Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 18

December 26, 2017

Top Ten Blog Posts of 2017

I like lists, and year-end lists in particular are always fun. So here’s a list of my top ten most viewed blog posts from the past year. While I wasn’t surprised by what came out on top, I was pleased to see that many of the popular posts were about books and theology (which is what I prefer to write on), as opposed to pop culture commentary (which has its place).

I Don’t Understand Christians Watching Game of Thrones. I don’t expect those who are strangers to the light to be bothered by the darkness. But for conservative Christians who care about marriage and immorality and decency in so many other areas, it is baffling that Game of Thrones gets a free pass.

One More Time on Game of Thrones. Only in a hyper-sexual, pornographic-saturated culture like ours could we think that graphic sex scenes are no big deal, or somehow offset by a brilliant screenplay.

Best Books of 2017. This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year.

Immutability and Reformed Theology. If God is whatever God has, as the traditional doctrine states—that is, if every attribute of God is identical with his essence—then it does not make sense to say that God can undergo a change of any kind (atemporal or temporal) that does not also imply a change in essence.

Theological Primer: The 144,000. The 144,000 are not an ethnic Jewish remnant, and certainly not an Anointed Class of saints who became Jehovah’s Witnesses before 1935. The 144,000 “sealed from every tribe of the sons of Israel” (Rev. 7:4) represent the entire community of the redeemed.

Why I’m Not Allowing Laptops in My Seminary Class. I want people caught up in listening, not frantic about getting the perfect notes that lead to the perfect grade. And if worse comes to worse, and they end up moderately bored for an hour instead of infinitely distracted, that’s not bad either.

Seven Characteristics of Liberal Theology. Liberalism is both a tradition—coming out of the late-18th century Protestant attempt to reconfigure traditional Christian teaching in the light of modern knowledge and values—and a diverse, but recognizable approach to theology.

Protestant and Catholic: What’s the Difference? As we mark the 500th anniversary of Reformation, it’s important to be conversant with some of the main issues that legitimately divide Protestants and Catholics, lest we think all the theological hills have been laid low and all the dogmatic valleys made into a plain.

All That Is In God. However much we may want to champion God’s relatability and intimate compassion, deviating from classical theism is not the way to do it.

The Two Things We Must Say About the Transgender Debate. While we do not have patience for secular agendas, we must have patience for struggling people. We may be quick with rebuttals in the public square, but we must be quick with a listening ear in the neighbor’s kitchen.

December 20, 2017

Book Briefs

There are always more books than time, but here are some of the books I’ve enjoyed reading in the past few months.

Wayne R. Spear, Covenanted Uniformity in Religion: The Influence of the Scottish Commissioners on the Ecclesiology of the Westminster Assembly (RHB, 2013). The book is what it says it is: an examination of how John Maitland, Alexander Henderson, George Gillespie, Robert Baillie, Samuel Rutherford, and Archibald Johnston shaped the Assembly’s doctrine of the church. Spear does a good job demonstrating which issues were controversial and where compromises had to be reached. He also shows how the Scottish commissioners often brought to London a more robust (and more opinionated) view of ecclesiology than their English counterparts.

Colin Marshall and Tony Payne, The Vine Project: Shaping Your Ministry Culture Around Disciple-Making (Matthias Media, 2016). The practical, how-to follow up to The Trellis and the Vine. At 350 pages, I wish the book were a little shorter, but the process Marshall and Payne lay out is extremely valuable. I’ve just started using the book with a vision committee in our church.

Jason L. Riley, False Black Power? (Templeton Press, 2017). Riley, a Black conservative, argues that the current Civil Rights Movement has done little to help Blacks get ahead in life. Riley insists that true power for African Americans comes not by looking to politicians, but by looking to their own past. The book finishes with (partially) dissenting opinions from John McWhorter and Glenn Loury.

Andreas J. Kostenberger and Scott R. Swain, Father, Son and Spirit: The Trinity and John’s Gospel (IVP, 2008). This book was helpful for my Systematic Theology course and continues to be helpful as I preach through the Gospel of John. I’ve been edified by every volume I’ve read in the NSBT series, and this is no exception. The chapters are well organized and can be used as a stand alone essay if you don’t have time for the whole book.

D.A. Carson, Praying With Paul: A Call to Spiritual Reformation, Second Edition (Baker Academic, 2014). Somehow I had never read this volume from the Carson canon. I’m very glad I did. Simply put: It’s one of Carson’s best books and one of the best books on prayer period. A great mix of conviction, inspiration, and exegetical insight.

Jonathan Beverly, Your Best Stride: How to Optimize Your Natural Running Form to Run Easier, Farther, and Faster–With Fewer Injuries (Rodale, 2017). And now for something completely different–a book on running stride. I’m a sucker for new running books. I can’t say my running has been revolutionized, but then again, I can’t say I’m doing many of the things the book tells me to do. Basically, running form takes work, but if you want to work at it, this book is the place to start.

Gilles Emery, The Trinity: An Introduction to Catholic Doctrine of the Triune God, translated by Matthew Levering (The Catholic University of America Press, 2011). This is a good mid-level introduction for students and pastors to the historic, orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. I found the writing (the translation maybe?) a little hard to track with at times, but the content is excellent (if occasionally more Roman Catholic than I needed).

Cal Newport, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World (Grand Central Publishing, 2016). This would have been on my Top Ten list, except that it was published last year. This was a great book to read while starting a new job (or two new jobs). Like most people my age and younger, I struggle to make the time for “deep work.” Newport provides powerful reasons why I must do this and good suggestions for how I can.

December 19, 2017

Pastor, Don’t Get Cute this Christmas

I know the feeling.

Christmas comes around every year. The same songs. The same texts. The same story. Most of the time I love the familiar rhythm of Advent and the comforting routine of tradition.

But as a pastor, I also know that sense of desperation: “How many more Christmas sermons and holiday homilies can I possibly come up with?” And I rarely do a full four-week Advent series. The poor brother who does an Advent series every year for 40 years is going to preach at least 160 sermons on Christmas. I sympathize with the temptation to novelty.

But don’t do it, pastor. Don’t get cute at Christmas. Your people need regular meat and potatoes, not the newest eggnog recipe. Stay away from props and video clips. Put to death the Star Wars tie-in you’ve been really excited about. Don’t worry about preaching the same truths and the same themes. They don’t remember last year’s sermon anyway. Go ahead and tell them the old, old story one more time.

That means the Christmas Eve service should not be about the evils of shopping or the dangers of busyness. We can leave behind clever cliches like “Wise Men Still Seek Him” or “Have Yourself a Mary Christmas.” There’s no need to focus for 40 minutes on what exactly was the Star of Bethlehem, and if you are going to talk about the Magi, don’t make it an academic lecture on Persian astrology. Let’s spare our people the usual harangue about how Protestants have ignored Mary for too long (even though, I’ve heard that sermon and read those articles every year since I was a kid). Let’s not get caught up in the dating of Christmas or debunking the supposed parallels with Mithras.

Are any of these things wrong in themselves? Of course not. I’ve touched on these themes in a number of messages over the years. But let’s keep the main thing the main thing.

There will be unbelievers at your Christmas Eve service. And struggling saints. And weary souls. And wayward sinners. And stragglers who have ventured into a church for the first time in a long time. They need to hear about Jesus, about the Word made flesh, about the only begotten Son sent from the Father, about the one who fulfilled ancient prophecy, about the one who came to save his people from their sins.

Dear pastor—and I’m reminding myself as much as I’m reminding you—our people don’t need us to find something new. They don’t need empty spiritual bromides. And they don’t need us to brandish our cultural bona fides at Christmas. Our people need the gospel. They need the Trinity. They need to hear about the miracle and the majesty and the mystery of the incarnation. Hunker down in Matthew 1 or Luke 2 or Isaiah 9 or Micah 5 or John 1 or in any text that will lead you to lift high the name of Jesus. Don’t be cute or clever. Just preach Christ.

Your people will be glad you did. And looking back years later, so will you.

December 14, 2017

R. C. Sproul on the Curse Motif of the Atonement

An excerpt from R.C. Sproul’s 2008 T4G message: “The Curse Motif of the Atonement.”

You can watch the whole thing here. One of the best sermons I’ve ever heard.

R.C. Sproul on the Curse Motif of the Atonement

An excerpt from R.C. Sproul’s 2008 T4G message: “The Curse Motif of the Atonement.”

You can watch the whole thing here. One of the best sermons I’ve ever heard.

December 12, 2017

Best Books of 2017

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of Christian books published each year, let alone every interesting book published in 2017. I read a lot of books, but there are plenty of worthy titles that I never touch (and never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year.

When I say “best” I have several questions in mind:

• Was this book well written and enjoyable to read?

• Did I find it personally challenging, illuminating, edifying, or entertaining?

• Is it a book I am likely to reread or consult often?

• Do I see myself frequently recommending this book to others?

Undoubtedly, the “best” books reflect my interests and inklings. This doesn’t mean I agree with every point in all these books, but it does mean I found them helpful and insightful.

One important change from previous years: the ten books are not ranked in any kind of order; they are simply listed alphabetically by author.

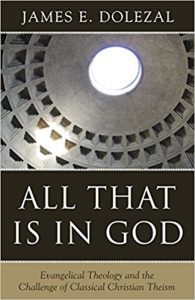

James Dolezal, All That Is In God: Evangelical Theology and the Challenge of Classical Christian Theism (Reformation Heritage Books). “The chief problem I address in this work,” writes Dolezal, “is the abandonment of God’s simplicity and of the infinite pure actuality of His being” (xiii). That may sound terribly technical, but the issues Dolezal raises have huge ramifications for the doctrine of God and what it means to relate to the God who does not change.

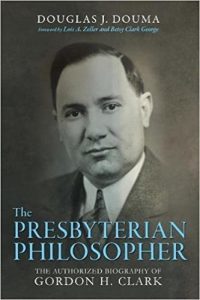

Douglas J. Douma, The Presbyterian Philosopher: The Authorized Biography of Gordon H. Clark (Wipf and Stock). Using a hefty dose of archival sources, Douma does an admirable job helping us understand Gordon Clark the man, not just his ideas. For someone that few people still talk about, Clark played a crucial role in the development (and divergence) of 20th-century Reformed theology and the burgeoning neo-evangelical movement.

Alan Jacobs, How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds (Currency). Jacobs writes well and means to help us think well, arguing that we can actually learn to be less lazy and more thoughtful. A fast, fascinating, and useful read.

Arnold Kling, The Three Languages of Politics: Talking Across the Political Divide (Cato Institute). Another short book filled with plenty of illustrative material. Kling maintains that progressives, conservatives, and libertarians often talk past each other because they each see the world through one particular moral lens: oppressor-oppressed (progressive), civilization-barbarism (conservative), or liberty-coercion (libertarianism).

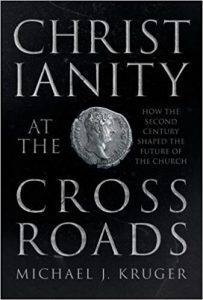

Michael J. Kruger, Christianity at the Crossroads: How the Second Century Shaped the Future of the Church (SPCK). While many books deal with the first century and the historical Jesus, and other books deal with church fathers and doctrinal heresies in the third, fourth, and fifth centuries, there are fewer books that cover the crucial second century. Kruger fills the gap with a mid-level textbook that manages to serve students and still be accessible to interested lay people.

Gideon Mailer, John Witherspoon’s American Revolution (UNC Press). Okay, so you’re going to find this book more interesting if you are doing doctoral work on John Witherspoon. But even if you don’t want 400 pages of detailed analysis on Witherspoon’s relationship to the Enlightenment, Augustine, and the founding of America, it’s still an important book, not least of which because it pokes holes in the received narrative that Witherspoon was a confused thinker who threw off evangelical orthodoxy when he crossed the Atlantic.

David Murray, Reset: Living a Grace-Paced Life in a Burnout Culture (Crossway). I’ve already started to use this book with our elders, and I have recommended it often. Murray is unflinchingly honest and eminently practical. I hope to read back through the book again and share it with my wife.

Tom Nichols, The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters (Oxford). This is not a book long rant against ordinary rubes and common folk. Nichols is well aware that experts are part of the problem. His aim is to bridge the gap between experts and laypeople. A functioning Republic depends on the former serving the latter and expects the latter to pay some deference to the former. To act as if no one knows more than anyone else is not only silly, it’s also a serious mistake.

Fred Sanders and Scott R. Swain, eds., Retrieving Eternal Generation (Zondervan). With contributions from top notch scholars like Lewis Ayres and Chad Van Dixhoorn, this book takes an impressive looks at a neglected doctrine. Every orthodox Christian confesses that Christ is “begotten, not created,” but what does that mean, and why does it matter? This book tries to answer those questions. The chapters by D. A. Carson on John 5:26 and Lee Irons on monogenes were particularly illuminating.

Denny Spitters and Matthew Ellison, When Everything Is Missions (Bottom Line Media). The theme of the book is simple, provocative. and timely: we are not all missionaries and not everything is missions, and if we don’t get these definitions correct we will not be effective in carrying out the mission Christ gave to the church.

December 7, 2017

Immutability and Reformed Theology

I wrote last week about James Dolezal’s important book All That Is In God. The book continues to generate spirited discussion, with a growing number of blog posts populating the internet.

In an effort to promote more light than heat, I thought it might be helpful to compare two different approaches to the doctrine of immutability: one from Herman Bavinck and one from John Frame. I am working with these two authors because Bavinck (of older theologians) is especially detailed when it comes to immutability, and because Frame (of more recent theologians) is so widely read and respected. He has also taken considerable interest in Dolezal’s book. While my sympathies lie with Bavinck, I’m going to refrain from arguing one view over another. Instead I hope to fairly represent both theologians, noting where they agree and disagree.

Bavinck on Immutability

Bavinck recognizes that at first blush immutability seems to have little support in Scripture (Reformed Dogmatics 2:153). Does not God, in the first chapter of the Bible, move from not creating to creating? Is he not a coparticipant in the life of the world? Bavinck cites dozens of Bible verses to show that God repents, changes his plans, becomes angry, sets aside his anger, and shows himself to be friend or foe depending on the attitude of his creatures (cf, Gen. 6:6; 1 Sam. 15:11; Num. 11:1; Deut. 13:7; Exod. 32:10-14). Moreover, God became human in Christ and dwells among us through the Holy Spirit, both examples seeming to suggest change in God.

Amid all this alteration, however, Bavinck insists that the God of the Bible is and remains the same. Here again, Bavinck cites dozens of passages showing that God is who he is, remains the same, has no variation or shadow due to change, does not change his mind, and always does what he says he will do (cf. Isa. 41:4; 43:10; Deut. 32:39; 1 Sam. 15:29; James 1:17). In short, God does not change (Mal. 3:6).

For Bavinck, immutability is what it means for God to be God. He is eternal, necessary, free from all composition, and devoid of potentiality; he is pure act, pure form, unadulterated essence. “If God were not immutable, he would not be God” (RD 2:154). As the God who is, he cannot change, for any kind of change would diminish his being. “All that changes ceases to be what it was. But true being belongs to him who does not change” (RD 2:154). Importantly, Bavinck makes clear that neither creation, nor revelation, nor the incarnation brings about any change in God.

This doctrine, Bavinck maintains, has been taught “in the scholastics and Roman Catholic theologians as well as in the works of Lutheran and Reformed theologians” (RD 2:154-55). By contrast, those who oppose immutability include deists, pantheists, Pelagians, Socinians, Remonstrants, and rationalists. Orthodox theologians have held that God is unchanging in essence, knowledge, and will.

Furthermore, Bavinck argues that we must not soften immutability by locating it in ethical realm only, or by insisting that God is his own cause (causa sui) of actualization (RD 2:156-57). Every change is foreign to God, whether in time, in location, or in essence. God is pure actuality (pursus actua), a perfect and absolute being without any capability (potentia) for nonbeing or being different than he is (RD 2:157).

The very idea of God implies immutability. “The difference between the Creator and the creatures hinges on the contrast between being and becoming” (RD 2:156). Divinity, by definition, cannot change for better or for worse. God is not just a kind of being; he is true being. And as such, there can be no becoming in God, no form of change in time or space. “Those who predicate any change whatsoever of God, whether with respect to his essence, knowledge, or will, diminish all his attributes: independence, simplicity, eternity, omniscience, and omnipotence. This robs God of his divine nature, and religion of its firm foundation and assured comfort” (RD 2:158).

Of course, Bavinck reminds us, this immutability must not be confused with rigid immobility. “While immutable in himself, he nevertheless, as it were, lives the life of his creatures and participates in all their changing states” (RD 2:158). The phrase “as it were” is key for Bavinck. He does not believe God actually changes, but he fully appreciates how Scripture describes God’s relational life in anthropomorphic language. “There is change around, about, and outside of him, and there is change in people’s relations to him, but there is no change in God himself” (RD 2:158). In fact, because God is immutable—true being without any potential for nonbeing or for change—he can call mutable creatures into being. Though eternal in himself, with no before or after, God engages the temporal world, condescending as transcendent God to dwell immanently in all created beings (RD 2:159).

Frame on Immutability

Frame begins with an overview of the main scriptural references to God’s unchangeability (Systematic Theology 367). He cites many of the same passages as Bavinck, from Psalm 102:25-27 to Malachi 3:6 to James 1:17. Frame reaffirms that God’s decretive counsel stands firm and his purposes always come to pass.

Following this brief synopsis, Frame enters in to a lengthy discussion about the “problems that arise in discussions of God’s unchangeability” (ST 368). Citing texts like Exodus 32:9-10 and 1 Samuel 15:35 and Joel 2:13-14, Frame concludes that “relenting is part of his very nature as the Lord. He is the Lord who relents” (ST 368-69). But this does not mean there is change in God’s divine nature. Frame recognizes there are also passages that deny that God relents (1 Sam. 15:29). God may relate to his creatures as a relenting God. And yet, this does not undermine his sovereignty, because while God’s decretive will may be disobeyed, his eternal purposes always stand. In fact, God’s eternal plan means to use human actions and prayers. In other words, there is a way for God to remain unchanging in his essence and will while still sharing a “give-and-take” with human beings “in his temporal immanence” (ST 371).

With this discussion in the background, Frame argues that the attribute of “unchanging” needs careful definition, since “Scripture attributes to God some kinds of changes, even changes of mind” (ST 373). Some of these changes are mere “Cambridge changes,” a change that is not a real change but a perceived change based upon all that has changed in relation to that which is unchanged (i.e., the weather gets hotter not because the sun grows but due to the rotation of the earth, the revolution around the sun, the dissipation of clouds, and so on). Frame admits some divine change language in the Bible can be understood this way, but certainly not all (ST 373).

So what about God is unchanging? Frame lists four things: his essential attributes, his decretive will, his covenant faithfulness, and the truth of his revelation (ST 374-76). In these four ways, God always remains the same. Creatures change, but God does not. He does not increase in knowledge or power. He is supremely perfect in all his attributes and utterly trustworthy in all that he promises.

And yet, in another sense, we must speak of God changing. In his atemporal or supratemporal existence (outside of time or beyond time), God is immutable. “But when God enters time, as theophany, incarnate Son, or merely as present in time, he looks at his creation from within and shares the perspectives of his creatures” (ST 376). As God is with us, then, he is able to look at events as past, present, and future. “He views the passing of time as we do, as a process” (ST 376).

This means that we should not write off all the “relenting” language as simply “anthropomorphic.” While there is “some truth in that description” as it describes things from an atemporal perspective, the anthropomorphic label is not helpful in describing God as an actor in history. Here God’s activity is closely analogous to human behavior. As an agent in history, God himself changes (ST 377). “God is not merely like an agent in time. He really is in time, changing as others change. And we should not say that his atemporal, changeless existence is more real than his changing existence in time, as the term anthropomorphic suggest. Both are real” (ST 377).

Key to Frame’s understanding of immutability is the difference between “God’s atemporal and historical existences” (ST 377). From the beginning of creation itself, God has acted in temporal sequence. He creates and names from one creation day to the next, acting and responding to his own act, changing his interests over time according to his unchanging plan (ST 377). While Frame acknowledges that his approach to immutability “bears a superficial resemblance to process theology, which also recognizes two modes of existence in God,” he excoriates process theology for having an impersonal God whose transcendence and omniscience are diminished beyond scriptural recognition.

Compare and Contrast

So what can we say about the doctrine of immutability in Bavinck and Frame?

There are a number of important similarities.

Both handle the same biblical texts, recognizing that divine immutability is taught in a number of passages, while also recognizing that many verses speak of God relenting, repenting, or otherwise seeming to change.

Both agree that God is unchanging in his essence, knowledge, and will. God’s attributes do not change. His understanding cannot grow or diminish. His eternal purposes will always stand and can never be thwarted.

Both affirm that for God to be God he must be without change (in some sense). At the same time, we must allow (in another sense) that God participates in life with his creatures.

Much more could be said about the similarities. Their shared insistence on the importance of immutability should not be taken for granted.

And yet, the differences between Bavinck and Frame are not insignificant.

Their rhetorical structures as almost exact opposites. Bavinck starts briefly with the problem of a relenting God, but then spends most of his discussion emphasizing the importance of immutability. Frame starts briefly with the reality of immutability, but then spends most of his discussion explaining how we must take seriously the relenting side of God. Even if many of their overall points are the same, the errors they feel burdened to combat are quite different.

Frame does not employ scholastic terms like pursus actua, potentia, and causus sui.

Bavinck has no place for affirming change in God himself. People and things change in relationship to God, but any description of God changing must be understood anthropomorphically. By contrast, Frame considers the anthropomorphic label too weak to describe how God relates to the world he has made. As an actor in history, God himself changes.

This last point—which is a significant difference itself—underscores an even bigger difference between Bavinck and Frame. For Frame, God has two different modes of existence: an atemporal existence in which he does not change, and a temporal existence in which he does change. And both existences are real. “God is inside and outside of the temporal box, a box that can neither confine him nor keep him out” (ST 367). Consequently, Frame can affirm that while God does not change in his essence, knowledge, or will, as an actor in history God experiences changes just as we do (or something very close to it). As for Bavinck, he too is eager to make sure that God’s transcendence does not swallow up his immanence. God is not eternally static, he says, neither inert nor immobile. Indeed, God is present in every moment of time (RD 2:163). But this does not mean God has a temporal existence alongside an atemporal existence. Rather, it means “God pervades time and every moment of time with his eternity” (RD 2:164). God does not need a separate temporal existence in order to relate to temporal beings. He cannot be subject to time, measure, or number and still be God. His eternity is an eternal present without past or future. In short, “He remains eternal and inhabits eternity, but uses time with a view to manifesting his eternal thoughts and perfections” (RD 2:164).

One can see how these differences in the doctrine of immutability quickly touch (and are touched by) a host of other attributes. Competing views of immutability are bound up with competing notions of infinity, impassibility, and simplicity. Take simplicity, for example. If God is whatever God has, as the traditional doctrine states—that is, if every attribute of God is identical with his essence—then it does not make sense to say that God can undergo a change of any kind (atemporal or temporal) that does not also imply a change in essence. There is no change that is accidental to God because divinity is, by definition, that true being which can admit no accidents. Likewise, if God takes on new qualities viz a viz his interaction with creation (i.e., if God begins to be Creator or begins to experience intrinsic time or begins anything he did not already have), it calls into question God’s infinite perfection.

But I’m getting into Dolezal’s argument when I said I would stay clear of evaluation. So, let me close this post as I did the last by reiterating that there are real differences here about key doctrines. If we can be clear about what those differences are, we can start to analyze whether the differences are insurmountable and how each position squares (or not) with the Reformed tradition and with the Bible.

December 5, 2017

Voting in a Two-Party System: Ten Other Questions to Ask

This is not about any particular candidate or contest. Every election will have special features and personalities to consider. What’s necessary for Christians, then, is to step back from the hoopla of Right Now! and try to develop some big-picture principles for making difficult voting decisions.

Let’s assume that in the United States at present we are going to have a Democrat or a Republican win virtually every election, especially at a state or national level. And let’s also assume for sake of this article that one party is more clearly aligned with your political, cultural, and ethical convictions. Furthermore, let’s stipulate from the outset that there are no perfect candidates—no one gets everything right, not politically or personally. Voting is simple when the party you like more puts forward a candidate whose character, convictions, and competence you can trust.

But how should we think about voting when the party you like more puts up a candidate you have a hard time liking at all?

A few questions to ask

1. Is this really a choice between two evils? If so, don’t vote for either. Christians should never choose sin. Period. Am I saying then we never vote? No. I’m saying that the phrase “lesser of two evils” may not be the right one. Perhaps we really mean “the less bad of two bad options.” But if we are really making an evil choice, we shouldn’t do it, no matter what party might win with or without our vote.

2. Do I believe that the candidate’s character, convictions, and competence are such that I can reasonably expect that he will make good decisions once in office? The parties matter, but ultimately individual politicians cast votes.

3. Do I believe the candidate will represent me and my beliefs tolerably well? Politicians do more than just vote. They give speeches, they offer commentary, they shake hands, they meet with national and international leaders. Even if we are pretty confident one candidate will share our beliefs more than another, we have to ask what sort of spokesman and representative he will be for our side (and I’ll just use “he” for this post, even though it could be “she”).

4. Is there a threshold of sound character and good judgment without which I cannot cast my vote? Maybe your answer is no. “I’d vote for Al Capone over Hitler,” you might reason to yourself. But for others the answer is, “Yes, I cannot vote for someone who does not possess a minimum standard of decency and reason.” If so, you’ll need to flesh out what that minimum standard looks like.

5. How might voting for a bad candidate affect my preferred party and positions in the long term? Assuming we want more than just victories this election cycle, we have to think about more than short-term gains. Some officeholders, by their ethical folly or political incompetence, end up sullying their party’s reputation and causing good ideas to fall into disrepute. Not every win is a win.

6. What message do I send my preferred party if there are no candidates so bad I won’t vote for them? If there is no minimal standard of character and competence to be met in order to win someone’s vote, over time we will likely end up with worse and worse candidates. Sometimes voting for none of the above or writing in another candidate is better in the long run than voting for one of the two parties that (almost) always wins.

7. Will my vote normalize behavior or ideas that should not be tolerated? Elected officials, by definition, hold public office. As representatives of thousands or millions of people, they have the potential to inspire us with their courage and thoughtfulness or “define deviancy down” by their moral bankruptcy.

8. Have I begun to defend in my party’s candidate what I would never defend were he in the other party? As Christians, the goal is not political victory at all costs, but integrity, honesty, and consistency.

9. Am I casting my vote for someone who will damage the reputation of Christ and may harm the cause of Christ in the world? While it is often good to vote for other Christians, we have to consider how someone conducts himself in public as a representative of Christian convictions, ethics, and character.

10. Am I willing to consider that thoughtful Christians may answer some of these questions differently than I would? I certainly have my opinions about how these questions might apply in specific instances, but more than a particular vote, I want to encourage Christians to think critically and strategically about their civic participation. There is more to consider than majorities for our side and defeat for theirs.

November 29, 2017

All That Is In God

As a blogger I get sent a lot of books. Sorry to say, I throw away some of them, shelve most of them, and read only a few of them. Most of the books actually look halfway decent, but there just isn’t time to read everything that comes my way. So when Reformation Heritage Books asked me this summer if I wanted an advance copy of James Dolezal’s All That Is In God, I said “sure,” not expecting much to come of it.

Turns out this is a really important book. Although the text is less than 150 pages, the content is sharp, dense, and bound to generate some controversy. Dolezal, a Reformed Baptist who teaches theology in the School of Divinity at Cairn University (Langhorne, PA), has done the church a favor in raising such crucial issues in such a short book, one that is philosophically technical but still readable for the pastor or seminary student. It’s for good reason the book comes with glowing blurbs from Richard Muller, Paul Helm, and Scott Swain.

So what is this book about? Let me try to give a brief summary and then an offer a brief evaluation.

The Challenge of Classical Christian Theism

“The chief problem I address in this work,” writes Dolezal, “is the abandonment of God’s simplicity and of the infinite pure actuality of His being” (xiii). The simplicity of God means God is not made up of his attributes. He does not consist of goodness, mercy, justice, and power. He is goodness, mercy, justice, and power. Every attribute of God is identical with his essence, which also means that although the attributes of God are revealed to us as varied, they are (on the God-side of knowing) identical with one another.

God is whatever he has. He is not the composite of his attributes, some in greater and some in lesser amounts. God is a simple being without parts or pieces. As Bavinck puts it: “If God is composed of parts, like a body, or composed of genus (class) and differentiae (attributes of different species belonging to the same genus), substance and accidents, matter and form, potentiality and actuality, essence and existence, then his perfection, oneness, independence, and immutability cannot be maintained” (Reformed Dogmatics 2:176). In other words, if you tug at the thread of simplicity, a lot of classical Christian theism is going to unravel.

Dolezal’s concern is to defend the immutability of God. Because God is simple and always active (and never passive), “God is not capable of receiving new determinations or features of being—not even if He sovereignly chooses to. Any change in God, even a nonessential one, would introduce new being or actuality into Him” (xiv). The line “even if He sovereignly chooses to” is key to the polemical purpose of the book. Dolezal is concerned that “evangelical mutualists,” among them conservative Reformed theologians we respect, want to portray God as immutable and mutable, impassible and passible, simple and complex, timeless and temporal (7). Not wanting to make the same mistake open theists do—dialing down divine omniscience and divine sovereignty—Calvinistic theistic mutualists argue that God can undergo relational and emotive changes because God himself wills these changes (29). Any changes in God are nonessential changes because they are changes freely chosen.

Dolezal objects to this popular retelling of immutability and impassibility. With the doctrine of simplicity, classical Christian theists have maintained that there is no such thing as a nonessential change in God (i.e., a change that does not touch the essence of God). Every state of being is an ontological state, such that any change in God, even one freely chosen, implies an essential change. Divinity is, by definition, unable to grow, to develop, to move from one state to another, because anything less than pure actuality means God needs someone or something else in order to be fully God. “Because God cannot depend on what is not God in order to be God, theologians traditionally insist that all that is in God is God” (41).

In summary:

[T]his strategy of denying essential change while admitting nonessential change in God is not available to those who claim to hold to a classical conception of immutability or divine simplicity. This is because according to the simplicity doctrine there is nothing in God that falls outside of His essence or is really distinct from it. When theologians in the classical tradition deny essential change in God, they mean to deny all change in God whatsoever—because there is nothing in Him that is not identical with His essence. Modern evangelicals who offer a model of God as both essentially immutable and nonessentially mutable have effectively abandoned the doctrine of God’s simplicity. They presume that there is some accidental actuality in God that exists alongside His essence. (97)

This mutualist understanding of God is not a minor tweak on classic theism or another way of saying the same thing. Instead, Dolezal maintains that the two views have very different ways of relating God to time, of relating God to his creatures, and of understanding the relations (not relationships) of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These are not small disagreements. However much we may want to champion God’s relatability and intimate compassion, deviating from classical theism is not the way to do it.

Evaluation

The short version of my evaluation goes something like this: I agree with Dolezal and applaud his defense of divine simplicity, immutability, and impassibility, which is why I assigned All That Is In God for my Systematic Theology class this fall.

To expand on that evaluation just a bit, let me make three other points.

1. Dolezal could have helped his case by describing the men he wishes to critique with more nuance. As John Frame points out, Dolezal names a lot of impressive names, including James Oliver Buswell, Bruce Ware, Alvin Plantinga, John Feinberg, J. I. Packer, Kevin Vanhoozer, and, yes, John Frame. While there is nothing wrong with mentioning specific men, even men we like and respect, at times it seemed like anyone who has ever been soft on impassibility or simplicity got lumped in as a theistic mutualist. Dolezal has written a polemical book, and perhaps the issue calls for some polemics, but I’m not sure the combativeness was warranted in every instance.

2. This is a work of systematic, philosophical, and historical theology. To be sure, there is interaction with Scripture at key points. Dolezal is certainly concerned to be biblical. And yet, I think it’s fair to say this is not a piece of exegetical theology. That doesn’t make it wrong by any means, but it does mean some readers will walk away saying, “Yeah, but what all those verses that seem to describe God’s emotional life or his in-time dynamic relationship with his creatures?” This is one of the points Joseph Minich makes in his largely positive review. Dolezal’s response is that Scripture speaks of God anthropomorphically and anthropathically. Dolezal rejects a univocist approach to theology in which we presume that our language about God—in it’s propositional claims and in its forms and modes—literally describes God’s intrinsic act of being (as opposed to the view that says our language about God is true but must not be understood in the same way we might use the same language with reference to human beings). This response is right and salutary, so long as we don’t flatten the contours of Scripture and grow uncomfortable talking about God the way the Bible talks about God.

3. The strength of Dolezal’s work is in recovering the traditional, orthodox convictions which underlie classical Christian theism. As much as I have appreciated many of Frame’s books over the years, his vigorously critical review not only assumes the worst about Dolezal’s motives and conclusions, it pigeonholes the book as nothing but “scholasticism for evangelicals.” Frame chides Dolezal for going against the contemporary consensus of so many fine evangelical scholars. Fair enough, but Augustine, the Cappadocians, the Medieval Schoolmen, and the entire tradition of Reformed Orthodoxy from Turretin to á Brackel to Bavinck is squarely on Dolezal’s side. As Mark Jones puts it, “Not only Aquinas, but patristic, medieval, Reformation, and Post-Reformation Reformed theologians are basically with Dolezal and not the very recent group of authors that Frame calls a ‘consensus.’ The men who wrote the Westminster Confession would certainly join with Dolezal over the revisionist theology that seems somewhat popular in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. After all, they were all Reformed scholastics.” Besides, if Richard Muller has taught us anything, it’s that “scholasticism” speaks of method more than of content. The terms, delineations, and distinctions stretch over many centuries. The convictions about simplicity and pure actuality did not begin or end with Aquinas.

Conclusion

I hope pastors, seminary students, and professional theologians will read All That Is In God and carry on the important discussion Dolezal has raised so effectively. It’s cliche to talk about the “conversation,” but when done well we really can learn from the push and pull that comes from rigorous, yet irenic, theological debate. If nothing else, we should all agree that the doctrine of God is not an insignificant matter in Christian discipleship. If something has been amiss in recent evangelical theologizing about God, we would do well to know what that is.

November 22, 2017

The Thanksgiving that Was (and Was Not)

On the way to Jerusalem he was passing along between Samaria and Galilee. And as he entered a village, he was met by ten lepers, who stood at a distance and lifted up their voices, saying, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.” When he saw them he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went they were cleansed. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice; and he fell on his face at Jesus’s feet, giving him thanks. Now he was a Samaritan. Then Jesus answered, “Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine? Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” And he said to him, “Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.” (Luke 17:11-19)

The painting above, “Ten Lepers,” is by the Mormon artist James Christensen. While I don’t share the same faith, I have always found this to be a moving piece, which, like all good art, prompts one to look, to linger, and to reflect.