Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 17

February 21, 2018

February 19, 2018

The Missing Word in Our Modern Gospel

Every Christian loves the gospel. By definition, you cannot have a Christian who isn’t shaped by and saved by the gospel.

So three cheers for the gospel. Make that three million cheers.

But let’s preach the gospel the way Jesus and the Apostles did. Theirs was not a message of unconditional affirmation. They showed no interest in helping people find the hidden and beautiful self deep inside. They did not herald the good news that God likes you just the way you are.

Too much “gospel” preaching sounds like a slightly spiritualized version of that old Christina Aguilera song:

You are beautiful no matter what they say.

Words can’t bring you down.

You are beautiful in every single way.

Yes, words can’t bring you down.

So don’t bring me down today.

I don’t doubt that many of us feel beat up and put down. We struggle with shame and self-loathing. We need to know we can be okay, even when we don’t feel okay. It is good news to hear, then, that God loves us in Christ and that we are precious in his sight.

But the gospel is more than positive self-talk, and the gospel Jesus and the Apostles preached was more than a warm, “don’t let anybody tell you you’re not special” bear hug.

There’s a word missing from the presentation of our modern gospel. It’s the word repent.

Yeah, I know, that sounds old school, like an embarrassing sidewalk preacher with a sandwich board and cheap tracts with bad graphics and lots of exclamation points. And yet, even a cursory glance at the New Testament demonstrates that we haven’t understood the message of the gospel if we never talk about repentance.

When John the Baptist prepared the way of the Lord, he preached repentance (Matt. 3:8, 11), just as Jesus launched his Galilean ministry by preaching, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt. 4:17). Jesus understood the purpose of his ministry to be calling sinners to repentance (Luke 5:32). Just before his ascension, the resurrected Christ implored the disciples to be his witnesses, that “repentance for the forgiveness of sins” would be preached in his name to all nations (Luke 24:47). In fact, if there is a one sentence summary of Jesus’ preaching, Mark gives it at the beginning of his Gospel: “Now after John was arrested, Jesus came into Galilee, proclaiming the gospel of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel'” (Mark 1:14-15).

Notice that pair: repent and believe. The two are virtually synonymous in the New Testament, not that the words mean the same thing, but that they are signs of the same Spirit-prompted work and lead to the same end times inheritance. Strictly speaking, the proper response to the gospel is twofold: repent and believe (Matt. 21:32; Acts 20:21). If only one item in the pair is mentioned–which happens often in the New Testament–we should realize that the other half is assumed. You can’t really believe without also repenting, and you haven’t really repented if you don’t also believe.

The gospel message is sometimes presented as a straightforward summons to repent (Acts 3:18-19). Other times, forgiveness is linked to a singular act of repentance (Acts 5:31; Rom. 2:4; 2 Cor. 7:10). The message of the apostolic good news is that God will be merciful when we repent and that repentance leads to life (Acts 11:18). Simply put: repent, that your sins may be wiped out (Acts 3:19).

If the call to repentance is a necessary part of faithful gospel preaching, then maybe we don’t have as much of it as we think. The summons to turn from sin, die to self, and turn to Christ is what is missing from prosperity preachers, from preachers in step with the sexual revolution, and from not a few gospel-centered preachers, too. It’s certainly missing from most of our worship services which long ago did away with a deliberate confession of sin.

To be sure, we aren’t called to beat people up Sunday after Sunday. Many folks stumble into church in desperate need of the Balm of Gilead. I get that. I think anyone who listens to several weeks of my sermons will hear that I’m not a finger-wagging scolder. And yet, if I never call people, with God’s authority, “to be genuinely sorry for sin, to hate it more and more, and to run away from it” (Heidelberg Catechism Q/A 89), then I’m not doing the work a gospel preacher should do.

The unpopular fact remains that the ungrateful and impenitent will not be saved (1 Cor. 6:9-10; Gal. 5:19-21; Eph. 5:1-20; 1 John 3:14). The New Testament has nothing to say about building the kingdom, but it does have everything to say about how we can enter into the kingdom. The coming of the King is only good news for those who turn from sin and turn to God.

If we want to give people a message that saves, instead of one that only soothes, we must preach more like Jesus and less like our pop stars.

February 13, 2018

Marriage Tune Up: Five Books, Five Questions

Tomorrow is Valentine’s Day, which means husbands will be scrambling for babysitters, flowers, and chocolates. But more important than any material gift, the best thing for spouses (besides the word and prayer) is simply time. Time to talk, time to listen, time to read, time to reflect.

With that in mind, here are five marriage books worth reading (together or separately) and five questions husbands and wives can ask themselves and share with each other.

Five Books

Timothy Keller with Kathy Keller, The Meaning of Marriage: Facing the Complexities of Commitment with the Wisdom of God (Dutton, 2011). Full of wisdom. Sneakily, a book about self-denial as much as it is about marriage. Keller is especially good at helping you see that the person you married is not the person you’ll be married to 20 years later.

Paul David Tripp, What Did You Expect: Redeeming the Realities of Marriage (Crossway, 2010). As you would expect from Paul Tripp, this book has plenty of stories and plenty of direct hits right between the eyes. The title tells you what kind of help Tripp means to give.

Jim Newheiser, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: Critical Questions and Answers (P&R, 2017). Don’t let the prosaic title fool you. This book is an excellent theological and counseling primer on marriage, with 40 questions covering the waterfront: from conflict resolution, to sexual problems, to the portrait of a successful marriage.

Walter Wangerin Jr., As for Me and My House: Crafting Your Marriage to Last (Thomas Nelson, 1990). One of the best books I read before I got married. Wangerin is a gifted writer and master storyteller.

Elisabeth D. Dodds, Marriage to a Difficult Man: The Uncommon Union of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards (Audubon, 2004). History is one of our most neglected teachers. Read this book for a compelling picture of an unknown side of the great theologian. A detailed, realistic, and beautiful picture of the Edwards family.

Five Questions

You may choose to rework these questions and present them to your spouse to answer. But I usually find it easier to answer the questions for myself and then share with my wife (and I know my wife would rather talk about her experience than have me put her on the spot to talk about me).

What is one thing your spouse does that always makes you smile or laugh?

What is a good memory you have of the two of you from the last year? Feel free to share your answer for the last 5 or 10 or 50 years too.

What is one thing you’d like to improve on, or one area of your character you’d like to see grow, in order to love your spouse better?

Of the nine fruits of the Spirit, which one did you first notice in your spouse when you fell in love? Which one have you appreciated most in the past year?

Even if it meant saving for 10 years, or finding a team of babysitters, what is one thing you’d love to be able to do (or a place you’d like to go, or something you’d like to experience) with your spouse in the future?

There you go. You have plenty to read and plenty to talk about. Now you just need to find 30 minutes to get away and be alone together. Better yet, find a few hours.

P. S. Not married? You may want to check out Sex, Dating, and Relationships (Crossway, 2012) by Gerald Hiestand and Jay Thomas. Are you married with single friends? You may want to read this post on what not to say to single women in your church (or to men for that matter).

February 11, 2018

Monday Morning Humor

An oldie, but a goodie: that dreaded silver medal, strangle a guy, the involuntary luge.

February 5, 2018

On Writing Books and Getting Published

It’s one of the questions I get asked most frequently: “I want to write a book and get published. What advice do you have for me?”

Sometimes the questioner is just looking for an in, as in, “Can you send this to your friends and get me a deal?” But usually the questioner is genuinely looking for any insights they can glean from others. I understand the question. I asked it of my published friends before I wrote my first book. It was always a dream of mine to write and–maybe, just maybe, someday before I die–get published by a real publisher. I never imagined the open doors the Lord would provide.

Although I didn’t get published because an insider greased the wheels, my friends certainly helped me along the way with good counsel and realistic advice. Let me try to do the same for the good folks out there with good book ideas rattling around in their heads or on their computers.

Writing

We’ll start with writing and then move to publishing. There is no one right way to get a book written. I’ve known pastors who write from 10pm to midnight, and others who get up at 4am and write for several hours in the morning. Some authors crank out books in months or weeks (or days!). Others labor for years, struggling over every word.

This is what works for me: I don’t do well writing books in fits and starts, or a couple hours at a time. I did that with the homosexuality book and found it the least enjoyable of the books I’ve written (the difficult subject matter and the tedious review process were also partly to blame). I much prefer to write a book from start to finish during an extended study leave. Most of my books have been written in this way.

Whether it was the book on holiness or busyness or the mission of the church, I started 6-12 months out by reading everything I could on the subject. By “everything” I don’t mean exhaustive academic research. I mean everything I can easily get my hands on. That usually amounts to 15-20 books over the course of a year and a smattering of articles and blog posts.

During the reading process I’m constantly playing with the shape of the manuscript in my mind. I underline, jot down notes, and begin sketching out chapter titles. After 6-12 months of reading (which I squeeze into whatever time I can find–on a plane, before bed, waiting in line), I usually have a good working outline of my chapters and some subheadings within those chapters.

When I come to my four-week study leave, I’ve done most of the research and a lot of the heavy thinking already. That means I’m ready to write on day one. I’m typically a pretty fast writer once I know where I’m going and what I want to say. I may write 1,000-2,000 words a day, which amounts to a short book (25,000) or a medium-sized book (40,000+ words) in a month. That may sound like a lot, but I’m not doing academic research, I’m not cramming in tons of footnotes, and I already know (fairly well) where I’m going when I first sit down at the keyboard.

How can you improve as a writer? That’s a tough question. There are good books out there that can help with the craft. But without a doubt the best advice is to simply write and read a lot. You need both. You’ll never learn new words, discover new arguments, and adopt new forms if you don’t read. And you won’t get better at writing without lots of writing.

And not just any writing, deliberate writing. You already write texts and emails and Facebook updates and tweets and Christmas cards, so why not do these things excellently? Force yourself to use correct punctuation. Give yourself a word limit. Be punchy and succinct.

The other piece of advice is to read your own writing out loud. As often as I tell students to do this, they must still skip over this step, because they make so many mistakes they would easily catch if they had to verbally speak their own sentences.

Publishing

Okay, you’ve got a great book already written. You just need a publisher. Now what?

Find an honest friend. I’ve met many people over the years who want me to see their amazing book idea. They try to tell me, with appropriate humility, how all their friends have raved about the material and how it obviously needs to be published. More often than not, their friends are poor judges of literary merit. Get a critical, honest friend you can trust. Don’t ask me what I think! Ask him or her whether your writing is good or not. Be prepared to have your feelings hurt.

Don’t expect wonders from your author or publisher friends. You may have a good buddy who works with a publisher or who has written a book himself. Of course, you should feel free to ask him questions and seek his advice. But don’t look for favors. I’m very wary of passing along manuscripts to people I know in the industry. It’s not because I don’t want to help, but because I want to help everyone. That means I don’t want to flood my friends with unsolicited manuscripts that they now feel obligated to read. That may sound hoity-toity, but it’s what my friends told me when I started out too. I respected them for their integrity and honesty with me.

Publishers don’t stay in business unless they sell books. To be sure, this is not an excuse for publishers to care about nothing besides the bottom line. And yet, they do have to care about the bottom line, which is why they generally want to publish books that actually sell. It’s hard to get into publishing because most publishers work with recognized authors (whom they trust to write good stuff) and/or with recognized agents (whom they trust to pass along good stuff). It’s not a perfect system. Good stuff gets left out, and bad stuff gets put out. But all those I’ve worked with at Crossway and Moody have been godly people trying to do the best they can to publish solid material that can still recoup their investment.

Go ahead and submit a couple chapters. Most publishers don’t take unsolicited manuscripts, at least not officially. But publishers still have someone taking a look at the manuscripts that come in. When Ted Kluck and I were shopping around the emergent book, we got lots of no’s. It only took one person at Moody to like what we sent in and give us a chance.

Be smart about your submission. Shorter is better. Don’t brag about yourself. Don’t oversell your book as the most important thing since the 95 Theses. Don’t send in the whole manuscript. Do, however, include a couple endorsements from trusted authors, scholars, or leaders. I know it helped our emergent book see the light of day that we had already lined up David Wells to do the Foreword. There’s other homework you can do too. Specify a target audience in your proposal (claiming that your book will bless everyone doesn’t count), and show that you know what kind of audience the publisher tries to reach.

Getting a book published is like a horse race. This is the analogy my published friend told me years ago when I was still dreaming of writing a book someday. His analogy has always stuck with me. In publishing, the author is like the jockey, the topic is like the horse, and the cultural moment is like the race track. Publishers generally want at least two of the three to be in a strong position for success. Take the emergent book, for example. The jockey (me) was nothing. Ted had written some books, which helped, but no one was interested in what Kevin DeYoung had to say about anything. The topic, however, was relevant, and we were young at the time. Likewise, the cultural moment was just right; the emergent movement was at its zenith. We had two of the three factors in our favor, so Moody took a chance on some unknown jockeys.

You need something unique to say, or some unique way to say it. If you’re Tim Keller, thousands of people are already eager to hear what you have to say–about almost anything. For the rest of us, we need to work hard to come up with something unique. Actually, that last sentence isn’t fair to Keller, because what he does so well is take familiar material (e.g., prayer, marriage, work, justice, apologetics) and present it in a way that feels fresh and original. People are eager to hear from Keller because they know he will provoke them to think about something in a new way. Sorry to say, unless you are a world class scholar or extremely gifted communicator, most people don’t care about the devotional you’ve written, your latest sermon transcripts, or the Bible studies you’ve done on Ezekiel. Maybe people should care, but they don’t. You need a hook that makes your work worth reading. When I pitched another “find the will of God” book to Moody, they were skeptical, but when I came up with the angle “just do something,” it became interesting. Along these lines, you should mention the “competition” in your proposal. Make the case that your book on parenting is different (a new approach, more research, more readable, personal stories, etc.) than the three dozen other books on parenting.

Publishing is not a divine assessment of worth. We all know there are plenty of crummy Christian books. In fact, the bestselling books are often the worst. Conversely, there are faithful resources out there, full of truth, that never see the light of day. Publishing does not always reward great writing and profound truth. Some publishers do the best they can. Others don’t. Either way, the system will never be foolproof. Some things are out of your control. So go easy on the self-promotion. Don’t retweet commendations. Don’t do humblebrags. Don’t puff your own stuff. If you do get published, let people know about the book, point people to more information, and then move on.

Self-publishing is not a failure. My first book, Freedom and Boundaries, was self-published. This wasn’t my first choice (and now the book is out of print because the publisher went belly up), but it wasn’t a bad second choice. The book got an ISBN number, it went on Amazon, I gave it to people at my church, I had something to recommend to my friends and family. No shame in any of that. Similarly, consider writing articles before you dream of writing a book. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither are the good books about Rome.

If you like to write, keep writing. Whether you get published or not, if you have something true and useful to say, it will be a blessing to someone. Start a blog, get some traction, see what happens. Most books sell in the thousands, if not the hundreds. Publishers stay in business behind a few mega-hits. So even if you don’t get published, if you work hard and have an important, well-written message to convey, you may be able to get your stuff out to almost as many people. If your real passion is to get published, you’ll likely be disappointed. Check your motives. Write because you love to write.

There you go. I hope I’ve given the right mix of optimism, pessimism, and realism. Writing is good, and you can get better. Publishing is hard, and it may not happen. Don’t stop reading. Hone your craft. Learn, grow, be self-aware. And as Calvinists like to say, good luck!

January 31, 2018

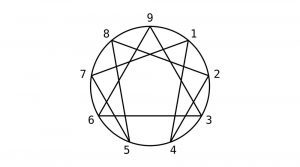

Enneagram: The Road Back to You, Or to Somewhere Else?

If you haven’t heard of the Enneagram yet, it won’t be long before you do.

After being used for several decades in Catholic retreats and seminars, the nine-type personality tool has seen an explosion of popularity in evangelical circles. Since 2016, evangelical publishers have released at least three-full length books on the Enneagram: The Road Back to You: An Enneagram Journey to Self-Discovery (IVP 2016), The Sacred Enneagram: Finding Your Unique Path to Spiritual Growth (Zondervan 2017), and Mirror for the Soul: A Christian Guide to the Enneagram (IVP 2017). A new book—The Path Between Us: An Enneagram Journey to Healthy Relationships (IVP)—is set to release in April.

Beyond books, the Enneagram (pronounced any-a-gram) continues to receive a warm reception on a number of blogs and evangelical media outlets with articles like: “What All Christians Need to Know About the Enneagram” and “The Never Ending Quest to Know Ourselves.” In particular, Christianity Today has been a frequent advocate of the Enneagram, touting what the Enneagram has to offer Christians, how evangelicals can use it, and, just recently, how it can be a tool for pastors. On a personal note, I have good friends who swear by the Enneagram as the means by which God showed them their blindspots and helped them overcome weaknesses in their personality.

So what should we make of this new (or ancient?) personality wheel with a strange name?

Journey of Discovery

I want to get at the question in a simple, straightforward—and admittedly limited—way. I’m going to look at The Road Back to You by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile. I’ve chosen this book for several reasons: it was the first one (so far as I know) to come out with an evangelical publisher, it has been successful enough to spawn a soon-to-be-released sequel, and its authors are popular experts on all things Enneagram.

I understand that some fans of the Enneagram will say, “But that’s now what I believe!” Or, “That’s now how I use it!” I get that. It’s a tool that can be adopted and adapted to a variety of theologies and contexts. But you have to start somewhere, and The Road Back to You seems as good a place as any to dive in and interact with this increasingly popular tool of self-discovery. Hereafter in this post, my analysis with the Enneagram will be through reviewing this single book.

So What Is It?

Ok, enough preface. What are we actually talking about?

The Enneagram teaches that there are nine different personality styles in the world, one of which we naturally gravitate toward and adopt in childhood to cope and feel safe. Each type or number has a distinct way of seeing the world and an underlying motivation that powerfully influences how that type thinks, feels and behaves. (24)

While the ancient roots of the Enneagram are sketchy—maybe it started with a monk, maybe with with Sufism, maybe with occult practices—most everyone agrees that the modern Enneagram entered America by way of the psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, a student of a Chilean named Oscar Ichazo who rediscovered the Enneagram in the early 1970s. From Naranjo, the Enneagram entered the Catholic world through Father Robert Ochs, and then later made another splash when the Franciscan Friar Richard Rohr began writing and speaking on it (10-14).

At first glance, the Enneagram may look like just another personality test, along the lines of discovering your Myers-Briggs type, knowing the color of your parachute, finding your strengths, or realizing you’re a golden retriever instead of a beaver. But Cron and Stabile are adamant that the Enneagram is much more than a psychological profile. “The true purpose of the Enneagram is to reveal to you your shadow side and offer spiritual counsel on how to open it to the transformative light of grace” (31). Growing up, we learn to cope with the emotional wounds we receive in childhood. In order to protect us from pain, we “place a mask called personality over parts of our authentic self” (22).

The Enneagram is not the end-all and be-all of Christian spirituality, Cron and Stabile acknowledge, but it is an incredibly useful tool God can use to help restore us to our authentic selves (20, 23). “Buried in the deepest precincts of being,” Cron writes, “I sense there’s a truer, more luminous expression of myself, and that as long as I remain estranged from it I will never feel fully alive or whole” (23). At its root, the Enneagram is a healing message of self-knowledge and self-awareness (34). We all put on masks. We all struggle to feel like we are okay in the world and okay to be who we are. Enter the Enneagram as a tool for letting go of the stranger we’ve become (24). “The purpose of the Enneagram is to show us how we can release the paralyzing arthritic grip we’ve kept on old, self-defeating ways of living so we can open ourselves to experiencing more interior freedom and become our best selves” (36).

Each of us has one of nine, fixed personality types (ennea being the Greek word for “nine”). Cron and Stabile label the nine types: (1) the perfectionist, (2) the helper, (3) the performer, (4) the romantic, (5) the investigator, (6) the loyalist, (7) the enthusiast, (8) the challenger, and (9) the peacemaker. Each personality type, in turn, belongs to a particular triad (related to your head, heart, or gut), has wing numbers (leaning into other types), stress numbers (the bad qualities you pick up when you’re unhealthy), and security numbers (the good qualities you pick up when you’re healthy). The bulk of the book moves through each type (not in order), explaining what these people are like, what famous people are like them, what they need to confront in themselves, and how each of us needs the grace of God to learn to be okay with our true self.

Commendation

The book is written in Cron’s voice with Stabile’s Enneagram expertise in the background. Cron is a good writer—clear, funny, informative, and entertaining.

I also appreciate how the book takes seriously our need to change. This is NOT a book that says you are fine just the way you are. Your personality type may be fine, and your true self may be luminous, but the way we all act is tainted with unhealthy habits. Cron and Stabile want us to stop hurting people, including ourselves. That’s commendable.

More to the point, I don’t doubt that many people can learn useful things about themselves and others from the Enneagram. I always find that books like this have a few good commonsense nuggets of truth. I’ve done Myers-Briggs, DISC, spiritual gifts inventories, spiritual temperament books, strength finders, and a smattering of other self-discovery books and tests. It can be helpful to realize that you are driven to succeed, or that your co-worker hates conflict, or that your spouse is an adventurous romantic. When put in their proper place, there’s something to learn from the find-your-personality literature.

Critical Interaction

And yet, on the whole, The Road Back to You is bound to be more harmful than helpful. Let me mention three criticisms, finishing with the most serious.

First, the Enneagram, as presented in this book, is far less revolutionary than most proponents would have you believe. I have to admit I found the whole thing tedious and formulaic. If you offer a one-sentence description of each number to a thoughtful, mature adult, I bet he could pretty well describe each type without any knowledge of the Enneagram. There’s only so many ways to skin a cat. We’re all sanguine, choleric, melancholy, or phlegmatic. Or we’re lions, golden retrievers, beavers, and otters. Or we’re ESTJs and INFPs and everything in between. Once you know that Eights (the challenger) are commanding, confrontational, and afraid of being vulnerable, the analysis writes itself.

The book started running together in my mind as I learned that Nines were wounded as children and need to hear the message that God loves them . . . and Twos were also wounded as children and need to hear the message that God loves them. Ones need to hear, “You’re imperfect, and you’re wired for struggle, but you are worthy of love and belonging” (108), while Threes need to hear, “You are loved just for who you are” (146). As a cure of souls, the Enneagram, once you get past all the fancy triads and wings, is one size fits all: stop trying to measure up, find your true self, and accept that God loves you and will take care of you.

Second, the Enneagram has an air or scientific precision without any real basis for authority. Throughout the book, we read about “so-and-so who is an Eight” or “my friend who is a Two,” as if we were mentioning someone’s height or hair color. One of the author’s daughters is even confidently labeled as a 9w8 (Nine with an Eight wing). But what do these designations really amount to? Cron writes that every Eight he knows oozes confidence (44). Of course they do, because that’s what we’ve defined Eights to be. If they were timid and unsure of themselves, we’d give them another number.

It wouldn’t be so bad to give ourselves observational labels, except that Cron and Stabile insist that personality type never changes (37). This is who we are, and we must discover our own number. But what if the whole thing is a crap-shoot? Is it really the case they every Eight (the challenger) picked up the wounding message as a child that the world is a hostile place where only the strong survive (48)? And how do we really know that Barack Obama, Bill Murray, and Renee Zellweger are Nines (67)? Or that Jerry Seinfeld, Nelson Mandela, and Hillary Clinton are Ones (93)? Or that Sixes like Ellen Degeneres and Jon Stewart have a deep-seated need to feel secure (191-92)? Again, it’s one thing to make general comments about how certain types of people tend to respond in certain ways. It’s quite another to develop an elaborate system that assigns a lifelong number to people and then confidently assigns motivations and unpacks their childhood accordingly.

Third, and most importantly, the Enneagram presents an approach to spirituality that is alien to, and often at odds with, the language and contours of Scripture. Although Cron and Stabile argue that the Enneagram does not smuggle in the therapeutic under the guise of the theological (24), the book is awash in therapeutic language. Every chapters talks about some combination of forgiving myself, finding my true self, becoming spiritually evolved, being healed from wounded messages, dealing with codependent behaviors, and pursuing personal wholeness. This is not the language of the Bible. We hear nothing about fear of man, the love of the praise of man, covenantal promises, covenantal threats, repentance, atonement, heaven or hell. When faith is mentioned it’s described as believing in something or someone bigger than you (203).

The spirituality of the Enneagram in The Road Back to You bears little resemblance to biblical spirituality. In the book we meet a man named David who is described as having a “meet Jesus” crisis that “brought him face-to-face with himself.” You would have thought that a “meet Jesus” moment would bring you face-to-face with Jesus. But in this case David learned to put effort into becoming his true self, so that he says, “Today I think far less about working and winning and more about David-ing” (136). Not surprisingly, then, the last page of the book includes this line from Thomas Merton: “For me to be a saint means to be myself” (230).

To be sure, The Road Back to You has a fall, but it is not mankind’s sinful rebellion against God. It’s that we’ve “lost connection” with our God-given identity (230). In a critical section at the beginning of the book, the authors describe their understanding of sin: “Sin as a theological term has been weaponized and used against so many people that it’s hard to address the subject without knowing you’re possibly hurting someone who has ‘stood on the wrong end of the preacher’s barrel,’ so to speak.” To be sure, we must face “our darkness,” but then Cron and Stabile give this definition of sin (from Rohr): “Sins are fixations that prevent the energy of life, God’s love, from flowing freely. [They are] self-erected blockades that cut us off from God and hence from our own authentic potential” (30). To quote their definition is to refute it. There is nothing here about sin as lawlessness, sin as spiritual adultery, sin as cosmic betrayal against a just and holy God.

Yes, the great Christian theologians have talked about the importance of knowing oneself. Calvin, for example, is cited as one who argued for the necessity of self-discovery (15). True, Calvin argues that we must know ourselves to know God (15), but what we must know is our “shaming nakedness” which exposes “a teeming horde of infirmities.” Knowledge of self is indispensable because from “the feeling of our own ignorance, vanity, poverty, infirmity” we can recognize “that the true light of wisdom, sound virtue, full abundance of every good, and purity of righteousness rest in the Lord alone” (Inst. I.1.i).

The Road Back to You has no doctrine of conversion, because the human condition described has no need of regeneration. “It may be hard to believe,” Cron and Stabile write, “but God didn’t ship [Fours] here with a vital part absent from their essential makeup. Fours arrived on life’s doorstep with the same equipment everyone else did. The kingdom is inside them too. Everything they need is here.” (165) This is not evangelical spirituality. It’s no wonder the book does not interact with Scripture (except for referencing the story of Mary and Martha) and quotes mainly from Catholic contemplatives like Thomas Merton, Richard Rohr, and Ronald Rolheiser, while also referencing “spiritual leaders” like the Dalai Lama, Lao-Tzu, and Thich Nhat Hahn. You don’t have to be a Christian to benefit from the Enneagram journey in this book, because there is nothing about the journey that is discernibly Christian.

Conclusion

The book begins and ends with a prayer—a prayer of blessing that perfectly captures what The Road Back to You is about:

May you recognize in your life the presence, power, and light of your soul. May you realize that you are never alone, that your soul in its brightness and belonging connects you intimately with the rhythm of the universe. May you have respect for your individuality and difference. May you realize that the shape of your soul is unique, that you have a special destiny here, that behind the facade of your life there is something beautiful and eternal happening. May you learn to see yourself with the same delight, pride, and expectation with which God sees you in every moment. (18-19, 230)

I’m sure that some Christians will be quick to respond, “Sounds like a goofy book, but that’s not how I use the Enneagram.” I’m thankful for that. But then I’d encourage these brothers and sisters to dial back the Enneagram enthusiasm, like way back. If you want to scrap most of the Enneagram history, therapeutic baggage, and Catholic mysticism, I suppose you could still have a personality tool that might open your eyes to a thing to two. But then I’d glean a few insights quietly and distance myself from the seminars, the experts, the books, the articles, and the nomenclature of the Enneagram. If the Enneagram were another version of What Color Is Your Parachute? or Strengths Finder, that would be fine. But it has been, from its inception (whenever that was), infused with spiritual significance. And therein lies the danger.

January 22, 2018

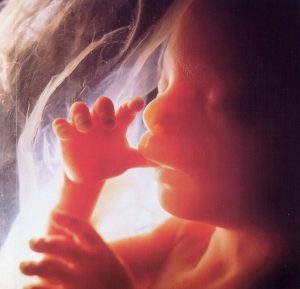

Life is Precious

Life is precious.

Every human life. After all, a person’s a person, no matter how small.

At 18 days, the baby’s heart begins to beat.

At 21 days, it pumps its own blood with its own blood type through its own circulatory system.

At 28 days, its eyes, ears, and respiratory system begin to form.

At 42 days, brain waves can be recorded and reflexes are present.

At 7 weeks, you might see an image of your baby sucking its thumb.

At 8 weeks, all body systems are present.

At 9 weeks, before most women show (or maybe even know) that they are pregnant, the baby can squint, swallow, move its tongue, and make a fist.

At 11 weeks, the baby has fingernails and makes spontaneous breathing movements.

At 15 weeks, the baby has an adult’s taste buds.

At 16 weeks, the genital organs are clearly differentiated, and the baby can grasp with its hands, swim, kick, turn, and do somersaults not even felt yet by the mother.

At 17 weeks, the baby can dream.

At 18 weeks, the vocal chords work, and the baby can cry.

At 20 weeks (the time of your ultrasound), the baby has hair on its head, weighs a pound, and is a foot long. The child can recognize its mother’s voice.

At 24 weeks, well more than half of all babies in this country survive premature birth, and the number goes up exponentially every week thereafter.

And these children do not have a right to life?

Are bigger people more deserving of protection than smaller people? Does your 3-year-old have more rights than 3-month-old because she can talk? Does a teenager have more rights than a 4-year-old because he can drive? Do your rights as a human person change when you’re in your car, in your home, in a suit, in your bathrobe, or underwater? Does your environment change what sort of rights you have as a person? Why should those inches down the birth canal change the rights that child has as a human person? “Well, the baby is completely dependent upon the mother.” Does the person who relies on daily insulin injections to live have less of a right to do so? What about the person who has to go multiple times a week for dialysis, or they will die? Do they have less of a right to live? What if you have to take pills every morning to keep your cholesterol down so that you don’t die a premature death? Do you, because you are dependent upon those, have less of a right to live?

Every human life is precious. Unborn life is precious. Children with special needs are precious. Aging parents are precious—even when they don’t remember because they’re suffering dementia, they’re still made in the image of God. Children or parents who are non-verbal, those in a wheelchair, and those who are completely dependent upon you or doctors are precious. All of life matters to God. If we have our eyes open, we can see this in even the most surprising places in the Bible, like in the lex talionis of the Mosaic law. You see it in imago Dei. You see it in the incarnation where God entered the world as a helpless babe.

Defend, honor, and give thanks for life—yours, your children’s, and your parents’. May we all pray, work, and labor—no matter what political party we’re a part of or who we voted for—so that every human life is protected, prized, and considered precious.

January 19, 2018

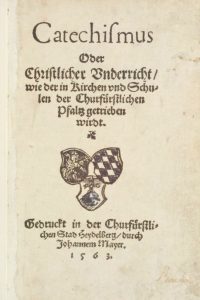

Happy Birthday Heidelberg

Today is the 455th birthday of the Heidelberg Catechism.

I grew up with the Heidelberg. I don’t recall having to memorize it cold like some organic chemistry nightmare. It wasn’t always front and center in my life, but it was always there.

I’ll forever be grateful to my childhood pastor for making me read the Heidelberg Catechism and meet in his big office with him to talk about it before I made profession of faith in the fourth grade. I was nervous to meet with him, even more nervous to meet before all the elders. But both meetings were pleasant. And besides, I was forced to read through all 129 questions and answers at age 9. That was a blessing I didn’t realize at the time. Ever since then I’ve had a copy of the catechism and have grown to understand it and cherish it more and more over the years.

An Old Story

In 1562, Elector Frederick III of the Palatinate, a princely state of the Holy Roman Empire (think Germany), ordered the preparation of a new catechism for his territory. A new catechism would serve three purposes: (1) as a tool for teaching children, (2) as a guide for preachers, and (3) as a form for confessional unity among the Protestant factions in the Palatinate. Frederick wanted a unifying catechism that avoided theological labels and was plainly rooted in the texts of Scripture. To that end, he commissioned a team of theological professors and ministers (along with Frederick himself) to draft a new catechism. Although the catechism was truly a team effort (including Caspar Olevianus who used to be considered a co-author of the catechism, but now is seen as simply one valuable member of the committee), there is little doubt the chief author was Zacharias Ursinus.

Ursinus, a professor at the university in Heidelberg, was born on July 18, 1534, in what is today Poland but at that time was part of Austria. Ursinus was the chief architect of the Heidelberg Catechism, basing many of the questions and answers on his own Shorter Catechism, and to a lesser extent, his Larger Catechism. The Heidelberg Catechism reflects Ursinus’s theological convictions (firmly Protestant with Calvinist influence) and his warm, irenic spirit.

This new catechism was first published in Heidelberg (the leading city of the Palatinate) on January 19, 1563, going through several revisions that same year. The Catechism was quickly translated into Latin and Dutch, and soon after into French and English. Besides the Bible, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and Thomas a Kempis’s Imitation of Christ, the Heidelberg Catechsim is the most widely circulated book in the world. Since its publication in 1563, the Heidelberg Catechism has been used in scores of languages and widely praised as the most devotional, most loved catechism of the Reformation.

An Old Friend

Not everyone is as keen on catechism as I am. For some, catechisms are too linear, too systematic, too propositional. For others, the catechism gets a bad rap because, fairly or unfairly, the only stories that we hear about catechetical instruction are the stories of old Domine Vander SoAndSo who threatened to smite us hip and thigh if we couldn’t remember what God required of us in the eighth commandment.

More often, catechisms simply never get tried because they are said to be about theology and theology is said to be boring and words like “Heidelberg” and “Westminster” are even more boring. (Incidentally, I have never been a fan of snazzy Sunday school curriculum that tries to pretend that a catechism is something other than questions and answers about the Bible. You can call it “Journeys with God from the Palatinate” or “Heidelberg Truth Rockets” but it’s still a catechism and our kids know it.)

But even with all this bad press, I am firm believer in catechisms, especially the best ones like Westminster or Heidelberg. I’ll never forget sitting in my Christian Education class at my evangelical, non-Dutch, non-denominational seminary. One of our assigned texts was the Heidelberg Catechism—this little book that growing up was usually good for rolling the eyes of students into the backs of their little heads. But my fellow students at seminary marveled at this piece of work. “Where has this been all their lives?” “This will be perfect for Sunday school!” “I’m going to use this for new member’s classes!” Most of the Dutch Reformed kids I knew were ready to see the Heidelberg Catechism go the way of the dodo bird. But at seminary, my classmates were seeing something many of my peers had missed: the Heidelberg Catechism is really, really good.

Happy birthday, old friend. May you make many new friends in the years ahead.

Want to know more about Heidelberg? Check out The Good News We Almost Forgot: Rediscovering the Gospel in a 16th Century Catechism.

January 15, 2018

One Simple Thought On MLK Day

Just one thought, and it is this: every human being—regardless of color, nationality, economic status, or intellect—has been created in the image of God and should be treated with dignity and respect.

Yes, we all know that. Or at least we should know that as Christians. It’s biblical anthropology 101.

And yet, when push comes to shove—when people look different and act differently, when people come from parts of the country or places in the world that seem dirty or dangerous—it’s easy to forget.

We can all roll our eyes or stomp our feet at the President’s apparent remarks about [expletive] countries. Most of us don’t talk that way, and certainly wouldn’t dare to do so in a (semi)-public setting. But we’d be fooling ourselves if we imagine we never think that way.

“Careful, they’re from the ghetto.”

“Ugh, she’s from the South.”

“Why are people like that so backward?”

“I can’t believe he’s so smart; he’s from the country you know.”

“City people are so full of themselves.”

“That’s Europeans for you.”

“Probably Americans.”

“It’s Africa, what do you expect?”

We are a fiercely tribal people, and social media only serve to make us more social with our kind and less social with everyone else. It’s Red State, intolerant, flag-waving, Muslim-hating, science-denying white people from bigoted churches in fly-over country against Blue State, cosmopolitan, anti-American, religion-hating, race-baiting hypocrites from Hollywood and academia. Take your pick. And pick your poison.

I’m not calling for a naïve “let’s all get along” solution that solves nothing, let alone for a squishy moral equivalence that suggests no one has any better ideas or better ideals than anyone else. But the Bible does call us to love our neighbors as ourselves. And it would have us consider that we are more the same than we are different: same parents from the Garden, same sin nature from Adam, same broken hearts, same busted image, same need for the same Savior.

Different skin, same kind of soul. That’s a truth the probably hasn’t sunk in as deeply as we think it has. The imago dei is not going to fix everything that ails us, but a proper understanding of who we are is necessary if we are going to really see that we deserve the same dignity and the same respect no matter who we, what we look like, or where we come from.

January 4, 2018

20 New Year’s Resolutions You Can Make (and Keep) Right Now

Making New Year’s resolutions is easy. Keeping them is hard. Some Christians think the annual habit of making new goals is legalistic, ill-conceived, and doomed to failure. I’m not so negative. I think the new year provides a good opportunity to evaluate current practices and consider how the Spirit might enable us to set better priorities in the future.

But this post isn’t about arduous resolutions. Well, not exactly. It’s about something simpler. It’s about your calendar and about making decisions now that will serve you later in the year.

As the saying goes, the hardest step is often the first one. So if you can get important dates down on your calendar, you are already well on your way to getting that important thing done.

So here are 20 things you may want to consider putting on your 2018 calendar over the next week. No one will do all of these, or even most of them, but as I look at my life, I realize that adding just a few of these dates would be a big step in the right direction.

Schedule a date night with your husband or wife for sometime in the next six weeks. Take Valentine’s Day if you have to.

If you are a pastor, or have flexibility in your schedule, put two prayer days on the calendar for 2018.

Sign up for a 5k race.

Plan a special one-on-one outing with one or more of your kids.

Put a date on the calendar when you and your friend will recite the Bible verses you’re memorizing.

Invite over the new family from church and get it down on your calendar.

Set up a time to talk on the phone with that old friend you’ve about lost touch with.

Make a written commitment to give an extra financial gift in 2018 to your church, your school, your missionaries, or some other gospel-centered cause.

Plan for a week-long digital fast and get the dates on your calendar.

Buy tickets to a ball game, a concert, or a special show. If you can, buy extra tickets so you can invite someone who needs a night out.

Call up a hurting person and ask for the best time to bring over a meal or take them out to dinner. Don’t take no for an answer.

Pencil Sunday school or the evening service into your Sunday schedule. Give it a good try for a month.

Get your vacation plans firmed up. Make the arrangements now, then start saving. And remember, it’s usually better to spend money on experiences and memories as opposed to stuff.

Clear off a work day sometime in the next year. Surprise your family by staying home.

Circle Pie Day on your calendar (3.14) and make plans to bring pie to an assisted-living facility or to your neighbor’s house.

That’s probably enough ideas to get you started. “But you said you had 20 things!” you might interject. True, but the last five are for calendar clearing, not for calendar filling.

If you are in more than two Bible studies/small groups, and neither is evangelistic in nature, consider removing one from your schedule if it frees you up to be more present at home and less stressed for your family.

If your kids are doing more than one sport or activity a season, try cutting it back to a single thing each season, especially if the events are causing you to miss corporate worship.

Turn one of your planned getaways into a stay-cation.

Put a Sabbath week (or even a three-day stretch) in your calendar twice a year. Keep the dates rigidly free of activities. Use the time to catch up on chores, catch up on your Bible reading, or just catch your breath.

Get more sleep, and don’t feel guilty about it. Make those seven or eight hours as immovable as possible and adjust the rest of life accordingly.

Nothing revolutionary. And nothing mandatory (though evening worship comes close). But hopefully something helpful for everyone to consider.