Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2254

July 3, 2011

Movies I've Seen This Weekend

— Transformers 3: Clearly the best of the Transformers films, but if invading alien robots are using Chicago as a base from which to destroy the entire planet I think the appropriate response is going to be a nuclear strike on Chicago. That said, I was impressed by Michael Bay's vision of Washington, DC as a city full of skyscrapers and tall buildings with sufficient housing supply that a young couple can afford an awesome duplex loft. Well done.

— Midnight in Paris: Maybe it's just me, but I found myself persistently irritated by the fact that nobody has a cell phone. Maybe that's because they're all Verizon customers or have turned their international data roaming off, but even so for years now when I've traveled abroad there's frequent discussion from the suddenly device-less about how disconcerting this is. On the other hand, it's a movie about nostalgia so….

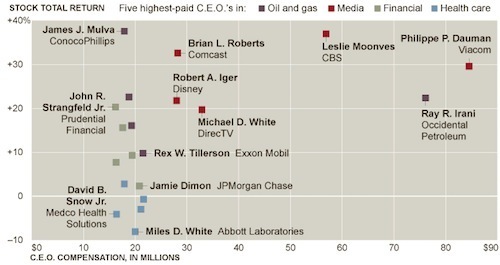

CEO Pay Rose 23 Percent Last Year

The NYT has a bunch of interesting charts on this. But suffice it to say that high-level managers appear to have become much more skilled at directed value into their own pockets:

What I always wish I could see more of were direct international comparisons. Not only do high-paid oil and gas CEOs all get paid roughly similar amounts of money despite drastically different performances, but running a large American oil company is much more lucrative than running the giant French oil company. Anglophone firms just pay CEOs much more than continental European firms or Japanese firms. Meanwhile, though pretty much all firms are happy to discover and apply some new methods to hold down labor costs you rarely if ever see a firm bragging about its success in reducing executive compensation.

Poverty And Indigenous Cultural Preservation In Oaxaca

Mexico is a somewhat above-average country in terms of per capita GDP, but that average figure masks huge disparities. When I went to southern Mexico last December it was clear that outside of the central city of Oaxaca you were looking at a very poor area dominated by low-productivity agricultural activities and traditional crafts. But as an interesting Guardian piece observes, there's a tension between aspirations for development and aspirations for cultural integrity and preservation:

Elena Gonzales folds yarn between her fingers. Her tapestry is woven in an intricate pattern of ochre and indigo, with fibre that has been dyed using moss and bark, fruit and flowers. Here in the hills of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, indigenous Zapotec communities have been weaving rugs for more than two thousand years. Elena spins the loom and the centuries fall away.

Like many Zapotec children growing up in the 1980s, Elena did not attend school. Faced with a primary curriculum that took no account of Zapotec language or culture, her parents decided that she should be educated by her community. She was taught to weave by her grandmother. Self-sufficiency is the historic norm in Oaxaca, but in recent decades as rural life has become increasingly entretejidos – interwoven – with the modern market economy, Zapotec children who have not gone to school are finding themselves on the wrong side of an urban-rural education divide that excludes them from employment and contributes to deepening poverty.

Obviously, the dilemma here is real. Not only does formal education improve one's earning potential, so does better transportation and communications connections to the outside world. And Spanish-language competence has a higher market value than Zapotec-language competence. So insofar as you put an overwhelming premium on cultural preservation, the tendency will be for that agenda to entrench poverty. After all, the authentic cultural tradition of indigenous peoples in southern Mexico involves being poor. That said, we do see in Denmark, the Netherlands, Flanders, Sweden, etc. that it's actually quite possible for a country to become very much a part of the global economy while still retain a distinct language community.

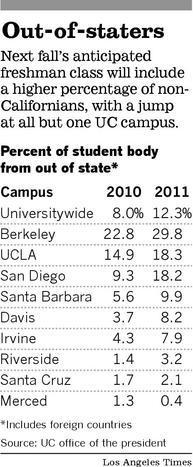

UC System Boosting Out Of State Enrollments

Matthew Kahn and Michael O'Hare both hail the trend toward more out of state enrollments in the University of California system. Kahn, the economist, makes the economist's case: "When you produce a high quality product, you can raise price without losing your market share [...] With the extra revenue, UCLA could subsidize tuition further for the needy."

O'Hare makes a broader argument about diversity, but in some ways I think Kahn's point is the more important one. And the question is what is the University of California in fact doing with the extra revenue. My fear is that what's happening is that the state is reducing its level of funding to the system, and the system is making up the gap by enrolling fewer Californians and more profit-making non-Californians. That is, for the UC system, a rational response. But it also reflects a trend toward privatization of the UC system and a declining level of public services for Californians. It's a trend that we should find troubling.

Now conversely, per Kahn you could imagine a more productive dynamic. The University of California does have a high-quality product. The high quality of the product could be used to offer quality college to more non-Californians and the extra revenue that brings in could be used to either lower the price for needy Californians or else (even better in my view) expand overall system capacity so that more Californians have the opportunity to go to college. There's nothing wrong, as such, with an institution having mixed public and private characteristics and at their most successful I think that's how both formally public and formally private colleges have operated in America. But a kind of stealthy move toward operating on a pure private motive isn't a good trend.

July 2, 2011

Competition Through The Courts

The mobile phone industry has been the scene of enormous competition and innovation. Mostly this has taken the form of software and hardware companies hiring engineers to try to build better mobile devices and sell them to consumers. Firms have risen and fallen, and nobody knows where it will end. But what we do know for sure is that all of us now have access to much better phones than were available five years ago. It's like a capitalist's dream. And then we have the bidding over the corpse of Nortel Networks:

Google is the youngest of these companies and has probably the smallest patent portfolio, most of which isn't mobile or telecom related. This puts Google and Android at a legal disadvantage and explains the 45 patent infringement suits that one analyst says Google in presently facing in the mobile area alone. Google would have preferred to win the auction, but with the consortium sitting on more than $100 billion in cash, the outcome came down to determination, not resources. Google stayed in it only long enough to make sure of the consortium's intentions and to make the purchase more painful for them, if that mattered. It certainly mattered to Google, because that $4.5 billion number will be at the heart of the inevitable anti-trust lawsuit Google will file almost immediately. Every good anti-trust lawyer in America just cancelled his or her July 4th holiday to prepare their pitch for Google, which will probably claim Restraint of Trade as well. Given that the courts will shortly be involved, Google can probably operate unfettered for another 2-3 years, during which they'll try to build their own mobile patent portfolio. Google may well be able to use the courts to slow the actual Nortel transaction, too, according to my lawyer friends.

This kind of competition in which huge sums of money are sent to lawyers and consultants has a very different dynamic. When Google and Apple compete with one another in terms of designing better products, they're both trying to enrich themselves. But their efforts spill over and enrich consumers at large. When Google and Apple compete with one another in terms of designing better lawsuits, they're both trying to enrich themselves. But in this case, their efforts spill over and enrich law firms.

How Much Testing Is Too Much?

Jon Chait notes that opponents of using standardized tests to measure teacher quality are often exaggerating the extent to which anyone is proposing to rely on such tests:

Different states have different ways of measuring teacher performance. But none of them use student test scores as more than 50% of the measure (PDF). Classroom evaluations and other methods account for half or more of the measures everywhere.

This is, obviously, an important aspect of a well-designed evaluation system. In part, that's because no test can capture everything that matters. In part, it's because adding alternate evaluation methods into the mix is an important check against "teaching to the test" in too direct a way. And last it's important because you need different evaluative methods in order to try to check and see if your methods make sense. If the results of your tests and the results of your classroom evaluations are constantly sending diametrically opposed messages, then you're probably doing something wrong. If you're interested in this sort of thing, Susan Headden recently published a detailed account of what specifically happens in DCPS's super-controversial new IMAPCT teacher evaluation system. If you've heard that it just consists of Michelle Rhee administering standardized tests and firing people at random, you're mistaken.

Are These Hostilities?

The clandestine American military campaign to combat Al Qaeda's franchise in Yemen is expanding to fight the Islamist militancy in Somalia, as new evidence indicates that insurgents in the two countries are forging closer ties and possibly plotting attacks against the United States, American officials say. An American military drone aircraft attacked several Somalis in the militant group the Shabab late last month, the officials said, killing at least one of its midlevel operatives and wounding others.

Legal issues aside, it's worth remembering the history in Somalia. When the Bush administration first started directly re-involving American military forces in Somalia, the evidence that the people we were fighting had any substantial links to transnational terrorism or desire to attack the USA was tenuous at best. But once we started fighting against them, it's the most natural thing in the world for them to start forging deeper links with US enemies elsewhere and thinking of ways to fight back. For four or five years now, we've spiraled deeper into this conflict. And at each step, yes, it appears that we're fighting legitimate bad guys. But where down the path has our involvement improved the situation?

Lack Of Demand

Jeremy Hobson interviews Larry Summers who, rightly, sees lack of demand rather than lack of consensus about the long-term budget situation as America's primary problem:

SUMMERS: I worry about a number of things with respect to growth. Most profoundly I worry about lack of demand in the United States. That means that factory capacity is unused, it means that buildings sit empty, it means that too many people are unemployed. And I look for measure that will serve to promote the level of demand in the United States. That's why using this moment to repair our infrastructure is so important. That's why I believe that the payroll tax cuts that put money in people's pockets and increased employers incentives to hire are so important. And that's why I believe that opening foreign markets and promoting U.S. exports which creates more demand is so important. And China is obviously an important part of that story.

Exactly so. The "normal" economic problem for a country to have is that nearly all its resources are being used, and yet people sill don't have as much stuff as they want. That's a tough problem to solve, and it's forgivable if at times policymakers struggle with it. But we have the problem of vast resources going unused. Factories that don't run all the time. Able-bodied men and women who aren't working. Construction equipment lying idle. Office and retail space vacant. It's a strange problem to have and it's stranger still to see a US Congress that's so uninterested in doing anything about it.

China's Stimulus

Word from Prime Minister Wen Jiabao :

The thrust of China's response to the crisis is to expand domestic demand and stimulate the real economy, strengthen the basis for long-term development and make growth domestically driven. We have implemented a two-year, Rmb4,000bn ($618bn) investment programme covering infrastructure development, economic structural adjustment, improving people's well-being and protection of the environment. As a result, 10,800 km of railways and about 300,000 km of roads have been built and 210m kW of installed capacity for power generation have been added. We have boosted support for science and technology including by encouraging companies to carry out technological upgrading and innovation. More than Rmb1,000bn have been spent in rebuilding after the Wenchuan earthquake. In the affected areas, quality infrastructure and public facilities were constructed, and 4.83m rural houses and 1.75m urban apartments were rebuilt or reinforced. The quake-hit areas have taken on a new look. We are working to improve the balance between domestic and external demand, with the share of trade surplus in GDP dropping from 7.5 per cent in 2007 to 3.1 in 2010. China's rapid growth and increase in imports are an engine driving the global recovery.

Now obviously what Wen doesn't add to that is "and a lot of this new construction is pretty wasteful." But the reality is that it is. People often say that China has a billion people. But it doesn't. It has over 1.3 billion people. China is about as close to having a billion residents as the United States is to having eleven residents. Consequently, when you try to implement a very large scale government stimulus package in such a large scale country, you end up with, yes, a lot of waste. Hence the stories of ghost suburbs and so forth that you see in the press. That said, the question of waste ought to be in part a question of what is it that's being wasted. Is China running out of concrete? Running out of steel? Running out of glass? No. It's a waste in the sense that, in theory, that manpower and material that went into building it could have been used to build something else.

Compare that to the United States where we've done much less in the way of expansionary policy. The result has been much less waste. Instead, we've had years of mass unemployment. But that, too, is a waste. It's millions of people sitting around feeling depressed and demoralized watching their job skills slowly but surely erode. It helps economize on concrete, but at the expense of wasting human potential. I don't think we came away with the better deal.

Forgot About [John] Jay

A bit late, but Will Wilkinson notes that rather than reaching implausibly for non-Founder John Quincy Adams, Michele Bachmann could have cited some :

The really odd thing about this is that she is not altogether wrong, but she can't seem to get the right part right. Plenty of founders did fight hard to end slavery, but Ms Bachmann doesn't seem to know who they were. Part of the problem may be that conservatives' favourite founders, Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, held large numbers of human beings as slaves and did less than a lot about it. The really good guys on the slavery issue—which is to say on the human freedom issue—were not the Virginia plantation masters but the less-venerated "big government" Yankee founders who sped the abolition of slavery in the north.

The American Spectator's Jeffrey Lord twists a bit to put Jefferson and Madison in a favourable light, and it's true that both wanted slavery to end eventually. Mr Lord gets warmer when he notes Alexander Hamilton's role in the New York Manumission Society. But it was John Jay who was the real mastermind behind this admirable enterprise, and he got essential help from other legit founders like Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and my favourite, Gouverneur Morris (pictured). So how about some love for John Jay, a slaveholder of whom I think one can truly say that he worked tirelessly to end slavery? And Jay did more than get the New York Manumission Society off the ground.

Jay not only founded the African Free School in New York City, as Governor of New York he signed the bill that ended slavery. Something people forget about the politics of slavery in the Founding era is that slavery existed at that time in the north, and was generally perceived as being on the wane in general. Some politicians, primarily in the northern states, took action and actually abolished slavery and that's why slavery went away in the north. Southern politicians who claimed to favor gradual emancipation could have, but didn't, pass actual legislation embodying this vision.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers