Alan Paul's Blog, page 6

March 19, 2019

Eric Clapton with the Allman Brothers 3/19/09

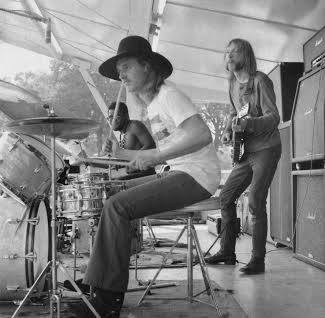

3-19-09 Photo – Kirk West

It’s March 19. On this day in 2009, Eric Clapton played the first of two nights with the Allman Brothers Band, the emotional and musical climax of an incredible 40th anniversary Beacon run.

I was in the house for night one, one of the handful of most exciting concerts of my life. I have often been skeptical of Eric Clapton and have found myself pretty dang bored at his shows a few times, but every time I’ve seen him with someone on stage who pushed him, he’s been damned good: Steve Winwood, Jimmie Vaughan, B.B. King, Stevie Ray Vaughan – and Derek Trucks. So my hopes were very high for this, and I knew exactly how much it meant to everyone in the Allman Brothers, especially Warren, a died-in-the-wool EC fanatic in his younger days.

The excitement around this show was contagious and the joint was buzzing and hopping long before Clapton took the stage. The first set was a superb, no-guests affair: Little Martha, Statesboro Blues, Done Somebody Wrong, Revival, Woman Across the River, Don’t Keep me Wondering and Whipping Post – a first set ender that signaled serious business.

At the break, a grand piano was rolled out and Gregg opened the second set with a solo “Oncoming Traffic” that was just gorgeous. The tension and the energy just kept building and after a few more songs, Clapton strolled out. The complete video of the performance is below – thank you Butch Trucks and Moogis! – and there’s so much to love in this performance. I give Clapton made props for learning the ABB songs and embracing the role, instead of just playing Stormy Monday and Key to the Highway, which still would have been cool. Most Beacon guests did not take their gig so seriously.

Watch the end of “Why Does Love Got to be So Sad” and the beautiful, aching interplay between Warren, Derek and Eric. As it ends, Clapton smiles with such contentment and when the final flourish hits, Butch thrusts his arms in the air in triumph. They all knew what they had just done… and then they go right into “Little Wing.” Please enjoy the One Way Out section about how this all came about:

GREGG ALLMAN: The one guy who of course my brother had a real thing with and had never played with the Brothers was Clapton and it was just real good to have him there. That was a long time coming and really fun and meaningful.

Derek Trucks, who spent a year touring the world with Clapton in 2006-07, facilitated the British guitarist’s appearance.

DEREK TRUCKS: I had mentioned it to him a few times, but the band wrote a letter – it was really important that it come from them – and I just made sure it got delivered. It was a group effort that basically said, “This is the Allman Brothers Band and we are paying tribute to Duane to celebrate our 40th anniversary. Please join us.”

BUTCH TRUCKS: We’ve been trying to jam with Eric for years but have never been in the same place at the same time. Eric is a big fan of the Allman Brothers, and when Duane died, probably his three best friends outside of our band were Eric Clapton, John Hammond and Delaney Bramlett. Eric and John were at the Beacon and Delaney had sadly died a few months earlier. That’s why it was so important to us to have Eric there.

WARREN HAYNES: It was a really big deal to the Allman Brothers Band because that had never happened, which is pretty incredible given the history between Duane and Eric. We were so honored to have him there and the fact it turned into seven or eight songs, going well beyond what we originally agreed upon, was icing on the cake. He was great to work with, he played great and everyone was on his best behavior because we all knew what a special moment it was.

We were all very impressed with Eric’s desire to learn Allman Brothers songs rather than just get up and jam and not just choose ones that would make it easy on everybody. We were hoping for the opportunity to play some of the centerpieces, like “Dreams” and “Liz Reed” and Eric was more than game. “Little Wing” was an afterthought and the coolest part of the rehearsal. Everything went very smoothly and when we had basically played through all the songs we agreed upon, Eric looked around and said, “Is there anything else we should think about? What about ‘Little Wing’?” Our group reaction was, “Well, we’ve never played it, but sure.” We started working it up from scratch and I thought it was one of the highlights.

Clapton’s “Little Wing” suggestion was particularly profound since it was Duane Allman’s idea to record it on Layla. Clapton and Haynes sang harmony vocals on the song. On Thursday, March 19, 2009, Clapton joined the band for six songs: “Key To The Highway,” trading vocal verses with Gregg, “Dreams,” “Little Wing” and Derek and the Dominos’ “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?”, “Anyday” and “Layla.” The next night, he also played “Stormy Monday” and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

ALLMAN: He took a private jet in from New Zealand or some place to be with us and then took it back to resume his tour. When he was here with us, he just gave it all. That was special, man.

DEREK TRUCKS: I knew he would come prepared but I was still a little taken back by how much energy he had put into it. He had only hung with Gregg once or twice and obviously Duane was very important to him. He told me that the time he went and saw the Allman Brothers in Miami he was blown away by them – what they looked like, how they sounded. It was a part of his life that he had never put away and he came loaded for bear.

HAYNES: Eric Clapton was my first guitar influence, along with Johnny Winter and Jimi Hendrix, so it was a very big personal moment for me as well. I sometimes forget how much I learned so much from him in my formative years, but it certainly came back those nights! And on top of that I sang a duet with him on “Little Wing,” I was just emotionally ecstatic.

DEREK TRUCKS: Afterwards, when we were hugging, Eric whispered in my ear, saying something like, “I haven’t played like that since 1969.”

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

Here’s the whole sit-in, from the first night, the night I was there, 3-19-09:

March 13, 2019

A Brief History of the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East

In honor of the 48th anniversary of the final night of the magical Fillmore East turn that produced the epic album. I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is a partial, very abridged version of Chapter 8. To read the full story of the making of At Fillmore East, pick up a copy of One Way Out.

Chapter 8.

LIVE ALIVE

Though their first two releases had caused barely a ripple in the marketplace, the band was drawing raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with superior musical precision and a deep grounding in the blues. A live album was the obvious solution. To cut the record, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights — March 11, 12 and 13, 1971. They were paid $1250 per show.

The Allman Brothers Band had made their Fillmore East debut December 26-28, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat and Tears for three night. Promoter Bill Graham loved the band and promised them that he would have them back soon and often, paired with more appropriate acts, and he lived up to this vow.

On January 15-18, 1970, the ABB opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. They were back in New York on February 11 for three nights with the Grateful Dead. These shows were crucial in establishing the band and exposing them to a wider, sympathetic audience on both coasts.

TRUCKS: You can’t put in words what those early Fillmore shows meant to us. The Fillmore West helped us get established in San Fran and it was cool – especially those shows with B.B. and Buddy – but the Fillmore East was it for us; the launching pad for everything that happened.

ALLMAN: We realized that we got a better sound live and that we were a live band. We were not intentionally trying to buck the system, but keeping each song down to 3:14 just didn’t work for us. We were going to do what the hell we were going to do and that was to experiment on and offstage. And we realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off; we need to make a live album.

BETTS: There was no question about where to record a concert. New York crowds have always been great, but what made the Fillmore a special place was Bill Graham. He was the best promoter rock has ever had and you could feel his influence in every single little thing at the Fillmore. It was just special. The bands felt it and the crowd felt it and it lit all of us up. The Fillmore was the high-octane gig to play in New York — or anywhere, really.

Bill Graham introducing the ABB. Photo by Sidney Smith. All rights reserved.

ALLMAN: That was the place to record and we knew it. It was a great sounding room with a great crowd, but what really made it special was the guy who ran it. Bill Graham called a spade a spade and not necessarily in a loving way. Mr. Graham was a stern man, the most tell-it-like-it-is person I have ever met and at first it was off-putting. But he was the fairest person, too, and after knowing him for while, you realized that this guy, unlike most of the other fuckers out there, was on the straight and narrow.

PERKINS: The Fillmores were so professionally run, compared to anything else at the time. And he would gamble on acts, bringing in jazz and blues and the Trinidad/Tripoli String Band – and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered.

DOWD: I got off a plane from Africa, where I had been working on the Soul To Soul movie [capturing a huge r&b, jazz and rock concert held in Ghana], and called Atlantic to let them know I was back and Jerry Wexler said, “Thank God; we’re recording the Allman Brothers live and the truck is already booked,” so I stayed up in New York for a few days longer than I had planned.

It was a good truck, with a 16-track machine and a great, tough-as-nails staff who took care of business. They were all set to go. When I got there, I gave them a couple of suggestions and clued them in as to what expect and how to employ the 16 tracks, because we had two drummers and two lead guitar players, which was unusual, and it took some foresight to properly capture the dynamics.

Dowd was thrilled with what he was hearing until the band unexpectedly brought out sax player Rudolph “Juicy” Carter and another horn player, as well as harmonica player Thom Doucette, a frequent guest who had played on Idlewild South.

DOWD: We were going along beautifully until the fourth or fifth number when one chap looked up and asked, “What do we do with the horns?” I laughed and said, “Don’t be a smart ass,” thinking he was joking, but three horn players had walked on stage. I was just hoping we could isolate them, so we could wipe them and use the songs, but they started playing and the horns were leaking all over everything, rendering the songs unusable.

JAIMOE: Dowd started flipping out when he heard the horns, but that’s something that could have worked. There’s no way that it would have ruined anything that was going on. It wasn’t distracting anyone, and it was so powerful.

Photo by Sidney Smith – Tulane U. homecoming, 1970. All rights reserved.

BETTS: Dowd was going nuts, but we were just having fun and everyone was enjoying it. We didn’t change our approach because we were recording. We never hired any of those guys. They’d just show up and sit in, and we all dug it.

PERKINS: The horn players would pop up and just sit in for a few songs. Those guys were friends of Jaimoe’s – we just knew them as Tic and Juicy and everyone liked their playing. Nothing was rehearsed with them. They’d just get up and play. Them showing up at those Fillmore gigs was a surprise to me and I didn’t think it was a good idea.

JAIMOE: Tic was a tenor player, Juicy played baritone and soprano – sometimes together, at the same time – and there was an alto player we called Fats, who was not at the Fillmore and didn’t come around as much. We had played together in Percy Sledge’s band and I knew them from Charlotte, NC. Good guys and good musicians.

PERKINS: They often had some heroin with them and were welcomed for that as well.

JAIMOE: I don’t know about that; if they showed up with a little something, it was probably because Duane or someone asked them to do so.

DOUCETTE: The plan was to bring on the horns full time. Duane would have liked to have 16 pieces. Duane had six different projects that he wanted to do and he just thought he could do it all at once on the same bandstand.

DOWD: I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, “The horns have to go!” and he went, “But they’re right on, man.” And I said, “Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.” He asked if the harp could stick around and I said, “Sure,” because I knew it could be contained and wiped out if necessary.

PERKINS: Doucette had played with the band a lot so he was a lot more cohesive with what they were doing. Duane loved those guys, but he would also listen to reason and I don’t think he put up any fight with Dowd.

DOWD: Every night after the show we would just grab some beers and sandwiches and head up to the Atlantic studios to go through the show. That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again. They would craft the setlist based on what we still needed to capture.

BETTS: You have to listen to it being played back to get a sense of whether or not it came together and we loved having that opportunity. We just thought, “Hey this is cool… I didn’t know I did that… That sounds pretty neat.” We were just enjoying ourselves and the opportunity to listen to our performances. We didn’t do a lot of that board tape stuff and we weren’t real hung up on the recording industry anyhow. We just played and if they wanted to record it they could. We were young and headstrong: “We’re gonna play. You do what you want.”

We just felt like we could play all night and sometimes we did. We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on there. All we did was edit some of the harmonica out, where there was a solo that maybe didn’t fit. It wasn’t doctored up, with guitar solos and singing redone in the studio, as on so many live albums. Everything you hear there is how we played it. We weren’t puzzled about what we were playing. We were a rock band that loved jazz and blues. We really loved the Dead, Santana, the Airplane, Mike Finnigan, and all the blues and jazz greats.

TRUCKS: We were listening to people like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and emulating them and trying to add that level of sophistication to our music – to add jazz and improvisation to blues, rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

DOWD: The Fillmore album captured the band in all their glory. The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove. Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East. Here was a rock ’n’ roll band playing blues in the jazz vernacular. And they tore the place up.

BETTS: There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album: that was a hell of a band and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like. I think it’s one of the greatest musical projects that’s ever been done in any genre. It’s an absolutely honest representation of our band and of the times.

JAIMOE: Fillmore was both a particularly great performance and a typical night. That’s what we did!

ALLMAN: You want to come out and get the audience in the palm of your hand right away: “1-2-3-4, bang! I gotcha!” That’s what you gotta do. You can’t be namby-pamby; you can’t be milquetoast with the audience.

WALDEN: Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album. Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing was what they were all about, not recording, that a phonograph record was confining to a group like this.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

February 12, 2019

Celebrating Eat A Peach on its anniversary

In honor of the 47th anniversary of the release of Eat A Peach – it came out February 12, 1972 – I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is a very partial, very abridged version of the story, with materials from Chapters 11 – 13. To read the full story of the making of Eat A Peach, pick up a copy of One Way Out.

*

In October, 1971, Allman Brothers Band completed three songs for their third studio album working with Tom Dowd at Miami’s Criteria Studios: Dickey Betts’ sweet, lilting “Blue Sky,” Gregg’s “Stand Back,” the only song in the band’s catalog to feature Jaimoe alone on drums, and “Little Martha,” a lovely duet with Betts and Duane – and the only song which Duane was ever credited with writing.

In October, 1971, Allman Brothers Band completed three songs for their third studio album working with Tom Dowd at Miami’s Criteria Studios: Dickey Betts’ sweet, lilting “Blue Sky,” Gregg’s “Stand Back,” the only song in the band’s catalog to feature Jaimoe alone on drums, and “Little Martha,” a lovely duet with Betts and Duane – and the only song which Duane was ever credited with writing.

The band took a break and returned to the road for a short run of shows, ending on October 17 at the Painter’s Mill Music Fair in Owings Mill, Maryland. They sold 2219 out of 2500 available tickets and made $12,647.

With almost everyone in the band and crew struggling with heroin addictions, four of them flew to Buffalo and checked into the Linwood-Bryant Hospital for a week of rehab: Duane, Oakley, Payne and Red Dog. A receipt shows the band’s general bank account purchased five roundtrip tickets on Eastern Airlines from Macon to Buffalo for $369. Gregg was supposed to go as well and a receipt from the hospital shows that he was one of the people for whom a deposit was paid. He apparently changed his mind at the last minute.

Leaving Buffalo, Duane spent one day in New York, then joined the rest of the band in Macon, returning the evening of October 28. The next day was the birthday of Linda Oakley, Berry’s wife, and a party was planned at the Big House. Duane visited for a while, then got on his Harley Davidson Sportster, which had been modified with extended forks that made it harder to handle. He had also cut the helmet strap so the protective headgear could not be secured. Dixie Meadows and Candace Oakley trailed him in a car.

Coming up over a hill and dropping down, Allman saw a flatbed lumber truck blocking his way. Duane pushed his bike to the left to swerve around the truck, but realized he was not going to make it and dropped his bike to avoid a collision. He hit the ground hard, the bike landing atop him. Duane was alive and initially seemed okay, but he fell unconscious in the ambulance and had catastrophic head and chest injuries. He died in surgery three hours after the accident. The cause of death was listed as “severe injury of abdomen and head.” He was 24 and had been playing slide guitar for less than four years.

Stunned and grieving, the band took a short hiatus before regrouping, gravitating back towards each other and immersion in their work. They committed to fulfilling previously scheduled dates in New York. Their first appearance without their leader was at CW Post College in Long Island on November 22, 1971; it was exactly three weeks after Duane’s funeral

BUTCH TRUCKS: We thought about quitting because how could we go on without Duane? But then we realized: how could we stop? We all had this thing in us and Duane put it there. He was the teacher and he gave something to us — his disciples — that we had to play out. We talked about taking six months off but we had to get back together after a few weeks because it was too lonely and depressing. We were all just devastated and the only way to deal with it was to lay.

WILLIE PERKINS: There were intensely mixed feelings at these shows. It was so painfully obvious that Duane wasn’t there, which created such an empty feeling. You missed him so damn bad, but you also really wanted to prove that it was going to be okay, that there was still a reason to be out there, that the band could do it. There was a tremendous sense of pulling together.

BUNKY ODOM: I can’t imagine what Dickey went through. Here you’ve got Duane in Dickey’s ear all night long and all of a sudden it’s not there any more. How do you fill those shoes? It was just horrible.

JAIMOE: I really can’t remember anything about any of these shows. We just had to play and everyone played and you really didn’t know what you missed more about Duane – being on stage with him or just life in general.

RED DOG: The day after we’d come back from being on tour, living on top of each other for weeks on end, we’d be home and I’d miss Duane and be banging on his door to say hello. Realizing I couldn’t bang on that door hurt, man. It was stunning.

Returning to Miami, the band recorded four more outstanding tracks with Dowd, including “Melissa,” Betts’ instrumental “Les Brers In A Minor” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” Gregg’s defiant response to his brother’s passing.

Friends of the Brothers: Paul, Levin, Aledort, Mack, Williams and more. Brooklyn Bowl tickets: https://ticketf.ly/2Auidia

GREGG ALLMAN: I wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” for my brother right away. It was the only thing I knew how to do right then.

TRUCKS: Of course, the music we recorded was all about Duane. Gregg wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and that was obviously about how to deal with this tragedy, but I think “Les Brers in A Minor” is about Duane just as much. We did everything we could to try and fill the gap and “Les Brers” was Dickey’s response — starting with the title, which is bad French for “less brothers.”

DICKEY BETTS: When I wrote “Les Brers” everyone kept saying they had heard it before, but no one could figure out where, including me. But it’s in my solo on “Whipping Post” from one night. It was just a lick I was playing in there, and years later it showed up in a bootleg, which was kind of amazing. I mean, none of us knew where it came from until that tape surfaced years later. It just sounded familiar.

TRUCKS: We were all putting more into it, trying so hard to make it as good as it would have been with Duane. We knew our driving force, our soul, the guy that set us all on fire, wasn’t there and we had to do something for him. That really gave everybody a lot of motivation. It was incredibly emotional.

BETTS: It was difficult to suddenly have to play slide and I put in some time to get my part down for “Ain’t Wasting Time No More.” I’ve always enjoyed playing acoustic slide and would even often play it with Duane; when the two of us played acoustic blues I was often the one with the slide, but I never cared as much for playing electric slide.

The band also recorded “Melissa,” a song Gregg had written in 1967 — he says it is his first tune he ever considered a keeper after several hundred — but had never recorded.

ALLMAN: When we were finishing Eat a Peach, we needed some more songs and I knew my brother loved “Melissa.” I had never really shown it to the band. I thought it was too soft for the Allman Brothers and was sort of saving it for a solo record I figured I’d eventually do.

The double album Eat A Peach was completed with three live songs: “One Way Out” from the June 27, 1971 final concert at the Fillmore East, and two songs recording during the March At Fillmore East performances: “Trouble No More” – the Muddy Waters track that had been the first song Gregg sang with the band – and the epic, 33-minute “Mountain Jam.” The latter, which took up both sides of a vinyl album, had been an evolving staple of their performances almost since the beginning.

TOM DOWD: When we recorded At Fillmore East, we ended up with almost a whole other album worth of good material, and we used [two] tracks on Eat A Peach. Again, there was no overdubbing.

ALLMAN: We always planned on having “Mountain Jam” on this album. That’s why you hear the first notes of the song as “Whipping Post” ends on At Fillmore East.

TRUCKS: That “Mountain Jam” is only on there because it’s the only version we had on multi-track tape and it was such a signature song of the band with Duane that we simply had to have it on a record. We played it many times so much better, but better a relatively mediocre version than nothing at all.

BETTS: That was probably the worst version of “Mountain Jam” we ever played. When we were recording live, we really were still focused on the crowd rather than the recording.

With recording done, the album had to be mixed. Dowd started the process, but the album had run over and he had other commitments, so Sandlin was called to Miami.

JOHNNY SANDLIN: I think Tom had to work with Crosby Still and Nash. I went down to Miami the last day Tom was still working on it, and sat with him, and he showed me what he was doing and discussed some aspects of recording. As I mixed songs like “Blue Sky,” I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there’s not going to be any more from him.

I was very proud of my work on Eat A Peach but really pissed because I did not receive credit, only a “special thanks.” It was the first platinum record I’d ever worked on and it meant a lot to me, so that felt like a slap.

TRUCKS: After we were all done and the album was being finalized, I walked into Phil’s office and they showed me the beautiful artwork, with this title on it: The Kind We Grow in Dixie. I said, “The artwork is incredible, but that title sucks!”

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

Then I hand-lettered the Allman Brothers name and photographed it with a little Kodak camera and had it developed at the drugstore, then cut the letters out and pasted them on the side of the truck, under the peach. Duane was still alive and the album had not been titled. We figured we’d go back and add that.

TRUCKS: Duane didn’t like to give simple answers so when someone asked him about the revolution, he said, “There ain’t no revolution. It’s all evolution.” Then he paused and said, “Every time I go South, I eat a peach for peace.” That stuck out to me, so I told Phil, “Call this thing Eat a Peach for Peace,” which they shortened to Eat A Peach.

It didn’t occur to me until decades later that Duane’s comment was a reference to T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” though I knew Duane was a big fan. I was reading Prufrock and came across the reference to eating a peach and was blown away. The symbolism is obvious. Prufrock was totally anal and didn’t want to do anything that would get messy and there’s nothing messier than eating a peach. Duane would have loved that metaphor.

POWELL: The cover was kind of a new approach, a soft sell, because it did not say the name of the album – and the name of the band was just in tiny letters. We left that to a sticker on the shrink-wrap. When we showed it to someone at the label, he said, “They are so hot right now, they could sell it in a brown paper bag.”

The double album opened up as a gatefold filled with another Wonder Graphics piece of art; an entire universe that seemed to promise some kind of psychedelic paradise. It told a story of happy, mystical brotherhood that was receding ever further into fantasy as the band grappled with the tragedy of Duane’s death.

POWELL: That was really a cooperative venture between Jim and I, completed with almost no planning or discussion. We were working on a large piece of illustration board, on a one-to-one scale – it was the size of the actual spread – and we just started drawing, with Jim’s work primarily on the left and mine on the right. This work was profoundly influenced by [Hieronymous] Bosch.

The whole thing was done over the course of one day while we were in Vero Beach, Florida. While one of us was drawing or painting, the other was out swimming in the ocean. We swapped off this way with virtually no conversation about the drawing, just fluid tradeoffs.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

January 24, 2019

Butch Trucks gone two years today

Wow. It’s been two years since we lost Butch Trucks.

Below is a verbatim repost of what I wrote the next day in a haze of sadness, confusion, anger and exhaustion. There are some edits I would normally make, but I think it best to let the rawness stand. I was operating on no sleep because I had gotten a call confirming the awful news at midnight and spent all night staring at the ceiling in disbelief, tossing and turning in anguish, anger and self recrimination.

It was a shocking day and it remains shocking now if I pause to give it any depth of thought. I think of Butch sometimes in the middle of driving or walking and gasp at the realization of what happened. I still can’t fully accept it and I don’t think I ever will.

As with all suicides of someone you knew and cared about, Butch’s death left me questioning my own actions or lack thereof. Could I have done anything? Should I have been aware of the depth of his sadness? Would any of it have mattered? I do feel certain that Butch had no idea about the breadth and depth of love and caring for him, a heartbreaking realization every time it enters my mind.

A month later, I organized a grand tribute to Butch at the since-closed American Beauty with help from my friends at Live for Live Music. Here’s my report on that event, which led directly tot he formation of Friends of the Brothers. Each and every show we play is in part a tribute to Butch.

Rest in Peace Butchy. You are missed more deeply by more people than you ever could have known.

Butch had the fire until the end.

Claude Hudson “Butch” Trucks (b. May 11, 1947, d. January 24, 2017)

It’s with a very heavy heart that I report the death of Butch Trucks, drummer, founding member and bedrock of the Allman Brothers Band. I am stunned to be writing these words, having communicated with Butch several times in just the past few days. My fingers are frozen just looking at the top of this page and seeing the words pouring onto my screen

Butch was devastated and angry about Trump’s election and had vowed to live at his house in the South of France throughout the new president’s term, but I doubted his resolve because he loved his grandchildren too much; I watched him light up with joy holding his new grandson at last summer’s Peach Festival. He was also very excited about playing with two bands: his Freight Train Band and The Brothers, recently renamed from Les Brers, featuring his Allman Brothers backline mates Jaimoe and Marc Quinones, as well as former ABB members Jack Pearson and Oteil Burbridge, plus Pat Bergeson, Bruce Katz and Lamar Williams Jr.

Tulane homecoming 1970 – Sidney Smith

To the end, Butch remained an incredibly powerful and melodic drummer whose parts defined the Allman Brothers’ classic songs as much as any guitar riff, bassline or vocal. I was on the road with Les Brers last fall and they put on excellent shows. I can barely find the words to describe my own joy at standing alongside Butch, Jaimoe and Marc again; it was like coming home to something very special and indescribable. It was a physical sensation as much as anything; something I felt deep in my bones and which gave me a feeling that I couldn’t have known I missed so much until I felt it again. I wish every one of you could have watched an Allman Brothers show from the side of this percussion powerhouse. It was an overwhelming experience and one that helped you understand the very deep, profound impact the drummers had on the greatness of the music.

Butch and Duane, Piedmont Park Atlanta, 1969.

Butch was irascible. He could be grumpy. He was also very bright, well versed in all manners of things. And he delighted in talking about it all. In March 2015 we spent a lot of time together over one weekend when he was doing some events in New Jersey and I drove him around while we talked in depth about anything and everything. I heard some wild Allman Brothers stories for the first time; maybe he figured they were safe to let out now that the book was done!

Bothers forever. Photo by Derek Trucks during final Allman Brothers band rehearsals, October 2014.

He came to my house for breakfast with my family in great spirits and was extremely kind and gracious to my wife and children. He also engaged my Uncle Ben, Dartmouth grad and retired judge, in an in-depth conversation about their shared passions for philosophy and physics. He was impressed that my then 17-year-old son Jacob knew his philosophers and that made me very proud. Later that afternoon, we did a talk together at Words, Maplewood’s bookstore and owner Jonah Zimiles was wowed. He later told me that Butch was his favorite guest ever – and the store has hosted a cavalcade of literary stars.

My relationship with Butch first deepened over a book – and it wasn’t One Way Out. He reached out to me in 2011 after reading about my memoir Big in China in Hittin the Note magazine. He was fascinated by my story about playing music in China and our relationship deepened. Throughout the writing of One Way Out, Butch answered my phone calls and emails consistently and quickly and was always ready to share an opinion or memory. He was, in short, an invaluable resource – and he immediately agreed to write a Foreword when I asked. Then he almost as quickly wrote it by himself, straight through, and it ran with very little editing. That’s not how celebrity Forewords and Afterwords usually happen.

in Hittin the Note magazine. He was fascinated by my story about playing music in China and our relationship deepened. Throughout the writing of One Way Out, Butch answered my phone calls and emails consistently and quickly and was always ready to share an opinion or memory. He was, in short, an invaluable resource – and he immediately agreed to write a Foreword when I asked. Then he almost as quickly wrote it by himself, straight through, and it ran with very little editing. That’s not how celebrity Forewords and Afterwords usually happen.

Paul family breakfast with Uncle Butchie.

Butch played with Duane and Gregg long before the Allman Brothers Band formed in March 1969. The brothers briefly hooked up with Butch’s folk rock band The 31st of February and recorded an albumin Miami that Vanguard Records rejected. It included the first properly recorded version of “Melissa” as well as “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg’s moving tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. Musical history may have been written differently if Gregg had not flown back to Los Angeles and learned that he was still contractually bound to Liberty Records. Duane moved on to Muscle Shoals and began establishing himself as a session musician.

Eventually, Duane would appear at Butch’s Jacksonville home. He wrote in his Foreword to One Way Out:

“…there came a knock on my door and there was Duane with an incredible-looking black man. Duane, in his usual way, introduced us to each other as Jaimoe, his new drummer, and Butch, his old drummer…. He left Jaimoe at my house and, for the first time in my middle class white life I had to get to know and deal with a black man. It changed me profoundly. Over forty four years later, Jaimoe and I still best of friends and I am very proud to call him my brother.”

Three drummers – by Kirk West

Over the last four years, Butch established a wonderful, warm family vibe at his Roots, Rock Revival Camp near Woodstock. It was his baby, and Oteil as well as Luther and Cody Dickinson were the other core counselors Bruce Katz, Bill Evans, Roosevelt Collier and others also were involved. I attended the first two and they were fantastic. It’s hard to over-state what he created up there: a small but growing and fiercely loyal band of brothers and sisters.

Trucks is the third founding member of the Allman Brothers Band to leave this mortal coil and the first since Berry Oakley in 1972. Founder and guiding light Duane Allman died in 1971, of course. You either understand how I feel right now or you don’t. If you do, I offer a digital hug of brotherhood. I send my deepest condolences to Melinda, Elise, Seth, Vaylor, Chris, Duane, Derek, Melody and all other members of the bountiful and wonderful Trucks family. Condolences go out also to the entire extended Allman Brothers Band family. It’s a sad, sad day in our little world, friends.

Any media members are free to quote at will from the obituary as long as you promise to not say that Derek Trucks was Butch’s son. He is his nephew!

January 20, 2019

Gregg Allman’s haunting tribute to MLK

Every year on MLK Day I share “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg Allman’s beautiful tribute to Dr. King, which he wrote and recorded in 1968, shortly after the assassination.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Gregg Allman wrote this song for Dr. King but it was never on any of his proper releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back from Florida to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… There are multiple versions of it, and this is not my favorite but I think it’s a great tribute to a great man and the person who put this video together with pics of Dr. King did it justice, though he misidentifies it as being The Hourglass. This tracks was actually cut with Butch Trucks’ The 31st of February and produced by Alaimo.

As always, I think it’s important to remember that when Dr. King was assassinated he was in Memphis marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so. It bothers me that we have garbage pickup today. Let’s not allow MLK Day to become another excuse for sales.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

Greg Allman’s haunting tribute to MLK

Every year on MLK Day I share “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg Allman’s beautiful tribute to Dr. King, which he wrote and recorded in 1968, shortly after the assassination.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Gregg Allman wrote this song for Dr. King but it was never on any of his proper releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back from Florida to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… There are multiple versions of it, and this is not my favorite but I think it’s a great tribute to a great man and the person who put this video together with pics of Dr. King did it justice, though he misidentifies it as being The Hourglass. This tracks was actually cut with Butch Trucks’ The 31st of February and produced by Alaimo.

As always, I think it’s important to remember that when Dr. King was assassinated he was in Memphis marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so. It bothers me that we have garbage pickup today. Let’s not allow MLK Day to become another excuse for sales.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

October 25, 2018

Capturing that moment when Derek got some ink

Butch and Gregg watched on and approved.

Four years ago I as honored to sit in for several of the rehearsals for the Allman Brothers band’s final shows. It was incredible then and is more incredible now, on reflection. Wow. Did that happen? Even more remarkable was being in the room when Derek Trucks decided to get the famed mushroom tattoo. I filmed the whole thing and have some really cool video that is still sitting on my laptop. I have not had time to do it justice and yes I know that’s lame. My original post about this was probably my most-viewed up here. Crazy. Reposted here, with no real edits in the text.

I was at the Allman Brothers’ second Beacon rehearsal Friday and Derek was talking to Jaimoe about getting a mushroom tattoo on his calf. Wanting to make sure that his would match the tat that all the original members received together in San Francisco in January, 1971 from pioneering tattooist Lyle Tuttle, Derek was going around photographing theoriginal member’s artwork. (Details of the Tuttle tattoos are on page 112 of One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.)

Derek and Warren have been the only members of the band ever to not receive them.

“Why are you doing this now?” I asked Derek.

“Because Jaimoe told me to and I do what Jaimoe says to do,” he replied.

I still wasn’t sure he was serious.

I arrived early on Sunday to find Jaimoe alone in the room behind his kit, with a few hard-working techs getting everything set. Gregg Allman Band keyboardist Pete Levin soon showed up, with two tattoo-artist friends. Derek was close behind. And so it began.

I asked the tattoo artist, Brian, what he thought. “Easy job,” he replied. “Somewhat intimidating setting.”

And that was before Gregg, Butch and everyone else showed up and crowded around.

The stencil

As Jaimoe stood there videoing the action with his phone, I asked him why he pushed Derek to do this now, seemingly six shows from the end of the guitarist’s Allman Brothers career.

“Young Blood told me he wanted this about two years ago and I couldn’t believe it, but no one knew an artist,” he replied.

Derek was reclining on the couch stoically watching the Jacksonville Jaguars game on his Iphone as the artist worked away. The setup had taken so long that the band members arrived one by one and strolled over to have a look. As you can see, uncle Butch and Gregg shared a moment together while this was going on. They were all quite amused and excited.

Derek watching some football as he gets inked.

I shot some classic video, which I still need to edit together and Derek says he still wants!

After Derek, several other people got the same tattoo, including Gregg confidante Chank Middleton and drum tech Stixx Turner, whom Gregg and Butch proclaimed to be the first female to be so adorned.

The Allman Brothers band’s final bow – four years ago

Four years ago today, the Allman Brothers Band played their final show at the Beacon Theatre. You can order a CD of the final show right here.

I covered the final shows every which way, posting on Facebook, covering immediately for Billboard, with a story I had to get up and write with about two hours sleep, and writing the following story for Guitar World, with a little bit of time to digest and talk to Jaimoe, Warren and Derek.

The paperback edition of One Way Out includes a full chapter on the tumultuous final year. It includes some of this material, and so much more. Click to order. If you want a signed copy, just drop me a line. Enjoy the story. It’s still emotional for me to read this!

The final bow – Kirk West

The Allman Brothers Band closed out their 45-year Hall of Fame career with six shows at New York’s Beacon Theater, October 21-28. The group’s final year was dogged by controversy. Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes announced in January they would no longer tour with the group after this year, but also said it had been a band decision, Gregg Allman and drummer Butch Trucks sent mixed signals about whether the band was really retiring. The group had to postpone four March shows at the Beacon when Gregg was physically unable to perform, and the singer also had to cancel a host of solo dates.

Yet things seemed calm as they entered the run of final shows. On the eve of the run’s first show, just before a final rehearsal on the Beacon stage, Gregg Allman stood in the theater’s lobby and seemed quite at peace with the band’s decision.

“It’s been 45 years,” he said. “I think that’s about enough.”

He also said that the group had decided not to have any of the guests who have become a Beacon staple: “There’s only six shows left and we’re going to go out with just the seven band members.”

On opening night, the theater was filled with an air of anticipation and reverence, a step beyond the normal excitement that has always met the band at the Beacon, where they have sold out 238 shows since 1989. They closed the first set with “You Don’t Love Me.” Before applause could swell, Haynes played a plaintive, almost mournful lick, which revealed itself as the melody of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Derek Trucks responded with a sacred slide wail, Gregg’s churchy organ fell in with them, and the whole band swooped in for a breathtaking instrumental version of the traditional American song of mourning, which always played a special role in the Allman Brothers and which the group played at Duane Allman’s funeral.

The next night, the guitarists again started an instrumental “Circle,” this time offering up a more jagged, aggressive reading in the jammed out coda of “Black Hearted Woman.”

Derek McCabe photo

Before the third show, on Friday October 24, Duane’s two Gibson Les Pauls, a cherrytop and darkburst, arrived from the Rock and Roll of Fame. (See this story for full details.) They joined the 1957 Les Paul which Derek had been intermittently playing since the first show, marking the first time Duane’s three primary guitars were all together, and their presence seemed to animate the band, who played their best show since the 40th anniversary performance of March 26, 2009. The surge of energy was testament to the remarkable power Duane exerted on the Allman Brothers Band until the very end. Trucks and Haynes’ playing took on more urgency. The two moved closer together, leaning in to better hear and respond to each note. The drummers hit with more force. Gregg Allman was fully, absolutely present, and singing with extra power and precise phrasing.

“Those guitars were inspiring to play,” says Haynes. “They are not in the greatest shape after not being played for so long, but the sound is unreal. The tone they generate is so remarkable and distinctive; it is the sound of Duane.”

During Friday’s show-ending “Whipping Post” encore, the band stopped on a dime and went into “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” again, but this time Gregg sang it, a mournful, haunting lament that led right back into the finale of “Whipping Post.” The band was flying at a very high altitude.

The Allman Brothers mostly maintained this level for two more nights, with instrumental versions of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” inserted into “Jessica” and “Les Brers in A Minor,” respectively. That left one final show, on Tuesday, October 28th. Grandiose rumors circulated: They would play four sets. They would play until sunrise, just like at the Fillmore East. They would play an hour-long “Mountain Jam.” All the hyperbole turned out to be just a slight exaggeration.

From the first notes, it was clear this was going to be a special night. The reverential, ecstatic crowd was hanging on every note, each of which was played with intent and focus. It suddenly seemed likely that the band could actually pull off Derek Trucks’ desire to go out on top of their game.

The band kicked off with a brief reading of the instrumental “Little Martha,” transitioning into a “Mountain Jam” that was little more than a tease, then launching into the first songs from their first album, “Don’t Want You No More” and “Not My Cross to Bear.”

Butch Trucks summoned the old freight train power that drove the band to their greatest heights. Jaimoe complemented his partner’s fury with swinging accents and added power. Percussionist Marc Quinones heaped coal into the furnace. Gregg Allman sang as well as he has in years, while his organ seasoned every song. The frontline of Haynes, Trucks and Oteil Burbridge pushed one another higher in an endless conversation of push-pull rhythms and interwoven parts.

“I had a good feeling from the very first night,” says Derek Trucks. “But It wasn’t really until the show started on the last night that everything seemed to fall into place and we all knew this had the potential to really become something special.”

The show largely leaned on Duane-era material, plus three songs recorded after Duane’s death but closely associated with him: “Melissa,” and “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” which were both played at his funeral, and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” which Gregg wrote in response to his brother’s death. A Haynes-sung “Blue Sky” paid unspoken tribute to founding guitarist Dickey Betts, who has not performed with the band since 2000. The only late-era song in the playlist, interestingly, was “The High Cost of Low Living.”

Derek, Duane’s goldtop. Photo- Derek McCabe

When the show ticked past midnight, the Allman Brothers were wrapping up their career on October 29, the 43rd anniversary of Duane’s death. They played an extended version of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” wrapped in the middle of a massive “Mountain Jam.”

After an encore of a high energy “Whipping Post” the band walked to center stage as the Beacon shook with applause. It was startling to see the seven members together, arm in arm, waving and bowing, because the Allman Brothers have never been a group bow type of band. Gregg has gone whole Beacon runs without saying much more than “Thank y’all,” but he took the mic and offered some eloquent words of thanks and reflection. Then he said that they would close out with the first song they ever played together. Every hardcore in the audience and there weren’t many people there who didn’t meet that description- knew what was coming next: the band’s reinterpretation of Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More.”

The whole audience sang along, leaning forward so much that it felt like the theater might tip over backwards. When the song ended, no one on stage seemed to know what to do, lingering by their instruments. Butch and Jaimoe thrust their arms in the air in triumph. Gregg stood and waved. Haynes and Burbridge embraced. Quinones walked to the front and handed drumsticks to the crowd.

The crowd remained in their seats as a slide show of the band’s history, heavy on Duane and Berry Oakley, rolled on screen to the recorded strains of the lilting instrumental “Little Martha.” It was Duane’s only composition, the notes of which decorate his gravestone. It was also the tune that began this night four and a half hours earlier. The circle was complete, unbroken.

“I think the one thing everyone who was in that room could agree on is the night happened exactly as it should have,” says Derek Trucks. “There was something really honest and pure and it was a bonafied moment, which don’t happen too often on Planet Earth.”

Jaimoe played the shows the highest Allman Brothers compliment, saying the spirit, energy, musicianship and tireless flow reminded him of the original band, that elusive gold standard every other iteration has been chasing like a ghost since 1971.

“Those dates were a lot like the original six,” he said. “We could have kept playing more nights.”

The final bow – Photo – Derek McCabe

September 11, 2018

9/11 17 years later – still raw

Reposted today, as I do every year on this date. I don’t think the words will ever be any less true. Last year, I took the whole family to visit the Flight 93 crash sight in Shanksville, PA and paid our respects. All the same feelings…

My family strolling through 9/11 Memorial, Liberty State Park on 9/11/11

Seventeen years later, 9-11 is still very, very raw to me.

In 2011, on the tenth anniversary, my whole family visited the Statue of Liberty and we went up in the crown. The security was tight. There were helicopters flying overhead. And when we got back on the ferry to leave, I looked back at the Statue of Liberty and felt as patriotic as I ever have and I thought, “She’s still here and you’re not.”

We took a family picture and we smiled because it felt good to be alive and to be together, and to feel like our way of life had not been destroyed. But we smiled with heavy hearts, because, of course, we thought about everyone who wasn’t there, everyone we all should remember on this day every year.

We came back from the Statue and walked through the very beautiful memorial in Jersey City, in Liberty State Park. I walked through it silently, looking at the names etched on the side: husbands, wives, daughters, sons, lovers, friends who never came home. And I wept to myself.

It’s still so real.

Part of me wants 9-11 to be a National holiday but I can’t bear the thought of it becoming like Memorial or Labor Day; another excuse for sales and a cooler full of beer.

I know this was a national tragedy, but I just don’t think people outside of the NYC area felt it or understood it in quite the same way as those of us who were here in the metro area. We saw the cars sitting unclaimed in the train stations. The missing posters lovingly hand written and pasted all over the city, the candles burning in front of every fire station.

At noon on 9-11, I was at the South Mountain YMCA picking up Jacob, who was 3, and helping the director go through the files looking for kids who had two parents working in Manhattan, flagging two kids whose parents both worked in the Towers. It took hours until everything sorted itself out. One little baby girl lost her mother. A father around the corner never came home.

The next day I went up to the South Mountain Reservation, walked over to the edge of the wall on the bluff overlooking downtown New York and where the towers used to be was a big grey cloud swirling around and filling the air – even here, 25 miles away – with an acrid smell.

I want to make sure my kids understand, really understand, how real this was. How real it still is to me. So I will take them up there in a few minutes to lay some flowers at the memorial. It sprouted immediately, spontaneously, and is now official, honoring our friends and neighbors who got up and went to work and never came home.

“Never forget” means a lot of things to a lot of people. I’m thinking of them.

September 9, 2018

The story behind Southern Blood, Gregg Allman’s stirring farewell album

Southern Blood was released one year ago yesterday. In honor of that and in memory of Gregg Allman, here is my story on the making of Southern Blood

was released one year ago yesterday. In honor of that and in memory of Gregg Allman, here is my story on the making of Southern Blood , originally published in The Wall Street Journal. It’s still quite an emotional read for me. It was the first time Chank spoke publicly about Gregg after his death.

, originally published in The Wall Street Journal. It’s still quite an emotional read for me. It was the first time Chank spoke publicly about Gregg after his death.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Gregg Allman had been working on “My Only True Friend” with guitarist Scott Sharrard for a few months when they met for a songwriting session in Mr. Allman’s New York hotel room in March 2014. The Allman Brothers Band was in the midst of its final year of performances, after which Mr. Allman would dedicate himself to performances with his solo band for which Mr. Sharrard was the musical director. As they settled down with acoustic guitars, Mr. Allman dropped some heavy news: He had terminal liver cancer. Though he wished to keep the news secret, it seemed to shift his songwriting ideas.

“He scratched out a line of the song and added a new one: ‘I hope you’re haunted by the music of my soul when I’m gone,’” recalls Mr. Sharrard.

With the new lyric, “My Only True Friend” transformed from a classic road song to an aching farewell to his fans. It is now the lead single and emotional centerpiece of Southern Blood

, the final solo album by Mr. Allman, who died on May 27 at age 69. The album is set for release on September 8.

, the final solo album by Mr. Allman, who died on May 27 at age 69. The album is set for release on September 8. “As soon as I heard ‘My Only True Friend,’ I thought the song was a shockingly honest confessional, that he was laying himself out and standing naked,” says producer Don Was. “He was telling you the key to his life because he wanted to tie up the loose ends for the people who had stuck with him for decades and also for himself. He was making sense of the totality of his life.

“Gregg was fully realized when he was on stage playing for his fans. What you saw on stage was the real guy and all the troubles he encountered had to do with not knowing what to do with himself the rest of the time,” Mr. Was says. “I think that’s the Rosebud of the Gregg Allman story,” Mr. Was says.

Southern Blood was recorded with Mr. Allman’s touring band at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Ala., where Mr. Allman’s brother Duane first made his name as a session musician with Wilson Pickett, Boz Scaggs and others. The band played live with Gregg Allman singing along and most of the performances on the album were captured in the first or second takes. A noted perfectionist, Mr. Allman planned to do vocal overdubs, to add his voice to two more completed musical tracks and to finish some tunes he was working on with Mr. Sharrard and keyboardist Peter Levin. Mr. Sharrard says there were also plans to write with Bonnie Raitt, Jason Isbell and others.

All of this was rendered impossible by Mr. Allman’s health struggles, so aside from “My Only True Friend” and one other Allman/Sharrard song, Southern Blood leans heavily on covers. Most of the material has an autumnal feel and underlying theme of mortality, notably Bob Dylan’s “Going Going Gone,” the Grateful Dead’s “Black Muddy River” and “Once I Was” by Tim Buckley, the California folkie who was a large and unexpected influence on Mr. Allman’s songwriting. The album closes with a duet with Mr. Allman’s old friend Jackson Browne on Mr. Browne’s elegiac “Song for Adam.”

All of this was rendered impossible by Mr. Allman’s health struggles, so aside from “My Only True Friend” and one other Allman/Sharrard song, Southern Blood leans heavily on covers. Most of the material has an autumnal feel and underlying theme of mortality, notably Bob Dylan’s “Going Going Gone,” the Grateful Dead’s “Black Muddy River” and “Once I Was” by Tim Buckley, the California folkie who was a large and unexpected influence on Mr. Allman’s songwriting. The album closes with a duet with Mr. Allman’s old friend Jackson Browne on Mr. Browne’s elegiac “Song for Adam.”“The sessions were powerful because we all knew what he was singing about and why we were there,” says Mr. Was. The producer, who has worked with the Rolling Stones, Bonnie Raitt, Van Morrison and many others, grew emotional discussing the monumental task of helping Mr. Allman achieve his dying vision.

Photo – Derek McCabe

“Even in such a heavy atmosphere, we had a lot of fun and the mood was effusive because we knew we were getting it,” Mr. Was says. “Gregg was digging in deep and he was oozing heart and soul, even in spots where he might not have had the lung power that he once had. He wanted to do vocal overdubs but honestly if he had been able to, maybe we would have cleansed away some of the soul.”

By the time of the recording sessions, in March 2016, Mr. Allman had already outlived his diagnosis by several years. In 2012, two years after undergoing a liver transplant, he learned that he had a recurrence of liver cancer and was given 12 to 18 months to live, according to manager Michael Lehman.

“The doctors said the cancer could not be cured but treatment could extend his life, but radiation treatment would have risked damaging his vocal cords and he refused, because he wanted to play music as long as he could,” says Mr. Lehman. “He wanted to enjoy his life and to perform until he simply could not.”

Mr. Allman played his final show in Atlanta on Oct. 29, 2016. As Mr. Allman rested and grew ever more ill in his Georgia home, attended by his wife Shannon, Mr. Was worked to finish the album, adding minimal overdubs. Until the end, Mr. Allman discussed his illness with just a handful of people. Chank Middleton, a friend of almost 50 years who was a near constant companion and was with him in his final weeks, says that Mr. Allman remained upbeat until almost the very end.

“I knew for a few years and it was hard for me to accept but he was the one with strong words,” says Mr. Middleton. “I never saw him stand up to anything or anyone as he stood up to death. He did not like confrontation but he faced death like a strong soldier. He looked it in the eyes and said, ‘Death, I’m not scared of you and I’m not ready for you.’”