, podcaster and content creator who dabbles in horror-themed visual art, and provides the cover art for this issue. He is inspired by the works of Zdzisław Beksiński and Junji Ito, preferring to focus on the implications of a scene depicted more so than the subject of the artwork. He currently resides in Dallas, Texas and is an active member of the Sicilian community there.

Harris Coverley, a returning UNSPLATTERPUNK! contributor, has had more than a hundred short stories appear in publications such as Penumbra, Hypnos, JOURN-E and The Black Beacon Book of Horror (Black Beacon Books). He has also had over two hundred poems published in journals around the world. He lives in Manchester, England.

Pip Pinkerton was born and raised in Oakdale, Minnesota. Pip is a wanderer and a dreamer. He loves writing short stories, poetry and screenplays. A former theatre student and current guitar player, Pip co-manages a record shop. When he is not writing or jamming, he is spending time with his trusty rottweiler, Shrimp. Pip’s work appears in Monstrous Femme, and he has a story forthcoming on HorrorAddicts.net.

v.f. thompson is just compost in training. She can be found clowning around Kalamazoo, Michigan. She is the editor of Trans Rites: An Anthology of Genderfucked Horror, and her work may also be found in Monster Lairs from Dark Matter Ink, The Crawling Moon from Neon Hemlock Press, The Hard Times, and a smattering of other publications. Her play, Taproot, is set to be performed as part of Queer Theatre Kalamazoo’s upcoming 2024–25 season.

While Dafydd Rhys Hopcyn-Kitchener’s day job is in accountancy, writing is his real passion. He is a fan of short, sharp page-turners, and he writes to entertain. Check out his Westerns (published by The Crowood Press), his romantic novel Stranger from the Sea (published by DC Thomson) and his self-published horrors.

As ever, all back issues of Theaker's Quarterly Fiction are available for free download.