Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 9

February 25, 2020

Seven Questions to Ask in Evaluating Online Pundits

One of the best things about the internet is that anyone can state his opinion about anything.

And one of the worst things about the internet is that anyone can state his opinion about anything.

The digital revolution has made knowledge more accessible, the flow of information more diverse, and the ability to make your voice heard easier than ever.

The same revolution has also made invincible ignorance more sustainable, pervasive crankery more common, and the ability to discern what voices are worth listening to harder than ever.

There’s no putting the genie back the bottle. Even if more news and punditry is being “curated” these days, it’s still the case than anyone with a strong opinion and the self-discipline (or blinding rage, the case may be) to blog and tweet and post consistently can command a following and wield a level of influence that would have been unthinkable twenty years ago. If we are to be wise, then, in both what we read online and how we read it, we need to stand by the unpopular conclusion that not all opinions are created equal.

In his book The Death of Expertise, Tom Nichols tells the story of an undergraduate student arguing with a renowned astrophysicist who was on campus to give a lecture about missile defense. After seeing that the famous scientist was not going to change his mind after hearing the arguments from a college sophomore, the student finished in a harrumph, “Well, your guess is as good as mine.” At which point the astrophysicist quickly interjected, “No, no, no. My guesses are much, much better than yours” (82-83). Just because someone is confident, doesn’t mean he is anywhere close to correct.

So how do we evaluate the cacophony of punditry around us, especially the online variety? Few of us have time to research every author we read, let alone the subject matter on which they are pontificating. But there are several common sense questions we can run through our brains before giving undue credence to the latest and loudest opinions.

1. Does this person inhabit a healthy web of family and friends? Of the questions listed here, this is the hardest to answer. Often, we won’t know anything about the person we are reading online. But at times, we may be able to discern something of a relational pattern, for good or ill. To be sure, even nasty folks can find a friend or two, and sometimes the best people suffer through family drama not of their own making. And yet, as a general rule, if I know someone has a good marriage, a happy home life, a lot of supportive friends at church and at work, and a long track record of strong relationships, I’m more inclined to hear what he has to say, especially on spiritual matters. Conversely, I’m less likely to consider someone an expert on spiritual matters who is surrounded by a train of relational wreckage with himself at the center. We are whole people, and those who are emotionally unhealthy and unstable are not usually the best go-to guides for fair analysis and discernment.

2. Does this person have full-time responsibilities beyond independent punditry? Again, there are exceptions. Tim Challies, for example, has proven to be one the most trustworthy and reliable voices on the internet. He made his name as an independent blogger and has kept up the good work for years. But he’s the exception that proves the rule. When I read some people online I can’t help but think, “What do you actually do for a living?” I’m not talking about full-time moms either. I’m talking about people who don’t seem to be running a church, running a business, running a family, or punching in regular hours to pay the bills. If you mainly hang-out online responding to every mention on Twitter, provoking your opponents, fishing for compliments, and getting into digital fights every few days, I wonder if you have the real-world maturity and perspective to be helpful. I take inveterate pugilists and narcissists with a massive grain of salt.

3. Does this person have the commensurate education or experience that makes them worth listening to? Yes, I know the talk of academic degrees can sound hopelessly elitist. There are plenty of dumb smart people in the world. But when it comes to real expertise, there is a big difference between someone who has taken years or decades to become acquainted with a subject and someone who has been looking into a given person, place, or thing for a few weeks (or minutes!). I prefer to listen to people who know more than I do, not simply emote their convictions more strongly.

4. Is this person held accountable by any meaningful institutions? When it comes to public controversy, institutions are always at a disadvantage. A lone blogger or tweeter can make allegations, respond to comments, and be single-minded in his effort to expose what he sees as corruption or error in a church, school, organization, or business. And sometimes, we need these whistle blowers to see what everyone refuses to see. Institutions do make mistakes; they can become corrupt. But lone wolves can make mistakes and be corrupt too. And when they are, the institutions they oppose are at a profound disadvantage. An individual can post and respond with relative impunity. Institutions have to move slowly and cautiously. They have boards and employees and constituencies to think about, not to mention financial and legal ramifications. This doesn’t mean that belonging to an institution makes one right, but I generally feel more confident about someone who is actively involved in and accountable to a church, a session, an employer, a school, a board, a presbytery, or some combination thereof, than I do about someone whose performance, ideas, and behavior reflect on no one but himself.

5. Does this person provide the necessary links and citations to bolster his assertions? Fairly often, I will have people in my church ask about articles and allegations they read online. Usually, the accusations involve people they thought they could trust, but now appear to be mixed up in some nefarious underworld. Almost always, the accusations brought to my attention come from those (the online source, not the people in my church) who provide no hard facts to substantiate their slanderous claims. When links are provided, they are often nothing more than elaborate attempts at guilt by association. The click bait is usually the product of hearsay, half truths, and an eagerness to believe the worst about people. Or else the most serious charges are based upon unproveable and ambiguous accusations about Illuminati-like conspiracy theories. Likewise, just the mere recitation of a claim does not make it true. If I assert that Organization X is funded by blood money, and Leader Y is a closet Zoroastrian, and Institution Z drowns puppies behind closed doors, those claims are no more true because I repeat them and no more tied to facts because other people start to assume them to be true.

6. Does this person express his opinions and state his case with a due sense of proportion? This rule of thumb will serve you well: don’t believe hysterics. If the matter at hand is truly grave, the facts should speak for themselves. Or if we must use hard words, make sure they are in conjunction with even firmer arguments. When everything in one’s public profile is a five alarm fire, I tend to think the pundit is interested in starting fires more than in putting them out.

7. Does this person exhibit any interest in trying to understand the arguments of others or speak carefully about those he means to criticize? I can learn a lot from people who try to persuade. I learn little from people who do nothing but berate. When a writer, thinker, or critic never sees any good points on the other side, or never sees any trade-offs in his own position, I question his commitment to intellectual rigor. Likewise, when a pundit always–forever and ever, amen–finds fault in people to the left of him or only in people to the right of him, it makes me think the punditry is about party loyalty more than a honest search for truth.

Granted, these tests aren’t foolproof. There are exceptions to all these “rules.” But rarely does someone break all (or most) of these “rules” and prove to be a trustworthy voice. We owe it to our families, our friends, our churches, and to ourselves to think critically before we take in gossip, pass along slander, or simply succumb to logical nincompoopery and ill-founded bloviating passed off as courage.

February 17, 2020

How to Improve Your Preaching

For the past few years I’ve been thinking often about how I can improve as a preacher. I’m 42 years old, and I’ve been preaching pretty much every week since I was 25. In that time I’ve preached around 75 different messages every year. You can do the math; that’s a lot of sermons. I hope my sermons are better than they used to be.

And I hope I am still improving. Preaching is a funny thing. It’s part science and part art. It takes a lot of hard work and discipline, but also a tremendous amount of creativity. As a pastor, nothing feels as satisfying as a good sermon, and almost everything feels easier to do.

Evaluating preaching is extremely difficult. I’ve heard sermons that are models of the craft, but lack all unction and power. I’ve also heard disastrous sermons, from a technical standpoint, that nevertheless communicate the biblical text in an effective way and connect with the heart on a deep level. I bet I’ve preached both kinds of sermons.

If homiletical evaluation is tricky, it’s also terribly subjective. I know some people think my preaching is too meaty. Other people have said I have too much humor. They may both be right, or both wrong. It’s hard to say. Even our preaching heroes elicit varying responses. Spurgeon was undoubtedly brilliant, but was he a model expositor? Lloyd-Jones is one of my favorites, but he had all sorts of habits that should not be imitated. There is no one way to preach a faithful, effective sermon, and no one way to evaluate sermons. Even if I could get the godliest members in my congregation to give me the most candid feedback about my preaching, I imagine I would hear—along with many common themes—a wide variety of strengths and weaknesses.

But back to my main point: I want to get better. I may be a leader, counselor, manager, team builder, writer, teacher, mentor, discipler, editor, fundraiser, and a dozen others things as a pastor. But as the senior pastor the main thing I do is preach. I’d like to be as good at this one thing as possible. If others are supposed to see my progress (1 Tim. 4:15), I hope one area in which they see progress is my preaching.

So I keep listening to other preaching (although less than when I was a younger preacher), and I keep on reading (and re-reading) books on preaching. I don’t hold myself up as a homiletical model. I resonate with Lloyd-Jones’s comment that he wouldn’t walk across the street to hear himself preach. But since the dear saints at Christ Covenant do walk across the street to hear me preach, I want to preach as winsomely and faithfully as I can.

Questions to Ask

Here, then, are 11 questions I’ve been asking myself as I think about improving as a preacher. I don’t use these as any kind of weekly checklist, but these are the sorts of things rattling through my head and heart.

Am I cutting corners in my preparation? I’m not a slave to any particular rule about time spent in study. The whole “one hour in study for every minute in the pulpit” has always seemed ridiculously unattainable, and usually makes for overly stuffed sermons. The longer I’m a preacher, the less time it takes to produce a good sermon. That’s the way it should be with anyone in any craft. I’m also sympathetic to the pastor who has Sunday morning, Sunday evening, Sunday school, and Wednesday evening prep to do. There simply aren’t enough hours in the week to produce four (or three? or sometimes two?) quality messages. You have to borrow old material. You have to give one of those settings less than your best. But all those caveats aside, I want to make sure I’m not in the habit of recycling old material for the main teaching time, or leaning on the digested work of others, or letting all the demands of ministry crowd out my preparation week after week. Good sermons take time.

Did I learn anything new in my preparation? I love teaching and preaching because I love learning. I have to use old material at times (especially when speaking outside my church), but the thrill of preaching is much less that way. Half the excitement is having learned something new during the week that I get to share with others. Basically, preachers can hold the congregation’s attention in three ways: with the force of their personality, with the genius of their stories, or with the intellectual stimulation of their content. Of course, the Spirit is at work too and can work through all of these. But I think too many preachers run out of interesting things to say so they fall back on their own pathos (sometimes manufactured) to keep people engaged each week.

Was I personally moved by anything in my preparation? I don’t just want to learn new things in my study. I want to feel new things, or have old affections rekindled. It is hard for a sermon to move others that hasn’t first moved us.

Did the best parts of the sermon come from my closest attention to the text? Too often, the real payoff in the sermon has little to do with exegetical insight from the passage. The power (or so it seems) comes from an illustration, a rant, or a well-placed aside instead of from the treasures we’ve unearthed from the Bible in the past week.

Did the mood of the sermon match the mood of the text? Sermons sound the same when the text always takes on the personality of the preacher. So, if you are a caring, tender shepherd, every sermon sounds like a soothing balm of Gilead. If you are a rebuker and exhorter, every sermon feels like a finger in your chest. It’s impossible to completely divorce the preacher’s personality from the sermon, but every preacher must be careful that he lets the text set the mood not his personality. Gospel-centered preaching doesn’t mean every sermon feels like the same message about acceptance in Christ. Sermons should be comforting, threatening, indicative-based, imperative-heavy, transcendent, or immanent depending on the mood of the text.

Am I getting enough sleep? It’s hard to be emotionally healthy, intellectually rigorous, and rhetorically creative when you are exhausted.

Am I getting consistent exercise? You’ve read all the studies: our brains work better when are bodies are engaged in regular movement and activity. The best sermon prep is often a long walk.

Am I reading well and reading widely? To be sure, you can be a good preacher without being an avid reader. Not all preachers in all places at all times have had the access to good books that we have. But most people reading this blog have access to an embarrassment of theological, educational, and literary resources. I know I am much better equipped for the intense outflow that is congregational preaching, when I have a strong inflow of ideas from other sources. That means I need books, articles, stories, lectures, or almost anything that keeps my mind fresh, stretched, and engaged.

Am I thinking through the pacing and dynamics of my preaching style? We all have different personalities that will shape our sense of fast and slow, of loud and quiet. The key is not some rigid standard of uniformity, but the thoughtful variation of speed and sound. When I suggested on another occasion that we might want to shorten our sermons, the advice wasn’t meant to eliminate important content. Rather, the comment was borne out of the conviction that many of us can eliminate unimportant content. We spin our wheels in preaching instead of moving on to the next point. We stay at one emotional pitch during the entire sermon. We are tour guides who only know one way of showing people around the gallery.

Have I considered experimenting with what I bring into the pulpit? I was taught in seminary to preach without notes. I did that for several years until I felt like I was wasting hours memorizing each week. I’ve tried using manuscripts too. That’s what most of my friends seem to do. The discipline is good for me, and it makes the sermons much more useful in the rear-view mirror. For most of my ministry, however, I’ve used full-ish notes. I used to bring 6-7 pages of notes, then 5-6, now it’s usually 4 pages. Each method—notes, no notes, manuscript—have their pros and cons. Why not try out one of the other approaches from time to time to see what you might like or learn?

