Weird Fiction Old, New, and In-Between VI: Exploring the Ecology Within – Rafe McGregor

The sixth of six blog posts exploring the literary andphilosophical significance of the weird tale, the occult detective story, and theecological weird. The series suggests that the three genres of weird fiction dramatizehumanity’s cognitive and evolutionary insignificance by first exploring thelimitations of language, then the inaccessibility of the world, and finally thealienation within ourselves. This post introduces the register of the Real.

Hearts of Darkness

Notwithstanding very fine examples by China Miéville, Caitlín R. Kiernan,and M. John Harrison, the most critically and commercially acclaimed novel inwhat is usually called the new weird and I am calling the ecological weird isalmost certainly Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014), which is the first of hisSouthern Reach Trilogy (which will be a quartet later this month) and was successfully adapted to a feature film of the same name by Alex Garland in2018 (poster pictured). I do not intend to summarise or review either Annihilationor the Trilogy here, because excellent reviews and review essays havealready been published in The New Yorker, Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, Textual Practice, and elsewhere. Instead, Iwant to sketch a literary (and cinematic) lineage for Annihilation inorder to shed light on the definition of ecological weird fiction with which Iclosed part V. The ecological weird, like occult detective fiction, shares theprimary features of weird fiction by exploring the limitations of language, theinaccessibility of the world, and the alienation within ourselves. The last ofthese is particularly important for and to the ecological weird (to the extentthat it does or does not constitute a subgenre or subcategory of the weird) andis a development of the inaccessibility of the world (which I explained interms of the world-without-us in part IV). In ecological (and other) weird fiction,we not only encounter the alien, but recognise it within ourselves and eitherresist or accept it (it is no coincidence that the third part of the SouthernReach is titled Acceptance).

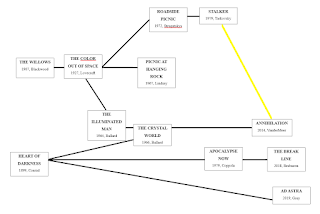

I have, in consequence, represented what I take to be the lineage fromwhich Annihilation emerged in a schematic (pictured). The link to J.G.Ballard’s The Crystal World (1966) and, by extension, to ‘TheIlluminated Man’ (published in Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1964),H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘The Color Out of Space’ (published in Weird Tales in 1927),and Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Willows’ (published in his collection, TheListener and Other Stories, in 1907) is uncontroversial. The Crystal World is a revision and expansion of ‘The Illuminated Man’ and Ballardappears to have deployed formal (and substantive) elements of Joseph Conrad’smasterpiece, Heart of Darkness (1899), in the course of adapting his ownwork. There are two points to note about this lineage. First,the inclusion of ‘The Willows’, which is – as I noted in part I – widelyacknowledged as the single best weird tale ever written, demonstrates that thethemes explored by the ecological weird are not new to the genre, merelydeveloped in a different format (typically the novel rather than the shortstory). Second, Heart of Darkness draws attention to the crux of theecological weird: it is not only about the (encounter with the) alien and (our)alienation, but self-alienation. Though criticised for its use of language and adoption of attitudes that are now, with complete justification, regarded as offensive, the novella provides a critique of colonialism so robust that it would keep plenty of social media trolls busy for a long time (assuming they had the intelligence and patience to read it). Conrad’s insightis that colonialism is not only bad for the colonised, who suffer what we wouldnow call genocide, but also for colonisers, for whom the remoteness and expansiveness of the colonies facilitates the flourishing of all that is vicious within them.Despite VanderMeer’s repeated and vehement denials that Andrei Tarkovsky’s featurefilm, Сталкер (1979, translated as Stalker),had any influence on Annihilation, I made a tenuous link in my sketch onthe basis of both narratives being concerned not only with a place that isutterly alien to humanity, but with the effects of that place on the minds ofthe people who enter it. The latter is essential to the ecological weird, the recognition of the alien within ourselves to which we respond with eitherresistance or acceptance.

The Weird Within

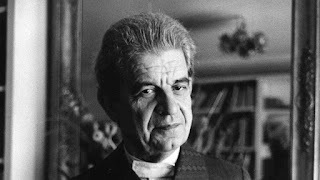

Psychoanalyst and philosopher Jacques Lacan (1901-1981, pictured) is aneven more controversial figure than Jacques Derrida (whom I discussed in partII) because he is regarded by many as a cynical (rather than sincere) charlatanand because there remains no consensus on the value of the vast body of work heproduced over a career of five decades. In contrast to Derrida (and EugeneThacker, discussed in part IV), I make no pretence to understanding Lacan’soverall project or even his individual publications and seminars, but I dothink that what is known as his register theory is useful for graspingthe self-alienation typically explored by and in ecological weird fiction. Registertheory is an account of the modes of human existence and, hence, an ontology (astudy of what exists, the way in which existing things exist, and how best toclassify and codify existing things). As an ontology, register theoryidentifies three distinct but intervolved modes of human experience or orders:reality that can be perceived, reality that is socially constructed bylanguage, and reality that remains inaccessible. The Imaginary refers tothe world that human beings understand perceptively and non-reflectively and tothe way in which human beings understand both that world and themselves asinfants, i.e. before they develop the capacity for language. The Imaginary is thereforean innocent and naïve mode of human experience in which human beings arereduced to their perceptual capacities.

The Symbolic refers to the socially constructed world,which human beings access by means of language. The rules of the Symbolic order are revealed by theinvestigation of the way in which both language and social relations functionand Lacan draws on the classic structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure, whom Iintroduced in my discussion of Derrida in part II, and Claude Lévi-Strauss, aFrench anthropologist. The Symbolic cannot be grasped in its entirety, with theresult that human beings remain unaware of structures, contexts, and exchangeswhich have a profound influence on their lives. The Real refers to theineffable world, which is detectable by human beings indirectly through theunconscious. The ineffable transcends expression and exceeds language, making it very difficult to discuss and impossible to apprehend. The Real cannonetheless be conceived as an objective reality that is inaccessible tosubjective and intersubjective perception and cognition, a kind of Kantian noumenonor thing-in-itself (see part IV). The primary means of conceiving the Real isthe unconscious, which is why register theory is a significant component inLacan’s metapsychology. What makes the threeorders or registers useful for understanding the ecological weird is that they arenot only a taxonomy of the types of thing that exist but also structure thepsyche, i.e. human subjectivity. The structure of subjectivity thus consists ofall three of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real and the Real is thealien – or weird – within, the part of ourselves that is impossible toapprehend and can only be conceived partially and indirectly.

Future Weird

Weird fiction is thriving. Perhaps not quite as much as in its heyday,almost exactly a century ago, but probably in a healthier condition given thatit is no longer tied to and dependent on a single format (the short story) orthe success of a particular outlet (Weird Tales). I want to close thisseries with a couple of observations that draw on my short-lived but veryenlightening (for me, if not my students) stint as a creative writing tutor. In part V, I discussed the importance of thedevelopment of the weird novel to the survival of the genre in the twenty-firstcentury, citing S.T. Joshi’s discussion of the trend in what he terms the modern weird tale. Joshi identifies threeways in which authors have attempted to match literary intention withcommercial demand by extending the tale to the novel:

1. Writing a fantasticnarrative that has a real-world setting.

2. Writing a mystery narrativewith supernatural element.

3. Writing a narrative that isstructured around a complex supernatural situation.

He regards the first of these as difficult, although Harrison’s TheSunken Land Begins to Rise Again (2020) shows how it can be achieved. Thesecond is cheating in Joshi’s opinion and while I might agree if thesupernatural element is superficial or gratuitous, I think the greater concernis that crime fiction itself is better suited to the novella format (asmentioned in part V). Nevertheless, Miéville and VanderMeer both show how thiscan be achieved (without cheating) with The City & the City and Finch:A Novel, both published in 2009. The third is Joshi’s recommended approachand assuming that Absolution doesn’t completely change the series’narrative trajectory, it seems precisely what VanderMeer has done in the SouthernReach.

While I was researching The Conan Doyle Weirdbook (2012), likely in 2009 or2010, I came across a short guide to writing new weird fiction and scribbledsome notes in the inside cover of one of the key texts I keep on my writingdesk. In spite of many hours – probably one or two days even – of searching,I’ve never been able to find the guide again. (I assume it was part of anintroduction to an anthology, but I really should have found it by now.) Thereare three recommendations and I think they present a nice complement to Joshi’slist, albeit one focused on reinventing rather than transforming the genre. Based on my notes in the absence of the original, the recommendations are:

1. Extrapolating the internal logicof a speculative (or other) narrative.

2. Rewriting a particularnarrative in a different genre.

3. Deconstructing a speculative(or other) narrative.

The first might be said to have been used by Kiernan in her extrapolation of her fascination with the figure of the selkie in The Drowning Girl: AMemoir (2012). I have heard Miéville’s King Rat (1998) described asa retelling of the Pied Piper of Hamelin (c.1300), which is bothaccurate and an example of the second. I have already provided an example ofthe third in part III, with Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom(2016), although I suspect this method would be difficult to sustain tonovel length. (I am also fairly sure that the guide was for writing new weirdtales not new weird novels). Whatever form the future of weird fiction takes, Ilook forward to reading and watching more of it in TQF and beyond!

Recommended Reading

Fiction

Jeff VanderMeer, Annihilation, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2014).

M. John Harrison, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, Gollancz (2020).

China Miéville, The City & the City, Macmillan (2009).

Nonfiction

Jeff VanderMeer, Caitlín R. Kiernan on WeirdFiction, WeirdFiction Review (2012).

China Miéville, M.R. James and the QuantumVampire: Weird; Hauntological: Versus and/or and and/or or? Collapse IV (2008).

Robert Weinberg, The Weird Tales Story (2nd ed.), PulpHero Press (2021).