Alan Paul's Blog, page 3

July 1, 2020

Brothers Show to Be ReBroadcast, Available for Purchase

Press Release Below. Not my words.

Surviving members of the ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND came together Tuesday, March 10 as THE BROTHERS for an acclaimed, sold-out, one-night-only show celebrating 50 years of the iconic American band’s legacy at Madison Square Garden in New York City. In partnership with nugs.net–the leading live music platform for concert recordings and live streams-the “50th Anniversary Celebration of The Allman Brothers Band’‘ is now available for purchase on nugs.tv in HD or stunning 4K, and will be rebroadcast beginning this Friday (July 3) at 8PM EST – Sunday (July 5)

Those who purchase the webcast will also be able to enjoy the show on demand for 48 hours upon first viewing. Both the video and audio have been re-edited and remixed, respectively to give home viewers the best seat in the house for this historic concert. Experience the music of The Allman Brothers in an entirely new way. Now available in Sony’s 360 Reality Audio via nugs.net Hi-Fi. Listen to The Brothers’ nearly four-hour show as if you were there. The Brothers consists of founding Allman Brothers Band (ABB) drummer Jaimoe as well as longtime ABB guitarists Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks, bassist Oteil Burbridge and percussionist Marc Quinones, along with Widespread Panic drummer Duane Trucks and keyboardist Reese Wynans. Former ABB keyboardist (and longtime touring member of the Rolling Stones) Chuck Leavell joined as a special guest for many of the jams he helped create with the ABB. The March 10 show is the last major concert to have taken place in New York before being shut down because of Covid-19.

In a post-show interview with the Wall Street Journal, Jaimoe said, “It just felt like no BS, and all about music and love…I wanted to play music with my brothers. Everyone else is paying homage to the Allman Brothers music-and some of us are still here.”

American Songwriter , (which described the show as a “massive success”) talked to Warren Haynes who said, “It was a very surreal night I think for all of us. It would have been under normal circumstances. But as we got closer and closer to show date, we were all wondering if we’re going to be allowed to play. We barely got in under the wire and then the next couple of days, they basically starting shutting down everything and canceling shows everywhere. It’s very bizarre that we turned out to be the last big show like that…I’m really glad that we were able to celebrate the 50th. When (original band member) Jaimoe called everybody and said that he thought that we should do something for the 50th, we all instantly agreed and thought, yeah, let’s do this. In a lot of ways, it was a show that we had talked about doing as the Allman Brothers Band but it never came to fruition. From the first moment of rehearsal it felt wonderful, and it just got better and better. I was very proud of everyone. From a musical standpoint, the band sounded wonderful. But there was so much more at play.”

Speaking with RollingStone.com, Derek Trucks recalled, “When we first got to New York about a week before, there were no restrictions and no one was really thinking about [the virus] too much. I was being OCD with Purell, but you eat out; you’re on the road and that’s what you do. But now a thousand things go through your head…So that felt a little weird. But information was rolling out at such a trickle that it was hard to make sense of anything…We were doing four days of rehearsals and everyone was playing that music for the first time in a while and telling stories and remembering people we’d lost. You’re kind of in two different worlds. You’re of two minds. If you postpone six or eight months, you never know how it’s going to be between now and then. But it also felt like one of the last moments for a long time when people would be able to suspend reality and let go.” As for the concert itself, Derek said, “I was really proud of everyone onstage. I thought everyone’s head was in the right place. That’s hard to do. There’s a lot of history with everyone on that stage, and you never know how that’s going to shake out. But it felt good. The spirit felt right.”

“The Brothers’ Madison Square Garden reunion show to celebrate the Allman Brothers Band’s 50th anniversary on Tuesday (March 10) was, in a word, superb. From the first note to the last in the four-plus-hour performance, the band played with urgency, intensity and creativity, breathing fire into one of rock’s greatest catalogs…With virtually no interruptions even for guitar changes and few words said, they played marvelously well together, veering effortlessly into modern jazz, deep blues and Indian ragas before falling right back onto the riff every time. It was exactly the type of tight but loose musical focus that made the Allman Brothers the best, hardest hitting improvisational rock band of all time.” – Alan Paul, Billboard , 3/11/20

“During the course of four hours – two sets separated by a half-hour break – the Brothers paid bristling homage to the Allmans legacy in what amounted to a musical wake: an inspiring and often moving send-off to a band and the genre it pioneered…the players also brought plenty of firepower, heard in fierce first-set versions of ‘Trouble No More’ and ‘Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’.’ Whether it was intended or not, the night also proved what could be a template for the future of classic rock, which is now essentially the classical music of boomers. Dead & Co. have revived the sound and audience for the Grateful Dead’s music, with original members providing a link to the past. Yet what happens when almost all the original members of an iconic lineup are gone? Who keeps the music going and how credible can it be without deteriorating into tribute-band cheesiness? At least for one night, the Brothers laid out that road map and provided hope that rock & roll may, possibly, never forget.” –David Browne, Rolling Stone , 3/11/20

The Allman Brothers Band played their first show on March 26, 1969 and went on to embark on a Hall Of Fame career, which came to a close with their final performance on October 28, 2014 at the Beacon Theatre in New York City. Brad Serling, nugs.net Founder and CEO, added, “We could not be more thrilled about the opportunity to work with The Brothers on this PPV from MSG. The music that these performers helped to create is so incredibly special. We are very thankful to be able to help share this performance with ABB fans around the planet.” More information about the Pay-Per-View can be found at https://2nu.gs/TheBrothersWebcast.

