Rob Kitchin's Blog, page 185

February 28, 2013

February reads

This month of reading has been probably been the best since I started the blog. I hit a streak of very good books, all of which I'd recommend. It's difficult picking a book of the month with three five star reads in the mix (and thankfully I'm still a few pages from the end of White Dog by Peter Temple, otherwise I'd have more of a headache). I'm going to give it as a tie between Hard Bite and The Sea Detective. Beyond being excellent reads, they both also managed to be fresh and original.

This month of reading has been probably been the best since I started the blog. I hit a streak of very good books, all of which I'd recommend. It's difficult picking a book of the month with three five star reads in the mix (and thankfully I'm still a few pages from the end of White Dog by Peter Temple, otherwise I'd have more of a headache). I'm going to give it as a tie between Hard Bite and The Sea Detective. Beyond being excellent reads, they both also managed to be fresh and original. Six Bad Things by Charlie Huston ****

Too Big to Know by David Weinberger ***.5

In Search of Klingsor by Jorgi Volpi ****

Information: A Very Short Introduction by Luciano Floridi ****

The Sea Detective by Mark Douglas-Home *****

Piggyback by Tom Pitts ****.5

Ratlines by Stuart Neville *****

Hard Bite by Anonymous-9 *****

Bed of Nails by Antonin Varenne ****

Published on February 28, 2013 05:15

February 27, 2013

Review of Too Big to Know by David Weinberger (2011, Basic Books)

In Too Big to Know, David Weinberger (2011) develops a materialist argument with regards to the relationship between the medium and nature of communication, arguing: ‘[t]ransform the medium by which we develop, preserve, and communicate knowledge, and we transform knowledge.’ Such arguments have been made by others, such as Kittler in his book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, where he sets out how each of these technologies transformed knowledge production and changed how people relate to and interact with knowledge. Of course, it’s not just technologies that shape the creation of knowledge, but social and cultural milieu with, for example, the notion of authorship and readership shifting over time in response to political transformations such as the Renaissance and Enlightenment.

In Too Big to Know, David Weinberger (2011) develops a materialist argument with regards to the relationship between the medium and nature of communication, arguing: ‘[t]ransform the medium by which we develop, preserve, and communicate knowledge, and we transform knowledge.’ Such arguments have been made by others, such as Kittler in his book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, where he sets out how each of these technologies transformed knowledge production and changed how people relate to and interact with knowledge. Of course, it’s not just technologies that shape the creation of knowledge, but social and cultural milieu with, for example, the notion of authorship and readership shifting over time in response to political transformations such as the Renaissance and Enlightenment.Weinberger is no doubt right that the formulation, communication and nature of knowledge is presently being transformed by the internet through the radical ‘networking of knowledge’. Knowledge, he argues, ‘is now a property of the network’, altering its shape and nature, wherein ‘[t]he smartest person in the room is the room itself: the network that joins the people and ideas in the room, and connects to those outside of it.’ Knowledge is framed not as ‘a library but a playlist’. In an engaging narrative, he contends that the networking of knowledge leads inevitably to knowledge without a firm foundation (networks do not have bases); an elimination of gatekeeping and filtering; and an erosion of the value of tokens of credibility, authority and reputation; thus leading to a flattening and democratisation of knowledge production and sharing.

His arguments with regards to filtering forward and credibility, however, overstate the case that there is a flattening and democratisation of information. Yes, search engines do provide links to all relevant pages rather than filtering out, but in filtering forward they order and weight the material. That ordering pushes those searching towards certain kinds of sites; often ones owned by corporations and institutions. Indeed, the internet is inhabited by the bastions of traditional media, such as publishers, newspapers, radio and television, and they are still dominant sources of news and analysis which continue to work by filtering out. And whilst there is a move to open access, much valuable knowledge still exists behind pay walls - whether that is on the internet or in traditional media, such as the Weinberger’s book. Indeed, data and data analytics are massive, multi-billion dollar industries, and that is unlikely to change any time soon, even with the opening up of some data and information. The push towards open access has been accompanied by attempts to extend and tighten intellectual property regimes, and there is an on-going tussle between public good and private profit (though both are increasingly networked). Moreover, hierarchies of credibility, authority and reputation are re-established on the internet, not erased; most often on along the usual institutional lines. As a result without some form of credibility and authority, individuals can post material on their own pages, but readership will be much smaller than on institutional sites where it is penned by authors who have forms of cultural capital established through the usual institutional channels. Further, the means of sharing maybe more democratic (assuming you have the resources, literacy and time to be online and post material), but the distribution of attraction, influence and power have not been made even and equal. This suggests that far from the traditional pyramid of knowledge being reconfigured into a network, the situation is more complex.

This is not to say that the internet is not changing how knowledge is produced, shared and debated, it most certainly is. Rather, knowledge will continue to display a certain lumpiness rather than flattening. To a degree this is illustrated by the self-acknowledged irony and hypocrisy evident in the medium Weinberger uses to communicate his thesis - a traditionally published book that has closed, paid access, is protected by copyright as opposed to having a creative commons license (he strongly advocates open access and open licensing), is not interlinked beyond tradition references, and seeks to claim authority and credibility through the gatekeeping and investment of a publisher and his institutional affiliation at Harvard. We might be entering a new phase in the nature of knowledge, and Weinberger undoubtedly raises some important questions to ponder, but he undermines his own argument through the very choice of medium it is made through.

Nevertheless this is an interesting and thought-provoking book, written in an engaging and easy-to-follow style.

Published on February 27, 2013 04:55

February 25, 2013

Review of Six Bad Things by Charlie Huston (Ballantine Books, 2005)

After being in the wrong place at the wrong time and barely surviving murder and mayhem in New York, Hank Thompson has been hiding out in Mexico in a beach hut, keeping his head low and living a life that doesn’t suggest he has four and half million dollars buried in the sand. The Russian mafia though has long memories and tentacles and when a nosy backpacker turns up, Hank knows it’s time to move out. He also knows he needs to try and protect his parents who, now the mafia know he’s alive, have become a potential leverage point. Getting out of Mexico and into the US, however, is not straightforward when you’ve corrupt policemen on your trail and you’re on the ten most wanted fugitives list for crimes you mostly didn’t commit. After four years of relative calm, a vicious tornado has been released and its tracking Hank from Mexico to California to Las Vegas, attracting head cases and spitting out dead bodies. Hank is not about to roll over though and accept defeat, even if it just leads him further into trouble.

After being in the wrong place at the wrong time and barely surviving murder and mayhem in New York, Hank Thompson has been hiding out in Mexico in a beach hut, keeping his head low and living a life that doesn’t suggest he has four and half million dollars buried in the sand. The Russian mafia though has long memories and tentacles and when a nosy backpacker turns up, Hank knows it’s time to move out. He also knows he needs to try and protect his parents who, now the mafia know he’s alive, have become a potential leverage point. Getting out of Mexico and into the US, however, is not straightforward when you’ve corrupt policemen on your trail and you’re on the ten most wanted fugitives list for crimes you mostly didn’t commit. After four years of relative calm, a vicious tornado has been released and its tracking Hank from Mexico to California to Las Vegas, attracting head cases and spitting out dead bodies. Hank is not about to roll over though and accept defeat, even if it just leads him further into trouble. Six Bad Things is the second in the Hank Thompson trilogy, though it can be read as a standalone (though I’d recommend reading the excellent Caught Stealing first). It starts relatively sedately with a wonderful scene about how Hank has become addicted to cigarettes, gains a little pace and then opens out full throttle. Huston excels at writing fast paced action sequences and riffing dialogue (the conversations between Hank and Sally are exceptionally good), and he strings these together into an endless succession of scrapes, highs and lows, and twists and turns. Hank is an engaging lead character, teetering on an anti-hero tightrope between goody and baddy, and the other characters are well penned, providing interesting foils. Whilst the story is an enjoyable romp, it’s not quite as engaging as Caught Stealing, a couple of bits seemed a little over-contrived, and the end was a wee bit flat, working more to set up the third instalment rather than closing this one off. Nevertheless, it is superior stuff, and anyone who enjoys fast-action noir with wise-cracking dialogue, will gallop through it wearing a wry smile. Bring on A Dangerous Man, the final instalment in the series.

Published on February 25, 2013 23:53

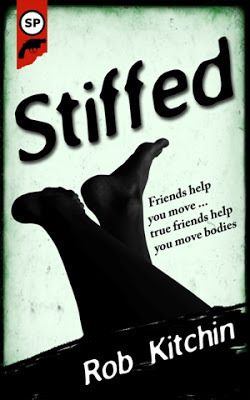

Stiffed cover

I've been working with the cover designer, Eric Beetner, on the cover for Stiffed. I had a few mocks, which I might post sometime, but we've gone for one that Eric concocted. Simple, bold and evocative. What do you think?

I've been working with the cover designer, Eric Beetner, on the cover for Stiffed. I had a few mocks, which I might post sometime, but we've gone for one that Eric concocted. Simple, bold and evocative. What do you think?Also check out Eric's own fiction. Here's my review of Dig Two Graves and I've The Devil Doesn't Want Me on my kindle.

I'm not sure of the release date for Stiffed, but once I know I'll pass it on.

Published on February 25, 2013 00:36

February 24, 2013

Lazy Sunday Service

Nearly all of the books I read are paperbacks. I do have a kindle, but I've tended to only use it when I'm travelling. I'm aware, however, that I have a few e-books building up (though nothing like the paper to-be-read pile). Here's what's waiting to be read. I hope to get to them over the next few months. The first one - The Polka Dot Girl - has an quirky angle: it's a noir in which every single character is female. It'll be interesting to see how successfully that works.

Nearly all of the books I read are paperbacks. I do have a kindle, but I've tended to only use it when I'm travelling. I'm aware, however, that I have a few e-books building up (though nothing like the paper to-be-read pile). Here's what's waiting to be read. I hope to get to them over the next few months. The first one - The Polka Dot Girl - has an quirky angle: it's a noir in which every single character is female. It'll be interesting to see how successfully that works. The Polka Dot Girl by Darragh McManus

Missing in Rangoon by Christopher G. Moore

Big Maria by Johnny Shaw

Karma Backlash by Chad Rohrbacher

The Devil Doesn't Want Me by Eric Beetner

A Healthy Fear of Man by Aaron Philip Clark

All the Lonely People by Martin Edwards

The Perfect Crime by Les Edgerton

The Barbershop Seven by Douglas Lindsay (books 1-7, Barney Thomson series)

My posts this week

Vacancy at individual property and town level

Review of In Search of Klingsor by Jorgi Volpi

Crime fiction from around the world

Review of Information: A Very Short Introduction by Luciano Floridi

Review of The Sea Detective by Mark Douglas-Home

Playing by the river

Published on February 24, 2013 06:53

February 23, 2013

Playing by the river

‘There. It’s a body.’

Kevin prodded the black plastic bag with a long stick and it bobbed between the reeds.

‘It’s not a body, it’s just some rubbish.’

‘I’m telling you, I saw fingers sticking out.’

‘You’ve been watching too much Lewis and Midsomer Murders. They always have nutters finding bodies in bags. It’s just some crap that a litterbug has dumped.’

He speared the bag, piercing the thin plastic and dragged it to the bank, the stick creating a tear, exposing an arm.

‘Shit,’ Kevin exclaimed, jumping back.

‘Told you!'

‘You think it’s real?’

‘I think we’re nutters.’

‘Cool.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words

Kevin prodded the black plastic bag with a long stick and it bobbed between the reeds.

‘It’s not a body, it’s just some rubbish.’

‘I’m telling you, I saw fingers sticking out.’

‘You’ve been watching too much Lewis and Midsomer Murders. They always have nutters finding bodies in bags. It’s just some crap that a litterbug has dumped.’

He speared the bag, piercing the thin plastic and dragged it to the bank, the stick creating a tear, exposing an arm.

‘Shit,’ Kevin exclaimed, jumping back.

‘Told you!'

‘You think it’s real?’

‘I think we’re nutters.’

‘Cool.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words

Published on February 23, 2013 02:45

February 22, 2013

Review of The Sea Detective by Mark Douglas-Home (2011, Sandstone Press)

Cal McGill is a part-time PhD oceanography student charting how the currents move free-floating objects, supplementing his studies by running Flotsam and Jetsam Investigations, which seeks to track and source particular items such as nets and oil spills for a variety of agencies. He has a particular interest in charting the movement of bodies, seeking the location where his grandfather may have been washed ashore on the Norwegian coast in the Second World War. He’s also a part-time eco-warrior, highlighting the issue of climate change by planting a particular, symbolic plant in the gardens of senior Scottish government figures. Only on his latest escapade he’s been caught on camera. DI David Ryan, a misogynist and careerist cop, would like to throw the book at Cal, but nobody else wants to press charges, least of all the politicians, wary of how it will play out in the media. Nonetheless Cal and photographs of his work and his grandfather appear in several newspapers. The story is seen by an Indian girl on the run from her pimps, who recognises a photo of her friend who’d disappeared three years earlier pinned to his map, and also prompts Cal’s ex-wife to make contact to tell him she’s making a documentary about the remote island where his grandfather used to inhabit and that she’s met an old woman who’d like to talk to him. The first sees him drawn into the dark world of sex trafficking, the latter prompts him to confront his grandfather’s past and the rumours surrounding his death. Meanwhile, Ryan and his put-upon, overweight colleague, Helen Jamieson, has been assigned to investigate the appearance of three feet that have been washed up onto different beaches. Ryan sees it as a path to promotion, but refuses to use Cal’s expertise and wants Jamieson to do all the work whilst he builds his media profile. Jamieson is fed-up of being bullied by her obnoxious boss and wants to claim the credit of solving the case, and has no issues with using Cal on the quiet. Drawn into these various strands, the sea detective will either drown or steer a path through stormy currents.

Cal McGill is a part-time PhD oceanography student charting how the currents move free-floating objects, supplementing his studies by running Flotsam and Jetsam Investigations, which seeks to track and source particular items such as nets and oil spills for a variety of agencies. He has a particular interest in charting the movement of bodies, seeking the location where his grandfather may have been washed ashore on the Norwegian coast in the Second World War. He’s also a part-time eco-warrior, highlighting the issue of climate change by planting a particular, symbolic plant in the gardens of senior Scottish government figures. Only on his latest escapade he’s been caught on camera. DI David Ryan, a misogynist and careerist cop, would like to throw the book at Cal, but nobody else wants to press charges, least of all the politicians, wary of how it will play out in the media. Nonetheless Cal and photographs of his work and his grandfather appear in several newspapers. The story is seen by an Indian girl on the run from her pimps, who recognises a photo of her friend who’d disappeared three years earlier pinned to his map, and also prompts Cal’s ex-wife to make contact to tell him she’s making a documentary about the remote island where his grandfather used to inhabit and that she’s met an old woman who’d like to talk to him. The first sees him drawn into the dark world of sex trafficking, the latter prompts him to confront his grandfather’s past and the rumours surrounding his death. Meanwhile, Ryan and his put-upon, overweight colleague, Helen Jamieson, has been assigned to investigate the appearance of three feet that have been washed up onto different beaches. Ryan sees it as a path to promotion, but refuses to use Cal’s expertise and wants Jamieson to do all the work whilst he builds his media profile. Jamieson is fed-up of being bullied by her obnoxious boss and wants to claim the credit of solving the case, and has no issues with using Cal on the quiet. Drawn into these various strands, the sea detective will either drown or steer a path through stormy currents. The Sea Detective is a hugely enjoyable read, told in an engaging and compelling voice. An awful lot happens in its 280 pages, with its three main intersecting plot lines, but at no point does the story feel overcomplicated or underdeveloped or overly contrived. Packing so much in, in terms of historical, social and scientific contextualisation and the back stories of the various characters, whilst keep the story front and centre without the text becoming bloated or preachy is a remarkable feat. The characterisation is excellent, especially the lead characters of Cal McGill, DC Helen Jamieson, Basanti, and DI Ryan, who all are complex and three-dimensional (I especially liked Jamieson as the intelligent but overweight cop who craves recognition and acceptance, but is misjudged and mocked by her colleagues). Douglas-Home is particularly good at framing and playing out a scene and the interactions between characters. There is a strong sense of place throughout, especially with respect to rural, coastal Scotland. The plotting is, in my view is exceptional, creating a story that hooks the story in and incessantly tugs them along on a gripping, emotional journey. Overall, an excellent first novel that I’d thoroughly recommend. I’ll definitely be reading the next in the series.

Published on February 22, 2013 02:30

February 20, 2013

Review of Information: A Very Short Introduction by Luciano Floridi (2010, Oxford University Press)

A short review of a short book. Writing a concise, but quite thorough and balanced overview of a concept is no easy task. Floridi largely succeeds. To do so he is necessarily selective in his approach, focusing on information from a largely information theory perspective, whilst framing that within wider understandings, the development of the information society, and the era of big data. The narrative is clear and straightforward to follow, with plenty of examples, and lots of signposting. Chapters cover mathematical, semantic, physical, biological and economic information, as well as a brief discussion of some ethical issues. A handy, introductory guide to one of the defining concepts of our age.

A short review of a short book. Writing a concise, but quite thorough and balanced overview of a concept is no easy task. Floridi largely succeeds. To do so he is necessarily selective in his approach, focusing on information from a largely information theory perspective, whilst framing that within wider understandings, the development of the information society, and the era of big data. The narrative is clear and straightforward to follow, with plenty of examples, and lots of signposting. Chapters cover mathematical, semantic, physical, biological and economic information, as well as a brief discussion of some ethical issues. A handy, introductory guide to one of the defining concepts of our age.

Published on February 20, 2013 02:01

February 19, 2013

Finding crime fiction from around the world

I do a fair bit of travelling and I always try to read fiction set wherever I'm visiting. As a result, I'm often looking for recommendations for suitable books. I've been pointed in the direction of a useful resource - the Stop You’re Killing Me database. It allows you to browse its database of crime fiction from around the world, listing authors and series for each locale. I'll no doubt make use of it, but whilst it is a useful resource, I'll probably still put up posts asking for suggestions as I find personal recommendations about particular authors and series valuable in choosing a particular title (and also the database is less extensive outside of the US).

I do a fair bit of travelling and I always try to read fiction set wherever I'm visiting. As a result, I'm often looking for recommendations for suitable books. I've been pointed in the direction of a useful resource - the Stop You’re Killing Me database. It allows you to browse its database of crime fiction from around the world, listing authors and series for each locale. I'll no doubt make use of it, but whilst it is a useful resource, I'll probably still put up posts asking for suggestions as I find personal recommendations about particular authors and series valuable in choosing a particular title (and also the database is less extensive outside of the US).

Published on February 19, 2013 02:03

February 18, 2013

Review of In Search of Klingsor by Jorgi Volpi (1999 Spanish, 2004 Fourth Estate)

Francis X Bacon is a promising physicist in pre-war America. After a stellar undergraduate degree he’s taken on at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, working alongside such greats as Einstein and von Neumann. After a couple of indiscretions it’s suggested that he transfer to the US Army to work on science-related research. The war is now well underway and Bacon’s job is to help compile dossiers on Germany’s leading scientists. After the D-Day landings in Normandy he is shipped to the continent, working in a team hunting down physicists working on the German atomic programme. In the immediate post-war period he’s given the task of identifying ‘Klingsor’, the codename for supposedly the most senior scientist in the Nazi regime, responsible for allocating funds and resources to different programmes. To aid him in his task he recruits Professor Gustav Links, a mathematician and conspirator in the attempt on Hitler’s life in July 1944. Through a twist of fate, Links had survived the purges that followed. Together, Bacon and Links try to uncover the identity of Klingsor travelling to interview such luminaries as Planck, Heisenberg, Bohr and Schrodinger, but each time they seem to draw close they are cast into smoke and mirrors.

Francis X Bacon is a promising physicist in pre-war America. After a stellar undergraduate degree he’s taken on at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, working alongside such greats as Einstein and von Neumann. After a couple of indiscretions it’s suggested that he transfer to the US Army to work on science-related research. The war is now well underway and Bacon’s job is to help compile dossiers on Germany’s leading scientists. After the D-Day landings in Normandy he is shipped to the continent, working in a team hunting down physicists working on the German atomic programme. In the immediate post-war period he’s given the task of identifying ‘Klingsor’, the codename for supposedly the most senior scientist in the Nazi regime, responsible for allocating funds and resources to different programmes. To aid him in his task he recruits Professor Gustav Links, a mathematician and conspirator in the attempt on Hitler’s life in July 1944. Through a twist of fate, Links had survived the purges that followed. Together, Bacon and Links try to uncover the identity of Klingsor travelling to interview such luminaries as Planck, Heisenberg, Bohr and Schrodinger, but each time they seem to draw close they are cast into smoke and mirrors.In Search of Klingsor is, in many ways, a remarkable book. It is full of science, philosophy, metaphysics and the great personalities of early twentieth century physics. It not only binds together the story arc with historical episodes and explanations of atomic science and game theory, it uses the principles of the latter as narrative devices. For example, the entire tale is an illustration of game theory and uncertainty. The telling of Bacon’s life story and his encounters with the various scientists is well executed, with the personalities and histories of the latter vividly bought to life. Indeed, the story is rich in detail and for the most part cleverly and engagingly constructed, and the book is clearly based on extensive research. There is, however, a weakness in the structure. The telling is divided into three parts. If Volpi had found a way to conclude the story after the second part I have little doubt this would be one of my reads of the year. It really was a masterpiece up until this point. The third part, however, shifted focus to concentrate on Gustav Links, with the style and pace altering, and more problematically, it little advanced the story with regards to the search for Klingsor. It worked to take the wind out of the sails of what had been a thoroughly compelling yarn and also led to some loose ends, not least with respect to Bacon, creating somewhat of a weak conclusion. Nonetheless, the first 300 pages of this book were excellent; it was just a shame that the final 100 pages didn’t quite match them. Overall, if you’re interested in twentieth century physics and the German atomic programme, this is a fascinating and entertaining read.

Published on February 18, 2013 01:04