Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2256

July 1, 2011

Andrew Cuomo And The Class War

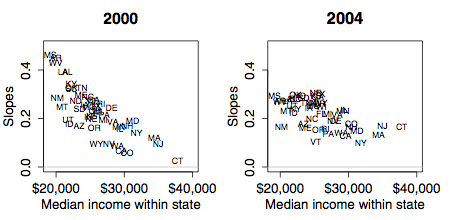

Eric Alterman did a pointed Daily Beast column last week on Andrew Cuomo's flawed liberalism, noting that the hero of the fight for marriage equality isn't much of a hero of the class war. I think that to understand the way in which this does and doesn't reflect the overall national political trend, it's useful to go back to Gelman, Shor, Bafumi, and Park's 2007 article "Rich State, Poor State, Red State, Blue State: What's the Matter with Connecticut?" (PDF). The basic findings of this research are as follows. One is that voting patterns, viewed nationwide, are polarized along income lines. Richer people are more likely to vote Republican. But rich states are more likely to vote Democratic. What's more, voting behavior is starkly income polarized in poor states, but only very weakly polarized in rich ones.

Here's a quick summary:

What you see here is that the political behavior of voters in states like New Jersey, Connecticut, and New York has very little linkage with income. Voters in these states are largely basing their decisions on other factors, such as gay marriage. By contrast, in a state like West Virginia or New Mexico, voting behavior seems much more strongly correlated with income. This means we might expect state politics to look very different from place to place, and for New York politics to be much more polarized around "cultural" issues than overall national politics is. National politics, by contrast, features a kind of schizophrenia. On the level of voters national politics is strongly income-linked and Barack Obama leads a political coalition based in overlapping categories of African-Americans, Latinos, single women, and young people all of whom tend to have relatively low incomes. But on the level of fundraising the primary dimension of conflict looks more like the politics of New York where the parties are clashing primarily over social issues.

Today's Patent Wars News

Further adventures in America's dynamic, entrepreneurial free market economy:

News that Google had competition for a bundle of patents being sold by bankrupt Nortel Networks surfaced a week ago, and now it's official; a consortium of companies including Apple, EMC, Ericsson, Microsoft, RIM, and Sony won the multi-day auction with a bid of $4.5 billion. According to Reuters, RIM contributed $770 million to the effort while Ericsson is on the hook for $340 million when the deal closes, which is expected to be in the third quarter of this year. What they'll do with the over 6,000 patents and patent applications covering everything from wireless to optical to semiconductors isn't immediately clear, but what won't happen is Google using them as leverage to stave off the patent-trolling hordes.

I think the basic dynamic to keep in mind here is that insofar as rich high tech companies dedicate resources to hiring engineers to compete with one another buy building better products, the consumer ends up winning. But insofar as rich high tech companies dedicate resources to hiring patent lawyers to sue each other or hire investment bankers to help evaluate patent-based acquisition strategies, almost all the surplus is accruing to the lawyers and bankers.

Heritage Foundation Refusing To Admit It Made A Mistake On Tax Preference For Corporate Jets

Both the corporate income tax and the question of accelerated depreciation for capital goods are complicated subjects. So it's no surprise to me that when President Obama was making some remarks about his desire to close a tax-subsidy for corporate jets, people at the Heritage Foundation disposed to be unkind to him misunderstood what he was talking about and confused the provision in question with a 2008 "bonus depreciation" tax provision that was extended by the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. What's remarkable, however, is that with the error pointed out, Heritage is digging in its heels and acting snide at those of us who are trying to point out the truth.

But to review. In 2008, the economy was sliding into a recession and there was agreement between President Bush and Congress about the need for some economic stimulus. One of the things they did was a "bonus depreciation" for corporate purchases of capital goods, including aircraft. The aviation industry got some kind of special treatment for aircraft — both corporate and commercial — put into that. Then this provision was extended by ARRA. But like other stimulus measures it's set to expire and has no impact on the long-term budget situation.

