Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog, page 6

July 16, 2011

Concern File

What is important?

What is important?It depends on where you sit and what moment you ask the question.

If you are struggling with something--and who isn't struggling with something; I used to believe everyone else was happy and confident, but now that I'm older and wiser, I know that anxiety is pretty much everyone's little companion--it's hard for the worry du jour not to become the world. The front page of the paper is just that: paper, thin, and replaced in twenty-four hours by another sheet with grisly color photos taken in some other world. One so terrible it can't be believed.

The most powerful biological urge in the undamaged psyche is the care of one's offspring: it is this way for you, for me, and for the milk cow whose calf is taken from her and for whom the anguish is vocal, and complete. It is the same for all parents.

The Somali people are stumbling toward Dadaab, Kenya, on journeys of more than a month, to reach what is now the world's largest refugee camp. They are trying to escape drought-induced starvation, and their children are falling by the wayside. Can you imagine this? Your small child, malnourished, thirsty, forced to walk day after day until he can go no farther, and he drops. The reversal of nature's order turns the universe on its side, and everything falls off into clattering ruin.

The magnitude, and the raw agony, of such a situation makes the privileged feel paralyzed, at least for a moment. A little while ago, it was Japan: and we couldn't wrap our brains around that, either. Although there were a lot of benefit concerts to aid that ravaged country. I haven't heard much about Japan recently. I also haven't heard about many charity art auctions for Somalia. Maybe it's too big. It's been going on for too long. It's too far away.

First their animals starved. You can do an image search--"Somalia drought" is all you need to type in, and 628,000 results later you are drowning in the horror. Small children whose bloated bellies over spindly legs and empty eyes define the word "wrong." The adults who know what's coming for them, unstoppable, and they show it in fearful faces. Goats and camels, skeletons with hair, some still walking, most only a few minutes away from the final groan, the drop to the knees that will be their last. The people, the people, ground down to bare life. Nothing more.

I will not point out the awful disparity between our lives, even those Americans who are struggling in this economy that assures so much to so few, and tells the rest to go to hell, and people who are dying by the million because they have no water and no food. It's a cliche to mention that I just bought whatever I felt like buying (watermelon, bread, strawberries, olives) at the grocery store, and still I have worries that keep me awake some nights. What is wrong with us? Do we not do anything because we don't care? Or do we not care because we can't do anything?

It's a messed-up world where those who have too much can't even reach those who have nothing. And are about to fall over the edge.

Yesterday at the farmer's market (the line for felafel sandwiches, $8 each, was about twenty-five people long), I ran into an acquaintance I hadn't seen in a year or so. A brilliant writer. She smiled and told me I looked wonderful: "It's so nice to see you. How are you?" I told the truth: really well. But the question returned caused a strange look to pass over her face, even though she said, "I'm pretty well." Maybe it was the half-beat pause before the adjective. "Pretty well?" I asked. "But not great, right?" All of a sudden her visage collapsed, the happy-to-see-you mask. "My daughter's just been diagnosed with cancer."

The universe is tilting for her, and things are beginning to slide to one side, precedent to falling off. We would do anything for our children. It is an imperative written into our cells. Their survival is our concern. The only one that matters.

Published on July 16, 2011 06:14

July 13, 2011

Shameless Self-Promotion

Published on July 13, 2011 13:50

July 9, 2011

Be Here Now

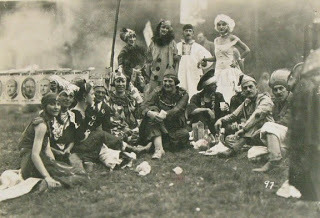

I live in history. I live in a place that is not the place you think. That is to say, I live in Woodstock. (All right, near Woodstock: the town that I live in is no town at all now, being located on the barren rocky floor of a New York City reservoir.) It has long called to artists; the picture here was taken in 1924, at one of the annual Maverick festivals held on social activist Hervey White's farm, to which he invited all sorts of outcasts and Greenwich Village "bohemians," who scandalized the local farmers.

I live in history. I live in a place that is not the place you think. That is to say, I live in Woodstock. (All right, near Woodstock: the town that I live in is no town at all now, being located on the barren rocky floor of a New York City reservoir.) It has long called to artists; the picture here was taken in 1924, at one of the annual Maverick festivals held on social activist Hervey White's farm, to which he invited all sorts of outcasts and Greenwich Village "bohemians," who scandalized the local farmers.It was just a place to which they came. They hardly knew, or chose, where exactly it was. It could have been a little farther into the Catskills, say Fleischmanns, for all they cared (it was not; later, that place would call to the Hasidim, who likewise scandalized the locals, but for different reasons). But it was a good place--the perfect place. All an artist needs is endless green views, miles of woods, a few hard hills to climb, and stuff to make costumes. Then bring on the wine.

Years later, and the musicians came. Notable among them was Bob Dylan, who brought mystery to Woodstock.

He was becoming famous, as was his destiny, if not his plan. He was often seen zipping around town, from and to his house in the Byrdcliffe artists colony, on his '64 Triumph T100. In July of 1966, he either did or did not crash said bike on Streibel Road. It's certainly a crashable road: it climbs steeply up from 212, Woodstock's main street, nearly opposite the Bearsville complex that housed Dylan manager Albert Grossman's recording studio, then Todd Rundgren's Utopia studio, and now a theater, radio station, and fancypants eatery at which all Woodstock society (read: New York City expatriates) comes to see and be seen. History rolls on, from the past directly into the present, merely changing casts.

The bike wreck may or may not have occurred; some have speculated it was a publicity ploy. At any rate, it didn't hurt Dylan much, even if it did crack a vertebra. He got famouser and famouser. Then he left Woodstock.

And then Woodstock left Woodstock. The famous music festival that bears its name was supposed to have happened here, but wasn't; it was about 66 miles distant. Perhaps this has saved the real Woodstock. Or perhaps not, since there probably wouldn't be this new generation of stoners hanging out on the village green, or shops selling tie-dye and candles and pipes (not to mention triple-milled soaps and cashmere sweaters) if the mistake weren't rather easy to make.

There aren't a whole lot of mavericks, or artists, in Woodstock anymore; it's too expensive. There are film people, and music industry people, and industry industry people, and their gorgeous modern houses up in the woods, or their gorgeous old farmhouses with beautiful and vast gardens in the valleys between peaks.

But it's become my town too, by accident. Or fortune. These are the same things, I believe. The town park is the ground that Nelly and I love best, of all places. There will never be a day, I hope, that I don't walk into the meadow and gasp at the sight of the mountains rising up on the other side of town, magisterial, implacable, eloquent in their silence. Then we turn and go into the woods. We are refreshed by the water of the creek; me, by its permanent flux, Nelly by the cool wet of it on her long tongue.

Woodstock is not my home--home is the place that grew me, the place that sent its minerals into my sap through the roots, the place that will never leave me though I have left it. It is always there, underneath, bedrock anchoring me. It is the place that I start breaking the speed limit as I approach on return, eager to see: as if I might turn the corner in my old neighborhood to catch sight of myself, riding fast down a brick-paved hill on Delaware Avenue on a green Raleigh, the English racer that long ago disappeared from the stairwell in another home, Brooklyn. It is the place that visits me, strangely, as I lie on my back on the sticky mat in yoga as the teacher intones "Peace in your hearts . . . " I see Ohio then. I feel Ohio then.

Woodstock is temporary. I walk its sidewalks in the footsteps of the departed, Dylan, and Hervey White before him, and a hundred others who have come and gone. It is home, for now. Maybe it will visit me, too, in years hence when I am told to not hold on to anything, to let it all go.

Going into town: this is a way of saying "rejoining society." When I need the feeling that I belong somewhere, to the strange tribe that has gathered to make something of our lives, I go now to Woodstock. It is a fine place. It is what I have been given.

Published on July 09, 2011 08:29

July 2, 2011

Somewhere Up There

Dear Abby runs a repeating theme in her column (and yes, I am a devoted reader: where else can one simultaneously gloat over others' extraordinary bad behavior, and be chastened about one's own?) titled "Pennies from Heaven." In it, people recount their experiences with what they believe are messages from their dear departed. In an uncharitable mood, I might retitle it "Wishful Thinking"; it's such a bald case of desire remaking reality in its own image. (The intense version of what we do all the time, in so many ways, count them.)

Dear Abby runs a repeating theme in her column (and yes, I am a devoted reader: where else can one simultaneously gloat over others' extraordinary bad behavior, and be chastened about one's own?) titled "Pennies from Heaven." In it, people recount their experiences with what they believe are messages from their dear departed. In an uncharitable mood, I might retitle it "Wishful Thinking"; it's such a bald case of desire remaking reality in its own image. (The intense version of what we do all the time, in so many ways, count them.)But my smugness vanishes when I simply imagine the cold thump in the chest when the eye lands on what it believes it sees. What could be realer than the slow dawning of a sensation that eclipses every other sensation? The sensation that someone is back.

Apparently pennies are worth more as melted copper than they are as currency. People throw them away. If you feel a twinge of unrightness every time you see this, then you are officially Old. Sorry. There are signs.

We have thus all become accustomed to finding them everywhere, including our sock drawers. But in the past several days, they've been leaping at me in such numbers I started noticing, then puzzling, finally feeling a bit alarmed. My opinion on the existence of a Higher Power in the Great Beyond has been tiresomely documented here, so I don't need to repeat that. And yet . . . (The great hallelujah in life: the opportunity to say "And yet . . . ")

Someone is trying to tell me something. And either that someone is a masterful magician, or else I am wrong in my scientific suppositions. Then again, that someone might well be in me. Perhaps I am trying to tell myself something. But how'd I get all those pennies to appear?

On the seat of my car. At a table in a restaurant. In my pocket. In the tankbag of my bike. On my bedside table. On the kitchen counter. Underneath my desk. Yesterday, at Trader Joe's, I heard a clatter, and a penny was rolling toward my foot. It stopped right in front of me. I looked up, but everyone was busy perusing the organic lemonade and sea salt potato chips.

Was I about to get lucky? You have no idea how much I need it, right now. Or so I think. I am aware this has dangers: Luck is not delivered. It is made.

(My brother-in-law, a crack backgammon player, was once smearing me all over the floor in a game. He threw doubles after doubles, racing around the board while I stayed still, taking the hits. "You are so lucky!" I exclaimed after he threw double 5s, again. "A good player makes the dice look lucky," he replied, and I heard this with the unmistakable press of truth. Look: I'm retailing the story twenty years later, so it made an impression.)

In a moment of despair, questioning everything but getting stony silence for answers, I phone a friend. Well, at least there's one thing that's right in my life right now: wonderful friends I can call when in despair. Finally, I tell her about this . . . this weird occurrence. The plethora of pennies suddenly coming to me. I feel strange as all get-out relating it. But I know she won't laugh.

Instead, she assists me in crawling toward the first answer I've had in a while: maybe, she says, it's my way of reminding myself that in order for something good to happen, the initial step is realizing how much good I already have. The anguish re-frames itself in that moment: Maybe things are going to be all right after all! I take my hands from the iron railing of the figurative high bridge over the hard gray river. I turn and start to walk again. To the other side.

At that moment, holding the phone against my ear, my eye stops roving--over the roofline, the sight of the chimney cut out against the sooty clouds, the branches of the pine swaying. It is drawn downward. I am still laughing about the pennies from heaven. That is when I see it. A penny, right under the footstool of the deck chair I am sitting on. I am saying the word, and here is the thing.

Yes, here is the thing.

Published on July 02, 2011 06:22

June 25, 2011

Not-So-Total Control

On Friday night, I drove my son back to the school he had left on the bus four hours earlier. Now, though, it was a transformed place: no longer just a place of boredom, occasional interest, even more occasional tears. It was the place where a milestone has now been planted deep in the earth, the place of the First Dance.

In the car we approached the cafeteria door, my son wearing the jeans he had worn all day but with the addition of a button-down shirt, not tucked in though (fashion-immune, my son nonetheless had a small moment of panic a half hour before we left: "Oh, I wish I'd asked somebody else what they were wearing!"). The door of a car before us opened, and from it emerged a . . . a what? A girl-woman, in high-heeled silver sandals. A slinky dress. And blonde hair arranged as if by paintbrush into a multitude of glistening arcs, each held by a rhinestoned clip. I had a sudden understanding why none of the boys I liked when I was this age liked me back: we were living in different countries, in different centuries too, that's why. My boy, who still plays with Legos and is in his All Weapons, All the Time phase, does not exist in the same space-time continuum as these girls. (I now saw a gaggle of them crowded around the door, pointing to their friend; they were nervous as all get-out yet dressed to thrill).

He grimly opened the door of the car--I know he would have pled with me to keep driving and take him home, but for the fact that those six girls had spied him, too--and without a word of goodbye got out. As if there were a noose hanging from the disco ball in the decorated cafeteria, just waiting for him.

I know the anxiety. It doesn't just disappear all at once, when we leave sixth grade behind. ("Oh, I've mastered all that. I'll never again care what others think of me so much it keeps me awake all night. I'm done!")

