Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 15

August 21, 2018

10 Lessons I’ve Learned While Working on my PhD

After nine weeks out of the pulpit this summer and after almost five years enrolled as a part-time PhD student, I’m a few weeks away (Lord willing) from submitting my thesis.

All the heavy lifting is done. All that’s left (I hope) is proofreading, cleaning up the bibliography, and fixing any formatting issues. Once I submit, I still need to travel to the UK to defend my thesis, so I’m not spiking the football just yet. But as I wrap up my study leave and head back to the church, I thought it would be worthwhile to reflect briefly on what I’ve learned over the past years–not what I’ve learned about John Witherspoon (I can write more about that later), but what I’ve learned about, well, learning. While gaining mastery in a subject area is important, a good doctoral program should do more than grant an academic degree, it should help you become a better thinker, a better student, and maybe even a better person.

With that in mind, here are ten lessons I’ve learned along the way.

1. Serious scholarship takes serious time. I’ve written a number of books, but there is a big difference between popular level writing and academic writing. I knew that in my head, but the last several years reinforced that conviction. A good popular level writer might be able to crank out a chapter in a day. A good scholar might spend all day tracking down a single footnote. That’s why real scholarship is all about momentum. You can’t write a dissertation or a journal article or a serious monograph by grabbing fifteen minutes here or there. Reading can be done in the cracks of life, but not the writing.

2. Don’t settle for abstractions. Early in my program I had to meet with a professor at the university to talk about my studies. It was one of those stressful meetings where you try to pretend that you know a lot about something you started reading about. The professor, whom I had never met before, sat in his dimly lit study with mounds of books and asked me in a serious British tone: “When did the Scottish Enlightenment begin?” I fumbled for an answer, saying something about the eighteenth-century and David Hume or Thomas Reid or Francis Hutcheson. He cut me off. “The Scottish Enlightenment did not exist until 1900 when the term was first used by William Robert Scott.” The point: look at history on its own terms, not first of all by the big terms we’ve assigned to it.

3. Read the original text. The same professor gave me the sage advice to always read the original texts, and try to read them first. Secondary sources are invaluable, but my professor was right: often they are harder to understand that reading what the person in question actually wrote. I found this to be true. I’d read chapters of commentary on Frances Hutcheson and still be unclear of what he thought. Once I read him for myself, the clouds started to part. Read texts. Read texts. Read texts.

4. You know less than you think you know. Academic work can certainly puff up. We’ve all seen (and hopefully don’t resemble!) haughty doctoral students, or recent graduates, who are at great pains to let everyone know all that they know. But done properly, graduate studies should make you humble. Do I know more than when I started five years ago? For sure. Am I more aware of all I don’t know? Absolutely. I could tell you things about Benedict Pictet or Lord Shaftesbury or the Enlightenment or the Presbytery of Paisley or the Cambuslang Revival or the formation of the Presbyterian Church in America or a dozen other things you don’t know much about. But it wouldn’t take long to get to the end of my expertise on these subjects. Once you see top notch scholarship, you realize you aren’t doing much of it! You do what you can in your specific (micro)field and stay humble about 10 million others things you don’t know.

5. The best scholars know more than you think they know. Scholarship is like any other area of humanity activity. There’s a bell curve. There are some bad scholars (who should quit their day jobs), a lot of hard working scholars making a contribution here or there (most dissertations are utterly forgettable), and then there are the few at the top who set the conversation and reshape their field–Richard Muller in post-Reformation theology, Mark Noll in the history of evangelicalism, Richard Sher in eighteenth century Scotland. And these are just a few names relative to my studies. It’s true: some people have already forgotten more than you’ll ever know.

6. But everyone makes mistakes, so get the facts for yourself. Having said all that, don’t assume the experts have it all right. And I don’t just mean their interpretations, which are always open to scrutiny. I’m talking about names, dates, and places. I found a number of honest mistakes from even the best scholars in my field (and I’m sure I made some too). Keep digging. Like Reagan said: trust but verify.

7. Good writers rule the world. Yes, a slight exaggeration. But only slight. Most students can’t write well, because most scholars don’t write well, because most people don’t write well, because writing is really hard. It’s one thing to read a lot and have a mastery of your material. It’s another thing to present your material in clear, accessible–let alone arresting–prose. To be sure, there is plenty of writing that gets assigned to us for one reason or another. But I can almost guarantee it: the writers that actually get read, and the writers you actually want to read, are writers that write well. Don’t settle for smart; work hard to communicate what you know in a way people can understand.

8. Perfectionism kills (and so does procrastination). Over the summer as people asked how my doctoral work was coming along, I often repeated the line someone told me early in the process–“There are two kinds of dissertations: perfect ones and finished ones.” That quip often kept me focused when I was tempted to spend half a day down an unnecessary rabbit trail. Of course, procrastination is the other problem that plagues most students, so I worked hard to fill out every form as soon as it was given to me, reply to every email as soon as I could, and to set realistic goals along the way that I wouldn’t let slide.

9. Learn to write with a word limit (and learn to teach with time constraints). Most dissertations have a fixed word/page count. This is, no doubt, to help the examiner who has no time (or interest) in reading 650 pages on the history of serif fonts in Ecuador. But the limits are also to help the student. What sounds like a blessing at the beginning of the process (“Hey, I don’t have to write more than this!”) will be your biggest struggle by the end of the process. Firm limits force you to be selective. You can’t say everything you want to say. You have to keep your argument moving. You have to digest, synthesize, and articulate your views, not simply chronicle what you are reading. Establishing boundaries for yourself (or for others) in writing and in speaking is one of the best ways to really grow as a thinker and teacher.

