Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog, page 8

March 5, 2011

Party Down

It's a strange custom, all right.

It's a strange custom, all right.1. Go to the store and spent a large wad on viands, wine, sweets, candles. Oh, and olives. Got to have olives.

(In days of yore, more or less the same thing: Snare rabbit; dig up potatoes; chop wood for stove.)

2. Spend the entire day rinsing, dicing, marinating, sauteeing, and baking.

3. Chance to go into downstairs bathroom; gasp. Run get broom and Comet cleanser.

4. Just after dark, make sure outdoor lights are on (insurance), switch on Pandora. put match to candles.

5. Wait to see headlights in your driveway or dog to start barking madly, whichever comes first, or simultaneously.

6. Four hours later, so tired you'd gladly fall into bed still wearing your shoes and earrings, embark on an hour and a half of continuous wineglass washing, pot scrubbing, spill wiping. Vow never to do this again. The next day, start remembering only the great things, and go get calendar to find next open Friday night.

The custom is the dinner party. How long has it been going on? How long have we been craving this admixture of preparations and anticipation, work and giving, chatter and smiles, laughter and consumption, together? Friends in the kitchen: there is nothing so deeply desired at times, and nothing so deep.

There is something in the dinner party that is both highly refined--codified, even, from the moment of entry with proffered bottle in outstretched hand at the same moment as the happy greeting, through the hour of cheese and crackers (and olives), to the first forkful and the praise--and stone primitive. It's huddling around the fire and the roasted bits of torn rodent inside the cave, washed in eons of bathwater until it comes out smelling of candlewax and chevre, martinis and chocolate mousse.

After a while I start to itch if I haven't given one, or gone to one, in some time: last weekend was a scratch-fest. On Friday, at my house; on Saturday, at others'. Of course, this means dual dinner parties both nights, as there are children aplenty. You cook first for them (Friday night, nachos; Saturday, pasta), then put them in front of a movie, where they will be held rapt so the grownups can finally move to the table, sit down and refill the wineglass. We talk, talk, talk--about what? It doesn't matter. It's connection. We are as hungry for it as for the food (menu: mixed seafood; red potatoes roasted with rosemary; spinach with feta, washed down with sparkling wine, to toast a friend who will have a solo show of art in New York next month). Some of these friends are seen at dinner parties, so dinner parties there must be.

(Nelly, too, partied down. Or shall I say up: near the end of the evening, she figured out how to get on top of the breakfast-room table. Which is where the kids had left their many plates of half-eaten cake. Nelly was now grazing, very much like a cow or horse, moving from plate to plate. This means that forever after, I must be vigilant about pushing the chair all the way up to the table, so as not to give her a stepladder to Nirvana. Do you think I will be able to remember? Your vote counts. Well, at least she made this brilliant advance in her knowledge base after the cake had been served, rather than before.)

Every element of the ritual we have long called "dinner party" stands for something. It's like a church service. The giving of time, and trouble; the receiving of hors d'oeuvres. The hellos and goodbyes, and something in between: humanness, elemental. We state our needs outright. I need sustenance. I need you. I don't know--do you crave this too?

Published on March 05, 2011 05:22

February 26, 2011

At the YMCA

Recently, I joined the YMCA in "the big city." The term is relative: I live in a hamlet so small its sole businesses are two pizza parlors, two gas stations, one wine store, and an unspeakable "Chinese" takeout (you see where our priorities lie). The city that has vastly more gas stations, pizza parlors, liquor outlets--as well as the Y--is twenty-five minutes away.

Recently, I joined the YMCA in "the big city." The term is relative: I live in a hamlet so small its sole businesses are two pizza parlors, two gas stations, one wine store, and an unspeakable "Chinese" takeout (you see where our priorities lie). The city that has vastly more gas stations, pizza parlors, liquor outlets--as well as the Y--is twenty-five minutes away.This town is Kingston, New York, on the mighty Hudson. It is an undiscovered gem. I like the fact that parts of it feel like I alone know them--this sense of ownership of discovered things that appeared to be waiting for one for a hundred years is what made New York City in the seventies and eighties such a paradise in which to be young and poor. I also like the fact that lately a few enterprising folks have seen the promise in Kingston's situation, above the river, with unremodeled nineteenth-century buildings (and more than a few ghostly seventeenth-century stone houses, too) so that now, in uptown, we have a couple of gently hipsterish restaurants and one of the most awesome bars ever (so awesome, in fact, it renders me speechless but for teenage gibberish like "awesome"). The rest can stay undiscovered, and mine . . . now that I've got my hand-made cocktails and raw oysters.

Then there is midtown Kingston. Poor, poor midtown. The summer after I graduated from college, I went to visit friends, a couple who had taken an apartment somewhere. He (who would later become an architect in the true big city) gave me directions to a place I'd never heard of before. I simply drove, glancing down at the paper in my hand, until I got there. Later, I didn't even remember what city I had gone to, or in which direction, only that it was about an hour from the town in which we'd gone to school.

I do remember thinking I had to be lost. This, this . . .depressed landscape of ugliness, emitting hopelessness from every lopsided, peeling building, nary a tree in sight, could not possibly be where anyone--much less a couple of young bright stars just out of a very good college--would choose to live. It was the kind of place people no longer bothered to dream of getting out of; it was so bootless, and so they continued to shuffle up and down the wide avenue, their horizons ever the same, and ever gray.

Twenty years later I was talking to my friend and thought to ask, "Hey, where was that that you guys were living the summer of '80 and I came to visit you?"

"Broadway in Midtown Kingston," he replied.

"Trust me, it will never change," he added.

This is thus the perfect location for the YMCA, an institution that was founded in industrializing London, where in 1844 workers faced a bleak and filthy future. George Williams, 22, was concerned and wished to offer a farther horizon (and some Christian saving) to the men coming to the teeming city from the countryside. (In Boston in 1851 the first American Y was created, by a retired sea captain.) It now promises "strong children, strong families, strong community." Midtown Kingston needs it.

I need it, too. The Y is no-nonsense, and every single type of person makes use of it. In the parking lot you'll see Audis and Hyundais, Volvos and Scions, as well people waiting outside for a ride because they have none of their own. We'll all equal inside the walls of the Y: we're fat and thin, young and old, black and white. Signs in the teen center remind kids to be respectful of one another, no dissing allowed. People say hi with a smile, and mean it. As there are in the tumbled-tile locker rooms of a posh spa, here there are no cotton balls, Aveda hand lotion, or basket of tampons in individual protective cardboard cases (BTW, lady motorcyclists, take these when you find them: one day you'll be very glad you remembered you put one in the tankbag). Eh. Who cares. Anti-elitism is the best medium in which to grow, even if the faint odor of mildew that hangs over the pool and the strange smell that greets you when you open the door to the steam room knock you back temporarily. But then you quickly get down to business. We're here to swim, and to sweat. And occasionally to say hi, smile, and mean it.

Published on February 26, 2011 06:51

February 19, 2011

Wakeup

I am, and then I am not.

I am, and then I am not.The magazines piled up on my bedside table through the winter: BMW ON, Cycle World. They had something colorful on their covers each month--what were those things? They had two wheels, and what looked to be some sort of human crouching, lizard-like, on top of it, clutching something in each outstretched hand. Huh.

The snow piled up against the garage doors. Occasionally I would beat my way to one, throw it up, to get the skis, the sleds. The garbage can, to go to the dump. Large gray-covered shapes, I was vaguely aware, were also there; I would glance over to make sure there was a glowing green diode on a small black box sitting on the floor next to one of them, attached by orange extension cord snaking toward the outlet on the wall. Then bang, the door went down again.

I was not. But now, the temperature rising bit by bit and the snow beginning to darken the pavement of the driveway with slowly expanding water, I am.

I am a motorcyclist again. I stayed up till midnight last night, suddenly possessed by the contents of one of the magazines, which I at last cracked open and could not stop reading. Here's the rally I will go to. Here are the tips for riding better, and here is the endless stream of information of all types, too much, too much to absorb. I am suddenly feeling the initiation of a turn, the downward pressure on a grip, the magical balance of weights moving places, becoming something else. I am thinking about tires again.

(How is it that, several feet distant, you can feel your tires, every molecule of their being, though you are made of different stuff?)

I had entered a fugue state, I realize now with appreciable surprise. And with the coming of spring (its warming promises), I am becoming something else too. At long last.

Published on February 19, 2011 05:02

February 12, 2011

Finally

The obituaries, although the last thing, are the first thing for some people when they open the paper. They exert some strong pull on certain readers--gratitude, perhaps, or schadenfreude, or proof that indeed life can describe a fully comprehensible arc, when laid out in 10-point type and finished off (if invisibly) with the words "The End."

The obituaries, although the last thing, are the first thing for some people when they open the paper. They exert some strong pull on certain readers--gratitude, perhaps, or schadenfreude, or proof that indeed life can describe a fully comprehensible arc, when laid out in 10-point type and finished off (if invisibly) with the words "The End."I myself was never drawn to read them. It always felt like I was reading a review of a show that had already closed: what if I realized, too late, that I wanted to go?

Something has changed now (yeah, it's that view of My Obituary Time in the distant circle of the spyglass). So I find myself scanning them now with a certain mathematical interest. I calculate the average from the ages of demise on any given day: 82, 78, 85. I can't help it; it just happens, and . . . Whew. I still have a decade or two! As if the newspaper is a prognostigatory tool. As if it's all about me.

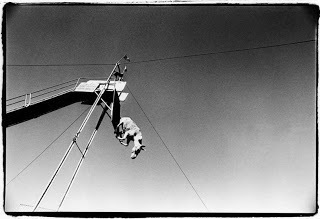

The other day, though, an obituary caught my eye and held it: "Parasailing donkey dies of heart trouble." The lede read, "Moscow.--The Russian donkey whose brays of terror while parasailing won her worldwide sympathy has died."

I'm afraid I didn't have the heart to look for the YouTube clip that got her such sympathy; I spent many years when I was younger and stronger--and apparently hopeful enough to believe that knowledge was the power behind change--looking at pictures and reading academic papers on the endemic torture of animals that seems to be a human birthright. I am too brittle now. Just reading those words, brays of terror, started a sickening loop in the auditory imagination.

The other day an image flashed on the inward screen, and it coincided with (or was precipitated by) a week in which I found myself thinking, longing, again for the touch of a horse. It's been a long time. Horses are nothing that you can break the addiction to that easily; the nicotine of the animal world.

That's when I suddenly saw myself looking once more out the bedroom window of the old house--a place I do not think much about anymore, being a resolutely forward kind of person, ha, except when I yearn for the kind of expansive summertime yard party for several dozen of kids and wine-happied parents I used to be able to have--to the tumbledown barn out back. This was to be fixed up, risen from the dead, to become itself again. It was the place to which my hopes flew like swallows. Someday, I knew, I would complete that view with some horses and donkeys. It would remain largely a view, for I would only feed them, and brush them, and spend secret moments, muzzle to muzzle, breathing sweetness from their nostrils. The rest of the time they would lead their own lives--that which was taken from them before. For they would be ex-circus, ex - carriage horse, ex-racehorse, ex - kill pen. We would grow old together, nothing ever placed on our backs again.

Just a few. Just a few of the many, the too many, who had expelled their own brays of terror, or silent prayers for surcease. A few, given some good time to help wash away the memory of what had happened before. I believe they would have forgotten easily, out there in the pasture beyond my window. Because they, like all of us, naturally face forward too.

This is because, as I have found, all heartache passes. Except for a vague residue barely felt, weightless, almost. After a time, you barely remember what caused it, or why.

The obit mentions that near the end, Anapka the donkey spent her final months on a farm outside Moscow "in luxury." She deserved it, and more, though the heart trouble she was made to suffer proved more durable than most experienced in the usual course of life. Then came the blessing that is finally offered to us all, but only, it is hoped, after uncounted mouthfuls of green grass ripped fresh from the ground.

The End.

Published on February 12, 2011 06:11

February 5, 2011

The Revisitation

I am in the peculiar position of finally rereading--not by choice, but as an editorial assignment-- a book I last read just after I wrote it over fifteen years ago, and the experience is deeply unsettling. I wish I could say this is because of the evidence of how entire large swaths of my own life have vanished from memory, though there is that bit of uncomfortableness. No matter; here they are again. The moments come right back in all their fullness: I am on the Parkway again for the first time. Now I feel that warm grass on the back of my head, while above is the impossible and great blue, with the kind of sweep and saturated color they only make in the South. Here too is a lonesome night in Germany (see? you got through that all right!), cut adrift from all that I knew. Oh, and I had forgotten ever riding through that white sleet, so surprising; and getting lost in a foreign country; and worrying about where to park, when I knew I could not afford anything to happen to a bike I simply had to sell when it was time to leave.

I am in the peculiar position of finally rereading--not by choice, but as an editorial assignment-- a book I last read just after I wrote it over fifteen years ago, and the experience is deeply unsettling. I wish I could say this is because of the evidence of how entire large swaths of my own life have vanished from memory, though there is that bit of uncomfortableness. No matter; here they are again. The moments come right back in all their fullness: I am on the Parkway again for the first time. Now I feel that warm grass on the back of my head, while above is the impossible and great blue, with the kind of sweep and saturated color they only make in the South. Here too is a lonesome night in Germany (see? you got through that all right!), cut adrift from all that I knew. Oh, and I had forgotten ever riding through that white sleet, so surprising; and getting lost in a foreign country; and worrying about where to park, when I knew I could not afford anything to happen to a bike I simply had to sell when it was time to leave.I am startled to meet myself again in these pages, but it is not due to forgetting so much that I had done in so many places, in so many frames of mind. The alarm comes from suddenly seeing a person I wish that I could forget: the person who wrote them. I long for the eraser that could blank out whole paragraphs, this comment or that, this smugness or that secret better left unsaid. I was like a bulldozer of experience, too sure, and wrong about so much. I misread my own life, and though I see that with a painful clarity now, there is also the awful sense that the off-kilter assessments came from some obdurate part deep inside, running my full length, that I cannot and will never change, no matter how many hours I spend sobbing (or nodding) in therapists' offices.

I keep coming full circle, again and again, to the past that is me, to the me that is past.

So many say change is simple: Just do it. Yes, just decide to change, and presto. New person. One who does not find a part of herself sheared away and watching in sadness and dismay as she does--again--what she had vowed never to repeat. It is at these times that I feel I am but a subterranean riverbed through which run the old incessant waters of my family past, back, back down the lineage, all the way to those sepia people in the old photograph on my wall, standing silently, waiting for the shutter to close, in the side yard of a farmhouse somewhere in Ohio. People I never knew, but whose stern words and angry actions and private sadnesses were passed down, hand after hand, and now lie inside me, waiting for the match to touch the fuse.

Although it seems contradictory, I am a biological determinist when it comes to the human race; but I believe absolutely in nurture over nature when it comes to the individual. A behaviorist when it comes to the formation of the personality; and a Freudian when it comes to how it all comes down. How it is remembered, and repeated.

Maybe what ones writes should never be reread. Or maybe just not when one is in a mood. These pages to me now have the feel of the communion wafer, dry and tasteless, but actually a metaphorical food, full of body and blood.

Published on February 05, 2011 05:26

January 29, 2011

Face It

In the late eighties, New York Telephone got themselves a good slogan: "We're all connected." It warmly evoked all the paradoxical longing and anxiety of the ring-and-answer dialectic. There was something a little scary in the thought. At the time, I wrote a poem to someone that conveyed the desire, and the horror too, and I think there was a line in it that went "Oh my god: we're all connected."

In the late eighties, New York Telephone got themselves a good slogan: "We're all connected." It warmly evoked all the paradoxical longing and anxiety of the ring-and-answer dialectic. There was something a little scary in the thought. At the time, I wrote a poem to someone that conveyed the desire, and the horror too, and I think there was a line in it that went "Oh my god: we're all connected."In a new era, now, there's something exponentially more frightening, and you use it, and I use it, and we all use it, and oh my god we're all connected by Facebook.

Frankly, it scares the wits out of me. Just as I am frightened by anything big--a rogue wave, say--coming at me whose power I do not comprehend.

The feeling is a bit like that which arose before setting out for a party when I was in my twenties: Who's going to be there? Do I look all right? Maybe no one will want to talk to me. Maybe everyone there will be smarter, prettier, funnier. Maybe I will slink home without having said a word.

On Facebook, all of that is indeed the case. I am paralyzed into silence by the shiny wit and compact humor and alchemical apercus, expressed in sentences as verbally layered as paratha bread, of so many of my friends: these are people who should have been stand-up comics or political speechwriters or, possibly, comic politicians. The day goes on and I think, I really should post something--hey, maybe this!--and when I log on, there are diamonds and rubies scattered across the screen. I'm not going to put my paste jewel from the dimestore up there next to the stuff from Cartier.

Yet this--as astonishing as it is to see bright flashes of intelligence flare and die, replaced by the next burst of wondrous light--is but the simple use to which Facebook is put. It's like the smokescreen: it's what they want you to do, so that behind our backs, while we are diverting each other, they can be doing their . . . what? That's what I don't know; that's the unknown that scares me.

I know this must be going on, because I watched David Fincher's masterful The Social Network. I know because Mark Zuckerberg, the fellow who thought this up, is so scary-smart his mind is literally impossible to fathom. (Not that you'd want to, necessarily.) It was an idea conceived of in anger--and conceived of as purely transactional. A sales catalog of women: See which one you want today!

Because its intention was veiled from the beginning, it remains so, though the number of veils increase daily. We don't really know what they're doing with all the information they're collecting on us. And indeed, I suspect they don't yet know everything they're going to do with it in the future: but there are some very, very canny minds working on that at this exact moment.

What Facebook is good for, for any of us plebeians, is also multivalent, if less empire-building. It can be used to torture yourself, for example: you can troll around your ex, or your ex's friends, if she's blocked you or you've blocked her, and you can see who's doing what. With whom. Where. You can see evidence of parties you weren't invited to. You can see who's the most popular kid in high school: Four thousand friends? Who has four thousand friends? You can have done to you the coldest form of door-closing ever conceived: Defriending. It happens without a word. Slam.

It also shows who doesn't have a life, or at least doesn't in these cold winter days. That's most of us, apparently. The other night I found myself simultaneously engaged in three chats; I felt as if I'd just had a bunch of balls thrown at me with the command "Juggle!" Juggle I did.

You can't hide on Facebook. Or maybe you can, and I just haven't found the secret setting that would allow me to hide. To be a voyeur, without being spied myself. Even at that, though, I would still be watched. Bits of me, cell scrapings, taken without my knowledge. At some point, rest assured, it will all become clear. When we wake up one day and belong to someone else. Someone who is not our friend.

Published on January 29, 2011 06:02

January 22, 2011

Loving the One I'm With

Childhood leaves a memory-world intact but hiding, waiting for the trigger in the here and now. Then a sight suddenly unfurls before you; it seems touchable in its nearness, shining with the same impossible glory that made it worthy of storage all this time.

Childhood leaves a memory-world intact but hiding, waiting for the trigger in the here and now. Then a sight suddenly unfurls before you; it seems touchable in its nearness, shining with the same impossible glory that made it worthy of storage all this time. Such was a moment today, when Grandma's house at Christmas appeared suddenly in the air I walked into. I had set out for a post - ice storm hike on a favorite rail trail. I now faced a sparkly tunnel, an archway of ice-bedecked trees glittering darkly all the way to the vanishing point. That is when it was there, the baroque fairyland of sweets that made such an open-mouthed amazement of my grandmother's at the holiday. (This was the Greek grandmother, of course, not the Presbyterian one. The former believed life was just an excuse for elaborate presentations that perfumed the house with honey and nuts, oregano and garlic, butter and more butter. The latter believed food was a necessary nuisance, and if the succotash burned, it could still fulfill its purpose.) In particular, I remembered a pile of sugared grapes, refracting light into my astonished eyes. I did not even want to eat them. I wanted to stare at them, simply trying to understand how such things could exist. They looked permanent and fragile, at once.

Nelly was resolutely in the present. She ran ahead to greet the only other walker this day: a little brindle dog that appeared to be a cross between a Basenji and a small pit bull. Or something. (Ever notice how everyone who has a shelter dog doesn't have a mash-up of twelve or sixteen different breeds; their dog is an example of some extremely rare purebred, which of course it looks just like. Sort of.) The man on the other end of the leash called out, "What is your dog?" That meant he actually did have an extremely rare purebred.

"Crazy!" I replied.

"Mine is barkless."

"Ha-ho," I couldn't help but laugh. "Mine has enough bark for forty-three dogs. I wish I could give yours some of hers."

He just smiled. A little. Then he started briskly for the parking lot, explaining as he went that his dog really couldn't stand the cold, being originally from a subtropical country.

Nelly is from her own country. She can deal with just about anything--the cold, large dogs, small prey, cross-country skiers, bones as big as her head. She just can't deal with her own emotions. They are too big for her little soul, and they cause her to erupt in screams, piercing barks, screeching whines, and (when she greets someone she loves) a special concerto of cries that is indescribable. Except to say: it hurts.

People flinch; her voice has an edge that could take the five o'clock shadow right off your face. And I don't know how to stop it. Me, the amateur student of behavior. Me, the person who is supposed to be writing a book about the virtues of positive-reinforcement training.

Actually, Nelly is rock-hard proof of one of the basic principles I hope to illuminate: that behavior that is self-reinforcing--hey, it worked! The door opened; the boogie man went away; the food appeared; that made me feel better to get that out!--becomes entrenched. There is now effectively nothing I can do about it, unless I stopped everything else (tending to my child, working for a living) and devoted all my time to retraining her. After all the years I allowed her to train herself.

So she offers a peculiar situation: hating something she does, while loving all of her.

Because I do. I can't tell you why. Maybe because she's here. Maybe because she looks to me. And I have come to look to her. Just the old dance.

She, like anyone we chance to fall in love with, over time has shown herself to be one of a kind. This contains a lesson for me, and it is also has its weight, one as heavy as a cross to bear. I love her, which means I accept her. In the way I too would wish to be accepted: for all that I am. My flaws, you see, rather scream too, even if silently. After all these years, someone would also have a hell of a time retraining me.

We walked as far as we were able, each step in the iced-over and heavy snow requiring the effort of three in normal conditions. The vagaries of the day had to be accepted as well. Then we too turned, back through the sugary tunnel of time. Toward home, the place where we can be as we are. Nelly slept all the way, quiet, and quietly loved.

O seasons, O castles

What soul is without flaws?

--Arthur Rimbaud, "Happiness"

Published on January 22, 2011 05:14

January 14, 2011

Hit Send

It was the sort of room in which exactly this sort of conversation would take place: genteel, old, understated, and with an oriental rug underfoot. This was the site of a memorial art exhibition at the Pen and Brush Club, in a West Village brownstone, Edith Wharton territory. Therefore we murmured. We also held glasses of prosecco

and accepted Asian-fusion hors d'oeuvres off silver trays held by semi-invisible young waiters who wished they were anywhere but here. That is when I heard something that floored me.

I had been charged, by a relative, with collecting any inside dope I could about how to get into one of New York City's most exclusive private schools. At the kindergarten level.

I found myself talking to a woman whose three children attended said school. I tried not to think of the tab--over a hundred grand, I just learned from the website--in order to gather information diligently. A crucial item, she told me, was the letter one must write after the initial school tour. She helpfully listed some things the school might like to hear, then allowed, "Of course, some people hire a ghostwriter to do this."

You could have knocked me over with a feather--one dripping borrowed ink from its quill. Jesus Christ. Hire a ghostwriter to write a letter to a school for admission to kindergarten?

Apart from my broad and general naivete about how things are done now in this world (an unknowingness that extends, on one side, to the private grooming habits of young women these days [ouch] and, on the other, to the wow of learning that Lockheed-Martin apparently wields unprecedented power over every aspect of U.S. government; in both cases, who knew?), this showed me to be a positive rube.

Ghostwritten letters had gone out, or so I thought, with the prevalent illiteracy of the last century (the last before the last, I mean: the nineteenth). Then, people who needed that one persuasive phrase, the one that might turn a head most desired, would pay a professional to craft the letter of a lifetime. For those who did command the written word, but not the ability to gather enough flowers to make a suitable literary bouquet, there existed books of templates: the thank-you, the sympathy, the employment query. There are still those books today, although the handwritten letter--on paper! in an envelope!--is going the way of the floppy disk.

I have been blessed with some extraordinary correspondents, and not just in that antediluvian time of the postbox. In fact, e-mail has allowed some incredible prose to flourish; incredibly, it has been meant for my eye alone.

The only thing the e-mailed message cannot do is what I find among the letters, every one saved, sent me by my college roommate H. They are astonishingly well-written, first. They catalog events and feelings and people otherwise forgotten, second. (Without this record, which brings them momentarily back into the present--I see things before me as I hold the unfolded note, even twenty or thirty years later. Why, they must have lived inside this shoebox of letters, feeding on these words in the dark all this time.) But third, I saved them because they are unique works of art, made for me, with collages overlayed with rubber stamps, strips of colored paper torn and pasted just so, exquisitely Japanese in their sensibility. She wrote better than she spoke, and she spoke far better than most. Letter-writing is a craft and a discovery for the reader, temporally built, like a sculpture made of words.

As I said, though, now that I no longer receive letters in the mail (except from H. occasionally, bless her; they are beautiful as ever), I am yet not bereft of greatness arriving in the mail. Something arrives that knocks me back: brilliant writing. I can do nothing but attempt to reply in kind. We will go back and forth, and I find that the smarter, the more surprising, are the letters, the better are my responses, too. I never played tennis so well as when faced with an opponent who could cream me in the first three strokes.

I hope my backup program is doing what it is supposed to be doing, and I also hope that backups themselves aren't merely talismans of mystical hope. In other words, I hope to god these virtual letters are truly saved. Although they are private, I wish some could be made public, as some of my friends have written ideas, expressions, humorous riffs, tied together in a dense and perfect whole, one that rivals anything anyone ever set down in print. Perhaps they flew so high because what they wrote was not meant to be judged; yes, I think that must be so. It was meant to convey, as a boat carries its passengers, precious cargo, to the opposite shore. The beautiful sunset glinting off the waves was just something that happened along the way.

Sometimes writing a letter confers a singular closeness between two people, writer and reader. The considered missive has a different quality than the conversation, or the dashed-off message, or the query, or the phone call. It is meant to draw together two minds, two hearts. And it does, in the hands of the best letter writer. It is something that could never be ghostwritten. Only written, just to you.

I also find, when I look back in the

and accepted Asian-fusion hors d'oeuvres off silver trays held by semi-invisible young waiters who wished they were anywhere but here. That is when I heard something that floored me.

I had been charged, by a relative, with collecting any inside dope I could about how to get into one of New York City's most exclusive private schools. At the kindergarten level.

I found myself talking to a woman whose three children attended said school. I tried not to think of the tab--over a hundred grand, I just learned from the website--in order to gather information diligently. A crucial item, she told me, was the letter one must write after the initial school tour. She helpfully listed some things the school might like to hear, then allowed, "Of course, some people hire a ghostwriter to do this."

You could have knocked me over with a feather--one dripping borrowed ink from its quill. Jesus Christ. Hire a ghostwriter to write a letter to a school for admission to kindergarten?

Apart from my broad and general naivete about how things are done now in this world (an unknowingness that extends, on one side, to the private grooming habits of young women these days [ouch] and, on the other, to the wow of learning that Lockheed-Martin apparently wields unprecedented power over every aspect of U.S. government; in both cases, who knew?), this showed me to be a positive rube.

Ghostwritten letters had gone out, or so I thought, with the prevalent illiteracy of the last century (the last before the last, I mean: the nineteenth). Then, people who needed that one persuasive phrase, the one that might turn a head most desired, would pay a professional to craft the letter of a lifetime. For those who did command the written word, but not the ability to gather enough flowers to make a suitable literary bouquet, there existed books of templates: the thank-you, the sympathy, the employment query. There are still those books today, although the handwritten letter--on paper! in an envelope!--is going the way of the floppy disk.

I have been blessed with some extraordinary correspondents, and not just in that antediluvian time of the postbox. In fact, e-mail has allowed some incredible prose to flourish; incredibly, it has been meant for my eye alone.

The only thing the e-mailed message cannot do is what I find among the letters, every one saved, sent me by my college roommate H. They are astonishingly well-written, first. They catalog events and feelings and people otherwise forgotten, second. (Without this record, which brings them momentarily back into the present--I see things before me as I hold the unfolded note, even twenty or thirty years later. Why, they must have lived inside this shoebox of letters, feeding on these words in the dark all this time.) But third, I saved them because they are unique works of art, made for me, with collages overlayed with rubber stamps, strips of colored paper torn and pasted just so, exquisitely Japanese in their sensibility. She wrote better than she spoke, and she spoke far better than most. Letter-writing is a craft and a discovery for the reader, temporally built, like a sculpture made of words.

As I said, though, now that I no longer receive letters in the mail (except from H. occasionally, bless her; they are beautiful as ever), I am yet not bereft of greatness arriving in the mail. Something arrives that knocks me back: brilliant writing. I can do nothing but attempt to reply in kind. We will go back and forth, and I find that the smarter, the more surprising, are the letters, the better are my responses, too. I never played tennis so well as when faced with an opponent who could cream me in the first three strokes.

I hope my backup program is doing what it is supposed to be doing, and I also hope that backups themselves aren't merely talismans of mystical hope. In other words, I hope to god these virtual letters are truly saved. Although they are private, I wish some could be made public, as some of my friends have written ideas, expressions, humorous riffs, tied together in a dense and perfect whole, one that rivals anything anyone ever set down in print. Perhaps they flew so high because what they wrote was not meant to be judged; yes, I think that must be so. It was meant to convey, as a boat carries its passengers, precious cargo, to the opposite shore. The beautiful sunset glinting off the waves was just something that happened along the way.

Sometimes writing a letter confers a singular closeness between two people, writer and reader. The considered missive has a different quality than the conversation, or the dashed-off message, or the query, or the phone call. It is meant to draw together two minds, two hearts. And it does, in the hands of the best letter writer. It is something that could never be ghostwritten. Only written, just to you.

I also find, when I look back in the

Published on January 14, 2011 06:23

January 8, 2011

Bluish Blood

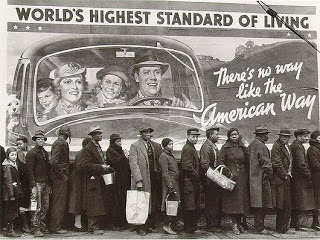

Margaret Bourke-White, 1937

Margaret Bourke-White, 1937Let us talk for a moment about privilege.

There is the type of privilege that is simply being here, now, alive. This is the highest. Then there is the privilege of, say, owning such an amazement a dishwasher, an appliance that accepts greasy dishes and spoons and returns them new again after the mere press of a button (and the selection of a crossword puzzle's worth of interlocking processes). It also returns a bill from Central Hudson, which I guess is also something of a privilege. I try to imagine what my grandmother, with a family of five boys coming out of the Depression, might have felt having such a thing in her kitchen--either a dead faint, or the Hallelujah Chorus.

I am hugely privileged, of course, and I know it. Not only in having a dishwasher, but also, in a short list, the following: a view out my window of rough and wild mountains (only partly ruined by high-tension wires, which I'd be a sorry ass to dislike, given their gifts [such as dishwasher and bill]; trade-offs are also a form of privilege); a car in my driveway that has not failed to start every single time I have turned the key; two motorcycles in the garage that do not always do the same, but this in its own way might be considered a privilege (that of needing to engage with them fully); the dog whose happiness redoubles my own when I watch her bound ahead of me on the trail with every cell in her being on fire with exuberance; the surpassing love I feel for her in the morning, whether it's come too soon or not, Miss Bright Eyes, complicated and uncomplicated both.

It goes without saying that the privilege of having a child, healthy and smart and funny, embarking on his own path into a world of peculiar privilege entirely his own, stands as king at the head of this nation of marvelous luck.

The final privilege I wish to enumerate, though, is a little more strange: the privilege of occasionally brushing up against august privilege--that of impossible wealth and luxury. And then retreating again, to my own life of advantage. Though everything is relative, isn't it.

I have been dressed in a long gown, ready to go to a black-tie gala where I will drink champagne and eat the kind of dessert that always features thin curtains of chocolate making a cityscape on the plate, and wondered if I had enough money to pay the cabbie to get there. (Riding the subway from Brooklyn in formalwear, especially high heels, is only for the heroically brave, and I am an abject coward, apparently.) I have been to homes where I was waited on by servants--I mean, the house staff. I have partied in a home that used to be an embassy, where the walls were filled with modernist artworks that would have been in a museum had they not been bought by an individual with more money than most museums. (Imagine entering a small private library, snooping about hopefully unnoticed, and discovering that it is the Joseph Cornell room. As in, not one, but many, of his incomparable boxes. I had to pick my own jaw up from the floor.) I have been to little fetes that cost more than I earn in a year.

Then I got back into my jeans and went, once a week, to the soup kitchen at Goddard Riverside. After ladling food onto the plates of people who had parked their shopping carts containing all their worldly goods in the foyer, people who shuffled by with heads down, lost inside the private universes constructed as protection from the intrusion of the outside in lieu of four walls, I would lead them in "activities." I had no expertise--crafty I am not--but in having the privilege of all that I did, I was qualified. I proposed teaching videography. One older man who never spoke, who never joined any other group, joined mine. After a few weeks, he smiled. For the first time that anyone there ever saw. A few more weeks, and I was told by a staffer that he said he looked forward to video class. Finally, it was just him and me. And then I had to leave. To rejoin my own life of privilege, I suppose. The pain I feel on visiting this memory, of having made him briefly happy, and then leaving him alone, is nearly scorching. Twenty years later, I can still see his face in my mind: his eyes, darting up, meeting mine at last. Then dropping down. Afraid, alone, gentle. Unknowing of privilege. I could cry.

I have a friend whose worth is in the double-digit millions. I have heard her complain of things she wanted to have. But, she maintained, she didn't have enough money.

My declarable income qualifies me for food stamps, but I do not need them. I am lucky enough to buy what I like at the grocery store, and I eat out in restaurants. When it is a particularly fine one, I order the appetizer. Half the prize, but more than enough. And gaze about me at the people who get whatever they want, and only eat a bit.

The greatest privilege of my privileged life is to have been able to walk the tightrope between two galaxies, and to pretend I am home in each. But I know I am not. I am only home in mine.

Published on January 08, 2011 05:25

January 1, 2011

Here Comes 2011

For a technophobe--not to mention an unusually negative and annoyingly stodgy person--I am loving, more and more, the immensities behind the black screen of my computer. They provide places to wander endlessly, and to sometimes find luscious prizes. You rarely go straight to them; instead, as in a great trip, you follow some road that gives a hint of promise or ask a local standing at the gas pump to suggest a sight, and thereby get to where you should go, but had no idea you were headed. It is also the process of love, where "one thing leads to another." Another is the best destination of all.

For a technophobe--not to mention an unusually negative and annoyingly stodgy person--I am loving, more and more, the immensities behind the black screen of my computer. They provide places to wander endlessly, and to sometimes find luscious prizes. You rarely go straight to them; instead, as in a great trip, you follow some road that gives a hint of promise or ask a local standing at the gas pump to suggest a sight, and thereby get to where you should go, but had no idea you were headed. It is also the process of love, where "one thing leads to another." Another is the best destination of all.So it was that I was led, through the long series of happenstance that is the internet's great contribution to life's possibilities, to something I haven't been able to stop thinking about. It is something small--infinitesimal, in all ways: a pop ditty, and not even a good example of the type, by the meagerly talented tween heartthrob Justin Bieber. But it had been made into something large, by someone who goes by the name of Shamantis. By applying a program (more unimaginable wizardry from the lands of technology beyond my ken, which is all of them) that slows and stretches sound by 800 percent, he has utterly transformed "U Smile" from the highly trivial to the deeply affecting.

Arbitrary transformations, accidental discoveries. There is not much more to ask for from life, is there?

That is what I wish for you, in the new year(s): strange finds, travels without maps, embrace of the unknown. And anything else that wants to come into your arms.

HAPPY NEW YEAR

Published on January 01, 2011 05:48

Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson's profile

- 19 followers

Melissa Holbrook Pierson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.