Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 13

January 16, 2019

16 Truths About Digital Time and Real Friends

In his new book, Them: Why We Hate Each Other and How to Heal, Ben Sasse has a terrific chapter on setting tech limits. “At our house,” he writes, “after a healthy wrestling match about the dangerous ways social media tries to pull us away from the communities we care about the most, we put a list of 16 truths up on our refrigerator.” Sasse describes the list as “neither complete nor fancy,” but a helpful way for his family to think about digital communities versus real ones. I found this list full of easily forgotten common sense and good wisdom.

1. Your thousandth social media friend won’t make you any happier. Your fourth real real friend will.

2. Uninterrupted time is life’s most valuable limited resource.

3. Most news isn’t news.

4. Envy isn’t good therapy. Rage isn’t good therapy. Working out is good therapy.

5. Do something now you’ll want to talk about at the dinner table tonight.

6. Political addicts are weird. (And there aren’t that many of them. They’re just loud.)

7A. I’d rather be with the people I’m with right now than with the people I’m not with.

7B. If #7A isn’t true, then spend more time with the right people.

8. Develop the right addictions. (Another word for addictions is habits. Habits determine character.)

9. Not every bad thing in the world requires a response from you.

10. Not every mean thing said to you requires you to acknowledge it.

11. You’re not omniscient. Don’t assume your bubble of information is the whole story.

12. You’re not omnipotent. Taking in bad news you can’t do anything about doesn’t help anyone.

13. Sports Twitter is infinitely better than political Twitter.

14. Lots more social media is fake bots than social media companies admit.

15. The little old lady on your block probably has an important unmet need today.

16. Social media isn’t great for deep stuff. It’s great for humor. Let’s be known as a family that laughs hard. (p. 199)

Good stuff. Might look nice up on your refrigerator. Mine too.

January 8, 2019

Systematic Theology Review

Over the years I’ve been asked from time to time what systematic theology I recommend. That short answer is: it depends. It depends on who is asking the question (college student? seminary student? lay leader? pastor?), and it depends on what the person wants out of a systematic theology (an introduction? a reference book? an influential classic?).

The good news is there are plenty of good resources that have served the church well and will strengthen your understanding of the faith. With only 5 to 10 minutes a day, you could read through an entire systematic theology in the course of a year.

Below you’ll find my brief evaluation of several systematic theologies, with the reading level noted for each (Beginner, Medium, Hard). I’ll start with my three favorites and then move on to the others in a few different categories.

In making this list, I’ve limited myself to systematic theologies that (1) I have read through or have used before, (2) are readily available, and (3) are committed to the inerrancy of Scripture. This means, almost everything on my list is Reformed (point #1), are in print and available for easy purchase online (point #2), and are helpful and edifying (point #3).

My Top Three

John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559). Historians might argue it’s not exactly a systematic theology, but it’s theology at its best. It’s the one I read first and have read most. Much more readable than you might think and filled with beautiful passages that will inspire as well as inform. Level: Medium (two volumes)

Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology (1679-1685). This was the textbook at Old Princeton until Charles Hodge wrote his own. It’s hard to overstate the influence Turretin has had on the development and transmission of Reformed theology. Some of the debates will seem overly philosophical and arcane. But for comprehensiveness and careful delineation of categories, you will not find anything better. Level: Hard (three volumes)

Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (1938). A model of order, precision, and (relative) brevity. Yes, it’s often a distillation of Bavinck, but you will not find a better one-volume systematic theology in the Reformed tradition. I re-read Berkhof as much anything else on this list. Level: Medium (one volume)

Classics

Petrus Van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology (1698). With only the first of seven volumes published, I’m not able to give a proper assessment of this massive work. But we know that Jonathan Edwards considered it superior to Turretin and the best book on divinity besides the Bible. Mastricht treats each topic exegetically, dogmatically, elenctically (polemically), and practically. The work is both highly technical and rigorously doxological, with a complex outline, moments of eloquence, and (at times) very long lists. Level: Hard (one volume currently, with six others planned)

Willhelmus à Brakel, The Christian’s Reasonable Service (1700). This four-volume work deserves more attention than it normally receives, for it combines the mature fruit of Protestant Scholasticism with the rich piety of the Dutch Second Reformation. Unique among systematic theologies, the last two volumes are almost entirely devoted to sanctification, covering topics like contentment, self-denial, patience, and prayer. Level: Medium (four volumes)

Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology (1871-1873). It’s unfortunate that Hodge has been caricatured as an unfeeling “nothing but the facts” theologian, because personally he was warm, and pastoral and theologically he is never dry and dusty (save for the untranslated Latin paragraphs!). I’ve always found Hodge helpful on questions of reason and revelation. Level: Medium (three volumes)

Geerhardus Vos, Reformed Dogmatics (1896). Just published for the first time in English, this work represents theological exploration from a gifted young man who would later make his mark in the field of biblical theology (as opposed to systematics). Vos employs a catechetical question-and-answer approach, making his theology read like lecture notes more than continuous prose (a feature that some will appreciate and others will not). Level: Medium (five volumes)

Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics (1906-1911). If you think Bavinck belongs in the top three, I won’t complain. Bavinck is a brilliant exegete, historian, philosopher, and theologian. Berkhof is basically a summary of Bavinck, so if you want to go deeper and wider and fuller, you need these four volumes. For the best multi-volume Reformed dogmatics, I’d take Turretin, Bavinck, and à Brakel. Also check out Bavinck’s smaller work Our Reasonable Faith. Level: Medium (four volumes)

Historical Treatment

Richard Muller, Post-Reformed Reformed Dogmatics (2003). No one know the theology of the Reformed Orthodox period better than Muller. His command of the original sources (usually in Latin) is amazing. Not for the faint of heart, but worth having and consulting often. Level: Hard (four volumes)

Joel Beeke and Mark Jones, Puritan Theology (2012). A tremendous achievement. Beeke and Jones go through the traditional loci explaining what major Puritan thinkers taught on each topic. Harder to use than a traditional systematic theology, but still useful. Beeke and Jones know their stuff. Level: Hard (one volume)

Contemporary Works

Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology (1994). An unlikely bestseller, but if you find a college student reading systematic theology for fun, he’s probably reading Grudem. As a Presbyterian appreciative of classic theism, I don’t agree with all of Grudem’s conclusions, but he’s hard to beat for clarity, accessibility, and readability. You may also want to use Bible Doctrine or Christian Beliefs. Level: Beginner (one volume)

Michael Horton, The Christian Faith (2011). While the organization and layout are not as user-friendly as Grudem, Horton is a much more sophisticated theologian. Horton is especially good if you want a reliable contemporary writer who is conversant with the history of theology and with the best theologians from other traditions. See also Horton’s shorter Pilgrim Theology and Core Christianity. Level: Medium (one volume)

Gerald Bray, God Is Love: A Biblical and Systematic Theology (2012). Bray’s approach is unique in that (1) he has organized an entire systematic theology around the love of God and (2) he cites nothing but the Bible. Whether this is the book’s greatest strength or its Achilles’ heel depends on what you are hoping for in a systematic theology. One can see the influence of Anglicanism’s “basic” or “mere” Christianity. Level: Beginner (one volume)

John Frame, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief (2013). Like all of Frame’s other works, the strength of this one is that it is biblical and readable. I wish Frame were more in line with classic Reformed theology on certain points, but I appreciate Frame’s eagerness to be practical and scriptural. A final assessment of the book likely depends on whether you find tri-perspectivalism incredibly helpful or a bit tenuous. Level: Beginner (one volume)

R. C. Sproul, Everyone’s a Theologian (2014). This is the book I recommend to Christians who are completely new to systematic theology. It’s a great, relatively brief, introductory volume with Sproul’s typical energy and clarity. Level: Beginner (one volume)

Douglas Kelly, Systematic Theology (2008, 2014). Centered on the doctrine of the Trinity, Kelly weaves together an impressive array of theologians from the early church through the medieval period and the Reformation down to the present. The plethora of block quotes, not too mention Kelly’s own brilliance, make for hard reading at times, but there is plenty here to repay serious reflection. Level: Hard (two volumes)

Coming Soon: Joel Beeke and Paul Smalley, Reformed Systematic Theology: Volume One: Revelation and God (March 2019) (the first volume of a multi-volume work) and Robert Letham, Systematic Theology (November 2019). These promise to be strong additions to the stable of Reformed theologies.

Other Resources

Anthony Hoekema, Created in God’s Image (1986), Saved by Grace (1989), The Bible and the Future (1979). I’ve always found the structure in these volumes intuitive and the exegesis particularly careful. Excellent and easy to use in pieces if you don’t want to read the whole thing. Level: Medium

Contours of Christian Theology (1993-2002). This series, edited by Gerald Bray, is one of the best things IVP ever published. Each volume tackles a single loci in 250 to 300 pages: The Doctrine of God (Gerald Bray), The Work of Christ (Robert Letham), The Providence of God (Paul Helm), The Doctrine of Humanity (Charles Sherlock), The Holy Spirit (Sinclair Ferguson), The Person of Christ (Donald MacLeod), The Revelation of God (Peter Jensen), The Church (Edmund Clowney). For my money, the Letham and Ferguson volumes are the strongest and Sherlock is the weakest. Level: Medium

The ESV Study Bible has significant articles on all the major loci, while the new ESV Systematic Theology Study Bible links up theological reflection with the text of Scripture. Level: Beginner

December 31, 2018

Top Ten Blog Posts of 2018

I like lists, and year-end lists in particular are always fun. So here’s a list of my top ten most viewed blog posts from the past year. Actually, several of the top posts in the past year were written in previous years. I’ll pull those out and include them at the end.

1. Enneagram: The Road Back to You, Or to Somewhere Else? If the Enneagram were another version of What Color Is Your Parachute? or Strengths Finder, that would be fine. But it has been, from its inception (whenever that was), infused with spiritual significance. And therein lies the danger.

2. Racial Reconciliation: What We (Mostly, Almost) All Agree On, and What We (Likely) Still Don’t Agree On Some our disagreements are biblical and theological, while others are matters of history or policy, and still others require a good deal of expertise on sociology, law, economics, and criminology. By more carefully isolating our real disagreements we will be better equipped to talk responsibly, listen respectfully, find common ground, and move in the direction of possible solutions.

3. Is Social Justice a Gospel Issue? As in so many controversies, we must be quicker to define our terms than to define our opponents. Depending on our definitions, social justice and the gospel may be miles apart, or they may be as close as loving God by obeying his commands (John 14:15).

4. Seven Reasons Prayer Meetings Fail While there is nothing in the Bible that says a church must have a stated weekly prayer meeting, there is plenty in the Bible that says Christians should regularly be praying together. And yet, most of us struggle to pray. Often the corporate prayer meeting feels even harder than our private devotional time.

5. Are We Really in Danger of Making an Idol of the Family? The conjugal family—one man and one woman whose covenant union produces offspring—is profoundly good, a necessary and foundational element of God’s creational design. But it is not ultimate.

6. Words, Labels, and ‘Sexual Minorities’ I hope we in the PCA, and in the broader church, will pay more careful attention to the words and terms we use in these controversial matters. Once the labels stick, they become sticky indeed.

7. The Missing Word in Our Modern Gospel The gospel is more than positive self-talk, and the gospel Jesus and the apostles preached was more than a warm, “don’t let anybody tell you you’re not special” bear hug. There’s a word missing from the presentation of our modern gospel. It’s the word repent.

8. Marcion and Getting Unhitched from the Old Testament The idea of recasting Christianity for a new day—in softer, gentler hues, more focused on the life of Jesus instead of the wrath-satisfying death of Jesus—is always popular. Some errors never quite die, and some new things are not that new.

9. Why Pastors Should Consider Preaching (At Least) Five Minutes Shorter While guest preaching in a church several years ago I asked the senior pastor how long I should preach. He replied, “Five minutes shorter than you think.” His advice was tongue-in-cheek. But it was also partly serious. He went on to add that he’d rarely heard a sermon that couldn’t have been better by being five minutes shorter.

10. What Is My Calling? (And Is That Even a Good Question?) If “calling” involves waiting for promptings, listening for still small voices, and attaching divine authority to our vocational decisions, then we’d be better off dropping the language and labor less mysteriously to help each other grow in wisdom.

Actually…

The four posts below were among the most viewed in the last year, but they were not posted in 2018.

What Does the Bible Say about Transgenderism? (2016)

Three Surprising Ways to Grieve the Holy Spirit (2013)

Protestant and Catholic: What’s the Difference? (2017)

A Brief Defense of Infant Baptism (2015)

Perhaps the fact that each of these posts are explicitly theological in nature says something important about what kind of posts can outlive their culture moment.

December 23, 2018

Merry Christmas, Pastor, and Don’t Lose Heart

Merry Christmas, pastor.

I know you are getting ready for a busy day. If you’re like me, you’re just coming off a full Sunday and still need to finish your Christmas Eve sermon before the sun goes down and the candles get lit. I’m sure you’ve had a full week, a full month, and a full year. I hope you get some time off in the next week.

I also know that as you think back on another year—and already have to be cranked up for the new one—it’s tempting to wonder if your ministry is making any difference. I know the temptation well. It doesn’t matter the size of your church, the length of your ministry, or the number of followers on social media, almost every pastor has weeks (months? seasons? years?) where he questions the effectiveness of his preaching, his praying, his leading, and just about everything else he’s poured his heart and soul into.

Don’t lose heart.

I just finished the grading for my pastoral ministry class. The final assignment was to write a paper on two pastors whose examples they want to emulate and whose priorities have shaped their own. The catch: one of the pastors must already be in glory, and one must still be alive.

On the dead side, the students wrote about the men you’d expect RTS students to write about. I’ve read papers on Athanasius, Baxter, Bonhoeffer, Bucer, Calvin, Chrysostom, Edwards, Lloyd-Jones, Luther, and Spurgeon (among others). We have much to learn from all these men and many reasons to thank God for them.

I’ve also read papers on Rob and Josh and Tom and David and Ben and Jerry and Mike—men you may never have heard of and may never know. And yet, my students know them, because these have been their pastors—some fathers, some grandfathers, some campus workers, some youth pastors, some associate pastors, but all pastors making a difference in the lives of their people. The students see they way the lead, they see their humility, they see their hospital visits, they see their suffering, they see their labors in the study, and yes, they see their weaknesses and imperfections too. These pastors have shown my students how to live and love in light of God’s Word. Above all, they have shown their people Christ.

And I’m the beneficiary, by having them in my class. And future (or current) congregations and future (or current spouses and children) are the beneficiaries too. “You then, my child, be strengthened by the grace that is in Christ Jesus, and what you have heard from me in the present of many witnesses entrust to faithful men, who will be able to teach others also” (2 Tim. 2:1-2). This has been happening for 2,000 years. It’s happening in the world right now. Be encouraged, brother pastor, it’s almost certainly happening in your ministry.

The fruit can be hard to see at times, and “you’re making a difference in my life” may not be verbalized as often as we would like. Most weeks it’s more of the same. Another meeting, another prayer, another email, another visit, another sermon. In God’s grace, however, all the “anothers” add up to something. Usually more than we know. No matter who hears about it. Or whether we can even see it.

Keep fighting the good fight, reverend. Keep your hand to the plow. Keep sowing that seed. Don’t lose heart.

And Merry Christmas.

Merry Christmas Pastor, And Don’t Lose Heart

Merry Christmas pastor.

I know you are getting ready for a busy day. If you’re like me, you’re just coming off a very full Sunday and still need to finish your Christmas Eve sermon before the sun goes down and the candles get lit. I’m sure you’ve had a full week, a full month, and a full year. I hope you get some time off in the next week.

I also know that as you think back on another year–and already have to be cranked up for the new one–it’s tempting to wonder if your ministry is making any difference. I know the temptation well. It doesn’t matter the size of your church, the length of your ministry, or the number of followers on social media, almost every pastor has weeks (months? seasons? years?) where he questions the effectiveness of his preaching, his praying, his leading, and just about everything else he’s poured his heart and soul into.

Don’t lose heart.

I just finished the grading for my pastoral ministry class. The final assignment was to write a paper on two pastors whose examples they want to emulate and whose priorities have shaped their own. The catch: one of the pastors must already be in glory and one must still be alive.

On the dead side, the students wrote about the men you’d expect RTS students to write about. I’ve read papers on Athanasius, Baxter, Bonhoeffer, Bucer, Calvin, Chrysostom, Edwards, Lloyd-Jones, Luther, and Spurgeon (among others). We have much to learn from all these men and many reasons to thank God for them.

I’ve also read papers on Rob and Josh and Tom and David and Ben and Jerry and Mike–men you may never have heard of and may never know. And yet, my students know them, because these have been their pastors–some fathers, some grandfathers, some campus workers, some youth pastors, some associate pastors, but all pastors making a difference in the lives of their people. The students see they way the lead, they see their humility, they see their hospital visits, they see their suffering, they see their labors in the study, and yes, they see their weaknesses and imperfections too. These pastors have shown my students how to live and love in light of God’s word. Above all, they have shown their people Christ.

And I’m the beneficiary, by having them in my class. And future (or current) congregations and future (or current spouses and children) are the beneficiaries too. “You then, my child, be strengthened by the grace that is in Christ Jesus, and what you have heard from me in the present of many witnesses entrust to faithful men, who will be able to teach others also” (2 Tim. 2:1-2). This has been happening for 2,000 years. It’s happening in the world right now. Be encouraged, brother pastor, it’s almost certainly happening in your ministry.

The fruit can be hard to see at times, and “you’re making a difference in my life” may not be verbalized as often as we would like. Most weeks it’s more of the same. Another meeting, another prayer, another email, another visit, another sermon. In God’s grace, however, all the “anothers” add up to something. Usually more than we know. No matter who hears about it. Or whether we can even see it.

Keep fighting the good fight reverend. Keep your hand to the plow. Keep sowing that seed. Don’t lose heart.

And Merry Christmas.

December 18, 2018

Theological Primer: Hypostatic Union

From time to time I make new entries into this continuing series called “Theological Primer.” The idea is to present big theological concepts in around 500 words. Today we look at the hypostatic union.

*****

In simplest terms, the hypostatic union is a reference to Jesus Christ as both God and man, fully divine and fully human. Hypostasis is the Greek word for subsistence (think: individual existence). The hypostatic union, therefore, is the technical term for the unipersonality of Christ, whereby in the incarnation the Son of God was constituted a complex person with both a human and a divine nature.

For a concise and careful definition of the hypostatic union, the Chalcedonian Definition (451 A.D.) is still unsurpassed.

Therefore, following the holy fathers, we all with one accord teach men to acknowledge one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, at once complete in Godhead and complete in manhood, truly God and truly man, consisting also of a reasonable soul and body; of one substance with the Father as regards his Godhead, and at the same time of one substance with us as regards his manhood; like us in all respects, apart from sin; as regards his Godhead, begotten of the Father before the ages, but yet as regards his manhood begotten, for us men and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the God-bearer; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation; the distinction of natures being in no way annulled by the union, but rather the characteristics of each nature being preserved and coming together to form one person and subsistence, not as parted or separated into two persons, but one and the same Son and Only-begotten God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ; even as the prophets from earliest times spoke of him, and our Lord Jesus Christ himself taught us, and the creed of the fathers has handed down to us.

At the heart of this definition are the four negative statements I’ve italicized above.

Without confusion: The Lord Jesus Christ is not what you get when you mix blue and yellow together and end up with green. He’s not a tertium quid (a third thing), the result of mixing a divine and human nature.

Without change: In assuming human flesh, the Logos did not cease to be what he had always been. The incarnation affected no substantial change in the divine Son.

Without division: The two natures of Christ do not represent a split in the divine Person. Jesus Christ is not half God and half man.

Without separation: The union of the human and divine in the person of Jesus Christ is a real, organic union, not simply a moral sympathy or relational partnership.

This may seem like needless theological wrangling, but Chalcedon’s careful definition is meant to preserve the biblical teaching that (1) the divine nature was united, in the person of the Son, with a human nature (John 1:14; Rom. 8:3; 1 Tim. 3:16; Heb. 2:11-14) and (2) the two natures are united in only one divine Person (Rom. 1:3-4; Gal. 4:4-5; Phil. 2:6-11). As Chalcedon puts it, the characteristics of each nature are preserved–in no way annulled by the union–even as they come together in one person (prospon) and one subsistence (hypostasis).

December 13, 2018

Top Ten Books of 2018

First, my usual disclaimer and explanation.

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of Christian books published each year, let alone every interesting book published in 2018. There are plenty of worthy titles that I am not able to read (and lots I never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year.

When I say “best” I have several questions in mind:

• Was this book well written and enjoyable to read?

• Did I find it personally challenging, illuminating, edifying, or entertaining?

• Is it a book I am likely to reread or consult again?

• Do I see myself recommending this book to others?

Undoubtedly, the “best” books reflect my interests. This doesn’t mean I agree with every point in these books, but it does mean I found them helpful and insightful.

10. Charles Malcolm Wingard. Help for the New Pastor: Practical Advice for Your First Year of Ministry (P&R Publishing). The book is what it says it is: a great resource of practical advice for pastors. I’d say especially the new pastor, but not exclusively. Every page has helpful wisdom on various aspects of pastoral ministry–from visitation to administration to preaching to counseling to leading in worship.

10. Charles Malcolm Wingard. Help for the New Pastor: Practical Advice for Your First Year of Ministry (P&R Publishing). The book is what it says it is: a great resource of practical advice for pastors. I’d say especially the new pastor, but not exclusively. Every page has helpful wisdom on various aspects of pastoral ministry–from visitation to administration to preaching to counseling to leading in worship.

9. Jonah Goldberg. Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics is Destroying American Democracy (Crown Forum). In some ways, a deeply flawed book in that Goldberg–a noted conservative author and secular Jew–removes God from the equation in the very first sentence. And yet, Goldberg is surely right to warn us that we have grossly overlooked, and are in danger of losing, the “Miracle” that is modern freedom and prosperity.

9. Jonah Goldberg. Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics is Destroying American Democracy (Crown Forum). In some ways, a deeply flawed book in that Goldberg–a noted conservative author and secular Jew–removes God from the equation in the very first sentence. And yet, Goldberg is surely right to warn us that we have grossly overlooked, and are in danger of losing, the “Miracle” that is modern freedom and prosperity.

8. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (Penguin Press). Like Goldberg, the authors here do not write with a Christian understanding of creation, anthropology, or how people change (so, for example, I don’t think cognitive behavioral therapy is the answer to what ails us). But Lukianoff and Haidt have put their finger on something important, especially in Part I where they expose the untruth of fragility (what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker), the untruth of emotional reasoning (always trust your feelings), and the untruth of us versus them (life is a battle between good people and evil people).

8. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (Penguin Press). Like Goldberg, the authors here do not write with a Christian understanding of creation, anthropology, or how people change (so, for example, I don’t think cognitive behavioral therapy is the answer to what ails us). But Lukianoff and Haidt have put their finger on something important, especially in Part I where they expose the untruth of fragility (what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker), the untruth of emotional reasoning (always trust your feelings), and the untruth of us versus them (life is a battle between good people and evil people).

7. Jonathan Leeman. How the Nations Rage: Rethinking Faith and Politics in a Divided Age (Thomas Nelson). This topic—the intersection of faith and politics—is one Jonathan knows a lot about, from his years ministering in D.C. to his doctoral work on politics and ecclesiology. Jonathan cuts through a lot of fuzzy thinking (on both sides of the political divide) and helps us see what is black and white and what is gray.

7. Jonathan Leeman. How the Nations Rage: Rethinking Faith and Politics in a Divided Age (Thomas Nelson). This topic—the intersection of faith and politics—is one Jonathan knows a lot about, from his years ministering in D.C. to his doctoral work on politics and ecclesiology. Jonathan cuts through a lot of fuzzy thinking (on both sides of the political divide) and helps us see what is black and white and what is gray.

6. Greg Easterbrook. It’s Better than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear (Public Affairs). Several books on this top ten list examine what’s wrong with the world and with America in particular. And there’s a lot to say on both fronts. But Easterbrook reminds us that while specific individuals, industries, and segments of societies have seen their lot in life decline, on a global scale life has gotten massively better over the past 50 years. We have more food from fewer animals and less land than ever before. People live longer than ever before. More people have been lifted out of poverty than ever before. Violence and warfare are down. Dictators are in decline. Pollution is less. Technology has made us safer. And the list goes on. Not the last word on the state of the planet, but an important word.

6. Greg Easterbrook. It’s Better than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear (Public Affairs). Several books on this top ten list examine what’s wrong with the world and with America in particular. And there’s a lot to say on both fronts. But Easterbrook reminds us that while specific individuals, industries, and segments of societies have seen their lot in life decline, on a global scale life has gotten massively better over the past 50 years. We have more food from fewer animals and less land than ever before. People live longer than ever before. More people have been lifted out of poverty than ever before. Violence and warfare are down. Dictators are in decline. Pollution is less. Technology has made us safer. And the list goes on. Not the last word on the state of the planet, but an important word.

5. Ben Sasse. Them: Why We Hate Each Other–and How to Heal (St. Martin’s Press). The title is a little misleading. While political polarization is an important theme, the book is really about healthy people leading healthy families that build healthy communities that make up a healthy nation. Sasse–the junior senator from Nebraska–is refreshingly down to earth, practical, self-aware, unimpressed with himself, and focused on “the habits of the heart and mind that make us neighbors and friends.” Not what we’ve come to expect from our elected officials.

5. Ben Sasse. Them: Why We Hate Each Other–and How to Heal (St. Martin’s Press). The title is a little misleading. While political polarization is an important theme, the book is really about healthy people leading healthy families that build healthy communities that make up a healthy nation. Sasse–the junior senator from Nebraska–is refreshingly down to earth, practical, self-aware, unimpressed with himself, and focused on “the habits of the heart and mind that make us neighbors and friends.” Not what we’ve come to expect from our elected officials.

4. Alex Hutchinson, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance (William Morrow). With Breaking2—the 2017 Nike-led project to run a sub-two hour marathon—as his backdrop, Hutchinson (a runner, columnist, researcher, and Cambridge PhD) explores the limits of athletic achievement and human endurance. This isn’t a training volume with secrets for getting a PR in your next race. Instead, it’s a journalistic examination of the different theories, studies, stories, and scholars trying to answer the simple question: what makes people keep going and what makes them stop? To that end, Hutchinson has chapters on muscles, heat, oxygen, thirst, fuel, and belief. His conclusion? We don’t finally know what makes people push through pain, but there is at least as much brain and belief involved as body and brawn.

4. Alex Hutchinson, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance (William Morrow). With Breaking2—the 2017 Nike-led project to run a sub-two hour marathon—as his backdrop, Hutchinson (a runner, columnist, researcher, and Cambridge PhD) explores the limits of athletic achievement and human endurance. This isn’t a training volume with secrets for getting a PR in your next race. Instead, it’s a journalistic examination of the different theories, studies, stories, and scholars trying to answer the simple question: what makes people keep going and what makes them stop? To that end, Hutchinson has chapters on muscles, heat, oxygen, thirst, fuel, and belief. His conclusion? We don’t finally know what makes people push through pain, but there is at least as much brain and belief involved as body and brawn.

3. D. Bruce Hindmarsh. The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism: True Religion in a Modern World (Oxford). In this important new work on evangelical devotion, Hindmarsh, a top flight historian and professor at Regent College, focuses on Edwards, Whitefield, and the Wesleys, but goes far beyond them in his analysis. Without discounting doctrinal continuity with the past, Hindmarsh argues that evangelical devotional ideas and practices were innovative, rooted in antecedent spiritual traditions, but new in their language and eclecticism.

3. D. Bruce Hindmarsh. The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism: True Religion in a Modern World (Oxford). In this important new work on evangelical devotion, Hindmarsh, a top flight historian and professor at Regent College, focuses on Edwards, Whitefield, and the Wesleys, but goes far beyond them in his analysis. Without discounting doctrinal continuity with the past, Hindmarsh argues that evangelical devotional ideas and practices were innovative, rooted in antecedent spiritual traditions, but new in their language and eclecticism.

2. Lewis Allen. The Preacher’s Catechism (Crossway). I’m always thankful for books that simultaneously convict and encourage. Using the Westminster Shorter Catechism as his inspiration and (loose) guide, Allen goes through 43 questions and answers designed to remind the busy/distracted/discouraged/puffed-up/cast-down preacher what really matters (and what doesn’t) in a life of faithful ministry. A Puritan throwback.

2. Lewis Allen. The Preacher’s Catechism (Crossway). I’m always thankful for books that simultaneously convict and encourage. Using the Westminster Shorter Catechism as his inspiration and (loose) guide, Allen goes through 43 questions and answers designed to remind the busy/distracted/discouraged/puffed-up/cast-down preacher what really matters (and what doesn’t) in a life of faithful ministry. A Puritan throwback.

1. Jonathan Gibson and Mark Earngey (eds). Reformation Worship: Liturgies from the Past for the Present (New Growth Press). My top book from 2018 is likely to be the least purchased and least read of all the books on this list. And at nearly 700 pages, it’s also the biggest of the books here. But that’s part of what makes the book so valuable. Few people will read straight through, cover to cover, a collection of Reformation-era liturgies (I didn’t). But the sheer size of this volume tells us something important. Namely, the Reformers thought a lot about worship. It was essential to their Reformation project, which makes our relative indifference to the forms and flow of worship all the more surprising (and scandalous). Every Reformed pastor and worship leader with a book budget should have this on their shelves.

1. Jonathan Gibson and Mark Earngey (eds). Reformation Worship: Liturgies from the Past for the Present (New Growth Press). My top book from 2018 is likely to be the least purchased and least read of all the books on this list. And at nearly 700 pages, it’s also the biggest of the books here. But that’s part of what makes the book so valuable. Few people will read straight through, cover to cover, a collection of Reformation-era liturgies (I didn’t). But the sheer size of this volume tells us something important. Namely, the Reformers thought a lot about worship. It was essential to their Reformation project, which makes our relative indifference to the forms and flow of worship all the more surprising (and scandalous). Every Reformed pastor and worship leader with a book budget should have this on their shelves.

November 26, 2018

Book Briefs

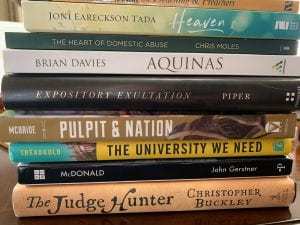

It’s been a long time since I’ve done a book briefs blog. So here’s a quick rundown on the stack I’ve been accumulating over the past few months.

Herman Bavinck on Preaching and Preachers, translated and edited by James P. Eglinton (Hendrickson, 2017). Most people know Bavinck as a great Reformed dogmatician. Here we see a different side of the Dutch scholar and churchman. Bavinck’s remarks on the “art and science” of preaching are well worth reading, as is the accompanying sermon and the fascinating excerpt on “Preaching in America.”

Joni Eareckson Tada, Heaven: Your Real Home . . . from a Higher Perspective, expanded edition (Zondervan, 2018). There is a lot to find in this book—a lot of Scripture, a number of great stories, a series of prayers, and a host of important insights. But what I found above all else was hope. I was struck time and again by how much joy Joni has invested in heaven—and how much I ought to have invested in heaven. This is a book for people who are ready to take heaven seriously. I was encouraged, rebuked, and comforted all at the same time.

Chris Moles, The Heart of Domestic Abuse: Gospel Solutions for Men Who Use Control and Violence in the Home (Focus Publishing, 2015). Chris Moles is a pastor, a certified counselor with ACBC, and a leading expert on domestic abuse in the church. Pastors and churches wanting to look at this subject from a biblical perspective would do well to start with this book. And in today’s #MeToo world, church leaders cannot afford to be ignorant of these issues.

Brian Davies, Aquinas: An Introduction (Continuum, 2002). With chapters on the existence of God, the simplicity of God, and the goodness of God (and 18 other chapters), this book will help dispel a number of misunderstandings about Aquinas. Although the writing is not spectacular, Davies is an expert in his subject and provides a solid introduction to one of the church’s most influential thinkers.

John Piper, Expository Exultation: Christian Preaching as Worship (Crossway, 2018). Those who follow Piper’s ministry carefully will recognize a number of common themes (eloquence, joy, affections) and some familiar strategies (APTAT) from earlier works and lectures. But this is not a recycled collection of essays. Rather, we have mature homiletical reflections from one of the most powerful preachers of the last generation. With careful exegesis, the skillful use of history, and an eye toward practical application, this book is pure Piper.

Spencer W. McBride, Pulpit & Nation: Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America (University of Virginia Press, 2016). An impressive collection of essays on the often overlooked role pastors played in the founding of America. The six chapters cover a ninteresting array of topics, from the role of chaplains to national days of fasting and prayer, even if the book’s overall narrative seems disjointed at times.

Warren Treadgold, The University We Need: Reforming American Higher Education (Encounter, 2018). With an impressive academic pedigree and the better part of his life in university life, Treadgold pulls no punches in criticizing American higher education as being obsessed with race, class, and gender instead of producing intellectually rigorous scholarship. Treadgold’s solution—a new university and two new federal boards—was not convincing, but his assessment of the problem deserves attention.

Jeffrey S. McDonald, John Gerstner and the Renewal of Presbyterian and Reformed Evangelicalism in Modern America (Pickwick, 2017). Gerstner’s role in the neo-evangelical project is easily overlooked. In fact, without his most famous student (R. C. Sproul), Professor Gerstner would be almost forgotten. This is a shame and not at all commensurate with the influence Gerstner exerted in the Reformed world and beyond. McDonald’s prose does not leap off the page, but he is surely to be commended for his careful historical work and for bringing to light the key role Gerstner played in evangelicalism in the second half of the last century.

Christopher Buckley, The Judge Hunter (Simon & Schuster, 2018). Set in the two worlds of England and New England/New Amsterdam, Buckley tells the fictional story of Balthasar St. Michel’s errand to hunt down regicide judges in America. With a keen sense of humor and careful attention to historical detail, Buckley’s novel is fun and entertaining. Buckley (William F. Buckley’s talented son) is an excellent writer. I only wish he would keep out the sexual innuendo humor that marks this book and the others I’ve read from him.

November 19, 2018

Are We Really in Danger of Making an Idol of the Family?

“One of the acceptable idolatries among evangelical Christians is the idolatry of the family.”

That’s what I tweeted last week. To be honest, I didn’t think much about it. I’ve said similar things in sermons for the past decade, and I’ve tweeted similar things before. But this time—I was later told by friends who track with Twitter more closely than I do—the statement took on a life of its own as this one sentence was liked 1,600 times and bandied about on social media for the next few days. Unknown to me, I was (depending on who you ask) suddenly saying something wonderfully courageous or terribly misguided.

So let me clarify.

As far as I can tell, I first uttered this statement (or something close to it) in a 2010 sermon on Mark 3:31-35 entitled Jesus’s Real Family. The tweet itself comes from a more recent sermon on the miracle at Cana in Galilee. My point in both cases was that a commitment to family must not come before a commitment to God.

I began the Mark 3 sermon by noting two competing notions of the family in our culture: family as straight jacket (as in the 1998 film Pleasantville) or family as center (as in the 2000 film The Family Man). In one view, the family keeps you from everything you really want. In the other view, the family promises to give you everything you really want. Jesus promoted neither of these views. There’s no doubt the second view is much more common among Christians, and it does overlap with some Christian virtues. But it too gets some crucial things wrong when it comes to the family. I argued back in 2010 (and would argue the same today) that, according to the Bible, the family is good, necessary, and foundational, but not ultimate.

The Mark 3 sermon focused on those two words—“not ultimate”—because that was Jesus’s emphasis in verses 31-35. In Jesus’s view of the family: family ties don’t get you in, family doesn’t come first, and God’s family is open to all (that is, open to everyone who does the will of God and takes Jesus on his own terms).

There are certainly ways in which speaking of “the idolatry of the family” would be a step in the wrong direction. I’m happily married with (soon) eight children. I am most definitely a family man (and have a 15-passenger van to prove it). I would never suggest that the real problem in the world today is that parents love their kids too much or that churches are doing too much to support the family or that what really ails our culture are too many high-functioning families. In a world hellbent on redefining marriage and undermining the fundamental importance of the family, Christians would do well to honor and support all those trying to nurture healthy families.

And yet, virtually every pastor in American can tell you stories of churchgoers who have functionally displaced God in favor of the family.

Parents who go missing from church for entire seasons because of Billy’s youth soccer league or Sally’s burgeoning volleyball career.

Committed Christians who would never dare invite a college student or international over for Thanksgiving or Christmas because “the holidays are for family.”

Longtime members who can’t be bothered to serve on Sundays or reach out to visitors because the whole family always gathers at grandma’s for lunch.

Kids and grandkids who think they should be accepted into membership or be in line for baptism because their parents and grandparents have been pillars of the church.

Churches that implicitly (or explicitly) communicate that marriage is a necessary step of spiritual maturity.

Christians of all kinds who will jettison their theology of marriage or their convictions about church discipline once their children come out of the closet or embrace other kinds of (unrepentant) sin.

The idolatry of the family can be a real problem, either from the church that ignores singles and gears everything toward married couples with children, or from the individual whose practical commitments underscore the unfortunate reality that blood is usually thicker than theology.

God has given us many gifts in this life. Money is a gift. Sex is a gift. Work is a gift. Athletic ability and musical skill are gifts; so are intelligence and beauty. No one doubts that all of these good things can be idols. Just like the family. The conjugal family—one man and one woman whose covenant union produces offspring—is profoundly good, a necessary and foundational element of God’s creational design. But it is not ultimate. At least not if we are defining family as the natural relationships we have by marriage and blood, rather than the supernatural relationships we have by the blood of Christ.

November 12, 2018

Eleven Ways Christians Can Love One Another

I lead our new member’s class at church. It’s a 12-week class, with about half the class spent on the Westminster Confession of Faith, while the other half deals with the ins and outs of Christ Covenant and the basics of Christian discipleship. I always take one week to talk about loving one another as the body of Christ.

My aid for this lesson is Ed Welch’s terrifically practical book Side by Side. I love the book’s two big ideas: We are all needy, and we are all needed. Under that second theme are eleven short chapters (Remember: We Have the Spirit; Move toward and Greet One Another; Have Thoughtful Conversations; See the Good, Enjoy One Another; Walk Together, Tell Stories; Have Compassion during Trouble; Pray During Trouble; Be Alert to Satan’s Devices; Prepare to Talk about Sin; Help Fellow Sinners; Keep the Story in View).

These are great titles by themselves, but in the class I try to summarize each chapter with a short phrase. In turn, these become eleven pithy suggestions for loving one another in the church. I find them helpful. Maybe you will too.

1. Ordinary people, ordinary ways. Loving people can require extraordinary effort, but it doesn’t require extraordinary gifting. Talk to people. Get to know them. Be a good listener. God has given you wisdom. He’s given you his Spirit. Don’t be afraid.

2. Start small and push through the awkwardness. I used to disdain so much small talk in the church, until a seasoned pastor reminded me that most people have to wade in the shallow end before they’ll try swimming in the deep. Except for the most extroverted among us, getting to know people is challenging. But Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither are friendships. Keep your hand to the relational plow.

3. Follow the affections. Facts are important too. But don’t just ask about the test results and the medication and the next doctor’s visit. We must be willing to talk about fears and worries and doubts and joys and hopes and disappointments.

4. See, and let them know you see. “See something, say something” is not just good advice for stopping the bad guys. It’s good advice for pointing out the good in other people. Have you noticed the Spirit’s gifts, or better yet the Spirit’s fruit, in someone else? Write him a note. Tell her what you’re thankful for.

5. Draw out and ask for stories. How did you become a Christian? What drew you to your line of work? Tell me about your kids. How did you two meet? What were your traditions around the holidays? One of the greatest gifts you can give to others is the gift of your curiosity.

6. Speak from the heart and remember. Don’t let suffering scare you away. That’s when others need you the most. Don’t lecture. Don’t push them away with pious platitudes. Tell them you’re sorry. Take the initiative to help. Don’t forget.

7. Pray and follow up. I always find it amazing (and encouraging) that so many people will pray for me in a time of crisis or pain. I find it doubly amazing when those people circle back a week later, or a month later, or a year later, and tell me they are still praying and ask how I am doing.

8. Keep in mind, suffering is a battle ground. We don’t just experience life. We all interpret what we experience. When suffering comes–and it comes to all of us–we will be tempted to interpret our pain incorrectly (e.g., God is out to get me, I’m unlucky, nothing really matters). We need each other to suffer well.

9. Exercise patience and humility. Real love means getting into real problems. Most people, however, prefer to talk about their circumstantial problems, not their real problems. So if we are going to love one another, we must deal humbly with other people’s anger and other people’s failures.

10. Have the courage to confront. Love may cover a multitude of sins, but it does not overlook every sin for all time. Sin is one of the main things we all have in common. Let’s not be afraid to talk about it.

11. Deal with past, present, and future. It’s easy for us to relate to people only in the present. What’s going on today? How are you feeling right now? But wise counselors will also look into the past (to see how history has affected our interpretation of reality) and bring the future to bear on the present. Christians of all people must live in light of the end of the story.