Pricing:All those who bought it the first time get it for free.Webcast: $12.99-HD | $19.99-4K | $19.99 HD+MP3 | $29.99 4K+MP3 Audio: nugs.net and The Brothers are also offering fans the ability to enjoy the audio from the show in Sony’s 360 Reality Audio. The unique format provides subscribers of nugs.net Hi-Fi the ability to hear the show as if they are there during the performance.

The Brothers’ March 10, 2020 set list:Don’t Want You No More/ It’s Not My Cross To BearStatesboro BluesRevivalTrouble No MoreDon’t Keep Me Wonderin’Black Hearted WomanDreamsHot’LantaCome and Go Blues Soulshine Stand Back Jessica Mountain JamBlue Sky DesdemonaAin’t Wasting Time No MoreEvery Hungry WomanMelissaIn Memory of Elizabeth ReedNo One to Run WithOne Way OutMidnight RiderWhipping Post About The BrothersThe Brothers are all the surviving members of the final ABB lineup: drummer Jaimoe, guitarists Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks, bassist Oteil Burbridge and percussionist Marc Quinones.Reese Wynans was a member of Second Coming, a band that pre-dated the formation of The Allman Brothers Band by just months and included Duane Allman, Dickey Betts, Berry Oakley, Butch Trucks and Jaimoe. Duane Truck is Derek’s little brother, whose uncle was ABB co-founder Butch Trucks. Duane is currently a drummer for Widespread Panic. Chuck Leavell was first heard by ABB fans on Gregg’s first solo album, Laid Back, and joined the Allmans full-time in 1973 through their first hiatus in 1976.About nugs.netFounded in 1997 as a fan site for downloading live music,nugs.net has evolved into the leading source for official live music from the largest touring artists in the world. Metallica, Pearl Jam, Phish, Jack White, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bruce Springsteen and many others distribute recordings of every concert they play throughnugs.net. The platform offers downloads, CDs, webcasts, and are the only streaming service dedicated to live music, delivering exclusive live content to millions of fans daily.nugs.net is available on iOS, Android, AppleTV, Sonos, BluOS, and Desktop. Visitnugs.net or get the app at nugs.net/app.

Photo by Derek McCabe

Photo by Derek McCabe

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "1a6853d6b343513d7831a087bba69d05";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B000001E0D,B007HOI3WE";

June 13, 2020

My complete interview with Bruce Springsteen

Bruce and Clarence at the Uptown Theater, Chicago, Illinois, 10-10-80. Photo by Kirk West. See and buy his work here.

Bruce and Clarence at the Uptown Theater, Chicago, Illinois, 10-10-80. Photo by Kirk West. See and buy his work here.I profiled Dion for The Wall Street Journal. It is in today’s paper (June 13, 2020) and available online here.

I honestly found him to be one of the most enlightened and enlightening person I’ve ever interviewed. As soon as I can clean it up a little I will post the entire interview here. The story is based around Dion’s fabulous new album Blues With Friends . It includes duets and guitar playing by Joe Bonamassa, Jeff Beck, Steve Van Zandt, Vn Morrison, John Hammond Jr., Brian Setzer… and Bruce Springsteen.

. It includes duets and guitar playing by Joe Bonamassa, Jeff Beck, Steve Van Zandt, Vn Morrison, John Hammond Jr., Brian Setzer… and Bruce Springsteen.

I thought it would be great to have a quote from one of the guests and I figured that I might as well start at the top – with the Boss. I emailed his manager Jon Landau, with whom I ‘ve had a friendly relationship since I interviewed him for One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. He has an interesting history with the ABB, which goes back to Phil Walden’s management of Otis Redding. Read the book if you want to know more about that! Jon quickly replied that he thought Bruce might be interested, and within a day or two an interview was being set up. I used a couple of nice quotes in the story, and share the entire, barely edited interview here. You need to hear a little from Dion for a little bit of context.

Thanks for reading. Please check out my three books by clicking away: Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues, and Becoming a Star in Beijing ; One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band; Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan

; One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band; Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan

**

“I had this song called ‘Hymn to Him’ I had written a long time ago, 1981 or 82 and I always thought it was strong,” Dion says. “I thought it had heart, thought it was soulful. And I thought Patti Scialfa would sound great on this. She’s the Jersey soul girl, for sure. She’s gonna rumble doll, she’s gonna make this fly. So I sent it to her. She says ‘Dion, I love it. I wanna sing on it, I hear some stuff.’ Then she starts asking me what to do and I just let her go. She came up with a vocal arrangement that’s totally her own. She kept running these vocals, almost like Phil Spector. She laid about nine vocals on and it sounded like the wind of the holy spirit or something. It captures this whole beautiful, sublime sound.

“And Bruce loves the song from the very beginning. Patti told me that he came in with his guitar. He heard a solo, and she asked if I minded him playing it and I said, ‘Hey, if I don’t have to pay him, go ahead.’ So he does this solo and, you know, he has this gravitas, this big sound, and it was just so perfect for what she did. it was a great example of how these great artists expanded my limited vision and made the songs better beyond what I could have imagined. I gotta tell you, it was like a gift. I really asked Patti to do it, and he just gave me a gift. It was like a Christmas present.”

Interview with Bruce Springsteen, conducted on the phone June 2, 2020.

“Hey, Alan! It’s Bruce!”

Hi Bruce. Thank you so much for calling. Can you hold on one second while I begin recording?

Sure.

[Gone about 10 seconds. Recording begins with mercifully no delays or glitches.]

Bruce, you there?

I’m here.

Thank you. It felt really weird to put Bruce Springsteen on hold.

[Bruce laughs a lot. Whew. My joke, which was actually a true statement, went over.]

I just hung up with Dion an hour ago and he said to tell you thank you again.

Oh, that’s great!

He told me his version of how you ended up on the song, but I’d like to hear it from you, so let’s start there and then talk about Dion.

It was really though Patti. Dion asked Patti to do something on the music and I was in the studio with her and she said, “Why don’t you put something on here if you have any ideas.” So I got to play a little guitar, which I like to do. Always like to do.

I love Dion and I have, gosh, since I heard ‘Teenager in Love’ on my mom’s radio as a small boy. That was the first thing I heard and you know we became friendly over the years and he’s just one of those guys whose artistic curiosity has never left him, which is very unusual for musicians. It usually fades, or they lose it somehow, but Dion has remained musically curious throughout his entire life and made all kinds of different kinds of records and has continued using what is probably one of the great white pop voices of all times in creative ways. That’s very inspiring.

To look to a musician who’s a generation older than you still recording vital music?

Yeah, actually older than me! [laughs] It’s fun to see people older than me now who are still artistically vibrant. [laughs] It truly is.

And the solo you played is cool and evocative, and it fits perfectly.

It was just fun! It was… Patti was really kind of producing the session, so she gave me a lot of direction as to where to go. She’s quite good at production.

Dion said that the layered vocals were completely her idea.

Yeah, totally. She went in and said, “I have this idea.” She had all these different vocal parts and it was just incredibly creative. It was really something… I didn’t know where she was going with it until she was finished and she spent quite a few hours just very carefully layering part after part after part until something really happened. It was a great day in the studio.

Was the approach you wanted to take on that solo clear to you? Did you try different approaches?

I don’t know. I picked up a Gretsch guitar, which has a tremolo bar on it. That’s what Duane Eddy played, so that defines a little bit the sound you’re going to get, where you’re going sonically, and Patti was assisting melodically and just telling me what she was hearing and I really was there supporting her. She made it easy and it was fun. It’s an incredible song and it’s really just very, very difficult to write well about that subject and not sound preachy. He just wrote a beautiful hymn.

You talked about hearing “Teenager in Love” and being so inspired as a kid. What came next? I think all of Dion’s stuff holds up incredibly well.

Oh! Yes! First of all, it all swung like crazy. You put on “Ruby Baby,” “The Wanderer, “Runaround Sue” … all of these things have a swing, you know? And then the other thing is the sax… the great great sax solos. The guy’s name is slipping my mind right now. Um…

It’s…

What was his name?

Buddy Logan.

Right! That affected me a lot, too, you know. Obviously when Clarence and I got together, and after Clarence passed away and Jake [Clemons] got in the band, I said, “These are some essential saxophone parts that you just need to know if you are going to work in our band.” The sax solos from the Dion records are certainly part of that.

I know that when you encountered Clarence, you just wanted him in the band, but do you think that’s part of you heard in your head?

Yeah, of course. You can go back in, if you look at your rock history, the use of the saxophone on the Dion records is very, very specific and incredibly well done. So when I contemplated sax on my records, yeah, I wanted those big, swinging sax solos. That sound! All of these solos.. you can hum them. They’re melodic and built from such concrete melodically. [Sings “The Wanderer” sax solo.] You can sing them and I wanted people to be able to sing Clarence’s solos. They’re formal. They are not improvisations. They’re actually quite formal. That just, I don’t know, it just ingested into my music somehow.

The guys on the Dion records are incredible – Bucky Pizarelli playing rhythm guitar and Mickey Baker, lead…

Yeah!

The rhythm section is Panama Francis and Milt Hinton, top-flight jazz guys.

Yeah, and you can tell. You can tell.

Thank you very much. May I ask you one other completely obscure question?

Sure.

I wrote a biography of the Allman Brothers…

Yeah.

I’ve always heard that they were a big influence …

Oh yeah! When I had a band Steel Mill, they were a huge influence. Huge influence. The two guitars, and if you’re ever to go onto the internet and dig way, way down deep into the Steel Mill material you will eventually hear the kind of guitar playing that came out of the Allman Brothers. We had the two guitars, we did the third melodies… and actually yes I was a huge Allman Brothers fan when they hit and with the band I had at that time, which was 69-71. That was right in the wheelhouse and yeah they were a huge influence.

Thanks. That’s what I thought but I have never heard you discuss it.

Yeah. Not so much when I started making my own records, but right previously to that when I had a big, bluesy hard rock band, they were a huge influence.

Well, thanks Bruce. That was great and it will give the story a nice boost.

Of course. It was a pleasure. God bless.

Postscript: As soon as we hung up, I regretted not throwing in one more followup and asking about his experience opening for the Allman Brothers in 1971. A few days later I saw Steve Van Zandt praising Gregg on Twitter so I asked him about it, and he promptly replied, “They were great. And Duane complimented my slide playing.”

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_search_bar_position = "bottom";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "search";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "Shop Related Products";

amzn_assoc_default_search_phrase = "Bruce Springsteen";

amzn_assoc_default_category = "All";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "2078ba86ee85a94588665dead10fd43a";

Dion!

Dion!June 8, 2020

Derek Trucks – 2002 Guitar World story

I’ve been having fun digging through my archives during Lockdown. Today, to celebrate Derek Trucks’ 41st birthday, I present this 2002 Guitar world article focused on the Derek Trucks Band’s third album, Joyful Noise.

Derek with the ABB, Iowa, 2005. Foto – Kirk West

Derek with the ABB, Iowa, 2005. Foto – Kirk WestJoyful Noise (Columbia) is Derek Trucks’ third album but the first that he could bear to listen to by the time it was released.

“My first two albums were pretty

good but they didn’t seem to represent what we sounded like when they came

out,” says Trucks, who plays in the Allman Brothers Band as well as his own

group. “This one does, because we’ve settled down as a band and we had the

opportunity to put some really cool, different stuff on here. It should stand

up as a statement for a long time to come.”

The “different stuff” includes guest

vocalists whose diversity highlights the Trucks Band’s eclectic approach: soul

crooner Solomon Burke, salsa star Ruben Blades, blues belter Susan Tedeschi,

also known as Mrs. Derek Trucks, and Pakistani vocalist Rahat Fateh Ali Khan,

who sings on the mystical, ancient “Maki Madni.” The rest of the album features

five original instrumentals, where all these sounds mix and mingle with ease.

What binds it all together is Trucks’ remarkable guitar work, played solely in

open E and always with his fingers only.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

While his straight playing has come

a long way, Trucks’ slide work remains his calling card, as it has been since

he started appearing with the Allman Brothers at age 12. Now 23, his every note

radiates confidence and a distinctly off-the moment feel and he never sounds

like he’s showing off.

“You never want to play everything you know,” says Trucks, who has been just as influenced by Indian sarod master Ali Akbar Khan as by Duane Allman. “I get bored when bands sound like there’s nothing more to be revealed. Everything you play should be a choice and you should be forcing yourself to stretch out and bring the audience with you. It’s easy to fall back on the licks people want to hear in the Allman Brothers and the rest of this little world, but it’s much more of a challenge and ultimately much more rewarding to turn them on to something they think they have no desire to hear.”

GUITAR: Washburn Custom, Gibson SG ’62 reissue

STRINGS: DR .11-.46

AMPLIFER: (Derek Trucks Band) ’63 Fender Super Reverb (Allman Brothers Band) 100-watt Marshall head through Marshall reissue cabinet

ALL-TIME FAVORITE ALBUMS: Wayne Shorter, Speak No Evil; Ali Akbar Khan, Signature Series, Volume 2, John Coltrane, A Love Supreme, The Otis Redding Story, Freddie King, Ultimate Collection

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO: Wayne Shorter, Footprints Live

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "1a6853d6b343513d7831a087bba69d05";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B000001E0D,B007HOI3WE";

May 27, 2020

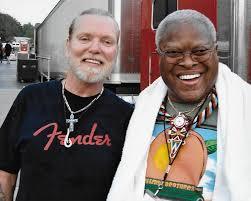

Jaimoe Remembers Gregg Allman

“There’s not anybody I ever heard who sang with more truth and passion than Gregory,” says Allman co-founder.

I interviewed Jaimoe and wrote this story for Rolling Stone after Gregg died. I was in Beijing, actually, which is why I missed the funeral, which still bums me out. I woke up at like 6 am jetlagged to speak to Jaimoe on the phone for an hour and then stayed in and wrote this. I’m really glad it got done, but I’m pretty sure I never got paid for it! So I’m reposting here on my own blog. elow is exactly what ran on RS.com.

**

News of Gregg Allman’s death from complications of liver cancer spurred an outpouring of grief and reflection across the music world. But few outside Allman’s family have been more impacted than Jai “Jaimoe” Johnson, former drummer and co-founder of Allman Brothers Band who has always been the group’s spiritual center. The musician has lost two 45-year bandmates in four months following the January suicide of drummer Butch Trucks, and is now one of just two surviving original members (Guitarist Dickey Betts has been estranged from the band since 2000, but will attend Allman’s funeral Saturday in Macon, Georgia).

A Mississippi native who toured with Otis Redding, Percy Sledge, Joe Tex and other R&B acts before the Allman Brothers Band’s formation, Jaimoe teamed with Trucks to form an unparalleled drumming duo that drove the band’s music. Rolling Stone spoke to him about the band’s formation, Allman’s legacy as a singer and songwriter and what he’ll miss most about his friend.

Gregory was the last member to join the Allman Brothers band but there never was any question that he would do so. I was the first person Duane [Allman] signed on and he told me from the very start: “There’s only one person who can sing in the band I’m putting together and that’s my baby brother.”Duane was in Muscle Shoals, Alabama working on sessions with cats like Wilson Pickett when Phil Walden, who had been Otis Redding’s manager, signed him to a deal. My friend Jackie Avery, a great songwriter, said, “Jai, I’m telling you, I ain’t never heard anyone play like this cat before.” So he drove to Muscle Shoals with a tape of songs he had written, hoping Duane might pick one or two up for his new band. I had played on the demo. Duane listened to the whole thing and Jackie said his only question was, “Who’s the drummer?”

Jackie said I should go meet and play with this guy; that he was really good and had serious backing. My friend Charles “Honeyboy” Otis had told me, “If you want to make some money, go play with those white boys.” And truthfully that’s what I was thinking of when I went to Muscle Shoals, because I had been playing on the rhythm and blues circuit and they did business “old school.” In other words, we weren’t paid jack shit but we did get our band uniforms and transportation [paid for].