The White House proposal is about something different, specifically a 1987 provision of the permanent tax code that allows corporate jets to be depreciated on a five-year schedule rather than the seven-year schedule allowed for commercial planes. This tax preference for corporate jets is expected to cost the Treasury about $3 billion over the next 10 years, which, as Brian Beutler points out, is really small change in the scheme of things. But a billion here and a billion there and pretty soon you're talking about real money. What's more, this is a permanent provision of the tax code, so even though the impact is small, it's constant. Last, this is a classic example of the economic problem with tax loopholes. If the tax treatment of corporate jets and commercial jets were equal, firms would spend some money on corporate jets and some money on commercial airfare for their executives. Whatever that allocation is would roughly approximate an efficient use of the aviation resources available to society. When you add a provision making the tax code more favorable to corporate jets, not only does the government lose some revenue, but at the margin, you encourage firms to under-invest in commercial airfare and over-invest in corporate jets relative to what would be an economically optimal allocation of planes.

Israeli Opposition To A Palestinian State

It seems to me that it continues to be very poorly understood in the United States that the stated position of the current Israeli government is to refuse in principle to countenance the creation of an independent Republic of Palestine. You get a certain amount of double-talk from the Netanyahu government about this, but Vice Premier and Strategic Affairs Minister Moshe Ya'alon makes it perfectly clear in an interview Gershom Gorenberg conducted for an article in The American Prospect:

He puts much less confidence in diplomacy with the Palestinians. The lesson of the 18 years since Oslo, [Moshe] Ya'alon says, is "that we don't have a partner willing to reach an end to the conflict." So before negotiating final-status issues, he says, the Netanyahu government wants answers from the Palestinians on whether they are willing to recognize Israel "as the nation-state of the Jewish people," whether they'll agree to an end to all claims against Israel, and whether they will meet Israel's security needs. Those needs, he indicates, include Israeli control of the border between the West Bank and Jordan. After Israel left Gaza, he notes, Iranian arms began pouring in across the border from Egypt. In short, what appears from Ya'alon's office at the Defense Ministry as the most pragmatic precondition for Palestinian independence means denying what Palestinians see as a basic quality of statehood: sovereignty over their own borders.

You can deem the security concerns expressed here reasonable or unreasonable as you like. But if Brazil controlled Paraguay's border with Argentina, Paraguay wouldn't be a real independent country. It would be a kind of colony or protectorate of Brazil's.

Now note this earlier point about the political economy of occupation:

Starting light industries in Area A or B is possible, Azzeh says, but "let's say you want to [set up] a pharmaceutical company—you will have problems importing chemicals" defined by Israel as "dual use"—capable of serving as weapons as well as medicine. If you buy a $5 million machine from China, he says, you'll need Israeli permission for an expert to come show you how to use it. To those difficulties, one can add the need to export via Israel. The bottom line is, in Azzeh's words, "I don't have sovereignty over my borders."

In the grand scheme of things, the Israeli government making trade policy with regard to the economic and security concerns of Israeli citizens is hardly the greatest crime in human history. Indeed, how else is the Israeli government — accountable as it is to the Israeli electorate — supposed to behave? But the proposal for Ya'alon is to perpetuate this situation indefinitely, even after the alleged Palestinian state is created. The exact same problem would, however, arise. If Palestinian exports and imports are subject to the control of a government that's accountable to Israelis and not accountable to Palestinians, then there's no way for Palestine to develop economically. This kind of issue lacks the emotional punch of quasi-theological disputes over who has control over which patches of Jerusalem, but in practical terms it represents a gaping void between Palestinian interests and Israeli negotiating positions.

Looking For New Parties Is Asking The Wrong Question On Centrism

I read on Twitter a number of accounts of Aspen Ideas Festival attendees bemoaning the partisanship and extremism in Washington, and yearning for some kind of centrist third party.

There's a lot that's wrong with this, but I think the starting point of wisdom on this score is that you need to ask yourself why the current system doesn't produce centrist policy outcomes. After all, we already have the bicameralism thing, the supermajority voting in the Senate thing, and the presidential veto thing. What's more, though it's true many elected officials don't represent electorally competitive districts, it's also true that the members of Congress near median do face competitive elections. So you have a system that's set up to generally demand compromise between the political parties, and that features pivotal members who have incentives to care about the median voter.

Now of course this does get you a lot of centrist policy outcomes if by "centrist" you mean "nothing changes." But the same features of the system that lead to a tendency toward stasis also lead toward a tendency toward tactical extremism. Everyone is obsessed with negotiating strategy and the Overton Window. If you want politicians to act differently, you'd need them to be operating in some kind of different institutional context. Stephen Harper spent a large share of his re-election campaign trying to reassure Canadians that a Conservative majority wouldn't lead to the implementation of an American-style for-profit health insurance system. I don't think that's because Harper has radically different fundamental views about health care policy from your average U.S. Republican nearly so much as it is that the very lack of checks on a Canadian parliamentary majority make candidates very eager to avoid frightening the electorate.

Breakfast Links: July 1, 2011

— No trial for me, so back to work.

— The idea of Shia LaBeouf.

— Tim Geithner reads the 14th Amendment's public debt clause.

— Sheila Bair wants that debt ceiling chicken is "a dangerous game."

— Thaddeus McCotter (who?) to announce GOP presidential bid.

— Brookland NIMBYs win a round.

— This appears to be someone floating Jamie Dimon as Treasury Secretary.

— Fast food chains looking to alcohol sales to boost revenue.

— Recommended McDonalds wine pairings.

— Chinese factory production slowing.

June 30, 2011

Making Cheaper Health Care Sound Good

Sarah Laskow says for some much-cheaper not-quite-as-good health care pointing that doing so could help her afford more health care overall. Currently, what with regular trips to the eye doctor, an OB-GYN, and a dermatologist for melanoma checks she's not inclined to spend money on seeing a GP. But if something like MelaFind made it possible for a general practitioner to quickly and cheaply do a pretty good melanoma check then three doctors' visits worth of money would be getting her a larger actual quantity of health care services.

That seems like the right way to frame it for the public rather than my provocative claim about the virtues of "slightly worse but much cheaper" health care. What we'd really be looking at is specific instances of slightly worse but much cheaper health care in order to allow for the consumption of more health care services overall within a fixed budget constraint.

Still, my question about whether "we" really want cheaper health care speaks more to the collective choice aspect of things. Any time anything new and innovative comes along that can do something more efficiently than what comes before, some people will mobilize to try to block it. And the health care sector features a lot of safety regulations for obvious and perfectly sound reasons. But insofar as "this new thing isn't really as good as what came before" counts as a valid objection, then the forward tide of efficiency can generally be stopped. Early movies didn't have color or sound but that didn't stop them from coming onto the market, improving, and eventually displacing live theater as the main form of dramatic entertainment. But that's entertainment. We're much more risk-averse with health care decisions for reasons that are, again, obvious and reasonable. Nobody dies from a bad movie. But these are the kind of things that have to happen for efficiencies to develop.

Government By Lottery

One thing that occurs to me on this jury duty day is that I think there's a decent case to be made that we ought to rely on lotteries more as a tool of governance. There's an obvious appeal to something like town meeting direct democracy, but also some obvious logistical problems with it. The main alternative we've come up with is representative democracy, where you vote for some folks to serve as a legislature on your behalf. This has a lot of virtues and I by no means think can or should be dispensed with entirely. But it also does have its limits and problems, and isn't in any obvious way "fairer" than selecting representatives at random.

There seem to me to be plenty of municipalities across America that are too big for town meetings, but still sufficiently rinky dink that they don't want full time professional legislatures. Many of these places already use a council-manager system of government where the idea is for day-to-day running of the city to be in the hands of a hired professional team, with the legislature just serving as a kind of generic check and authorizing tool. In those cases, wouldn't a legislature chosen by lottery make a certain amount of sense? The city manager would basically run the city, and the council wouldn't do much other than approve budgets and if necessary fire the manager and hire a new one. It seems to me that it would work fine, and be actually fairer and more democratic than the current practice.

I suppose this is a solution in search of a problem, but America in general seems to me to suffer from a kind of weird elections-mania and I'm always looking for opportunities to serve democratic values without all this constant proliferation of campaigning.

The Elusive Quest For Enduring Cool

Having poked around Google + for a bit over the past 12 hours, I'm now more than ever convinced of a modified version of a thesis my friend Tom Lee laid out a while ago—we're probably fated to endless cycling through different social networking applications.

I think the underlying issue here was actually laid out extremely well in The Social Network and then ignored in the ensuing discussion of the film. But the movie has Mark Zuckerberg repeatedly emphasize that what makes Facebook an appealing product is that it's "cool" and "exclusive" and they shouldn't ruin it by making it uncool. At the same time, Zuckerberg wants Facebook to be successful. And the only way to succeed over time is to expand. But the more you expand, the less exclusive you become. And the more successful you become, the more lawsuits you get embroiled with. Sitting around a conference table watching your fancy lawyers talk to some other guy's fancy lawyers isn't cool. Getting a status update from your mom isn't cool. Sitting through a meeting at work about your company's Facebook strategy isn't cool. When I first used Twitter, it seemed cool. When the first group of politicians started using Twitter, it was clear that Twitter wasn't actually cool. But those politicians were at least cooler than your average politician. But once it becomes expected that politicians will be on Twitter, there's nothing cool about it. Joe Lieberman having a staffer write on his behalf that "As we prepare to celebrate Jul. 4, Gen. Petraeus' life and leadership remind us that America is still a land of heroes" is incredibly uncool.

So whether it's Google+ or something else, people will naturally end up gravitating toward some new thing. Not because it's "better" in any clear way, but because it's different in some ways and just cooler and more exclusive. At least at the beginning.

Even A Debt Ceiling Deal Has Bad Implications For The Longer Term

Ezra Klein isn't excited about the prospects of President Obama simply sweeping the debt ceiling aside and claiming that imposing legal limits on the government's ability to issue bonds is unconstitutional.

"The market hasn't been caught by surprise and forced to dramatically reassess its confidence that this will ultimately be resolved," he writes, so "now's not the time to overturn the chess board."

Jon Chait disagrees but agrees:

Now? Who said anything about now? I think Obama should try the Constitutional/Zeitlin Option if we're approaching the debt ceiling and there's no deal — i.e., in circumstances when we'd be looking at a bond market freakout anyway.

That's fine as far as it goes, but I do think it's worth dwelling on the dire long-term implications of reaching any kind of compromise on this issue. Historically, the debt ceiling vote has been pure kabuki, an opportunity for opposition party politicians to say mean things about the incumbent president. That's what Barack Obama was doing when he voted against the debt ceiling. He wasn't trying to get President Bush to do anything, he was just seizing the chance to do some grandstanding. John Boehner's notion that there should be actual policy concessions is a game-changer, and any compromise that's agreed to at this point will legitimize Boehner's move.

Once that happens, we're really in a lot of trouble. It's one thing to play chicken with your friend once. But the debt ceiling is an issue that keeps coming up again and again and again. And once it transforms from a meaningless bit of political theater into a high-stakes game of chicken, we really only have three options. Either at some point congress will do the right thing and scrap the idea, or else the country will enter some form of default, or else some president will exercise the constitutional option. Note that thanks to the intersection of the debt ceiling with the filibuster, the kind of hostage-taking that's currently being legitimated can occur in all kinds of political climates. As it happens, nobody's ever tried to filibuster a debt ceiling increase. But that's because nobody's previously made a serious effort to use the debt ceiling to extract policy concessions. Once it turns out that you can get concessions, there's no reason to expect hostage-taking to be limited to legislative majorities.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers