Stephen Theaker's Blog, page 5

April 21, 2025

Rediscovered! Lost tales by Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker | review by Rafe McGregor

, Newell & Newell, paperback (saddlestitch binding), £13.99, 6 April 2025

Newell& Newell is a small press run by husband and wife Adam and Sharon Newell inPenrith in Cumbria. The press is located in their secondhand bookshop, WithnailBooks, which I found via The Book Guide, awebsite I cannot recommend highly enough for anyone who still enjoys theexperiences of travel, old-fashioned browsing, and being able to hold books inyour hands before you buy them. As far as I can tell (because I’ve not had theopportunity to visit yet), Newell & Newell publishes limited editions of 250chapbooks every few months, which can only be ordered via the Withnail Bookswebsite and which sell out very quickly. Rediscovered! is my secondpurchase, following The CroglinVampire: England’s Earliest Vampire Legend? in November last year. I think The Croglin Vampire soldout before its publication, but at the time of writing there are still a fewdozen copies of Rediscovered! available. Rediscovered! is a pair ofchapbooks from two of the three (or four, depending on whom one asks) mastersof Gothic fiction in general and Victorian horror more specifically: MaryShelley, author of Frankenstein;or, The Modern Prometheus (1818),and Bram Stoker, author of Dracula (1897). Along with Robert Louis Stevenson’sThe Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), these two novels complete thetrilogy of quintessential Gothic horror, with either Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) or Robert W. Chambers’ The King in Yellow (1895) sometimes expanding the trilogy to aquartet.

With sucha pedigree, there is bound to be a great deal of interest in anything andeverything Shelley and Stoker wrote and Stoker’s short stories, several ofwhich I reviewed way back in TQF24, have aged surprisingly well. Stoker published about 50 in total and ‘GibbettHill’ is not available anywhere else either in print or online. It was publishedin the Dublin edition of the Daily Express on 17 December 1890 and is 11pages long in its chapbook form, accompanied by a print of J.M.W. Turner’s ‘HindHead Hill’ (1811), the etching that inspired the story. ‘Gibbett Hill’ describesthe unnamed narrator’s three encounters with a trio of sinister children on theroad between London and Portsmouth and is a beautifully written weird tale,albeit not one of Stoker’s best. My main interest was the extent to which it anticipatesThe Lair of the White Worm (1911), which I regard as his unfinishedmasterpiece and has fascinated me for many years. ‘Gibbett Hill’ shares severalof the flaws of the novel, including Orientalism and a lack of internal logic,but is nonetheless well worth reading.

Shelley published about half as many shortstories as Stoker, most of which appeared in The Keepsake, The LondonMagazine, and The Liberal. ‘The Ghost of the Private Theatricals: ATrue Story’ was published in The Keepsake at the end of 1843 and remainedunavailable to the public until it was released by Newell & Newell in alimited edition of 100 in 2019. The chapbook, which includes the 23-page shortstory and an afterword by Adam Newell, is accompanied by a print of ‘Heidelberg’(1845), an engraving after Turner that may have been Shelley’s source ofinspiration. ‘The Ghost of the Private Theatricals’ is narrated by the aristocraticIda Edelstein and set in Schloss Trübenstern, a fictional castle inGermany. Ida travels to the castle with her brother to attend the wedding ofher sister and the story evinces all the typical and much-loved Gothic Romanticpreoccupations with tortured family relationships, brooding ancestral homes,and unexplained deaths. The private theatrical of the title is an unnamed playthat the characters agree to stage, a ghostly tale within a ghostly tale whichserves as the engine of what is ultimately a delightful and suspenseful exemplarof its genre.

April 14, 2025

Octavia Butler's Parable of the Trickster

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower wasintended to be part of a series of six novels, which was planned as Parableof the Talents, Parable of the Trickster, Parable of the Teacher,Parable of Chaos, and Parable of Clay, but only the first twowere ever published, in 1993 and 1998 respectively. The first three Parablestake their titles from the three biblical parables of the same names, inthe Books of Luke and Matthew, and each of the published novels concludes witha quote from the relevant Book. In The Parable of the Sower, the sower issymbolic of God and the seed of God’s message. Lauren Oya Olamina, theprotagonist of the first two Parables, creates a new religion calledEarthseed and founds the first Earthseed community in Humboldt County,California. Following the discovery of extrasolar planets that sustain life in2025, the ultimate aim of Earthseed is to ‘take root among the stars’. The Parablesare referred to as Butler’s Earthseed books in order to distinguish themfrom her other two series and her standalone novels. In The Parable of theTalents, the monetary talents (a unit of weight used as currency) are symbolicof personal talents (God-given abilities and aptitudes), both of which aregranted for the purpose of serving their respective masters. Olamina dedicatesher life to the service of Earthseed, which becomes one of the most popularreligions in the Americas, and launches the first starship in 2090, the finalyear of her life. In The Parable of the Trickster, which is better known as TheParable of the Dishonest Steward (or the Shrewd Manager), the steward’salternating incompetence and prowess is symbolic of the inability of humanbeings to serve both God and money. The Earthseed settlers on the planet Bow (anabbreviation of 'Rainbow') cannot both cling to the form of life they had onEarth and thrive in the extrasolar colony.

Butler began work on Parable of the Trickster in1989, made numerous false starts from 1999 to 2004, and continued compiling notesand drafts until her death, early in 2006. The premises, outlines, andfragments have been available in The Huntington’s Octavia E. Butler Papers archivesince 2013 and I was lucky enough to gain access to these while researching Literary Theory and Criminology in 2022. There are several aspects of Butler’s premises,outlines, and fragments that remain fairly consistent, most of which concernthe protagonist and setting of the novel. There is less consistently about thestructure of the narrative, but two plotlines can be discerned as well as athird that is only sketched. Butler seemed certain that Trickster would be written in the first person from the perspective of theprotagonist and narrator, who would be named either Imara Hope Lucas, ImaraWright Drew, or Imara Dove Holly. Imara is an African American woman who wasadopted by Olamina during her teens (between 13 and 17) and is aged between 35and 45 when the story begins. Imara is an Earthseed therapist in some versionsand a sharer (suffering from the organic delusional disorder calledhyper-empathy, like Olamina) in others. Some time between 2090 and 2095 sheleaves Earth in an Earthseed Instar with between 4700 and 5339 colonists torealise the Earthseed destiny. Given the dates this appears to be the starshipfleet led by the Christopher Columbus described at the end of Talents.

After a flight of between 107 and 137 years,during which Imara is placed in DiaPause, a method of suspended animation, shearrives on Bow, which is 11.8 light years away from Earth. Bow can supporthuman life, with plenty of oxygen and water. The planet has no moon, is coolerthan Earth, and has days that are just under 20 hours long. The ships havearrived near the equator, where it is warm, wet, and windy and the plan is tobuild the colony in a river valley. In most versions, Bow has no fauna beyondearthworms and microorganisms and flora that is limited to a slimy moss-likesubstance. The settlers immediately miss the beauty of Earth, a feeling that isexacerbated by the fact that the colours on Bow are all muted and theatmosphere smelly, varying from being merely unpleasant to smelling like vomit. Two of the three plotlines begin five years after thearrival of the humans, by which time there is a fully functioning settlementand society. The colony is divided into 50 to 60 housing groups of 30 to 100people each, built in a protective semicircle around their crops and watersupply. Each housing group has a communal gathering house at its centre, butthe individual houses are inhabited by nuclear families. The aim is to developthe colony by having a new housing group split off from the parental house oncea group reaches 100 inhabitants. The minimal governmental functions, includingleadership by an Earthseed shaper (clergyperson) and record-keeping by anarchivist, are based in a gathering hall, which serves as the community centre.The colony is multinational and multi-ethnic, with each of the colonists beingselected for their skill set. By the fifth year, the colony is fullyestablished, with the colonists living off the land. At some time in thefuture, after Trickster, it will break up, with some housing groupschoosing to merge into a town, others developing around industrialised farms,and others adopting pre-industrial gatherer or monastic lifestyles. Once onemoves beyond the protagonist and the setting, there is little consistency inthe Trickster archive. Three plotlines nonetheless emerge from the notesand fragments, two of which are fairly substantial.I shall consolidate the notes and fragments to produce an account thatsacrifices accuracy for coherence.

In the first, which includes a fragment of 47pages, Imara Lucas Hope is the expedition’s archivist. She was raped by hermother’s partner at the age of 13, became pregnant with his child, wasabandoned by the couple, and tried to commit suicide in an orphanage. Theunborn baby died, but she survived to be adopted by Olamina. Imara and Olaminabecame very close as the years progressed and she was appointed ‘Guardian of theAshes of Lauren Oya Olamina’, which are to be scattered on Bow in an Earthseedfuneral on Day 2000 of the arrival of humanity. The narrative begins on thatday, in medias res as the community leader, shaper Eric Parnell, appearsto lose his mind when he starts shouting nonsense in his opening speech. Imara,waiting to play her part in the ceremony, has a hallucination of the thousandsof colonists in the hall panicking, stampeding, and injuring oneanother in a race to exit. Eric is taken to the clinic and Imara realises thathe, she, and the community’s dentist, Luis Huerta, have all had hallucinations.They all seek physical explanations, but none can be found and they haveconcerns about their sanity, worrying that they may not be able to cope withprolonged exposure to the conditions on Bow (which can support them physically,but perhaps not psychologically). Claire Lawless, Eric’s deputy, and MuirParnell, Eric’s wife, have also been hallucinating and there is some tensionbetween Claire and Imara. In the following chapter, Imara wakes up the nextmorning feeling fine, but immediately hallucinates a conversation with Olamina.Seven more people are admitted to the clinic with hallucinations during the dayand Imara realises that the community’s psychiatrist, Ross Kuusi, is trying toconceal the fact that he is also hallucinating. Concerns about prolongedexposure to the planet are exacerbated when Imara works out that everyone whohas been hallucinating is either part of the last transit crew or the firstground crew, the only people who were awake in the first 100 days of arrival.

In the second plotline, which has more dedicatedfragments but of shorter lengths than the first, Imara Wright Drew is theexpedition’s psychiatrist. The narrative opens with her awakening from her‘coffin-sized DiaPause tank’ and gradually recovering her senses and motor control.Imara is part of the first ground crew and the reports from those who haveexplored Bow are negative: while it can clearly sustain human life everyone hasfound being on it either disconcerting, unpleasant, or both. Imara finds outthat after she was put in her DiaPause tank, her husband, Powell Davidson,changed his mind and decided not to join the Earthseed expedition. She is givena letter from him apologising for his decision and realises that he is now longdead. In the following chapter, Imara begins to regain her strength and othercolonists are introduced: Aaron Wen, a shaper; Nissa Swan, an anthropologist;Julian Gamero, a farmer; and others. Imara begins helping other people wakefrom DiaPause. Three days later, Nissa goes missing. She had previouslyexplored Bow and claimed to have seen an indigenous species. A search party issent out for her. They find her trail, track her, and quickly locate her corpseat the bottom of a canyon. Imara is asked to attend the scene. As soon as shegoes outside she has an hallucination and it will subsequently be suggestedthat the hallucinations were responsible for both Nissa’s sighting of anindigenous species and her death by falling. Imara starts thinking aboutadapting to rather than curing the hallucinations, at least in the short term,and this is both the resolution to the plot and the core theme of thenarrative.

In the third plotline, which is sketched in thebarest detail, Imara Dove Holly is the expedition’s law enforcement agent, theSheriff of Bow, selected personally by Olamina before the expedition departed.Imara is married to a farmer, Aurio Cruz. When she does not have law enforcementduties to fulfil, she assists both her husband and the colony’s archivist. Fiveyears after the colonist’s arrival someone sets a fire outside the largestgreenhouse of the Rose Housing Group, causing considerable damage. When Imarabegins her investigation, she has her first hallucination and subsequentlylearns that many people are hallucinating frequently. There is a second fire,in consequence of which one of the colonists is killed. The ubiquity of thehallucinations make the case almost impossible to solve, but Imara eventuallyfinds a way to make use of the hallucinations to detect the arsonist while themedical professions continue to seek a cure. Strangely, given the amount ofrelative detail provided, there is no suggestion of a central theme in thearchivist’s plot. The strongest suggestion is in the psychiatrist plot, inwhich the solution to the problem of the hallucinations is not to ‘cure’ orovercome them, but to accept them as one of the features of life on Bow inorder to minimise their impact on everyday life. The sheriff’s plot goes even further, suggesting that the hallucinations are not just a phenomenon that human beings can live with, but a phenomenon that can actually be exploited for gains of some sort. There is an allusion to this idea in the archivist’s plot, in which the narrator reflects that ‘two of the most important tenets of Earthseed were foresight and adaptability’ before Parnell addresses the community about their adaptation to life on Bow. In the context of the other plotlines and extracts, the double emphasis on adaptation immediately prior to Parnell’s very public hallucination may well be an instance of foreshadowing the resolution to come: adaptation rather than cure.

The theme of adaptation is developed in Butler’snotes by means of two concepts or metaphors, the xenograft and the trickster. Axenograft is an interspecies transplant and she described the story as one inwhich people xenograft humanity onto a new world whose immune system tries toexpel them. The resistance of Bow to humanity is the sense in which the planetitself is the trickster of the title and parable and the hallucinationssuffered by those with prolonged exposure to the planet are the most dangerousmeans by which it tries to expel them. Butler was explicit as to the planet’strickery, ‘a world that seems to be one thing (dull, drab, and harmless) and issomething else entirely.’ Her planned conclusion to the novel was that thecolonists would be forced to make a choice, ‘to try to hold on to what theywere as normal human beings on Earth or to allow the change they have bothfought and adapted to for years to continue.’ She also wrote that in the endBow ‘will adopt them and they will be of it.’ As a sequel to both Sower andTalents, this theme is completely consistent consistent with the Earthseed principle of ‘God is change’ and Olamina’s insistence on employing it as a guide to one’s life. To return to the biblical parable, thehuman beings on Bow cannot retain their human form of life on Bow, but mustdevelop and establish a new form of life that is adapted to the planet on whichthey have chosen to live. This also provides a neat juxtaposition to the darknote at the end of Talents, in which the starship is revealed to havebeen named the Christopher Columbus, predicting that the form of life inthe extraterrestrial colony will be as unjust and unsustainable as it was interrestrial colonies. As such, it seems as if Trickster was intended toproceed through conflict and tragedy to a conclusion with life-affirming meaning.As Butler writes: ‘The community will suffer greatly at the hands of thehallucinations, but eventually pull through.’

Butler had little more than premises for the secondhalf of the series. The colony would divide into two in Parable of the Teacher,with one group determined to adapt to the planet and the other determined toconquer it. Parable of Chaos would see the rise of ‘an absoluteStalinesque figure’ whose every word and whim is passed into law by hissycophantic followers. Finally, in Parable of Clay, humanitywould not only have adapted to life on the new planet, but actually evolvedinto a new species or subspecies. The themes the four novels set on Bow wouldexplore would be the roles of creativity and repression in adaptation to theenvironment and new ways of being human that revealed marginalised aspects ofhumanity. Butler suffered from high blood pressure in her final years and diedfollowing a fall while walking in Lake Forest Park, in Seattle, at the age of 58. She became the first Black woman to be a published science fictionwriter when Doubleday released her first novel, Patternmaster, in 1976. Alongwith Samuel R. Delany, she is recognised as inaugurating Afrofuturism asa literary movement. As far as the continued relevance of her work, Butler’sEarthseed novels are only matched by Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006feature film, Children of Men, and the eight seasons of HBO’s Game ofThrones, released from 2011 to 2019.

April 7, 2025

The Last Days of New Paris | review by Rafe McGregor

by China Miéville, Picador, paperback, £9.00,23 February 2017, ISBN 9781447296553

China Miéville has been publishing speculativefiction for the better part of three decades, beginning with King Rat in 1998. In the course of thiscareer, he has become known as the foremost exponent of the New Weird, rivalledonly by Jeff VanderMeer, and last year he published The Book of Elsewhere,co-authored with none other than Keanu Reeves. I defined the New Weird as philosophicalin virtue of presenting or representing a fully-fledged and fleshed-outworldview, generically hybrid in character, and foregrounding the alienationwithin ourselves in Weird Fiction, Old, New, and In-Between, also publishedlast year. It is difficult to avoid appreciating The Last Days of New Paris in one of two misleading contexts. The first is as an Axis victory alternative history along the lines of Philip K. Dick’s 1962 The Man in the High Castle or Len Deighton’s 1978 SS-GB, both of which have been released as popular television series, the former in 2015 and the latter in 2017. Miéville weaves two narratives together – one set in a recognisable France of 1941 and the other in an unrecognisable Paris of 1950 – and populates each with a mix of real and fictional people, but doesnot invite one to ruminate on the possible consequences of, for example,Franklin Roosevelt’s assassination (Dick) or a Luftwaffe victory in the Battle of Britain (Deighton). Instead, thegeopolitics that led up to and followed on from the ‘S-Blast’ (presumably‘surrealist blast’), the explosion that both created living manifestations ofsurrealist works of art and opened the gates of hell, are for the most partcircumstantial. The second context, which may be related to the first, is tosee the novella as a response to the global rise of nationalism, often inextreme forms, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, but it isneither a call for political resistance nor a naïve allegory of art’s revolutionarypower.

The Last Days of New Paris consists of ninechapters, with the odd numbers devoted to events in the 1950 present and theeven numbers to events in the 1941 past. The story is followed by an afterwordand a notes section and my only criticism concerns the inclusion of thissupplementary material. The afterword is subtitled ‘On Coming to Write The LastDays of New Paris’ and constitutes a curious conceit in which Miéville claimsto have met Thibaut, the fictional protagonist of 1950, and to have merelyedited the manuscript passed to him. This was a common device in Victorianfiction, but contemporary readers require no such faux guarantees and thesuperfluity is exacerbated by Miéville’s reference to non-existent sketches hehas (not) included. The notes are explanations of the artworks referred to in the narrativeand feel gratuitous in an age where reader research is almost effortless. Miéville’stextual representations of these works are a seamless merging of the realistic withthe oneiric and his expert evocation of the pervasive sense of the strange thatis New Paris equips the reader with all he or she requires to experience theintense pleasure afforded by the novella.

New Paris is Paris after the S-Blast, whichoccurred in 1941. In Miéville’s alternative Europe, Fall Gelb (Case Yellow) – the German drive to the Channel in May1940 – was sufficient to cause the collapse of France, making Fall Rot (Case Red, the push west andsouth the following month) unnecessary. The S-Blast transformed Paris from acity of occupation to a city of resistance, with various French factions risingup against the Germans and the ‘battalions from below’ rising up to join thechaos. The resistance includes the Free French, led by Charles de Gaulle andbacked by the United States, and the Mainà plume, the surrealist irregulars, some of whom (like Thibaut) have beenable to harness the power released by the detonation. The most significant effectof the S-Blast was not the release of hell’s minions (who show only a passinginterest in the city), but to create the living manifestations of surrealist artworks,‘manifs’, that roam the streets either on their own or under the less thanperfect command of surrealist or SS handlers. By 1950 the Germans have sealedthe ‘city become free-fire zone andhunting grounds for the impossible’ and are attempting to destroy the resistersby all available means, including the control of manifs and devils and thecreation of manifs of their own, using the work of Nazi artists likeArno Breker. The S-Blast has of course given literal meaning to metaphors suchas art coming to life, having a life of its own, and being a form of life.

The Last Days of New Paris is an extraordinarily original work that underscoresMiéville’s considerable ingenuity and innovation. The opening scene is wildly fantastic,a suicidal charge by the Vélo – the manifestation of LeonoraCarrington’s I am an Amateur of Velocipedes (1941), a bicycle-woman centaur – at the German lines.There is also a satisfyingly overdetermined symmetry in the work’s design asthe onset is bookended by the appearance of Fall Rot, a Panzer III-giantman centaur, in the first stage of the story’s tripartite climax. The symmetryis superbly complex: in the same way that science and the supernatural are thedual interests of Jack Parsons, the real-life protagonist of the 1941narrative, so Fall Rot has been created by the combination of the biologicalexperimentation of Josef Mengele and the perverted faith of Robert Alesch, a Catholicpriest who collaborated with the Nazis. In a further parallel, both of theplots begin with the arrival of an American on the scene, Parsons in VichyMarseilles in 1941 and an American photojournalist named Sam in the free partof Paris in 1950. Sam is researching her own book, The Last Days of NewParis, a photographic essay-within-a-novella that pays homage to Dick’s TheGrasshopper Lies Heavy novel-within-a-novel.

Miévilleis too sophisticated a writer to promote a conception of art as essentiallyopposed to oppression and his mention of Breker and the second part of theclimax (which I shall not reveal) shows that he is well aware of the variety ofends art can serve. While Breton’s surrealism provided a Marxist opposition to Europeanfascism and American Fordism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s futurism provided activeand enthusiastic support for Mussolini and the fascist sympathies of manyprominent modernists are well documented. Miéville is concerned with surrealismin particular over and above art more generally because movements like surrealism(and now New Weird) resist nationalism and elitism in virtue of beingpolitico-artistic movements in the first instance. Surrealism is not anartistic movement in the service of Marxism, but a Marxist artistic movement. Assuch, The Last Days of New Paris calls for a revolt in art rather than arevolt in politics, for integrating politics into art rather than employing artas a means to political ends. The link from New Paris to the contemporary worldcomes in the perfectly pitched anti-climax with which the narrative concludes,as Thibaut takes it upon himself to write his own book, to start ‘from scratch,redo history, make it mine.’ In Thibaut’s return to the fray to write hisrevolution, Miéville urges readers to their own artistic revolt, to the reconception of artas essentially rather than circumstantially political and the New Weird asessentially rather than circumstantially resistant to nationalism, elitism, andrelated mass harms.

April 6, 2025

Apologies and scheduling: TQF in 2025

A quick note to apologise to everyone who has sent in submissions for issues 78 to 81 and is waiting for me to do my bit. The magazine isn't dead, don't worry, work is progressing, albeit slowly, on them all, but my daytime work has been keeping me busy in the evenings too, so I've been struggling to finish things off.

A quick note to apologise to everyone who has sent in submissions for issues 78 to 81 and is waiting for me to do my bit. The magazine isn't dead, don't worry, work is progressing, albeit slowly, on them all, but my daytime work has been keeping me busy in the evenings too, so I've been struggling to finish things off.I'm past the worst of that now, though, and I'll be cracking on with all the outstanding work needed on TQF. Most of the next three issues are already typeset and waiting to be proofread, while my co-editor John and my co-habitee Mrs Theaker have been assiduously reading new submissions, and Douglas Ogurek has been hard at work at the next Unsplatterpunk! special.

It seems sensible to close submissions for regular issues until October, since there's no point adding more to the queue just yet. But submissions to Unsplatterpunk! 8 are open till the end of April.

So, my plan for the year is now to put out an issue of TQF monthly until I am all caught up, working through the issues already in hand, and slotting Unsplatterpunk! 8 in when it's ready.

My apologies again to everyone. Each time I said I was hoping to have the next issue ready at the weekend or by the end of the month, I genuinely did mean it, but I ended up having to put other things first. Don't get me wrong, I've been loving my work this year, but by the end of the day I was too worn out to do much more than read manga and play a bit of Monster Train. I haven't finished a single novel yet this year!

Finally, I have to express my gratitude to Douglas Ogurek and Rafe McGregor, who have kept the lights on here with reviews and articles while I've been slacking off.March 31, 2025

Midnight, Water City | review by Rafe McGregor

byChris McKinney, Soho Press, paperback, £13.79, 15 July 2021, ISBN 9781641293686

Chris McKinney’s career as an author began with TheTattoo in 2000 and Midnight, Water City is his seventh novel. Thescience fiction mystery is his first work of genre fiction, the first not setin his home state of Hawaii, and the first instalment of the Water CityTrilogy, which continues with Eventide, Water City and concludeswith Sunset, Water City, both published in 2023. Midnight, Water Cityis narrated in the first person by an anonymous narrator and in the presenttense. It took me some time to realise both, which is a mark of the author’s literaryskill. While use of the present tense can make for a more immediate, engrossingreading experience, it is difficult to do well and can have the opposite effectwhen it fails, undermining the suspension of disbelief. The narrative opens in2142, with the murder of Akira Kimura, forty years after she saved the planet froman extinction event. Kimura was initially despised for being the bearer of badnews when she identified Sessho-seki (Japanese for ‘The Killing Rock’),the asteroid on a collision course with Earth, and then because of her undisguisedmisanthropy when interviewed about it. Although she thought that only a tinyproportion of humanity was worth saving, she turned her genius to the creationof Ascalon, a cosmic ray powerful enough to alter the path of the asteroidbefore it destroyed Earth. The weapon worked and Kimura was propelled tounprecedented celebrity status, revered as a saint for the next four decades.

The narrator was recruited as Kimura’s head ofsecurity when she was receiving death threats and has been her right-hand manever since, switching between the roles of bodyguard and assassin as required. Onceprotecting her was no longer a full-time job, he returned to his police duties,but received a call asking for his services again immediately before the novelbegins. The narrator arrives too late, discovering Kimura dead in her home,literally cut to pieces in a hibernation chamber that extends the lifespans of 'The Money' (the socioeconomic elite) in the 22nd century. (It is notdifficult to imagine Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg working onsomething like this in the near future, if they aren’t already). Later, he receivesa posthumous message from Kimura, asking him to find her daughter, also namedAscalon, in order to apologise to her on Kimura’s behalf. He is shocked at therevelation as he has no knowledge of the child and realises that he did notknow Kimura nearly as well as he thought. The story is set in motion veryquickly, in the first four pages, and by the end of the first third of thenarrative the narrator has resigned from the police and accepted his twofoldmission, to detect Kimura’s killer and to find her daughter. Despite beingadvertised as a ‘neo-noir procedural’ – an appeal to the many fans of RidleyScott’s Blade Runner (1982) and its sequel – the novel is very much inthe hardboiled detective genre, with the protagonist driven by both rather thanjust one of the two standard plot devices, the murder mystery and the missing person, remindingme of both Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1939) and Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (1987). In keeping with the finest traditions of hardboiled detectivefiction, the narrator is a complex character with a tainted past and hiddendepths, in addition to an idiosyncratic type of synaesthesia that gives him ahead start against other detectives.

McKinney not only sets the plot in motion withease and expertise, but handles the exposition effectively and economically. Bythe seventh page one already has a good grasp of his 22nd century, including Kimura’s unique status, the preference for living in submarine high rises, theexistence of suits that control one’s environment completely, the ability to prolongthe human lifespan artificially, and much more. Again, it is a testament toMcKinney’s literary skill that he is able to communicate so much so quicklywithout committing the creative writing sin of ‘information dumping’. My solecriticism of the novel is that while the worldbuilding is for the most partconducted with a light touch, it never stops (chapter 21 of 27 is, for example,mostly exposition) and the cumulative effect is a little like wading throughwater: unusual and pleasing at first, but becoming gradually more exhausting asone continues. Notwithstanding, Midnight, Water City is a seamless blendof crime, science fiction, and social commentary that can be read as either thefirst in the trilogy or as a standalone mystery. The novel has been widely andgenerously reviewed since publication and received as much – if not more –praise from crime fiction critics as science fiction critics.

March 21, 2025

Haunted House by J.A. Konrath (independently published) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Figging and maniacal ghosts: horror/thriller uses well-developed characters and strong plotting to bring life to haunted house trope.

Figging and maniacal ghosts: horror/thriller uses well-developed characters and strong plotting to bring life to haunted house trope.Everybody knows that you don’t go to Butler House, a supposedly haunted mansion on a former slave plantation in South Carolina. It’s also the perfect setting for a fear experiment conducted by Dr. Forenzi. Haunted House, the sixth twisty instalment in The Konrath Dark Thriller Collective, brings together characters from throughout the country (and from the previous books). Each of them is offered a monetary award plus a bonus in exchange for participating in the experiment: the alcoholic mother will get reunited with her child, the disgraced molecular biologist will get his old research job back and so on. All of it seems a bit shady.

Konrath effectively delays conflict by building suspense as he delves into characters’ backstories and problems to align the reader with them. The novel also explores the history of Butler House and how its sadistic owners psychologically and physically tortured slaves. Additionally, each fear experiment participant has already faced a hellish ordeal ranging from being locked in a basement with a maniac to being trapped on an island with a cannibal who files his teeth. You’re with these characters, and you want them to escape.

When the key players arrive at Butler House, they encounter other, more typical horror characters: a skeptical author, a specialist in debunking paranormal phenomena, and of course, a medium. They also meet the boisterous prostitute-turned-dominatrix call girl Moni, a major source of comic relief. Participants are allowed to bring one weapon; Moni brings a plunger full of heroin. She repeatedly refers to something called “figging” that she does with her male clientele. Konrath plays with the reader by withholding the definition of this term – can you resist looking it up until the novel ends?

The participants find themselves in a 13 Ghosts type of environment, with the spirits from the house’s sordid past supposedly rising up to terrorize them. A giggling, bare-chested guy who wears a gas mask, smells like meat and enjoys cutting himself with a cleaver. A slave driver who uses a whip and has a patch over one eye. A vengeful slave with four arms stemming from a Civil War-era experiment. Konrath keeps the reader wondering: is what is happening real, or is it a trick to frighten the subjects? The dangers escalate, and the prospect of escape decreases. All the while, the reader roots for the underdogs.

The cop Mankowski seems the most grounded of the characters. In one scene, there’s a fascinating interaction with a serial killer in prison. The killer relishes telling Mankowski the awful things he’s done to his victims.

A group of strangers getting trapped in a threatening environment has been done many times but rarely so entertainingly. Douglas J. Ogurek ****

March 6, 2025

The Terror of Blue John Gap | review by Rafe McGregor

Theaker’s Paperback Library, 148pp, £7.54, July 2010, ISBN 9780956153326

The Victorians were obsessed with doubles, whetherthe literal evil twin brother of the doppelgänger popularised by E.TA. Hoffman,Edgar Allan Poe, and Oscar Wilde or the figural pairing of the civilised andthe savage in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Edward Prendick and Dr Moreau, and CharlesMarlow and Mr Kurtz. Conan Doyle was no exception to the rule. Doubles appearin two of his Sherlock Holmes stories, ‘The Final Problem’ (1893) and ‘TheAdventure of the Creeping Man’ (1923), in the pairing of Holmes and Professor Moriartyand Professor Presbury and Presbury-on-serum respectively, and the fact that DrWatson never sees Moriarty raises the intriguing possibility that he isactually a doppelgänger. Doyle also deployed doubling in his horror fiction,most notably in ‘A Pastoral Horror’ (1890) – Father Verhagen anddiseased-Verhagen – and ‘The Terror of Blue John Gap’ (1910), both of which Iselected for Theaker’s Paperback Library’s TheConan Doyle Weirdbook.

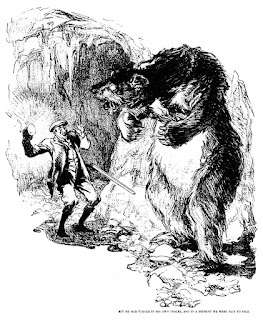

‘The Terror of Blue John Gap’ is an epistolary noveletteof just over seven thousand words, which is divided into seven diary entries byDr James Hardcastle, from 17 April 1907 to 10 June 1907, bookended by a forewordand a single-sentence conclusion by an implied author. Although Hardcastle isintroduced as a man of science, he was terminally ill with tuberculosis at thetime of the events chronicled and the story is replete with suggestions that heis an unreliable narrator. The repeated reflections, allusions, and intimationsof mental illness are matched by a carefully constructed undermining of thepossibility of corroboration. Hardcastle thinks he hears, sees, and shoots ablind, ‘bear-like’ beast taller and broader than an elephant and ten times thesize of the biggest bear, but all the reader knows for certain is that heentered Blue John Gap mine, fell, and lost consciousness. Hardcastle first hearsabout the beast from a young man named Armitage on 17 April, when he favoursprosaic explanations of missing sheep and a damaged wall. By 3 May, Armitagehas himself disappeared and Hardcastle leaps to the completely baselessconclusion that the beast is responsible. Hardcastle’s shot either misses orfails to draw blood and his vague description of his own wounds – concussion, abroken arm, and two broken ribs – is ambiguous as to whether they were causedby a swat from a gargantuan mole or a fall down a mine shaft. Finally, thelocals are quick to dissuade ‘adventurous gentlemen’ from descending on theirpeaceful haven in the Derbyshire Dales and repair the gap to prevent anyfurther exploration.

I’m increasingly convinced that Doyle’sachievement is similar if not identical to that of Henry James in The Turnof the Screw (1898), where the interpretations of psychological and supernaturalhorror are equally valid to the extent that the ambiguity is constitutive ofthe work’s literary value. If the beast is an overgrown figment of Hardcastle’simagination, then it is likely the product of his unconscious and ‘The Terrorof Blue John Gap’ a psychological horror story. Hardcastle is exemplary of theVictorian gentleman, a well-educated and well-mannered man of reason with asteadfast moral compass, a propensity for bold action when provoked, and thegender, class, and ecological prejudices of his time. As he narrates themajority of the narrative, the reader becomes acquainted with both his actionsand his thoughts. The beast, in contrast, remains entirely enigmatic, with muchof its appearance left to the reader’s imagination and scant explanation of itsevolution, habitat, or behaviour. It is, in short, wholly Other to humanity ingeneral and Hardcastle in particular. If the beast is real, then the narrativerecalls the novels of one of Doyle’s contemporaries, H. Rider Haggard, whoseserial protagonist Allan Quartermain is the archetypal Great White Hunter. For Haggard and the majority of Victorians, naturewas simply a resource to be mastered, adapted, and exploited for humanity’s benefit,notwithstanding the widespread acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of naturalselection. Yet Doyle’s perspective on the relation between Hardcastle and thebeast, whether mental or material, is much more sophisticated and explored witha calculated literary artifice that employs two converging configurations.

First, he distances his readers from Hardcastle asthe narrative progresses, a cumulative effect achieved by the combination of repeatedreferences to his unreliability with an escalation of his obsession to uncoverthe mystery of the mine, an investigation he is patently unfit to undertake. Hardcastleis most unsympathetic in his determination that Armitage has fallen victim to thebeast, convincing himself that the beast has taken Armitage in order to justifythe satisfaction of his own desire to hunt and kill it. Second, Doyle invites readersto empathise with the beast by means of the late revelation of itsvulnerability (blindness) and the even later speculation as to its origin(earthly not infernal). The epistemic ambiguity is thus extended to the ethicaland the story closes with the question of whether our sympathies should liewith the beast or with Hardcastle. The beast is the most complex of Doyle’sdoubles because in spite of representing the brutish, savage, and untamedaspects of humanity, it is not presented as meriting approbation – likediseased-Verhagen, Moriarty, and Presbury-on-serum. As such, the doubling ofHardcastle and the beast is an instantiation of what Mark Bould refers to asthe environmental uncanny in The Anthropocene Unconscious: Climate Catastrophe Culture (2021): the recognition by human beings that they arein the presence of nonhuman agency, which draws attention to the play ofidentity and difference between human and nonhuman. Whether produced byHardcastle’s unconscious or by natural selection, the beast sheds light on therelation between the human and the natural worlds.