I was going to New York City to pursue my dream of being a jazz drummer because I figured if I was going to starve to death, it might as well be doing something I love. But as soon as I met Duane and played with him, that all went away. It became about the music; only the music. It was the greatest music I ever played and I knew this was it. I wasn’t going anywhere without him. Two days after meeting Duane, all of my dreams came true. We didn’t have a nickel but we were all just as happy as could be, doing exactly what we wanted to do.

We went to Jacksonville and lots of people started jamming with us as Duane put together everyone he wanted for the band: Dickey Betts on guitar, Berry Oakley on bass and another drummer, Butch Trucks. We drove to Jacksonville and he knocked on Butch’s door and said, “This is Butch, my old drummer. Meet Jaimoe, my new drummer.” And then he drove away and left me there! We didn’t know what to say to each other, so Butch and I set up our drums and just started playing. We never talked about working out parts. From that moment on, we just played and it just worked. He set me up beautifully. Everything I’ve ever played that someone said was great was because Butch set me up.

We went to Jacksonville and lots of people started jamming with us as Duane put together everyone he wanted for the band: Dickey Betts on guitar, Berry Oakley on bass and another drummer, Butch Trucks. We drove to Jacksonville and he knocked on Butch’s door and said, “This is Butch, my old drummer. Meet Jaimoe, my new drummer.” And then he drove away and left me there! We didn’t know what to say to each other, so Butch and I set up our drums and just started playing. We never talked about working out parts. From that moment on, we just played and it just worked. He set me up beautifully. Everything I’ve ever played that someone said was great was because Butch set me up.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

So we had everyone there but Gregg and some people have said over the years that Duane was trying to do something different. Maybe they were fighting, but it’s not true. He told me that Gregg put a spell on women and all this stuff but there was never a doubt that he would be the singer. He was just waiting until he had all the other pieces in place before he called Gregory, who was in Los Angeles.

Reese Wynans [who went on to play with Stevie Ray Vaughan] had been playing keyboards. But Gregory finally arrived, on March 26th, 1969, and my first impression was that he looked like a television star. He was so handsome. He looked like a star actor or athlete; he was kind of a big guy – a hell of a lot bigger than Duane – who weighed 80 pounds soaking wet. But when he started singing and I heard how good he was, I wasn’t surprised. Not at all.

Duane had hipped me to what a great singer his baby brother was. It’s all he talked about, and Duane had a very specific vision in mind for the band. Everyone else he got was great and even greater together, so I figured Gregory would be the same. And he was. When the six of us got together, we became what we were looking for and who we were looking for and it was clear as a bell. It was just a great bunch of guys playing and it was just so natural. We never talked about what we were doing or told each other what to do. Everyone just played.

At that time, I really thought that there were only a few special gifted white people that could play music and I was soon to discover the reason for a lot of that was simply the fact that they were so busy imitating that they never walked out of it and into themselves. It was sitting there waiting and Gregg and Duane did that right away. Hell, the first song he sang was Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More” and he sounded great but he sounded like himself. He had that right from the first day I met him. He had been working it out for years already, even though he was just maybe 21.

I played with Otis Redding and Percy Sledge and saw Ray Charles and B.B. King and every other great and I’ll tell you this: there’s not anybody I ever heard who sang with more truth and passion than Gregory. He was at the very top of whatever what was going on with singers. And that shit about him being “one of the great white blues singer” is straight bullshit. He’s a great blues singer. A great singer, period – and those lyrics he would write were incredible. The amazing thing about Gregory Allman is the fact that his music and influences were based on rhythm and blues but his songwriting was so influenced by people like [Bob] Dylan and Jackson Browne and other people who wrote poems. Combining those two things is what made him so unique.

He came in with “My Cross to Bear” and “Whipping Post” and “Dreams” and all these great, great songs. My wife was just asking me: how does someone so young write songs so mature? I don’t know, but he did and what he influenced us to do behind was him was very unique. We were all very influenced by each other. You had no choice but to be very good at what you were doing because it was reflections of what you were hearing and everyone around us was so good! His voice and his lyrics were like two more instruments, which had a huge impact on what we played.

And Gregory was a hell of a keyboard player, too, and his great singing overshadowed his organ playing. Less is more is supposed to be a big thing now; well, he was doing it big a long time ago. What’s interesting is he could play a solo that was just eight bars, but was perfect. With what he played, he didn’t need to play no more. He could play exactly what needed to be played.

Gregg went through some hard times and had some rough periods, but he was always in the music and giving it his all. He had the Allman Brothers and he had his solo band, and he really liked the way that focused on the songs and on accompanying his singing. In 1974, he took out a band with a damn orchestra that was incredible; one of the most underrated bands ever. And I think in the last few years, after the Allman Brothers Band finished, he started getting his band right where he wanted it. My band [Jaimoe’s Jasssz Band] played quite a few shows with him over the past few years and I loved listening to him in his own group, with more focus on his singing and playing.

I will really miss playing with Gregg and hearing Gregg’s music, and I must say, those words, man. The words were as much a part of his life as the voice and they came from his life. Where else could they come from? We’re all reflections of the lives we lead. For years, I didn’t pay that much attention to his lyrics and then they hit me! So powerful. But I’ll miss the person more than anything. Yes, I’ll miss the person the most. I’ll miss Gregory very much.

As told to Alan Paul

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "1a6853d6b343513d7831a087bba69d05";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B000001E0D,B007HOI3WE";

Reflections on 25 Years Of Interviewing Gregg Allman

Today, May 27, 2020, is the third anniversary of Gregg Allman’s death.

The surprising secret at the heart of Gregg Allman’s blues-rock music: He was really a folkie soul singer.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Photo – Derek McCabeI wrote this personal reminiscence of Gregg Allman for Billboard. Re-posted here exactly as it ran.

The news of Gregg Allman’s death got me listening to his music on repeat. In that regard, today isn’t much different than any other day — just more so.

It’s hard to describe how much Gregg’s music has meant to me, as both a fan and a journalist who interviewed him dozens of times over 25 years. For me as for so many, Gregg and The Allman Brothers Band weren’t background music, and they weren’t a passing fancy. They were a touchstone to many of our lives’ happiest and saddest moments, and thus his loss resonates profoundly, like the loss of a family member.

Gregg’s easy mixing of folk, blues and rock, genres that don’t usually go together is one of the hallmarks of his music. “A certain side of me has always viewed myself as a folk singer with a rock and roll band,” Gregg told me in 1995. “I developed that perspective when I lived in Los Angeles and saw people like Tim Buckley, Stephen Stills and Jackson Browne, who was my roommate for a while. All I had known was R&B and blues and these guys turned me on to a more folk-oriented approach and it’s always stuck with me, even if a lot of Allman Brothers fans never realized it.”

Most people don’t associate Gregg with California singer-songwriters but you could hear that love of folk rock in songs like “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” and in solo numbers like “Multi Colored Lady.” Gregg was not afraid to be vulnerable, to write and sing lyrics like “Come and Go Blues” that admitted to feeling lost, betrayed, heartbroken. Even “Whipping Post,” one of his most swaggering tunes, was rooted in a heartbreak and pain so profound that good Lord, he felt like he was dying. He sang the words night after night for 45 years, with a passion that connected with people because he embraced, rather than camouflaged, his pain. When he sang you heard his father being killed when Gregg was a toddler, and his father figure, big brother Duane, dying just before his vision of the Allman Brothers Band conquering the world came true, way back in 1971.

Photo – Sidney Smith

Photo – Sidney SmithI interviewed Gregg dozens of times between 1990 and 2015 and I never quite knew what I would get. He could be thoughtful, funny and incisive, a fantastic storyteller and jovial presence, and he could be curt, just getting the job done. That’s not surprising for someone who spent a good chunk of his life picking up the phone to call reporters to advance a single show in Des Moines, Greenville or Irvine.

In 2013, I interviewed Gregg for the Wall Street Journal as he was promoting his memoir “My Cross to Bear.” It did not start out well. He was giving yes and no answers and I was scrambling to pull more out of him in our limited time. About ten minutes in, someone came to my front door and my little dog Meimei, resting at my feet, jumped up and started barking like a banshee. I was mortified, but Gregg was delighted.

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "fe826626fb5a329999a980eb734cc426";

amzn_assoc_asins = "B00XVHJWYO,0062112058,1250040507,B01HJBTI6O";

“Hey!” he exclaimed with 1,000 times more enthusiasm than he had displayed prior. “You’ve got a little kitty, too? What is she?”

“A morkie, I think. She’s a rescue dog. What do you have?”

And then Gregg went off in a rapture about his two dogs, one of whom was also a morkie, and how much he spoiled them. I knew all this, having seen him with his beloved dogs over the years.

“Gregg, I actually use you as a defense whenever someone makes fun of me having a tiny dog,” I told him, quite truthfully. “If they say it’s not manly, I just go ‘Gregg Allman has two of them!’”

Photo – Kirk West

Photo – Kirk WestHe chuckled. “I used to have giant dogs, even a St. Bernard once. I loved that dog! But you know who turned me onto little dogs? B.B. King. He told me, ‘You don’t know the love of a dog until you’ve had one who can sleep in the nook of your elbow.”

Now I had even better backup when someone made fun of my little pooch! B.B. King told Gregg Allman it was the way to go. Our interview resumed with new vigor and insight.

In 1997, I interviewed Gregg at 2 am in his Chicago hotel room after he played a solo gig at the Hard Rock Café. His then-wife Stacy and their two dogs were asleep behind us. It was a cover story for Guitar World Acoustic and I had brought an axe for him to demonstrate his finger-picked riff to “Come & Go Blues.” I handed it to him at the end of the interview, which had gone exceedingly well. It was the most relaxed, open conversation we ever had, by a long shot, which set the table for what came next.

He asked for a quarter and rounded off a couple of string ends. “You trying to take out my eye?” he inquired with a laugh. Then he re-tuned the guitar to an open tuning, took out a pouch with metal fingerpicks (which he put on) and showed me the riff, talking the whole time about how he was inspired to play in such a manner by Tim Buckley. Then he kept going, and he played and sang all of “Come & Go Blues.” Audience of one.

2009 – by Rayon Richards

2009 – by Rayon RichardsIt was an otherworldly experience, a moment where time and space were suspended and I was just right there. In that regard, it was just a heightened version of what millions experienced listening to Gregg for the last 50 years.

People talk about the concept of a musician having soul as if it were a phenomenon too complicated to grasp or explain. It is not. A performer has soul when he or she plays music because they feel compelled to do so, when he or she feels as if it is coming from another place and passing through them. Music has soul when it reminds listeners that they have one by stirring something within them, touching them somewhere deeper than their head. Music with soul doesn’t just entertain — it speaks. And it doesn’t just speak; it has something to say.

Gregg Allman had soul. Listening to him sing, you heard not just words or one-dimensional emotions, but determination, suffering, longing and love. This was in every note Gregg sang and played, because what he did is who he was. Gregg’s music was his life, his therapy, his means of expressing sadness and joy, of screaming in pain and gasping for breath. There was no wall between the artist and the art; everything he had went into his music, and the listeners understood that, even if they didn’t know it.

Alan Paul is the author of the New York Times best seller, One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "fe826626fb5a329999a980eb734cc426";

amzn_assoc_asins = "B00XVHJWYO,0062112058,1250040507,B01HJBTI6O";

May 25, 2020

Lockdown Lowdown Volume Two: Duane Betts

I’ve been doing a series of video interviews during the Lockdown. Time to share here. Volume One: The Allman Betts band’s Duane Betts.

May 15, 2020

Lockdown Lowdown Volume One: Blackberry Smoke’s Charlie Starr

I’ve been doing a series of video interviews during the Lockdown. Time to share here. Volume One: Blackberry Smoke’s Charlie Starr.

May 13, 2020

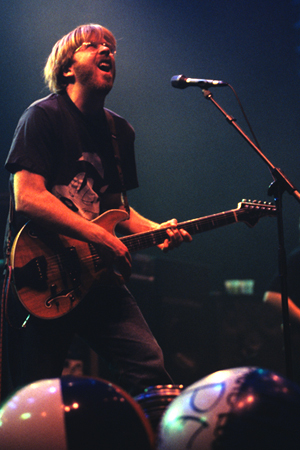

The GW Inquirer with Trey Anastasio – 1998

I completely forgot about this. In 1998, I somehow got Trey Anastasio to do a little ol’ Guitar World Inquirer, around the release of Phish’s The Story of the Ghost. Enjoy.

**

Who or what inspired you to play guitar?

If I was honest, I’d have to say Zeppelin 1, which I was obsessed with in eighth grade. I was already playing drums, and that was the album that made me want to switch because if you’re sitting behind the drum kit you can’t wear those cool dragon pants.

What was the first song you mastered?

I really only started playing guitar very shortly before Phish started and I was actually trying to learn solos before chords, starting with some of the Steely Dan songs. I think “Kid Charlemagne” was first and it was really hard. I got it some degree and then I learned “Reelin in the Years” and tried to learn the Allman Brothers’ “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

Who is your guitar hero?

Jimi Hendrix is obviously the ultimate guitar hero, mine and everyone else’s. He is without question the greatest electric guitarist who ever lived. He’s the Michael Jordan of guitar, and almost of music, really. I have tons of Hendrix bootlegs and am still obsessed with him. I have other heroes: Jerry Garcia, Frank Zappa and lots more. But Jimi had it all. How could you pick anyone else?

Is there any one gig you consider your best?

Well, I’m pretty self-critical so while I’m sure that there’s lots of live stuff that was probably really good, there’s also a lot of really bad stuff. I like some of the stuff on the live album [A Live One] and I like “Billy Breathes” and “Prince Caspian” and the solo on ”Taste,” from Billy Breathes, but I like The Story of the Ghost more. It’s just too fresh to analyze.

How about your worst gig?

We played in France, where we are totally unknown, in between Santana and Noah, an Israeli folk singer who is very popular there and got three encores. I had a really bad feeling as we walked on stage and within two minutes after we started playing the audience started whistling really loud — which is how they boo. We probably should have accepted that we had been booed off stage and walked off, but we didn’t. We went into this huge jam and in the middle of it, the whistling just went nuts. It was pretty wild We managed to play about four songs before we succumbed and walked off stage. Oddly, it was kind of one of the greatest moments in my life because it was so intense and weird standing there with all this energy raining down on us. We had rehearsed with Noah and we were going to do this whole thing with her and her manager was standing on stage screaming at her not to do it. We were trying to figure out what to say but we were afraid to say anything, though we thought of all sorts of funny things, like, “All you’re good for is your fries and your kiss” and ”This place would be Germany if it wasn’t for us.” All kinds of horrible stuff, which if we had uttered we would probably have all been killed.

What is the one piece of gear you couldn’t live without?

My custom Languedoc guitar. On previous records, I’ve used several other instruments, but on The Story of the Ghost, I didn’t use anything else, and on stage it’s exclusively the Languedoc. The guitar is just perfect for me and has everything I could ever need or want in an instrument.

Any advice for young guitarists?

Don’t eat at McDonald’s.

Any fashion tips you’d like to impart?

Yeah — don’t dress like me.

Trey, 1998

Trey, 1998 Phish, The Story of the Ghost

Phish, The Story of the GhostApril 30, 2020

The wild, insane totally true tale of Col. Bruce Hampton’s death

Photo – Jess Burbridge

A year ago today, May 1, 2017, Col. Bruce Hampton died in the most dramatic possible fashion during his 70th birthday party concert at the fabulous Fox Theatre in Atlanta. I wrote the following story for the Wall Street Journal and was pleasantly surprised to watch it be one of the most read and most shared stories on the WSJ site for days. I knew Bruce would have liked that. The whole thing is no less insane a year later.

I was pretty close to Bruce, so it was a gratifying but very difficult story to report and write. It was the second of three incredibly emotional interviews I did with Warren in just a few months, in between Butch Trucks and Gregg Allman’s deaths. Just typing that now still shakes me up!

If you want to read more:

My piece on why Bruce and the Aquarium Rescue Unit were so important is here.

And my personal tribute written in the shock of his death is here.

***

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE WALL STREET JOURNAL:

Bruce Hampton may be the only person to have died at his own wake. The guitarist/singer/bandleader collapsed on stage of Atlanta’s Fox Theater on Monday, May 1, at the climax of Hampton70, a birthday celebration featuring dozens of his acolytes, including members of the Allman Brothers Band, the Rolling Stones, Phish, Widespread Panic, REM, Blues Traveler and Widespread Panic.

