Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog, page 10

October 16, 2010

Kick

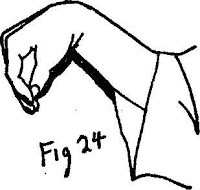

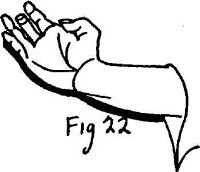

I am watching a room full of children finding that in life which we all search for: the sense of dancing, with tightly fixed control, along the edge of the uncontrollable. I am watching my son's karate class.

Eavesdropping, as is a parent's wont, on my kid's writing essay last week, I peeked inside his private life. "'Pack every punch with focus and with life,' my karate teacher says," he wrote, and this was galvanic: for it was a global truth. A generalizable truth. (On the way to the class, my child tells me I have "a big taste for small things," in response to my sudden laughter at his lovely turn of phrase after he'd asked me to tie the knot on his red belt: he could only make a "sad knot" himself. It's a beautiful image, one that could easily support a poem built atop it. It also yielded another pleased laugh at his big-truth appraisal of what moves his mommy.)

Now the teacher is saying, of a student who wears a perpetual mysterious smile: "I want to know his secret--I want to be like this guy." The teacher who teaches the children is in turn taught by them.

What the children do not know, but I do, is that their sensei has a reason that the smile, its inner impetus, eludes him. He has lost someone. I lost her, too, a friend. But he lost much more, when the young woman he loved left the world upon which she shined, in an eclipse that left us breathless in the dark.

He is looking thin and pale these days, even as he exhorts his students to "get into it, with spirit--that's more than half the battle. Every day, apply yourself to something. Your homework, doing the dishes, your sports, whatever. If you do something, really do it."

I am learning things here, too, watching and thinking, as the late-day full sun streams through the windows at this nice school. I am thinking about going home and applying myself to something that waits for me, something I need to hit as hard, with as much "ninja spirit," as my child just hit the practice pads (thump-thud). A fleeting thought intervenes--"I wish I had enough money to send him to this nice school"--and I realize that, indeed, if I truly applied myself (thump-thud) I probably could. I think of how I miss seeing my friend's child in this class, his happy, funny presence, because now that his mother is gone, he has had to go live far away. To leave us, and start anew. To hopefully apply himself to a new life.

Most of all, I am thinking about how desperately much I still need to learn about this time I have here, however much there is left. Part of this is how to move through loss with the grace of the karate master, with application and spirit and focus and humility. At this moment, in particular, I am thinking about how you get out from under an opponent who has got you on your back, with his full weight on you and your muscles quivering with the impossibility of it. I want to know how you make the impossible possible. I want, as the sensei now observes to the children, the feeling after battle that is "kind of losing control, but in control; kind of angry, but kind of peaceful." It's a strange feeling, he says. I am thinking I would like to feel it soon.

October 9, 2010

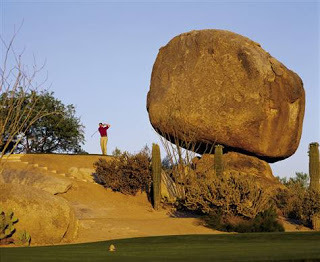

Golfing in the Desert

The earth owns itself.

The earth owns itself.What a strange concept, eh? It's very similar to the notion that An animal owns itself (the idea that PETA tries, in its regrettably bullheaded way, to get across--and an idea that is so logically, morally, and intellectually unimpeachable that the greatest difficulty I have now in life may well be trying to wrap my brain around how a single human, much less most of us, can hold beliefs like "animals are ours to wear" or "animals are ours to torture to death with chemicals" or "animals are ours to cage so we can look at them").

Add now to the list, though a bit farther down in immediacy, the difficulty in comprehending what's up with building golf courses, not to mention spas, luxury condos, and vast retirement communities, in the desert.

That bizarre concept--the voiceless earth has a right to speak--came into my mind as I was driving north in the Arizona desert recently (yes, in a car, with my closest relatives in it with me, only weeks after I had been in Arizona on a motorcycle, gloriously free of the compunction to order a Bellini at poolside). We were driving back to lie down and nurse the aftereffects of a grand dinner that included a bottle of champagne, and lobster--the latter not ordered by me, I'll have you know, since I also have a tough time getting the logic of putting a living creature into boiling water. It was the most lavish meal I'd had in years, in honor of my mother's eightieth birthday, and we were en route to the most lavish resort I've ever been in, an almost sickening spread of lush villas and a spa and, of course, the grotesque indulgence of golf greens made to grow from desert sand amid the saguaros.

Yet there are javelinas out there still, in the night . . .

(I longed to see one, but restrained myself from leaving tortilla chips out on the back patio so I might have a sighting. A fed wild animal is a dead wild animal. And I'm really, really sorry for feeding that chipmunk at the Grand Canyon, but he raised his hands in supplication and told me he was starving. Truly.)

"Someone bought this land, when it was boulders and space," my sister wonderingly said.

"Bought it from whom? Who 'owned' it?" I asked. Stolen from the Indians, who never dreamed of a thing called ownership. Strange concept, made up from whole cloth, I am beginning to suspect.

And that's when I thought it. The earth owns itself already, so it can't be owned by us. How then did the idea get flipped over on its back, so now it waves its four legs helplessly, scrabbling at the air? "We own it all." So that it, like all our animal brethren in the world, can be bought, sold, killed, or played golf upon.

Strange concepts indeed. I'm taking an aspirin and going to bed.

October 2, 2010

Falling

Walking through the fall woods, suddenly I make a realization: All squirrels have granite countertops. You think you are cool, stepping up to the de rigueur symbol of attainment in today's world? You secretly go into your kitchen in the middle of the night, don't you, and stroke that cold, shiny, black money with which you've lined the counters, don't you?

Walking through the fall woods, suddenly I make a realization: All squirrels have granite countertops. You think you are cool, stepping up to the de rigueur symbol of attainment in today's world? You secretly go into your kitchen in the middle of the night, don't you, and stroke that cold, shiny, black money with which you've lined the counters, don't you?I don't know if squirrel society has its yuppie class--"My work surface is bigger and flatter than yours"; "My tree is a Lexus, you Corolla-dwelling commoner"--but I see the evidence of their winter food preparation occurring all through the forest, on low, wide rocks. They have left the crumbled shells of acorns behind. They are getting ready.

Should I be getting ready, too? Oh, I forgot. I have ShopRite. Any week of the year, I can get bananas and strawberries (they blow, of course, but they look like strawberries). Maybe I should be getting, you know, psychologically ready.

For autumn is a little death. (Hardly as pleasant as the French variety; I don't feel like fully explaining the petite mort reference now, or especially why I thought to make it. Never mind, please.) It's the part where things die in preparation for rebirth; that old wheel, turning, turning. Reruns. Endless reruns on the TV of life. This is partly why some people get depressed around September. Others of us are remembering the gut-searing anxiety of the school year. Why? What was so damn terrifying about it?

Perhaps it only was for me. To tell you the honest truth, I don't know if I'm even reasonably normal, or if I'm like the kind of godawful psychological wreck that people can only talk about in private, it's that bad--and that irredeemable. There's no value in telling her . . . they think to themselves.

This is like going through life not knowing if you are a blonde or a brunette.

I guess I won't be finding out at this point. But it remains that I still do not know what I feared so deeply about the post-summer return to campus that to this day, decades later, gossamer butterflies still beat their ghost wings against my ribcage at the approach of fall.

And then--they cease. Or maybe migrate. I am no longer afraid, just eager. There is a use to be put for all of it: the shorter days (more work, more reading, more movies watched in bed); the cold (bracing walks, with Nelly bounding after squirrels, zinging with energy all of a sudden, coming to a dead-square unmoving of such magnitude she makes of herself a statue of watchfulness; then bounds away again, and I am filled with loving admiration of her skills, herself); the holidays (more excuses for prosecco). The negative curmudgeon in me deplores the smarmy, featherbrain's phrase, but fall and winter indeed make me think, Hey, it's all good! Fires in the fireplace, too: oh, yes.

The squirrels don't think it's all, or even a little, good. It's life and death. Edging closer to the latter every minute. Unaware, the heedless driver of a two-ton weapon runs over the mate busily helping put in stores for the lean time ahead--I have seen one half of a couple rush out in disbelief to investigate the corpse of the newly dead partner--and I have no problem (indeed, no particle of doubt) believing the survivor feels the sharp knife of grief, and hopelessness, and terror. And that she weeps.

Why should we have been singled out by evolution as the only animal to experience sadness, and to respond with the full range of emotion to it? It makes no sense whatsoever. And the biological world, if nothing else, is scrupulously logical.

Welcome fall. Fear it, only a bit. And drive exceedingly carefully, for the squirrels are en route to their luxuriously appointed kitchens. They have serious work to do.

September 25, 2010

Hooray for Poverty, and Riches

As we know, sometimes accidents are more educational, more salutary, than anything determined. Such was the case with the e-mail in-box last week.

I received the following message, in its entirety, from one of my dearest friends, a talented painter and ebullient soul:

It isn't all so bad, I know. I am living my dream really. I just want to be paid better.

Turns out she meant it to go to another friend, with whom she'd been having a discussion about how to manage the frustrations of a hopelessly busy family life while worrying about how to keep the finances upright.

I shot back my response, before I knew I needn't have. And I found myself saying something I had no idea I actually thought. But now I know I believe it, with all my heart.

No, it isn't. And in fact I'm beginning to realize that low pay IS the trade-off for living the life of one's dreams.

And I'm also starting to feel lucky that I do not in fact make a lot of money. It has a tendency to ruin lives.

Yes, we have it good, both of us. Beautiful children we love, the occasional laugh and hug, and cocktails.

No woman ever had more.

In Line, Lynn McCarty

September 18, 2010

Confubstprfion

There comes a time in every writer's life when she has to face the music. The name of the tune is "Deadline." Until then, she may sway to "Denial." But then the lights go down, the disco ball spins, and there's an insistent thumping through the floor.

There comes a time in every writer's life when she has to face the music. The name of the tune is "Deadline." Until then, she may sway to "Denial." But then the lights go down, the disco ball spins, and there's an insistent thumping through the floor.I had done much considering of what one might call my working method--an astronomer could discern nothing remotely methodical in it, and most of the time it does not work--but then I received a letter inquiring about how it was that I organized my thoughts over the course of a long work. It would seem the letter writer has the same challenges ("How do you return to your focus? . . . How does one return to a frame of mind that is familiar, or at least conducive to the ideas of the previous pages?") as I do, mentally. Poor sod.

I have been giving this some thought lately, finally, since I am in the midst of my rush to the end of my book (after waiting a year and a half, writing basically nothing). These days I fret endlessly about exactly the matters my correspondent has raised.

Focus?

I just hope and pray it will all turn out intelligible, or that a reader can at least connect the disparate dots. There is so much to say that my brain can probably be heard issuing sounds like a bowl of Sugar Pops when the milk is added.

Perhaps it is another form of denial, but here is my "working method" in a nutshell: I simply trust, in an almost religious sense, that since a single mind (barring the very real possibility of schizophrenia, I guess), then the myriad ideas are related to one another.

This is made harder by my incapability to write linearly. My ideas, to put it another way, are all over the freaking map, and I can't corral them any better than I could the fleas in a prairie dog town.

So, off in the distance, I see a hazy shape: the structure of the book. It is a stack, or a body. And not that I claim anything poetic for it--believe me--but the outline is conceived, when it is conceived at all, in exactly the same way that a poem comes to me. In a state of faith. In a state of external blindness. So that, I hope, I am in a state of internal seeing.

Or, in less mystical terms, I do what feels right at the moment. Out of the horrendous mess of all the notes and the snatches of longer bits I scrawl whenever the urge hits me (and it does so at the bizarrest times, like just after I've gotten out of the shower, or turned out the light, or walking with Nelly, or riding of course), I may reach for pieces written a year or two before. I had no idea then when or if they would ever be useful. And some of them never are. But amazingly, given the sad state of my memory, I can recall that they're there. Somewhere. Now, in which of the three notebooks, two file folders, and thirty-nine printouts, I couldn't begin to say. Just the looking can take an hour or two, and drive me crazy. I am highly unorganized, within this precisely organized mess.

"If you have any hints, tips, or the like that might possibly aid in keeping my stack of pages on track, they would be appreciated."

My dear D----! If only I could! But I sense that they are already quite unsteadily steady on track. You just do not know it yet, or trust yourself that they are. There is in fact some internal librarian in your mind, scuttling about and ordering thoughts according to the Dewey Decimal System.

Of this I am sure. It is just that librarians are very quiet. It is their profession. And fearfully doubting that we can pull it off: as writers, you and me, that is ours.

September 11, 2010

Ride: to Eat

The motel nights punctuated the days: the period at the end of the sentence. The next day, a new sentence to write. At last, they strung together in a long prose poem, The Big Trip. The meaning was not known until the end. And the end has not yet been arrived at, since big trips have an endless coda--memories. They recur at strange moments, disconnected sensations bubbling up from somewhere unseen. The sun slanting across the Napa grapescape. Garberville ("The Hemp Connection"; the Sherwood Forest Motel). And, like the commas and semicolons in the middle of those sentences, meals.

The motel nights punctuated the days: the period at the end of the sentence. The next day, a new sentence to write. At last, they strung together in a long prose poem, The Big Trip. The meaning was not known until the end. And the end has not yet been arrived at, since big trips have an endless coda--memories. They recur at strange moments, disconnected sensations bubbling up from somewhere unseen. The sun slanting across the Napa grapescape. Garberville ("The Hemp Connection"; the Sherwood Forest Motel). And, like the commas and semicolons in the middle of those sentences, meals.Outside Yosemite, at the Best Western, the Spaniards swum darkly in the pool; the French spoke in low tones to one another. The Germans asked politely, and formally, in near-perfect English for directions at the front desk. And at the "breakfast buffet" the next morning, I cringed: So this is American cuisine, they thought to themselves. Cheerios, white bread soft as paste, gluey margarine, "coffee," gelatinous jam inseparable from its plastic pack.

This is largely how I, too, ate for a month. The high end was Outback Steakhouse; the low end was . . . low indeed. Much trail mix passed through the digestive system, many cheese crackers. In the hellish heat of Kansas, of Nevada, orange dye mixed with chemical electrolytes washed into the bloodstream. A pack of peanuts, ice cream, French fries. More French fries.

In San Francisco, we wandered through the farmer's market at the Ferry Building, and my craven sighs were audible. Not just organic peaches, by the cartload, but nine types of organic peaches. A great spillage of colorful produce. And none of it would last a half hour in a tank bag. So we wandered some more (twelve dollar malted milk balls?), fresh fruit juice from our single taste dripping from our fingers, and then turned to walk back to the shop: the bikes were ready, wearing fresh rubber, and we needed to ride again.

There is a kind of riding where meals are simply a kind of fuel to burn, and procured at exactly the same place as the bike gets its gas. Or maybe from the saddlebag, where you've stashed the granola bars you bought at Target way back when. I had food that had seen hard miles, crushed beneath the electric jacket and the laundry bag, from New York to California and now back to Colorado, where their crumbs perform a utilitarian function at last, when I was hungry enough not to care. Much.

The motel rooms were our temporary home. (What is it with the astonishing proliferation of chain hotels in America? I must remember to update my drugstore rant; there's something up with the economics of so many, many imposingly large, anonymous structures, with their expensive rooms and, yes, identical [and identically bad] breakfast buffets). For maybe ten hours. A quick swim. Then to dinner at the nearest option, usually scoped out while still on the exit ramp. Applebee's, IHOP. There was real food out there, but it required getting back in gear. Sometimes you just want to walk, you know? So, next to the chain hotel, surprise, there is the chain restaurant.

This is America. But that is also America, too, and we saw it all: the miles, the miles, the miles. The variegated. The old, the places they have not touched. The Cowboy Cafe nearly made me laugh, its perfection. The dust in the air, across the empty crossroads.

We saw it all. Or what we passed, which felt like all.

For the record, the pies at the Thunderbird Restaurant were delicious. And if they were in fact ho-made, well, I think everyone deserves a pleasant way to spend their downtime.

September 6, 2010

On Return

Returning is itself like embarking on another journey: inserting yourself back into this newly strange thing called your "life"--as if that wasn't!--becoming "yourself" again--but who might that be?

Returning is itself like embarking on another journey: inserting yourself back into this newly strange thing called your "life"--as if that wasn't!--becoming "yourself" again--but who might that be? I have much unpacking to do. From my luggage. And from my mind.

But then: Welcome back.

August 28, 2010

Time Like a Bridge

I was a different rider now. I moved back and forth between two worlds, mommy world and motorcycle world. They had different people in them, different priorities, different codes and language. Citizens of these countries on the other side of the globe from each other couldn't understand why I didn't fully inhabit one or the other, and I could not explain. Did I want a unified life? No, I just wanted time to be endless so I could continually slip through the crack between the two people I was. I wanted all the time in the world to put on a dress and go to friends' for dinner, drinking wine on the patio and discussing the current presidential administration while the children played in the backyard. I wanted all the time in the world to go motorcycle camping and ride to Florida and talk merits of tires and spend whole days taking pieces off engines and cleaning them and putting them back.

I did not have all the time in the world. All at once, I knew. Time had become rare, elusive, choked off and breathing hard. While I was going on my way, I had unwittingly made a passage of some moment.

There is a time like a bridge—let us say it is the age of fifty. On one side of the bridge is forever: no idea of "end" intrudes on anything, especially one's daydreams. Tell the fortysomethings, then: Go, have your big parties with your big platters in your big houses. Sometime soon, it will all seem too big, too full of infinite hope; a little pointless. Life's vista has narrowed. That is when you have crossed over the bridge, and that is when you find yourself thinking alarming things like, Holy shit, I may, if I am lucky, have something like twenty-five, maybe thirty, years left. And I'm not going to be riding into my seventies, probably: some people do, but perhaps they shouldn't. Enough said. So—fifteen years left. That means fifteen seasons, those ever-shorter leases on fine weather that blaze by and melt into cold.

August 21, 2010

This Is the Iron Butt Rally

In 2009, some thousand riders vied for a hundred spots, which were determined by lottery, and also by fiat of the emperor, who can make as many exceptions as he likes. This is to ensure "color," in the tint of bikes like the two vintage RE5 rotary engine Suzukis from the seventies that were considered Hopeless Class entrants. They were also ones, a quarter of a century later, that gave a reverent nod to rally history. That is because George Egloff was mounted on an RE5 when he rode to one of the first place finishes in the original "Ironbutt" in '84. Their inclusion was the equivalent of placing a george washington slept here plaque on some old stone house; historical markers signify less the commemoration of a place than the legitimation of an institution. The Iron Butt Rally was now officially a Big Event, wrapped in a corporate identity replete with sharp-minded legal counsel, an international following, two solid pages on trademarks and the association that go out to each person who becomes a member, and the voluminous storytelling—from multipart ride reports posted on blogs and forums to the official word of the organization in its daily reports during the rally and the articles in its new glossy magazine for "premier" members—that form Old and New testaments of long-distance riding's Bible.

Besides, the underdog is an irresistible category in American self-conception. Motorcyclists may be disproportionately drawn to expressing humor of a dark sort; they are certainly fond of testing themselves, as witness the entire long-distance enterprise, and so they are driven again and again to prove that Hopeless is sometimes not so hopeless after all, provided the rider on the underpowered machine has the guts to make up for the lack of displacement. The two smallest bikes ever to survive the crucifixion that is the rally are 125s, Suzuki and Cagiva. The 2001 Hopeless Class was especially lively, with Paul Pelland finishing on a 2001 Russian-made Ural (which might as well have been a 1944 Ural) and, more heroically, a 1946 Indian Chief piloted by Leonard Aron making it all the way to the final checkpoint. In 2003, Leon Begeman came in twelfth on an EX250 Ninja that was actually the resurrected ghost of seven previously expired Ninjas. If kites were allowed in the Iron Butt Rally, someone would find a way to fireproof lightweight nylon and fit a four-valve engine to a balsa-wood frame. Then fly seven feet above the ground for eleven days, finally to crack jokes at the finishers banquet while being good-naturedly jeered for stealing a top-ten place from someone who really deserved it.

Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson's profile

- 19 followers