Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 16

April 23, 2018

A Needed Reminder on Monday Morning

Monday mornings can be hard on pastors.

Do you know the feeling? Like Sunday was a waste, like nothing was as good as we wanted it to be, like our efforts are doing little and accomplishing less. Most pastors can relate to the potent mix of discouragement, exhaustion, and low-level disillusionment that sets in on Monday morning (often beginning Sunday evening).

Part of the problem is we don’t know how to assess ourselves or our ministries.

Although they never set out to do it, most pastors will evaluate their ministries based on the three B’s: budget, building, and bodies. How big is your church? How big are your facilities? How big is your budget?

These aren’t bad things. Budgets, buildings, and bodies matter. It’s hard to do ministry without them. The problem is not in thinking they matter, but in thinking they are the measure.

It’s understandable how this mindset takes root, and it’s not always from rank sinfulness. It happened to me quickly in ministry as I was looking for some objective criteria to tell me that I was doing a good job. As perennial students, most pastors enter the ministry with a lifetime of letters and numbers telling them how they’re doing, where they rank, and how they measure up. We may be at the top of the class or near the bottom, but at least we get rewarded for all our hard work with some outside measurement. But after the first year of ministry, no one will tell us “You have a 3.87 GPA as a pastor” (and who would really want that feedback anyway!). Pastors are left to search for other metrics—and the three B’s fit the bill.

Almost every pastor will feel the pressure to be successful and significant. This is true no matter the size of your church, no matter your giftedness, and no matter the feedback you receive. Sometimes pastors create unhealthy expectations for themselves, and sometimes the unhealthy thinking creeps in from friends and mentors. In their book Liberating Ministry from the Success Syndrome, Kent and Barbara Hughes talk about the well-meaning advice people gave them early in ministry—advice that added up to a crushing sense of failure.

Without realizing it, the Hughes started believing certain lies about the secret to success in pastoral ministry.

Marketing: If we are visible and accessible, we will grow.

Sociology: If we contextualize and bless the community, we will grow.

Stewardship: If our people give, we will grow.

Godliness: If we are spiritual, we will grow.

Preaching: If I preach good, expositional sermons, we will grow.

Almost every pastor I know (including the one typing these words) can easily operate with assumptions like these. Hughes summed it up well: “[T]he messages kept coming to me, ‘If you will do this one thing well, your church will grow.’”

We know that’s not true, but after preaching our guts out on Sunday, we tend to forget. With apologies to Jimmy Buffet, come Monday it is usually not all right.

We need to be reminded that we can plant and water, but it’s God who gives the growth (1 Cor. 3:6).

We need to hear that final commendation again: not “Well done, good and famous servant,” but “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:21, 23).

And we need to recall that fruitfulness and effectiveness in ministry is defined as growing in godliness (2 Pet. 1:5-8).

So keep at it, pastors. Prepare one more week. Pray one more time. Preach one more sermon. And pursue God again and again. There’s no guarantee that we’ll see earthly success. But there is a promise from heaven that God will never leave you nor forsake you (Heb. 13:5).

April 16, 2018

Racial Reconciliation: What We (Mostly, Almost) All Agree On, and What We (Likely) Still Don’t Agree On

There may not be any subject more difficult to talk about publicly in this country than racial reconciliation. And in writing that first sentence, I realize some people don’t even like the term racial reconciliation! So feel free to substitute “race,” “racism,” “ethnicity,” or another term that says we’re “talking about Black-White tensions in this country.”

Of course, those aren’t the only racial tensions worth exploring, but Black-White is the racial relationship most fraught with pain and difficulty in American history. While many things in this post are relevant to a variety of majority-minority relationships, what I have chiefly in view is the relationship between African Americans and white descendants of Western European nations (i.e., people like me).

One more definition before getting to the point. The “we” in my title refers to Bible-believing, Jesus-loving, gospel-celebrating, sanctification-seeking, church-going Christians. “Evangelical” is what I have in mind by “we,” but I understand that this term is problematic for many. Nevertheless, I want to make clear that I’m not writing about Americans in general. I’m writing about Christians. And not just any Christians, but serious and sincere Christians—the sort of people, I’d like to think, who read blogs like this one. I have in mind honest, humble Bible men and women who are willing to thoughtfully listen and candidly engage in this difficult conversation, without trying to score cheap points or demonize those who disagree.

With all that by way of preface, let me be so bold (or foolish) as to attempt a list of things we (mostly) agree on and things we (probably) still don’t agree on. I don’t offer this as a comprehensive summary of recent conversations, nor do I list these things because they are the only things that matter (let alone, to suggest that the disagreements don’t really matter). What’s more, I don’t presume that the disagreements necessarily break down along racial lines. We mustn’t think that any racial or ethnic group is monolithic. These are disagreements I see among American Christians (of all kinds) about racial reconciliation, not necessarily divisions between Blacks and Whites (though they often are that too). I admit that my criteria for determining “agree” and “disagree” is subjective (e.g., blogs I’ve read, tweets I’ve seen, messages I’ve heard, conversations I’ve had), but perhaps working through an imperfect list like this can help us see how much we do agree on already and help us clarify what our continuing arguments are really about.

1. Racism

We agree that all people are made in the image of God and deserving of honor, respect, and protection. Every notion of racial superiority is a blasphemous denial of the imago dei (Gen. 1:27). There is no place for racial prejudice and ethnic favoritism in the church (Gal. 3:28; James 2:1). Where bigotry based on skin color exists, it should be denounced and repented of (Eph. 2:14; 1 John 3:15).

We do not agree on what else counts as racism or the degree to which our cultural, civic, and ecclesiastical institutions are basically race-blind, racialized, or outright racist.

2. Racial Disparities

We agree that there are deep and disturbing differences between Blacks and Whites when it comes to a variety of statistical measurements, including: education, employment, income, incarceration, home ownership, standardized test scores, single-parent households, and participation at the highest levels of leadership in business, academics, athletics, and politics.

We do not all agree on the reasons for these disparities, whether they are owing to personal choices, cultural values, families of origin, educational opportunities, structural racism, a legacy of oppression, or a combination of these and other factors. Likewise, we do not agree on the best approach to closing these gaps. Some favor political measures, others focus on educational reform, others emphasize church planting and discipleship, while others work for cultural renewal and community development. Many Christians see the need for all of the above, but even here there is disagreement about what the church’s focus should be.

3. Martin Luther King Jr.

We agree that MLK was a courageous civil-rights activist worth remembering and celebrating. MLK was used by God to help expose racial bigotry and overturn a corrupt system of Jim Crow segregation. King’s clearsighted moral convictions about racism, his brilliant rhetoric, and his example of non-violence in the face of intense hatred make him a heroic figure in American history.

We do not agree on how gospel Christians should celebrate this legacy. While most people acknowledge that King held unorthodox theological positions and was guilty of marital infidelity, we are not of one mind on how these matters should be discussed or how they relate to his overall contribution to American and ecclesiastical life. In a similar vein, we do not agree on how to evaluate the legacy of clay-footed theologians like Jonathan Edwards or Robert Lewis Dabney.

4. American History

We agree that our history has much to celebrate: far-sighted leaders, Judeo-Christian ideals, commendable heroes, technological innovation, and military sacrifices. There are many reasons we can be proud to be Americans.

We do not agree on whether our history should be remembered chiefly as one of liberty and virtue, (spotted with tragic failures and blind spots), or whether our national story (despite many noble exceptions) is more fundamentally one of hypocrisy, prejudice, and oppression.

5. Current State of Affairs

We agree that race relations have come a long way in the past 50 years. Things are better than they used to be. We also agree that racism still exists and that even if we play by the rules and pursue the American Dream with the same effort, we do not all begin at the same starting line or experience the same success.

We do not agree on whether our cultural, political, and academic institutions are basically fair (with exceptions) or basically rigged and in need of structural change (with repentance for the majority’s part in perpetuating systemic bias). For example, in just the last year I read a thoughtful book by a white man arguing that the deck is stacked (by Whites), and has always been stacked (by Whites), against African Americans. I also read a thoughtful book by a black man arguing that racism is largely a thing of the past and that focusing on Black victimhood is self-defeating. (I realize, of course, that neither book is representative of the way most Whites and Blacks think, respectively, of the issue.)

6. Corporate Responsibility

We agree that it is appropriate, in some situations, for Christians, for Christian institutions, and for churches to be rebuked for corporate sins and to repent of corporate failures. The Old Testament prophets often denounced the nation of Israel, even though individuals within the nation were certainly living lives of holiness and integrity. Likewise, we see that Daniel offered a prayer of confession for his people, even though he likely was not personally guilty of all the sins he confessed (Dan. 9:1-19). In the New Testament, we see that the Jews were held responsible for Christ’s death, even though there were some Jews who followed Jesus and lamented his death.

We do not agree when and how—and in many situations whether—this corporate accountability and repentance should take place. We do not agree on how (or if) the passage of time, racial identity, and ecclesiastical affiliation should shape these matters. Similarly, we do not agree what should be done, if anything, beyond repenting for corporate sin.

7. Politics and the Church

We agree that the church of Jesus Christ must not be beholden to any political party. We agree that the church is neither competent nor called to offer opinion on the specifics of every political debate or policy discussion. Preachers should, as a general rule, preach verse by verse through the Bible, letting God’s word set the agenda, rather than riding hobby horses or trying to respond to the latest controversy. At the same time, we agree that Christians, churches, and pastors should not be silent on matters of justice about which the Bible clearly speaks.

We do not agree on how the “spirituality of the church” applies in every situation (or if it is a biblical idea in the first place). At its best, the “spirituality of the church” roots us in the explicit teaching of Scripture and helps us keep the main thing the main thing. At its worst, the “spirituality of the church” has been used to ignore evil in our midst and sidestep issues of biblical obedience. While we recognize that the gospel is of first importance and that the gospel has public ramifications, we do not always agree on how these two convictions play out side-by-side in real time. There is little agreement on which issues are “moral” and “biblical” and which are merely “political.”

8. Systemic Injustice

We agree that sin is not just a matter of individual responsibility. It is possible for systems and structures to be unjust even when the people inhabiting those systems and structures may not have personal animus in their hearts.

We do not agree on whether disparities themselves indicate systemic and structural injustice (see above). Likewise, we do not agree on the best remedies for institutional racism where it exists.

9. Police and Judicial System

We agree that our country imprisons far more of its citizens than any other nation does. We also recognize that minorities are imprisoned at rates disproportionate to their population as whole. The presence of mass incarceration has a deleterious effect on many minority communities and families, as well as in the lives of those who are imprisoned.

We do not agree on the reasons for mass incarceration or whether the disproportionate imprisonment of minorities is a sign of entrenched bias. We do not agree on the nature of policing nor on the state of our judicial system, whether both are (largely) fair and colorblind or whether both are prejudiced (intentionally or unintentionally) against persons of color. By the same token, we often respond very differently to stories involving the police and African Americans, either siding instinctively with law enforcement officers or assuming that each questionable encounter is another example of pervasive police brutality.

10. Sunday Morning

We agree that the biblical vision of heaven is a glorious picture of a multi-ethnic throng gathered in worship of our Triune God. We would rejoice to see our churches reflect this biblical vision more and more. To that end, we lament the cultural blind spots we have (and don’t know we have!) which make it more difficult for people unlike us to feel at home and be in positions of leadership and influence in our churches.

We do not agree to what degree this “segregation” on Sunday morning is the result of present sin, historical sin, personal preference, unfortunate cultural ignorance, or understandable and acceptable differences in worship and tradition. We do not agree on whether all churches must be multi-ethnic, should at least strive to be multi-ethnic (as their location allows), or whether there are ever justifiable reasons (and if so, what those reasons are) for a church to be entirely (or nearly) mono-cultural. And if the pursuit of racial diversity is desirable, we do not agree on whether this multi-ethnic vision is just for predominately White congregations, conferences, and communities or if it also applies to historically Black churches, conferences, and communities.

11. The Church and the World

We agree that the Bible calls the church to be honest about its own sins (1 Peter 4:17) and to keep itself unstained from the world (James 1:27). As salt and light, we should be distinct from the world, while at the same time having a salutary effect on the world.

We do not agree on which is the more urgent need of the hour, to repent of our sin and renew our witness in the world, or to spotlight sin in the world and keep ourselves free from its corrupting influence. We know both are necessary, but our personal and corporate inclinations often lean in one direction more than the other. Likewise, we often disagree on what urgency looks like in racial reconciliation and whether this conversation should or shouldn’t take precedence over other moral issues like protecting the unborn and defending biblical marriage and sexuality.

Why This Matters

I’m sure I missed some important categories, and some of my own leanings probably show through in the way I’ve framed the issues. But as much as possible, I tried to state the agreements and disagreements fairly and matter-of-factly.

“To what end?!” You may ask. Toward several ends.

First, in laying out a list like this, perhaps we’ll be able to better isolate what it is we are arguing about at any given moment. With racial matters, we are often guilty of making every conversation about everything else. So even though the disagreement started off by talking about colonial American history, we ended up arguing about Donald Trump, mass incarceration, and corporate repentance. To be sure, sometimes everything is connected to everything, but I still maintain that our conversations will produce more light than heat if we can focus in on one argument at a time.

Second, my hope is that if we can focus on specific disagreements, rather than meta-complaints, we’ll have a better chance of putting forward constructive criticisms and thoughtful rejoinders. I don’t deny that “racism” is a thing, just like “cultural Marxism” is a thing, but let’s be careful not to smother our opponents in labels when we should be respectfully piling up facts and arguments instead. Being “slow to speak” doesn’t mean we can never say anything. It means we try to understand, try to sympathize, and try to explain instead of dismissing our (good faith) interlocuters out of hand or stigmatizing them with unwanted names and isms.

And finally, maybe a list like this can help us put our arguments in the appropriate categories. Let me be clear: all of the disagreements above are important, and Christians should be engaged in all of these debates. By laying out these disagreements, I’m not suggesting we now ignore them or act as if no answer is better than another. And yet, we ought to recognize that some of these disagreements are biblical and theological (e.g., the nature of corporate repentance, the entailments of the gospel, the dignity of all image bearers), while others are matters of history or policy, while still others require a good deal of expertise on sociology, law, economics, and criminology. By more carefully isolating our real disagreements we will be better equipped to talk responsibly, listen respectfully, find common ground, and move in the direction of possible solutions.

April 9, 2018

Four Suggestions for T4G

This week is always one of my craziest, busiest, most wonderful, most hectic, most edifying weeks of every even year. Like many of you (and probably others that you know) I will be in Louisville this week for the Together For the Gospel conference. It’s always a tremendous time to sing, to learn, to listen, to laugh, to see old friends, to make new friends, to be amazed again by the gospel (and try as hard as I can to squeeze in a run in the midst of so much sitting).

Big conferences will never be one iota as important as the local church. Full stop. And yet, they can play a role in strengthening and supporting local churches and local church pastors. That’s always been the heartbeat of T4G.

So how might you benefit from a conference like T4G, and how might the benefits you receive be a blessing to your local church?

Here are four suggestions.

1. Be thankful. Thank God for the singing, for the resources, for the teaching, for the people serving you at the hotel and in the restaurants, for the people (you may never know or meet) who have worked and will be working tirelessly behind the scenes to make a massive event like this possible. Thank God for the freedom to gather in large numbers to learn and worship. Thank God for his work in recent years to stir up a passion for his glory, a hunger for good preaching, and a love for the particularities of the gospel. And when you return home, thank God for your local church and for your pastor.

2. Pray. I know the schedule is nuts, but it would be a shame to go prayerless for three days at a gospel conference. Pray for the speakers and the organizers. Pray for your fellow pastors and pastors’ wives. Pray for the churches represented. Pray for safety. Pray for conviction of sin and the comfort of the gospel. Pray for the result of our gathering to be greater humility before God, greater fidelity to the Scriptures, greater integrity in our ministry, and greater harmony in our families. Pray for people to get saved. Pray for preachers to be renewed. Pray for churches to be revived, encouraged, and strengthened.

3. Stand against the devil. Resist the many temptations that can fly into our hearts in a week like this: temptations to jealousy and envy, temptations to bitterness and despair, temptations to compare and criticize, temptations to be haughty and proud, temptations to impress instead of to serve. Be mindful of the accusations and deceptions of the Evil One. Our battle is not against flesh and blood.

4. Take something home. No doubt, you’ll be stuffed full of teaching, conversation, and free books by the end of the week. No one should go away empty. But it’s wise to be strategic with all you’ll receive. You may want to think in terms of the one thing(s) you will take home: one new song to share, one practical suggestion to implement, one new idea to ponder, one new friendship to cultivate, one new book you will definitely read, one sermon to revisit, one doctrine to study, one habit to create (or give up), one Louisville Slugger for each of your non-violent children. Most of what you hear and see will fade from memory. That’s life. But that doesn’t mean you can’t take something that will stick with you and your people for a long time.

April 2, 2018

In My Place Condemned He Stood

Late last week, just in time for Good Friday, Christianity Today published an article entitled “Is the Wrath of God Really Satisfying?” It was written by Thomas McCall (professor of biblical and systematic theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School), presumably as a distillation of the arguments he makes in Forsaken: The Trinity and the Cross, and Why it Matters (IVP, 2012). As a Christian (and pastor and professor) who believes in penal substitutionary atonement—that Christ died in our place to assuage the wrath of God—I found McCall’s article helpful in places, but also confusing and misleading. After reading it several times, I’m still not sure if McCall is trying to undermine penal substitution, rescue it from abuse, or avoid it altogether.

At the very least, given the timing and the title, the article felt like a poke in the eye to the millions of Christians who believe that Good Friday is good precisely because Christ was stricken, smitten, and afflicted by God for our sake.

Ruptured Trinity

The main burden of McCall’s piece is to show that some popular preaching on the cross is at odds with orthodox Trinitarian theology. According to McCall, “God against God” theories of the atonement imply (or explicitly teach) that God’s Trinitarian life was ruptured on Good Friday. And yet, McCall argues, God could not turn his face away from the Son, because the Father is one with the Son. “To say that the Trinity is broken—even ‘temporarily’—is to imply that God does not exist.”

While I’m not convinced that Christ bearing the wrath of God implies a Trinitarian fissure, McCall is right to warn against misreading the cry of dereliction in literalistic fashion, as if the first person of the Trinity was coming to blows with the second person of the Trinity. Whatever else it might mean, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” does not mean that the eternal union of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit was interrupted. We should be careful not to speak of the Son suffering in complete absence from the Father, or speak as if the Father was disgusted with his Son on the cross.

As usual, Turretin explains the matter—in this case the “punishment of desertion” (Matt. 27:46)—with careful precision. The desertion on the cross was not “absolute, total, and eternal (such as is felt only by demons and the reprobate), but temporal and relative.” Likewise, the desertion Christ experienced was not with respect to “the union of nature,” nor “the union of grace and holiness.” Neither was Christ deprived of the Father’s “communion and protection.” Instead, God suspended “for a little while the favorable presence of grace and the influx of consolation and happiness.” In other words, the Son’s “sense of the divine love” was “intercepted by the sense of divine wrath and vengeance resting upon him” (Elenctic Theology 13.14.5). Whether McCall would approve of that last line or not, clearly Turretin meant to affirm Christ’s forsakenness in a way that avoids any notion of Trinitarian rupture.

Incidentally, although McCall dings R. C. Sproul for his explanation of Christ’s accursedness, it seems to me Sproul was trying to make the same point as Turretin: “On the cross, Jesus entered into the experience of forsakenness on our behalf. God turned his back on Jesus and cut him off from all blessing, from all keeping, from all grace, and from all peace.” This sounds more like withholding “the favorable presence of grace” than a Trinity-busting Father-Son brouhaha.

Scream of the Damned

McCall is also concerned that some popular notions of the cross turn Christ into the damned of God. To be sure, we must be careful with our language. The Son of God experienced the horrors of damnation, but he was not himself damned. It would be better to say that Christ’s sufferings were hellish or that he bore the weight of eternal punishment than to say that Christ entered the place of the damned.

Again, Turretin is helpful:

As he is properly said to be damned who in hell endures the punishment due to his own sins, this term cannot be applied to Christ, who never suffered for his own but for our sins; nor did he suffer in hell, but on earth. Still there is no objection to saying that the Son of God was condemned for us by God, just as elsewhere he is said to have been made a curse and malediction for us. (Elenctic Theology, 13.16.10)

Does this mean Sproul was wrong to speak of “the scream of the damned”? Granted, the phrase is provocative and easily misunderstood. It’s not a phrase I would use, but we should remember—and here I’m using McCall’s own quotation—that Sproul said it was “as if a voice from heaven said, ‘Damn you, Jesus’” (emphasis mine). Sproul’s use of the phrase was homiletical/metaphorical more than technical/analytical, although I see McCall’s point (and Turretin’s).

How Does This Work?

The CT article makes clear what McCall does not believe about the cross:

There is no biblical evidence that the Father-Son communion was somehow ruptured on that day. Nowhere is it written that the Father was angry with the Son. Nowhere can we read that God “curses him to the pit of hell.” Nowhere it is written that Jesus absorbs the wrath of God by taking the exact punishment that we deserve. In no passage is there any indication that God’s wrath is “infinitely intense” as it is poured out on Jesus.

If this is what did not happen on the cross, then what did take place? McCall believes in sin and guilt. He also affirms the wrath of God, but how he thinks this wrath is turned away was unclear to me. He says, “the Son enters our brokenness and takes upon himself the ‘curse’ caused by humanity’s sin.” McCall acknowledges that the Old Testament bears witness to “both the wrath of God and the sacrifices offered for sin” and that the New Testament “draws these connections” and presents Jesus as our sacrifice and substitute. Elsewhere he says, “Christ came to get us out of hell” and that “Christ’s sacrificial work saves us from the wrath of God.”

If on the cross as Jesus died, the wrath of God was not satisfied, how was it then appeased?

So how does this happen if Jesus did not absorb the wrath of God? It’s good to point out the New Testament “connections” between wrath and sacrifice, but what specifically is the connection? How does Christ’s sacrificial work actually save us from the wrath of God? Most evangelical Christians would affirm that “Christ sustained in body and soul the anger of God” (Heidelberg Catechism, Q/A 37). As the curse for us (Gal. 3:13), Christ reconciled us to God, making a way for a just God to justify ungodly sinners (Rom. 3:21-26). Just like the bloody atonement of old, Christ’s death was a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God to atone for our sins (Lev. 1:9, 13, 17; Eph. 5:2). In fact, the very notion of propitiation implies that God’s righteous anger had to be assuaged (Rom. 3:25; Heb. 2:17; 1 John 2:2; 4:10). Christ did not feel forsaken by God for no reason. To be sure, the Trinity was not broken on Good Friday, but it was still “the will of the Lord to crush” the suffering servant (Isa. 53:10). If on the cross as Jesus died, the wrath of God was not satisfied, how was it then appeased?

Better Way

In support of his overall argument, McCall enlists two Reformed heavyweights. He quotes John Calvin to the effect that the Father could not be angry with his beloved Son, and then quotes Charles Hodge denying that Christ’s death was a quid pro quo arrangement where the Son suffered exactly what sinners deserved. Both quotations are accurate and important, but given their original context I wonder if they help McCall’s case or point us in a different direction.

Calvin’s statement is part of a larger discussion about the cry of dereliction in Matthew 27:46. Calvin rejects the ideas that Jesus was merely expressing the opinion of others or using Psalm 22 to give voice to Israel’s lament. No, “his words were drawn forth from anguish deep within his heart.” Christ felt himself forsaken and estranged from God.

And then comes the line McCall quotes: “Yet we do not suggest that God was ever inimical or angry toward him. How could he be angry toward his beloved Son, ‘in whom his heart reposed.’”

But notice Calvin’s next sentence: “How could Christ by his intercession appease the Father toward others, if he were himself hateful to God?” Clearly, Calvin does not see the idea of wrath-satisfaction as being at odds with unbroken Father-Son communion. “This is what we are saying,” Calvin continues, “he bore the weight of divine severity, since he was ‘stricken and afflicted’ by God’s hand, and experienced all the signs of a wrathful and avenging God” (Inst. 2.16.11).

We should never say that on the cross, the Father hated the Son. And yet, we can say—and must say if we are to make sense of the cry of dereliction in Matthew 27 and the curse language of Galatians 3—that Christ, bearing the imputed sin and guilt of his people, bore the wrath of God in our place. As Calvin says later, “If the effect of his shedding blood is that our sins are not imputed to us, it follows that God’s judgment was satisfied by that price” (Inst. 2.17.4).

We see something similar when we examine Hodge’s larger argument. In discussing the atonement, Hodge highlights two kinds of satisfaction. The one is “pecuniary or commercial,” as when a debtor pays the demands of his creditor in full. This is the quid pro quo (this for that) arrangement Hodge rejects. Christ does not satisfy our debt in a commercial sense, because in a commercial transaction all that matters is that the debt is paid. It doesn’t matter who pays it or how it gets paid, so long as the debt is covered. The claim of the creditor is upon the debt, not upon the person.

It’s hard to understand why Christ would ask for the cup to be taken from him unless he believed it to be the cup of God’s wrath that he would drink to the bitter dregs for sinners like us.

The other kind of satisfaction, and the kind Hodge approves, is “penal or forensic,” wherein Christ makes satisfaction not for a generic debt but for the sinner himself. Christ’s “death satisfied divine justice” because it “was a real adequate compensation for the penalty remitted and the benefits conferred.” True, as McCall points out, Hodge maintains that Christ “did not suffer either in kind or degree what sinners would have suffered.” But this should not be construed as an argument against penal substitution. For in the next sentence Hodge affirms, “In value, his sufferings infinitely transcended theirs. . . . So the humiliation, sufferings, and death of the eternal Son of God immeasurably transcended in worth and power the penalty which a world of sinners would have endured” (Systematic Theology, 2:470-71).

Hodge would agree with McCall’s point that Christ did not suffer exactly what sinners deserve, but would McCall agree with Hodge that Christ suffered the weight of what sinners deserved? More to the point, would he agree with Hodge’s understanding of forensic satisfaction? “The essence of the penalty of the divine law,” Hodge writes, “is the manifestation of God’s displeasure, the withdrawal of the divine favor. This Christ suffered in our stead. He bore the wrath of God.” For sinners this would lead to “hopeless perdition,” but for Christ it meant “a transient hiding of the Father’s face” (473). And lest this be confused with a breach of Trinitarian relations, Hodges makes clear that the “satisfaction of Christ” was a “matter of covenant between the Father and the Son” (472).

Granted, McCall is from the Wesleyan-Arminian tradition, so he may deny all that Calvin and Hodge affirm. But at the very least, they show us a way to deny what McCall wants to deny—a crass Father versus Son Trinitarian breach—while still affirming a wrath-satisfying, God-appeasing, Father-turns-his-face-away penal substitutionary atonement. Whether this way is a better way is beyond scope of this post. But for my part, it’s hard to understand why Christ would ask for the cup to be taken from him unless he believed it to be the cup of God’s wrath that he would drink to the bitter dregs for sinners like us.

March 26, 2018

Let Us Never Grow Weary of the Cross

It was one of the things I loved most about my previous church. And it’s one of the things I’m already seeing that I will love about my current church:

They love the most basic sermons the best.

I don’t mean “basic” as in “simplistic.” As far as I know, I’ve never been accused of dumbed-down messages. By “basic” I mean bread-and-butter sermons. Keeping the plain things plain, and keeping the main thing the main thing. I love that the people I serve love to hear the old, old story one more time. They’ll be interested in millennial views, but they’ll thrill to hear about the God who saves.

You’ve probably heard the quip that the first generation believes the gospel, the second generation assumes the gospel, and the third generation loses the gospel. That’s true, and sadly, it happens. But I think there’s another step in there somewhere. It’s called getting bored with the gospel. Maundy Thursday no longer moves us. Good Friday doesn’t feel that good. Easter isn’t a big deal. It’s just the same passages, the same services, and the same kind of sermons.

Beware when the cross and the empty tomb cannot compete with March Madness and The Masters.

Many of us will turn to the old familiar hymns this week. I hope we are paying attention to the words. We’ll sing of that sacred head now wounded and of surveying the wondrous cross. We’ll shout Hallelujah! to the man of sorrows. We’ll wonder again how can it be that I should gain? We’ll remember the one who was stricken, smitten, and afflicted. We’ll ask how our holy Jesus hast offended. And then two days later we’ll announced that Christ the Lord is risen today. What a privilege to rehearse the good news in song for yet another year.

Sometimes the people get bored, but too often the preacher gets bored first. Careful, pastor, this is not the week for trying new things and introducing new themes. It’s the week for celebrating old things that still have the power to make us new.

Let us not wander far from sin, salvation, and judgement. Let’s not strain to make ourselves relevant to the politics, the pop culture, or the presidential controversy of the day. Christ’s death and resurrection will be relevant on its own. The message of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John is still the message people need. They need to see the cross—who was hanging there, why he had to die, and why he could not stay dead.

Sin is worse than you think. The good news is better than you imagine. That’s what our people need to hear.

Jesus lived. Jesus died. Jesus lives again.

Christ arose. Christ reigns. Christ will return.

We have sinned. We will die. We can live forever.

Keep is simple. Play it straight. Preach Christ and him crucified.

As Christians, this is our Holy Week, and this is our Happy Week. Joy in suffering. Victory in defeat. From darkness into light. We must not shrink back from singing and sharing and savoring the whole counsel of God, and especially the gospel delivered to us as of first importance (1 Cor. 15:3). It is, after all, the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes (Rom. 1:16).

The gospel still saves. We have no reason to be ashamed of blood and wrath and death, for without them there can be no cleansing and forgiveness and life. Let us not tire of singing the same old songs. Let us not be bored in preaching the same good news. And let us never grow weary of the same rugged cross.

March 19, 2018

Theological Primer: Substance and Accidents

From time to time I make new entries into this continuing series called “Theological Primer.” The idea is to present important theological terms and concepts in around 500 words. Today we look at substance and accidents.

*****

If we want to make sense of the best Christian theologians from the patristic period, through Thomas Aquinas, through the period of Reformed Orthodoxy, and into the twentieth century, sooner or later we will need to understand the Aristotelian distinction between substance and accidents.

According to Aristotle’s logic, there is a basic distinction between the thing itself (substance) and what may be said incidentally about the thing (accidents). Substance is whatever exists in and of itself, whereas accidents are what modify substances. Accidents—which might better be called incidentals, so as not to be confused nowadays with our “oops” kind of accidents—bring change to the substance, without changing the kind of thing the substance is. So a dog is a substance, but brown or fluffy or big are accidents. A dog is a dog no matter its color or size, but for brown or fluffy or big to exist, they must adhere to something else. In simplest terms, we can think of accidents as giving to a substance its quality or quantity.

The distinction is an important part of the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. Catholic theologians relied on the familiar terms to explain how the bread and wine could still taste, touch, and smell like real bread and wine (accidents), even as the substance had been changed into the physical body and blood of Christ. Reformed theologians rejected the doctrine not only on the grounds that it is historically novel and exegetically fanciful, but also because it is logically untenable. For example, Bavinck, without rejecting the longstanding distinction, argued that in transubstantiation the accidents retain such bread and wine properties that (irrationally) they act more like substances (Reformed Dogmatics, 4.571).

More to the point, most Reformed theologians have readily embraced the terms substance and accidents, seeing the distinction as integral to a proper understanding of God himself. As a simple being, God is not a compound or made up of parts. God is whatever he has. He can be described using terms of quality or quantity, because that is how finite beings can comprehend an infinite God. But as pure being, God cannot be composed of substance and accidents, of matter and form, of potentiality and actuality, or of essence and existence (Reformed Dogmatics, 2.176).

As is often the case, Turretin parses the matter with precision, arguing that “No accident can be granted in God” because of divine simplicity (accidents imply that God is composed of parts), infinity (accidents would add to the substance some new quality), and immutability (accidents always allow for change). God is the Great I AM, the one who is that he is, the one whose essence and existence cannot be augmented by any further properties (Elenctic Theology, IV.1.4).

In other words, if God is whatever God has—that is, if every attribute of God is identical with his essence—then it does not make sense to say that God can undergo a change of any kind (atemporal or temporal, essential or nonessential). God possesses all of his attributes to the uttermost, in such a way that they can be identified with God himself. Consequently, God is only substance, because divinity, by definition, is that true being which can admit no accidents.

March 13, 2018

What I Learned on My Week Long Digital Fast

I just finished a week long digital fast. Parts of it were difficult, and other parts were surprisingly easy, but most of all it was refreshing to be away from my screens and away from the internet as much as possible.

As part of my pastoral ministry class at RTS I assigned a digital fast for all 30 students, and I told them that I would join them in the experience. To make even more people happy, I made my whole family join in the fast with us. While we weren’t able to completely detach from all digital technology, we did the best we could from March 4-11. These were the rules:

No smart phones for the week except for calls and texting. I also allowed the use of Google Maps and a weather app. But no games or other apps on the phone.

No television or movies.

Computer use was allowed for work purposes. We are too tied to our computers to feasibly require students (or professors!) to keep the computer closed all week.

No internet usage on the computer, unless absolutely required for work purposes. No games or streaming.

No social media whatsoever.

I allowed everyone (myself included) to check email only once a day (and no keeping it open all day as your one turn).

If a student felt like there were essential reasons to break one of these rules, they had to mark that down in a logbook and report it to me at the end of the week.

So how did I do?

I would give myself an A on the rules pertaining to television, movies, games, and social media. I didn’t turn on or check any of these things.

As for general internet usage, probably a B+. I didn’t go online intentionally, but I did follow a few links that were sent to me over email. I also needed to find some old blog posts for study purposes. I thought that was a legitimate use of the internet (more like a library than entertainment or distraction).

Limiting myself to one email check per day was challenging. I kept to the rule fastidiously most of the week, but there were a couple days where I needed (or I thought I needed) to keep up with some important emails going back and forth, and so I checked a few times, but still much less than my usual rate. Overall, maybe a B- in this category.

My kids did pretty well with the week considering I took away their phones and iPads and turned off the television. They didn’t complain (much). We did, however, allow a cheat or two for sick kids or for those who were babysitting their siblings.

For as much as I’m usually tied to my phone and email, I was really looking forward to the digital fast. I knew it would be good for and good for my family. I’m not ready to throw out all my technology (I’m blogging these reflections after all!), but there are a number of lessons I’m processing from the last week—not lessons that will be surprising to most people, but important nonetheless.

I didn’t miss social media at all. I thought I might, but instead it felt freeing to be away from Facebook and Twitter and the fever swamps of the blogosphere. I’m not going to quit social media, but hanging out there less sure seems like a good idea. I’ve thought for quite some time that scrolling through social media (especially Facebook and Twitter) has not made me happier or holier. Besides, it can be such a time waster. I found myself picking up a book to read or helping around the house in the little cracks of the day, instead of taking 10 minutes to scroll through the latest round of hot takes.

We have allowed our kids too much time on their devices. My wife and I are still trying to determine what some workable rules look like, but we know tighter time constraints are in order. It was great to see the kids work on a puzzle, take out board games, and call on each other to play, as opposed to vacating in front of their own screens. It was also nice to be free from constantly monitoring device usage and calling for their attention.

We are more dependent on our devices than we realize. During the week I’d find myself picking up the phone to look up some factoid or to search out an article or get more information about some famous person, and then I’d remember, “Oh right, the fast.” I’m used to having all the information in the world literally at my fingertips. I “fell behind” on the week’s news (as if any of us are “caught up”). I didn’t even realize we needed to change our clocks until someone not on the fast told me on Saturday.

We use our devices as treats throughout the day. I’m used to my phone or the television being my brain break after a day (or 20 minutes!) of hard work. I watch very little television—Jeopardy, sports, and that’s about it. But still, I did miss the availability of putting on a game in the background at night, or of watching March Madness in my hotel room at the end of a long day. What I didn’t miss was the constant distraction of looking to my phone every time my attention span wobbled.

We need better email habits. Or at least I do. On the good side, I generally respond to emails quickly and keep my (main) account at or near zero. On the bad side, the way I make this happen is by checking my email a bazillion times a day. Although it was hard to limit myself to one check a day (and I don’t think that’s workable in perpetuity), this approach certainly has its advantages. Because I could only check once, I made sure that one time would count. So I wasn’t about to check email waiting in line at the grocery store, or first thing in the morning, or in the five minutes between meetings. I checked when I knew I had at least 45 minutes to respond to as many emails as possible. This meant that I took care of everything I could on the spot. It also meant that once I was done, I was done. I didn’t feel the pressure to keep my inbox at zero. All the productivity books talk about limiting time spent on email. There’s nothing revolutionary here. But experiencing it for a week, I want to limit myself to a set number of checks each day, rather than being tethered to email constantly. I may miss some banter that would have been enjoyable, and I may be late to a few time-sensitive emails. But more than we realize, most emails can wait or plain old be ignored.

So in the end, my takeaway from the digital fast is simple: less is more. We all know that, but very few of us are willing to do it. I’m convinced almost all of us would be happier, healthier, holier, and more productive if we checked email less, checked social media less, turned on the television less, went to the movies less, picked up our phones less. To be sure, there is Christian liberty in all this, but on the other side of my fast I am more determined not to use to my liberty as a license for bad habits that don’t help me as a pastor, a husband, a father, or as a Christian pursing Christ.

March 2, 2018

The Fantasy of Addiction

Peter Hitchens, writing on the “Fantasy of Addiction” in the February issue of First Things:

But it makes little difference. The belief is implanted in the modern mind, taught to the young not by explanation, experiment, and example but by being repeatedly and universally assumed. First of all, it is conventional wisdom, built into thousands of sentences, newspaper articles, TV and radio programs, sermons, speeches, and private conversations. Secondly, it is what we desire. Which of us, indulging in some pleasure, is not secretly relieved to find that others are weaker than we are, have nastier and more selfish pleasures, and that these things are generally excused because of a vast, universal thing that we cannot control or influence? Indulgence, like misery, seeks company for reassurance. Unlike misery, it generally finds that company. Beliefs spread in this way cannot really be challenged. Jonathan Swift rightly observed that you cannot reason a man out of a position he was not reasoned into in the first place.

It was the triumph of the Christian religion that for many centuries it managed to become the unreasoning assumption of almost all, built into every spoken and written word, every song, and every building. It was the disaster of the Christian religion that it assumed this triumph would last forever and outlast everything, and so it was ill equipped to resist the challenge of a rival when it came, in this, the century of the self. The Christian religion had no idea that a new power, which I call selfism, would arise. And, having arisen, selfism has easily shouldered its rival aside. In free competition, how can a faith based upon self-restraint and patience compete with one that pardons, unconditionally and in advance, all the self-indulgences you can think of, and some you cannot? That is what the “addiction” argument is most fundamentally about, and why it is especially distressing to hear Christian voices accepting and promoting it, as if it were merciful to call a man a slave, and treat him as if he had no power to resist. The mass abandonment of cigarettes by a generation of educated people demonstrates that, given responsibility for their actions and blamed for their outcomes, huge numbers of people will give up a bad habit even if it is difficult. Where we have adopted the opposite attitude, and assured abusers that they are not answerable for their actions, we have seen other bad habits grow or remain as common as before. Heroin abuse has not been defeated, the abuse of prescription drugs grows all the time, and heavy drinking is a sad and spreading problem in Britain.

Most of the people who read what I have written here, if they even get the end, will be angry with me for expressing their own secret doubts, one of the cruelest things you can do to any fellow creature. For we all prefer the easy, comforting falsehood to the awkward truth. But at the same time, we all know exactly what we are doing, and seek with ever-greater zeal to conceal it from ourselves. Has it not been so since the beginning? And has not the greatest danger always been that those charged with the duty of preaching the steep and rugged pathway persuade themselves that weakness is compassion, and that sin can be cured at a clinic, or soothed with a pill? And so falsehood flourishes in great power, like the green bay tree.

March 1, 2018

Seven Reasons Prayer Meetings Fail

It wasn’t too long ago that most churches included a prayer meeting as a part of their weekly rhythm. Maybe this was Sunday night or Wednesday evening or early one morning before the sun came up.

While there is nothing in the Bible that says a church must have a stated weekly prayer meeting, there is plenty in the Bible that says Christians should regularly be praying together. So whether the “prayer meeting” is on the calendar each week or takes place every day across small groups, staff meetings, elder meetings, and other corporate gatherings, there ought to be many recurring opportunities for church members to pray with one another.

And yet, most of us struggle to pray. Often the corporate prayer meeting feels even harder than our private devotional time.

So why do prayer meetings fail? Let me suggest seven reasons.

We hardly take time to pray. I’ve been to hour-long “prayer meetings” where four hymns are sung, a 25-minute devotional is given, people share prayer requests at length, and the people pray together for barely 10 minutes. I’m sure we’ve all seen small groups that say they are devoted to prayer and then rush through a closing prayer in 30 seconds at the end of a busy evening. Even when we mean to be praying, we can spend a lot of time ramping up for prayer, giving instruction for prayer, and setting the stage for prayer, when many of those things could be done with adroit leadership during the prayer time itself.

The individual prayers are too long. If you are in a group with five other amazing prayer warriors, you may be able to get away with one long prayer after another. But most Christians struggle with long prayers—they struggle to pray long prayers, and they struggle to keep alert during long prayers. Prayer meetings get bogged down when everyone feels like they need to prepare a three-minute soliloquy. That’s why I’m always telling people in group prayer, “Don’t be afraid to pray one or two sentences.” Less is often more.

Too few people participate. When people pray long prayers, fewer people pray. This is not only a matter of simple math; it’s part of the human psyche. “If participation at the prayer meeting means I need to pray as long or as well as Mrs. McGillicudy,” we reason, “then I better just keep my mouth shut.” Keep things moving. Keep the prayers short and sweet. People will stay awake, and more people will pray.

No one has prepared to lead. In my experience, this is the biggest practical deterrent to corporate prayer. True, it’s possible to have a dynamic prayer meeting without any planning on at all. History is full of examples of Christians who got together on the spur of the moment and rattled the gates of hell with their prayers. But in most church at most times and in most places, we need help to pray well. That means someone has thought through what we are praying about. Someone is ready to steer the group through different topics. Someone is ready to call out a new topic or take folks to a new passage. It’s amazing how twenty minutes of structure-less praying can feel like forever, while an hour of carefully planned prayer can go by in a flash.

There is no variety in prayer. Too many prayer meetings spend half the time in taking prayer requests and then half the time in unstructured prayer for those requests. There is nothing wrong with that design. I’ve used it many times. But prayer will become dull and dreary if this is all we do. We should be using Scripture, songs, corporate readings, prayer books, old liturgies, and other forms in our prayer. Mix it up. Learn from the saints who have gone before us.

We don’t stick to the allotted time. Again, I’m sure some Christians love to pray for hours and hours without structure or without an end in sight. And yet, if we’re honest, that’s not where most of us are, especially in Western culture. When I introduced a 7 a.m. prayer meeting years ago, I laid down clear ground rules. We would start promptly at 7. No one would bring food or coffee. The leader would take no more than five minutes to introduce our prayer time. Then we would pray and end at 7:30 on the button. Does this work in every culture? Maybe not. But it helped our folks know what to expect and know that they could get home to the kids or get to work on time.

We forget that we are praying. It happens to me all the time. I’m listening to prayers, or praying myself, and suddenly realize, “We are speaking to the God of the universe.” If we’re not careful, corporate prayer become an exercise in giving short religious speeches. We forget that we are talking to someone—and not just to someone, but to God Almighty, our holy and loving heavenly Father. God loves it when we pray, and he listens when we pray. The Spirit helps us. The Son intercedes for us. Don’t forget what you are doing when you pray.

February 26, 2018

Book Briefs

It’s always nice to sit down and write up my Book Briefs post, because it means I’ve been reading! Maybe you’ll find something helpful in this list of recent reads.

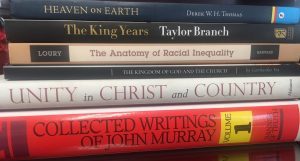

Derek W.H. Thomas, Heaven on Earth: What the Bible Teaches about Life to Come (Christian Focus, 2018). What is heaven like? What happens when I die? What takes places at the end of human history? Derek makes for a terrific guide in examining these questions. A quick and edifying read.

Taylor Branch, The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement (Simon and Schuster, 2013). Branch’s trilogy on American in the King Years is magisterial. It’s also massive. Enter this 200 page paperback which is a Reader’s Digest version of the larger three volumes. You’ll find excerpts (with some new material) on all the major events, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to Bloody Sunday to the March on Washington to King’s assassination in Memphis. Not a bad place to start if you want to brush up on your history before the MLK events this spring.

Glenn Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality (Harvard University Press, 2002). This book–which Loury calls “a meditation on the problem of racial inequality in the United States, focusing specifically on the case of African Americans”–emerged from the W.E.B. Du Bois Lectures delivered at Harvard in 2000. Although the book is need of an editor and suffers from opaque academic jargon, the three axioms Loury sets out to defend are well worth considering. Loury argues for the explanatory power of “constructivism” (race is a social convention with no justification in biological taxonomy), “anti-essentialism” (the social disadvantage of African Americans is not owing to differing innate human capacities), and “ingrained racial stigma” (given our national history, the otherness of Blacks is deeply entrenched and exercises a profound negative affect on African Americans). On this last point, Loury argues that while we must address how people are treated (discrimination), the more persistent problem has to do with who Blacks are understood to be (stigma).

Geerhardus Vos, The Teaching of Jesus Concerning the Kingdom of God and the Church (Fontes Press, 2017). At less than 100 pages, this is a great introduction not only to Vos but to the doctrine of the Kingdom. Vos is especially helpful in explaining the objective nature of the kingdom and its relationship to the church. The new introduction by Danny Olinger is also quite useful.

William Harrison Taylor, Unity in Christ and Country: American Presbyterians in the Revolutionary Era, 1758-1801 (University of Alabama Press, 2017). In this book, Taylor (an associate professor of history at Alabama State University) argues that Presbyterians in America had an interdenominational bent that began to fall apart on the other side of the Revolution. While I wasn’t convinced by every argument in the book, the overarching case is certainly a strong one: colonial Presbyterians dreamed of a unified Christian nation that would benefit America and the world.

John Murray, Collected Writings of John Murray, Volume 1: The Claims of Truth (Banner of Truth, 1976). In this collection of lectures, addresses, and sermons, Murray shows himself to be that rarest of birds: a first rate academic who could communicate clearly. These 49 chapters on everything from Christology to the Sabbath to evangelism to Calvin to war to Christian education can be read profitably as history, as theology, or as devotional edification.