Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2253

July 5, 2011

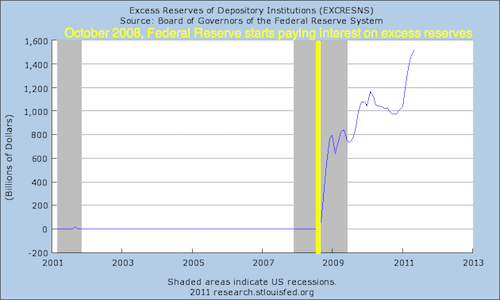

Interest Payments On Excess Reserves

A bank, as you may know, doesn't actually hold on to the money that people deposit in it. Banks lend the money out. But they're not allowed to lend all the money out. They have to hold some in reserve, and the quantity of money they need to hold is set by regulators. A bank, however, always might want to hold even more money in reserve. But if you look at history, it's clear that American banks have never had any interest in holding on to so-called "excess reserves" until in the fall of 2008, the Federal Reserve started paying a small amount of interest on such reserves:

The stated reason for this policy makes very little sense to be. Allegedly, Ben Bernanke started paying interest on excess reserves in order to signal that in the future he might pay even more interest on excess reserves in order to soak up excess liquidity in case we end up with an inflation problem. But why does he need to pay a small amount of interest now in order to be able to pay a large amount of interest later? The underlying point of the interest on excess reserves policy is that such interest payments are contractionary. And at the moment the Fed is supposed to be engaging in expansionary policy. Why not go back to the long-settled tradition of paying zero percent interest? Why not pay attention to Sweden's success in setting this as a negative number? Alternatively, if the view is that a giant increase in bank reserves is desirable (it makes the system safer, whatever) why not raise the required reserve level?

No, We Don't Need Israel As Much As Israel Needs Us

Once upon a time, Israel presented itself in the American political discourse with some plausibility as a kind of charity case. Under modern circumstances, that makes no sense. Israel is a high-income country with the strongest military in its region and an arsenal of nuclear weapons that secure it from conventional attack. Israel is a democracy with a claim on our sympathies, but countries from Brazil to Mexico to India to South Africa all suggest themselves as democracies with much more in the way of objective material needs. But no political movement lives on raw congressional power alone, so the advocates for heavy U.S. subsidization of Israel are increasingly turning to a preposterous rhetoric in which said subsidization is actually beneficial to American citizens rather than an act of charity. Hence Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's ridiculous though much-applauded claim that "America has no better friend than Israel."

Today in the Wall Street Journal, George Gilder of the Discovery Institute takes a break from peddling creationism to argue, "We need Israel as much as it needs us." The argument here is that Israel makes some high-tech goods:

Israelis supply Intel with many of its advanced microprocessors, from the Pentium and Sandbridge, to the Atom and Centrino. Israeli companies endow Cisco with new core router designs and real-time programmable network processors for its next-generation systems. They supply Apple with robust miniaturized solid state memory systems for its iPhones, iPods and iPads, and Microsoft with critical user interface designs for the OS7 product line and the Kinect gaming motion-sensor interface, the fastest rising consumer electronic product in history.

It's quite true that Israel's high-tech cluster is an impressive achievement, and it plays an important role in a globally integrated economy. But in an era of global supply chains, American technology firms obtain components from all kinds of places — China, Taiwan, Korea, etc. — and nobody's suggesting that the United States ought to subsidize any of those other countries at anything remotely approaching the Israeli rate. More to the point, this form of argument seems to miss the entire point of commerce and gains from trade. The consumer surplus from Israeli technology products is available to customers in Canada and New Zealand and Peru and Botswana just as much as it is to Americans. We're not deriving any special benefit from Israel-based firms in light of our relationship with Israel.

Indeed, I'd say serious examination of Israel's commercial and economic success militates in the opposite direction. It underscores the reality that Israel is a strong and prosperous state that has no particular need of American assistance. Nor does it have any particular need for land in the West Bank or military control over the Jordan Valley. Instead, a very successful society's long-term viability is severely threatened by its insistence on trying to govern a population of millions of non-citizens.

July 4, 2011

The Most Overpaid Players In The NBA

Two of the top five are Gilbert Arenas and Antawn Jamison, both recipients of unjustifiable contracts from the Washington Wizards a few years ago during a period of bizarre management over-confidence in what was, at the time, a totally mediocre team.

