Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog, page 3

February 11, 2012

Caught

Mice are on my mind, because they have been on my counters.

Mice are on my mind, because they have been on my counters.I am not alone in feeling that I am in a battle to the death with these small gray denizens of the night, but I prefer if the death go on outside my view. Therefore, I employ traps that allow me to "humanely" catch and release them. I am under no illusions as to what happens to them after I do: mice reproduce at an astonishing rate (in seven months, a happily wed couple may be responsible for bringing over two thousand little beings into this world) because they have to, living at the bottom of the food chain as they do, and being relatively fragile in relation to the giant species that surround them. Still, I'd like to give them a chance. A chance to live elsewhere. Not here.

They have a fine nose for the ideal meal. The unripe bananas go untouched. When they reach the perfect state of yellow, however, gently flecked with brown, then they are ready, and I am likely to find a repulsive mess of scored and gouged fruit, surrounded by the post-digestion effects of that meal.

So I lose some bananas. And bait more traps. But it is what is in the garage that is a more threatening meal, or rather, chewable nesting material: the wires of my vehicles. Every winter the motorcycle forums are filled with long threads about how to repel mice from the airbox, which seems to be a favorite spot to nest (and who can blame them? A dark and quiet hotel room, just perfect for Valentine's Day trysts!). That nest is likely to be softly lined with the shreds of former electrical components. Nothing you want to discover on the first warm day of spring.

After festooning moth balls, tied stylishly in plus-size stockings procured from the dollar store, throughout the engines for the past couple of years, this year I tried something new, just for the sake of it: dryer sheets. Not the Free & Clear kind, either: the toxically perfumed ones. I don't know how anyone can use these on their clothes, in the house, without asphyxiating. Surely, then, these would do the repellent trick!

Stuffed in every crevice and opening, they make motorcycles look like they're fresh from the French cleaners, hung on paper-covered wire hangers and enlivened with tissue paper wads to prevent wrinkling. I even added them to the new Honda generator, because I would have to take the bus all the way to New York City to find a tall building from which to throw myself if this absurdly expensive addition to the garage were ruined after only two runnings. However, the protective stuffing takes some getting used to, as I discovered the first night I was called upon to fire it up. It was four a.m. in the middle of a windy, icy rain storm. After putting my boots on, grabbing a flashlight, and donning the ski jacket to run outside, drag the generator to the front of the garage (not easy, as it is a hefty devil), then race back down to the basement and six inches of water to punch out the window, run the extension cord from the garage, and plug in the pump, I was running with adrenaline myself. At five, back in bed once more, I wondered how I was ever going to get to sleep again. A half hour later, I had willed myself into a state of calm, doing some slow breathing exercises and starting to count sheep--or mice. Oh, jeez! The dryer sheets! Back I went, out into the whirling black cold.

The next time, though, the dryer sheets were the first thing I remembered. You can be sure.

When I was a girl, my friend Laura and I kept mice as pets. One was called Trubloff, as in "The Mouse Who Wanted to Play the Balalaika." (Her family also had a calico cat named Mnlop, as in the contiguous letters of the alphabet, and pronounced Menelope, which to me always sounded like one of the missing Muses.) The thing was, these mice kept eating their babies. This was rather disturbing to two little kids. What we didn't know then, but I do now, is that this was the result of living in captivity. It was a very nice glass cage, mind you, but it was still a cage. Later I came to realize that access to the social and physical systems in which a species evolved is a birthright. Rights can never be conferred. They can only be taken away. And that is what has been done to every gerbil, hamster, rabbit, songbird, or human who is put in a cage, whether it is made of iron bars, tyranny, or wire from a pet shop.

I wake up sometimes at night, wondering what defenses I, a claustrophobe, could muster against solitary confinement in a small cell. The panic uprising. None, I decide. I would eat my young.

An animal rights group has recently brought suit against Sea World, on the grounds that their orcas are subject to slavery. The verdict may be arrived at quite simply: open the pools to the wide sea. If the killer whales swim out into the dancing waters of freedom, we have the answer.

The other morning, there was a mouse in the trap, trying to hide itself in the corner. I knew I would not be able to leave the house and drive it away to release--at least three miles away and preferably on the other side of a body of wate-- until later in the afternoon. I pulled from the cabinet a tiny cup I had bought at Ikea some time ago for its lovely mustard color and amusing bowl shape. I had never found a use for it, but now I saw that it was a water bowl for mice. I gingerly opened the lid to put it in, knowing that I might risk a gray flash and the loss of the mouse, forever, to the land under the stove. Mice, like all of us, are powerful learners. Give them liberty, or give them death. Every time I open the door of their cell, I sincerely hope it is, for them, not both.