Did I pray?

I still have lots to learn, but I am hoping to get better. Preachers, let’s give ourselves to this task with renewed zeal and discipline. Congregants, please pray for your pastor when he stumbles and encourage him when he hits the mark. And if you think we need help, keep in mind most pastors are more sensitive than they let on.

February 4, 2020

Book Briefs: February 2020

Here is a selection of what I’ve been reading since the beginning of the new year.

Malcom Gladwell, Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know about the People We Don’t Know (Little, Brown, 2019). I know Gladwell is a simplifier. He takes complex subjects and writes about them in ways that scholars probably find frustrating. But no one can tell a better (non-fiction) story than Gladwell. From spies in Cuba to terrorists in the Middle East, this book was fascinating from start to finish, and in the process Gladwell comes to a number of surprising conclusions. Note: I listened to the book on Audible, and it was masterfully done, more like a podcast than an audiobook.

James Clear, Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones (Avery, 2018). I’m a sucker for books on habits and productivity. If you keep in mind the genre—not a Christian book, so no understanding of the gospel or the Holy Spirit or heart change—this is an excellent book. Don’t let the title throw you off. Clear does not oversell his method, nor does he promise drastic life change in two weeks. But the book is a quick read (or listen) and will give you several good strategies for making small improvements right away.

Thomas R. Schreiner, Spiritual Gifts: What They Are and Why They Matter (B&H, 2018). This is an excellent primer on spiritual gifts from a cessastionist perspective. Shreiner is unrelentingly kind and fair in his analysis, especially when he disagrees with continuationists. There are more comprehensive books on the subject, but for an introductory volume this one is hard to beat.

Jonathan I. Griffiths, Preaching in the New Testament: An Exegetical and Biblical-Theological Study (Apollos, 2017). I’ve yet to be disappointed with Carson’s New Studies in Biblical Theology. This is one of the shorter ones in the series and one of the best ones too. The gist: “Preaching in the New Testament is a public declaration of God’s word by a commissioned agent that stands in a line of continuity with Old Testament prophetic ministry” (128-129). Griffiths argues, as I noted elsewhere, that there is such a thing as preaching, and not everyone does it.

Barry Hankins, Uneasy in Babylon: Southern Baptist Conservatives and American Culture (University of Alabama Press, 2002). Almost two decades old, Hankins readable analysis is still a helpful reflection on the conservative resurgence in the SBC in the last part of the 20h century. As the title suggests, central to Hankins’s thesis is the idea that SBC conservatives reasserted themselves due to a growing sense that they needed to be less parochial and more counter-cultural at the same time.

Stephen F. Knott, The Lost Soul of the American Presidency: The Decline into Demagoguery and the Prospects for Renewal (University Press of Kansas, 2019). Knott argues that James Madison and Alexander Hamilton envisioned a presidency—which George Washington fulfilled—that would be removed from the “passions” of the people and show little concerns for “the little arts of popularity.” Unfortunately, this vision of the American presidency began to lose its soul under Thomas Jefferson and unraveled under Andrew Jackson. Abraham Lincoln was (mostly) a return to the Hamiltonian vision, but the decline into demagoguery accelerated once again with Woodrow Wilson and has reached its apotheosis with Donald Trump. While Knott’s thesis is plausible, the second half of the book was not as strong as the first half. After dealing carefully with Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, and Jackson, more recent presidents are covered so quickly and lightly that it feels like almost any thesis could stick.

Gregg Hurwitz, Orphan X (Minotaur Books, 2016). And now for something completely different—a high-tech thriller where the good guy tries to help people in need. Evan Smoak is the Nowhere Man, taken as a boy and trained to be a secret agent with incomprehensible skills and abilities. You’ll need to skip a few sections (like I did) that get unnecessarily racy. But if you don’t mind rooting for an assassin (with a moral compass) you will enjoy Orphan X. A page-turner filled with surprises.

January 30, 2020

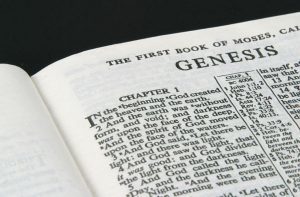

What Can We Learn from the #MeToo Moments in Genesis?

The first book of the Bible is a picture of sin run amuck. Of course, we also find in Genesis a display of God’s creative power, his plan of redemption, and his sovereign mercy in blessing his undeserving people. But even amid this wonderful good news, we see plenty of examples of the corrupting effects of sin from Genesis 3 through the end of the book.

In particular, Genesis is replete with examples of sexual sin. From Sodom and Gomorrah to Dinah and the Shechemites, some of the most horrific examples of sexual sin are found in Genesis. Most students of the Bible know those (in)famous stories of male sexual violence and assault. What we may have missed, however, is how diverse the other stories of sexual sin are in Genesis.

This point about the diversity of sins is convincingly demonstrated by Brian Neil Peterson in his article “Male and Female Sexual Exploitation in Light of the Book of Genesis” in the latest issue of the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (62.4 [2019]: 693-703).

Peterson, associate professor of OT at Lee University, makes the case that sexual abuse and abuse of power in Genesis cannot be confined to one pattern. While there are several examples of men sexually exploiting women, there are also examples of sexual sin and abuses of power involving men and men, women and women, and even cases of women sexually exploiting men. Peterson repeats several times that he does not want to minimize any of the sexual sins of guilty men—past, present, or future. At the same, if we are to do justice to the record of sin in Genesis, we must acknowledge that sexual exploitation has been part of the human condition, irrespective of gender, from the beginning of recorded history (694). With Genesis as an inspired and trustworthy account of sin’s work in the world, we should expect sexual sin and abuses of power to characterize both men and women, even if more prevalent by men.

Sexual Exploitation in Genesis

The brilliance of Peterson’s article is its simplicity. Once he lays out the examples in Genesis, the data looks exceptionally clear and compelling (701-702). Peterson points to more than a dozen examples of sexual exploitation in Genesis.

Many of the most (in)famous examples are of men sinning against women:

Abraham leverages Sarah’s sexuality, putting his wife at risk in order to save himself (Gen. 12, 20).

Lot offers his daughters for the sexual pleasure (essentially rape) of the clamoring men at his door (Gen. 19).

Isaac leverages Rebekah’s sexuality, putting his wife at risk in order to save himself (Gen. 26).

Laban uses Leah’s sexuality for financial gain (Gen. 29).

Shechem rapes Dinah (Gen. 34).

Reuben takes advantage of Bilhah, his father’s concubine, and has sex with her (Gen. 35).

Clearly, these are heinous examples of men—for their own protection or pleasure—sacrificing, seducing, or raping women. We cannot denounce these sins too strongly. And note, the examples above do not include the sin of polygamy—which was not part of God’s original good design and which almost always carries negative results in the biblical narrative. Polygamy can be seen as further exploitation of men against women.

There are also examples of men sinning against men:

Ham takes advantage of Noah and engages in some form of inappropriate and shameful sexual behavior regarding his father (Gen. 9).

The men of Sodom clamor for sex with Lot’s male visitors, who are really angels (Gen. 19).

Peterson also mentions that Ishmael may have sexually abused his younger brother, Isaac, taking the language of “mocked” or “laughing” to be fondling or caressing (Gen. 21).

The sin of sexual exploitation, however, is not only a male problem. We also see examples of women sinning against women.

Sarah forces her servant, Hagar, to sleep with Abraham and be a surrogate womb for her (Gen. 16).

Leah does the same thing with her servant, Zilpah (Gen. 30).

Rachel, in turn, uses her servant, Bilhah, in the same way (Gen. 30).

Finally, there are also several examples of women sinning sexually against men:

Lot’s daughters conspire to get their father drunk and then both have sex with him so they can get pregnant (Gen. 19).

Leah and Rachel bargain for Jacob’s sexual service in hopes of getting pregnant (Gen. 30).

Tamar—who was previously sinned against—tricks and seduces Judah, her father-in-law, into having sex with her and getting her pregnant (Gen. 38).

Potiphar’s wife tries to seduce Joseph and then lies about him when he refuses her advances (Gen. 39).

Clearly, sexual exploitation is not a one-way street in Genesis. This is not to suggest that the severity of each sin is the same, nor that the experience of being sinned against is the same in each instance. The point of comparison is not to foster a false moral equivalency, but to make the necessary point that sexual sins can be committed by men and committed by women, against men and against women.

Three Points

So what does this mean for our current cultural context? Three brief points.

One, we certainly don’t want to use Genesis to minimize the sin of men against women (or the sin of anyone against anyone!). The point of Peterson’s article—and the point of this post—is not to say, “Sexual sin and the abuse of power is no big deal,” or even to suggest that men and women commit this type of sin in equal numbers. Sexual exploitation is always a grievous sin.

Two, I can’t help but notice how men and women in Genesis sin in ways we might expect from men and women. The examples of sexual exploitation at the hands of men involve violence, physical abuse, and using female sexuality for personal gain. Women can sin in these ways too, of course, but it’s striking that the examples of sexual exploitation at the hands of women involve seduction, deceit, and the desire for motherhood at all costs. Surely, there is a lesson to be learned in the particular ways that men and women can be tempted to sexual sin and the abuse of power. The almost universal facts of nature are that men are physically stronger than women and more easily aroused than women. This means that sex is too often something men forcibly try to take from women, while sexuality is something women too often wield as a great power in relationships with men. Genesis shows that both happen in a fallen world and that both are wrong.

Three, while there is much good that can and has come from our cultural #MeToo moment, it would be a betrayal of biblical anthropology in general, and the testimony of Genesis in particular, to think that sexual sin and exploitation only occur at the hands of men against women. It’s simply not biblical to posit a matrix of oppression confined to tidy categories that only move in one direction. While certain ways of sinning may be more common to one gender, we should not think that either men or women are free from the sins of the flesh depicted so vividly in the first book of the Bible.

January 21, 2020

A Prayer on Race and Roe

The following is an edited version of my pastoral prayer from this past Sunday at Christ Covenant.

O loving and sovereign God, our heavenly Father, we come to you in the name of Jesus, your Son, our Lord, asking that you would hear our prayers for his sake.

In your providence, you have arranged for this week in January that we in America would be reminded of two of our most heinous national sins.

We celebrate this week Martin Luther King Jr., a man who not only exposed racism in this country but also called us to dream of a day when we would not be judged by the color of our skin, but by the content of our character. We give thanks for all the ways racism is less evident, less prevalent, and much less accepted today than it was 50 years ago.

We thank you for the different nationalities and ethnicities present in our church. We rejoice to know that there will people around your throne from every tribe, every tongue, and every language. In so far as we are able—given our time and place as a congregation—help us to reflect this reality. Show us our abiding sins and shortcomings. Give us grace, insight, and self-awareness that we might remove barriers to the faith and barriers to the church, save for offense of your truth and the enduring scandal of the cross.

While there is much to celebrate regarding racial harmony in this country, compared to where we have been, there is also much to pray for.

Wherever there are suspicions based on stereotypes and bigotry, forgive us. Wherever there is animus or prejudice based on differences in history, race, or economics, convict us. Wherever we are in bondage to self-pity or self-protection, redeem us. Wherever we are crass, insensitive, unthinking, or unfeeling toward the hurts and injustices others have experienced, deliver us.

May those who belong to groups that have historically been shown prejudice in this country be free from bitterness, anger, and thoughts of recrimination. May those who belong to groups that have historically been privileged in this country be free from ignorance, pride, and thoughts of superiority.

Keep us fixed on Christ, the author and perfecter of our faith. Change structures and systems where they are unjust. Change politicians and policies where they stir up division or seek out votes based on racial disunity.

Most of all, change the hearts of all those who are far from Christ and far from each other. May we all see the image of God in one another. And may we who call upon the name of Christ see in one another a brother, a sister, a certain heavenly companion, and the makings of an earthly friend.

We will also remember this week the anniversary of the legalization of abortion in Roe v. Wade. Just as the thought of slavery and lynchings is a tragic stain on our country, so is the scourge of abortion on demand. We could add together all the people living in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and Tennessee, and still it would be fewer than the number of children killed by abortion since 1973. We pray that you would stay your hand of judgment—a judgment our nation richly deserves.

Have mercy upon us, O Lord. Forgive our apathy and indifference. Bring healing to those who have performed abortions, had an abortion, or pressured others to get an abortion. Lead us to the cross of Christ where no sin is so big that your grace isn’t bigger still.

Give wisdom and courage to pro-life legislators and executives that they might protect the innocent and the vulnerable. May they work to ensure life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all Americans—in the womb and outside the womb, no matter how small, no matter their cognitive ability, no matter their dependence or independence. Give compassion and resolve to all those working with at-risk women. Give Christian doctors the knowledge to know what procedures and prescriptions are right and the conviction to never encourage a patient in a direction that is wrong.

Give to each of us a spirit of generosity that is supportive of birth, supportive of adoption, and supportive of foster care—in whatever ways we are able to be supportive given our season and station in life. Give to your people the spirit of Christ, who never pushed away children, but welcomed them into his arms, saying “for to such belong the kingdom of heaven.” May we live to see the day when not only legislation and judicial precedents are changed, but also minds and hearts and wills.

We confess that both of these matters, race and abortion, can seem like intractable problems—too complicated, too controversial, too entrenched. But your arm is not too short. No one is beyond your reach, and nothing is beyond your grasp. And so we pray that you would do more than all we could ask or imagine—for the common good, for the good of the gospel, and for the glory of your name. In Jesus we hope and in him we pray, Amen.

January 14, 2020

Theological Primer: The Existence of God

From time to time I make new entries in this continuing series called “Theological Primer.” The idea is to present big theological concepts in around 500 words. Today we will look at the existence of God.

The existence of God is not a conclusion to be reached so much as a given to be assumed. “In the beginning God” is, after all, how the Bible begins (Gen. 1:1). We all have an innate idea of God, a sense of the divine that leaves us without excuse (Rom. 1:19-20; Acts 17:24-28; Eccl. 3:11). Only the fool says in his heart there is no God (Ps. 14:1). God’s existence is the starting place for human knowledge, not the end point of human deduction.

This does not mean, however, that arguments for the existence of God are necessarily misguided. One can argue for the existence of God in a way that is subservient to human reason or in a way that supports divine revelation. Aquinas, for example, begins his discussion with Scripture, establishing God’s existence from Exodus 3:14 (“I am who I am”). Only after this does he argue that the existence of God can be proven “in five ways” (Summa Theologica, I. Q.2. Art.3):

Argument from motion: There cannot be an infinite regression of motion. Someone or something must have absolute actuality, an unmoved mover.

Argument from the nature of efficient causation: Cause and effect must have begun with some first cause.

Argument from possibility and necessity: Existence cannot come from non-existence. Something must exist of its own necessity, not as a mere possibility.

Argument from gradation: Something must be most good, most perfect, and most true—a supreme being from which all degrees of lesser perfection are determined.

Argument from the governance of the world: Some intelligent being must exist by whom all natural things are directed to their appointed ends.

Protestant theologians often built upon Aquinas’s Five Ways. Turretin, for example, posits four proofs for the existence of God: the voice of universal nature (which encapsulated most of Aquinas’s arguments), the intricate design of human beings, the testimony of conscience, and the religious nature of all peoples throughout history (Elenctic Theology, III.i.i-xxvii).

Similarly, Shedd mentions five principal arguments (Dogmatic Theology, 201-216): ontological (a Perfect Being greater than which nothing can be conceived must by necessity possess existence), cosmological (motion implies a Prime Mover), teleological (the world is marked by design), moral (the testimony of conscience), and historical (all peoples believe in some kind of Supreme Being).

To be sure, we should not try to argue people into the kingdom of God, much less build a theological system on a rationalistic foundation. We know from the Bible that belief in the existence of God is ultimately an article of faith (Heb. 11:6). Nevertheless, there is a place for showing that the existence of God is rational and makes better sense of the world than does atheistic unbelief. Philosophy and human reason must not be the starting point for faith, but they can be used to defend, clarify, and confirm the faith.

January 8, 2020

What Is Preaching (And Who Does It)?

One of the best books I read last year was Preaching in the New Testament (IVP, 2017) by Jonathan Griffiths. As part of D. A. Carson’s series New Studies in Biblical Theology, I expected the book to be exegetically rich and the cover to be slate gray. I was not disappointed on either account. Griffiths, a pastor in Ottawa, Canada, makes a compelling case that there is such a thing as preaching and that not every Christian is called to do it.

At the heart of Griffiths’s examination is this well-defended conclusion:

Preaching in the New Testament is a public declaration of God’s word by a commissioned agent that stands in a line of continuity with Old Testament prophetic ministry. (128-129)

Building on the work of Claire Smith, Griffiths argues that in the New Testament euangelizomai, katangello, and kerysso are semi-technical terms referring to the proclamation of the gospel. Griffiths charts all 54 uses of euangelizomai (“announce good news”), all 18 uses of katangello (“proclaim” or “announce”), and all 59 uses of kerysso (“make proclamation as a herald”). While the three terms are not employed in a uniform sense, they are “semi-technical” in that they normally refer to preaching by some recognized authority. Of the three verbs, kerysso is the most specialized term with the narrowest range of meaning. But even with the other terms, Griffiths notes, there are no examples in the New Testament where believers in general are commissioned or commanded to “preach” (36).

Preaching is a certain kind of speech carried out by certain kinds of people. Of course, there are other kinds of word ministries given to all believers (Eph. 6:13-17; Col. 3:16; 1 Thess. 1:8; 1 Pet. 3:15) but preaching (especially the speech signified by kerysso) is a ministry set apart. Paul’s charge to Timothy (2 Tim. 4:1-2) indicates not only that preaching is a task for one with commissioned authority, but also that the preacher is a man of God (2 Tim. 3:17) like the prophets of old (61-66). Likewise, Romans 10 assumes that New Testament preaching stands in continuity with the Old Testament prophetic ministry of Isaiah. We also see that being commissioned (i.e., sent out) is an essential prerequisite for preaching ministry.

As Griffiths moves through 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians 2-6, 1 Thessalonians 1-2, and Hebrews, he reinforces the main themes of the book: that New Testament preaching is powerful, that God speaks through gospel preaching, that God expects people to respond to preaching with faith and obedience, that preaching requires a commissioned speaker, that preaching stands in continuity with Old Testament prophetic ministry, and that preaching is, therefore, a unique word ministry.

Concluding Thoughts

So what does this mean for the church today? Griffiths offers several points of application, let me mention three of my own (which overlap with some of his).

1. Preaching is not what every Christian does. The work of heralding is related to other word ministries but is not identical with them. There are no instructions for non-leaders to preach or proclaim the gospel. Obviously, the Bible was written in Greek not in English. The apostles never used the word “preach,” but the words they did use under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit mean something distinct from bearing witness, one-to-one discipleship, or leading an inductive Bible study. There is such a thing as preaching, and not every Christian is called to do it.

2. The act of preaching is inherently authoritative. For some reason, I had not seen before how clear this is in Romans 10. Preachers preach the gospel. Yes, that’s clear. But what is also clear is that preachers don’t just decide themselves that they want to preach. They must be sent. Preaching implies a commissioned agent authorized to preach. Rightly understood, there is no preaching that does not come from an authority in the church and no preaching that does not carry with it God’s own authority. A corollary to this point, then, is that complementarians should not speak of “women preachers,” nor should we describe the word ministry of women as “preaching.” The use of such terminology is unwise and unbiblical.

3. Preaching is meant to lead to an encounter with God. The word of Christ preached is not only a word about Christ; it is a word from Christ (Rom. 10:17). Though coming from human lips, the preached word is nothing less than the divine word of God (1 Thess. 2:13). Think of the book of Hebrews, a word of exhortation (13:22) that most scholars now think is the earliest extant full-length Christian sermon. We see that preaching comes from a congregational leader (13:7-24). We see that preaching is an exposition of Scripture. And we see that in preaching we come face-to-face (or ear-to-ear, we might say) with the living God (3:7, 15; 4:7). God’s voice is heard in the Sunday sermon, which is why we are right to give preaching the central place in our worship services and why we should pray regularly for the powerful preaching of God’s Word.

December 30, 2019

A New Year’s Resolution: Don’t Try to Be With It

The headline on my Twitter feed was from CNN and linked to an article entitled “The Cultural Moments that Defined 2019.” The tweet rang out with this incredible announcement:

From Jennifer Lopez storming Milan Fashion Week in an updated version of her iconic Versace dress to the sale of a $120,000 banana, the year was full of unforgettable moments.

Where to begin with such pablum? One could point to the verbal downgrade of the word “iconic”–now nothing more than a synonym for pop-culture famous. One could also mention the absurdity of modern art whereby a piece of ordinary fruit is sold for a handsome annual salary. But I’d like to focus on the last two words: unforgettable moments.

Please.

With the exception of the mention of the Notre Dame fire, everything in the article (warning: risque images) is utterly and entirely forgettable. Virtually no one will care about Jane Fonda’s red coat years from now or months from now (or seconds from now?). Just like the Instagram post from Phoebe Waller-Bridge will not be etched in our collective memory. In fact, when I first typed the last sentence, I wrote Bridget Walker-Phoebe, because I couldn’t recall the name I read two minutes ago.

The pop culture style moments detailed by CNN mattered almost nil to almost everyone, and their long-term cultural import will likely be less than that. What we have here is pretty much the textbook definition of what will not be remembered.

Trivialities and the Weight of Glory

I’m not a technophobe. I have a blog, a Facebook page, a Twitter account, and enough teenagers in the house to keep me conversant with my fair share of pop culture. I’m not quitting social media. Neither do I think it’s all a waste of time.

But honestly, most of it is.

Of course, there are common grace gifts to enjoy in the latest viral videos, memes, and GIFs. And yet, there are more gifts–of common grace and special grace–to be enjoyed in an excellent book, a thoughtful conversation, a long walk, time in silence, time in prayer, and time in the Word. If I’m going to suffer from FOMO, I want it to be the fear of missing out on all the things I could be learning, all the ways I could be growing, or all the ways I could be a bigger blessing to my family, my church, and my friends.

C. John Sommerville noted two decades ago that the news makes us dumb. He’s more right with every passing year. Here’s what I said several years ago:

Sommerville’s main point is not that the news is dumb, but that we are dumb for paying so much attention to it. We have become conditioned to think that the really important stuff of life comes to us in a neat 24-hour news cycle. Worse than that, in our mobile-digital age most of us assume that news is happening every second of every minute of every hour of every day, and if we tune out (or turn off our phones) for more than a few hours (minutes?) we will be rendered out of touch and uninformed. That’s dumb.

The solution is not better news, but less of it. The problem is with the nature of news itself. The news is all about information. It’s about what’s trending now. It rarely concerns itself with the big questions of life. It focuses relentlessly on change, which, as Sommerville points out, gives it an inherent bias against conservatism and religious tradition. Our soundbite/twitter/vine/ticker-at-the-bottom-of-the-screen/countdown-clock/special-report culture of news encourage us to miss the forest of wisdom for the triviality of so many trees. As Malcolm Muggeridge once observed: if he had been a journalist in the Holy Land during Jesus’ ministry he probably would have wasted his time digging through Salome’s memoirs.

In terms of pop culture consumption, I’m more attuned to some areas than others. I went to a movie theater exactly zero times in 2019, but I’m sure I pay too much attention to sports. I feel no temptation to binge watch anything, but I can mindlessly thumb through Twitter (is there any other way to look at Twitter?). And don’t ask about email; I stay connected to my inbox like it was kidney dialysis.

I need a digital detox just like most of you. If I’m to get more of the deep stuff, I need to be weaned from most of the trivial stuff.

A Timeless Resolution

If you are in the business of making New Year’s resolutions, why not attempt one that saves time instead of depletes it? Give up trying to keep up. Let the pop culture whirlwind pass you by. Be wonderfully ignorant of the world of what’s happening now. Don’t worry, the important news will still get to you. But hopefully most of the other “news” won’t.

It can be scary to detach, even a little bit, from the screams of social media, Netflix, and cable news. But let’s not mistake knowledge for wisdom, or a multi-media platform for kingdom usefulness. There is no way to possibly stay with it, so why bother? Look out the window. Put down the phone. Lose touch with pop culture and reconnect with God. If you get to the end of 2020 and can’t recall any of the big style stories from CNN, don’t fret: in a few minutes no one else with either.

December 23, 2019

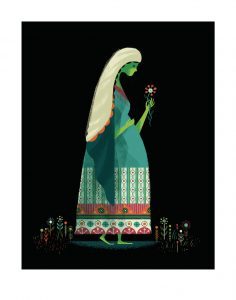

A New Baby and a New Beginning

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m working with Crossway on a children’s storybook Bible. The look and feel will be akin to The Biggest Story , but instead of covering the plot line of Scripture in one fell swoop, this will be a much bigger book with more than 100 Bible stories, like the one below. I’m thrilled to be working again with the extremely talented Don Clark, who will be providing the artwork to accompany my text. The book is scheduled to be released at the end of 2020 or beginning of 2021.

*******

The beginning of the Bible began with, well, a beginning. “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” That’s the first verse in Genesis, the first book of the Bible.

The New Testament begins with another beginning. “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ.” That’s the first verse in Matthew, the first book in the New Testament. “Genealogy” is a big word that has to do with tracing out your family tree. And that’s what we see at the start of the New Testament.

But here’s something special that your parents may not even know. The word that Matthew used when he wrote the verse is actually the word “genesis.” That’s right. Just like the first book of the Bible. The story Matthew wants to tell is about a new start, a new genesis, a new beginning.

Except this new beginning is definitely still connected to the old beginning. Jesus didn’t come out of nowhere, like a baby just fell from the sky (that would hurt). He wasn’t created with a magic wand or in a science lab. Jesus was a descendant of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He was from the tribe of Judah and the house of David. He had in his family tree mothers with strange stories like Tamar, amazing stories like Ruth, and sad stories like Bathsheba. Jesus was a real Jewish boy born into a real Jewish family with a real genealogy full of real promises and real people with real problems.

Jesus was just like us.

And he was unlike us. That’s how things work when you are God and man. Jesus was born like boys and girls are born, but his birth was unlike any before or since.

Mary and Joseph were engaged to be married. But before they even had a wedding, Mary was pregnant! This didn’t seem right, so Joseph had a plan to quietly breakup with Mary.

But before he could do that, an angel appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Don’t be afraid to take Mary as your wife. She’s not done anything wrong. The child in her belly is from the Holy Spirit.” If that wasn’t enough to make Joseph drop his hammer on his big toe, the angel had more to say. “Mary is going to have a son, and you should call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.”

Things were about to happen that people had hoped to see happen for a long time. Centuries earlier the prophet Isaiah predicted that a virgin would have a son and he would be called Immanuel, God with us. In other words, a young woman with no earthly way to be pregnant would give birth to a heavenly child.

Joseph woke up and did everything the angel told him to do. Mary had a son, and they named him Jesus, meaning “the Lord saves.” That was the perfect name for a perfect Savior—and a perfect new beginning to the story God had been writing even before the beginning of time.

December 10, 2019

Top 10 Books of 2019

First off, my usual disclaimer and explanation.

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of good books published in 2019. There are plenty of worthy titles that I am not able to read (and lots I never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year. “Best” doesn’t mean I agreed with everything in them; it means I found these books—all published in 2019—a strong combination of thoughtful, useful, interesting, helpful, insightful, and challenging.

10. Robert Louis Wilken. Liberty in the Things of God: The Christian Origins of Religious Freedom (Yale University Press). There have been plenty of books in recent years about current threats to religious freedom. This book is a look at the history of the idea. In particular, Wilken argues “religious freedom took form through the intellectual labors of men and women of faith who sought the liberty to love and serve God faithfully in the public square” (5-6). In other words, religious freedom was not a Christian capitulation to pluralism or Enlightenment philosophy, but a Christian idea in its own right.

10. Robert Louis Wilken. Liberty in the Things of God: The Christian Origins of Religious Freedom (Yale University Press). There have been plenty of books in recent years about current threats to religious freedom. This book is a look at the history of the idea. In particular, Wilken argues “religious freedom took form through the intellectual labors of men and women of faith who sought the liberty to love and serve God faithfully in the public square” (5-6). In other words, religious freedom was not a Christian capitulation to pluralism or Enlightenment philosophy, but a Christian idea in its own right.

9. Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones (eds). Making Evangelical History: Faith, Scholarship and the Evangelical Past (Routledge). If there is a theme that holds these chapters together it’s the tension between history that inspires the faithful and history that is faithful to the nuances, imperfections, and ambiguities of the past. I don’t believe the editors mean for Christians to choose between spiritual inspiration and intellectual rigor as mutually exclusive priorities, but they do mean to highlight how evangelical histories have typically aimed at the former more than the latter. For my part, I agree with Atherstone’s insistence that evangelicals ought to embrace both the “confessional” and also “professional” approaches to history (11).

9. Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones (eds). Making Evangelical History: Faith, Scholarship and the Evangelical Past (Routledge). If there is a theme that holds these chapters together it’s the tension between history that inspires the faithful and history that is faithful to the nuances, imperfections, and ambiguities of the past. I don’t believe the editors mean for Christians to choose between spiritual inspiration and intellectual rigor as mutually exclusive priorities, but they do mean to highlight how evangelical histories have typically aimed at the former more than the latter. For my part, I agree with Atherstone’s insistence that evangelicals ought to embrace both the “confessional” and also “professional” approaches to history (11).

8. Douglas Murray. The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race, and Identity (Bloomsbury). The fact that Murray is a gay atheist helps and hurts the book. On the one hand, it’s nice to see Murray sympathize with conservative Christianity and make the sorts of points many Christians would make. On the other hand, there is no doubt Murray is missing out on all sorts of resources and ideas for understanding human nature, sex, and forgiveness. Murray is at his best when he argues that our Western culture is asking for impossibilities. We must believe that women have a right to be sexy without being sexualized, that race doesn’t exist and that race defines everything, that Caitlyn Jenner is a woman but Rachel Dolezal is not black. His argument that people are much less oppressed than they think is bound to be controversial. But he makes a good point that the more comfortable most people are, the more suffering carries rhetorical (and real) power.

8. Douglas Murray. The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race, and Identity (Bloomsbury). The fact that Murray is a gay atheist helps and hurts the book. On the one hand, it’s nice to see Murray sympathize with conservative Christianity and make the sorts of points many Christians would make. On the other hand, there is no doubt Murray is missing out on all sorts of resources and ideas for understanding human nature, sex, and forgiveness. Murray is at his best when he argues that our Western culture is asking for impossibilities. We must believe that women have a right to be sexy without being sexualized, that race doesn’t exist and that race defines everything, that Caitlyn Jenner is a woman but Rachel Dolezal is not black. His argument that people are much less oppressed than they think is bound to be controversial. But he makes a good point that the more comfortable most people are, the more suffering carries rhetorical (and real) power.

7. Cal Newport. Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (Portfolio). After reading Newport’s earlier book on Deep Work, I was eager to get this follow-up volume on reducing digital distraction. Newport wisely observes that we are succumbing to screens not because we are lazy (though that may play a part), but because billions of dollars have been invested to push us into digital addiction. The call for digital minimalism, therefore, is not about efficiency or usefulness, but about autonomy. Like Newport’s book on work, I find this one easier to agree with than to put into practice.

7. Cal Newport. Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World (Portfolio). After reading Newport’s earlier book on Deep Work, I was eager to get this follow-up volume on reducing digital distraction. Newport wisely observes that we are succumbing to screens not because we are lazy (though that may play a part), but because billions of dollars have been invested to push us into digital addiction. The call for digital minimalism, therefore, is not about efficiency or usefulness, but about autonomy. Like Newport’s book on work, I find this one easier to agree with than to put into practice.

6. Robert Caro. Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Knopf). Fascinating from start to finish. I confess I have not read all of Caro’s famous work on LBJ, but I have read enough to know that as a researcher and political biographer, he has no equal. This little book is a snapshot into the subjects of his big biographies—Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson—as well as a glimpse into the method behind Caro’s own brilliant madness.

6. Robert Caro. Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Knopf). Fascinating from start to finish. I confess I have not read all of Caro’s famous work on LBJ, but I have read enough to know that as a researcher and political biographer, he has no equal. This little book is a snapshot into the subjects of his big biographies—Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson—as well as a glimpse into the method behind Caro’s own brilliant madness.

5. Stephen Witmer. A Big Gospel in Small Places: Why Ministry in Forgotten Communities Matter (IVP). A wonderful antidote to one of the last remaining prejudices: small towns are not strategic, and small-town folks are rednecks and rubes. With a good mix of theology, exegesis, cultural analysis, and personal reflections, Witmer manages to be warmly pro-small places without ever sounding anti-big cities. This book will encourage many and may be used by God to call good gospel ministers back into our forgotten communities.

5. Stephen Witmer. A Big Gospel in Small Places: Why Ministry in Forgotten Communities Matter (IVP). A wonderful antidote to one of the last remaining prejudices: small towns are not strategic, and small-town folks are rednecks and rubes. With a good mix of theology, exegesis, cultural analysis, and personal reflections, Witmer manages to be warmly pro-small places without ever sounding anti-big cities. This book will encourage many and may be used by God to call good gospel ministers back into our forgotten communities.

4. Kevin G. Harney. No Is a Beautiful Word: Hope and Help for the Overcommitted and (Occasionally) Exhausted (Zondervan). With 54 short chapters about saying “No,” you don’t have to wonder what the book’s big idea is all about. Nothing revolutionary, but lots of good illustrations, practical advice, and spine-stiffening courage for saying “No” to most things, so we can say “Yes” to the best things. A necessary book for anyone who feels margin-less, overstretched, and crazy busy.

4. Kevin G. Harney. No Is a Beautiful Word: Hope and Help for the Overcommitted and (Occasionally) Exhausted (Zondervan). With 54 short chapters about saying “No,” you don’t have to wonder what the book’s big idea is all about. Nothing revolutionary, but lots of good illustrations, practical advice, and spine-stiffening courage for saying “No” to most things, so we can say “Yes” to the best things. A necessary book for anyone who feels margin-less, overstretched, and crazy busy.

3. Carl H. Esbeck and Jonathan J. Den Hartog (eds). Disestablishment and Religious Dissent: Church-State Relations in the New American States 1776-1833 (University of Missouri Press). I know, the title screams “Take me to the beach!” But this really is a fascinating book. Each of the original 13 colonies, plus a few other early states, is given its own chapter. From New Jersey (the first and simplest case of disestablishment) to Massachusetts (the last and most complicated) a talented group of scholars detail the political, cultural, and legal process of disestablishment in early America.

3. Carl H. Esbeck and Jonathan J. Den Hartog (eds). Disestablishment and Religious Dissent: Church-State Relations in the New American States 1776-1833 (University of Missouri Press). I know, the title screams “Take me to the beach!” But this really is a fascinating book. Each of the original 13 colonies, plus a few other early states, is given its own chapter. From New Jersey (the first and simplest case of disestablishment) to Massachusetts (the last and most complicated) a talented group of scholars detail the political, cultural, and legal process of disestablishment in early America.

2. Robert Letham. Systematic Theology (Crossway). The Reformed world has been blessed with a steady stream of new systematic texts and resources in the past decade. What makes Letham’s stand out is his knowledge of the entire tradition, from the Fathers to the Reformers to contemporary voices. Letham marshals his impressive knowledge in one volume that is clearly organized and written without a lot of technical jargon. This is a book I will consult for years to come.

2. Robert Letham. Systematic Theology (Crossway). The Reformed world has been blessed with a steady stream of new systematic texts and resources in the past decade. What makes Letham’s stand out is his knowledge of the entire tradition, from the Fathers to the Reformers to contemporary voices. Letham marshals his impressive knowledge in one volume that is clearly organized and written without a lot of technical jargon. This is a book I will consult for years to come.

1. Carol V. R. George. God’s Salesman: Norman Vincent Peale and the Power of Positive Thinking (Oxford University Press). Originally published in 1993 and then reissued in a second edition this year (no doubt, because of President Trump’s connections to the Marble Collegiate minister), a biography of Norman Vincent Peale may seem an odd choice for my top 10 list. I don’t agree with Peale’s methodology, priorities, preaching, or theology. But he’s probably the most important 20th-century American religious leader that few think of. Even with something of a Reformed resurgence in recent decades, the reality is that the most popular Christian books, churches, and preachers in this country are still much more like Peale than like Piper. From his trust in the basic goodness of the human mind and heart, to his valuing of experiential and personal faith over doctrine and traditional religion, to his lifelong passion for Republican politics, to his emphasis on health, achievement, and success, Peale not only embodied the spirit of his age, his blending of New Thought philosophy and neo-evangelical ethos also helped shape generations to come.

1. Carol V. R. George. God’s Salesman: Norman Vincent Peale and the Power of Positive Thinking (Oxford University Press). Originally published in 1993 and then reissued in a second edition this year (no doubt, because of President Trump’s connections to the Marble Collegiate minister), a biography of Norman Vincent Peale may seem an odd choice for my top 10 list. I don’t agree with Peale’s methodology, priorities, preaching, or theology. But he’s probably the most important 20th-century American religious leader that few think of. Even with something of a Reformed resurgence in recent decades, the reality is that the most popular Christian books, churches, and preachers in this country are still much more like Peale than like Piper. From his trust in the basic goodness of the human mind and heart, to his valuing of experiential and personal faith over doctrine and traditional religion, to his lifelong passion for Republican politics, to his emphasis on health, achievement, and success, Peale not only embodied the spirit of his age, his blending of New Thought philosophy and neo-evangelical ethos also helped shape generations to come.