It would be stretching credulity to categorise ‘TheTerror of Blue John Gap’ as eco-fiction – fiction that takes the integrationand interdependence of humanity and the environment as its subject – butDoyle’s deployment of doubling in the novelette is distinct from the otherthree examples I cited. Diseased-Verhagen is a serial killer, Moriarty an evilgenius, and Presbury-on-serum a rapist-in-waiting. The beast is neitherhomicidal nor evil nor rapacious. While the zoocidal Hardcastle’s agency isimpaired by his obsession, the beast has sufficient control of its instincts torefrain from making a meal of his unconscious body. That ‘awful moment when wewere face to face’ is likely to have been awful for each of the doubles, thepair of which provide a reminder of the invisible ties among all livingspecies.

February 11, 2025

The Accident Season by Moïra Fowley-Doyle (Kathy Dawson Books) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Young adult novel hides sexual and physical abuse within a bubble gum wrapper of tarot cards, costume parties, kissing and witches.

Young adult novel hides sexual and physical abuse within a bubble gum wrapper of tarot cards, costume parties, kissing and witches.The Accident Season focuses on a trio of Irish teens: seventeen-year-old narrator Cara Morris, her best friend Bea (a witch — not the supernatural kind), and Cara’s ex-stepbrother Sam whose crush on Cara is abundantly clear.

Every October is “accident season” for the Morrises due to the inordinate number of negative happenings: cuts, broken bones, severed relationships, and worse. This accident season, according to Bea’s tarot cards, is going to be awful.

The trio undertakes a quest to find classmate Elsie, an outcast who keeps cropping up in Cara’s photos. Elsie has no friends, and yet people know her as the girl who oversees the school library’s “secrets booth.” Here students type out their secrets and give them to Elsie to keep safe. After her father died, Cara was friends with Elsie, who is fading into the shadows – Cara can’t even remember the semi-doppelganger’s last name.

The novel also explores the somewhat forbidden attraction between Cara and Sam – his father Christopher was married to Cara’s artist mother, but he left abruptly. The mother has assumed guardianship of Sam. Then there’s Cara’s sister Alice, dating a handsome and manipulative older vocalist from a band.

The Accident Season contains lots of talk about masks and hiding one’s true feelings. The Cara/Bea/Sam trio isn’t very popular, but it hosts the Black Cat and Whiskey Moon Masquerade Ball, the point of which is that attendees will take off their figurative human masks to show what they really are. And they’re gaining popularity because of it.

The tension escalates as things come to the surface near the end, but until then, it’s a rather dull read. One can take only so much hanging out and smoking and drinking and tarot cards and writing poetry.—Douglas J. Ogurek***

January 21, 2025

Suckers by J.A. Konrath and Jeff Strand (independently published) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Stupid. Ridiculous. Brilliant.

Stupid. Ridiculous. Brilliant.This collection alternates stories between comedy horror masters J.A. Konrath and Jeff Strand, then culminates with “Suckers,” a cowritten longer piece in which their recurring characters Harry McGlade (Konrath) and Andrew Mayhem (Strand) meet and undertake an absurd caper.

Though each author’s work is distinctive, what unites them is playfulness with language, an avoidance of pompous prose, a comedian’s recognition of everyday absurdities, and often, a deliberate imbecility. “The pain was painful,” observes Konrath’s detective, while Strand’s protagonist, more of a sharp albeit regular guy playing at detective work, questions “fun size” Halloween candy – if it was fun, it would be enormous. Throughout the collection, the action moves quickly, and the dialogue stays tight and rapid fire.

McGlade is the ultimate jerk. He’s also highly amusing. He’ll check out a woman’s legs while she’s crying or insult someone at their first meeting. He makes fun of others, whether they’re wearing too much makeup or have a face resembling a percussion instrument. He’s a chauvinist and a womanizer, and he doesn’t pay attention to others. At one point, he even admits to lying to the reader.

Mayhem, on the other hand, is analytical and talky. He points out contradictions in things people say to make them look foolish. He’s also inventive when it comes to defending himself, whether that means using a hardcover copy of Stephen King’s The Stand or a box of grape juice. And Mayhem is more of a family man… but he’s not beyond showing his young son a movie called Blood Blood Blood.

The differences between the two authors surface in the first two stories. Konrath’s “Whelp Wanted,” in which McGlade is tasked with finding a missing dog, takes place over multiple days. He does shoddy research and makes several mistakes. “Poor Career Choice” by Strand is a dialogue-heavy but by no means dull exchange between Mayhem and a would-be assassin who shows up at his home. The action takes place in real time.

McGlade gets more entertaining as the collection progresses. “Taken to the Cleaners” introduces another incompetent hitman. An attractive young woman who is the wife of a chicken king wants McGlade to kill the man her husband hired to kill the man she hired to kill him.

In “A Bit of Halloween Mayhem,” Strand’s protagonist and a friend decide to explore a supposedly haunted house. Strand demonstrates the silliness of two grown men doing something kids are more likely to do.

Next up is Konrath’s “The Necro File,” a magnum opus of humour, disgustingness, and authorial mischief. Client Norma Cauldridge, to whom McGlade repeatedly refers as “Drawbridge” (not to be funny but rather because he’s sloppy), wants him to follow her necromancer husband. This is Richard Laymon level stuff topped with a hearty portion of urine, barf, and poop. Moreover, the story exemplifies that going off on tangents isn’t always ineffective. McGlade, for instance, rambles on about the unappetizing look of hot dogs before eating three of them.

“The Lost (For a Good Reason) Adventure of Andrew Mayhem” recounts how the protagonist met his friend Roger in school detention at age thirteen. They get into trouble when they discover a naked neighbour thrusting around a butcher knife while talking to himself.

In “Suckers,” the two characters inadvertently meet when Mayhem, running an errand involving spaghetti sauce and mushrooms, confronts McGlade intent on rooting out some “pires” (aka vampires). The reader gets the best of both worlds with the witty Mayhem and the not-as-smart-but-still-absorbing McGlade, who often bends the truth to make him seem more heroic than he is.

The story takes a giddy sidetrack when it introduces email communications between the protagonists and their editor Chad. Mayhem begins commenting on the falsity of McGlade’s version of events. When the story resumes, McGlade mocks his coauthor by engaging Mayhem in over-the-top actions inspired by his email comments.

The book ends with Strand interviewing Jack Kilborn (Konrath’s pen name) via email about a forthcoming novel. The exchange has them poking fun at each other and getting silly.

Both authors brought their A game to this collection, whose adventurousness and friskiness enthral the reader’s inner child. Douglas J. Ogurek *****

January 13, 2025

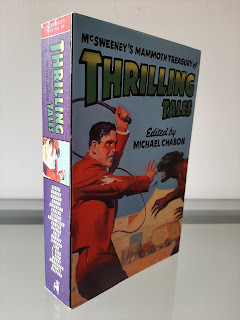

McSweeney's Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales | review by Rafe McGregor

TimothyMcSweeney’s Quarterly Concern is an award-winning American literary journalthat was founded by award-winning and bestselling author Dave Eggers in SanFrancisco in 1998. Eggers has a long and varied bibliography, but is probablybest known for A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, a memoirpublished in 2000. More important than any of this is the fact that McSweeney’swas StephenTheaker’s inspiration for TQF, which he launched with John Greenwood in Birminghamin 2004. As regular readers of TQF (but probably not McSweeney’s) will know,Stephen’s secondary goal (after keep it going)was to catch McSweeny’s up, which he achievedin 2011. At the moment, TQF is in the lead – but only just – with seven-sevenissues to McSweeney’s seventy-six. The next issue of McSweeney’s,which is due in February, will see a new editor, novelist and academic RitaBullwinkel, take the helm. One of the features that distinguishes McSweeney’sfrom other literary journals is Eggers’ novel approach to editing andproduction:

McSweeney’s Quarterly Concerncontinues to publish on a roughly quarterly schedule, and each issue ismarkedly different from its predecessors in terms of design and editorialfocus. Some are in boxes, others come with a CD, still others are bound with agiant rubber band, and perhaps someday an issue will be made of glass.

Why the hell not!

The inspiration for TQF is not just any old McSweeney’s,but issue ten, McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales, which wasguest edited by champion of genre fiction Michael Chabon and published in February2003 (a little over a year before the launch of TQF). It is easy to see why…froma garish cover borrowed from the October 1940 issue of Red Star Mystery Magazineto Chabon himself as editor to four hundred and eighty pages’ worth of twenty stories,some great illustrations, and contributors that include: Michael Crichton,Harlan Ellison, Neil Gaiman, Nick Hornby, Stephen King, Elmore Leonard, and MichaelMoorcock. I’ve no idea how deep McSweeney’s pockets are, but one wouldbe hard-pressed to compile this kind of lineup with literally unlimitedresources. Most of the tales don’t disappoint regardless of the stature oftheir authors and I agree with Stephen that this is one of – if not the –best collections of short fiction ever published for pulp fiction fans.

My favourite tale is the first, Jim Shephard’s ‘Tedford andthe Megalodon’. As a sharkstory enthusiast, I wondered how much of the visual horror and signaturesuspense would be retained in the short story format (on which note the illustration,by Howard Chaykin, is a perfect accompaniment, breathtaking without being a spoiler).Simply stated, neither the horror nor the suspense are lost and the lastsentence is one of the most chilling conclusions to a narrative I’ve ever read,all the more remarkable because it is not unexpected. Honourable mentions aboveand beyond Shephard’s illustrious peers go to Hornby, for ‘Otherwise Pandemonium’;Kelly Link, one of the pioneersof the New Weird, for ‘Catskin’; and Moorcock, for ‘The Case of the NaziCanary’. Moorcock’s contribution is an outing for his occult detective, SirSeaton Begg, AKA the other Baker Street detective, Sexton Blake. King’scontribution, ‘The Tale of Gray Dick’ features Roland Deschain, protagonist of TheDark Tower series, although as I’ve only read the first two books, I’m notsure where it fits chronologically (he is already missing some fingers, if thathelps anyone work it out). I was only disappointed twice: Eggers’ contributionis, to my mind, out of sync with the rest, too slow and too long, and I foundEllison’s contribution insubstantial and just not very funny (assuming the aimwas comedy). McSweeney’s #10 is now out of print (along with the rest ofthe first thirteen issues), but used copies remain available from the usualvendors and are, at the time of writing, still relatively cheap (the upper endof the range I saw was £20, postage excluded).

Having set such an incredibly high bar, has TQF ever comeclose? No doubt I’m biased because it featured one of my RoderickLangham stories, but I don’t think TQF#50,which was published in January 2015, was too far off. Aside from the elevenstories in three hundred and twenty-four pages, which include a few of mypersonal favourites, I very much enjoyed its showcasing of so many of themagazine’s regular contributors, including several whose collaboration withStephen and John predates my own (which began with a single and somewhat scantreview in TQF#23in 2008). That said, I have particularly high hopes for TQF#80, which is dueshortly. The last page of McSweeney’s #10, the source of my quote above,states that (only) fifty-six issues were planned. When McSweeney’s #56 waspublished in 2019, the (true) goal was revealed as one hundred and fifty-six. Perhapswhen that issue is published, it will be two hundred and fifty-six. Let’s hopethat day comes and that, as Stephen puts it, both McSweeney’s and TQF keep going.