Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 11

August 5, 2019

What I Did on My Summer Vacation

I know, long time no blog.

My last blog post was in the middle of June, and since then I spent a week teaching in the UK, spent another week in Dallas at the PCA General Assembly, traveled to Michigan for a week’s vacation, and then spent the rest of the July on study leave. Besides enjoying a lighter pace for the month—which I did: going to the pool with my kids, watching the Tour de France, mowing the lawn, playing games, helping around the house—I had two main projects.

The first project was to prepare my dissertation for publication. I’m pleased that my revised dissertation will be published with Routledge, an excellent British academic press, in the series Routledge Studies in Evangelicalism, edited by Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones. I will be getting the manuscript book-worthy for the next couple months, with an eventual publication date sometime in 2020. Tentative title: The Religious Formation of John Witherspoon.

The second project was at the other end of audience spectrum. I’m working with Crossway on a children’s Bible storybook. The look and feel will be akin to The Biggest Story, but instead of covering the plot line of Scripture in one fell swoop, this will be a 400- to 500-page book with more than 100 Bible stories. I’m thrilled to be working again with the extremely talented Don Clark, who will be providing the artwork to accompany my text. I have finished the Old Testament stories and will be plugging away at the New Testament over the next months, while Don works feverishly to add the artwork to each chapter. The book is scheduled to release at the end of 2020 or beginning of 2021.

I’m excited for both of these projects to see the light of day, though I suspect one will hit a slightly larger audience than the other.

Here are a couple stories to give you a feel for the work in progress.

*****

Chapter 1

And So It Begins (Genesis 1-2)

In the beginning, there was God.

Actually, that’s not quite right. Even before there was a beginning, there was God. He never started. He always has been, always is, and always will be. God is God. And there is nothing else and no one else who compares with him.

God doesn’t get lonely, or bored, or scared. He doesn’t need anything from anyone. He just IS. The great I AM. Whether people know it or not.

But don’t think that makes God a meanie. There is nothing mean about him. God is all love and all glory all the time.

Which is why in the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. God made everything: day and night, land and water, and fruits and vegetables, and sun and moon, and swimming things and flying things, big burly beasts and little creepy-crawlies. In the span of six days, God created our amazing universe. The power and beauty and goodness of our invisible God would now be visible.

Of all the special things God made, the most important thing was not a thing at all. It was a person. God may have been fond of fish, and he probably liked camels and kangaroos too (maybe even spiders!). But he created man in his own image. That’s us! We were made to be pictures of God’s glory—living, breathing statues whose work in the world is to show that this place belongs to God and to tell everyone what he is like.

The first person God made was Adam. He came from the dust of the ground. The second person God made was Eve. She came from Adam’s side. They were both made in God’s image, and they were made for each other. A perfect fit. Just like God had planned. So that husband and wife can be together and make lots of itty-bitty baby image-bearers to fill the earth.

Things were off to a pretty good start. God was so pleased with his creation, he looked around, saw that everything was tremendously terrific, and rested on the seventh day. A perfect beginning to the beginning.

Prayer: Dear God, we love to see all the good things in your creation. Thank you for making this world and for making us to be like you.

*****

Chapter 32

Grime and Punishment (2 Kings 5)

After Elijah didn’t die (but went to heaven all the same) God raised up a new prophet to walk in Elijah’s shoes. His name was Elisha, and he didn’t literally walk in Elijah’s shoes, but he did literally wear Elijah’s cloak and was blessed with a double portion of Elijah’s spirit. He was the next great prophet to speak God’s message and wield God’s power.

And Elisha did a lot of both. As a messenger, he instructed kings, rebuked enemies, and promised food for hungry people. And as a miracle worker he multiplied cooking supplies, purified deadly stew, made an axe head float, and brought the dead back to life.

In those days, Syria was often at war with Israel, and on of their raids they stole a little Israelite girl who would play a big part in God’s plan. The little girl worked for the wife of Naaman, a commander in the Syrian army. Naaman was a mighty man of valor, but he also had a serious skin disease called leprosy. When the little girl learned of Naaman’s disease she spoke up, “You need to see the prophet from Israel!”

So Naaman went with his horses and chariots and stood at the door to Elisha’s house. “Go wash in the Jordan River seven times,” Elisha told him, “and you shall be clean.” You might think this would be good news to Naaman, but it made him furious. “The Jordan River!” he said. “We have better rivers in Syria. I thought this prophet was going to help me!”

As Naaman was leaving, one of his servants urged him to listen to Elisha. So Naaman humbled himself, went down in the water, and dipped himself in the Jordan River seven times. And wouldn’t you know it, the leprosy was gone. Naaman was clean.

Being a rich man, Naaman was prepared to pay for such a miracle, but Elisha refused. He would not take anything from Naaman. The grace God gave Naaman was to be a gift.

But one of Elisha’s servants, a man named Gehazi, thought differently. “I bet I can still get something for this miracle,” Gehazi figured. So he ran after Naaman and took from him two bags of silver and two changes of clothes.

When Gehazi returned, Elisha knew something was not right. “Where have you been?” Elisha asked. “Nowhere,” Gehazi replied. But Elisha saw through the lie. He knew that Gehazi had chased after Naaman. “Because you sought to get rich from God’s grace,” Elisha said, “the leprosy that left Naaman will now stick to you.” Gehazi learned the hard way: there are some gifts money can’t buy, and some money we shouldn’t accept.

Prayer: Forgive us, Lord, when we are greedy. Forgive us even more when we don’t value your grace. Amen.

June 18, 2019

Preaching Resources: A Summer Reading List

As I’ve been preparing to take time off this summer for study and rest, I reached out to some of my friends and colleagues from TGC for advice on books to read on the topic of preaching. I specifically wanted books to help me improve as a preacher—not necessarily how-to books for the beginning preacher (although we need those too), but resources to help seasoned preachers get better. Here are the recommendations I received:

Alistair Begg: 1. Heralds of God by James S. Stewart. Wonderful example of “old school” 20th-century evangelical Scottish preaching. 2. Saving Eutychus by Gary Miller and Paul Campbell. A very practical look at the mechanics—pace, pitch, volume and tone. 3. The Christian Ministry by Charles Bridges. A classic on the context in which preaching takes place.

D. A. Carson: 1. Preaching as the Word of God: Answering an Old Question with Speech-Act Theory by Sam Chan (2016). 2. A Vision for Preaching: Understanding the Heart of Pastoral Ministry by Abraham Kuruvilla (2015). 3. Crossover Preaching: Intercultural-Improvisational Homiletics in Conversation with Gardner C. Taylor by Jared E. Alcántara (2015). 4. Preaching in the New Testament: An Exegetical and Biblical-Theological Study by Jonathan I. Griffiths (2017). 5. Expository Exultation by John Piper (2018). 6. Preaching Christ from the Psalms by Sidney Greidanus (2016).

Steve DeWitt: I’d recommend The Joy of Preaching by Phillip Brooks. Brooks’s book is as relevant today as ever (circa 1800s). He writes as a master-preacher passing on his wisdom to all who will hear and heed his humble example. The church needs more Brooks-style ancient-modern sermons proclaimed and heard with joy.

Dan Doriani: Him We Proclaim by Dennis Johnson.

Collin Hansen: The Religious Affections by Jonathan Edwards. Preaching is motivating Christians in godliness, and I don’t know anyone outside Scripture who understood human motivations and desires better than Edwards.

David Horner: Sometimes we need a taste of “old school,” so I suggest a look back with great promise to On the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons by John Broadus, one of the founders of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Although many of his thoughts are outdated, the basics never go out of style. He can be read with much profit, even for the modern preacher.

Irwyn Ince: 1. If you’d like more exposure to the African American sermonic tradition, I recommend Preaching with Sacred Fire: An Anthology of African American Sermons, 1750 to the Present (Martha Simmons and Frank Thomas, eds). 2. I love Robert Smith’s Doctrine That Dances: Bringing Doctrinal Teaching to Life. 3. Herman Bavinck on Preaching & Preachers (James Eglington, ed.).

Tim Keller: 1. Alec Motyer’s little book Preaching?: Simple Teaching on Simply Preaching. 2. And look around for all the various chapters and essays out there by Sinclair Ferguson. Thinking of his chapters in Logan’s The Preacher and Preaching (“Exegesis”), in Mohler’s Feed My Sheep (“Preaching to the Heart”), and his essay on “Preaching Christ from the Old Testament.”

Julius Kim: If I can be so bold as to recommend my own book—Preaching the Whole Counsel of God is a primary textbook on the art and science of preaching for pastors and pastors-in-training that teaches you how to practice expository, Christ-focused hermeneutics, combined with gospel-centered, audience-transforming homiletics. It will guide you to: Discover the truth of the text according to the human author, Discern Christ in the text according to the divine author, Design your sermon with truth, goodness, and beauty, and Deliver your sermon in a way that keeps attention, retention, and leads to transformation.

Bill Kynes: This summer my associate pastor and I will be reading Let the Earth Hear His Voice by Greg Scharf. Greg has recently retired as professor of pastoral theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and in this book, he offers strategies for overcoming eight common bottlenecks in preaching. The book addresses beginning and seasoned preachers who want to overcome deficiencies that often hinder our effectiveness.

Ray Ortlund: I recommend the essay by Francis Schaeffer entitled “Two Contents, Two Realities,” included as an appendix in the book 25 Basic Bible Studies. Schaeffer gives us preachers the categories we need to shape our preaching and pastoring in such a way that we might, by God’s grace, for God’s glory, compel the attention of this generation. I firmly believe that nothing less will suffice.

Vermon Pierre: The only one I think I would mention right now would be Preaching with Sacred Fire: An Anthology of African American Sermons, 1750 to the Present (Martha Simmons and Frank A. Thomas, eds.). This is more for those who want a resource on primary sources on this to interact with thoughtfully. This is not necessarily an endorsement of every sermon in the volume! Indeed, the better sermons are at the beginning, featuring people like Lemuel Haynes and John Murrant and Richard Allen. I would recommend this volume more for those who are students of and practitioners of preaching who want to understand preaching as understood not just within their own theological tribe but beyond that.

Harry Reeder: 1. Preaching and Preachers by Martyn Lloyd-Jones—for conscience sake I have to recommend that book first and foremost. 2. Although he left his original premise, one of the older books by Haddon Robinson—Biblical Preaching—I found extremely helpful. 3. The one I would highlight since the two mentioned have probably been considered would be Preaching with Purpose by Jay Adams. His focus upon the “telos” of the text was ahead of the time for the “big idea” preachers of today. 4. Another book Jay Adams wrote on preaching was an analysis of the sermons of Charles Haddon Spurgeon called Sense Appeal in the Sermons of Charles Haddon Spurgeon. 5. Spurgeon’s Lectures to My Students and An All-Round Ministry are two more.

Philip Ryken: Godric by Frederick Buechner—inspiring short read, historical fiction on the life of a true gospel saint, worth reading also for its rich use of language and dynamic storytelling.

Tim Savage: What I’ve found most helpful in developing preaching content and delivery is reading the sermons of great preachers, especially those of Edwards, Spurgeon, and Lloyd-Jones. Pairing sermons with stellar biographies or autobiographies of these preachers (Marsden, Spurgeon, and Murray) has taught me more about preaching than I’ve received from other sources.

David Short: John Owen’s The Glory of Christ. It is an absolute feast.

Sam Storms: Piper’s Expository Exultation is the best book on preaching I’ve ever read.

Stephen Um: Schnabel’s work on the book of Acts (Paul, the Missionary) has been helpful, especially in pointing out Paul’s apologetic approach in speaking to a secular audience in Lystra (Acts 14) and Athens (Acts 17). He develops the idea of the “element of contact” and the “point of contradiction.” But what is helpful is that he points out that Paul engaged in apologetic judo when he used the “element of contact” as the “element of contradiction.”

June 13, 2019

Distinguishing Marks of a Quarrelsome Person

Quarrels don’t just happen. People make them happen.

Of course, there are honest disagreements and agree-to-disagree propositions, but that’s not what the Bible means by quarreling. Quarrels, at least in Proverbs, are unnecessary arguments, the kind that honorable men stay away from (Prov. 17:14; 20:3). And elders too (1 Tim. 3). These fights aren’t the product of a loving rebuke or a principled conviction. These quarrels arise because people are quarrelsome.

So what does a quarrelsome person look like? What are his (or her) distinguishing marks? Here are twelve possibilities.

You might be a quarrelsome person if . . .

1. You defend every conviction with the same degree of intensity. There are no secondary or tertiary issues. Everything is primary. You’ve never met a hill you wouldn’t die on.

2. You are quick to speak and slow to listen. You rarely ask questions and when you do it is to accuse or to continue prosecuting your case. You are not looking to learn, you are looking to defend, dominate, and destroy.

3. Your only model for ministry and faithfulness is the showdown with the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel. Or the only Jesus you like is the Jesus who cleared the money changers from the temple. Those are real examples in Scripture. But the Bible is a book, and sarcasm and whips are not the normal method of personal engagement.

4. You are incapable of seeing nuances, and you do not believe in qualifying statements. Everything in life is black and white without any gray.

5. You never give the benefit of the doubt. You do not try to read arguments in context. You put the worst possible construct on other’s motives, and when there is a less flattering interpretation you go for that one.

6. You have no unarticulated opinions. Do people know what you think of everything? They shouldn’t. That’s why you have a journal or a prayer closet or a dog.

7. You are unable to sympathize with your opponents. You forget that sinners are also sufferers. You lose the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes.

8. Your first instinct is to criticize; your last instinct is to encourage. Quarrelsome people almost always see others in need of rebuke, rarely in need of refreshing.

9. You have a small grid, and everything fits in it. You view life through a tiny prism such that you already know what everything is about. Everything is a social justice issue. Everything relates to the regulative principle. Everything is Obama’s fault. Everything is about Trump. It’s all about the feminists. Or the patriarchy. Or how my parents messed up my life. When all you have is a hammer, the rest of the world looks like a nail.

10. You derive a sense of satisfaction and spiritual safety in feeling constantly rejected. We don’t want to blame the victim, but some people are constitutionally unable to exist except as a remnant. They must be persecuted. They must be maligned. They do not know how to live in peacetime, only in war.

11. You are always in the trenches with hand grenades strapped to your chest, never in the cafeteria with ice cream and ping pong. I remember years ago talking to a returning serviceman in my church who told me sheepishly that his job in Iraq was to drive an armed convoy for the ice cream truck. It was extremely dangerous, escorting the vehicle through bomb infested territory. This was brave, honorable work. And important: Even soldiers need ice cream once in a while. The amp doesn’t have to be cranked to 11 all the time. Seriousness about God is not the same as pathological seriousness about everything. Remember G. K. Chesterton: “We have to feel the universe at once as an ogre’s castle, to be stormed, and yet as our own cottage, to which we can return to at evening.”

12. You have never changed your mind. If you haven’t changed your mind on an important matter in several presidents, I wonder if you are a Christian or even alive. Of course, truth never changes, and neither should many of our convictions. But quarrelsome people stir up strife because, already knowing everything, they have no need to listen, learn, or ask questions.

Hit close to home? Look to Christ. He has the power to change us and has made provision to forgive. By the death of the Prince of Peace we can be at peace with God and at peace with one another.

June 8, 2019

Remembering David Powlison

He was a prince of a man.

That’s what I keep telling people. It’s customary to say laudatory things about a person upon his death, whether there was all the much to laud or not. With David Powlison there is plenty to come. Other tributes have come in, and I’m sure there are many more to follow. Here are my paltry two pennies.

I met David around ten years ago, having read his articles and books for years before that. Some people are very different in person than what you might expect. David was exactly as I imagined him to be: warm, engaging, inquisitive, humble, forthright, gracious, and wise.

Yes, lots of wisdom, as you might expect from the man who pioneered the biblical counseling movement. We were at a TGC meeting in Chicago when I first spent time with David. Selfishly, during a dinner break I found the van David would be riding in so I could spend a few hours with the man I had already learned so much from. I wasn’t the only one in the van or the only one at dinner. Several of us asked him questions about counseling, about pastoral ministry, and about issues in our own lives. Except for our questions, David talked almost the entire time. It was one of the few times I can remember in life where someone dominated hours of conversation as an act of humility. At one point he meandered into a long series of reflections on the Sermon on the Mount. It was masterful. He was a master at Spirit-filled rumination.

Over the ensuing years our paths would cross from time to time–at a conference, at Westminster, at TGC, over the phone. He was always warm with a smile and wise with his words. He understood people and understood his Bible. He asked great questions and told great stories. He was tender enough to care for souls effectively and bold enough to reprove those who didn’t.

A few weeks ago I sent an email to the TGC council asking for recommended preaching resources (hopefully I’ll turn that into a blog soon). All I asked for was an author, a book, and a sentence of recommendation. Aware of David’s declining health, I never expected him to reply. But he did. And what he wrote was pure gold (and pure Powlison), not really a direct answer to my question, but a brief reflection on the nature of preaching itself.

From David Powlison on May 23:

I have thought for a long time that the biggest lack among preachers who love God’s Word is that they don’t know people well enough. So they dive deep into exegesis and biblical theological exposition, and theological categories, but their applications come down (far too often) only as far as generalizations, moralism, pietism, or how to stand up against cultural falsehoods. A true moral goodness, a candid piety where real need connects to real promises (like the psalms), and standing against cultural drift all matter profoundly. But generalizations need to be brought down to street level struggles and to self-deceptive habits of the heart. Truly effective, life-altering preaching — like all real personal engagement with Scripture — is based on what Paul Tripp called the “double exegesis”: honest human experience meets deeply understood biblical truth. Books to read? I’m biased toward CCEF naturally, where our practical theology labors hard to do both!

A few weeks prior, the TGC council gathered after the national conference. David wanted to be there, but his ill health prevented him. He wrote a letter to us–a touching, Christ-stained letter which he asked his good friends Tim Keller and Ray Ortlund to read. It was surreal to hear David address us as a body for the last time. And yet, even in that farewell letter he ministered to us, encouraged us, called us to Christ and pointed to the cross. It’s what David did and who he was. Without exaggeration I can say that I walked away from every encounter with David wanting to know God more and love people better. It’s hard to leave a more impressive legacy. Soli Deo gloria.

June 4, 2019

Book Briefs

Lots of books to catch up on. Here’s some of what I’ve been reading in the last couple months.

Matthew Barrett, None Greater: The Undomesticated Attributes of God (Baker Books, 2019). Barrett continues to crank out excellent theological material. This latest offering provides a classic exposition of simplicity, immutability, and the rest of God’s attributes.

Herman Bavinck, The Sacrifice of Praise (Hendrickson, 2019). This “new” book—translated and edited by Cameron Clausing and Gregory Parker Jr., with a foreword by Scott Swain—is full of biblical wisdom and deep spirituality. These penetrating reflections on baptism, communion, and confession will help parents, children, educators, pastors, students, new Christians, and seasoned saints alike.

Alistair Begg, Pray Big: Learn to Pray Like an Apostle (Good Book Company, 2019). Prayer is so important, and so difficult, that we always need more good books on prayer. Alistair writes with a biblical simplicity and pastoral sincerity that will help you not just feel like you should pray, but feel that you can.

Robert A. Caro, Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Alfred A. Knopf, 2019). Fascinating from start to finish. I confess I have not read all (or most) of Caro’s famous work on LBJ, but I have read enough to know that as a researcher and political biographer, he has no equal. This little book is a snapshot into the subjects of his big biographies—Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson—as well as a glimpse into the method behind Caro’s own madness.

Marc Cortez, Theological Anthropology: A Guide for the Perplexed (T&T Clark, 2010). Here you’ll find complex ideas clearly organized and articulately communicated. I can’t say I agreed with all of Cortez’s arguments; in general, I agreed with less as he moved through the book. Calvinists in particular will land in a different place on the freedom of the will. But all in all, a good introduction to a growing and important field.

J. V. Fesko, Reforming Apologetics: Retrieving the Classic Reformed Approach to Defending the Faith (Baker Academic, 2019). Within the Reformed community, I predict this will be one of the most important theological works of the last several years. Fesko does not seek to refute presuppositional apologetics so much as he makes the convincing case that Van Til’s approach to defending the faith is not adequate by itself. The main point: “There is a general distrust of natural theology. I hope to present evidence that would make people reconsider their aversion to its use in theology and apologetics” (xii). Fesko argues that the book of nature sits on the shelf unused, when Reformed theologians and practitioners should not be afraid to use it.

Adam Gopnik, A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure in Liberalism (Basic Books, 2019). I was hoping for a historical account of the development of the classic liberal tradition in politics. While Gopnik does some of that, his account of the liberal tradition looks largely like a defense of contemporary liberalism. He does critique both the left and the right, but the right means conservative Christians while the left means Marxism. Middle ground? The sensibilities of people who read The New Yorker.

Kevin Harney, Organic Outreach for Ordinary People: Sharing Good News Naturally (Zondervan, 2009). Books on evangelism are like books on prayer: We always need more of them because most of us are so bad at both. In this book from 10 years ago, Harney tries to make evangelism more natural and less intimidating.

Paul Helm, Human Natures from Calvin to Edwards (Reformation Heritage Books, 2018). A dense book about a dense subject, but still an impressive survey for professors, pastors, or advanced students who want to mine the Reformed tradition as it relates to human nature, faculty psychology, morality and agency.

Michael Hyatt, Free to Focus: A Total Productivity System to Achieve More by Doing Less (Baker Books, 2019). Like I’ve said before, I am constantly reading books on priorities and productivity, not because I’m an expert but because my life demands that I say no to lots of things. Of course, the title oversells. This will not change your life in five easy steps, but Hyatt has a lot of good ideas worth implementing. The gist: You aren’t focusing on what you’re good at, and you should be.

John F. Kilner, Dignity and Destiny: Humanity in the Image of God (Eerdmans, 2015). A work on the doctrine of the imago dei that manages to be up to date without being novel. Kilner argues that the image of God is about God’s intention for humanity. The imago dei has to do with our connection with God through covenant and our reflection of God as the crowning glory of his creation. In many ways, then, the imago dei is a placeholder, a “hermeneutical lens” through which we can understand history and make sense of where we are headed and what we are supposed to be (39-40).

Timothy Larsen and Michael Ledger-Lomas (eds), The Oxford History of Protestant Dissenting Traditions, Volume III: The Nineteenth Century (OUP, 2017). This is a terrific (and expensive!) series. The book is attractively designed and brings together an impressive array of scholars writing about the Protestant non-Anglican traditions that emerged in the British Empire.

Robert Tracy McKenzie, A Little Book for New Historians: Why and How to Study History (IVP Academic, 2019). A short book that delivers much more wisdom than its size suggests. Whether you are a trained historian, an interested student, or merely a fan of history, you will find this book illuminating. Two major takeaways: Doing history is an exercise in loving our neighbors, and history is always complicated.

Noah Rothman, Unjust: Social Justice and the Unmaking of America (Regnery Gateway, 2019). As a writer for the conservative Jewish periodical Commentary, one would expect Rothman to be critical of social justice warriors, which he is. But this is not a right-wing hit piece. It’s more like an extended essay chronicling the ways in which some advocates of social justice end up undermining basic tenets of civility and the classic Western liberal tradition. His examples are real and often alarming. On the other hand, critics will surely point out that Rothman has not highlighted the positive contributions of those who are concerned with social justice.

May 28, 2019

Central Carolina Presbytery Study Committee Report on 2018 Revoice Conference

On November 13, 2018, the Central Carolina Presbytery (PCA) formed an Ad-Interim Study Committee “to explore the 2018 Revoice Conference and to report its findings to Central Carolina Presbytery and recommend any action that the Presbytery might take.” In keeping with the Presbytery’s instructions, the Moderator appointed seven members and one alternate to serve on the committee.

The report was approved unanimously by the Study Committee and sent to the Presbytery. At today’s meeting, the Central Carolina Presbytery received the committee’s report (linked at the bottom of this post) and voted to “commend the report to the churches and the denomination.”

Here is the report’s conclusion:

As members of the body of Christ we don’t get to choose the controversies of our age. We might prefer to be talking about the Trinity or the two natures of Christ—and we should talk a lot about both doctrines—but the fact is that if we are going to be faithful as pastors, as Christians, and as a denomination we cannot avoid talking about sexuality. Sexual identity is one of the main sources of confusion and contention in our world—a reality that likely will not change in our lifetimes. We must find a way to navigate these issues that is biblically sound, theologically robust, historically informed, linguistically careful, relationally compassionate, and pastorally wise.

This means we must be a people committed to truth. We appreciate Revoice’s commitment to biblical marriage. We commend them for their desire to help sexual strugglers stay rooted in Christ and in historic orthodoxy. At the same time, we are concerned that some of the principal voices in Revoice have not been careful enough with their labels, their theology, and their relational advice. Consequently, at present we do not feel Revoice is a safe guide in helping Christians navigate questions of gender and sexuality. We hope that within the PCA more attention will be given to the theology expressed in our Standards and to the doctrinal precision exemplified in the best of our tradition. We worry at times that some have traded a Reformed doctrine of sin for a therapeutic understanding of brokenness, or even for a Roman Catholic understanding of concupiscence. With a diminished view of sin comes a diminished role for repentance, a diminished understanding of the power of the gospel, and ultimately a diminished experience of worship itself. In a day where emoting comes easier than thinking, we must renew our conviction that truth does not get in the way of helping people; truth is fundamentally necessary if we are to be truly helpful.

Of course, truth is not all we must keep in view when thinking through these difficult issues. We must never forget that we are dealing with real people, flesh and blood human beings with hurts and fears and joys and hopes. While we disagree with important aspects of what was said and assumed at the Revoice Conference, in so far as the movement acts as a reminder for all of us to be welcoming, sympathetic, and hospitable, there are valuable things we can learn and necessary lessons to be appropriated. In the end, just as the Son came from the Father full of grace and truth, so we pray that we do not have to choose between the two. The same-sex attracted among us need what all of us need, and what can only be found in the church: the redeeming power of gospel truth and the transformational love of gospel people.

The entire 16-page report can be found here: Central Carolina Revoice Report.

May 27, 2019

Why Christians Should Give Thanks for Memorial Day

Memorial Day, originally called Decoration Day, was instituted to honor Union soldiers who died in the Civil War. After World War I, the purpose of the day was expanded to include all men and women who died in U.S. military service. Today, Memorial Day is often thought of as the unofficial start of summer–a long weekend with a car race, playoff basketball, and brats and burgers on the grill.

It is always tricky to know how the Christians should or shouldn’t celebrate patriotic holidays. Certainly, some churches blend church and state in such a way that the kingdom of God morphs into a doctrinally-thin, spiritually nebulous civil religion. But even with this dangers, there are a number of good reasons why Christians should give thanks for Memorial Day.

1. Being a soldier is not a sub-Christian activity. In Luke 3, John the Baptist warns the people to bear fruit in keeping with repentance. The crowds respond favorably to his message and ask him, “What then shall we do?” John tells the rich man to share his tunics, the tax collectors to collect only what belongs to them, and the soldiers to stop their extortion. If ever there was a time to tell the soldiers that true repentance meant resigning from the army, surely this was the time. And yet, John does not tell them that they must give up soldier-work to bear fruit, only that they need to be honest soldiers. The Centurion is even held up by Jesus as the best example of faith he’s seen in Israel (Luke 7:9). Military service, when executed with integrity and in the Spirit of God, is a suitable vocation for the people of God.

2. The life of a soldier can demonstrate the highest Christian virtues. While it’s true that our movies sometimes go too far in glamorizing war, this is only the case because there have been many heroics acts in the history of war suitable for our admiration. Soldiers in battle are called on to show courage, daring, service, shrewdness, endurance, hard work, faith, and obedience. These virtues fall into the “whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just” category that deserve our praise (Philippians 4:8).

3. Military service is one of the most common metaphors in the New Testament to describe the Christian life. We are to fight the good fight, put on the armor of God, and serve as a good soldier of Christ Jesus. When we remember the sacrifice, single-minded dedication, and discipline involved in the life of a soldier, we are calling to mind what we are supposed to be like as Christians in service to Christ.

4. Love of country can be a good thing. As Christians we have dual citizenship. Our first and ultimate allegiance must always be to Christ whose heavenly dwelling is our eternal home. But we are also citizens of an earthly country. We will stand before God not as individuals wiped clean of all earthly nationality, but as people with distinct languages, cultural affinities, and homelands. It is not wrong to love our distinct language, culture, or nationality. Whenever I’m at a ball game I still get choked up during the singing of the National Anthem. I think this is good. Love for God does not mean we love nothing else on earth, but rather that we learn to love the things on earth in the right way and with the right proportions and priorities. Love of country is a good thing, and it is right to honor those who defend the principles that make our country good.

5. I believe the facts of history will demonstrate that on the whole, the United States military has been a force for good in the world. Obviously, as a military power, we have blundered at times, both individually and corporately. But on the whole, the men and women of our armed services have fought and are fighting for causes that promote freedom, defend the rights of human beings, and reject tyranny. War is still hell and a tragic result of the fall. Praise God for his promise to one day end all human conflict. But in a world where people are evil by nature and leaders are not always reasonable and countries do not always have good intentions, war is sometimes the way to peace-at least the best peace we can hope for between peoples and nations this side of heaven.

So thank God for a day to remember God’s common grace to America and his special grace in enlisting us, poor weak soldiers that we are, in service to Christ our Captain and conquering King.

May 21, 2019

Cautious about Causation

In the social sciences, one learns quickly (or is supposed to learn) that correlation does not equal causation.

I remember learning in driver’s training the scary statistic that most accidents happen within a few miles from home. The takeaway for us young drivers was obvious: People are careless when driving in familiar places, so be careful! But of course, this takeaway equates correlation (the number of accidents linked to the distance from home) with causation (we must drive worse because we are close to home), when a better explanation is that most of our driving naturally takes places within a few miles of home, so that’s where most of our accidents are bound to happen.

Just because two things are co-related does not mean one is the cause of the other or that the link between the two is clear or necessary.

No Straight Line

In 2001, David Powlison published a brilliant article entitled The Ambiguously Cured Soul. It was about a married woman named Amelia who struggled with lesbian fantasies. Through Christian counseling, Amelia “discovered” that her attraction to women was due to her past: Because she had an abusive father and a distant mother, Amelia was repelled by men and longed to find emotional connection with a woman. As helpful as the counseling may have been in one respect, Powlison argued that the causal narrative was misplaced. Any number of scenarios might have followed from Amelia’s upbringing. As Justin Taylor summarizes, “the counselee might live an immoral heterosexual lifestyle because of her longing for an intimate relationship with men; she might marry a man just like her dad because she’s drawn to that which hurt her; she might isolate herself from the world since she can trust no one; she has a godly marriage having determined to avoid her parents’ mistake.”

Of course, understanding our pasts can be useful in making sense of the present. But it’s a deterministic myth to think, “I had to turn out this way.” The fact of the matter is, there is no straight line whereby certain experiential inputs invariably lead to the same set of lifetime outputs.

What Hath Culture Wrought?

What’s true in counseling is true in tragedies too.

All of us in the Reformed world were shocked and saddened to learn that the alleged Ponway Synagogue shooter was “one of us,” a theologically minded young man who belonged to an OPC congregation. Without a doubt, this is an occasion to reflect on whether any of us have been soft on anti-Semitic hatred or if any of our churches are breeding grounds for murderous angst.

And yet, by all accounts, the parents and the pastor have said the right things and seem to be the sort of people that manifestly did not create a killer. If there is any causal link it is with the radicalization that happens in apocalyptic communities on message board sites like 8chan. Just because the shooter may have stolen evangelical language or Reformed theology to make his point does not mean the Christian faith is to blame any more than Jesus was to be blamed when his disciples wanted to call down fire on the Samaritans in order to defend his honor (Luke 8:51-55). The key is that Jesus rebuked them, and so must we when we see people under our care twist our teachings or when we witness their zeal turning to violence.

In our age of political polarization, we often hear accusations—on both sides—that Tragedy A was the result of a “culture of hate” or that Horrible Atrocity B was the product of “good people saying nothing.” I suppose those arguments can be true, but as a rule they are almost always so nebulous as to be unprovable and so universal as to be non-falsifiable. If millions of people in the same “culture” never act out in violent ways and a very, very, very small number do, how effective is the culture anyway?

Again, I’m not suggesting that families or religious communities or broader societal factors never play a role—and sometimes it can be shown that they play a significant role—but as a stand-alone argument, we should shy away from “the culture” as a causal explanation for much of anything. It’s unfortunate that some of the same academics who look for finely tuned, always qualified nuances in making arguments about the past are quick to make sweeping causal claims when it comes to analyzing the present.

It’s Complicated

Which brings me to a final point, and this may be the most controversial. I believe one of the impediments (and there are many!) in discussing racial issues in this country is that too many of us gravitate toward simplistic mono-causal explanations for amazingly complex phenomena. The uncomfortable fact is that there are wide disparities between blacks and whites when it comes to a host of well-being measurements, from standardized test scores to educational attainment to household income to rates of incarceration. If some are quick to explain these disparities based on merit and hard work, others are quick to assume that discrimination and white supremacy are to blame. I’ve always found the easy explanations to be unhelpful—unhelpful in understanding the present and unhelpful in making things better in the future. It’s not discounting the legacy of racism or the value of personal responsibility to argue that neither is a sufficient explanation (nor an irrelevant consideration) for why people have what they have and are what they are.

People are complicated, and history is complicated. We don’t do anyone any favors by pretending that people or the past can be understood and summed up in a single, unifying theory. Like you, I am—under God’s sovereignty—the product of genes and family and friends and schools and peers and churches and books and experiences and unspoken assumptions and unwritten rules and (for me, a lot of) undeserved opportunities and (for me, fewer) undeserved obstacles and a million personal choices along the way. All of us have reasons to be humble about what we have and are, and all of us have reasons to be cautious about our theories of causation.

Only God knows fully how all the pieces fit together. Only God knows how everything led to everything. Only God knows what complete cosmic justice looks like. This is no excuse for intellectual laziness. Some explanations are better than others. But it means we should not fall into the intellectually lazy, but rhetorically effective trap of thinking that people and problems of the present are simply the result of the perfect mix of ingredients from the past.

May 14, 2019

Were the First Christians Socialists?

No.

Now that we’ve gotten that anwer out of the way, let me offer an important caveat. In arguing that the first Christians were not socialist (or communist for that matter), I am not supposing that they championed an early version of Hayek’s economic views and would have formed the first Cato Institute if given the chance. We should not make the Bible say more than it means to say, and that means that if we want to argue for the rightness of free-market capitalism we’ll have to do so based on something other than direct scriptural obligation.

It also means that we should not make the book of Acts into a precursor to the Communist Manifesto.

Here are the two passages most often used to suggest that the early church was socialist or communist.

And all who believed were together and had all things in common. And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need. (Acts 2:44-45)

Now the full number of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one said that any of the things that belonged to him was his own, but they had everything in common. . . . There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were owners of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold and laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need. (Acts 4:32, 34-35)

Let’s set aside that socialism and communism are not identical, socialism being for Lenin a distinct stage between capitalism and communism. In broad terms, we could say that socialism implies social ownership of the means of production, while communism also insists upon an equitable and shared consumption of that production. In popular parlance (in America at least) communism still sounds bad to most people, but socialism is increasingly celebrated and defended. What contemporary proponents of socialism usually have in mind is not the ideas of Charles Fourier or Eugene V. Debs, but rather a rhetorical nod in the direction of strong government intervention into the economy and a redistribution of wealth that ensures no one has too little (and no one has too much).

Toward that end, you’ll often hear people point to the book of Acts as an example—to quote a recent tweet from a Member of the Scottish Parliament–of “outright socialistic redistribution amongst the first followers [of Jesus].”

At first glance it can look like the first-century church modeled an early form of socialism. After all, “they had everything in common.” Maybe Marx was just reading his Bible when he argued, “From each according to his ability; to each according to his need.” Isn’t that what’s going on in the early church? Later in Acts 11:29 we read, “So the disciples determined, everyone according to his ability, to send relief to the brothers living in Judea.” That sounds a lot like a big social safety net and redistribution along socialist lines.

Despite the initial plausibility of a socialist reading of Acts, there are at least two realities that make the sharing in the early church different from socialism and especially communism.

First, there is no evidence that the first Christians shared in the means of production and no record that they abolished private property. We see nothing like a workers collective, let alone state-run enterprises in the book of Acts. The Christians were generous, but they did not disavow personal ownership of their possessions. To be sure, we see Christians selling their land and houses in order to provide for the needy (Acts 4:34, 37). And yet, as Acts 5:4 makes clear, these assets remained in possession of private owners and could be used as the owners saw fit. Even after properties were sold, the proceeds belonged to the individual or family, not to the state, nor to a collective, nor even to the church. This is confirmed in the history of the early church as we see congregations meeting in private homes and persons still in possession of private property (Acts 16:15).

Second, the distribution of possessions in Acts was not by force or coercion, but chosen freely and voluntarily. To say the church had a wonderful communal spirit is far different from saying they practiced anything remotely like state-enforced communism. The expression “everything in common” was used to describe radical generosity in the early church. Sharing in the church was and is a clear sign of the in-breaking of the kingdom (1 John 3:16-17). But nowhere in the New Testament do we see the church embody or support a practice that forces wealth redistribution at penalty of church-run discipline or penalty of the state-run sword. “Everything in common” spoke to the love of the Christians, not to a law among the Christians.

One last thought in closing: When it comes to political prescriptions—from the left or from the right—we must insist as Christians on closer inspection of actual biblical texts. This doesn’t mean natural law has no place in our discussion or that we can’t argue from principles to practice. But it does mean that where we are talking about issues of economics or justice or race or whatever, we cannot settle for soft slogans and big themes. We have to get into the text and make our case from Scripture. And if we can’t make our case directly from Scripture—and often we won’t—let us be honest enough to make clear that we are basing our arguments, at least in part, on prudential considerations, history, social science, or other factors.

April 30, 2019

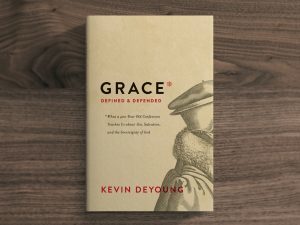

The Canons of Dort and the Gift of Faith

This year is the 400th anniversary of the Synod of Dort. In fact, last Monday marked the exact date, 400 years ago, that the canons were officially approved. If you want to know more about the history and theology of Dort, I have a new book entitled Grace Defined and Defended: What a 400-Year-Old Confession Teaches Us About Salvation, Sin, and the Sovereignty of God. You can go to Crossway to get more information about the book, including endorsements and table of contents. The book is also available for purchase at Amazon and WTS Books.

To give you a feel for the book, I’ve excerpted a section on irresistible grace and the gift of faith.

*****

Imagine two different scenarios and two different gifts.

In scenario one, your father comes home from work on your 16th birthday and announces he has a surprise for you. He takes you to the local car dealership and points to a brand new, sporty convertible. He tells you the car is yours if you want it. He’s paid for it and signed all the papers. All you have to do is grab the keys, hop in the car, and drive your shiny new vehicle off the lot. That’s quite a gift: a pricey convertible for free, if you decide you want it.

Here’s another scenario. You are lying unconscious on a hospital bed. You don’t know where you are, who you are, or what is going on. You should be dead. In fact, the doctor pronounced you dead a minute ago, but now your heart is beating. The hospital staff pumped blood into your veins when you had bled out from a massive laceration on your leg. That’s quite a gift: someone else’s blood for free, put into you when you had no ability to ask for it, resist it, or receive it.

No analogy is perfect, so don’t read spiritual significance into every detail. Don’t focus on the value of the gift (Arminians believe that God gives new life, not new cars) or whether the recipient is dead or alive (though that’s important on another level). Think instead about the nature of the gift. Both are freely given. Both are undeserved. But one gift is presented for you to accept, while the other gift is a new quality infused within us. The gift, as represented in these scenarios, is not salvation per se, but faith. Is saving faith a gift that we can accept or deny, or is it a new principle worked in us by God’s sovereign and unfailingly effectual will? That question is at the heart of Dort’s Third and Fourth Main Points of Doctrine.

It would be unfair to say that the Arminians did not believe in human depravity and divine grace. Like the Calvinists at Dort, the Arminians taught that men and women need the Spirit’s work in their lives in order to exercise faith and repentance. The difference lies in how both sides understood the Spirit’s work in conversion. The Arminians maintained that all people have been given sufficient grace for faith and conversion. Faith is a gift offered to all, but unilaterally infused in none.

By contrast, Dort says we need more than enlightening or enabling grace. God doesn’t affect conversion by mere “moral persuasion” (Rejection VII). Rather, he “penetrates into the inmost being, opens the closed heart, softens the hard heart, and circumcises the heart that is uncircumcised.” In other words, God “infuses new qualities into the will, making the dead will alive, the evil one good, the unwilling one willing, and the stubborn one compliant.” We believe because God unilaterally changes the human heart so that we can and will believe.

When the Arminians defended their view of conversion at Dort, they highlighted our need for divine grace, but they called it a “preceding or prevenient, awakening, following and cooperating grace” (Opinions, C.2). This is why the Arminians denied “irresistible” grace. “Man is able of himself,” they maintained, “to despise that grace and not to believe” (Opinions, C.5).

What then can we do to be regenerated? By Dort’s logic, that is the wrong question. We “cannot fully understand the way this work occurs” (Art. 13). We cannot make ourselves be born again, just as we cannot make ourselves be born (John 1:12-13). We do not work for the miracle of regeneration. That would be a contradiction in terms. Our part is to “rest content with knowing and experiencing” the new birth, being assured that if we “believe with the heart and love the Savior” we have been regenerated. “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8).

While we must exercise faith as an act of the will, faith “is a gift of God, not in the sense that it is offered by God for people to choose, but that it is in actual fact bestowed on them, breathed and infused into them” (Art. 14). This brings us back to the two scenarios at the opening of the chapter. Faith, according to Dort, is not like the car we have to drive off the lot, but like the blood transfusion poured into our veins when we were utterly helpless to help ourselves. In other words, faith is not something outside of us that we grab hold of. It is a work that God works in us, producing “both the will to believe and the belief itself” (Art. 14).