10. Doing history is about loving your neighbor. There are ten thousand things you can study, as a graduate student or as the proverbial lifelong learner. My doctoral work has been in history, and historians argue not just about history but about how to do history. Christian historians in particular argue about what it means to do “Christian history” or “history as a Christian.” For my part, I think my goal as a Christian historian is to love my neighbor as myself, and that includes my dead neighbors. That means I try to study others as I would want to be studied. If I were someone’s research project, I’d want that student to get to know me, to take me on my own terms before using me as an axe to grind, to talk about me in a way that made sense to me. Of course, others may be able to see things about ourselves that we miss. They may interpret things differently than we would. But still, the golden rule is a good goal. Work hard to understand your subject, just like you would want someone to work hard to understand you.

P.S. I know I haven’t said anything about choosing a program or what advice I would give people considering PhD work. I’ve gotten a lot emails over the past couple of years with questions about doctoral studies. I’ll try to write another post along these lines in the next few weeks.

June 17, 2018

Summer Plans

Today will (likely) be my last blog post for a couple months.

I will be out of the office, out of the pulpit, and off of social media (as much as possible) for most of this summer (June 18-August 19 to be precise).

What will I be doing?

I need to finish turning my Canons of Dort series into a book and get that to Crossway. I have a couple small encyclopedia articles to write. And I hope to visit both sides of my family at some point.

The main task, however, is to finish my PhD dissertation. I have roughly one and half chapters (out of six) left to write. The goal is to finish a draft of the thesis by the end of August, incorporate my supervisor’s feedback in September, and then formally submit in October. If all goes according to plan, I will travel to the UK in December or January to defend my thesis. I’ve enjoyed the doctoral program and am glad I undertook this journey. But now the end is in sight, and that’s a very good thing.

If you feel so led, pray for me and my family and my church as I take these two months “off” to complete my doctoral work. I am immensely grateful for this summer study leave and hope to get some rest, play with my kids, read some books, and manage to be wonderfully productive at the same time.

Grace and peace.

June 7, 2018

Toward a Theology of Apology

We need more work in the years ahead—exegetical, historical, and doctrinal—on our theology of apology.

For starters, the word itself is ambiguous. Apology can mean anything from “let me defend myself,” to “my bad,” to “I’m sorry you feel that way,” to “I repent in deepest contrition.” We could use more careful language to express what we mean (and don’t mean) to communicate.

Apologies are also complicated by history. What is our responsibility in the present to apologize for things that have happened in the past? Should Christians apologize for the Crusades? For the Salem Witch Trials? For slavery? Some apologies for the past are appropriate and heartfelt, while others feel less sincere and more manufactured.

And then there is the presence of social media, which gives us all the opportunity to make public apologies (or demand them of others). When are public apologies profound examples of humility and healing, and when do they cross the line into implicit rebuke and moral grandstanding? These are issues of the heart to be sure, but they are also biblical and theological issues.

Moving in the Right Direction (Maybe)

The “Toward” in the title of this post is important. It’s the academic way of saying, “I don’t have this all figured out, but maybe I have something helpful to throw into the mix, so here goes.” With my weasel word firmly in place, here are two suggestions for Christians as we formulate a theology of apology.

Suggestion #1

First, let’s utilize the category of corporate responsibility, but within limits.

The book of Acts is an illuminating case study in this respect. We see, on the one hand, that people can be held responsible for sins they may not have directly carried out. In Acts 2, Peter charges the “[m]en of Judea and all who dwell in Jerusalem” (v. 14) with crucifying Jesus (v. 23, 36). To be sure, they did this by the hands of lawless men (v. 23), but as Jews present in Jerusalem during Passion Week, they bore some responsibility for Jesus’s death. Likewise, Peter charged the men of Israel gathered at Solomon’s Portico with delivering Jesus over and denying him in the presence of Pilate (Acts 3:11-16). While we don’t know if every single person in the Acts 3 crowd had chosen Barabbas over Christ, Peter certainly felt comfortable in laying the crucifixion at their feet. Most, if not all of them, had played an active role in the events leading up to Jesus’s death. This was a sin in need of repentance (v. 19, 26). We see the same in Acts 4:10 and 5:30 where Peter and John charge the council (i.e., the Sanhedrin) with killing Jesus. In short, the Jews in Jerusalem during Jesus’s last days bore responsibility for his murder.

Once the action leaves Jerusalem, however, the charges start to sound different. In speaking to Cornelius (a Gentile), his relatives, and close friends, Peter relays that they (the Jews in Jerusalem) put Jesus to death (10:39). Even more specifically, Paul tells the crowd in Pisidian Antioch that “those who live in Jerusalem and their rulers” condemned Jesus (Acts 13:27). This speech is especially important because Paul is talking to Jews. He does not blame the Jews in Pisidian Antioch with the crimes of the Jews in Jerusalem.

This is a consistent pattern. Paul doesn’t charge the Jews in Thessalonica or Berea with killing Jesus (Acts 17), nor the Jews in Corinth (Acts 18) or in Ephesus (Acts 19). In fact, when Paul returns to Jerusalem years after the crucifixion, he does not accuse the Jews there of killing Jesus; he does not even charge the council with that crime (Acts 23). He doesn’t blame Felix (Acts 24) or Festus (Acts 25) or Agrippa (Acts 26) for Jesus’s death, even though they are all men in authority connected in some way with the governing apparatus that killed Christ. The apostles considered the Jews in Jerusalem at the time of the crucifixion uniquely responsible for Jesus’s death, but this culpability did not extend to every high-ranking official, to every Jew, or to everyone who would live in Jerusalem thereafter. The rest of the Jews and Gentiles in the book of Acts still had to repent of their wickedness, but they were not charged with killing the Messiah.