Bicycle Commuting Fact Of The Day

Courtesy of an excellent Nancy Folbre post:

Increased bicycle use is practical and feasible, especially if it can be combined with effective public transportation for long-distance needs. As John Pucher of Rutgers University (dubbed Professor Bicycle by some of his fans) explains, about 40 percent of all automobile trips in metropolitan areas are less than two miles – a distance easily biked.

I will say that I think the current trend in cycling policy in the United States somewhat tends to overemphasize things like bicycle lanes. It seems to me that if cities acting to remove subsidies and mandate for automobile parking, that this would on its own do a huge amount to spur people to rely more on bikes for appropriate trips triggering the all-important safety in numbers phenomenon. Naturally if lots of people are riding bikes around your city, you should make some lanes. But I think that's a secondary issue.

Beijing-Shanghai Bullet Train Opens

I missed that this actually happened earlier this weekend: "The fast link, which has been hit by safety concerns and graft, is opening a year ahead of schedule and will be able to carry 80 million passengers a year — double the current capacity on the 1,318-kilometre (820-mile) route."

Safety concerns and graft are all well and good, but the fact of the matter is that they built a 820-mile train route in a little bit over three years. It connects two of the world's top twenty cities, and it goes 190 miles per hour (they hope to get that up to 220). The trip will take five and a half hours. And the intermediate stops aren't slouches. Tianjin, Jinan, Xuxhou, and Nanjing are all cities of over 2 million people.

Discretionary Fiscal Stimulus Has A Big Problem

John Taylor has an analysis of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act which shows that ARRA didn't actually lead to a substantial increase in government purchases and therefore failed to do a huge amount to boost GDP. He concludes:

More generally, the results from the 2000s experience raise considerable doubts about the efficacy of temporary discretionary countercyclical fiscal policy in practice. In this regard the experience with the stimulus packages of the 2000s adds more weight to the position reached more than 30 years ago by Lucas and Sargent (1978) and Gramlich (1978, 1979).

Paul Krugman and Noah Smith both rightly critique the last sentence here. Per Smith, "Lucas, Sargent, etc. thought that government purchases wouldn't raise GDP" which is the reverse of Taylor's conclusion. ARRA didn't boost GDP because a temporary boost in government purchases won't boost GDP, and ARRA didn't boost GDP because it didn't lead to an increase in government purchases are incompatible positions. They're just both criticisms of ARRA and therefore perhaps emotionally satisfying to people who dislike Barack Obama.

That said, I really do think Keynesians need to pay more to Taylor's first quoted sentence here. It seems clear that, in practice, we cannot and should not count on discretionary fiscal stimulus to be the centerpiece of our stabilization strategy in the event of short-term nominal interest rates hitting zero. The case that engineering a dramatic, rapid temporary run-up in government purchases would be a good way of responding to a downturn seems to me to be fairly solid. It's much less clear to me that such a thing is doable in a Madisonian political system that features a large level of partisan disagreement about the appropriate size and scope of the government. We need to work on improved "automatic stabilizers," we ought to be targeting a higher level of inflation so that hitting zero is less likely, and we need to explore the unorthodox monetary tools.

Political Heroes

A July 4 question from Jonathan Bernstein: "Who are your great American (political) heroes? I'll take anything — those who you think are obvious but deserving, those who are obscure but shouldn't be, past or present, whatever."

To start with the obvious-but-deserving, the longer world history rolls on the more remarkable George Washington's peaceful assumption of power and departure from office looks. I believe the current understanding is that he did this in part out of a motivation to be remembered as a Great and Honorable Man by history, so it's worth paying tribute to him if for no other reason than to try to inspire other powerful people around the world to consider the option that doing the right thing may be your best strategy.

Philip Randolph strikes me as an underrated player in the history of the civil rights movement. The tendency is to celebrate the people who played the biggest roles in getting the ball into the end zone, but in some ways the achievement of the activist leaders of the 30s and 40s who actually changed the trajectory of policy after several decades of continued advances for white supremacy are even more impressive. Also as union leader and a socialist and important reminder that on a correct understanding of human justice the idea of a sharp disjoint between "social" and "economic" concerns is badly misguided. In a related way, the "Radical Republicans" of the 1860s and 1870s were, at a minimum, hideously underrated by my high school history textbook. I'll single out Thaddeus Stevens for, among other things, offering a useful manifesto for radicalism in general—"Prejudices may be shocked, weak minds startled, weak nerves may tremble, but they must hear and adopt it: Universal emancipation must be proclaimed to all." Frances Perkins is incredibly impressive as someone who wasn't just a pioneer for women in public life but also as a pioneering woman in public life stands out as one of the major architects of the American welfare state.

Last, let me offer up Gouverneur Morris a man of considerable merits who I want to recognize specifically for his role in the Erie Canal. People don't generally recognize that New York City wasn't simply fated to become the nation's largest. Its status as the East Coast's largest seaport, and therefore largest city, is pretty purely a consequence of the fact that this gigantic infrastructure project was undertaken which suddenly made its port much more valuable than those at Baltimore, Philadelphia, or Boston. There's a tendency in modern America—a tendency that I find vaguely un-American, to use an ugly term—to simply refuse to dream big and believe that large change for the better is possible. Morris and the canal from the Hudson to the Great Lakes are the antidote to that. The canal opened in 1825 and now almost 200 years later the consequences of that achievement have still not been undone.

Independence Day

There's something remarkably—and appealingly—liberal, universalistic, and cosmopolitan about the Declaration of Independence whose signing is commemorated by our national holiday.

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed.

July 3, 2011

Jobs And Transportation

Tanya Snyder wonders if it really makes sense to be touting the short-term employment impact of investing in transportation infrastructure. After all, the real benefit here is that over the long term better infrastructure leads to more growth and higher quality of life.

I think that's right, but I do think the jobs point is relevant. After all, any time someone comes along with a proposal to build a train line or repair a bridge someone is going to be concerned that the project is wasteful. At this point, you have to ask yourself what, exactly, is it that we might be wasting. "Money" is often the answer you get, but while individual government agencies do have fixed budget constraints, the United States as a whole is at no risk of running out of dollars. The thing that might be wasteful about increased transportation infrastructure investments is real resources. Human labor, steel, concrete, building equipment. These are things that could be used on some government-funded pet project, or could be used on projects that the private market has deemed to be sound investments. But how much we worry about this ought to be in large part a function of how many idle resources we have. In October of 2000, the unemployment rate was 4 percent and the employment:population ratio was the highest it had ever been in American history. Under those circumstances, before you pull real resources out of the private sector you want to be very sure you're doing something worthwhile. When it's June 2003 and the unemployment rate is 6.2 percent you're looking at a very different situation. And when it's May 2011 and the unemployment rate has been consistently over 9 percent for two years then you're looking at a very different situation. The United States is not running short on construction workers. Useful projects are, as always, better than useless ones but with this quantity of idle real resources the bar something needs to cross to be worth doing is extremely low.

Again: What's The Case For Sameness?

I'm once again struck by the extent to which legal regimes embed the notion that sameness, as such, is a value worth preserving. Here's Kelly Matlock reporting on a proposed development that would replace a vacant lot that's inside a historic district:

In her testimony to the HPRB yesterday, Green stated, "The Takoma Central District Plan specifically addresses height. It states that 'new commercial and residential buildings should be no more than 2-4 stories in height to match existing residential scale' and to preserve Takoma's 'small/town village character'."

She continued by saying that, "The Takoma Overlay District permits heights of up to 55 feet, but as I also understand it, you have the ability to reduce the height, as needed, on case-by-case basis."

Note, again, that we're not talking about knocking down a historic structure and replacing it with a new one. We're talking about replacing a vacant lot. Yes, it's a vacant lot in a historic district. But it's a vacant lot. And we're being urged by members of the community to restrict the size of the new development—a move that has citywide implications for housing affordability, the tax base, etc.—in order "to match existing residential scale." Obviously, though, no neighborhood as it currently exists could have been built if not for the fact that at some point in the past new structures weren't erected that failed to match what existed previously. And it's not at all clear to me why we would think it's the case that, as a rule, conformity is an important aesthetic value that needs to be balanced against other economic and environmental considerations. If someone was objecting to a proposed new building on the grounds that it's ugly well then that would make perfect sense. Nobody wants to see something they think is ugly go up across the street. But the problem with the new building is just that it's not the same as other buildings nearby? Who cares?

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers