Stephen Theaker's Blog

October 16, 2025

Rainforest | review by Rafe McGregor

Rainforest by Michelle Paver

OrionBooks, hardback, £20.00, October 2025, ISBN 9781398723207

MichellePaver is an Oxford educated British author best known for her Chronicles ofAncient Darkness, a children’s fantasy series of nine books that began withWolf Brother in 2004 and concluded with Wolfbane in 2022. Thenovels are aimed at children from the ages of nine to thirteen, have beentranslated into thirty languages, and have sold over two and a half millioncopies. Paver has also published Daughters of Eden, an historicaltrilogy; Gods and Warriors, an historical series for children; and fivestandalone novels. All of her published work is historical in setting, albeitvarying dramatically, from six thousand to one hundred years in the past. Amongher standalone novels, three are horror stories: Dark Matter (2010),which is set in the Arctic in 1928; Thin Air (2016), set in theHimalayas in 1935; and Wakenhyrst (2019), set in the fens of EdwardianSuffolk. Dark Matter and Thin Air are two of the best horrornovels (or, more accurately, novellas) I have ever read. Until reading DarkMatter shortly after it was published, I’d considered James Buchan’s TheGate of Air: A Ghost Story (2008) my favourite contemporary horror story, but unlike the latter, Dark Matter and Thin Air have rewardedrepeated readings. Wakenhyrst is longer than its predecessors and of asimilar quality, although I found it harder going, which is because of myindifference to the haunted house trope rather than because of any flaws. (Imust confess that even Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House andRichard Matheson’s Hell House leave me cold…and I’m not referring to myspine.)

Rainforest is Paver’s twenty-third novel, sixthstandalone novel, and fourth horror novel. It also completes an informaltrilogy with Dark Matter and Thin Air, all of whom are about andnarrated by well educated, old fashioned British men who have difficultysocialising and lead conflicted inner lives. Writing with and in the voice ofanother gender is, I think, very difficult and Paver is one of the fewauthors to succeed completely. All three novellas (Rainforest is longer than the other two, but still a novella) read exactly as if they’d beenwritten by the protagonists Paver has presented with such and competence and convictionand all three are men we wouldn’t want to spend much time with, but whose livesare nonetheless captivating and compelling. The three novellas also demonstratean enviable expertise in representing the experiences of living and working ininhospitable environments – whether icy in temperature, high in altitude, or crushingin humidity – without resorting to lengthy exposition. Rainforest is, asthe title suggests, set in the Mexican rainforest, very likely the LacandonJungle, which was part of the Maya civilisation in the preclassic period, in1973. Dr Simon Corbett is a forty-two-year-old entomologist from Cambridge who specialises in the predation of mantids or Mantidae (praying mantises). Whenwe meet him, he is recovering from a mental health crisis connected to thedeath of a woman named Penelope and en route to an archaeological dig inthe jungle, where he hopes to both recover his equilibrium and resurrect astalled academic career.

Corbetthas been advised to keep a journal by his doctor and that journal is what constitutesthe majority of the novella. Penelope was, it appears, Corbett’s firstgirlfriend, which is the first suggestion of how much of a misfit he is (theirrelationship and her death both being recent). He also disapproves of the cultural,social, and political changes of the preceding decade, dislikes the IndigenousPeople of Mexico (a typically baseless and irrational racism), and is frightenedand disgusted by their ancient and contemporary rituals of self-mutilation. Paveris often compared to M.R. James and while there is definitely a ‘Jamesian’ atmosphereto and in her horror, there is also a ‘Lovecraftian’ scope and more accurate descriptionis that she combines the virtues of both masters of the weird tale with acontemporary sensibility and sensitivity in a way that may well be unique. Theplot of Rainforest is driven by the subtle integration of twonarratives. The first is in the present and follows Corbett’s journey to thecamp, tensions with both his British and Mexican coworkers, and his unsuccessfulsearch for mantids. While these events are unfolding, he also becomes more openabout his past with Penelope, revisiting and revising what he has previouslyrevealed. Penelope, it turns out, was an acquaintance not a lover and her deathin a car crash occurred in the course of her flight from Corbett.He is, indeed, a stalker, who became obsessed with her after a single, short dinnerdate and who was the recipient of a lawyer’s letter and a policecaution. The pull and push between present and past, effect and cause,representation and reality retrospectively infuses previous passages with new (andsinister) meaning while heightening the narrative tension. To take just threeexamples, the novella opens with Corbett fondling something he calls his‘talisman’. I’ll avoid spoilers by not revealing precisely what it is, sufficeto say that the object seems to be a bizarre but harmless keepsake. Similarly, hisentomology seems to be a relatively insignificant part of his personality,perhaps even a narrative device to bring him to the jungle, but his expertise in mantid predation is no contingency. Finally, Corbett's reaction to an illustrationin a book seems either absurd, tangential to the plot, or both, but is a crucialcomponent of the narrative crisis.

WhileRainforest is neither didactic nor even a case of the ‘instructing bypleasing’ tradition of literature, it does explore a theme that is relevant toand resonates with everyday life in the twenty-first century. The novella exploresthis theme in a singular and inventive way and simultaneously reinvents theghost story as an aesthetic form. First, Paver asks us to reconceive or atleast reconsider ghosts as stalkers. Not stalkers in terms of the denotation ofthe word, the hunting of humans or animals by other humans or animals, but inthe legal connotation of men stalking women with whom they have becomeobsessed. Regardless of whether they were perpetrators or victims, ghosts aredead things that are obsessed with an aspect of their animate lives – eitherwith the places where they lived or died or with people whom they despised orloved. Like the stalker, the ghost is an unwelcome and uninvited presence thatdisturbs and disrupts the mental (and sometimes physical) wellbeing of theperson it haunts or of the people who enter the place it haunts. Aside from andin addition to the richness of this thematic exploration of what ghosts are,Paver reverses or inverts the traditional ghost story in and with Rainforest,presenting her readers with a (living) person stalking a (dead) ghost. Whereone might expect Penelope to stalk Corbett from beyond the grave in revenge, itis Corbett’s pathological fixation that fails to recognise death as animpediment. As he stalked her in life, so he continues to stalkher in death, deluding himself that he is driven by guilt rather than acceptinghis predatory desire to possess her against her will. I can’t recommend thisbook enough. If you haven’t yet discovered the pleasures of Paver,follow up with Thin Air, Dark Matter…and Wakenhyrst too.

October 3, 2025

The Strigun's Cartography Workshop | review by Rafe McGregor

The Strigun's Cartography Workshop: Maps for Novels, Board Games, D&D Campaigns, or Decoration

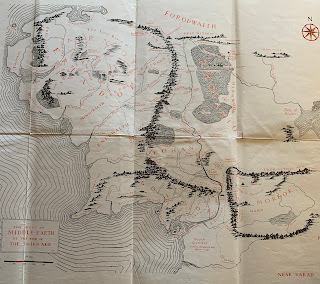

In Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s alter ego, Charles Marlow, describes himself as being fascinated by maps from an early age – particularly maps with blank spaces – and such fascination has probably accounted for a great deal of harm over the centuries. It certainly seems to have been shared by many people across multiple generations. My own interest in maps was much more limited and less consequential and I only ever saw them as a tool for orienting myself until I came across what I later realised were world famous: J.R.R. Tolkien’s maps for first The Hobbit and then The Lord of the Rings. This must have been sometime in the late seventies and the latter were tucked into the dustjackets of the editions my parents kept at home (probably from the nineteen sixties). There were two different maps and I can’t remember which map was in which part of the trilogy, but I reproduce the better-known one here (above).

Later, I discovered Fighting Fantasy, Lone Wolf, and Dungeons & Dragons and began to appreciate the artistic qualities of maps a little more. They nonetheless remained first and foremost a way of orienting myself, to the wonders of an unexplored fantasy world, even though I recognised that Lone Wolf and the AD&D Greyhawk campaign maps in particular had an aesthetic appeal beyond the practical. When I replaced the editions of The Lord of the Rings, I kept the maps from the originals. I’m not entirely sure why, but I still have them.

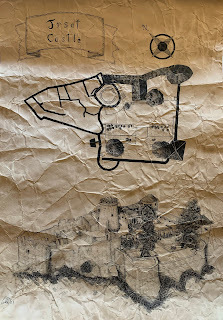

Later, I discovered Fighting Fantasy, Lone Wolf, and Dungeons & Dragons and began to appreciate the artistic qualities of maps a little more. They nonetheless remained first and foremost a way of orienting myself, to the wonders of an unexplored fantasy world, even though I recognised that Lone Wolf and the AD&D Greyhawk campaign maps in particular had an aesthetic appeal beyond the practical. When I replaced the editions of The Lord of the Rings, I kept the maps from the originals. I’m not entirely sure why, but I still have them. Earlier this year, I visited friends in Croatia and met Endi, the proprietor of The Strigun’s Cartography Workshop, in Trsat in Rijeka. I had been told that he created maps to order, but didn’t think too much about it and, if I remember correctly, most of our conversation was about film, one of several shared interests. He was, however, kind enough to give me two of his maps as a memento of my visit, one of Trsat Castle, which looms over Rijeka like an eagle on its perch, and the other of the province of Istria, where I visited Pula, which boasts an almost entirely intact Roman amphitheatre.

I didn’t get the chance to look at them properly until I returned home, when I was awed by their beauty. The photographs (above and right) do not do them justice and they are as pleasing as artifacts to hold and touch as they are works of visual art. Had I greater expertise in the visual arts, I could describe them more eloquently, but one does not need to be an afficionado to recognise their quality. I was, of course, struck by the similarity in style to Tolkien, though when one compares and contrasts the two, Endi is clearly the superior artist. In addition, he will make maps to order and his website is well worth browsing, whether for a commission or just for pleasure. The maps are divided among regions, cities, and battles and there is a separate page for the work he has had published to date. As the website reveals, the Strigun’s maps come in both two-tone and full colour and there is even a map for Game of Thrones…how could there not be!

September 18, 2025

Dating After the End of the World by Jeneva Rose (Montlake) | review by Stephen Theaker

Amazon Prime subscribers currently get at least one book free to own each month, sometimes two. I tended to claim but not read them, but they have started to include more novellas and short stories, and that has led me to read outside my usual genres, which I appreciate. One thing immediately obvious to anyone looking at Amazon First Reads is that the books on offer are virtually all by female writers, and aimed at female readers, with female protagonists. One can only assume Amazon follows the data in that respect, which is interesting.

This book fits that pattern, but that’s not to say male readers can’t enjoy it too. I did, to a certain extent. It begins with a scene in September 2009, when our Wisconsinite protagonist was thirteen years old and getting fed up with her doomsday prepper dad. They are building a perimeter fence but Casey would rather be having fun. She’s getting bullied at school by kids who think her dad is weird – and you know what, she thinks he’s weird too. Skip forward to 2025 and Casey is Dr Warner, working in a hospital, and not talking to her dad very often.

Then the apocalypse happens: it always does, if you wait long enough. Patients start biting, she flees the hospital, and for the next six weeks she shelters with her fiance Nate in their apartment. Help never comes, but it gives her time to observe what’s happening in the city. Those bitten either survive, apparently unharmed, or lose their memories, or turn into the ravenous biters. Some survivors are like Casey and Nate, just regular people trying to survive. Others have become burners, out to kill and destroy as if Mad Max were their Emily Post.When three burners find her hideout, Casey realises it’s time to return to Wisconsin, and her dad, and the safety of the farm she helped to fortify as a teenage girl. What she doesn’t know is that Blake Morrison will be there. Leader of the bullies that tormented her. The boy who ruined her life. Sharing her room. He still has the same evil smirk, but now he’s her dad’s best friend, the farm’s most important protector, and so hot she can’t even look at him without melting into a puddle. Can she get over her anger towards him, even for her dad’s sake? Does she want to?

Despite the gore and the reasonably explicit sex, this book felt like it was pitched at the reading level of younger teenagers, which made for an easy read, even if it felt a bit patronising. Perhaps that reflects how Casey herself seems to be stuck in teenage mode, which becomes aggravating when she refuses to listen to anyone’s safety advice, or learn the rules properly, or pass on information she has, with fatal consequences in some cases – she doesn’t even tell them about the burners. It makes her quite an unlikable lead.

On the other hand, the author writes a good enemies-to-lovers story, and although I am not a regular reader of romance novels, I found Casey’s hatred of Blake and her attraction to him both equally believable, and by the end I was hoping they would find a way to make things work. The book parcels out episodes from their teenage years in a way that smartly creates a degree of tension, since you can’t quite know if rooting for their relationship is at all the right thing to do. A charming supporting cast round the book out nicely. An easy, fun read. Stephen Theaker ***

September 14, 2025

Kindle Scribe (2024 Release, 64GB) | review by Stephen Theaker

I always regretted not buying the Kindle DX, for its big e-ink screen, so when the Kindle Scribe came out I was tempted. But I already had a Boox Note 2 (“BN2”), which does all the same things and much more besides, being an Android e-ink tablet rather than just an ereader. So I didn’t buy a Scribe until its second edition came along, it was on sale, and I was offered a substantial discount in return for trading in my Kindle Oasis. The Oasis was nice to read on in summer, but it got too cold on winter nights, so off it went.

The most important aspect of any ereader is the screen, and the clarity of text, and on the Scribe text looks pristine at larger sizes, backlight on or off, and also at smaller sizes in two columns to create a more bookish reading experience. Comics look terrific too, especially if you pick out a black-and-white book with nice square panels, or with a small enough page size to be readable a page at a time. I’ve read dozens of manga books this year as a direct result (the highlights have been Nina the Starry Bride, Witch Hat Atelier and Space Brothers).

As an ereader, then, I love it, though not unreservedly. As your only ereader, its weight can become an issue – my hands began to ache after a while – and it’s far too big and fancy to read at the bus stop (though I have taken it to the pub lots of times). I miss the home button from the BN2, and the page-turn buttons from the Kindle Oasis. You can remove white borders on some fixed-format books, but not always, and it’s unreliable: in manga books it crops off part of the picture too often to be useful.

Then we get to the reason it is called the Kindle Scribe: you can write on it, with a stylus. I bought the 64GB edition that came with the Premium Pen, which has an eraser and a customisable button, which I have set to highlight. The pen is a good one, nice to hold, and works with my BN2 as well, while the BN2 pencil works with this in return. I love writing on the Kindle Scribe screen: it has a bit of drag that’s not there on the BN2 or an iPad. Unlike the BN2, you cannot connect bluetooth keyboards and page turners to the Scribe for typing and navigation.

You can use the pen for writing in ebooks (including personal documents), annotating pdfs and writing in notebooks. At first I was enthusiastic about all three. In fact I used it for annotating an entire ebook I was working on, but that turned out to be a miserable mistake, the notes exporting in a way that made it very difficult to work from them. Now I only really use the sidebar, for quick notes on story submissions, which at least show up on the iPad app and can be worked through there.

Annotated pdfs look pretty good on the Kindle Scribe, but the pdfs export with each page and its annotations as one picture, so you can’t work through the annotations in say Adobe Reader. Fine, I thought, I’ll go back to the old British Standard proofreading marks, draw on the proofs I’m checking, put annotations in the margins. The only colour is black, but it was just about okay. Except that if you switch to landscape view on a page, the pdf exports with that page awry and the annotations out of line.

I delayed this review, assuming that something so basic would quickly be fixed, but so far it has not. If you want something to annotate pdfs on, avoid the Kindle Scribe.

I have more positive things to say about the notebooks, even though they are extremely rudimentary compared to the BN2, with few options and no colours (although the BN2 has a grey screen, you can choose to draw in colour and it will be visible on export). And yet I have used it much, much more for handwritten note-taking than either the BN2 or the iPad, e.g. after watching a film, or during meetings, or making a nightly to-do list for the next day. Perhaps the lack of options makes it easier to get started.

Another reason is that I’m always reading on it, so it’s always nearby, ready for notes, and the pen clips magnetically to the Scribe, so that’s always handy too. Plus, the fact that you can’t do anything else on it other than read and make notes means I use it to read and make notes. It has one advanced feature: it can convert your notes to plain text and email them to you, as I did with the notes for this review. The handwritten text in pdf exports of your notebooks is searchable, which impressed me.

Was it worth trading in my Kindle Oasis and paying £200 extra to get this? Yes, definitely, I use it constantly – although I probably do need a Kindle with a normal-sized screen too to complement it. It’s got me reading, and it’s got me writing. I love it, and I love it more the further I get away from the miserable mistake of having used it to annotate a book for work. The BN2 beats it in dozens of ways, but it also has a better – and hence more diverting! – browser, plus a full range of Android apps. Like the Freewrite, the Kindle Scribe can’t do much, so it keeps me focused on the things it can do. Stephen Theaker ****

September 8, 2025

Megalopolis | review by Rafe McGregor

Self-reflexive or self-indulgent?

Likemany Anglophone readers of my generation, I suppose, I first came across‘megalopolis’ in one of the many Judge Dredd comics published in 2000 ADmagazine during the 1980s. The word was used to describe Dredd’s beat, ‘Mega-CityOne’, a gargantuan city covering the Eastern Seaboard of North America from Miamito Quebec City. I assumed both ‘megalopolis’ and ‘mega-city’ were sciencefiction inventions, but the Oxford English Dictionary taught meotherwise. ‘Megalopolis’ was used as far back as 1828, as a synonym for‘metropolis’, and is now more commonly used to describe the contiguous built-uparea formed when metropolises expand into one another (beginning with LosAngeles in the 1960s). ‘Megacity’ came much later, in 1967, and identifies ametropolis with more than 5 million residents (beginning with the Dallas-FortWorth conurbation). In case anyone is interested, the biggest megacity in theworld is currently Tokyo, with a population of approximately 39 million, andthe biggest megacity in the US, New York, with 19 million. The setting ofFrancis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis is ‘New Rome’, an alternative, futureNew York, and the title also alludes to megalon, a material or mineral withmagical properties that can regenerate and restore both cities and the peoplethat live in them. When the narrative opens, protagonist Cesar Catalina (playedby Adam Driver) has recently been awarded a Nobel Prize for his creation of megalon.

I firstheard about Megalopolis long before it was released in September 2024 –not because of any especially effective marketing strategy, but because of the conditionsof its conception and production. Coppola began thinking about it in the late 1970sand began work on it in the early 1980s. The original idea seems to have beensomething like a cinematic Ulysses (1922), James Joyce’s monumental reimaginingof Homer’s Odyssey in 1904 Dublin (which is, in my opinion, the greatestnovel ever published and ever likely to be published). Joyce’s source materialwas the most celebrated story ever told in the Western canon (or the second mostcelebrated, if you prefer the Iliad, which most scholars don’t), butCoppola’s was a curious choice. He had already tried something similar with ApocalypseNow (1979), a magnificent reimagining of Joseph Conrad’s brilliant novella,Heart of Darkness (1899), in South-East Asia during the Vietnam War. Megalopoliswould, in contrast to both Apocalypse Now and Ulysses, reimaginea historical event, the Catilinarian conspiracy in the Roman Republic of 63BCE, in a faintly futuristic New York. The conspiracy was an attempted coupd’état by Catilina, aimed at seizing power from consuls Cicero and Hybrida,and never passed into popular culture. (Though I consider myself an amateurhistorian, I had to look it up). Perhaps more problematic, where the monstrouscomplexity of Ulysses is to at least some extent clarified by knowledgeof the Odyssey, knowledge of the historical conspiracy actuallycomplicates the film: the fictional Catalina is called ‘Cesar’, but (Julius)Caesar (who is absent from the film) played a historical part; the attemptedinsurrection is by Clodio Pulcher (played by Shia LaBoeuf) whereas ClodiusPulcher opposed the coup; Hybrida and Cato have no fictionalcounterparts and there are several major characters without historicalcounterparts. Notwithstanding, Megalopolis is a reimagining, of FritzLang’s Metropolis (1927), one of the first feature length sciencefiction films and one of the greatest films ever screened.

Bythe turn of the century, Coppola had decided he would fund his ‘passion’ (orperhaps ‘vanity’) project himself and began shooting cityscapes of New York. Atthe turn of the next decade, he started writing the script. Eight years later,on the day before his 80th birthday, he announced that he’d finishedthe script, raised $120 million for a budget, and was ready to start interviewingactors. Filming began in 2022 and rumours of Coppola’s erratic behaviour soonspread, followed by allegations that he was under the influence of cannabis forlengthy periods, had sexually assaulted extras, and exceeded the budget by $16 million.It’s difficult to know how much of this to take seriously, but when I readabout it, the whole enterprise reminded me of Frank Pavich’s Jodorowsky’sDune (2013), a documentary about Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unsuccessfulattempt to film Frank Herbert’s novel, Dune (1965), in the 1970s. Jodorowsky’sventure was hubristic to the point of insanity, ethically dubious, and doomedto failure, although the documentary acquired both critical acclaim and a cultfollowing. Immediately after watching Megalopolis, I discovered thatCoppola commissioned director Mike Figgis to make a documentary of the makingof his film, which was released this month as Megadoc (2025). I wonder ifCoppola’s motivation for the documentary was vanity or finances? Probably a bitof both.

Megalopolis begins with truly masterful exposition: we are shown almost everything we need to know about what will follow in the first 12 minutes (of 133 from opening to closing credits). One is simultaneously struck by the film’s idiosyncratic yet impressive style, a unique combination of filmed theatre, tasteful CGI, breathtaking cinematography, and beautiful mise-en-scène. Very quickly, we learn that Catalina has a utopian vision for New Rome at odds with Mayor Franklyn Cicero (played by Giancarlo Esposito) and the ability to stop time, which works on everyone except for Cicero’s wayward daughter, Julia (played by Nathalie Emmanuel). The plot is briskly set in motion when Catalina’s ambitious girlfriend, television presenter Wow Platinum (played by Aubrey Plaza), realises he is still in love with his dead wife and seduces his aged uncle, Hamilton Crassus III (played by Jon Voight), the wealthiest man in New Rome. Meanwhile, Crassus’ son, Pulcher, a spoiled wastrel jealous of the success of everyone around him, is desperate to make a name for himself. The ingredients are all simmering in the pot and our appetites whetted for making a meal of what follows. Shortly over half an hour in, the stakes are established as the question of whether or not Catalina will succeed in realising his architectural and humanitarian dream and all of Cicero, Wow, Pulcher, and Catalina’s self-destructive guilt about his wife’s death framed as antagonists or obstacles. Later, Wow Crassus and Pulcher will emerge as the villains of the piece. Later still, they join forces and become an apparently unstoppable dystopian threat that raises the stakes and heightens the tension in an altogether satisfying way. So, what goes wrong?I noted that the reimagined history was confusing. The pseudo-Roman settingconstitutes part of Coppola’s distinctive style, which is pleasing on both theeye and the ear, but otherwise pointless. The same is true of the very limitedadvanced technology that seems to have been responsible for the film beingclassed as science fiction. While megalon is the means by which Catalina intendsto realise his vision, that means could just as easily have been an imaginedbut mundane mineral or a fictional but plausible construction method.Similarly, the sole purpose of Catalina’s ability to stop time as far as theplot is concerned is to show that there is a genuine connection between him andJulia once they fall in love. If I appear overly critical of the film’s retrofuturism,the categorisation as science fiction in particular brings with it certainexpectations, for example that the film will to at least some extent be aboutadvanced technology or about the psychological or political impact (or both) ofthat technology. Futuristic megalon is as incidental as Catalina’s superpowerand, like the Roman retrospection, serves a stylistic function, providingCoppola with the opportunity to present some (once again) aestheticallypleasing CGI. To remain with the plot a little longer, the story is very much thatof Catalina’s ambition and the film a vehicle for Driver as Catalina. In thatpart, he either lacks the charisma or does not bring enough of it to thisperformance to engage and enthral the audience for the quantity and quality ofhis screen time. I found myself much more interested in Julia and Wow, watchingthe narrative as a tug of war between two powerful women with Catalinarelegated to the role of the rope. As a final criticism of the plot, once all islost for Catalina and Julia, the tables are turned by Crassus in a scene thatis absolutely ridiculous. I think it’s meant to be amusing rather thandramatic, a deliberate parody of itself, but it’s neither tense nor funny andfalls flat.

IfMegalopolis is not about the Catilinarian conspiracy and/or itscontemporary counterparts or the impact of advanced technology such as megalon,then what is it about? I mentioned Metropolis earlier and while thereare several references to Lang’s masterpiece (and no doubt some that I missed),Megalopolis does not share its themes. Aside from a few superficialmentions of immigrants being unwelcome and some gratuitous police brutality,Coppola fails to offer a perspective on social justice and does not represent classconflict or even class consciousness. With politics, technology, and justice strippedaway, there isn’t very much left. A theme that emerges with admirable speed inthe expert exposition is some elaboration of the relationship between time andcreation, the latter in the sense of artistic creativity. As the narrativeprogresses, a link is established with first utopian desire and then romanticlove, all bound up within a temporal horizon. Early in the second half of thefilm, Catalina tells Julia, ‘I can’t create anything without you next to me’ andone is inevitably reminded of Coppola’s wife of six decades, Eleanor, to whomthe film is dedicated and who died shortly before its release. The tyranny oftime, the inspiration and perspiration of creation, dreams of a better way oflife, loving as a way of living…Megalopolis is a film about itself,about the trials and tribulations of its own creation. Coppola has fictionalisedhis creative process from conception to production, creating an almost entirelyself-reflexive epic. And while that doesn’t make it a poor film, it does meanthat it doesn’t have very much to say to its audience, not much more than we couldfind in Megadoc anyway.

Thecritical response was initially described as ‘polarised’, but reviews have beenlargely negative, the only notable exception being Sight and Soundmagazine, who placed Megalopolis 17th on their list of thebest 50 films of 2024. To me, ‘polarised’ suggests something broad in scope andrich in depth, a work of boldness and ambition that will either flop or berecognised as a work of genius but could never be mediocre. I just don’t seethis kind of greatness in it. There are plenty of highlights – Coppola’s style,the slick start, Emmanuel and Plaza’s performances – but more lowlights and Megalopolisis neither a magnum opus nor anadir. The film has 45% on the Tomatometer, which is not unfair, though I do wonderif critics would have been more generous if they didn’t know that it was theproduct of 50 years of work. Unfortunately for Coppola, it was also a majorcommercial failure, only recouping £14.3 million at the box office and costinghim $75.5 million by May 2025. At the time of writing, Coppola is 86, whichsuggests that this is his last film. While it’s a shame to see a career endthis way, we should not forget that he is the genius who brought us all three Godfathers,Apocalypse Now, The Outsiders (1983), and Bram Stoker’sDracula (1992), among many others. I hope he doesn’t forget either.**

September 3, 2025

The Ploopy Knob | review by Stephen Theaker

When I tell people that I love my Ploopy Knob, and I can’t stop touching it while I work, they sometimes get the wrong idea. To be fair, when I first heard of it (a science fiction writer was joking about it), I wasn’t even sure the Ploopy Knob was a real device, or if it was an April Fool’s joke. But after I had finished laughing, I looked at the device’s website (https://ploopy.co/knob/), laughed some more (“with a smooth feel and great finish, it’s a Knob you’ll want to touch all day long”), and realised I might actually find it very useful to have a Ploopy Knob. And if it turned out to be a dud, it would be worth the money just for the jokes.

When I tell people that I love my Ploopy Knob, and I can’t stop touching it while I work, they sometimes get the wrong idea. To be fair, when I first heard of it (a science fiction writer was joking about it), I wasn’t even sure the Ploopy Knob was a real device, or if it was an April Fool’s joke. But after I had finished laughing, I looked at the device’s website (https://ploopy.co/knob/), laughed some more (“with a smooth feel and great finish, it’s a Knob you’ll want to touch all day long”), and realised I might actually find it very useful to have a Ploopy Knob. And if it turned out to be a dud, it would be worth the money just for the jokes.So what is it? Simply a knob that you can turn, an accessory for your Windows or Linux computer (it works less well on Mac), about 5 cm in diameter – which is much smaller than I expected, but turns out to be perfect. Built around a tiny Raspberry Pi, many of its other parts are 3D-printed, and the plans are available for users to print replacements if necessary. It’s not wireless: it needs to be plugged into the computer via USB. You don’t grasp the sides of it, usually, the surface is ridged, so that a finger resting on the top of the Ploopy Knob can easily turn it, without losing grip.

Power users can apparently reprogram the device to do different tasks, but that’s not me, I just use it for scrolling through documents while I read them, and yet I am utterly delighted with it. I’ve bought many similar devices over the years – a number pad to which I could assign macros, a rollerball, a mouse pen, and at one point I even had an Xbox controller hooked up to the PC for scrolling around documents – but none of them were ever so much better than the mouse and keyboard that they earned a permanent spot on my desk.

The Ploopy Knob is different. For one thing it's hilarious. Every time I mention it I laugh. This is not something to be underestimated when working. A chuckle a day adds up to a lot of chuckles over a lifetime. But it also fits onto the desk very neatly: I'm right-handed, so my keyboard (a clicky Das Keyboard) is in the middle, the mouse on the right, and the Ploopy Knob sits on the left, taking up very little space and always ready to use. It feels very nicely balanced. There are keyboards that have similar knobs, but that means hovering over the keyboard, whereas the Ploopy Knob can be placed in more pleasurable locations, so reading becomes much more pleasant.

It is also much more precise and sensitive than using a mouse wheel for the same job. So even if all I ever use it for is scrolling through Word files I’m editing and PDFs I’m checking, it was well worth the money I paid (about fifty quid). The only problem is that it's made me so keen to keep reading on the PC that I've tired my eyes out a bit. If I had a job interview now, I would be obliged to ask whether I would be allowed to use my Ploopy Knob in the workplace. Now I'm accustomed to having a Ploopy Knob, working without one would feel like a needless frustration. Stephen Theaker *****

August 25, 2025

Dead Scalp by Jasper Bark (Crystal Lake Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

James Briggs is on the lam, with most of Arizona on his tail, and Mexico is out of reach. But he’s heard about a portal to a magical place where the law can’t reach. So he slices up a rabbit, takes a running jump at a portal, and after a bit of argy-bargy hands over the price of entry to a pair of bearded thugs: Clem and Bart. Clem has been in Dead Scalp forty years, though he looks about thirty. No one ages here, and they don’t get sick, but they can be killed, and the only thing that grows here is hair.

James Briggs is on the lam, with most of Arizona on his tail, and Mexico is out of reach. But he’s heard about a portal to a magical place where the law can’t reach. So he slices up a rabbit, takes a running jump at a portal, and after a bit of argy-bargy hands over the price of entry to a pair of bearded thugs: Clem and Bart. Clem has been in Dead Scalp forty years, though he looks about thirty. No one ages here, and they don’t get sick, but they can be killed, and the only thing that grows here is hair.To make up for bashing Bart, James has to do some work for Bill Baldwin, the boss of Dead Scalp. He’s a real villain, a slave-owner who has had children murdered, and women kidnapped from the outside world to be raped in the town brothel. He is brutal with his punishments for those who step out of line, and the worst of these punishments is called “ingrowing”. There’s a reason all the men in town have beards: something terrible happens when they shave, or when Bill shaves them.

If the town itself wasn’t horror enough, James will soon see how much worse it can get when an ingrown corpse isn’t properly disposed of. And it was his fault…

The cover of this weird western horror novella describes it as “back in print, in a brand new edition”, but this is its first publication as a book in itself, its original release being in the author’s 2014 collection from the same publisher, Stuck on You and Other Prime Cuts. I’m glad that they disinterred it. I’ve read quite a few indie horror books recently and this one had the most startling imagery, the goriest deaths, the biggest surprises, the most shocking ideas.

Some of the human-on-human violence is extremely unpleasant, especially the sexual violence, but in that case catharsis comes when the perpetrator is punished in a horribly appropriate way. Like the much-missed Ash vs Evil Dead, the book has a cartoonish, blood-soaked, over-the-top tone, too demented to be truly upsetting. I loved the intensity of it. It doesn't hold back, doesn't save anything for later, it goes all out in its ninety pages, playing every card as quickly as possible, like a little kid playing Snap. ****

August 21, 2025

A Head Full of Ghosts by Paul Tremblay (William Morrow Paperbacks) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Questioning possession: inventive novel swerves horror trope in new direction.

Questioning possession: inventive novel swerves horror trope in new direction. While getting accustomed to Paul Tremblay’s Bram Stoker Award-winning A Head Full of Ghosts, I kept asking myself: do I like this, or don’t I? The more I read, though, the more I moved towards the “like this” option.

Like many Tremblay novels, this one takes a common horror subject – this time it’s possession – and gives it a twist. A Head Full of Ghosts swerves from the expected, steps back, and, in a way, explores what a possession story is. It starts silly with young sisters Meredith (Merry) and Marjorie telling each other stories about molasses floods or things growing in their house, but the book gradually reels the reader in as things start to go wrong in the Barrett family’s Massachusetts home.

The story hinges on the question of whether Marjorie is possessed or mentally ill. When the girls’ father John loses his job and has trouble finding another, he turns to prayer and becomes a religious zealot. To alleviate their growing financial difficulties, the Barretts become the subjects of a reality show called The Possession. A film documents the family and especially Marjorie, the one who claims to have the ghosts in her head.

As the novel builds towards an exorcism event, Tremblay plays with opposites (e.g. cold and hot, fiction and nonfiction) to suspend the uncertainty. Father Waverly, the aptly named priest involved with the family, talks about the financial gain coming from the TV show. And fourteen-year-old Marjorie seems to enjoy the limelight. Perhaps this is all a moneymaking and/or an attention-getting scheme. But then again, how is Marjorie accessing the knowledge that she confidently spews at the priest? What are these strange things happening in her room? She could just be a precocious kid, or maybe there’s something else going on.

Tremblay also flips around in time and narrative format. While much of the story plays out through the perspective of eight-year-old Merry, the novel also contains passages in which a woman planning to write a tell-all book interviews a twenty-three-year-old Merry to get her side of what happened on the show. Additionally, excerpts from The Final Last Girl blog reinforce the ambiguity of the situation. Blogger Karen Brissette, writing fifteen years after the show, rips it apart, commenting on its amateur cast, lewd imagery and clichés. She references everything from The Exorcist and Lolita to more recent works like The Ring and a “lukewarm parade of possession movies” from the 2000s. The blog is most interesting when its chatty author breaks down scenes from the show. Some readers might not like getting pulled out of the story for this deconstruction. I happened to enjoy it.

Beyond a possession novel, A Head Full of Ghosts comments on contemporary media and art and their ability to manipulate actors and yes, even readers and viewers. Typically, revisiting worn-out horror tropes would be anathema to good storytelling, but in Tremblay’s hands, everything you’ve come to expect moves in a new direction. Douglas J. Ogurek ****

August 16, 2025

Millionaires Day by Kit Power (French Press Publishing) | review by Stephen Theaker

We cannot be sure if the phenomenon extends beyond Milton Keynes – there is a news blackout – but it seems that everyone in that city who was asleep at 8.04 am on 22 December 2019 woke up with a suitcase containing a million pounds beneath them. You might wonder why, but this novella isn’t very interested in that. Instead, it concerns itself with how various ne’er-do-wells try to get their hands on other people’s suitcases, and how those others try to escape them.

We cannot be sure if the phenomenon extends beyond Milton Keynes – there is a news blackout – but it seems that everyone in that city who was asleep at 8.04 am on 22 December 2019 woke up with a suitcase containing a million pounds beneath them. You might wonder why, but this novella isn’t very interested in that. Instead, it concerns itself with how various ne’er-do-wells try to get their hands on other people’s suitcases, and how those others try to escape them.At first we follow three main characters, each of whom hands us off at various points to other people. Henry is a homeless man sleeping in an underpass. He tries to get a first class train to Glasgow but is spotted by police officer Luke, who has been falling out of love with his husband for a while now, ever since their attempt to use a woman as a surrogate fell through. The mother kept her daughter, and the court hasn’t ordered contact despite Luke being the biological father.

Emma is a neglected nine-year-old girl, forced to sleep in a car when mum has a guest over. When she finds the money, her imaginary friend Rachel, an emancipated child from a tv show, encourages her to walk to a toy shop. Emma picks out some nice toys but on the way to the till is stopped by Keith, a sadistic security guard who wants her money and will enjoy hurting her to get it. Ignoring Rachel’s advice, she gets in his van.

Pete Harding works for a particularly nasty criminal, Mickey, who runs their tower block with an iron fist and no velvet glove. On suitcase morning, Pete wakes up to find himself in bed with Mickey’s sister. His attempts to get out run afoul of Mickey’s plan to get every suitcase in the tower block into his own hands. For me this was the most memorable aspect of the book: a gang of criminals breaking into dozens of homes, utterly unafraid of the consequences.

I bought Millionaires Day (the absence of an apostrophe is correct) because it was nominated for best novella in the British Fantasy Awards 2025. Although I was only its fourteenth reader on Goodreads, it’s easy to see why it was nominated: though I love the BFAs dearly, they do have a tendency to be local awards for local people, and the author is a popular chap, writing for Ginger Nuts of Horror, which gets nominated for best magazine/periodical in the same awards almost every year despite being neither a magazine nor a periodical.

But for me there wasn’t much to get excited about here. The writing is okay, and the villains are nasty enough to give the book some appeal to horror fans. But for a fantasy fan there was little of interest. The suitcases’ origins are never explored or explained, so for all we know nothing fantastical happened in the book at all, other than an unusually thick mist and a couple of odd sections later on suggesting (again without explanation) that the imaginary friend might be real.

There is nobody in the story who puts their foot on the ball and tries to think it through. Compare it to The Measure by Nikki Erlick, which has a similar premise – everyone over a certain age receives a piece of string in a box – but explores it thoroughly and methodically. In contrast, this book covers just the first few hours after the event. The real-time progression of the story is well orchestrated, but we see nothing but the street-level response.

Seeing events from various points of view produces some good moments, but often feels quite artificial, for example the overly mechanistic sections from a dog’s point of view, or when we meet Billy, a key member of Mickey’s gang. Narrative withholding can be a useful device, but after seeing Billy from three different points of view it starts to seem unlikely that none of them mentions whether Billy is male or female.

For me, it’s a book that wastes an promising premise on a gangster runaround. How would randomly giving lots of people a million pounds change society? Would the money retain its value or would such a huge influx of cash lead to a devaluation of the pound? Was the money taken from somewhere or was it magically created? You won’t find out from this book – though, to be fair, given that this is just a novella (albeit quite a long one) perhaps such questions were deliberately set aside for a sequel. **

August 8, 2025

The God of Wanking by Peter Caffrey | review by Stephen Theaker

In August 2024 I attended a free one-day convention organised by Indie Horror Chapter in Birmingham, a gathering of self-published authors getting together to sell books, do readings and make friends. One of the most eye-catching tables was that of Peter Caffrey, whose books stood out thanks to their bright colours, striking designs and memorable titles. Here was an author clearly doing his own thing, not trying to mimic mainstream horror, carving out a very specific niche. You probably won’t see Whores Versus Sex Robots and Other Sordid Tales of Erotic Automatons on sale in Waterstones.

In August 2024 I attended a free one-day convention organised by Indie Horror Chapter in Birmingham, a gathering of self-published authors getting together to sell books, do readings and make friends. One of the most eye-catching tables was that of Peter Caffrey, whose books stood out thanks to their bright colours, striking designs and memorable titles. Here was an author clearly doing his own thing, not trying to mimic mainstream horror, carving out a very specific niche. You probably won’t see Whores Versus Sex Robots and Other Sordid Tales of Erotic Automatons on sale in Waterstones.The God of Wanking – and titles don’t come much more attention-grabbing than that! – is a short novel first published in 2021. Our protagonist is Diego, who attends a strict catholic school in a village that would seem to be in Central or South America. It wasn’t clear which, but the power of the Catholic church there appears to be totally unbridled – we see them snatching people off the street. When the book takes place was also unclear, but the villagers have televisions and don’t have mobile phones, which gives some idea.

The sadistic priests at the school regularly cane the children, pants off, and Diego will take his turn, but the book begins with him in a happier place, dreaming of a sexy woman. He wakes in a state of incomplete passion, let us say, and struggles to sort himself out with Jesus watching from his crucifix on the bedroom wall. So he heads to the living room, but there's Jesus again. Fearing himself at risk of testicular explosion, Diego goes outside, to an abandoned shrine. He does the deed there, and in his enthusiasm splashes an effigy made of corn.

Diego thinks of this figure as the God of Wanking, but upon awakening from its decades-long slumber it tells him its preferred name: the Fornicator. This being, god, demon, monster, whatever, takes control first of his libido, and then of his life, and its ambitions don’t stop there. His schoolfriend Maria tries to help, but their mutual affection only strengthens the Fornicator’s hand, giving it another way to put pressure on the boy. When the Church takes a violent interest in subsequent events, Diego and the villagers are screwed backwards and forwards, in more ways than one.

I was expecting this to be a very different kind of book, one that was shocking for shock’s sake, and while there is a lot of extremely unpleasant sexual violence, torture and cruelty, that often happens to vulnerable people – children, women, the elderly – the shocks serve the story, rather than the reverse. None of it is as gruelling as it might be in a book with a more serious, realistic tone. Not knowing exactly when or where these events happen contributes to it feeling like a fable or a fairy tale, as if Stephen King were set loose on the Palomar stories of Gilbert Hernandez. I liked it. ***