I still have it, if in slightly reduced form, when I go to a party where there are strangers. I still have it, when I get up to read in front of an audience. I still have it, when I feel judged by an editor or the panel of a prize committee. But nothing ratchets it up quite like publishing a book. That is where I am at. Every step along the way--getting back the edited manuscript (I let it sit, in its unopened FedEx envelope, on my office floor for two weeks before I mustered the courage to open it); seeing the first jacket designs, like the prom dress you will wear on what feels like the most important night of your life, and then the fights where you implore your publisher to take off the frilly sleeves and remake it in something other than scratchy polyester; the interminable wait while a list of eminent writers decide whether or not your brand-new baby is worthy of a read and a comment for use as a hook on the back of the jacket (in today's new publishing world, apparently not, I've learned).

There's more. Much more to make my stomach lurch in the coming months.

The day after the dance found me in Troy, New York, in a blazing hot parking lot. I was there to take a Total Control riding clinic, the culmination of a dream first dreamed two years ago when I witnessed one at the BMW MOA rally in Tennessee: Is it possible that I could ever ride like that? I wondered as I saw riders inscribing small but precise circles at even speed, inside knee kissing the tar.

I worked hard. I tried hard. My clothes stuck to me as if they had been painted with glue, and my helmet was damp whenever I put it back on. I hope I learned; I felt as though I didn't, but the instructor insured me I would realize later that I had. I will try to treat it as a fun game, as they taught; I will not let my anxiety turn my frontal lobes off while it consumes the primitive brain stem. I will control my out-of-control fears about not doing well enough, not writing well enough, not looking cool enough at the dance.

One student in our class stood high above the others. One student moved elegantly, precisely, an instant master of every exercise. At the end of the day, I turned to her. "I want to tell you that you are the prettiest rider here--both out on the course, and when you take your helmet off." She smiled widely. She was indeed pretty; what I envied most, though, was her skill on the bike.

"What's your secret?" I asked conspiratorially. But I didn't really expect her to be able to tell me such a thing. It had to be too big to voice.

It turned out not to be.

Her smile widened as if to light the whole world. "A life lived in joy!" she explained.

There is no question to which this is not the appropriate answer. I left there thinking on this all the way home. A week later, and it is still in my mind. When it's my turn to go to the prom, I hope I can remember. But better than that, I hope it's soaked all the way down. So that it's everywhere, in me and all the potentially lost moments of this life.

Published on June 25, 2011 06:08

June 18, 2011

Copilot

It took a while. It always takes a while for the road to run through you, so you can run through the memories of the road. These come back, not strangely at all, as you ride the current road. This is how you know what that trip really meant, by visiting other landscapes (which will in their own time be recalled at a distance). I never wrote about that monumental trip of last year, because until now I did not know what it was about. I know what it felt like. But it did not have a story to tell, until I put my son on the back of the bike again last week.

It took a while. It always takes a while for the road to run through you, so you can run through the memories of the road. These come back, not strangely at all, as you ride the current road. This is how you know what that trip really meant, by visiting other landscapes (which will in their own time be recalled at a distance). I never wrote about that monumental trip of last year, because until now I did not know what it was about. I know what it felt like. But it did not have a story to tell, until I put my son on the back of the bike again last week.I remember one moment of terror, out west last August. My child, the most precious, necessary thing in the world--without whom, I am lost--is sitting behind me. Most of the time, he squirms. If our riding partner is behind us, my son turns suddenly, shifting his weight near disastrously, to make certain he is back there. (No matter how many times I have told him I will always keep our friend in my rearview mirrors, and will stop immediately if something happens. No matter how many times I have told him he must not move around, especially when we are moving slowly through narrow gaps in traffic--yoicks!) He suddenly decides he needs to look at the ground under the left side of the rear tire, throwing all his weight left as we approach a stop sign; I have lost track of how many times I was this far from that mercuric white panic: S**t, we're going down!

But the particular moment I was recalling had in fact been preceded by a long, long period of calm happiness. It was so pure, in fact, I was not aware of anything at all: I was completely inside it, riding-happiness, thick and creamy and sweet. Then, suddenly, I was aware of it, which means I was aware of something wrong. By way of something right: I had been riding along for many miles not feeling anything but the machine propelling me through air and time. There was no demented sprite of the ether pulling the bike to right or left, no brief gasps or injections of adrenaline.

My child! He fell off the bike ten miles ago!

I thrust my hand behind me and felt his leg there. Oouhh. Jesus H. Christ. That was scary.

He had just been . . . quiet. Perhaps he too had entered that whipped-cream cloud, riding-through-peacefulness.

Now, in central New York, on our way to a seminal destination, one I had been thinking of taking him for several years and was here en route at last, I was back on the roads of what has passed into my own history, the thousands of miles that traced our manifest destiny. I looked and saw again what I had seen then. A sight that moved me so profoundly I never found words for it: the vision, in the mirror, of how he was occupying himself back there behind me, so close and yet so far. He was testing the air, arm out. He was flying along, to wherever I would take him. Seeing his hand held against the air, a tender wing, called up in me so many different emotions I could not count them all. It resisted, just slightly, the pressure of the wind. And I realized then: the pressure of youth, of years, of himself versus all else.

That is what he did last year, too. That is what I remember. Only now it is a story, not just a sight.

We parked the bike and walked up and down the main street of the quaint and lovely town. We got sandwiches--"the second best grilled cheese I've ever had, Mom!" [do you remember the other?]--and walked down toward water's edge of a glistening lake. I took my feet out of my riding boots and cooled them in the grass as we ate, at the foot of the statue of an Indian, in James Fennimore Cooper territory. As we headed back to the bike, ice cream was promised for later (as it always must). In a few more minutes, we were there.

Up the circular drive, to sit idling under the portico. Sliding glass doors, nurses entering and leaving, checking their watches. An empty wheelchair waits. I turn to my boy. "Through these doors we came, eleven years ago, and you breathed your first breath of the outside air." I could see it all suddenly then: the trepidatious mother, hand tight on the car seat in which her baby was strapped, watching through the glass for the arrival of the gray Toyota. And then . . . outdoors, into our new life.

It was as if it were yesterday, but also someone else's life I had watched in a movie. O strange disjunction of time and events!

My son did not feel all these things last Friday, as he of course could not. They were mine alone, because they were his. The road had not yet moved all the way through him. Someday it would, and this moment in this land would finally come to have a story. That is when he will remember.

We pulled out of town. In a little while we were in the place I wished I could tell him about, the place we had lived before and after his birth, the place where every road was known, every byway had something to tell me about who I had been, and who I was not now.

Published on June 18, 2011 06:18

June 11, 2011

If Wishes Were Horses

Sometimes you'd wish something so hard it felt as if something inside you might break. As if wishing it would bring it into being, changing all of history behind you. And you, sitting on the fulcrum of this world, could change the years to come because you changed yourself.

Sometimes you'd wish something so hard it felt as if something inside you might break. As if wishing it would bring it into being, changing all of history behind you. And you, sitting on the fulcrum of this world, could change the years to come because you changed yourself.That is the way it was with me, in the days I wished I was an Indian.

I looked into the mirror, at my shiny dark hair. Hey, that could mean I'm an Indian! I looked at my family, and decided that since they didn't "understand" me (who could?), it meant I was adopted. Oh, how I wanted to be adopted! That would explain everything, and also give me the hope of what I wanted to believe: that I bore in my veins the blood of the noble, true people. I wandered the woods collecting things of the woods; I spent hours alone there, imagining being captured, or capturing in return. I walked with my toes in, as I was informed the Indians did, in order to move silently through the woods.

All summer long--oh idyllic Ohio summer!--I went barefoot. (Do children still do this today, or is it another sensuality lost, the heat on the sole, the gravel ouch, the cooling grass?) And when I came home, my parents called me Melissa Blackfoot.

Did they know how much I wanted this to be true? Their joke was my dearest hope.

The Blackfoot people, of the area that is Montana and Alberta, Canada, were the "Indian" Indians--they were the ones with the tepees. They used dogs to pull travois, until they were introduced to horses in the early eighteenth century. These they called "elk dogs."

The Blackfeet had the honor of becoming the first natives killed by the encroachers who called themselves Americans, but were not. At first trusting of the Europeans, they soon realized, as did all their confreres, the trust was misplaced. When they learned the men of the Lewis & Clark expedition had traded guns to their enemy tribes, the Shoshone and Nez Perce, they attempted to steal the guns back. One warrior was killed.

They believed that each day, it was a perfectly new sun that climbed over the eastern horizon. How profound a philosophy, how purifying a therapy, this is has only dawned on me now.

I did not know any of it when I was a child who wanted to be an Indian, but was merely a little savage. Indeed, if I had, the flames of desire to be one of them would no doubt have burned hotter. Murder and injustice--now there was something I could really have wrapped my imagination around.

Published on June 11, 2011 06:15

June 4, 2011

Digressive

For twenty-five years, reading the New York Times every day was as close as I got to religious observance. Usually by the time the coffee pot was empty, the last page had been turned.

For twenty-five years, reading the New York Times every day was as close as I got to religious observance. Usually by the time the coffee pot was empty, the last page had been turned. Sometime in the dawn light it had been thrown against the apartment house door--thwap--in the blue plastic bag that found second use as the ideal urban dog waste bag. The contents of every street-corner garbage can in the city was at least half composed of knotted blue bags.

Then we moved to the sticks, and had to drive to get the paper. So we did. Every day of the week. Sometimes it was sold out, so we just drove farther until we found it. When we moved to a more civilized part of the sticks, it was again delivered, to the end of a long drive, but still before we woke. I had a small child by then, therefore I couldn't read it in the morning. And so it became the pre-bedtime ritual. As with all rituals, it served many masters: desire, need, addiction. I sort of knew what was going on in the world then; I felt the need to know. Not that the Times is everything: it has a smarmy self-congratulatory residue all over it; its idea of "balanced" journalism is to counterpose obvious truths against fringe lunatic views, just so there are opposites presented; it is clearly in thrall to its advertisers (one is never going to read an expose of fur farming or diamond mining in its pages). It made me mad as hell. But I was used to mainlining it. I had to go to the Guardian to find out what was really going on in the world--it was astonishing to read in its pages stuff, even stuff our own country was doing, that never reached the paper of record.

I don't read it anymore. The paper version is not delivered in my neighborhood (jeez, moved again), and I simply can't read it online. I haven't got the hang. The paper does not crinkle in my fingers; the sections don't look the same. My ritual has been deconsecrated.

But people still send me links, because they're still reading that paper. The one I got the other day was to Jonathan Franzen's op-ed piece about loving and technology. Or maybe it was about life's pain and the horror of blind consumerism. Then again, maybe it was about sadness and narrative. I wasn't entirely certain, by the time I got through. But I was clear on one thing: Like the bags the paper came in, the piece had been recycled (it was written as a college commencement address). A writer of his stature is simply not going to get paid once for a piece. Not when he can double- or even triple-dip.

Although it never said so directly, that is what I suspected about his recent essay in The New Yorker. It was about the death of his friend David Foster Wallace. It was also about revisiting the site upon which Robinson Crusoe was based, as a way to discuss the novel. Oh, and it was about loneliness and, tangentially, stupidity. Also about birdwatching as a way to order the world. (I didn't believe for a moment, though, that he "just went" to the island to get away and get his head straight: a writer of his stature doesn't do anything without intending, first and foremost, to write about it. What do you want to bet he'd inked the contract with the magazine well before he started looking for flights? That was the one thing--perhaps the only subject of central importance--that didn't make it into the article, though it hung over the entire thing for me.) He cycled around all manner of material. And when he was through, he double-dipped. Yes, folks, he sold the movie rights.

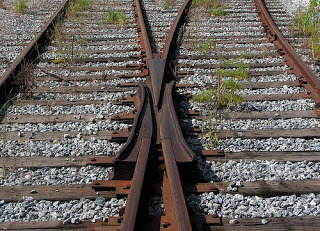

I am not griping here about Franzen. I do not find it a problem when writers recycle their blue bags. I never bought the idea (as you can certainly tell) that one piece of writing should contain only one idea. Instead, I know all too well that when you set out on one track, the cars sometimes get switched onto another track. That is, quite literally, life. I started in one place, then moved to another, and another, and another. (How many of us are still living in the same place we were born, much less living in the same head?) I think one thought, and it takes me to another, and another, and another. Sometimes I return to my starting point, sometimes I have no interest in going back there at all, because I've been drawn to something far more interesting.

Digressions are life. Or maybe life is digressive. Let me think about which. For now, I return to the beginning, though not the beginning of this--I'm no longer thinking about the New York Times. Writing takes you on a one-way track to elsewhere; the only problem I had with Franzen's essays, I realize now, is that he tried to tie it all back up into a single subject, which felt to me a bit like pandering. Profound ideas will not be circumscribed, even if they will cohere.

Years ago, I started writing here about one subject. But then life came along and threw a firecracker on top of my head, and blew the one idea to bits. Those are still widely scattered. Now, I've decided I like them that way. I can follow their trail, which takes me away from the place I began.

Published on June 04, 2011 06:04

May 28, 2011

Chance Brings Us Here

There was the sense of flying: air uplifting, lightening the weight of the body, and wings given by the engine below, just forward of the seat. And I wasn't really in the seat, or even on it. It was just a suggestion of a support. For a moment it was only me, a body detached, flying through the air of the Berkshires. Cresting a rise in the road, a voice cried from within: You are so lucky!

There was the sense of flying: air uplifting, lightening the weight of the body, and wings given by the engine below, just forward of the seat. And I wasn't really in the seat, or even on it. It was just a suggestion of a support. For a moment it was only me, a body detached, flying through the air of the Berkshires. Cresting a rise in the road, a voice cried from within: You are so lucky!Lucky to be riding roads through a world still so beautiful as this one, lucky to be in this company, lucky to be at the endpoint of a thousand events (man's creating, odds after odds after odds, a machine such as this; three hundred years of English expatriates and their succeeding lineage grooming this landscape; all of history meeting in one impossible moment of a spring Sunday with me sitting at its very peak).

How I came to meet these people--a friend from twenty years and two lives ago; a new friend met by chance two years before, because a mention and a moment seized (and not that other one, or for that matter any of the dozens of possible others); another new friend who, though rarely seen because of distance and whatnot, still feels ineffably close--is either impossible to calculate, or is the only thing that could have happened.

***

Just because unexplainable things happen does not mean we need to find an unexplainable cause to explain them.

***

Lately I have been having conversations with several girlfriends who are desperately unhappy with their situations. Money troubles press in, or else money is not a problem, but there seems to be no time in the day, in the week, for anything but taking care of houses and children and husbands--Did I get a degree in English in order to make endless grilled cheese sandwiches and deal with car repairs and home renovations and arguments over how long he needs to be away for work? My only response to this unanswerable lament came a few weeks ago, when I found myself riding through a small backwater near here, one that oppressed me for the entire length of the red light during which I was trapped in it, when I realized, "Hey, I should remind them we could have been born in Wawarsing. We'd never have gotten out alive." There would have been no regrets that we could have done something with our fancy-college degrees, because that would have never presented itself as an option. Like our parents and grandparents before us, we would have graduated high school with a couple of babies already, and no chance to climb the stairs to see above the low roofs of our small place in life.

I could have been born in Wawarsing. But I wasn't.

To what do I owe the extraordinary luck of being born where I was, into a life that was nothing but an ever-rising staircase? Born into the extraordinary way the dice fell, clattering on the tabletop: doubles.

It would be more seemly to post here the results of my 2010 tax return, or my preferences in horizontal activities, than to delineate my beliefs on the existence of any higher power, but thinking on the vagaries of life does not make me feel entirely polite. So, the stone atheist finds herself sometimes bemused to the point of exasperation when she thinks in private on this subject. The only thing that gives pause to the forward march of her certainty is the fact that many people of far greater intelligence are equally convinced that she is wrong. She must be missing something, because it all seems quite simple to her. Anything that can think, will, or conceive must needs have a brain. A brain is a physical entity that evolved in vertebrates and some invertebrates. It is composed of cells. Although the universe is more filled with mysteries of which we know nothing than of discoveries we comprehend, it still seems impossible that a nameless something, even as great a one as god, could express a motive without having a brainstem. Where might this all-powerful mind be hiding its neurons? They would have to be very large.

Yet to me the mind-blowing complexity of everything is easily explained by a single phenomenon, one that does not require physicality: chance. Beautiful, awe-inspiring chance. It was by grace of this supreme mechanism that my particular conglomeration of flesh, will, and bones was poised atop a hideously complicated machine of German origin on this particular day in the company of others who came together by such an elaborate series of luck that it defies everything, or nothing.

***

A friend's daughter was occupying herself with a book in the Where's Waldo series. In these books, each spread is an intricate, impossibly detailed eye-twister of an illustration. In each, you are supposed to find the little figure of Waldo, but he is so well hidden sometimes you never do. You have to give up, or go mad. "I couldn't find Waldo on this page at all," she tells me. "I mean, look at it!" Indeed, there is no way to find Waldo among the many hundreds of Waldo simulacra peppering the page. "So I turned away. And then when I turned back, guess what? I had put my thumb right on him."

***

At a gas stop, while we briefly shared (helmets off to talk) the separate but combined experience that is the group ride--such luck as this!--I heard my phone ringing. It was another new friend, at the end of his own ride in the same state but for another, far more epic, purpose. Riding has many, many purposes. He had attained a difficult and hard-won goal, well over a thousand miles in under twenty hours. He told me of another rider, on a similar but possibly more difficult quest during the same day and night (a twenty-four-hour rally) who had hit two deer at different times in the same ride. On hitting the first, he stayed up. Only to then hit the second, which brought him down. What were the chances of that? And he was able to get to the awards ceremony, so he was lucky. But he hit the deer, so he was unlucky. Both at once.

There would be no way for me to comprehensively explain how it was that I came to be sitting at a picnic table outside The Creamery in Cummington, Massachusetts, with a collection of old and new friends on a collection of old and new bikes at two in the afternoon on May 22, 2011. I could have been in Wawarsing, watching my great-grandkids. I could have been in Delhi (India, not New York), bent over a washbasin. I could have been an amoeba. But for one thing: luck. Incredible, inconceivable, inexplicable, beautiful luck. In the absence of anything else, I'll take it. I have to. Because the world hadn't ended the day before.

Published on May 28, 2011 06:07

May 21, 2011

This World

I had forgotten about them. Until they sent their beams out to my eye, and caught it fast. The wild columbine is blooming at the edges of the woods. One would almost think (would love to believe) that they are there, within easy reach of our too-limited sight, for our surprise: a remembrance that beauty persists. Or so we can only pray.

I had forgotten about them. Until they sent their beams out to my eye, and caught it fast. The wild columbine is blooming at the edges of the woods. One would almost think (would love to believe) that they are there, within easy reach of our too-limited sight, for our surprise: a remembrance that beauty persists. Or so we can only pray.As Nelly ran on, toward the siren call of a scent hidden at the base of some bushes--the terrible rictus of some dead beast greeted me, sharp teeth smiling from a mat of brown fur, in which my dog was joyfully rolling to daub herself with that inimitable perfume of rottenness--I was thinking about the impossibility of flowers. It suddenly came to me: Do we deserve flowers?

Just as quickly, the other part of my brain (the one that answers dumb rhetorical questions with a sneer) answered, They're not for us, silly. We are merely collateral beneficiaries. Their existence, and all their strange, complex gorgeousness, is for themselves.

As I walked farther down the road, having enticed (ok, pulled her by the collar away) Nelly from her particular Chanel No. 5, I found myself spiraling down into a pretty awful funk. I had recently seen world population projections for 2050, and a flash of angry red blinded me for a moment. It was a selfish anger, of course: I would likely not be around then, to witness the final shovelful of earth hitting the coffin of the world I had known and loved--but my child would be. In fact, he will be the same age I am now. And therefore he will not have the chance to walk down a road, near his own house, so lightly traveled that his dog can run ahead, so lightly used that he might go a mile without the scent of exhaust in his nostrils, and the mean wind whipped by a speeding greedmobile. (I know: yes, I own one. We all do, because we have constructed a society in which it's nearly impossible to live without one. No matter how much one hates them.) He will not have the wild columbine (translucent rose shading to yellow, a gilded crown for wood nymphs to wear in their revels at dusk), because there will be no woods left. Here, a mere two hours from one of the world's greatest metropolises, the fields and streams and forested hills will be stripped of all they are. To become a continuation of a single suburb, wall to wall with us.

Lately I've been dipping into a fascinating book on the science of love and romance, and from it it's clear that we possess one highly complex and powerful apparatus to ensure our survival. The tip of the iceberg is the plumage of the female of our species, done up in bustiers and what are appropriately known as f**k-me shoes. Everything we are drives to one thing, and one thing only. It's highly successful, and it puts to shame the intent of the flowers: pollinate me, they whisper to the birds and the bees, with their come-hither colors and alluring shapes. We will beat those flowers yet.

My hypocrisy knows no bounds other than the one that ends at the tip of my nose. After all, I procreated too, as I was made to do.

I turned to walk back home, after greeting the fuzzy darlings of the Canada geese, waddling yellowly after mom and dad (another success story in the population wars), and then I thought: We are running out of road. (That is in fact the title of the informative environmental website of a friend of mine; it is irredeemably true, but the scary thing is, none of us--from Malthus to Al Gore--knows exactly when. We are somewhere in the middle of a horror movie, but we don't know the moment at which the killer is going to burst through the basement door.) This road, the one I am on. And that road, the one that takes us all to the end.

Published on May 21, 2011 06:40

Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson's profile

- 19 followers

Melissa Holbrook Pierson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.