Stephen Theaker's Blog, page 10

August 16, 2024

The Sky Woman by J.D. Moyer (Flame Tree Press) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in Interzone #279 (January–February 2019).

This review originally appeared in Interzone #279 (January–February 2019).Earth was abandoned long ago, as we learn from a series of interesting and all too plausible essays by Lydia Heliosmith, aged 17, for her Terrestrial Anthropology class. In 2387, the eruption of a supervolcano in the Phlegraean Fields annihilated Italy, Greece, Slovenia and Western Turkey, darkened the skies worldwide, brought the Holocene to an end, and saw the glaciers return, but the population of Earth had been in long-term decline ever since the Corporate Age. Half a million lucky people escaped to the ringstations, while the population of Earth continued to dwindle, from a peak of eleven billion down to ten thousand.

The station dwellers, genetically engineered to be geniuses in at least one field (because being a genius in two fields tended to cause mental health problems), are surprised to find people, against all the odds, still thriving down there, and begin to study them. They knew that some groups survived the initial collapse – survivalists, for example – but those had eventually succumbed to the failure of technology or the exhaustion of resources. The survivors are something different. They live in small clusters of self-sufficient communities, passing down traditional skills from one generation to the next.One such community is Happdal, to all appearances a traditional medieval village in northern Europe, but its inhabitants’ DNA reveals a diverse mixture of ethnic backgrounds – and wild strains of genetic enhancements. Village life is less idyllic than it might be. A nearby village plans a sneak attack, and about a quarter of villagers are Afflicted, falling unaccountably sick long before old age. Their lives are celebrated, and then they are burned alive on a pyre, showing their bravery by enduring the flames as long as they can without calling out for help – i.e. arrows to finish them off.

It’s now 2727. Trond, immensely strong and able to heal from injuries extremely quickly, is a blacksmith, versed in almost all the mysteries of the trade. His uncle Bjorn is Afflicted, and everyone prepares for his Burning. Trond’s mother is Elke, wife of the jarl, feared and respected by all. His younger sister Katja is fierce and a fine fighter. His brother Esper, a bowman, is brave and clever – and handsome, in the opinion of the book’s main character.

The admirable Car-En Ganzorig comes from the Stanford, a ringstation designed to hold ten to fifteen thousand people. As a particularly bright student she was given the opportunity, after eighteen months of training, to secretly study the Happdal, from a hidden camp outside their village. She wears a bioskin – a stealth suit which monitors and regulates her health, and would hide her from the locals if they weren’t so sharp – plus an m’eye, Google glasses without the social stigma.

She loves her work, but makes the mistake of trusting her advisor and mentor. Adrian Vanderplotz is happy to take the credit for her work, since watching the villagers is becoming a popular pastime on the rings, and has his own long-term agenda: he wants the first new city on the planet to bear his name. He has remote control of her biosuit and – a major source of tension in the book – its ability to dose her with drugs. His villainy is confirmed by his hatred of Tintin.

I warmed to this book slowly. The first couple of chapters didn’t astound, intrigue or promise very much, and the prose is just there to do a job, but as the novel went on it drew more arrows from its quiver. The point from which it gripped me was when Car-En sees Katja, Trond’s sister, abducted by a mysterious white-haired figure, while everyone else is distracted by the Burning of Bjorn. Car-En abandons her commitment to non-interference and uses all her skills and gadgets to pursue the kidnapper and his victim, in a thrilling sequence. If this is an ordinary man from another village, why are her drones failing?

Here the reader realises that the novel won’t just be about a clash of cultures, or a romance between two people from very different backgrounds (although it is about those things too). As the brothers and Car-En hunt Katja and her kidnapper, and as the narrative starts switching to Katja’s point of view, the book takes some unexpected turns, developing into an entertaining novel with more ideas than the first few chapters would suggest. Not every storyline is completely resolved, and sequels are presumably planned – no one from Happdal ever gets to visit the ringstations in this book, for example – but it’s a satisfying read in itself. A solid three-star book. Stephen Theaker ***

August 13, 2024

Wayward Witch by Zoraida Córdova (Sourcebooks Fire) | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

New powers and age-old struggles: young adult novel embeds real-world message in fantasy setting.

New powers and age-old struggles: young adult novel embeds real-world message in fantasy setting.In this third and final instalment in her Brooklyn Brujas series, Zoraida Córdova transposes the typical teen identity struggle onto a fantasy setting. Latina bruja (witch) Rose Mortiz is unhappy at her sixteenth birthday, which is also her Deathday, when her magical powers are bound to her. Rose is also, the author would have us know, a size 18. This detail seems random and unnecessary; rarely does it surface, and arguably, it does not shape Rose’s worldview.

Rose and her long-absent father get transported from Brooklyn to the Kingdom of Adas, on a colourful yet dangerous magical Caribbean island that tends to make people forget who they are. Will Rose remember who she is?

Rose discovers she’s one of six young Guardians with special powers. There are squabbles among them, but Rose aligns herself with a gender-fluid Guardian. Accompanied by islander siblings Iris and Arco, the Guardians go on a quest to stop a black substance called the Rot from turning rainforests into deserts. If they don’t stop this Rot, it not only destroys Adas but also impacts Rose’s world.

Though Wayward Witch exploits common themes found in young adult literature, the originality of the setting is enough to keep the reader engaged. During her journey, Rose will encounter everything from flowers that eliminate sores and walking mermaids who drink rivers to translucent frogs whose poison causes people to express their fears, but she’ll also discover something even more important: self-confidence via an understanding of her powers and their usefulness. Wayward Witch also endorses cooperation and environmental preservation – these young people want to save the fantasy world, and they eventually work toward that goal together.

Rose is known as Lady Siphon because of her special power: the ability to hack others’ powers, weaken them, and use those powers against them. Alas, she considers this a substandard power, and the nicknames – hacker, leech, devourer – don’t help. She must learn to accept and control this power, which could translate to any skill a young woman has.

Iris and Arco, whose father king supposedly seized the throne from his corrupt father, offer a diverting side story. Though Rose has a crush on the latter (an attractive horned scribe), it’s Iris, with her freckles, pink hair, pointed ears, and eyes like pink jewels, who’s the more absorbing sibling. Initially, Iris appears harsh, but Rose gradually discovers more about the warrior princess and why she seems so angry at her father and brother. Douglas J. Ogurek***

August 9, 2024

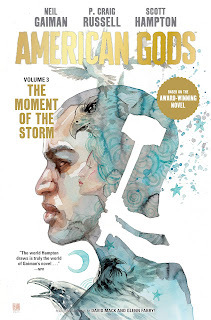

American Gods, Vol. 3: The Moment of the Storm, by Neil Gaiman, P. Craig Russell and Scott Hampton (Headline) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review was originally written in September 2020 for a previous iteration of the British Fantasy Society website, and then appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).

This review was originally written in September 2020 for a previous iteration of the British Fantasy Society website, and then appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).The third in a series of graphic novels adapting Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods. An old god has been murdered. Shadow has been invited to meet the new gods at the putative centre of the USA, to take possession of the body. Once that is done, he will serve a vigil, tied to a tree next to the body, for nine days and nine nights without water. Meanwhile, the old gods and the new are massing for battle, to fight over a country that hardly cares about any of them.

Readers who recognise P. Craig Russell’s name on the cover may be surprised by the art style within; it’s nothing at all like his elegant, stylish work on Elric or Conan. This is because, rather than being the principal artist, he provides scripts and layouts for Scott Hampton to work from. The book’s cover is by David Mack, in a different style again, while Glenn Fabry provided the spectacular covers for the original Dark Horse issues, used here as chapter title pages.It took me a little while to warm to Scott Hampton’s style. It has the slight uncanniness that can sometimes result from photo-referencing, perhaps because it’s quite unusual to see correctly-proportioned humans in comics. And some early panels are a bit plain. But as I got used to the style I grew to like it very much. Photo-referencing often seems to produce a greater variety of facial expressions, a huge benefit for a comic that is so much about character, and as the book goes on there are much more fantastical and exciting things for Hampton to illustrate. Shadow’s visionary experiences while tied to the tree are particularly well done.

The book as a whole is very good. It certainly feels like a comic in itself rather than an adaptation or an illustrated novel. There isn’t the over-abundance of captions and dialogue that can sometimes spoil such projects. It feels appropriately epic, and some sequences have the feel of true myth, if you’ll excuse the oxymoron. If this were slotted into Michael Gibson’s Gods, Men & Monsters from the Greek Myths (a childhood favourite that this frequently brought to mind), sans the modern accoutrements, no one would notice the deception. Stephen Theaker ****

August 5, 2024

Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between I: The Weird Tale – Rafe McGregor

The first of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by framing first thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post introduces the weird tale.

Wyrd, Weyrd, Weird

‘Weyrd’ came to Middle English in the fifteenth century from the OldNorse urðr via the Anglo-Saxon wurd and Old English ‘wyrd’. Itsmeaning in the ancient languages was twofold, denoting both personal destiny and thepersonification of personal destiny in the three deities that tended Yggdrasil(the Norse tree of life), who were known as the Norns. A thinly-disguisedversion of the Norns appears in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (first performedin 1606), where they are called the ‘weyrd’ or ‘weyward’ sisters, i.e. witches(like his contemporaries, Shakespeare had little interest in consistentspelling, including the writing of his own name). The Oxford EnglishDictionary identifies four distinct but related meanings of ‘weird’ inModern English:

1. Having or claiming to havethe power to control the fate or the destiny of human beings.

2. Suggestive of unearthlycharacter or strangeness that is unaccountable or uncomfortable.

3. Having a strange or unusualappearance.

4. Out of the ordinary, odd,fantastic.

We can summarise these by conceiving of ‘the weird’ as supernaturalrather than natural and uncommon rather than common, but this isn’tparticularly helpful when it comes to identifying a category or genre offiction. Almost all speculative fiction, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein;or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune series(2021, 2024), could be described as supernatural and/or uncommon.

A popular route out of this impasse is to identify the weird with theuncanny. Writing for The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman compares King, Lovecraft,and Kafka: ‘Still, when you’re in the presence of the genuine, uncanny article,you know. Stephen King is tremendously imaginative, but H.P. Lovecraft is weird;Kafka is probably the ultimate weird writer.’ The concept of the uncanny as itis commonly used today, particularly with respect to literary criticism, is atranslation of Sigmund Freud’s Das Unheimliche, which was introduced inan essay published in 1919. Directly translated, ‘unheimlich’ means ‘notfrom the home’ and some critics prefer to use the more direct ‘unhomely’. InFreud’s essay, the uncanny is the return of the repressed and he explains it bymeans of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s short story, ‘The Sandman’ (1817), and Otto Rank’s TheDouble (published in 1925, but written in 1914), a psychoanalyticexploration of the doppelgänger. The core of Freud’s conception of theunhomely is that something can be simultaneously familiar and alien. In hisauthoritative The Uncanny (2003), Nicholas Royleidentifies Martin Heidegger as providing the most intense philosophicalexploration of the concept. The very premise of Heidegger’s magnum opus, Beingand Time (1927), is that what we take to be ordinary is in factextra-ordinary and uncanny. Dasein (which can be translated as ‘being-here’or, to use less abstruse terminology, ‘agency’ or ‘selfhood’) is fundamentally‘not-at-home’ in the world and Dasein itself is thus uncanny, inconsequence of which we experience Angst (anxiety). Like China Miéville and Mark Fisher, however, I don’t thinkthat the uncanny gives us the answer to what weird fiction is.

Romanticism to Modernism

Unlike Miéville, I do think that the origins of weird fiction can befound in Gothic Romanticism. In medieval art, Gothic style was distinguishedfrom Classical style by its abandonment of restraint and subtlety, deployingcaricature and exaggeration to evoke strong emotions and created with theintention of expressing the artist’s emotion rather than representing the realityin which the artist lived. As an artistic movement, the Gothic survived thetransition from the medieval to the modern in the form of architecture,specifically the Gothic Revival or Neo-Gothic that became popular in theseventeenth century. The Gothic focus on emotion, expression, and evocation meantthat interest was revived once again with the development of Romanticism acentury later. The Romantic movement elevated the significance of emotion,expression, and individualism and prioritised the natural over the industrialand the medieval over the modern. Unsurprisingly, the Romantic movement saw thedevelopment of the English novel from an experimental to an established artform and Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) is regarded asthe first work of Gothic fiction. The genre reached its apotheosis withShelley’s Frankenstein which, in turn, influenced two distinct sets ofnineteenth century precursors to weird fiction, one on each side of theAtlantic. I should mention at this point that this series will focusexclusively on the Anglophone weird, in consequence of the combination of myown ignominious monolingualism, the consolidation of the genre in America’spulp magazines in the first half of the twentieth century, and the continueddominance of English as the preferred language of its authors. This restrictionmeans that I exclude at least one exemplary author of weird fiction, FranzKafka (1883-1924). As one of the leading lights of Modernist literature, Kafkais rarely linked to pulp, popular, or genre fiction, but I agree completelywith Rothman’s characterisation.

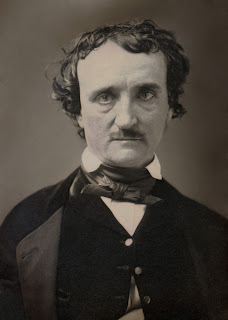

In the US, the crucial link between Gothic Romanticism and weird fictionis, of course, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849, pictured). Poe was one of the firstmasters of the short story and I regard his ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’(published in Graham’s Magazine in 1841) as the origin of both crime fictionand weird fiction. Poe was succeeded by Ambrose Bierce (1842-c.1914), MadelineYale Wynne (1847-1918), and Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933). The tradition inthe UK (actually Ireland, which was part of the UK at the time) emerged with thework of Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), who retains a reputation as one of thegreatest ghost story writers in English. Le Fanu was succeeded by Violet Paget(1854-1933, writing under the penname Vernon Lee, pictured), Conan Doyle (1859-1930),and M.R. James (1862-1936). Doyle is often underrated as a writer of horror andI have attempted to redress this imbalance in The Conan Doyle Weirdbook (2012). Ramsay Campbell claims that H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937)united and advanced the traditions in which Poe and Le Fanu were working andLovecraft acknowledged his debt to both traditions in his literary criticism.Campbell regards Lovecraft’s Mythos (which he prefers to call the Lovecraftrather than Cthulhu Mythos) as evidence of his lifelong attempt to perfect theweird tale, which involved an experimentation with prose comparable to his morelauded contemporaries in Modernist literature, such as Virginia Woolf, JamesJoyce, and Kafka. If not a part of Modernism, the weird tale is, at the veryleast, an epiphenomenon of it.

Weird Worldviews

I still haven’t answered the question of what weird fiction is or what itwas Lovecraft spent his life trying to perfect. There was little critical oracademic interest in the weird until the turn of the century and that interestis largely the result of the efforts of literary critic S.T. Joshi, who spentthe last decade of the twentieth century pioneering the field of weird fictioncriticism. In 1990, he published The Weird Tale, which was the first of hismany monographs on the genre and remains the most authoritative critical studypublished to date. Joshi identifies the weird tale as a retrospective categoryof speculative fiction that was published from 1880 to 1940 and is essentiallyrather than superficially philosophical in virtue of presenting or representinga fully-fledged and fleshed-out worldview. Although alternative definitions ofthe weird in terms of the sublime, the uncanny, and the disgusting have beenproposed, Joshi’s remains the most compelling. Lovecraft was a prolific –perhaps even compulsive – letter writer and defined his own oeuvre as cosmic horror,in which ‘common human laws and interests are emotions that have no validity orsignificance in the vast cosmos-at-large’. What distinguishes Lovecraft fromhis contemporaries, such as Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951, pictured) and Edward Plunkett (1878-1957,writing under his aristocratic title Lord Dunsany), is thus the absenceof the supernatural. Lovecraft’s monsters are not werewolves, vampires, orghosts, but aliens (although humanity is unable to distinguish the two). In hisout-of-print biography of Lovecraft, L. Spraque de Camp referred to theworldview on which Joshi places so much emphasis as ‘futilitarianism’.Lovecraft denied that he was a pessimist in another of his letters: ‘I am not a pessimist but an indifferentist – that is, I don’t makethe mistake of thinking that the resultant of the natural forces surroundingand governing organic life will have any connexion with the wishes or tastes ofany part of that organic life-process.’

With the exception of James, Joshi argues that each of the six exemplarsof the weird tale – Bierce, James, Arthur Machen (1863-1947), Blackwood, Plunkett, andLovecraft – had . I havealready suggested that Bierce and James are more accurately considered as precursorsto the weird and I think Joshi errs in omitting William Hope Hodgson(1877-1918) from his list. I came to Lovecraftmuch later than most – in my thirties – and have read his work in three cyclesin the last two decades. In the first, I was amazed, enthralled, and evenshocked by his singularity, innovativeness, and complexity. My second readingwas much more critical, identifying flaws in both his form (structure anddialogue) and content (pathological racism and casual sexism) and wondering howand why he remains so popular. More recently, I’ve come to see him as a genius for all his moral and artistic flaws, a literary equivalent of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche: two awkward, unhappy, and rather unpleasant men whose talent was unrecognised while they were alive, but whose posthumous influence is too great to calculate with any accuracy.

Recommended Reading

Edgar Allan Poe, The Murdersin the Rue Morgue, Graham’ s Magazine (1848).

Algernon Blackwood, TheWillows, The Listener and Other Stories (1907).

H.P. Lovecraft, The Call ofCthulhu, Weird Tales (1928).

Nonfiction

S.T. Joshi, The WeirdTale, Hippocampus Press (1990).

Kate Marshall, Novels byAliens: Weird Tales and the Twenty-First Century, The University of ChicagoPress (2023).

Michael Dirda, Introduction,Weird Tales, The Folio Society (2024).

August 2, 2024

Hazards of Time Travel by Joyce Carol Oates (Fourth Estate) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in Interzone #278 (November–December 2018).

This review originally appeared in Interzone #278 (November–December 2018).Found guilty on seven counts of Treason-Speech and Questioning of Authority, school valedictorian and Patriot Scholar Adriane Strohl has been sentenced to four years in Exile. She counts herself lucky. She could have been deleted, or exiled forever, or her family could have been arrested as collaborators. Instead, she has been sent to the past, to study at the University of Wisconsin. The USA of 1963, with its sexism, secondhand smoking, girdles and no internet, is almost as bad a place to be a clever woman as her twenty-first century, and by implication our present is dystopic too, in so far as it reflects them.

She comes from a future where history began on September 11, “a True Democracy [where] all individuals are equal”, so high grades are risky, especially for girls. Home Security Public Safety Oversight is one of a mulitude of repressive new organisations; experiments are no longer part of the school curriculum, just so-called facts; the politician with the most money automatically becomes the party’s nominee; and people are divided by SkinTone categories. Adriane, an ST1, has never seen an actual ST10. It all feels very heavy-handed, but maybe that’s the satire the US needs at the moment.The prose is straightforward, as if written for youngsters, but this book won’t offer teenage readers the catharsis they might expect from this genre: the plot concerns Adriane’s belief that she has identified a fellow exile, Ira Wolfman, not revolution. This isn't a novel that impresses with its sf ideas, and the characters and story could be more interesting, but overall it’s a decent read, and it does a good job of demonstrating how some things have improved since the sixties, and what the consequences could be of those gains being lost. Stephen Theaker ***

July 29, 2024

65 | review by Douglas J. Ogurek

A rudimentary plot and an overqualified protagonist. But wait… there are big guns and dinosaurs!

A rudimentary plot and an overqualified protagonist. But wait… there are big guns and dinosaurs!Keanu Reeves in Jurassic Park. Now wait a minute – that’s not Keanu Reeves, nor is it Jurassic Park. That’s Adam Driver, and he plays Mills, an earthling-like non-earthling who crash-lands on Earth when his spaceship gets hit by an asteroid 65 million years ago… when dinosaurs ruled.

When the words “Prior to the advent of humanity” appeared superimposed on a space backdrop when 65 began, I knew that the filmmakers of this man (or whatever Mills is) vs. nature story would be taking their schoolboy subject matter too seriously.

Certainly, the film has its faults, starting with a basic and cliched plot: an underdeveloped hero goes on a two-year mission to earn enough to pay for his ailing daughter’s medication. He crashes and then undertakes a journey to find a vessel that will get him home.

Then there’s this fact (in case the reader hasn’t caught on): for an individual traveling to Earth from a planet 65 million years ago, Mills acts remarkably like a modern-day American. You’d think he’d have unfamiliar emotions and ways of approaching things.

After the crash, Mills discovers one survivor among the cryogenically preserved passengers on his craft. Unfortunately, the girl Koa doesn’t speak English. He tells her that her dead parents are still alive and tricks her into attempting to climb a mountain to get to the escape craft.

The film’s greatest strength is the rapport that Mills and Koa build as they navigate the dangerous terrain. There are even moments of levity between the two. As a father, Mills knows how to build trust, and this knowledge will pay off for him more than once. Also impressive are the prehistoric threats that keep one-upping each other: just as creature A closes in, creature B storms onto the scene and attempts to tear apart Mills and/or Koa.

Near the film’s conclusion, Mills discovers a threat much more menacing than dinosaurs. I won’t give away the threat, but I will state that the threat would have caused more tension had it been more apparent to the viewer from the film’s beginning.

Although the filmmakers could have made the same film with a less talented actor than Driver, I enjoyed seeing him repeatedly sustain painful injuries only to rise and continue pursuing his objective. Douglas J. Ogurek ***

July 26, 2024

The Thief on the Winged Horse, by Kate Mascarenhas (Head of Zeus) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review previously appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).

This review previously appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).This is a charming novel set in a slightly fantastical presentish day, telling a story of sexism, betrayal, family and creative ethics. The best enchanted dolls you can buy are those of Kendricks Workshop, an Oxford family business founded in 1820 which guards its secrets so carefully that they don’t even let the female members of the family learn them all. “The women do interiors. They’ve a knack for that, because they tidy homes in real life.” Only the men may practice sorcery, imbuing their dolls with the ability to inspire specific feelings, such as Heady Optimism or Bucolic Bliss. This is a particular bother to Persephone Kendrick, stuck working in their shop and desperate to do more. Larkin is a floppy-haired young man who arrives on their eyot, a 1.6 km-long river island lying between the Thames and the Cherwell, on which a hundred families live in cottages and toil in workrooms. He claims to be descended from a long-lost branch of the family. Despite doubts as to whether this is true, the head of the family gives Larkin a job, the job Persephone always wanted, and the novel explores the consequences of this decision. I enjoyed this book very much – it reminded me of Diana Wynne Jones, albeit without the bits that make your head spin, and with a rather rude bit here and there. Persephone was an appealingly grumpy hero, and I was rooting for her throughout. I did wonder why their world was so similar to ours, with such magic in it, but perhaps the effects of the dolls were not always so strong. With luck a sequel will be forthcoming and such questions might be answered. Stephen Theaker ****

July 19, 2024

The Sea Inside Me by Sarah Dobbs (Unthank Books) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review originally appeared in Interzone #284 (November–December 2019).

This review originally appeared in Interzone #284 (November–December 2019).In a nation traumatised by a series of terrorist attacks on primary schools, people just can’t cope. So an experiment is going on in Newark-by-the-Sea. When a crime is committed, both criminal and victim have their minds wiped of the incident, the goal being to lessen the criminality of the former and the fear of the latter.

Audrey Hayes is a processing officer, assisting people as they go through the Process. At the beginning of the book she is already troubled, recognising a girl who has been made to forget a serious sexual assault, and not for the first time. Audrey has been through the process herself, as a criminal.She is now working secretly with the police to investigate sexual exploitation, but she also becomes aware of planned terrorist attacks in Newark itself. Everyone seems to know more about her than she does, and she can’t be sure if the relationships people claim to have had with her are the relationships they actually had.

The idea of wiping away memories of crime as a general rule feels so patently terrible and open to exploitation that it’s hard to imagine it actually happening. How would it address any of the issues that led to the criminality? Wouldn’t it prevent the victim taking steps to protect herself from further crime?

Science fiction writers can set up these things just for the pleasure of knocking them down. But while the hypothetical may be unlikely, that’s not always the point. How would we, being who we are, respond to it? The book’s view of how men would treat women and girls in that scenario is hard to contradict.

It’s a short book that demands the reader’s full attention – my forgetting that “the ankles” was a place name made some sentences quite confusing. The first person narrator doesn’t always make it easy, sometimes holding crucial information back from the reader for several pages.

A cover quote compares it to Philip K. Dick, and in its length, seriousness, concept and style, it does feel like a book from an earlier era. It’s all the better for it. This is a grown-up, fiercely feminist sf novel, a worthy companion to other recent works set in the UK like If Then and Zero Bomb. Stephen Theaker ****

July 16, 2024

Growing Things and Other Stories by Paul Tremblay (William Morrow) | Review by Douglas J. Ogurek

Shut up! You’re getting too philosophical and esoteric. No wait… tell me more. Experimental horror collection sprouts a spectrum of reactions.

Shut up! You’re getting too philosophical and esoteric. No wait… tell me more. Experimental horror collection sprouts a spectrum of reactions.In “It Won’t Go Away”, one of the more impressive entries in Paul Tremblay’s sometimes brilliant and sometimes baffling Growing Things and Other Stories, the protagonist discovers strange dark areas on photos of a horror writer friend who recently committed suicide. This protagonist, also a writer, begins to extract and rearrange these black spots.

Similarly, Tremblay’s inaugural short story collection gives readers odd, difficult-to-interpret dark spots. It challenges the reader to pull out excerpts, to twist them, to place them next to others. Sometimes, the beginnings of a picture emerge. Other times, the reader is left with a bunch of dark areas.

In his story notes at the back of the volume, Tremblay doesn’t offer much in terms of interpretation but rather reveals what inspired the stories. This reminds one of the irritating creative writing student who says, “It means whatever you think it means.”

These stories refuse to give clear-cut answers – the author even refers to himself as Mr Ambiguity in one story. This strategy leads to entries that vacillate from refreshing and thought-provoking to rambling and annoying. Often, Tremblay leads readers to think the story is going one way but then pulls the carpet from under them.

Without its forerunner The Cabin at the End of the World, this collection would barely make it through the front door of William Morrow. Some stories, reading like commercials for men’s cologne, leave the reader completely in the dark. Others are pontificating and cumbersome. “Notes from the Dog Walkers”, for instance, is written as a series of notes left by dog walkers at a man’s house. What starts as cute reports devolves into hulking paragraphs of self-indulgent, meandering rants that stitch together random thoughts.

The concluding story, “The Thirteenth Temple”, which resurrects sisters Merry and Marjorie from Tremblay’s innovative 2016 possession novel A Head Full of Ghosts, gets lost in a miasma of repetition and vagueness.

Despite striking out in some cases, the collection does offer some winners – several stories were so intriguing that I read them twice. One of the best entries, the Hell Boy-inspired “Her Red Right Hand,” is a beautiful exploration of the grieving process. When Gemma’s mother dies, her father turns into a sulking, drunken mess. He often retreats to his bedroom, and he says things out of anger. The girl spends time near a well, where she confronts a goblin who degrades her and, interestingly, has her father’s voice. The girl’s drawings start to create a new reality at the well. This story exemplifies the power of art in overcoming inner demons, expressed in this case as an outer goblin.

Another engrossing offering is “The Teacher,” in which a beloved high school history teacher exposes his students to “special lessons”, one of which is a paused video of a preschool boy sailing through the air toward a wall after being thrown by his teacher. As the weeks progress, the teacher slightly advances the frame, causing the suspended boy to get closer to the wall. The image captures what Tremblay is doing with most of these stories – showing people on the brink of disaster and encouraging several possible interpretations.

“The Getaway”, ostensibly about four men gradually disappearing while fleeing a crime scene, turns out to be a commentary on the repercussions of neglectful parenting.

In “Nineteen Snapshots of Dennisport”, a man reflects on photographs from a boyhood family vacation in Dennisport, Massachusetts. Most of the photos are innocuous, but the narrator gradually reveals more about his mysterious father until the story ends with a surprising revelation.

“Our Town’s Monster”, one of the entries I read twice, intrigues despite its lack of clarity. A realtor showing a home to a dull, yet attractive couple nonchalantly reveals that a monster lives in a nearby swamp. A centenarian who is supposed to be (but isn’t really) the last teacher at a one-room schoolhouse is perceived as a kind of monster. A boy attempts to frighten his ultra-philosophical younger brother at a graveyard. The brother, immersed in his extremely violent video games, isn’t having it. Tremblay seems to be commenting on the human tendency to be so wrapped up in our own issues that we don’t see the monsters right in front of us.

When I was in elementary school, I did an experiment in which I placed the same kinds of seeds in separate pots and fed each one a different liquid (e.g. water, milk, coffee, tea). While some plants rose quicker than I expected, others never even broke through the soil. In Growing Things and Other Stories, Paul Tremblay feeds each horror story with a different elixir to inspire several questions: What is a monster? When, if ever, will it surface? Or has it already surfaced? Unfortunately, all that experimentation suffers from a fair amount of muddiness.—Douglas J. Ogurek ****

July 12, 2024

Ormeshadow, by Priya Sharma (Tordotcom) | review by Stephen Theaker

This review previously appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).

This review previously appeared in TQF69 (April 2021).Bookish boy Gideon and his parents John and Clare are forced by reduced circumstances to leave Bath and return to the family sheep farm. Bath, in Gideon’s view, had been a city of graceful townhouses, where children played with hoops and oil lamps hung like magic lanterns. The children of Ormeshadow, on the other hand, stare at him in baleful silence. The village gets its name from the legend that it was built atop a dragon, but don’t read this expecting The Dragon Griaule. It’s a historical drama, tinged by the possibility of fantasy towards the end. The family farm is run by John’s resentful brother, who is far from happy that his private secretary of a brother has returned, and his children are just as aggressive: they attack Gideon the first time they are left alone with him. Tragedy will result from these wildly different families sharing a single home. I thought this was a well-written book, and the family drama rang true, though a more overtly fantastical story would have been more to my taste. I liked that the chapters had proper titles, which seems to be quite rare in fiction these days, and fellow Richard Herring fans will be interested to learn that a certain amount of stone-clearing is involved. Stephen Theaker ****