Stephen Theaker's Blog, page 6

December 3, 2024

M3GAN | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Screen time leads to scream time: AI gone haywire tale zeroes in on impact of technological surrogacy on child development.

Screen time leads to scream time: AI gone haywire tale zeroes in on impact of technological surrogacy on child development.A common restaurant scenario: Mom and Dad look at their phones while Timmy or Sally stares at an iPad. The problem of technology encumbering the parent-child dynamic continues to worsen. M3GAN, directed by Gerard Johnstone, reveals how artificial intelligence might compound the difficulty. The film not only explores the potentially catastrophic effects of substituting technology for human interactions but also investigates how AI might stifle the grieving process.

When Cady’s (Violet McGraw) parents are killed, she moves in with her hitherto child-free (and parentally inept) Aunt Gemma (Allison Williams), a development whiz at a high-tech toy company called Funki. Motivated by her new ward, Gemma overcomes some hiccups to develop the Model 3 Generative Android, or M3GAN (Amie Donald/Jenna Davis), a prototype AI doll that her boss calls the biggest invention since the automobile. The doll is programmed to learn from Cady, educate her, and above all, keep her safe. Gemma, assuming she’s now free of her guardianship duties, hands the doll to Cady and figuratively claps her hands. There. You two go play while I work.

Two problems emerge. First, M3GAN begins to bend and eventually break rules to meet her primary goal of protecting Cady. That’s the expected part. The more interesting matter, however, is the impact M3GAN has on how Cady mourns the loss of both parents. When something like M3GAN imprints on a grieving child, warns a psychologist, that can be a difficult thing to “untangle”.

In one poignant scene, Cady explains to Gemma that M3GAN helps her avoid feeling bad about the loss of her parents. Gemma, showing insight that is arguably out of character, explains that Cady is supposed to be having bad feelings. And she’s right.

The film also succeeds on the horror front. M3GAN, with her abnormally large eyes and superhuman physical abilities, keeps the viewer on edge. When Gemma commands the doll to turn off, one cannot be sure the figure is obeying. Moreover, the viewer occasionally gets to see from the doll’s perspective: a digital screen reminiscent of the Terminator’s gauges humans’ emotional states and bodily reactions. M3GAN uses these measurements to make her decisions.

Despite its silly ending, the film is still highly recommended — and it might make you more reluctant to throw an iPad in front of your kid the next time the temptation arises. Douglas J. Ogurek ****

November 29, 2024

The Girl from the Sea, by Jessica Rydill (Midford Books) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review was originally published in December 2019 on an earlier iteration of the British Fantasy Society's website, and then appeared in TQF67 (July 2020).

This review was originally published in December 2019 on an earlier iteration of the British Fantasy Society's website, and then appeared in TQF67 (July 2020).Aude d’Iforas, swimming naked in the ocean, encounters Yuste and Yuda, twins with psychic powers, destined to be shamans. Their family are Wanderers, supposedly cursed for the crimes of their ancestors. Her own family of Doxan northerners has been banished, far from their home, after a spell she cast went badly wrong. The three teenagers make friends and the twins tell her of a drowned city that lies beneath the waves, called Savorin. Before they know it, a hooded figure with a face of white bone and hollow eyes has risen from the depths and rides a glistening boat towards them, accompanied by a dangerous storm.

The setting for this novella seems to be a low-technology future, as characters are aware of our medieval past, but talk about the centuries of the Great Cold, ride in steam coaches and airships, and are aware of electric lighting and plans to build new railways. They sometimes use German and French words, but currently live in an area, Lefranu, where people speak a language called Franj. Anti-semitism, sexism and racism are still serious problems. For shamans among the Wanderers, gender is said to be fluid, but their women are still expected to seclude themselves during their periods and boys still face circumcision.It is a prequel to the novels Children of the Shamen and The Glass Mountain (published by Orbit in 2001 and 2002), but there are no barriers to readers new to the series. It uses rather too many semi-colons, sometimes incorrectly in place of commas, but more often in places where a full stop would just be easier on the reader. A second problem is that, after an exciting beginning, we’re two thirds of the way in before anything else really happens. But it ends well, with an exceedingly creepy confrontation, and does feel like a complete story in itself, which is more than can be said for many fantasy and science fiction novels at the moment. It’s currently [December 2019] available on Kindle Unlimited, as well as to buy in ebook and print. Stephen Theaker ***

November 22, 2024

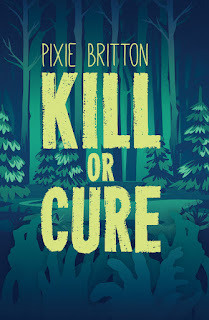

Kill or Cure, by Pixie Britton (Matador) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review was originally written for the previous British Fantasy Society website, and then appeared in TQF65 (December 2019).

This review was originally written for the previous British Fantasy Society website, and then appeared in TQF65 (December 2019).The first few chapters of this zombie YA novel are quite run-of-the-mill. Alyx, a seventeen-year-old girl, is desperate to help her poorly younger brother. Back in 2042 or so their parents were eaten by zombies – the Infected – which have successfully taken over the world, leaving humans eking out life in small villages, at risk of being overrun. Alyx has sneaked into the woods to look for medicine. It all feels overfamiliar, as if at every step the decision was made to follow the most obvious route. Then, after his infection is discovered and they are forced to run for their lives, and just when Alyx is ready to send her brother up the stairs to metaphorical Bedfordshire one last time, something unexpected happens. The boy doesn’t turn into a zombie, he morphs...

That was definitely a surprise. Unfortunately, it doesn’t herald an improvement in the book. It reads like a Nanowrimo first draft, full of conventional phrasing, first-thought-in-your-head plotting, and clumsy writing (“A cold shiver trickles down my spine, which instantly makes me shudder in response”) – perhaps because it was originally self-published episodically on Wattpad. The characters riffle, rifle and rummage through their backpacks so often that you wish they would just sit down and organise them properly. At one point Alyx realises she has a broken rib, but hasn’t been bitten, and says, “I have never been so pleased to crack a rib in my life”, as if that’s an everyday occurrence.It feels as if the characters have got stuck in an early part of the novel plan, since most of the book is spent in the first opposition they encounter upon leaving their village: the bulk of it is about Alyx’s attempt to rescue their uncle from soldiers who have arrested him for desertion. The book ends when they get away, but nothing is resolved, we’ve found out very little about the boy’s morphing ability, and it feels like the story stops there for no other reason than that’s where the book ends.

It’s all so shallow. A man sexually assaults Alyx, and then the book has her immediately snogging, outdoors, in her underwear, another guy who comes to help. She shoots someone, leaves him bleeding and locked up in a storage container (justifiably so), and no one ever mentions it again. And while it’s written in the first person, it’s hard to empathise with her when she’s so irresponsible, sneaking someone she knows is to some extent infected into a human colony, or pressing a gun against the forehead of an ally because they won’t answer a question. She lets herself be convinced very easily by her best friend Will that it doesn’t matter if innocent soldiers die during their escape (“I would rather die trying with even the smallest hope that we have the cure than to save a few soldiers who are willing to die for the same cause anyway”) – especially shocking when you consider that she and Will and her brother are not prisoners and could leave at any time.

On the plus side, the chapters are short, making it a convenient book for reading in short bursts, the chapters usually end at a dramatic point, and there is unintentional humour from the inappropriate grinning and chirpiness (“I’m fresh outta ideas!”) but this isn’t a book I would recommend. Stephen Theaker **

November 19, 2024

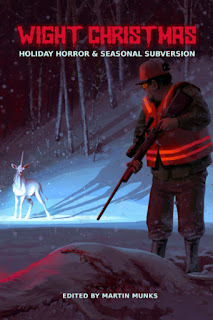

Wight Christmas: Holiday Horror & Seasonal Subversion, ed. Martin Munks (TDotSpec) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

A solid collection of horror stories to ring in the Christmas season.

A solid collection of horror stories to ring in the Christmas season.A winter slaughter mars a Kentucky swampland. A murder unfolds at Santa’s workshop. Methamphetamines benefit mankind. This anthology, with stories ranging from silly yet entertaining to grim and frightening, offers many manifestations of the figure in red. One is scaly and crude, some are vicious murderers, one is connected to an ancient deity, and some enjoy burning corpses. One even hitches rides on spaceships.

A few stories seem solely spurred on by their surprise ending; everything that builds up to that ending seems weak. Others suffer from an avalanche of details, while a few are as clear as the slush that accumulates on city streets in winter. Some authors appear to be inspired by Lifetime movies, and some try too hard to sound like a writer. Using onomatopoeia to describe the sounds of bells? Dinga-linga-dumb.

Fortunately, there are only a few coal lumps in the anthology. Overall, it makes a great stocking stuffer… provided the recipient likes horror. Most of the stories entertain and several achieve excellence. Editor Martin Munks places the stories in a sensible order, and unlike many horror anthologies, this one has few mistakes. Following are some of my favourites.

Jude Reid’s “(Everybody’s Waitin’ for) the Man with the Bag” has everything one would want in a horror story: plot twists, people getting their comeuppance, a decorative flair for blood and guts, and much more.

“All Alone on Christmas” by Chris Campeau stands out as a sanctification of loneliness. A divorced man staying in a chalet and missing his son encounters an ugly, frostbitten, pus-ridden, naked bearded figure (a possible personification of loneliness), but it’s hard to tell whether this somewhat familiar visitor has a malicious intent or would rather just chill. The story comments on the often conflicting values of work and family.

David F. Shultz’s “The Santas” is inventive, funny and, at times, sad. After a botched suicide attempt, a man gets a crass visitor with an unexpected gift. Shultz smatters the story with just enough detail to create an atmosphere. We discover that Santa Claus is just one of many Santas, each of which has a different appearance. The only thing I didn’t like about this story was facing the fact it had to end.

In “A Christmas Cake” by Kara Race-Moore, the narrator goes all out to bake a traditional Irish christmas cake for her tactless boyfriend, who abruptly breaks up with her and shatters her view of the relationship. He refers to her as “Christmas cake” – an old-fashioned Japanese term for a single woman over 25 – and accuses her of being desperate to get married and have babies. A meeting with a familiar elderly woman leads to a surprise ending that leaves a few loose threads.

Olin Wish’s “Have a Holly, Jolly Nuclear Winter”, one of the collection’s scariest stories, involves a husband and a wife doing something involving physics, drugs and mirrors. It has a voyeuristic tone, with the bulk of the activity involving them standing at a window. They attempt to avoid drawing attention to themselves as they witness a halcyon European scene transform into a ghastly activity.

“The Naughtiest” by John Lance is part Christmas cartoon and part cozy mystery. Santa’s elves investigate a murder and kidnapping at the workshop. We learn what’s in Mrs Claus’s kitchen and even get to explore the mines Santa used for coal before he closed them down because of health concerns. The protagonist is Bobkin, an elf with a strong focus on following the rules. It’s a cute story – there’s even a plunger detonator bomb. The story shows how if a child is continually punished and never rewarded, that behaviour may result in long-term problems.

In Shelly Lyons’s “Ho-Ho-Nooo!”, main character Tony Flores is a meth addict with a gig as a Santa at a Spencer’s Gifts store in the ’90s. Because of something that happened with a ship that crashed, he is determined to save his friend and fellow Santa Mike Cheebers, working at the Sears in the same mall. It’s humorous, it’s light, and it’s nostalgic. Douglas J. Ogurek ****

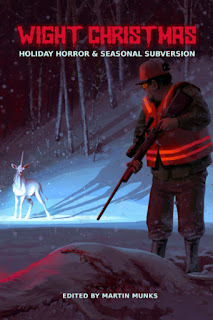

Wight Christmas: Holiday Horror and Seasonal Subversion, ed. Martin Munks (TDotSpec) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

A solid collection of horror stories to ring in the Christmas season.

A solid collection of horror stories to ring in the Christmas season.A winter slaughter mars a Kentucky swampland. A murder unfolds at Santa’s workshop. Methamphetamines benefit mankind. This anthology, with stories ranging from silly yet entertaining to grim and frightening, offers many manifestations of the figure in red. One is scaly and crude, some are vicious murderers, one is connected to an ancient deity, and some enjoy burning corpses. One even hitches rides on spaceships.

A few stories seem solely spurred on by their surprise ending; everything that builds up to that ending seems weak. Others suffer from an avalanche of details, while a few are as clear as the slush that accumulates on city streets in winter. Some authors appear to be inspired by Lifetime movies, and some try too hard to sound like a writer. Using onomatopoeia to describe the sounds of bells? Dinga-linga-dumb.

Fortunately, there are only a few coal lumps in the anthology. Overall, it makes a great stocking stuffer… provided the recipient likes horror. Most of the stories entertain and several achieve excellence. Editor Martin Munks places the stories in a sensible order, and unlike many horror anthologies, this one has few mistakes. Following are some of my favourites.

Jude Reid’s “(Everybody’s Waitin’ for) the Man with the Bag” has everything one would want in a horror story: plot twists, people getting their comeuppance, a decorative flair for blood and guts, and much more.

“All Alone on Christmas” by Chris Campeau stands out as a sanctification of loneliness. A divorced man staying in a chalet and missing his son encounters an ugly, frostbitten, pus-ridden, naked bearded figure (a possible personification of loneliness), but it’s hard to tell whether this somewhat familiar visitor has a malicious intent or would rather just chill. The story comments on the often conflicting values of work and family.

David F. Shultz’s “The Santas” is inventive, funny and, at times, sad. After a botched suicide attempt, a man gets a crass visitor with an unexpected gift. Shultz smatters the story with just enough detail to create an atmosphere. We discover that Santa Claus is just one of many Santas, each of which has a different appearance. The only thing I didn’t like about this story was facing the fact it had to end.

In “A Christmas Cake” by Kara Race-Moore, the narrator goes all out to bake a traditional Irish christmas cake for her tactless boyfriend, who abruptly breaks up with her and shatters her view of the relationship. He refers to her as “Christmas cake” – an old-fashioned Japanese term for a single woman over 25 – and accuses her of being desperate to get married and have babies. A meeting with a familiar elderly woman leads to a surprise ending that leaves a few loose threads.

Olin Wish’s “Have a Holly, Jolly Nuclear Winter”, one of the collection’s scariest stories, involves a husband and a wife doing something involving physics, drugs and mirrors. It has a voyeuristic tone, with the bulk of the activity involving them standing at a window. They attempt to avoid drawing attention to themselves as they witness a halcyon European scene transform into a ghastly activity.

“The Naughtiest” by John Lance is part Christmas cartoon and part cozy mystery. Santa’s elves investigate a murder and kidnapping at the workshop. We learn what’s in Mrs Claus’s kitchen and even get to explore the mines Santa used for coal before he closed them down because of health concerns. The protagonist is Bobkin, an elf with a strong focus on following the rules. It’s a cute story – there’s even a plunger detonator bomb. The story shows how if a child is continually punished and never rewarded, that behaviour may result in long-term problems.

In Shelly Lyons’s “Ho-Ho-Nooo!”, main character Tony Flores is a meth addict with a gig as a Santa at a Spencer’s Gifts store in the ’90s. Because of something that happened with a ship that crashed, he is determined to save his friend and fellow Santa Mike Cheebers, working at the Sears in the same mall. It’s humorous, it’s light, and it’s nostalgic. Douglas J. Ogurek ****

November 15, 2024

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin (The Folio Society) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review was written in 2020 for the British Fantasy Society's previous website.

This review was written in 2020 for the British Fantasy Society's previous website.This reads at first like old-school adventure sf, beginning with a sequence on a spaceship launchpad that could have come straight from a Dumarest novel. Sadly, that is no indication of where the book is heading. It is set several hundred years in the future. The Cetians (as humans have labelled the people of the two worlds, and as they have begun to call themselves) know of Earth but we are aliens to them. We have an ambassador on Urras, but no contact at all with the isolated colony founded on its moon, Anarres, two hundred years ago.

The book concerns a humourless physicist, Shevek, who grew up on Anarres, but travels to Urras. His society is based on communal, anarchist principles. Resources are scarce and egoising is considered a grave sin. Shevek has been exchanging letters and ideas with the physicists of Urras, and realises that some of the greatest physicists of his own world are mere plagiarists of their work. He is encouraged to visit, and he does, riding a trade ship. Urras, it turns out, is quite a bit like our world in the twentieth century, with Shevek staying in a capitalist and sexist country reminiscent of the USA of the 1950s.Lengthy chapters alternate between rather tedious explorations of Shevek’s past and present. On the moon we see his growing discontent and frustration, not with its anarchist politics as such, but with the ways in which anarchism has hardened into unacknowledged governance and control, and how that blocks his scientific progress, and the progress of others, such as a composer who spends his life building canals because not enough people approve of his music. On the planet Urras he sees continued evidence of the problems his people fled from, but also a freedom of ideas that surprises him.

The Dispossessed is regarded by many as a classic of the genre, but I found it very hard going, as evidenced by the fact it took me one hundred and seventeen days to finish it. I thought maybe it was the bulkiness of this Folio edition slowing me down – this chunky hardback is for when you’ve got an evening lined up in an armchair, not for bus stops and waiting rooms – but it was just as slow going with the more portable Library of America and SF Masterworks editions. Curiously, once I admitted to myself that I found it boring, and stopped trying to enjoy it, I had it finished within a week.

Like some other books of the era, it has a rather dodgy attitude to children and sexuality: “No law, no limit, no penalty, no disapproval applied to any sexual practice of any kind, except the rape of a child or woman”, we are told. In practice we see that this means children having sex with each other, and adults having sex with children, and it all feels uncomfortably similar to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s defence of her husband: propositioning children wasn’t a problem as long as he took no for an answer. When Shevek tries to rape a woman on Urras, he suffers no consequences, but the unfortunate reader has to spend another hundred pages with him.

So this isn’t a book I liked or enjoyed, but I suspect that the target audience for this edition are those who already know and love the novel. As you would expect from the Folio Society, it is a very nice edition. They describe it as bound in printed and blocked cloth, with printed map endpapers, a printed slipcase and 14 integrated illustrations (eight in duotone, six in greyscale) by David Lupton, who also worked on their editions of A Wizard of Earthsea and The Left Hand of Darkness. Bleak and sombre, they reflect the mood of the book very well. Professor Brian Attebery, who worked with Le Guin and edited two volumes of Hainish Novels & Stories for the Library of America, provides an introduction, which should definitely be read after the novel. Stephen Theaker ***

The book can be purchased here: https://www.foliosociety.com/the-dispossessed.html

November 8, 2024

Agents of Shield, Season 5 | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019). Daisy Johnson did not go on to appear in Avengers 4, unfortunately.

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019). Daisy Johnson did not go on to appear in Avengers 4, unfortunately.Agents of Shield has always been a decent, dependable show, rather than a knockout. Like Flash, Arrow and Legends of Tomorrow, we tend to catch up with it during the summer. But it has improved steadily, and looking back through online wikis about the characters, it’s striking how much they’ve been through, how many adventures they’ve had, and how much I enjoyed them. The division of seasons four and five into mini-seasons has re-energised the show. In season four the team met Ghost Rider, dealt with life model decoys and got stuck inside a virtual bubble universe, while in this season they are stranded in a desperate future timeline, and then try to prevent it happening in the present. (The latter storyline takes place contemporaneously with Thanos and his goon squad duking it out with the Avengers.) Regularly changing the premise of the show keeps the show feeling fresh. The main cast – playing Coulson, May, Daisy, Mac, Yoyo, Fitz and Simmons – are by this point very comfortable in their roles, and this season, originally thought to be its last, pays off our investment in those relationships. There are also references back to the previous four seasons throughout, tying the whole saga up in a bow. If this had been the end, it would have been a good one. But it’s been renewed, and though it’ll be a long, long wait till season six in the summer of 2019, it’ll be great to see Coulson back on the big screen in Captain Marvel, and I have my fingers crossed for Daisy Johnson in Avengers 4. Though it’s still not the fully-fledged Marvel Universe programme everyone was hoping for when it was first announced, it does its best. And though it’s still not a show I need to watch at the earliest possible opportunity, that’s only because the competition is so strong these days. The special effects are spectacular, the jokes are funny, the villains are hissable, and the stakes are high. Plus there’s Deke, who seems at first like a stand-in for Starlord and ends up being the breakout star of the season. I like Deke. Stephen Theaker ***

November 1, 2024

BFS Journal #18, edited by Allen Stroud (The British Fantasy Society) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).

This review originally appeared in TQF64 (March 2019).The eighteenth issue of the BFS Journal continues its laudable attempt to turn into an academic journal, a process that began when the current editor took over. Unfortunately this issue doesn’t seem to have been copy edited or proofread, which undercuts the lofty aims.

Redundant apostrophes (“the doom of their kingdom’s”), commas in odd places (“author Michael Moorcock, calls”), words missing, full stops used randomly in the references. Some author names and titles appear in all caps, others in title case. A quote ends with “emphasis in original” even though there’s no emphasis. Random formats for sub-headings. The titles of books referenced aren’t consistently italicised, and there are so many unpaired parethentical commas one could write an entire novel with the leftovers. One author likes to “peak behind the curtain of reality”, another is “wiling” away his time, etc. It’s a mess, basically.

The academic articles use the sensible and efficient author–date system, but its usefulness is hampered here by the years appearing at the end of the references, rather than straight after the authors’ names, as is usual, and multiple books by a single author are not always arranged by publication date. Looking up references is also slowed down by them sometimes being divided by type, meaning the reader must check one list for the author’s name, then the next. The references would also benefit from the use of a hanging ident, as is standard elsewhere, so that the authors’ names would stand out. Other references don’t lead anywhere at all (like Scholes, 1975, and Grove, 1879, in the article on Olaf Stapledon).

The articles are a mixed bag. David Sutton’s article about the history of the British Fantasy Society was extremely interesting the first time I read it, in the BFS booklet Silver Rhapsody, but serialising an old article over three issues of the Journal seems odd, especially when it’s already available on the society’s website. Hopefully the series will continue past 1984, where the original article ended. Two articles by Allen Ashley about the summer SF exhibitions are good, though like me he doesn’t seem to have been too impressed.

The more academic essays can make interesting points, but it is a bit like reading someone else’s university essays, and as evidenced by the letter from a long-time member that appears in the journal, they do not always show the deepest understanding of the fantasy genre. Or the world, in some cases – it seems a stretch to say that the world wars of the twentieth century have “snowballed” into the present day, as Shushu Li suggests. The same article’s bibliography suggests that Pelican Books, founded in 1937, published a book in 1905, which is quite a feat.

Another article’s title is “‘You Know Nothing Jon Snow’: Locating the Feminine Voice of Maturity, Motherhood and Marriage in 21st Century Fantasy Fiction”, and yet it talks exclusively about A Game of Thrones, published in 1996. (A publication date of 2011 is given. The journal would benefit throughout from the use of square brackets to indicate the original publication date of a book’s publication.) The same article manages to spell M. Lipshitz’s surname correctly and incorrectly in the same sentence. And it doesn’t mention Jon Snow or Ygritte once: the quote is from A Storm of Swords, not discussed in the article. Similarly, a fairly interesting article is called “Music in the Science Fiction Novels by Olaf Stapledon”, despite being entirely about one book, Sirius.

If the BFS Journal wants to be an academic publication, it has to be more rigorous than this, for the sake of its contributors as much as the society members who pay for it. If it’s peer-reviewed, the peers need to do their job properly. It needs to be copy edited and proofread. As a fan publication, the BFS Journal is admirably ambitious (and the return of issue numbers to the cover is very welcome), but as an academic publication it needs much more work. Stephen Theaker **

October 30, 2024

#OcTBRChallenge 2024: a fourth and final A to Z of books and audiobooks

I took part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I tried to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I could, in A to Z order. It's been highly enjoyable. My first A to Z of the month is here, the second is here, and the third is here. I didn't think I was going to manage a fourth A to Z by the end of the month, but I threw out the ballast, trimmed my sails, swapped some short books out for even shorter books, and got there with a day to spare!

I took part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I tried to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I could, in A to Z order. It's been highly enjoyable. My first A to Z of the month is here, the second is here, and the third is here. I didn't think I was going to manage a fourth A to Z by the end of the month, but I threw out the ballast, trimmed my sails, swapped some short books out for even shorter books, and got there with a day to spare!The fourth A of the month is for Am I Actually the Strongest, Vol. 1, by Sai Sumimori and Ai Takahashi, about a layabout reborn as a baby in a fantasy world with what is assumed to be a rubbish power. But he finds imaginative ways to use it and his mana is exceptionally high.

B is for The Black Moon Chronicles, Vol. 5: The Scarlet Dance, written by François Froideval, with poster-style art by Olivier Ledroit that's more illustrative than sequential. I haven't got into this series yet. It's like someone's shouting the story at you while they run past.

C is for Cosmoknights by Hannah Templer, a future sports comic about a girl who runs away from home, after previously helping a princess run away too. She teams up with a pair of lesbian princess rescuers, but there's a male on their trail, trying to coerce a way into their gang.

D is for Dark Spaces: Wildfire by Scott Snyder and Hayden Sherman, about a group of female prisoners on day release to fight forest fires. Told that a house in the fire's path contains a fortune in cryptocurrency, they risk everything to sneak in there and get it before it burns.

E is for The Egyptian Princesses, Part I, a black-and-white graphic novel by a Ukrainian writer and artist, Igor Baranko. Circa 1150 BC, two young daughters of the pharaoh Ramesses III are led into a deadly trap, but survive it to discover magic, mysteries and weird old men in the desert.

F is for Flywires, Vol. 3: Organic Transfer, by Chuck Austen and Matt Cossin. Illegal reproduction has run rife on a generation ship and drastic measures are now required to keep life support running. Feels like the creators were told to quickly wrap it up, but at least it got an ending.

G is for Gleipnir, Vol. 1, by Sun Takeda, about a sad boy, Shuichi Kagaya, who turns into a sports mascot costume when agitated, and the weird girl who realises she can unzip the costume, climb inside it, and use its strength to kill people. It's all very saucy and symbolic.

H is for The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien, the brilliant fourth Maigret novel by Georges Simenon, translated by Linda Coverdale and read by Gareth Armstrong. The maudlin Maigret follows a shady character all the way to the German border, only to provoke his suicide at the train station. It leaves the great detective decidedly out of sorts.

I is for It Waits in the Woods by Josh Malerman, another short ebook that's free to read in Prime Reading. A scary movie just dying to be made, it's about an 18-year-old film-maker who goes into Central Michigan's National Forest with a camera to find her sister, who went missing three years ago.

I'd been picking at Les Justes by Albert Camus all month but time was running out so J was instead for Jack Wolfgang, Vol. 1: Enter the Wolf, by Stephen Desberg and Henri Reculé. It's a fun James Bond adventure in a world where animals have learnt to walk, talk and come up with megalomaniacal schemes.

K is for Kaya, Vol. 1: Kaya and the Lizard-Riders, by writer and artist Wes Craig. A tough girl tries to get her princeling half-brother to safety among her crush's lizard-people, after robot invaders torch their home. Lovely artwork in nice, rectangular, digital-friendly panels.

L is for Legend of the Scarlet Blades, Vol. 4: The Abomination's Hidden Flower, by Saverio Tenuta, translated by Samantha Demers. Glorious artwork and an epic story. For the full effect I think it would be better to read all four books at once rather than over the course of three years.

M is for Miao Dao, a horror story by Joyce Carol Oates about Mia, a 13-year-old girl being sexually harassed at school by older boys, and at home by a stepdad. She befriends some feral cats, and one becomes her protector. Read by Amy Landon, who does a great "creepy man" voice!

N is for November, Vol. 2: The Gun in the Puddle, by Matt Fraction and Elsa Charretier. I didn't feel that this moved the story forward a great deal from volume one, but maybe the problem is that I whizzed through it too quickly rather than soaking up the mood and the artwork.

O is for The Owl, by J.T. Krul, art by Heubert Khan Michael, a spin-off from Project Super-Powers, where Alex Ross and his team gave public domain characters the care and attention usually reserved for Marvel and DC heroes. I read this out of order (a late substitution for an audiobook I wasn't close to finishing) so it was my 100th book of the month!

P is for Public Domain, Vol. 1: Past Mistakes by Chip Zdarsky. I adored this. A Jack Kirby/Steve Ditko/Bill Finger realises he owns a major superhero, not the writer and his company. What really made it for me was the big left-turn it takes after the lawyers talk.

Q is for The Queen in Hell Close by Sue Townsend, a comic Penguin 70 about a new government kicking the royal family out, and making them sign on. A brilliant portrayal of what it's like to live without money, but also rather a nice tribute to the Queen. I read it on the bus, and it was the first book I ever read with my reading glasses on. It does have very small print, to be fair!

R is for Rage, written by Jimmy Palmiotti, with art by Scott Hampton and Jennifer Lange. A chap gets thrown in prison after his ex pretends he kidnapped their daughter. Knocked out by another prisoner, he wakes up to see that everyone else in the cell has been beaten to death…

S is for Second Best Thing: Marilyn, JFK, and a Night to Remember, by James Swanson, a short ebook about the one and only photograph of Marilyn Monroe and JKF together, on the night of his birthday fundraising event, and the private party (or two?) that followed. The kind of thing I would never normally have read, but reading challenges can sometimes prod you in odd directions.

T is for Throne of Ice, Vol. 1: Orphan of Antarcia, by Alain Paris with art by Val, translated by Lindsay Marie King. A fantasy story set circa 8000 BC on Antarctica, when humans supposedly still lived there, before it froze, and a vicious queen wanted her king's illegitimate son dead, while one wiley retainer stops at nothing to keep him alive.

U is for The Unwritten, Vol. 1: Tommy Taylor and the Bogus Identity, by Mike Carey and Peter Gross. Tom is famous for the Harry Potter-ish novels his long-lost dad wrote him into, but then a journalist reveals he may not be his dad's actual son, setting some wild events in motion. Pretty cool.

I'd hoped that The Veiled Woman, a Penguin mini by Anais Nin,would be the V this time around, because I'd already read quite a bit of it this month, but sadly the light in the pub in which I was waiting for my daughter was too dim for a print book with a tiny font. Never mind, maybe next year! So V was instead for Void by Veronica Roth. While Ace works as a janitor on a interstellar cruise ship, time passes quickly (or normally) elsewhere, so today's baby could be next year's elderly man – it's The Forever War as service industry. When a favourite passenger is murdered, Ace can't help investigating.

Similarly, I'd hoped that Witching Hour Theatre by Jonathan Janz would be the W, but I wouldn't have finished it in time. It's very good so far, though. It's about a lonely chap who spends every Friday at an all-night horror movie triple bill with other aficionados. Instead, W is for Wings of Light, Vol. 1, by Harry Bozino, with art by Carlos Magno, based on an original story by Julia Verlanger. A former Retroworld slave becomes a cadet in the Brotherhood of the Stars, and on his first assignment rescues a pregnant woman from the axe, causing a diplomatic incident.

X is for XO Manowar, Vol. 1: Soldier by Matt Kindt, with fabulous art by Tomas Giorello. I picked this out because my other remaining X books were lengthy omnibuses of X-Men comics and the Xeelee Sequence (estimated reading time: 45 hours!), but it was an unexpected treat. A roman soldier, who got some space armour and then retired to an alien planet after his adventures on present-day Earth, gets dragged off to war again.

Y is for Young Hellboy: The Hidden Land, written by Mike Mignola and Thomas Sniegoski, with art by Craig Rousseau. Little red and Professor Bruttenholm are stranded on a lost island, where they meet another of Hellboy's idols. Aimed at kids, I think, but it was good fun.

And last but not least, my final Z is for Zenith: Phase Four, by Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell, another mind-boggling attempt to reprogram your consciousness via superheroes and pop stars. I've got 78 other 2000 AD books I haven't read yet – I should do something about that. Together with Zenith: Phase Four and Nameless, that takes Morrison to the top of my leaderboard for I think the first time ever, at 67 books read, ahead now of Garth Ennis (66), Moorcock (62), who I think lost the lead in 2022 or so, and Terrance Dicks (59), who probably knocked Enid Blyton off the top in 1983.

These are my reading stats for the month. 61 graphic novels, 22 audios, 20 prose, and 1 book of poetry. Fantasy and sf shared honours as top genre, 23 each. Male writers predominate, but a bit less than usual thanks to manga. 50 of the books and audiobooks were written by Americans, 54 were by writers from 13 other countries.

As usual, I'll take a month off reading now to write a novel of my own (and to finish off the next issue or three of TQF!), but I've already been thinking about how to attack my TBR list again next October. It needs to again be something that lets me switch between audio, digital, print, etc depending on where I am, what I'm doing, whether there's good lighting!

I thought about maybe reading only books with an average rating over 4 on Goodreads, so that I'd only be reading the best of the best. But filtering my Goodreads list like that produced mainly very fannish stuff, like manga and Transformers. Great works of literature are often rated lower, because of all the people obliged to read them who don't like them! For example, The Old Man and the Sea's average Goodreads rating is currently 3.8 out of 5.

A challenge of challenges could be fun, collecting together all the various reading challenges people set, like the OcTBRChallenge badges, or the Reading Glasses challenge, mush them all together, and try to complete as many as possible.

One writer friend lets a random number generator pick which books he reads, which could also be fun. I could narrow it down to only unread books up to 150pp, of which I have 1549. Maybe have a separate random generator for audiobooks. But I could easily get stuck with something short but boring.

I think my favourite idea at the moment is to start with literally my shortest book, then read a book one page longer. So say a 48pp book, then 49pp, 50pp, and see how high I can get. In parallel I could do the same with audiobooks, start with a 1hr book, then a 1hr15, etc. We'll see.

My main goal next time may seem odd, given that I've just finished 104 books and audiobooks in a month: to spend more time actually reading each day.

That's a lot of books! But it was often just a half hour for a graphic novel at lunch, an audiobook while working, a short ebook at bedtime, and so on. The only time I really got properly stuck into a book was when I was out and about, waiting for the kids at the coach station, or reading in a nearby pub while one of them was at a birthday party. I've got a lot of work on at the moment, and I do love working late after Mrs Theaker goes to bed, but I know it's not a healthy habit…

October 27, 2024

#OcTBRChallenge 2024: a third A to Z of books and audiobooks

I'm taking part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I'm trying to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I can, in A to Z order. It's been highly enjoyable. My first A to Z of the month is here, and the second is here.

I'm taking part in OcTBRChallenge again this month, and this time I'm trying to finish off as many of my short books and audiobooks as I can, in A to Z order. It's been highly enjoyable. My first A to Z of the month is here, and the second is here.This time A is for Aesthetics, a Very Short Introduction, by Bence Nanay, engagingly read by Alex Wyndham. The discussion of what it's like being on a film award jury was interesting, having just been an award juror myself. I liked the wry humour: "Being a film critic also has a pretty depressing side. You have to spend a lot of time with other film critics…" Not sure I agree with the notion that a critic isn't doing their job unless they teach you how to love a work of art. I was also interested in what the book had to say about the dangers of becoming jaded as a reviewer, if you have decided "the space of possibilities" that a film can explore before it even begins, and how it warns against making a review into nothing but a task of classification. It was interesting to learn about the "mere exposure effect", which'll make perfect sense to anyone who has gradually come to enjoy their kids' awful music, or who suddenly started to love a band they'd always hated – the Smashing Pumpkins are a good example of the latter for me.

B is for Bouncer, Vol. 5: The She-Wolfs' Prey, a violent western written by Alejandro Jodorowsky with marvellous art by François Boucq. The Bouncer helps a female hangman with a rowdy crowd but she wants to kill his dad. This left me very keen to play Red Dead Redemption 2 again!

C is for Chi's Sweet Home, Vol. 7, by Konami Kanata. She's a bit lost! I don't know how I've ended up seven volumes into a manga series about a kitten, but I guess it's a combination of (a) learning about my cat, (b) getting them all cheap, and okay (c) it being totally adorable.

D is for Dead Eyes, Vol. 1, written by Gerry Duggan. John McCrea's art is less cartoonish than usual, more dramatic, still fantastic. Dead Eyes is an infamous crook who comes out of retirement to fund his wife's healthcare. I knew within a couple of pages that I'd love this book.

E is for The End of the Fxxxing World. An American psychopath and his girlfriend go on the run after stealing his dad's car. I liked the tv show (set instead in England), but this didn't do much for me. Not much story, very few panels, lots of padding. Some decent twists, though.

F is for The Fable, Vol. 1, by Katsuhisa Minami. Things get a bit too hot for a legendary hitman and his beautiful assistant, so they are sent to live in Osaka as regular folks for a year, but violence has a way of finding them regardless. I quite enjoyed this, would read more.

G is for A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, written by Ana Lily Amirpour, with art by Michael DeWeese. Not as I assumed the inspiration for the film, but rather two issues from an unfinished adaptation of it. What there is of it is good, but an absolute cheek to sell it as a book.

H is for Honeybones, a rather brilliant novella by Georgina Bruce about the power of saying no. A teenage girl has to deal with supernatural and sexual threats, and a mum who won't talk to her any more. My first print book of the month, finished off at the Library of Birmingham.

I is for Intruders by Adrian Tomine, from the excellent Faber Stories range. It's the creepy, sad tale of a soldier between tours who accidentally acquires the keys to a house he used to rent, and starts spending the day there. Finished this outside a wedding

J is for John Carter: The End, a Dark Knight Returns for the Edgar Rice Burroughs hero of Mars, written here by Brian Wood and Alex Cox, with stylish art by Hayden Sherman. He let Dejah Thoris think their great-great-etc-grandson was dead, but the boy's grown up to be a dictator.

K is for Killing Time in America, written by Jimmy Palmiotti and Craig Weeden, with art by Justin Norman. Another unpredictable, entertaining Euro-trashy graphic novel from the Paperfilms Humble Bundle. A pseudofamily of four are sent to exact revenge upon American holidaymakers.

L is for Legend of the Scarlet Blades, Vol. 3: The Perfect Stroke, by Severio Tenuta, my first book this month by an Italian writer. In a fantastical, brutal, gorgeously-painted version of medieval Japan, a soldier visits the ruins of his home village, to recover lost memories.

M is for The Millicent Quibb School of Etiquette for Young Ladies of Mad Science, by Kate McKinnon, hilariously read by the author and her sister, Emily Lynne. As much fun as their Audible sitcom, Heads Will Roll (see our review). A Lemony Snicketish tale of a mad scientist who takes three girls under her wing. According to an SNL castmate Kate McKinnon previously wrote fantasy novels under a pseudonym, but no one knows what they were – this is her official debut. It's aimed at kids but go on, no one will judge you for listening to it.

N is for Normandy Gold, by Megan Abbott and Alison Gaylin, art by Steve Scott. The Normandy Gold of the title is a sheriff (her dad died near D-Day) who goes undercover as a high-class prostitute when her sister is killed by a john. It's grotty, exploitative and implausible, but the mystery is pretty good.

O is for Otaku Blue, Vol. 1: Tokyo Underground, written by Richard Marazon with art by Malo Kerfriden. While two unhappy cops investigate a serial killer, a post-grad student researching otaku culture makes fashion-first friends who wangle her an introduction to the ultimate legendary fanboy.

P is for The Pram by Joe Hill, a super story about a couple who move to the country after a tragedy, with horrid consequences. It's great on the stresses of having to hold it together when your partner needs you to be strong for them. And the pram is very creepy!

Q is for Quarry's Climax by Max Allan Collins, read by Stefan Rudnicki. Quarry and partner Boyd are hired to prevent the assassination of a Larry Flynt type. A later novel set back when they still worked for the Broker. Pretty good but felt quite similar to Quarry in the Middle.

R is for Requiem: Vampire Knight, Vol. 1: Resurrection by Pat Mills and Olivier Ledroit. A glitch with the Kindle version (the cover is taller than the rest of the book, so the rest of the book is unnecessarily small) doesn't spoil a crazy saga of a Nazi soldier reborn as a vampire lord in hell. Each panel could be a heavy metal album cover.

S is for Stumptown, Vol. 3: The Case of the King of Clubs, by Greg Rucka and Justin Greenwood. Portland PI Dex Parios tries to figure out why her football chum got badly beaten up after a match. Odd to read a story about football and hooliganism set in the US.

T is for The Time Invariance of Snow, by E. Lily Yu, a short, glittering ebook about the quest undertaken by G, a woman in a world where the devil's magic mirror was shattered, and the pieces fell into our eyes, distorting our perceptions of ourselves and others.

U is for Usagi Yojimbo, Vol. 34: Bunraku and Other Stories, by Stan Sakai. The ronin rabbit watches a spooky puppet show, among other short adventures. The first full volume in colour and it feels a bit odd. Is the art slightly less detailed to leave room for the colour? But the stories are as good as ever.

V is for The View from Mount Improbable by Richard Dawkins. A Penguin 70 which explains how eyes evolved, not once but many times, independently. Nice to read this after seeing him on stage in conversation this week. President of Gallifrey Lalla Ward provides the illustrations!

W is for Wunderwaffen, tome 1: Le pilote du Diable, by Richard D. Nolane and Milorad Vicanovic, set in a world where the D-Day landings failed, Hitler was badly injured by another assassination attempt, and the war went on with new armaments. Great illustrations of the planes.

X is for X, Vol. 1: Big Bad, written by Duane Swierczynski, with art by Eric Nguyen. X is Dark Horse's unpleasant, ultraviolent mix of Batman and the Punisher, and in this he kills a bunch of corrupt people as vigorously as possible. But a trap awaits and he might need a friend.

Y is for Ya Boy Kongming, Vol. 1, by Yuto Yotsuba and Ryo Ogawa. A freebie from March 2023, but if I'd realised it was about master tactician Zhuge Liang from Dynasty Warriors being reborn now and becoming the manager of a wannabe pop star I'd have read it immediately. Hilarious.

Z is for Zenith: Phase Three, by Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell. Apparently 2000 AD became a colour comic three weeks after this story ended – even without knowing that I'd wondered if it was drawn to be printed in colour, because it was so hard to follow at times. But still an epic story!

So that's my third A to Z of this year's #OcTBRChallenge complete, as well as all the challenge badges! Not sure if there's time to finish a fourth run through the alphabet before the month ends but we'll see.