February 4, 2012

We Were Devo

Times have changed. Everything has changed.

Times have changed. Everything has changed.Well, maybe not the fact that it is the nature of all things to change; but everything else. Take Devo, for example.

It was probably 1975 when a few of us convicts, er, boarding students escaped campus one night. This was verboten. Boarding students were to stay on campus, in dorms or the library, and we had a curfew. But we also had day students, who had access to cars, and those cars had floors, which were convenient for hiding boarding students until the edge of town. Furthermore, we had Kent to lure us away . . . a university town, which like Oz rose majestic in our imaginations with glittering promises. Those were called bars. With beer, and music, and everything.

Sometimes the school deployed professors to go hang out in Kent's bars to catch us--probably not a bad Friday-night assignment--but this one seemed devoid of official presence. What it did have was a band, announced with a silk-screened poster taped to the door, that none of us had ever heard of. No matter. We were going to hear, plenty.

They began the show with screenings of some grainy 16mm movies of the type once called "experimental." The experiment in this case succeeded, brilliantly. I was stunned by what I saw, like nothing I'd seen before. I knew I had just walked to the brink of a great canyon, with a breathtaking view of the future.

The band followed the promise of its short movies. Together they were sarcastic, nutty, mordant, and finally really, really smart--exactly what I liked, even if I didn't know it quite yet. (Perhaps because both bands were started by art students, and this touched their music, their gestalt, in similar ways, I would have similar feelings when I heard, on my college radio station, a song called "Psycho Killer." Instantly I knew I would never be the same again. I wrote my senior thesis to endless spinnings of Talking Heads 77, which might have had something to do with the way it turned out.) After the show I went up to the one or two Devotees to babble incoherently, though I was trying to say how I had seen something new that shook me from top to bottom, and thanks for that. I did mention my belief that they should get out of Kent--they were obviously too big for Ohio--and go to New York City. "We're thinking of doing just that," one of them said. (A couple of months later I saw Devo perform in the basement of the Akron Art Institute, where they confused the audience into near silence; these were not college-town bar patrons for sure.)

As I left the bar, I ripped the poster off the door.

There is a recent interview, here, with band member Jerry Casale in which he sounds depressed and bitter, as well he might. He describes a situation that is little remarked on: it is not just "the" middle class that has vanished in the United States; it is also the creative middle class that has been squeezed into nonexistence, between a vast population of working artists who can no longer hope to make a cent and the 1 percent that will make killing in the corporate marketplace and get covered by Entertainment Weekly. Musicians have nothing to sell anymore; when Barnes & Noble closes, following the final disappearance of most independent bookstores, authors will

join the ranks of the newly unpaid "content providers," which has become the fate of most other writers who used to be able to cobble together a living writing for print.

I found the Devo poster in my closet when I was cleaning out my childhood home a few years ago. Unearthing it from where it had lain under the bed for decades was like finding a priceless artifact from an ancient civilization. I put it away somewhere, and am counting on finding it again sometime. Hopefully soon.

January 28, 2012

Lineage

Tonight, I drive through a town with no name and no place, because it is every place. It is just as well not to name it, because naming things corrals them, and sometimes you want them just to leak all over the page, saturating every memory with the same ink to bring them together in the blue wash. To assure yourself you are still the same: The past is not in a different zone, latitudes away from where your eye lands just now. Your past and the people who made it are here right now.

Tonight, I drive through a town with no name and no place, because it is every place. It is just as well not to name it, because naming things corrals them, and sometimes you want them just to leak all over the page, saturating every memory with the same ink to bring them together in the blue wash. To assure yourself you are still the same: The past is not in a different zone, latitudes away from where your eye lands just now. Your past and the people who made it are here right now.Old buildings carry with them accreted emotional layers, air-dried, of the people who lived in them, one on top of the other. Why do they read as predominantly sad? Why is most life, when over, an encrustation of sufferings? I feel it as soon as I look at it: unhappiness, crushed hope, years collapsed too soon. With a sprinkling of efferverscent moments, joy and the spring of luck and hands caressing skin. That happened in these walls, too.

The redbrick building I pass slowly was built the same time as the one I suddenly recall: in the twenties. At the exact same time that I am in an old Subaru that sometimes makes strange noises, I am inside the building that glides by (a light turns yellow up ahead). That is because I am now in Akron, my hometown (you can be in yours, too, crossing miles and years in a brilliant flash), in the dark interiors of the Twin Oaks Apartments. They were across the Portage Path--itself a road into the past, that of the long-disappeared original peoples who had worn it down to hard-pack under their stolid, moccasined feet--from the Portage Country Club. I daresay no one who lived at Twin Oaks belonged to the country club. My grandmother lived there.

Sometimes we fall. Sometimes we have something we think we will keep forever, and then we lose it. We fall downward.

That is the story of life, and its inevitable tragedy: not the loss, but the belief that in the end excoriates--that we will never experience it. Sure! We will have into old age what we have now--oh, and also that there is no such thing as old age. That which is nothing but a final series of losses.

The front door to her apartment was never used; the way was blocked by a huge dining table wedged into the hallway. It belonged to that past she never believed would leave her, either: the stately Tudor house in the town's best neighborhood, into which she and her husband had clawed their way from the decks of the ship that arrived from Greece to the shores of new hope. Uneducated, but driven--I am educated, but undriven, which may be the true tragedy hidden in the immigrant's story--they worked, each at their trade. My grandfather's was (need you ask) restaurants. The first, the Roxy Cafe, in downtown Akron held great promise. The town was gripped by rubber fever: the newly populist automobile had put every hand to work making tires, and still the workers poured in. The only similar jobs boom one could experience now would be in China, and it might be as pleasant: the work was long, hard, dark, and smelly. But it was work, jobs by the thousand.

There was only one thing wrong with the Roxy Cafe, and it was not its phalanxes of white-draped tables and bentwood chairs arrayed with military precision, its gilt-painted walls and dark-wood booths and neat checkerboard tile floor. It was that it was opened on the eve of the Great Depression.

But he bounced back: there was no choice for a Greek. There would come a time for more restaurants, each more impressive than the last, until the late fifties, and another boom, this time supporting the Continental pretensions of a downtown establishment bearing the name The Beefeater. Thus was a wish attained: the final expunging of any taint of the truly foreign. The way had been made clear, before this, by the gentle twisting of the odd otherness of the family name, Roussinos, into something more palatable: Russell.

My grandmother's work was similar: to study, closely, the customs and manners of the native-born and emulate them. Thus the woman with the grade-school education learned where to send her children to college (cleansed and white bastions of the highest reputation), what clothes to wear (anything from the pages of Vogue, bought on trips to the department stores with velvet-covered banquets in their inner sanctums of couture, where the salesladies knew her name), what to prepare for dinner (House & Garden was the Bible here). The meals were six courses, and though they sometimes contained the best of Greek cuisine--garlic-studded legs of lamb, homemade kourabides, taramasalata--they also reveled in ice cream bombes and ornate hors d'oeuvres bristling with toothpicks.

They were consummate students of the American way, Gatsbyesque. And then, they fell. Perhaps it was my grandfather's habit, American-hopeful, of buying stocks on margin. Maybe it was simply the trajectory of many a life. Downsized. The furniture, most of it, went. Sold, dispersed. I have the canopy bed of their youngest child. My sister has the olive-velvet settees from the living room; my other sister has the wicker screened-in porch furniture. Their dining table, seats for twelve, followed them to the three-room apartment at Twin Oaks. It never fit.

My grandfather died, as grandfathers do. My grandmother lived on, never sure again what she was living for. The small apartment depressed her. It depressed me. The kitchen was so small. She slept in a twin bed. The place still reminded me of him. She bought a lottery ticket every week. She still hoped to pull herself back up, and out of there, Twin Oaks.

She called us often. Get me out of here. I'm lonely. She had never learned to drive. She was a prisoner of the Twin Oaks Apartments. And this is what I felt when I drove by its doppelganger, far away but as close as the mind will sometimes allow. The sense of falling, falling, backward. Into time. Into the past, or into the future, all of a sudden, mine.

January 21, 2012

The Play's the Thing

Malvolio. "Be not afraid of greatness": 'twas well writ.

Olivia. What mean'st thou by that, Malvolio?

Malvolio. "Some are born great"--

Olivia. Ha?

Malvolio. "Some achieve greatness"--

Olivia. What say'st thou?

Malvolio. "And some have greatness thrust upon them."

Olivia. Heaven restore thee!

Malvolio. "Remember who commended thy yellow stockings"--

Olivia. Thy yellow stockings?

Malvolio. "And wish'd to see thee cross-garter'd."

Olivia. Cross-garter'd?

Malvolio. "Go to, thou art made, if thou desir'st to be so"--

Olivia. Am I made?

Malvolio. "If not, let me see thee a servant still."

Olivia. Why, this is very midsummer madness.

--Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

Outside, the early dark falls in a freezing rain. The fire indoors is necessary, and I pull as close to it as I can without lighting my sweater as a flare. And then I reach for one of the free calendars saved from the mail (World Wildlife Fund, Humane Society, Defenders of All-That-Was-Once-Natural-and-Soon-Is-to-Be-No-More) and begin charting summer.

Not my summer--that still exists to me only as hopeful scrawls over June and July weekends of the motorcycle rallies I want to attend and may never get to--but my child's. It is so complex, and must be mapped so far in advance, that I need a separate flowchart for it. God help me if I schedule Farm Camp for the best week of Wayfinders, or town camp when Seewackamano is full of his friends. All heaven help me! This is my midsummer madness, in the frozen heart of winter.

The centerpiece of the summer camp lineup, and possibly of our whole life up here in the boondocks, is Shakespeare camp. For years now, we have been in thrall to a periodic transport of magic: the child's production of plays over four hundred years old, written countless galaxies from the iWorld that is all these children really know. Together, on an outdoor stage in the Catskills dubbed The Little Globe, they offer up the truest proof that great literature can live, its meaning as immutable as granite, forever.

For two weeks, the actors immerse themselves in old English, in characters and rituals and historic detail that is as foreign to them as the back side of the moon. My son bounds out of the car every morning with his lunchbox and disappears into sixteenth-century England. And then, one humid summer evening, we convene.

The fanfare sends its gathering notes over the mountain pines. Parents wait, motionless, on bench and blanket. Then the costumed children--six years old, ten, fifteen--emerge from the woods behind the stage, or file down the aisles. The play begins, their small voices now big with immortal poetry. They do not recite the lines; they live them, for they comprehend. They know who they are, completely and down to the bone: Puck, Orlando, Beatrice.

In another week, the muslin shirts and embroidered bodices will again hang silent in the director's home, waiting for another summer to begin, and my son will be splashing in a pool, or riding bicycles with friends, or making animations on a laptop. But because of a small miracle that is actually quite large (this is here, by chance and by the Ashokan), a boy has learned that two weeks can be marked on a calendar. They can also be timeless.

January 14, 2012

Wonderfulest

With a little patience and a lot of paper, I could map out every great thing in my life. I would discover, when I studied it, they are all to be found at the junction of other people and chance. Where these two roads meet, wonderful things appear.

With a little patience and a lot of paper, I could map out every great thing in my life. I would discover, when I studied it, they are all to be found at the junction of other people and chance. Where these two roads meet, wonderful things appear.Riding a motorcycle takes you to that corner faster than any other way. Motorcycle riders are a source of the same endless surprise that their rides offer them--open to serendipity and to what happens: to the great Come What May.

Through a chance meeting (and is there any other kind?), one rider has lately become a friend: closer and closer, bit by bit. Funny and magnanimous and generous, he is willing to share his friends in turn. And so, one night a while ago, I found myself at a table of people new to me, and the possibilities they represented were spread out like a feast. As in fact a feast was on the table in front of us; it's a very good restaurant. But some possibilities are tastier than others. Midway through the meal, I asked the man next to me--talking to whom proved a bit like getting rocks out of a mountainside garden--if he wouldn't mind changing seats. That is because there was something about the woman on the other side of him. Our mutual friend had had the idea we might get along. He is perspicacious that way.

A few rare times in a life, we are given what we need at the precise moment we can use it most. A person appears whose words, ideas, spark and burn.

They reveal themselves slowly, though, in their ideal purpose as catalysts of furtherance: that is in fact how you know it was "meant" to be. Because you had no idea, at first. No idea that a friend can help show the way with such a bright light, or even that the way had been so dark before. Not to mention how much fun it is to talk about the things that matter most to one, when they are also the things that matter most to the other.

I was told at first only that she was an artist. OK, an artist. There are millions of those. But a real one, one of the true uncommon, and one who just happens to have a studio in the factory building next door, the roofline of which you can see through the winter-bared trees out your kitchen window?

This was beginning to feel eerie. And then I walked into her studio, and gasped. Emily Dickinson, herself one of the rarest of the rare--the true artist--said she knew something was poetry "if I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off." I felt my skull rising skyward as I saw the beautifully strange works hanging there. And then I caught sight of the small office space off to one side of the studio.

The walls were papered with show ribbons, a solid quilt of blue and red. Her dogs. Agility champs. Turns out she is also a dog trainer, and she knows more about positive reinforcement training than any nonprofessional I've ever met. This--the artist, to bring me back to what had fed me for a long time in a past life, and the dog training theorist, to bring me back to a project long stalled and now barking to get free again--feels like I've stepped into a moment of preordination. By way of a very nice dinner, a friend who knows more than he knows, and the lines converging on a map.

Let's go now.

January 7, 2012

Apocalypse Then

It's an arbitrary construct, the "new year." It gives us false hope—which becomes real—of rebirth. Yet it is of course made of pieces of the real, the revolution of this planet we are on, its revolutions around a solar system in turn. We can't get off even if we want to! Instead, we can leave it only by being buried a few feet into it.

Think about that for a moment.

I am doing so right now, as I sit by the fire, with R.E.M., a dead band, revolving on the turntable. It all goes around and around, the years and the records both. Music is just a construct too, but made of real bits of mathematics and resonances and neurology. Perhaps it could never not have been conceived. It is that much a part of who we are. I feel that way about movies. I feel I can never see enough. I feel that we were just waiting all our history for 1895 and the coming of the movie.

On Christmas Day, we sat in three seats in the second row, a crappy vantage in any theater. But it was opening day, and across the land, those of us unmoored from a family feast were looking forward to being transported by an epic vision, followed by the requisite Chinese food (or, in our cases, Indian). This is what is known as "Jewish Christmas."The boy has long been wondering, in his preternaturally smart way that frequently dumbfounds me, why World War I is relatively infrequently considered. After a little thought and a little reading, we discussed the probability that such unspeakable destruction, based on a lie that then gave rise to another horrific multinational bloodletting, was simply too hard to look in the face. Better to bury it, and hope it does not rise again. But of course it does; the world turns always anew in revolutions of willful forgetfulness.

After the happy chocolates in the stocking and the strewn wrapping paper and ribbons of youthful fiction—Santa came!—I strongly suspected that a movie scheduled to open wide on December 25, even if based on that unfathomable episode, would not partake too much of truth: nothing won; so much promise, contorted in frozen pain in the mud. No, in the malls of America, one must be certain of a happy end. Certainly there would be moments of fear, but they would be quickly relieved in a spreading pool of corn syrup, our national food. Children's movies now permit death to come to only peripheral characters in whom we have invested ten minutes or less. I knew thus at least one War Horse would survive. Even if none of his real-life counterparts ever did. Over eight million horses died in varying levels of agony in the war. Those that managed to survive got a trip to the slaughterhouse as a medal.

What has happened to Steven Spielberg? Has he completely given up? On the evidence of this movie, apparently it is he who has laid down and died. There is no heart even in his conventions, of which "War Horse" is a cryonically sealed package full. There is not an original moment, or a true and human word, in the full 146 minutes. Yet there is a performance of toweringly noble proportions, though the actor speaks no line. The horse, with four white socks and a white star, says in his silent appraisal of this foolish world of men all that could possibly be said.

Otherwise, two scenes, and two scenes only, rouse the viewer. The tracking shot of the first cavalry charge, through the wheatfield, is a moment that widescreen film is made for (only a construct,--but also all that we can make of this inscrutable life). The movement, the rhythm of the editing, the vantage given to us even in the second row, work simultaneously on eye, brain, and heart, and it is thrilling, as it must always be when the recipe's measurements are followed precisely. Yet it leads necessarily, given the particular plodding mission Spielberg has set himself, to pedantry: in the next moment, we are lectured on historical fact. Cavalry is retroactively rendered anachronistic by machine guns. They do not belong in the same place at the same time. War is an awful place to discover the mistake.

The second time the emotions rise, though duly bidden by cinematic manipulation that feels awfully familiar, is when the horse is in danger. In terrible, potent danger. The type that an actual horse could never survive for a fraction of this time, not enough to wind us into the frenzy of sickening dismay that a fictionally extended run through razor wire does. I longed for the larger shoulder in which to bury my face. Instead, I used my own coat. And when I looked again, he was there, bowed but unbroken (and barely bleeding!), ready for his own Christmas Truce made by wire cutters.

As I had suspected, our appetite for samosas was undiminished by the ending, a happy reunion and the promise of endless fields of emerald green. Not that I wanted to cry. But then, I do. When I go into the dark theater, I want to feel something, life and its awful beauties compressed like poetry, by the revolution of the spools and what is made by a simple turn.

December 31, 2011

Swimming to Reality

When I first get in, it's a shock. It's cold, and I think, What am I doing? And then I begin to swim.

When I first get in, it's a shock. It's cold, and I think, What am I doing? And then I begin to swim.A hundred yards of freestyle. A hundred yards of breaststroke (aka reststroke). Fifty yards of freestyle kick. Then another round of all. At the end, fifty yards of freestyle, as fast as I can go. It erases everything in my brain, except for the thought: You can do it. You can do anything, as long as you know there is an end, eventually. Then I see it, under the moving blue, the line that tells me there are just two more revolutions of the arms. Finally, I touch the wall.

Actually, I hit the wall before I in fact hit the wall. At some point, there will be the place where swimming and thought merge. Where skin and outside temperature have no boundary. Then, there is realization.

Last week at the Y, I realized something that had been there all along, something that had underlay my entire life up to that point. There are things we think that are as the concrete foundation under the house, unseen but holding it up nonetheless. As usual, the sudden realization hit me in a fully formed sentence, words to an assumption that had never been spoken, all these years. If only I had been born with a perfect body, I would find someone to love.

I almost laughed underwater (not a good idea in a public pool) at the absurd idea. A perfect example of magical thinking. But yet it is what I believed. All my troubles, all my life, in fearing that I might never find the perfect union, had been about my imperfect genetics. If only I had been one of those women with lithe and shapely legs, there never would have been any of that heartache. There never would have been those years of dearth, those thousands of nights alone in city apartments, wondering if there was anyone, ever, who would lie beside me, take my hand, say the simple words I thought would mean the end of loneliness.

Now I know that wasn't the problem. Or perhaps it just complicated the problem for me. Because, according to the cover story in this month's The Atlantic, the problem is men. Or rather, economics, imbalanced numbers, and the freefall that ensues.

The author of the piece is pictured on the cover, as if to prove a point: She's very attractive. And she's obviously smart. She just didn't quite know what she was dealing with. So she's alone now, on the sharp edge of forty.

She was attracted to the same sort that I was at her age: the dark artist. The poet, or the painter. The kind who goes out with you for six months, then announces: Uh, not yet. I'm not ready.

Turns out they're never ready, until they're fifty-five or so, at which point they're ready . . . for a thirty-five-year-old. So they get it all--decades of banging scores of beautiful women (see, here's where my realization really hit: many of them do have perfect bodies, and see where it gets them?), and then, just under the wire, "commitment." And a family. Their old girlfriends, all the six-month wonders? They get to spend their fifties coming to terms with what it means to be well and truly alone, to know that they will never experience the touch of another again, and to feel the empty pride of knowing they are capable enough to be able to go out in the middle of the night while a freezing windstorm rages and get the generator in the garage started and hook it up so the basement doesn't flood. Quite a feeling of accomplishment.

There are not enough men, and always enough women twenty years younger. So there's always a lost generation of women who put their fine educations to use in constructing justifications: Hey, I've got my friends. My work. My hobbies. That's so much!

And indeed it is. Gratitude abounds. But what of the creeping bitterness? The little nagging hatefulness that comes on at nine on a Friday night, just you and the newspaper and a glass of wine? What to do with the wish, just once, for someone with whom to talk over the wisdom of this car over that, saying this to your child instead of that, staying in for dinner or going out? Well, you shouldn't feel it.

Usually, the people who tell you this with such conviction are those who are paired. (And the notion of pairing: It just feels so natural, so like the summer rain; all of those millions of us in our separate households, with our separate bills, might be excused for a primitive wail into the silence: Isn't this stupid?) They usually tell you, a little too quickly, how sick they are of their husbands' neediness, their selfishness, their bursts of critical unhappiness. At least you don't have to deal with that. But I tried to explain it to one of them once like this. If you get a flat tire, who's the first person you call? And if you find a fifty-dollar bill on the sidewalk, who's the first person you call? It's the same person, isn't it? Well, some of us have no one to call. We share it with no one. The frustration and the happiness both. A closed system of one.

The author of the piece, after explaining the causes for this state of affairs, ends at the same place as the apologists of the single lifestyle. Isn't it wonderful to be in the company of other lonely women?

She never contends with the simple, central issue--what to do about the primate, its inborn needs and its skin? You can't talk that away. Flowers, a ring. Another. You can't think that away. You can only swim.

December 24, 2011

These Too Are Gifts

We went down to the city of the past and the present. We rode the bus. One of the aims, besides encountering the serendipities a visit to the place always provides, was to see the bonsai collection at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden; the boy has become fascinated with these frozen moments, these living paintings. One thing led to another. We arrived a half hour before closing time, in a foggy gray drizzle. Only it wasn't a half hour before closing, it turned out. We walked past the windows, through which we could see people standing in the room of miniatures, gazing in silence, and when we reached the door we found it locked. A guard stood on the other side, shaking his head.

We went down to the city of the past and the present. We rode the bus. One of the aims, besides encountering the serendipities a visit to the place always provides, was to see the bonsai collection at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden; the boy has become fascinated with these frozen moments, these living paintings. One thing led to another. We arrived a half hour before closing time, in a foggy gray drizzle. Only it wasn't a half hour before closing, it turned out. We walked past the windows, through which we could see people standing in the room of miniatures, gazing in silence, and when we reached the door we found it locked. A guard stood on the other side, shaking his head.Because I had, for inscrutable and unfortunate reasons, seen the tree at Rockefeller Center by myself while the boy was still downtown, and I was saddened that he had not had the experience, I was now determined he should not miss another thing. He would especially not miss this, for which we had spent hours of travel time. I stood there and gestured, with what I hoped was a pleasant but pleading look on my face. "We're closed," he said as he cracked open the door.

I won't retail all that I said, but it was a lot. And, though he hesitated--"If I get in trouble for letting you in . . ."; "Then I'll tell them that it was all my fault," now that my foot was almost literally in the door--he relented. "Thank you. You've made a child very happy."

And indeed he had. The quiet beauty of the trees resisted time. Amazing us. Yet only five minutes had passed. On our way out, I touched the guard's arm. "You are a good man. Merry Christmas."

We walked down the street, entered the museum next. After we had wandered through four floors, just aimless and seeing what we felt like seeing, not talking too much, we went back down and sat for a moment in front of a temporary piece in the atrium. "Movable Garden," it was titled: a long brick trough of dirt in which hundreds of variously colored roses had been stuck. If you took one, the placard instructed, the thing to do was to pass it along to a stranger.

I called Tony on my phone. This was another aim of the trip: to say goodbye to Fannie, Tony's dog and my god-dog. Fourteen years before, we had found her as a puppy wandering alone in Prospect Park. She found us within five minutes of each other, almost simultaneously, even though we were not aware at the time, being on other ends of the park, and she further bound us together. She had always been one of those extraordinary beings, a spirit dog. We loved her with everything we had. And now she was dying.

Tony picked us up in his van. We didn't have long before we had to get on the subway again, to make our bus home. Fannie had lost so much weight. Her bones stuck out, and her fur was coming out in clumps. I am not sure if she recognized me. The boy put his arms around her; he loved dogs almost as if he were one. He gave Tony the white rose he had selected.

While the boy ate some pizza at a table indoors, I finished mine outside on the sidewalk while Tony and I tried hard not to cry. I do not like goodbyes. He said Fannie would barely eat. Not even pizza, or cheese? No, not even that. But I held out a piece of crust; her eyes had been distant, but now she took it gingerly in her mouth. And chewed.

To a passerby with a dog who stopped to chat, Tony recited from memory the inscription on a stone in Greenwood Cemetery. Underneath the aged soil rested a dog, the only one in this graveyard. She had belonged to Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine. Tony had named his dog after Howe's. Fannie.

O

nly a dog, do you say, Sir Critic?

Only a dog, but as

truth I prize

The truest love I have won in living

Lay in the deeps of her limpid eyes

Frosts of the winters, nor heat of the summer

Could make her fail if my footsteps led

And memory holds in its treasure casket

The name of my d

arling who lieth dead

Soon we were on the bus north, to home. The boy fell asleep against my shoulder, and all was as it was supposed to be. Beginnings, endings, and in between the gifts.

Tony, right; Jupiter, in Santa's lap; Fannie, center. Prospect Park, 2009.

December 17, 2011

Oh! Tanenbaum

When I was a kid in the city (of course, I never was a kid in the city, but 24 looks sufficiently childlike at this remove, when I thought I was an adult but I was living instead in that netherworld between youth and adulthood, walking a swaying bridge between the two), I always celebrated my birthday the same way. I gave myself a tree.

Out I would venture in the dark to some otherwise barren quarter of Hoboken, where a December tree seller had set up shop on a street corner. The trees had appeared in the nighttime bringing with them the scent of elsewhere, the perfume of a place I called nature. Breathe deep; close the eyes. The animals of the woodland creep closer. Inhale the piney freedom. Then open the eyes. Hoboken's wildlife--rats, chihuahuas on leash, and teenage boys bearing boomboxes as big as steamer trunks on their shoulders--reappears. Oh well.

Inside my railroad flat the tree would unleash its smell, and I would get busy decorating. Some of the ornaments had been made by friends, and delivered to a tree-trimming party that was probably the smallest gathering the world has ever known, as my apartment was something like two hundred square feet. The tree--even the smallest one I could find, from the $15 rack--now occupied one-fourth of the available real estate.

No matter. I proudly, happily, placed dead center my favorite friend-made ornament: the logo from a Ritz cracker box, a bit of red yarn glued to it, and to that a small caption: "Robert Venturi is God!" Can you guess the profession of its maker? Three and two don't count. Yes, architect.

Oh, and the other tree-trimming tradition: "Messiah" pouring from the stereo. Good thing I was alone, because I sang along. Always. Loudly.

Christmas trees date back some five hundred years, to eastern Europe. At first, people would sing around a tree in the public square, then light it on fire. Later, this would sometimes happen in people's living rooms, as evergreens were decorated with live candles. But that almost seemed worth the danger to me; although I only ever got as far as white mini-bulbs, I envied the few friends who braved the risk for an incomparable, transporting vision of a green tree alight with dancing flames.

My tree this year, as ever since I moved here, comes from the advancing woods retaking the open fields. A giveback, then. And even more of one to me, since all this land is now owned by New York City. I'm sure they wouldn't mind, right? The tree is always lopsided, having grown toward the sun on its own terms, with two crowns.

We just finished reading a book on the Christmas truce of 1914, my boy and me. What a cheering, and depressing, story. The former, because it proves that when we come to know one another as men, as friends, we no longer wish to kill. The "enemy" is destroyed, when he is no longer the vilified unknown, when he is just like you--sick and tired of senseless slaughter. And it is the latter, because in the true story, the officers outlawed friendship. Finally, after months of pressure later, the men were convinced to kill again. The enemy was restored.

But for a brief while, lighted trees stood on the ground of No Man's Land, bringing peace.

December 10, 2011

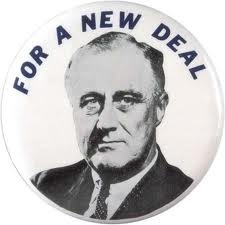

Occupy Their Shoes

Why did it take so long? Why were we not in the streets, with our placards and our anguished shouts, before this? It took nearly a fifth of us out of work--no hope of it returning, either, because it had been slipped out of our pockets while we were watching the parade, entertained by the clowns of today's narcotics (ever more team sports to show us how to be mindless followers, happy pills that simultaneously pacify us and put billions in the coffers of Big Pharma, brilliant!, the little screens in all our hands giving the illusion of Connection to Friends, jobs disappearing incrementally into automation)--before we thought to rise up. What the encampments will bring, no one yet knows. Change, one hopes. But hopes are sometimes dashed.

My coat, anyway, now sports the button I had been long wishing someone would stamp and a million wear: "I want Roosevelt again." Or at least someone with the courage to do what is necessary, no matter how unpopular, and then to proclaim (as in 1936): "They are unanimous in their hate for me and I welcome their hatred." Only bravery like this, and a willingness to put the country before a desire to be liked, aka reelected, can effect the change we need now. Because, truly, "The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little" (second inaugural).

I was in the presence of a few who seemed to have too much, on Saturday evening. The venue was the grand new luxury hotel built by the man who has brought high-stakes horse shows to the banks of the Hudson; he had to build the hotel, he explained to a magazine reporter, because there was no place in these parts that offered the kind of lodgings the extremely well-heeled horsey set demands as a matter of right. And so he built a place that exudes the right sort of silky anonymity, with high thread-count sheets and turn-down service, that is expected by the one percent. He is also the parent of children in my son's new school, and that is why I was seated near the fireplace at a large table at the lavish buffet in his hotel's two-story banquet room, for the school's annual fundraising auction.

The items bid upon ranged from gift baskets prepared by every class (the seventh grade's was a game basket, for which I'd bought Scrabble and a dictionary), a chance to be headmaster for a day, a custom-made dining table (value, $9000), a Cape Cod house for a week (value, $2700), lunch with Entrepreneur of the Year (value, priceless), and a "dream car tour," enabling one to take for a spin, one after the other, a Lamborghini, Bentley, Aston Martin, Maserati, and Mercedes. The one I wished for, though, was "Fighter Pilot for a Day," at the controls of an Italian light attack fighter. Then I could die, feeling complete.

The paddles were raised all around the room, blinking on and off like explosions in a video game war. And indeed it was a game, only played with real money (we had given our credit card coordinates before being seated). I noted the frequent bidders always sat back in their chairs, as if resting while servants (volunteers with clipboards and fast pens) recorded their thousands tossed off with an insouciant flick of the wrist. They seemed to enjoy it. The next thing I knew, auction fever spiked my temperature for a brief, hysterical moment, and in a single flash of my paddle--wait, who did that?--I had given away money I didn't have, so that the kids might have a weather station with Mac and six iPads and dock. Then I came to my senses. I went back for some paella and put the paddle safely into my bag so no more temptations would call me out of my place firmly with the 99 percent. Those who had no access to an open bar and chocolate-covered cheesecake slices.

For one night, I stood in their shoes. And I knew why they didn't want to give this up. But I also knew why we must fight so that they will.

Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson's profile

- 19 followers