Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog, page 7

May 14, 2011

Girl Cave

The concept of the man cave is one I get. I really, really get it. Indeed, I even appreciate it: it's pretty funny. It pokes gently at the core truth of those simple, primitive desires of many men--all I need, mate, is my machines, a pretty calendar to lay my eyes on every now and again the kind with nice headlights if you know what I mean, the calming scent of gas in the air, and enough time to work on my grease manicure--at the same time it's bizarrely pre-feminist, and a touch repellent for that. It posits women as the enemy, the perennial naggers who need to be escaped.

I am here to tell you, though, it's women who need a girl cave. Upstairs or down, there's nowhere to run: the dust bunnies mock you (they have a particularly wheedling voice, too), the Lego-strewn boy's room weeps, the stovetop begs, the stack of permission slips, applications, bills, and plans looks dourly on: I bet you're not going to deal with me today, either? I thought so.

No, we're going to the Girl Cave, where we can escape into a world of relative order (admittedly because there is simply less stuff than in the main house) and where there's supposed to be dirt, so we don't ever feel a duty-shirker here. Some kitty litter on the oil stains, a quick broom, et voila. Peace, quiet, and motorcycles. Oh, and whatever's playing on the college radio station. It comes in on the radio in the Girl Cave, though not in the house. Magic, eh?

This is my secret world. There's the Lario on the right and the Teutonic Hornet on the left, ready for an oil change. (Unseen behind them, under its black shroud, is a friend's old Kawasaki, awaiting resurrection after two years--oh, what a day that will be, anticipation growing with each new arrival of parts in envelopes and boxes.) I love my small collection of parts and tools and fluids; I love that they stand at attention on the shelves, patiently waiting for their moment. I rarely get rid of anything so long as it has once belonged in, around, or on a motorcycle. This is therefore a museum of my own making, of my particular history. (To throw a piece of it away would be like, say, disposing of a letter my father wrote me when I was away at school. Never. A part of him, and of us.) Also, you never know when something might come in handy. The weirdest odds and bits can be just the things you need--they are comforts for the future. Who, for instance, would have thought that I'd ever have a Lario again? Certainly not me. But in the bottom of the toolbox I find some bolts and sockets that fit only her.

This is where I escape--from the place that would hold me back, on a Sisyphean slope where the same household tasks, done, must be redone upon the morrow. This is where I escape--to the place of wishful dreaming and forward motion.

How can you tell this is a girl cave? Here's a hint: see the chandelier?

I am here to tell you, though, it's women who need a girl cave. Upstairs or down, there's nowhere to run: the dust bunnies mock you (they have a particularly wheedling voice, too), the Lego-strewn boy's room weeps, the stovetop begs, the stack of permission slips, applications, bills, and plans looks dourly on: I bet you're not going to deal with me today, either? I thought so.

No, we're going to the Girl Cave, where we can escape into a world of relative order (admittedly because there is simply less stuff than in the main house) and where there's supposed to be dirt, so we don't ever feel a duty-shirker here. Some kitty litter on the oil stains, a quick broom, et voila. Peace, quiet, and motorcycles. Oh, and whatever's playing on the college radio station. It comes in on the radio in the Girl Cave, though not in the house. Magic, eh?

This is my secret world. There's the Lario on the right and the Teutonic Hornet on the left, ready for an oil change. (Unseen behind them, under its black shroud, is a friend's old Kawasaki, awaiting resurrection after two years--oh, what a day that will be, anticipation growing with each new arrival of parts in envelopes and boxes.) I love my small collection of parts and tools and fluids; I love that they stand at attention on the shelves, patiently waiting for their moment. I rarely get rid of anything so long as it has once belonged in, around, or on a motorcycle. This is therefore a museum of my own making, of my particular history. (To throw a piece of it away would be like, say, disposing of a letter my father wrote me when I was away at school. Never. A part of him, and of us.) Also, you never know when something might come in handy. The weirdest odds and bits can be just the things you need--they are comforts for the future. Who, for instance, would have thought that I'd ever have a Lario again? Certainly not me. But in the bottom of the toolbox I find some bolts and sockets that fit only her.

This is where I escape--from the place that would hold me back, on a Sisyphean slope where the same household tasks, done, must be redone upon the morrow. This is where I escape--to the place of wishful dreaming and forward motion.

How can you tell this is a girl cave? Here's a hint: see the chandelier?

Published on May 14, 2011 06:49

May 7, 2011

More and More

Why is it that I don't exactly feel gleeful about a death this week?

Why is it that I don't exactly feel gleeful about a death this week?I am aware that no one, including me, wants an outline of my half-baked opinions on the subject of the most notable death of recent days. For one thing, the evidence speaks for itself--and when we read between the lines, we find there a strong comment on the disingenuousness of the official statement. Of course; it's an official statement. That's its nature, eliding and eluding the exact truth. (A "firefight"? Not the word I'd use.)

For another, I don't know half enough to expound knowledgeably on this subject. I understand that a million other bloggers have already endlessly discussed the proper way to react to this news--with joy? With regret? With some manufactured, thoughtful admixture thereof?

I only know that right now I feel something a little sick and uncertain. About what has really happened, and about where it will lead us. It is a vague echo of the way I felt, exponentially more powerfully, on September 11, 2001: extremely sick, and lost in an ocean of uncertainty.

The night after the most recent event, I was talking to Mom. I found myself saying, without really knowing whereof I spoke, with some degree of belligerence: "This all began a long time ago, several wars before, so that Americans can unquestioningly continue to drive their bloody Ford Explorers." That sure ended the conversation. The very next morning, I happened to be driving behind a car on whose back windshield was written in large white letters: Thank you Navy SEALs! He is dead!!!

It happened to be a Ford Explorer.

Loving can be seen as functionally analogous to killing. Give away your love, and it comes back and back. Kill, and it too returns, more and more.

Last night, I chanced to go to yoga at a new place. The instructor ended the class with a prayer. In light of the event last week, the words sent a chill, as if from beating wings, through the air. Then we went out, my son and I, to walk a labyrinth in the churchyard. Around and around we walked, toward the center somehow.

Buddhist Prayer

If anyone has hurt me knowingly or unknowingly in thought, word, or deed,

I freely forgive them.

And I ask forgiveness if I have hurt anyone knowingly or unknowingly

in thought, word, or deed.

May I be happy

May I be peaceful

May I be free

May my friends be happy

May my friends be happy

May my friends be free

May my enemies be happy

May my enemies be peaceful

May my friends be free

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be free

Published on May 07, 2011 07:31

April 30, 2011

It's Your Country

Last week found me wandering around the nation's capital, two small boys in tow, throwing coins into every fountain I came across. As the ceremonial font of all that we aspire to be, Washington, D.C., is replete with fountains: every building and monument is approached over some regal body of water. The better to see you, my dear. Or possibly it was all one big pool of Narcissus, appropriate for the launching pad of Manifest Destiny. Every time I threw a penny or a dime, I wished a different wish. (Covering all my bases.) I discovered I have many wishes; I had thought myself a simple person, a sort of emotional broken record, but it turns out there are many, many different hopes buried within.

Last week found me wandering around the nation's capital, two small boys in tow, throwing coins into every fountain I came across. As the ceremonial font of all that we aspire to be, Washington, D.C., is replete with fountains: every building and monument is approached over some regal body of water. The better to see you, my dear. Or possibly it was all one big pool of Narcissus, appropriate for the launching pad of Manifest Destiny. Every time I threw a penny or a dime, I wished a different wish. (Covering all my bases.) I discovered I have many wishes; I had thought myself a simple person, a sort of emotional broken record, but it turns out there are many, many different hopes buried within.Today, one of them actually came true. I wish I could remember which fountain it was that I had used for this particular wish: I would get right back on Amtrak, because there are some more unfulfilled desires I could really use fulfilled about now.

There is something spooky, unsettling, and moving all at once about the seat of our government. It is too clean, for one thing. It is too tasteful, for another. The sense of a showpiece, lavishly painted and pasted thinly on top of a huge ugly mess raked up to hide beneath, is a little disturbing. There are the parterre gardens outside the Smithsonian castle--breathtaking, so European!--and then there are, a short metro ride away, lumpy gray blankets the size of humans scattered under the entryways of commercial buildings. I walked by a guy standing stone-faced outside Chipotle holding up bumper stickers for sale: "Stop Bitching, Start a Revolution," and was on the bus to the Mall before I realized I wanted one. Moreover, I wanted the guts to do what it says. If ever we needed some flintlock muskets and the will to do what's right, it's now. It's going to be too late soon, guys. I'm not talking about dumping fictitious tea into 2011's harbor, either: How DARE they co-opt the symbol of a just revolt against a tyrannical monarchy for their own selfish, imbecilic, racist, capitalistic, wasteful, ruinous ends? It's a mockery of every dead boy left in the frozen mud of the colonies. Don't get me started.

There was a different sort of discomfiture brought on by visiting the new National Museum of the American Indian. Come, let us celebrate the marvelous culture of the people we exterminated! There's an implacable sadness in the pride and beauty of the place. The original Americans exist now in statues and symbolic corn sheafs carved of limestone, and it doesn't bother us all that much. "We are Americans." We are? I'm half Greek and half English/Irish--how about you? Then again, the cafeteria in the basement of the museum is the Mall's best-kept secret, though it was out to several hundred people by the time we stumbled on it, serving what I took to be interpretive native cuisine. My son said, "Put the world's best grilled cheese sandwich next to this one and it will taste like garbage," of the Navajo frybread grilled cheese. It was damn good, but I wondered about how the Navajo might have made cheese. With difficulty, maybe.

Yet there was, pervading it all, a thrill in the air. This belongs to us. This represents us, or at least our higher selves. The unimaginable greatness of so much collected history, art, books. The grand monuments to true democracy--something we could hope for the return of, if only we could overthrow the current government, whose form might best be called corporate dictatorship.

Through a fifty-degree rain we walked, past the ever-moving Vietnam memorial. This complete and potent monument, the foot of which was laid with wet and wilting carnations, the occasional plasticized photograph of smiling boy in fatigues taped over an etched name, achingly sad, shows us ourselves. Literally: we look into the infinite blackness of its polished face, at thousands of names, and we see them printed over the image of our own reflections. We are them. They are us. Down we walk, into the earth, into a grave; then up we go again, out of the earth, away.

Through the rain we continued, to what feels to me the greatest of all that is great in our history. Up the many steps; it is a hard walk up to the Lincoln Memorial, as it should be. It should be work to get here. You should feel it in your bones, muscle. Then there he sits, as big as he was in life. Monumental. This same little boy I'd brought to this same place five or six years ago. Then, I took him by the hand and walked to the side, where what is etched on the walls has never, in the history of words, been exceeded. I started to read to him the Gettysburg Address. I made it as far as "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here--" and there I stopped. The tears were rolling down my cheeks, and something squeezed my throat tight. This time, I did not bother. I read it to myself, and the tears fell inward. Meanwhile, the boys stared up at the gigantic marble man. They took pictures, they laughed, they ran. They were free.

Published on April 30, 2011 05:30

April 23, 2011

Reading, Writing, and Resurrection

Recently I read the new book by Francisco Goldman, Say Her Name, a remembrance of his young wife, taken by a freak swimming accident in Mexico in her thirtieth year, and only a couple of years into their marriage. It is a hypnotic work, both because of the raw mastery of the writer, and also because of the morbid fascination such a thing exerts on the reader. We can only imagine it happening to us, such monumental loss, and we also think just reading it might perform some sort of voodoo to keep us safe from a similar terrible event ever visiting us.

Recently I read the new book by Francisco Goldman, Say Her Name, a remembrance of his young wife, taken by a freak swimming accident in Mexico in her thirtieth year, and only a couple of years into their marriage. It is a hypnotic work, both because of the raw mastery of the writer, and also because of the morbid fascination such a thing exerts on the reader. We can only imagine it happening to us, such monumental loss, and we also think just reading it might perform some sort of voodoo to keep us safe from a similar terrible event ever visiting us.But since we live and love, we are never safe. And this we know, as we read from outside of such shredding emotions that they can only truly be experienced from inside. It's all a big egg of paradoxes: happiness cracks open to reveal pain; "having" releases the possibilities of "losing."

Mentioning this on a certain social networking site that shall remain nameless started an interesting, if anxiety-provoking, dialogue among people who have never met one another. Unbeknownst to me, one of my interlocutors, whom I do not know personally, responded that he had lost his wife recently, his partner of decades. Uh-oh. Why should I even presume to say a word on subjects I know nothing of? --Because someone who knows much, much better is going to mow me down, with overpowering experience.

I recognized in his words--sent out to strangers--the undercurrent of anger, of wanting to collar anyone who chances by so that they might listen. Then to cry, "But you cannot know!" (And indeed we can't.) I recognized the offerings of despair--I drink too much; I fear I will never feel happiness again--as if to simultaneously say, "I need you to understand . . . you will never understand." I recognized the oversharing in a public place, because this is all you can do. You are alone; you don't want to be alone; your aloneness defines your grief, and may not be taken away.

We both know it will come and deny that it ever could. It is just too big. And we are faced with it daily, now that we have all these inputs, all these immediate yet distant ways of viewing the death of others on our little screens. Stalin understood (did he understand anything? yes, and no) when he famously said, "A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic." We have millions of deaths coming at us from the radio and the television while we prepare our dinners in the cocooning warmth of our kitchens, the heart of the home that is to preserve us in eternity of course.

And then it comes. Out of nowhere. Or the somewhere that is the life that we never asked for, but once it is here, we cannot imagine our way out of.

It is interesting that for some of us, life is a succession of partners. One after the other, jettisoned for some reason or another, even the "Till death do us part" as meaningless as the speed limit on a stretch of desert highway. Multiples of multiples. And for others, there is only one. What is spoken means everything: Forsaking all others. The binding of two into one not only through love (something I do not truly comprehend, the more I try), but finally in heartbeats, long years together of something heard in the other room and assumed to be there forever, since it is your heart as well.

How many times in a life can you say, "I love you" to different people before it becomes as diluted as those water drinks with which I try to trick my child into believing he's been given juice? "They don't taste like anything, Mom." How many times before the wheel of hope turns down toward disillusionment, abandonment, then back up into another new hope before we wish to take off the axle nut once and for all?

I remember, shortly after the rupture of the life that I had too blithely assumed was going to go on and on and on (the disappearing point in my own life, way off in the distance), a vision one lonesome night at the grocery store. Ahead of me, an ancient couple stood at the end of the checkout. Silently, slowly, with enormous concentration, they bagged their food. Together. He would pick up a package, hand it to her. She would reach over to hold up a handle of a bag in order to help him. I watched, rapt, stunned. It seemed the summation of partnership, and it was a sharp knife touching my throat. This is what I will never have. This is what I have lost! Or it was like falling and hitting my head against the ice. I watched with tears running down my face, the sudden slap of loss stinging and stinging.

A few days ago I wondered, aloud in type, about the obviously imperative need of a writer upon suffering the loss of a spouse to write about it. When this is your lot in life, to create things out of words, it is also your fate to re-create things out of them. To go over the details, to offer them up; in reciting the narrative of the past, to make it present again. The pain is never assuaged this way, but it is presented to us. We make of it what we will; the writer is a bit of a god, bringing momentarily back to life that which he lost. We see her there suddenly, alive, until the last page is turned.

Published on April 23, 2011 06:16

April 16, 2011

The Bad Seed

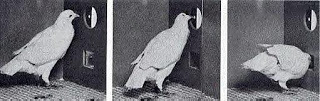

B. F. Skinner, who was an English major before he was a psychologist, came up with the lovely term "superstitious learning" for a phenomenon he witnessed when working with pigeons. It is something all higher animals, including ourselves, are prone to:*

The bird behaves as if there were a causal relation between its behavior and the presentation of food, although such a relation is lacking. There are many analogies in human behavior. Rituals for changing one's luck at cards are good examples. A few accidental connections between a ritual and favorable consequences suffice to set up and maintain the behavior in spite of many unreinforced instances. The bowler who has released a ball down the alley but continues to behave as if he were controlling it by twisting and turning his arm and shoulder is another case in point. These behaviors have, of course, no real effect upon one's luck or upon a ball half way down an alley, just as in the present case the food would appear as often if the pigeon did nothing–-or, more strictly speaking, did something else.

I wonder if there are even closer examples to Skinner's original, with humans and food. (One from my own life concerns a certain borscht made by a college roommate; I had some just prior to a virulent flu making its appearance and laying me low. To this day, the sight of a beet makes me want to puke.)

There are evil demons abroad. They shape-shift: they visit us in their earthly form as allergies. I don't mean the kind of allergies that send one to the hospital with hives, gasping for breath. I mean the ones we decide are allergies. I mean the superstitious ones.

An early classmate of my son was known as allergic to dairy. It's pretty amazing how much of our food contains milk or butter; this little girl was carefully guarded from all of it. Her teeth had turned brown, but she was otherwise safe. At a birthday party once I was seated next to the mother. Curious, I asked how the allergy had first manifested itself in her daughter. She related how, when her baby was first given solid food--cereal mixed with milk--she developed terrible constipation.

You mean that was it? I wanted to say (but didn't). Because I instantly recalled the constipation that had made my own baby cry after he first ate solid food. In the kind of panic only a new mother can feel--and did, on a daily basis--I raced him again to the doctor. "What can be done for him?" I breathlessly demanded. "Have you ever heard of . . . . prunes?" he asked as if he were talking to a moron. Which he was.

It is not possible for me to count the number of people I know who have gone off wheat. Perhaps many of them suffer from celiac disease. Perhaps many of them do not. All of them report that they feel "better."

We are searching. For safety in a world that, for all its fences and airbags and margins, still feels unsafe. Because we are going to leave it at last. We are right to be frightened, somewhat, of the water, the air, the poisons that seep in and around. But if we can give a name to just one, drawn a cordon around it and banish it forever, we may control all the dangers by proxy. It is superstitious, but it is understandable.

I too want to be washed clean of sin, reborn. But evil hides, swirling in vaporous ether all around. It has no corporeal form; I cannot see it in order to expunge it. Maybe the toast will have to be sacrificed instead. I drive a bullet through its glutenous heart. I feel better already.

*One example, from the dog world, is an unfortunate one: Say a dog is wearing an e-collar because he is enclosed by an invisible fence. He comes too close, gets zapped, just at the moment a child goes by on a bicycle. He imputes a causal relation to the two events, even though there is none. One only has to imagine what might happen the next time a kid on a bike visits the household.

Published on April 16, 2011 06:29

April 9, 2011

Nightworld

Lately I have been trying to catalogue my dreams. In the Dewey Decimal System I have devised, there are only three main categories:

100. - 199.89: I have left my purse, containing wallet, out on a street somewhere and I must get back to it before it's taken, through labyrinthine obstacle courses over great distance accompanied by feelings of increasing panic and hopelessness.

200. - 298.738: I'm on a motorcycle, not mine, or mine strangely configured, with bars too long or too short or made of rubber, or else I am riding through landscapes bizarre and elongated and dark and I don't know if I can get home.

300. - 347.992: houses and more houses. They are either magically grand and out of the pages of Dwell, and they make me think suspicious thoughts like "Finally you have it [slyly spreading smile]. But do you really have it [sinking knowledge it will disappear]?" Or they are like apartments I have in fact inhabited--dark, ugly, dirty, and minuscule--but now underneath or behind closet doors in which appear grand spaces containing swimming pools or velvet-curtained palatial dining rooms that I discover in wonder.

That's it. Three subjects--loss of valuables, loss of way, loss of hopes--but all distilled into one, anxiety.

No one has ever figured out what dreams are really for. What do they represent? Random electric impulses in the brain? A subliminal method of problem-solving? The lost key to the psyche? Hidden meaning, if only you can figure out what the hell they mean?

I recall, as a child, sometimes having dreams of such impossible tastiness, that when I woke I desired nothing but to go back there again. Sometimes I could will myself, in fact, to do so; I had the same dream again. I thought of them as movies I made for myself, that I could play again for myself at will. Then again, sometimes they were so terrifying--running from indistinct figures in the night, or armies of giant robots advancing down the street, never to be escaped--that I would end tied tightly by the bedclothes and sweaty at the foot of the bed, crying for my parents to come save me. They did.

Then, for a period of fifteen years, I had a savage recurrent dream: that someone I loved was going to betray me. I woke sobbing from these nightmares, to be consoled by the actual person who was in the dream. And one day, it happened. In every detail just as it had in the dream.

Was this foreordination? Did it happen because I dreamed it? Or did I dream it because it was bound to happen?

I do not know. I know only that now I have been freed, forever, from those particular dreams. I think, as time goes on, my dreams are in general less imperative; there seem to be fewer of them, anyway. Less vibrant. Perhaps dreams are the products of hormones after all.

But occasionally I still wake from one so strange, and so strangely real, that I write it down. Not for any reason particularly. But reading the account later, I can bring it up in my head again. So perhaps they persist. Perhaps they are all there, all the way back down the years. The dream of charm and happiness you had when you were six is still there. I can in fact remember some of those even though I did not write them down: the epic dreams, the few that were so deeply charged I can still remember: I woke up, in that bed, with that bedspread, with this feeling. Do you remember any of yours?

Dream, night of 12/2/10

I was riding some sort of red sportbike. In my tennis shoes, no jacket or gloves or helmet.

Nelly was with me.

The bike had a set of shelves attached, where a topcase would be.

I parked somewhere, got involved in something occult--I think the place was a train station--and then I heard my phone ringing, but I couldn't answer properly. It was Mark and I heard him saying, "Where are you? If I can't find you, I'm going to head back without you." When I tried to phone him back, I couldn't find the phone function--there were all sorts of other pictures, including Santa, when I opened the phone. No one could help me, so I couldn't reach him.

That's when I realized I would be riding back in the dark, Nelly following, and I felt certain she would be killed on the road at night. I said in bemusement, "This is the first time I've ridden without gear."

Then I was riding down County Route 2. I pulled in at Lynn's house. Dave had made their small fountain pond into a veritable tropical wonderland, and there were all sorts of fantastic creatures mating. [!] Busloads of people started arriving, to have their weddings there. Where'd they hear about it? "Chandra, I guess," said Lynn.

Dreams are the classic case of "I guess you had to be there." Dreams are impulses, emotions, "day residue" (lovely term), images. None cohere with reality, yet are more real than reality. You would have to know things: that Mark and I once got separated when riding in Massachusetts; we had traded bikes, and he had his phone as well as mine, which was in my tankbag, as was my wallet (thank goodness I always carry a credit card in my jacket pocket, because I had to gas up to get back to New York); that Lynn is one of my best friends, someone I think of as a haven, and that her husband Dave is a naturalist and a gardener who can make magic, though perhaps not quite to the extent that I saw in my dream; that buses pulling up to their farmhouse on County Route 2 is beyond strange, and why would I ever dream that; that Chandra is a beautiful friend who moved to Texas but who still exerts a pull on me, and always will; that Nelly is my anxiety as well as my love, and to think of her running down dark roads is the greatest fear of all.

You never know what is there, in the air about you while you sleep, or in the mind, which is always there but made strange in the night. Why. I wonder why.

Published on April 09, 2011 05:08

April 2, 2011

Columbia v. Yale

All the decisions I made in my twenties were well-considered, wise, and based on long-range vision into what I knew my future should bring.

All the decisions I made in my twenties were well-considered, wise, and based on long-range vision into what I knew my future should bring.Yeah. Well, I tried. You too?

What in our evolutionary history made us such Monkey See, Monkey Do creatures in our youths? Is this really necessary? In sixth grade, as I see now in close-up every time my son comes home from school with another stunning tale of kids' inhumanity to kids, children are learning that to be different, to stick out even a quarter of an inch from the edge of the norm, is to invite assassination. No, really. It's a psychic death that is visited on the hapless different, but it plays out in the physical realm: look different, act different, and get ostracized--no one sits with you at lunch; distasteful glances are hurled your way as you are passed by on the playground.

So you learn, very quickly learn, to follow the leader.

I imprinted on my friends, as the gosling does on whatever is near at that tender age that can stand in for mother, and followed them wherever they led. Not that they weren't going to the ideal places, thank goodness. But if they should have decided to head for Sioux City after graduation instead of New York, I suppose I should have followed them there.

Now, the love of literature was something I arrived at all by myself. (Surely it had nothing to do with the fact that my mother was a writer manque or my father declaimed Shakespeare all the time, right.) I got a job in publishing right after college only because I couldn't find one in retail or advertising, but I assume it was my subconscious leading me to where I really ought to have been, so I'll claim this development as my own, too. And falling in love--bam, all in one moment, just as they write about in books--with the new editorial assistant who joined our ranks was another step on my very own, unique path. That he and I wrote poetry obsessively, sending it to one another through inter-office mail (little did the mail boy suspect what was in his silver cart, hidden in dirty yellow envelopes with long series of scratched-out names: typed pages lyrical, yearning, obtuse), was either a happy accident or foreordained by the universe.

But when he decided to go back to school, leave publishing in order to pursue a purer form of living with literature, I regressed. All the way back to the gosling years. I decided I must do exactly the same thing.

Only we were going to be doing it in different cities, because he got into Yale and I didn't. The shame of it--Columbia instead! Too, he had gotten a scholarship while I didn't, which felt like the final insult. Until I started visiting on weekends, and then I got the rest of the slap in the face.

What a lush place Yale was, insulated, warm and providing all. We would sit in the graduate student lounge in blond-wood booths, drinking coffee and discussing hermeneutics with other comp lit students. We would go to the library, and there on the reserve shelves I would find, lined up like steadfast tin soldiers, twelve copies of the book I desperately needed, while Columbia's single copy had been taken out of Butler Library by a faculty member three years before and never replaced. It was tough luck at Columbia. They didn't even have a decent place to sit until all hours discussing imperative b.s. The campus was the most off-putting place I've ever been, and I was always a stranger. I rode the subway two hours a day to be desperately lonely there. And I went ten thousand dollars in debt. I did make one--count 'em, one--friend the whole year. He turned out to be one of the best friends in life I'll ever have, though, so that is not a complaint. Not really.

Yet what I remember most about visiting New Haven has nothing to do with studying. It has to do with place, and the contrast between two places that are as emotively different as two places can be.

Or could this be about how I experienced myself then, always second-best? I will leave that question hanging in the air, and return to the concrete. It is safer there, with ground under the feet.

I remember (even now, remember the look and feel and taste) of the grilled cheese sandwich off the grill at the lunch counter a few blocks off campus. It had not changed since 1946, I think. (The lunch spot, I mean, though this might well be the case with the sandwich, too.) I remember his apartment, white and spare and light-filled, with a rooftop extending out from under one window, where I imagined come summer we would put a couple of lawn chairs and some potted flowers. We did not. I remember the green barette I bought at a little store filled with small objects of luxury and cool, each and every one of which I wanted. The barette surfaces every few years only to go missing again, much like these memories. I remember sitting in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, marveling at the walls of translucent marble through which a milky light seeped. I especially remember walking through Louis Kahn's British art gallery, a building that remains to my mind one of the most perfect examples of the art of architecture I've ever seen.

At the end of the year, I left Columbia. I left the notion of a career in academe forever: perhaps this marked the end of my need to follow others, too. It had not been a well-considered decision, after all. It was probably the competition between Columbia and Yale that convinced me of this. Although maybe if I had gotten in to Yale, the course of my life would have been different. I cannot know that now. Something, I am not sure what, led me out and away. I can only hope I was, and have been ever since, following someone else. Maybe that person is me.

Published on April 02, 2011 08:12

March 26, 2011

Wishful Thinking

What would I give.

What would I give.Sometimes the mind slides an updated picture over what is actually in front of the eye, and so it was yesterday--the day before the snow that is now whitening the view out the window--at the place called Big Deep.

Nelly and I walked through the woods along the creek, following it all the way to the elbow bend where the water is caught in a great cup of rock, and there it collects, deep and green. One perfect giant of a tree is poised at the very edge of this C's midpoint, and on one of its strong arms, held out high over the water as in benediction, a thick rope has been tossed and secured. The big knot tied at the end is the place where bare feet press together, once airborne, then let go when the farthest reach has been attained--and splash. Into the swimming hole that suddenly is before me, a vision of August here in March.

There are dozens and dozens of people here. Towels are spread on the soft dark sand--bequeathed thoughtfully by early-spring floods--under tall pines. Nylon chairs are set in the shallows, and teenage girls cool their heels (and ankles) while chatting at the same time they listen to the radio that sits on top of an ice chest; a multitasking talent of young ladies who could also add painting their nails and making life decisions into the mix without a carefully combed hair escaping their braids. Dogs wade (Nelly looks for unwatched picnics). Children line up for their turn on the rope. It is the community swimming hole 2010, but its pleasures are essentially unchanged from the swimming hole 1910.

The only thing that's different, apart from the portable radios, is the concentration of people. It's ten times greater, because so is our population. But there is a bigger factor: there are vastly fewer swimming holes these days. People are rapidly shutting off access to spots people have been using to battle the summertime heat for generations. Perhaps someone can explain to me what changed somewhere around 1990 to make litigation the number-one threat to what remains of our steadily diminishing commons. There simply had to have been some legislation, or consolidation of power, that got slipped onto the books around then. Someone can explain to me, and then I'll feel simultaneously sad and mad, which is the state into which modern society puts anyone who is awake enough to notice what is being lost.

And so, if you possess any knowledge of a great swimming hole--one that feels practically yours alone--guard it closely. It may be taken, and what then would you do on a long hot summer afternoon?

It has been a few years since I last visited the gem of my private collection of swimming holes (yes, I'll share them, if you are very, very nice to me and/or help work on my motorcycles). It sits at the apex of the crown because it is not one, but rather six, ponds in which to float solitary, swimming among the clouds that have photographically printed themselves on the flat surface of the water. This was as far as the developer got: six gravel drives to six ponds at six homesites. But no homes. And no one around. Oh, and a secondary benefit of disturbing the soil to build those drives: the thickest concentration of blackberry canes in five counties. You can pick quart upon quart in minutes, then sit down by your very own pond--which one shall it be today, dear?--and eat all the berries you can hold before splashing back into the icy cool.

What a freaking Norman Rockwell, eh?

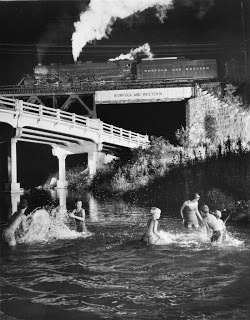

The earliest in my collection was practically literally painted by him, or maybe closer to the physical equivalent of inhabiting a Charles Ives symphony (most probably New England Holidays). My childhood best friend, the daughter of two artists, spent summers at the family farmhouse in Vermont. And sometimes I went there too. For an image to complement the description, refer to the Charles Sheeler photograph previously posted. Shaker austerity. The very paucity of any raucous amusements--mainly, we went outside with our sketch pads, or went blueberry picking up the mountain, or collected fresh fir balsam to stuff sachets, or played Scrabble at night and assembled puzzles when it rained; that was about it--is exactly what made these vacations seem unspeakably rich to my young mind. And then there was the swimming hole. A concrete dam had been built on the brook rolling down the hillside from some cold origin, and the water backed up nine feet deep. We threw ourselves, again and again, screaming at the shock, into the numbing water. I will never forget that time and that place: it is an immersing memory of a private place that seemed there for us alone. The essence of summer, and the fullness of a wet joy. I hope you remember your own. Better yet, I hope you have it still.

photo: O. Winston Link,

"Hawksbill Creek Swimming Hole,

Luray, Virginia," 1956

Published on March 26, 2011 06:59

March 19, 2011

10 Pictures

It is a Palace of Democracy. What is inside was made for kings, pharaohs, generals, dictators, thieves, and the wealthy, who are all of those things. Yet here I was, and now all of it was mine--only temporarily but hey--for the price of a dollar ("Suggested admission: $28" ["Pay what you wish" in type almost too small to see, or that was their hope]). The plunder of nations and the ages, all collected in one lavish, epically scaled building, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I like entering by the grand staircase of what appears to be a thousand steps: one should sweat a little for prizes like these. Into the immense white hall, with its sprays of fresh flowers the size of a football player. (They are replaced once a week, year round, under the terms of an endowment to the museum expressly for this purpose.) The Great Hall functions as a mountain: reminding us how small we are.

This day, we let the two boys, clutching their drawing pads, rush ahead into the Greek wing. They hunkered down on the floor, blending into yet another group of art students, clustered at the feet of ancient heroes, with their offerings of sketchpad and charcoal. I was drawn, not to the heroic, but to the impossible: a small case containing glass. From Rome. Whole, unchipped. It spoke of miracles. Maybe they were small ones, but those are the ones we can grasp.

After the sculpture, the boys intended to visit (of course) the swords. Then the samurai armor; it always frightens me. But them--it makes them dream. Of being frightening. That which the male of our species hopes for, while the female yearns to attract the warrior so he will take off the frightening armor, frightened of her. We wear it in different places, that's all.

The ladies decamped to the more intimate spaces upstairs, to see some photography. I wasn't much interested in the show of Steiglitz, Steichen, Strand--it is hard to see these grandaddies with a fresh eye, just as it is hard to look at the Mona Lisa and see anything but a thousand parodies--but I was interested in a show titled "Our Future Is in the Air: Photographs from the 1910s." It got me thinking of the photographs I love, that always look new to me, and I felt like mounting my own exhibition, an intimate chronology of the art, starting with two from the aforementioned show.

Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Tadeus Langnier

Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Tadeus Langnier

Anton Giulio Bragaglia, The Typist

Anton Giulio Bragaglia, The Typist

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley

Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Bichonnade Leaping

Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Bichonnade Leaping

Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House--the Stove

Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House--the Stove

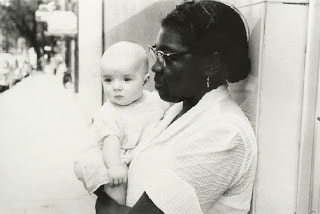

Robert Frank, Charleston, South Carolina

Robert Frank, Charleston, South Carolina

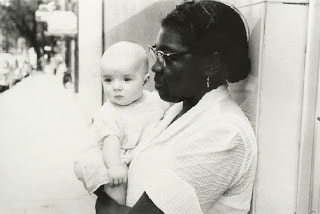

Garry Winogrand, New Mexico

Garry Winogrand, New Mexico

John Pfahl, Trojan Nuclear Power Plant

John Pfahl, Trojan Nuclear Power Plant

Lewis Baltz, from Park City

Lewis Baltz, from Park City

Richard Misrach, Desert Fire #249

I tried to figure out what linked these images, and for a long time I could not--apart from the fact that I love them especially,for they each appear to me nearly perfect. They are from different traditions and visions: futurist, formalist, snapshot, the "ruined landscape," the age of Manifest Destiny. Then I realized: they are all linked by their dedication to surprise, to opening the eye to what has been unseen in what is always seen. They are new, even if they are old.

I like entering by the grand staircase of what appears to be a thousand steps: one should sweat a little for prizes like these. Into the immense white hall, with its sprays of fresh flowers the size of a football player. (They are replaced once a week, year round, under the terms of an endowment to the museum expressly for this purpose.) The Great Hall functions as a mountain: reminding us how small we are.

This day, we let the two boys, clutching their drawing pads, rush ahead into the Greek wing. They hunkered down on the floor, blending into yet another group of art students, clustered at the feet of ancient heroes, with their offerings of sketchpad and charcoal. I was drawn, not to the heroic, but to the impossible: a small case containing glass. From Rome. Whole, unchipped. It spoke of miracles. Maybe they were small ones, but those are the ones we can grasp.

After the sculpture, the boys intended to visit (of course) the swords. Then the samurai armor; it always frightens me. But them--it makes them dream. Of being frightening. That which the male of our species hopes for, while the female yearns to attract the warrior so he will take off the frightening armor, frightened of her. We wear it in different places, that's all.

The ladies decamped to the more intimate spaces upstairs, to see some photography. I wasn't much interested in the show of Steiglitz, Steichen, Strand--it is hard to see these grandaddies with a fresh eye, just as it is hard to look at the Mona Lisa and see anything but a thousand parodies--but I was interested in a show titled "Our Future Is in the Air: Photographs from the 1910s." It got me thinking of the photographs I love, that always look new to me, and I felt like mounting my own exhibition, an intimate chronology of the art, starting with two from the aforementioned show.

Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Tadeus Langnier

Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Tadeus Langnier Anton Giulio Bragaglia, The Typist

Anton Giulio Bragaglia, The Typist Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Bichonnade Leaping

Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Bichonnade Leaping Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House--the Stove

Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House--the Stove Robert Frank, Charleston, South Carolina

Robert Frank, Charleston, South Carolina Garry Winogrand, New Mexico

Garry Winogrand, New Mexico John Pfahl, Trojan Nuclear Power Plant

John Pfahl, Trojan Nuclear Power Plant Lewis Baltz, from Park City

Lewis Baltz, from Park City

Richard Misrach, Desert Fire #249

I tried to figure out what linked these images, and for a long time I could not--apart from the fact that I love them especially,for they each appear to me nearly perfect. They are from different traditions and visions: futurist, formalist, snapshot, the "ruined landscape," the age of Manifest Destiny. Then I realized: they are all linked by their dedication to surprise, to opening the eye to what has been unseen in what is always seen. They are new, even if they are old.

Published on March 19, 2011 04:27

March 12, 2011

Genesis

I had it; now I had to make it mine. That is, I had to get it registered--in New Jersey, the state that presents its problems.

I had it; now I had to make it mine. That is, I had to get it registered--in New Jersey, the state that presents its problems.The first was figuring out how to break into a closed circle, viciously constructed of sticky red tape: I could not ride it until I was licensed, and I could not get licensed until it was registered, and it could not get registered until it was inspected. By someone riding it with a license. This is where strangers on the street come in.

I saw someone down the block leaning over a motorcycle. Desperation is good medicine for shyness. I approached.

Sure! He'd be happy to take it for inspection. His buddy would follow, driving me in his car. That is how I came to be sitting on a Saturday morning at the inspection station behind my new old motorcycle, watching in growing agitation as we . . . sat there. And sat. (New Jersey, Land of the Eternal Wait.) I realized that the fellow did not know, or appreciate, the fact that this was an air-cooled machine, and idling in the close summer air was cooling exactly nothing. After a while, fighting with my impulse to not upset the boat, to not second-guess people who obviously knew better (A Man! And a Man Who Owned a Motorcycle!), my compassion for this poor machine finally propelled me like a nine-foot wave. I ran over to him. Huh? he says. Oh. Okay. And turned it off.

Later I learned it just as easily might not have started again for a long while, after such abuse. But it was a V50, my V50, and it was endlessly forgiving. It was a stalwart machine. A forever machine.

And that is how I came to be riding it through the Holland Tunnel of an evening. (When the traffic was at a standstill, I lane split, illegal though it was, reciting in my mind all the while the little speech about the needs of an air-cooled engine--never mind the rider's need for oxygen--I would give to the sympathetic gendarme.) I was heading downtown, the site of all hope and life and desire in the early eighties, in one's middle twenties.

First there would be dinner at the place in Tribeca whose name I have forgotten, along with the food. (That was forgotten about three minutes after it was eaten.) The notable thing about the place was that it may well have been the last place in New York City where artists were permitted to run a tab--a long tab. The walls were hung with paintings from those whose tabs were left open a little too long. No matter; they paid up one way or the other.

I parked on the sidewalk; that is what we did then, in the era of many latitudes. We did what made sense, in that age before parking infractions became municipal big business. The cops had better things to do. Especially in the depopulated nether regions of the city, the places where after 5 the streets were left to those relative few of us simply wandering in our search for our own kind in the dark.

After dinner I went back out, pulling on my helmet as I went. And stopped, when I saw something had been left on my seat.

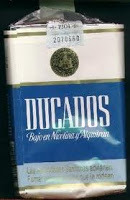

A half-filled pack of cigarettes, of a type I had never seen: Ducados. At a time when everything was taken as a sign, a swirling mystery (that music--is it speaking to me alone? that boy--could he be the one? ), this was a mystery indeed, and one that filled me with a shivering. Did someone know I was still yearning for the departed lover, the one who rode Ducatis?

A half-filled pack of cigarettes, of a type I had never seen: Ducados. At a time when everything was taken as a sign, a swirling mystery (that music--is it speaking to me alone? that boy--could he be the one? ), this was a mystery indeed, and one that filled me with a shivering. Did someone know I was still yearning for the departed lover, the one who rode Ducatis?It took me years to realize that (duh) someone passing by had simply stopped to light a smoke, perhaps chatting with a pal and using my bike as a coffee table. But this night, it had meaning. Like every vision, every minute, in New York City when every wish had yet to be fulfilled, and might be--in the very next moment.

All these memories come raining back as I read Patti Smith's Just Kids, her memoir of her life as a beginning artist in a milieu that was a stewpot for a creative soup, in this very locale only a decade before I came to it. I ate in the same places, walked the same streets, shopped the same stores. The city welcomed the hopeful, and rewarded them with food to eat: psychic food, and on occasion actual sustenance (I, too, often visited Nathan's in Coney Island, where she and Mapplethorpe ended after their ride on the F train).

I found out about a nightclub I was told I would be welcomed to, in this era of the forbidding velvet rope and stone-countenanced bouncer, so long as I arrived on a motorcycle. What luck! I had one! The proprietor was said to be a collector.

That is how I ended up at an unmarked door on an alley downtown, on St. John's Lane, between Canal and Beach. (Was it another sign that, ten years later, I would find myself living on a street named St. John's Place?) The heavy velvet curtain inside the door parted, and I was in Madame Rosa's, where DJs played the most amazing, previously unamalgamated, infectiously danceable music I'd ever heard in my life. I went there every chance I got, parking the Guzzi in a line of other unusual motorcycles. Then something happened, I don't remember what. The time of Madame Rosa's came to an end. The Mudd Club, CBGB, came to an end. The unnamed restaurant came to an end. Robert Mapplethorpe came to an end; Patti Smith is in her sixties. The time of the V50 came to an end. The New York City I knew came to a crashing, shuddering end. Youth, too.

How often I am startled by my own past, when I chance to walk past it, now preserved in their own discrete vitrines. Later (I must remember) what happens even now will still later appear to me, behind glass, with informative wall tags. I must remember.

It was only later that I realized there was more to come, an endless string like pearls. Nothing, yet, has come to an end. I am tired of sadness. There will be more to come. (Except the nauseousness of getting groped in crowded subway cars; those days really are gone.) So it is that memories still live, still re-form. The necklace adds to its length. I called this "Genesis." What comes to an end comes to an and.

Published on March 12, 2011 06:54

Melissa Holbrook Pierson's Blog

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson's profile

- 19 followers

Melissa Holbrook Pierson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.