Does this mean there is never any place for corporate culpability across time and space? No. In Matthew 23:35, Jesus charges the Scribes and Pharisees with murdering Zechariah the son of Barachiah. Although there is disagreement about who this Zechariah is, most scholars agree he is a figure from the past who was not killed in their lifetimes. The fact that the Scribes and Pharisees were treating Jesus with contempt put them in the same category as their ancestors who had also treated God’s prophets with contempt (cf. Acts 7:51-53). It could rightly be said that they murdered Zechariah between the sanctuary and the altar because they shared in the same spirit of hate as the murderers in Zechariah’s day.

Similarly, we see several examples of corporate confession in the Old Testament. As God’s covenant people, the Israelites were commanded to confess their sins and turn from their wicked ways so as to come out from under the divinely sanctioned covenant curses (2 Chron. 6:12-42; 7:13-18). This is why we see the likes of Ezra (Ezra 9-10), Nehemiah (Neh. 1:4-11), and Daniel (Dan. 9:3-19) leading in corporate confession. The Jews were not lumped together because of race, ethnicity, geography, education level, or socio-economic status. The Israelites had freely entered into a covenant relationship with each other and with their God. In all three examples above, the leader entered into corporate confession because (1) he was praying for the covenant people, (2) the people were as a whole marked by unfaithfulness, and (3) the leader himself bore some responsibility for the actions of the people, either by having been blind to the sin (Ezra 9:3) or by participating directly in the sin (Neh. 9:6; Dan. 9:20).

To sum up: The Bible has a category for corporate responsibility. Culpability for sins committed can extend to a large group if virtually everyone in the group was active in the sin (it is telling, however, that the apostles don’t seem to think they killed Jesus, even though they were in Jerusalem at that time). We can also be held responsible for sins committed long ago if we bear the same spiritual resemblance to the perpetrators of the past. And yet, the category of corporate responsibility can be stretched too far. The Jews of the diaspora were not guilty of killing Jesus just because they were Jews. Neither were later Jews in Jerusalem charged with that crime just because they lived in the place where the crucifixion took place. And we must differentiate between other-designated identity blocs and freely chosen covenantal communities. Moral complicity is not strictly individualistic, but it has its limits.

Which leads to a second point.

Suggestion #2

Let’s try using more precise categories when apologizing for the past.

As I said at the beginning, our apologizing words don’t always mean the same thing. “I’m sorry” can mean “I feel bad that you are hurting” all the way to “I sinned against God and men.” Likewise, people may use “blame” to mean “I could have done more” or “I feel deep contrition for my wickedness.” We need some additional categories for expressing grief over wrongs committed.

I can think of at least four things we might mean by making an apology for something in the past.

Recognition: I acknowledge what happened, and I see the negative effects of those sins of omission or commission.

Remorse: I feel terrible for what has happened.

Renunciation: I reject what has taken place in the past and repudiate those beliefs, words, thoughts, or actions.

Repentance: I have sinned against God and will turn away from this evil and strive after greater obedience to God’s law in my life.

Each aspect of apology has its place, but all may not be present in every instance of saying, “I’m sorry.” Sometimes we get tied up in knots making public apologies of corporate sin because we are unsure how to repent of sins we didn’t commit, when a more appropriate (and equally salutary) step might be to recognize what happened and express our remorse over what transpired in the past, while utterly renouncing those attitudes and actions wherever they exist in the present.

[I suppose you could make restitution a fifth aspect of apologizing, but I would include this under repentance. When Zacchaeus declared his intentions to pay back four-times the amount he defrauded from others—in keeping with Old Testament law (Exod. 22:1)—Jesus took this as a sign of genuine faith and repentance (Luke 19:8-9). While the law at Sinai never tried to enforce a vision of cosmic justice whereby every inequality was abolished, it did command God’s people to make restitution for wrongs committed (Exod. 21:33-22:15) and to be openhanded to the needy (Exod. 22:21-27).]

Is There Room for We?

Of course, things get even trickier if we change those “I” statements to “we” statements. When am I responsible for something as a “we” that I may not be responsible for as an “I”? That depends on a lot of factors. We’ve already seen that Paul did not ask the Jews in Pisidian Antioch to repent of killing Jesus just because they were Jews. And yet, that doesn’t put an end to all corporate responsibility.

Consider two examples.

If you’ll permit a grim analogy, suppose you are the parent of a child who ends up a mass shooter. You raised your child with love and discipline. You didn’t encourage any destructive or hateful tendencies. You were a good (if still imperfect) parent, and your other children turned out fine. When the camera comes on you for a statement, you may not repent per se (since you don’t feel like you sinned in how you raised your now-25-year-old son), but you would certainly be right to recognize what has happened, express profound remorse (probably even saying “I’m sorry”), and renounce violence of this kind.

But consider a second example. Suppose you never disciplined your child for violent behavior. You saw his disturbing journals and did nothing about it. In fact, as a parent, you often told your son that people of color, or people with disabilities, or people with athletic chops, or pretty girls, or whatever, were losers and didn’t deserve to live. Now when you find out what your son has done, what do you say? Even though you didn’t commit a crime, you would be right to issue a “we” statement that includes repentance. Your actions played a direct role in the tragedy.

It’s messy, isn’t it? Someone can always say that you were a part of “a culture” that produced someone or something. But I think we need a tighter argument. The apostles didn’t argue that the culture of first-century Judaism killed Jesus; the Jews in Jerusalem, by the hands of the Romans, killed Jesus. Our corporate apologies would be helped if we looked at the differences between recognition, remorse, renunciation, and repentance.

Similarly, public apologies are more or less appropriate based on whether their cost is mainly to us or mainly to someone else. When someone steeped in Southern Presbyterianism apologizes in tears for the sins of the 19th-century Presbyterians he grew up revering, that costs something. When college kids, who have never been tempted in their lives to idolize Richard the Lionheart, set up confessional booths on campus to apologize for the Crusades, that costs next to nothing. One is a public expression of personal lament; the other is a personal expression of public accusation.

All of this means that the stronger the ties that bind, the stronger the argument for corporate identification. On the one hand, some Christians are quick to apologize for anything and everything (and quicker to demand apologies from everyone else). On the other hand, there are too many examples in the Bible of God’s covenant people confessing their sins together to immediately dismiss every attempt to address corporate sins of the past or the present. Even if we don’t issue a formal statement of repentance, there is still a place for churches, denominations, and other institutions to express the other three R’s. Our theology of apology must be sufficiently nuanced to allow that “We are sorry” can be appropriate even in situations where insisting on moral complicity may not be. If the Sanhedrin in AD 90 had come to Christ en masse, they wouldn’t have had to repent for killing Jesus, but we would certainly have taken it as a good sign if they had expressed the deepest remorse over his crucifixion and renounced the opposition to Jesus that lead to his death.

June 4, 2018

‘Acts: A Visual Guide’

I’ve never been good at drawing things. I learned how to master the 3D cube and Christmas trees, but that’s about it. As an inveterate grade-monger, I was thankful that my high-school art class gave good marks for working hard and showing improvement. I barely know how to color.

So it’s without exaggeration that I can say I’m amazed at what Chris Ranson has done in this new book we’ve worked on together, Acts: A Visual Guide.

You probably don’t know of Chris. I just met him a couple of years go. But what he does is impressive. While working as an engineer and a designer, this native of Scotland was introduced to the world of visual note taking. One Sunday, after years of regular sermon notes, Chris decided to try drawing (instead of writing) what the preacher was saying. At first, the sketches were pretty plain, but over time Chris found out he was quite good at this new form of note taking, and he made the mental switch to thinking in pictures.

At the beginning of 2016 I traveled to Scotland to preach a series of messages in Edinburgh. Unknown to me, Chris was there listening. He discovered that my sermons—I suppose, with their orderly Presbyterian structure and clear points and sub-points—worked especially well with his kind of note taking. A few weeks later, I was contacted by Christian Focus with some crazy idea about a Scottish guy who wanted to listen to two years’ worth of my sermons and draw pictures. I didn’t know what to expect, but I thought, Hey, why not?

The project has exceeded my expectations. Chris is not only a gifted artist, he’s also a student of the Bible and a careful listener of preaching. I’m eager to see what the Lord might do with this book—to inspire a fresh way of taking notes, to put sermons in front of people who might otherwise be disinterested, or simply to get people into the book of Acts.

The book is now available on Amazon.

June 1, 2018

Words, Labels, and ‘Sexual Minorities’

You may have heard about the upcoming Revoice Conference coming to Memorial Presbyterian Church (PCA) in St. Louis at the end of July. The goal of the conference is stated succinctly: “Supporting, encouraging, and empowering gay, lesbian, same-sex-attracted, and other LGBT Christians so they can experience the life-giving character of the historic Christian tradition.” The plenary speakers are well-known in the celibate gay identity movement, a movement in which many authors and writers are happy to embrace the self-description “gay Christian.”

Much has been written already about the term “gay Christian.” I agree with Rosaria Butterfield (among others) who find the term deeply problematic in that (1) it makes sexual orientation an accurate and essential category of personhood, and (2) it undermines the biblical notion that a desire for something illegitimate is in itself an illegitimate desire in need of repentance and grace.

While I have my concerns about some of the topics, speakers, and aims of the event, I want to comment briefly on one specific issue: the use of the term “sexual minority.” Sexual minority is a popular synonym (more or less) for those who identify as LGBT+. It is common in the wider culture and increasingly so within Christian circles. The Revoice website uses the term often. As Greg Johnson, pastor of Memorial Presbyterian, explains: “The conference organizers have preferred the term ‘sexual minority’ because it encompasses all those whose experience of sexuality is significantly different from the norm, and even includes eunuchs like the African man who was the first Gentile convert.” Johnson goes on to argue that homosexually-inclined believers should have freedom to “describe their struggle” and that the rest of us should not quarrel about words.

But of course, Paul’s injunction “not to quarrel about words” (2 Tim. 2:14) presumes that the quarrels in question are fruitless, nothing but irreverent babble, leading people into more ungodliness (2 Tim. 2:16). The fact that Paul goes on to rebuke Hymenaeus and Philetus for swerving from the truth and making false claims about the resurrection (2 Tim. 2:17-18), shows that the apostle did not always consider words to be a waste of his time.

With that in mind, I see several related concerns with the term “sexual minority.”

1. The term comes from somewhere. According to Wikipedia, “The term sexual minority was coined most likely in the late 1960s under the influence of Lars Ullerstam’s groundbreaking book The Erotic Minorities: A Swedish View, which came strongly in favor of tolerance and empathy to uncommon varieties of sexuality, such as paedophilia and ‘sex criminals.’ The term was used as analogous to ethnic minority.” Even if we care nothing for Ullerstam’s views (and I’m sure most of us have never heard of him), it is important to note that that term was coined in an effort to make deviant behavior more tolerable. My argument, then, is not that the term has to mean what some book from the 1960s wanted it to mean. Rather, my contention is that the term—whatever our intentions—has the effect of normalizing desires that are, at the least, not the way things are supposed to be.

2. The term is ambiguous. Some argue that the term is too politically correct and that it ought to include, if it doesn’t already, those with a proclivity to pedophilia, polygamy, polyamory, and all other expressions of sexuality that differ from heterosexual normativity between consenting adults. Is that what we mean by making the church a haven for sexual minorities?

3. The word “minority” is out of place. It’s troubling because it makes disordered sexual desires (which can be repented of and forgiven, just like any disordered desire) essential to one’s personhood. More to the point, in our culture, “minority” does not simply mean “less than the majority.” Minorities are considered an aggrieved group in our society. Because of the heroism of many in the civil-rights movement, and because most Americans recognize that non-whites have been mistreated in our nation’s past, any new identity that can achieve minority status is automatically afforded moral weight and authority. The term “sexual minority” is prescriptive, not merely descriptive. This is to say nothing of the legal burdens that will ensue when the language of sexual minority is added to federal guidelines and regulations.

4. The term does not do what it purports to accomplish. If the goal is to make the church a safe place for all image bearers seeking to follow Christ in faith and repentance, why would we isolate some inclinations as majority and others as minority? Why not focus on our common humanity, our need for grace, and our shared hope in the gospel, instead of forming a new class of people based on specific sin struggles?

5. The term undermines Johnson’s argument that we ought to “be sensitive to issues of personal freedom in how homosexually-inclined believers choose to describe their struggle.” Notice the last word: struggle. Our church has a ministry called Set Free, which provides biblical resources, counsel, and compassion for sexual strugglers and their families. I’m sure it’s not the only good phrase, but I like “sexual struggler” because it underlines that we are fighting against desires, temptations, and habits that we consider at odds with our commitment to grow in Christ. If someone says, “I wrestle with unwanted desires for persons of the same sex,” that indicates a struggle (even if the desires do not change and the struggle lasts a lifetime). It also suggests that these desires are not morally neutral. By contrast, “sexual minority” speaks of a settled identity. I’m not saying for a moment that orthodox Christians embracing the term do not struggle or are not daily dying to themselves in courageous ways. What I am saying is that the term suggest that sexual orientation is a constituent part of one’s identity, and a neutral, or even a positive part at that.

In short, words matter. It’s not alarmism to point out that indifference to words and definitions has often been one of the first steps to theological liberalism. I hope we in the PCA, and in the broader church, will pay more careful attention to the words and terms we use in these controversial matters. Once the labels stick, they become sticky indeed.

May 24, 2018

What Is My Calling? (And Is That Even a Good Question?)

Graduation season is upon us.

And that means in addition to much pomp and circumstance, many young people are thinking about what’s next. They are asking the question (and probably will for years to come): what is my calling?

As the Just Do Something guy, it will come as no surprise to hear that I think the language of “calling” is vastly overdone in Christian circles. Here’s what I find in Scripture:

We have an upward call in Christ to be with Jesus and to be like Jesus (Phil. 3:14). We have been called to freedom, not bondage (Gal. 5:13). God has saved us and called us to a holy calling (2 Tim. 1:9). He has called us to his own glory and excellence (2 Peter 1:3). Not many of us were called to noble things (in the world’s eyes), but, amazingly, we have been called to Christ (1 Cor. 1:26). And if called, then justified, and if justified, then glorified (Rom. 8:30).

In other words, I do not see in Scripture where we are told to expect or look for a specific call to a specific task in life.

And that includes pastoral ministry and missionary service.

Although I’ve told the story of my “call to ministry” hundreds of time, I do not see biblical warrant for thinking that God picks up the phone in a special way to dial up pastors and missionaries for their life’s work. Moreover, I worry that by emphasizing the need for a supernatural hear-from-the-Lord call to ministry, we end up convincing some people that ministry and missions are for them (when they aren’t), while unintentionally leading other people (who should be serving a church or overseas) to conclude that they can’t sign up without a special word from God.

Does this mean we should abandon the language of “calling”?

Not necessarily. There’s no rule that says we can’t take a word from our English Bibles and then use that word in a different way in normal conversation (e.g., it’s tilting at windmills to think we are going to outlaw “church” in reference to a building). But if we are going to use the language of calling outside of the biblical pattern, let’s be careful about how we use the word.

I love talking with seminarians about discerning a call to ministry if we mean, “How do I know this is a wise, appropriate step for me to take?” as opposed to, “How do I know that I’ve received a special word from God himself that I must be a pastor?” Most ministry books talk about three aspects of a call: an internal call (I desire this), an external call (I have recognized gifts for ministry and discernible fruit of maturity), and a formal call (I have been offered a position by a particular church or ministry). Those three elements make good sense as a prudent approach to making good decisions.

In fact, these three factors can be used to determine almost any kind of “call.” Should I be a doctor? Well, are you really interested in medicine and in helping people? Do your trusted friends and family members think this is a good fit for you? Is there an opportunity for you to enter into this profession? Of course, at times we push ahead in the face of opposition and try to pry open closed doors. But in general, in a society where we have many choices in front of us, it’s good advice to find something we like, something we are good at, and something that others are asking us to do.

In short, if this is what is meant by “calling”—know yourself, listen to others, find where you are needed—then, by all means, let’s try to discern our callings. But if “calling” involves waiting for promptings, listening for still small voices, and attaching divine authority to our vocational decisions, then we’d be better off dropping the language altogether (except as its used in the Bible) and labor less mysteriously to help each other grow in wisdom.

May 15, 2018

Glorify Thy Son in the Muslim World

With the beginning of Ramadan upon us, we have a good reminder to pray that the followers of Islam might become followers of Christ.

Samuel M. Zwemer (1867-1952), a graduate of Hope College (my alma mater), a professor at Princeton, and “The Apostle to Islam,” prayed for the Muslim world like this:

Almighty God, our Heavenly Father, who hast made of one blood all nations and hast promised that many shall come from the East and sit down with Abraham in thy kingdom: We pray for thy prodigal children in Muslim lands who are still afar off, that they may be brought nigh by the blood of Christ. Look upon them in pity, because they are ignorant of thy truth.

Take away pride of intellect and blindness of heart, and reveal to them the surpassing beauty and power of thy Son Jesus Christ. Convince them of their sin in rejecting the atonement of the only Savior. Give moral courage to those who love thee, that they may boldly confess thy name.

Hasten the day of religious freedom in Turkey, Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and North Africa. Send forth reapers where the harvest is ripe, and faithful plowmen to break furrows in lands still neglected. May the tribes of Africa and Malaysia not fall prey to Islam but be won for Christ. Bless the ministry of healing in every hospital, and the ministry of love at every church and mission. May all Muslim children in mission schools be led to Christ and accept him as their personal Savior.

Strengthen converts, restore backsliders, and give all those who labor among Muslims the tenderness of Christ, so that bruised reeds may become pillars of his church, and smoking flaxwicks burning and shining lights. Make bare thine arm, O God, and show thy power. All our expectation is from thee.

Father, the hour has come; glorify thy Son in the Muslim world, and fulfill through him the prayer of Abraham thy friend, “O, that Ishmael might live before thee.” For Jesus’ sake. Amen.

Surely this prayer from 1923 is worth praying every bit as much now as then. It’s amazing how the needs and challenges are still the same generations after Zwemer’s prayer.

The paragraphs above, as well as other writings from Zwemer, can be found in Islam and the Cross: Selections from “The Apostle to Islam,” edited by Roger Greenway.

May 11, 2018

Marcion and Getting Unhitched from the Old Testament

Most heresies from the early church find a way to live on in to other ages.

This is especially true of Marcionism, with its distaste for an angry God, its optimism about human improvement, and its eagerness to set aside the Bible Jesus read. From Red Letter Christianity to recent comments about our need to “unhitch” from the Old Testament, Marcionism is the evergreen heresy.

So who was Marcion and why does his revisionist project still resonate?

Marcion was born in Sinope in AD 85 in the northern province of Pontus (in what is now Turkey) on the coast of the Black Sea. Marcion, the son of a bishop, was an intelligent, capable, hard, unbending, vain, rich, ambitious man. He made his way to Rome sometime between AD 135 and 139 and was accepted as Christian into the church there. He even gave a large gift to the congregation—200,000 sesterces (worth more than a hundred year’s wages). His stint in the church at Rome, however, did not last long. He was formally excommunicated in AD 144 and his lavish gift promptly returned.

Marcion was one of the most successful heretics in the early church. He was opposed by everyone who was anyone. For nearly a century after his death, he was the arch-heretic, opposed by Polycarp (who called him the firstborn of Satan), Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement, Tertullian, Hippolytus, and Origen. He was one of the few heretics that the Greek and Latin Christians united in condemning.

After his excommunication, he traveled around the world as a missionary for his version of Christianity. And he won a lot of converts. According to Tertullian, he planted churches as “wasps make nests,” teaching men “to deny that God is the maker of all things in heaven and earth and the Christ predicted by the prophets is his Son.” Marcion’s church was rigorous, demanding, inspiring, well-organized, and for about a century fairly successful.

Marcion’s theological errors (and there were many) came from one main root: he refused to believe that the God of the Old Testament was the same as the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. Marcion simply could not believe in a God full of wrath and justice. So he threw away the Old Testament and took for his Bible a truncated version of Luke’s Gospel and selectively edited versions of Paul’s epistles. When all the cutting and pasting was finished, Marcion had the Christianity he wanted: a God of goodness and nothing else; a message of inspiring moral uplift; a Bible that does away with the uncomfortable bits about God’s wrath and hell. Marcionism was antinomian, idealistic about human potential, and skittish about dogma and rules.

Here’s how Angela Tilby describes Marcion in Heresies and How to Avoid Them (edited by Ben Quash and Michael Ward):

For him, there was a fundamental contradiction between law and love, righteousness and grace. Marcion thought that true Christianity was flawed by the incompatibilities at the heart of its teaching. His solution was radical. Nothing less than a restatement of faith would do, and for Marcion that restatement had to focus on what for him was the essential gospel: the love, mercy and compassion displayed in the life and teachings of Jesus. This, for him, was all that was necessary, it was the blueprint for a new and pure humanity. There was no other truly Christian foundation for belief or morality.

What Marcion couldn’t bear was the note of judgment that went along with the preaching of the Christian message, the warnings that came with the teaching of the law, the call to obedience and the threat of hell. For Marcion, the picture of God given at Mt. Sinai—a God whose presence is manifest in thunder and lightning, with people cowering in dread—was simply unbelievable. A God who makes his people tremble with fear, a God with whom they are afraid to communicate, could not be the God and Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. As he saw it, the Christianity of his day needed purging so that the pure gospel could be received in all its radical simplicity and appeal to the heart. Since the Bible didn’t have the God he wanted, Marcion decided to make a “better” Bible.

And so Marcionism lives on. The idea of recasting Christianity for a new day—in softer, gentler hues, more focused on the life of Jesus instead of the wrath-satisfying death of Jesus—is always popular. Some errors never quite die, and some new things are not that new.

May 7, 2018

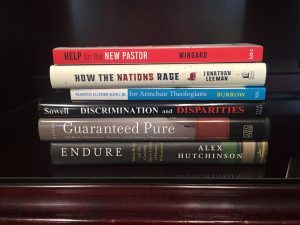

Book Briefs

As always, I have a growing stack of books I haven’t found time to read. But here are some of the ones I’ve tackled in the last month or so.

Charles Malcolm Wingard, Help for the New Pastor: Practical Advice for Your First Year of Ministry (P&R, 2018). Charlie Wingard was my pastor during my seminary years. I learned from him in the pulpit, and even more so from my time as a pastoral intern. Today Charlie teaches at RTS Jackson and pastors First Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Yazoo City, Mississippi. This book is what I would expect from Charlie: exceedingly practical and extremely wise, full of straight-shooting advice and infused with the spiritual common sense that comes from experience. Pastors will benefit from this book whether it’s their first year in ministry or not.

Jonathan Leeman, How the Nations Rage: Rethinking Faith and Politics in a Divided Age (Nelson Books, 2018). I try to read everything Jonathan writes, and I often send him my writing for his measured evaluation. Whether I agree with every jot or tittle (he is a Baptist after all!), he’s always clearheaded, tenderhearted, and thoughtful. This topic in particular—the intersection of faith and politics—is one Jonathan knows a lot about, from his years ministering in D.C. to his doctoral work on politics and ecclesiology. This would be a great book for church small groups. Jonathan helps us cut through a lot of fuzzy thinking (on both sides of the political divide) and shows us what really matters.

Rufus Burrow Jr., Martin Luther King Jr. for Armchair Theologians (Westminster John Knox Press, 2009). At T4G I asked Mike Edmondson for his recommendation on a book about King’s theology. This was his suggestion. While Burrow is a serious King scholar, this brief volume is aimed at high school seniors as well as college students wanting a basic introduction to King’s thought. Those looking for detailed theological analysis will want to go elsewhere. Still, Burrow helpfully situates King in his wider personal and intellectual context. According to Burrow, King the theologian was first and foremost a “Christian social personalist,” believing that on the cross Christ bound all people together and stamped “on all men the indelible imprint of preciousness” (59). Burrow argues that from an early age King rejected his fundamentalist upbringing, doubting the truth of the virgin birth, the inerrancy of the Bible, and the bodily resurrection of Jesus (24). Burrow positions King as a liberal theologian with a neo-orthodox corrective (i.e., more realistic about human nature), as an advocate of agape self-sacrifice and the social gospel, and as a Ghandi-inspired practitioner who embraced certain elements of Hindu thought as they related to the practice of nonviolence.

Thomas Sowell, Discrimination and Disparities (Basic Books, 2018). Those familiar with Thomas Sowell, the African American economist at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, will find the arguments in this short book to be as expected: a conservative critique against the “seemingly invincible fallacy that outcomes in human endeavors would be equal, or at least comparable or random, if there were no biased interventions, on the one hand, nor genetic deficiencies, on the other” (100). Sowell maintains that in the face of economic and other disparities among individuals, groups, institutions, and nations, most people reach one of two conclusions. Either the less fortunate are simply genetically less capable (a common belief in previous centuries), or the less fortunate are victims of those who are more fortunate (a common belief more recently). Sowell finds both explanations inadequate. He argues that disparities are owing to a variety of factors, some of which can be mitigated, but most of which are made worse by top-down solutions proposed by those with a social vision for cosmic justice.

Timothy E. W. Gloege, Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism (UNC Press, 2015). In this well-written and excellently researched book, Gloege argues that MBI rose to prominence as ground zero for fundamentalism thanks to the pioneering work of Henry Crowell, who first branded Quaker Oats as “Guaranteed Pure” and then used his business acumen to invent a fundamentalist tradition of pure Christianity for Moody. Gloege’s revisionist history is fascinating, but would have been stronger if he had allowed his subjects’ self-definition and self-assessment to trump, even from time to time, his more cynical read on their methods and motivations.

Alex Hutchinson, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance (William Morrow, 2018). With Breaking2—the 2017 Nike-led project to run a sub-two hour marathon—as his backdrop, Huthinson (a runner, columnist, researcher, and Cambridge PhD) explores the limits of athletic achievement and human endurance. This isn’t a training volume with secrets for getting a PR in your next race. Instead, it’s a journalistic examination of the different theories, studies, stories, and scholars trying to answer the simple question: what makes people keep going and what makes them stop? To that end, Hutchinson has chapters on muscles, heat, oxygen, thirst, fuel, and belief. His conclusion? We don’t finally know what makes people push through pain, but there is at least as much brain and belief involved as body and brawn.

April 30, 2018

The Preacher and Politics: Seven Thoughts

This post is addressed to preachers and is about preachers. While many of the reflections may be useful for all Christians, I’m writing specifically with my fellow pastors in mind.

We live in a day where politics is everywhere, and everything is about politics. On one level this has always been true. Jesus is Lord, not Caesar. That’s a political statement. Every sermon touches on the polis, on the city of man, on our earthly citizenship. But that’s not what I have in mind, at least not entirely. What I mean by “politics” are the elections, the elected officials, the political parties, and the endless stream of policy debates and legislative, economic, and judicial controversies that so much of our daily news and social media feed comment on constantly.

What is a pastor supposed to do with these controversies and debates? That’s my question.

When preachers are quickly criticized for saying too much (you’re not gospel-centered!) or saying too little (you’re not woke!), it behooves us to think carefully about the relationship between pastoral ministry and politics.

Here are seven thoughts.

1. Let the Bible set the agenda for your weekly pulpit ministry. I love preaching through the Bible verse by verse. I’m not smart enough to decide what the congregation really needs to hear this week. So they’re going to get John 5:1-18 this Sunday. Why? Because last week they got John 4:43-54. And in the evening they’re going to get Exodus 24, because last Sunday was Exodus 23. That means I’ve talked in the last two months about abortion, social justice, and slavery, because that’s what’s been in Exodus. I want my people to expect that as a general rule the Bible sets the agenda each week, not my interests or what I think is relevant.

2. The gospel is the main thing, but not the only thing. To be sure, we must never wander far from the cross in our preaching. But if we are to give the “whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:26-27), we must show how a thousand other theological, philosophical, and ethical issues are connected to Christ and him crucified. Thabiti is right: “A ‘gospel-centered’ evangelicalism that becomes a ‘gospel-only’ evangelicalism ceases to be properly evangelical.” The Bible is a big book. It doesn’t say everything about everything, and it doesn’t say anything about some things, but it does say a lot about more than just a few things.

3. Distinguish between the corporate church and the individual Christian. We need believers in all levels of government and in engaged in every kind of public policy debate. But there is a difference between the Bible-informed, Christian citizen and the formal declarations from church pronouncements and church pulpits. In the early part of the 20th century, most Evangelicals strongly supported the Eighteenth Amendment, the Volstead Act, and Prohibition in general. When J. Gresham Machen made the unpopular decision to vote against his church voicing support for the Amendment, he did so, in part, because such a vote would have failed to recognize “the church in its corporate capacity as distinguished from the activities of its members, on record with regard to such political questions” (Selected Shorter Writings, 394).

4. Think about the nature of your office and the ministry of your church. I studied political science in college, and I’ve read fairly widely (for a layman) in economics, sociology, and political philosophy. I have plenty of opinions and convictions. But that’s not what I want my ministry to be about. That’s not to say I don’t comment on abortion or gay marriage or racism or other issues about the which the Bible speaks clearly. And yet, I’m always mindful that I can’t separate Blogger Kevin or Twitter Kevin or Professor Kevin from Pastor Kevin. As such, my comments reflect on my church, whether I intend them to or not.

That means I keep more political convictions to myself than I otherwise would. I don’t want people concluding from my online presence that Christ Covenant is really only a church for people view economics like I do or the Supreme Court like I do or foreign affairs like I do. Does this mean I never enter the fray on hot button issues? Hardly. But it means I try not to do so unless I have explicit and direct biblical warrant for the critique I’m leveling or the position I’m advocating. It also means that I try to remember that even if I think my tweets and posts are just a small fraction of what I do or who I am, for some people they are almost everything they see and know about me. I cannot afford to have a public persona that does not reflect my private priorities.

5. Consider that the church, as the church, is neither capable nor called to address every important issue in the public square. This is not a cop-out. This is commonsense. I’ve seen denominational committees call the church to specific positions regarding the farm bill, Sudanese refugees, the Iraq War, socially screened retirement funds, immigration policy, minimum wage increases, America’s embargo of Cuba, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, global economics, green house gas emissions, social welfare, and taxation policies. While the church may rightly make broad statements about caring for the poor and the oppressed, and may even denounce specific cultural sins, the church should not be in the business of specifying which types of rifles Christians may and may not use (a real example) or which type of judicial philosophy Christians should want in a Supreme Court justice (another real example).

Again, Machen’s approach is instructive. He insisted that no one “has a greater horror of the evils of drunkenness than I” and that it was “clearly the duty of the church to combat this evil.” And yet, as to the “exact form” of legislation (if any), he allowed for difference of opinion. Some men, he maintained, believed that the Volstead Act was not a wise method of dealing with the problem of drunkenness, and that enforced Prohibition would cause more harm than good. Without stating his own opinion, Machen argued that “those who hold the view that I have just mentioned have a perfect right to their opinion, so far as the law of our church is concerned, and should not be coerced in any way by ecclesiastical authority. The church has a right to exercise discipline where authority for condemnation of an act can be found in Scripture, but it has no such right in other cases” (394-95).

6. Consider if you have been consistent. Obviously, there is a lot of talk at present about social justice and a host of issues often associated with the left. This makes people on the right a bit nervous, and understandably so. The gospel mission of the church has been buried before in an avalanche of humanitarian causes and social movements. At the same time, the concerns of the right ring a little hollow when pastors pass out partisan voter guides, tweet about the Second Amendment, sing the Star Spangled Banner in church, and then when anything about race or justice comes up, start harrumphing about politics in the church. I’m sure the same thing happens in both directions: we are fine being political until someone on the other side gets political too.

7. Be prepared to fire when necessary, but keep your powder dry. There are times when the national crisis is so all-consuming or the political issue so obviously wicked (or righteous) that the minister will feel compelled to say something. Think 9/11. Or riots in your city. Or the declaration of war. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule. Our news media, not to mention social media, make us feel like every day is a global meltdown and every hour is a moment of existential crisis. Don’t believe the hype. There is no exact formula for when you interrupt your sermon series, when you drop a blogging bomb, or when you add current events into your pastoral prayer. These things call for wisdom, not one-size-fits-all solutions. But let me suggest that when it comes to politics and public policy, parenting is a good analogy: yelling works only when it is done sparingly.