The sold out show concluded with over 30 musicians on stage smiling broadly as Hampton led them through Bobby Bland’s “Turn On Your Lovelight.” He pointed to 14-year-old Brandon Niederauer to solo, then went to one knee and collapsed. The band, thinking it was a theatrical end to a celebratory night, kept playing for several minutes before they stopped and EMTs rushed on stage to try and revive Hampton.

The final show – Sidney Smith photo

“It wasn’t the first time any of us had seen him on the floor like James Brown,” says Jeff Sipe, a drummer and longtime collaborator who was conducting the musicians. “It took a minute for concern to grow.”

Hampton, who had a heart attack in 2006, was rushed to Crawford Long hospital, just a few blocks from the venue. Sipe, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi, Jimmy Herring and others were met there by a medical team who said that Hampton had suffered “a massive heart attack” and died at the venue, noting that nothing could have saved him.

“Everybody was devastated,” says Haynes, of Gov’t Mule and formerly the Allman Brothers Band. “It was one of the most epic nights of music anyone on stage or in the audience has ever experienced. To go from honoring Bruce in this amazing way to mourning him in the blink of an eye was emotionally jarring.”

One Way Out Atlanta celebration, 2014

The crowd of 5,000 chanted “Bruuuuuce” throughout the night. Hampton performed a 20-minute set at the start then joined in occasionally, mostly watching from a chair on stage. Performers ranged across generations, from the 14-year-old Niederauer, the star of Broadway’s School of Rock, to 88-year-old pianist Johnny Knapp, who recorded with Billie Holiday.

“Right before he went down, he looked me in the eye and smiled,” says Sipe. “He did the same thing to a few others. In retrospect it feels like he was saying good bye.”

The man who called himself Col. Bruce Hampton (ret.) was also an actor, appearing in 1996’s Sling Blade and the recent Here Comes Rusty with Fred Willard and as a voice in the long-running cartoon show Space Ghost Coast to Coast. He was a fixture of the Atlanta music scene since his experimental Hampton Grease Band earned him the moniker “the Frank Zappa of the South” in the late 60s. Hampton’s influence and revered place in the jam band universe stemmed from the Aquarium Rescue Unit, who performed from 1988-1993. They were akin to the Velvet Underground – a group which never sold much but had tremendous influence on others, notably Phish, Blues Traveler, Widespread Panic, and the Dave Matthews Band. ARU members Sipe, Oteil Burbridge and Jimmy Herring have gone on to play with the Allman Brothers, the Dead, Dead and Co and many others. Derek Trucks gigged with Hampton often and attributes his success as a musician and a person to the inspiration and guidance he received.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Hampton was the subject of a documentary, “Basically Frightened,” named after one of his best-loved songs.

“’Basically Frightened is a very ironic title, because Bruce was absolutely fearless,” says pianist Chuck Leavell, of the Allman Brothers and Rolling Stones, who knew Hampton for over 40 years and performed Monday. “He taught the rest of us to be musically fearless, that going places you’re nervous about will make you a better musician and a better person.”

Widespread Panic’s John Bell adds that an overwhelming sense of good will enveloped everyone at the birthday concert, including the man of honor.

“There was an incredible feeling in the building that was family reunion as much as concert,” says Bell. “Everyone rose to the occasion, including Bruce, who was playing and singing as well as I’ve ever seen him. He was in command until the last second and it was glorious to see. I believe he went from fully present in this world to fully present in another world, with very little in the middle.”

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "c54ca22b81fcd1c99563ae56af5fde72";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,B00F70AYPE,B0784F2RYJ,B00YEEUEOU";

April 27, 2020

Bad Boys, Bad Boys, What cha Gonna Do?

A Look At The Detroit Pistons Bad Boys Teams

The Detroit Pistons’ Bad Boys teams are in the news right now because of ESPN’s The Last Dance documentary about Michael Jordan’s Bulls teams. I was a major fan and watched the Pistons rise up from 87-90. I wrote this article for Slam in 1999, marking the 10th anniversary of their first title. I see some things I’d change and a lot of info I’d add, but it is what it is: a really fun read.

“I sort of came up with the whole Bad Boys thing,” Isiah Thomas says.

He’s not exactly bragging, but neither does he need to be prodded. He’s simply answering a straightforward question about the origin of the nickname and outlaw image so proudly sported by his two-time champion Detroit Pistons teams a decade ago. The name gave the team a strong identity in their quest to unseat the reigning Lakers and Celtics and hold off the surging Bulls, but it has also obscured their greatness and the ferocity of their climb to the top. Ten years later, it’s easy to forget that more than brawling brawn was behind the Pistons’ success. The 89 champs had a 63-19 record and romped through the playoffs with a 15-2 record. They were the last great team before Jordan’s royal reign, and were recently hailed by the NBA as one of the league’s 10 all-time greatest squads.

“It’s not that I or any of us wanted to be the bad guys,” Thomas insists. “We had to wear the black hats because the Celtics and Lakers were wearing the white hats. They were the good guys and all of America was rooting for them, so we just figured we’d be the guys who no one was rooting for, the bad guys.

The Bad Boys. The Pistons began to be widely referred to as such in January ‘88, after Rick Mahorn floored Michael Jordan, then took on the entire Bulls bench, including coach Doug Collins, when they came to the aid of their battered star. Collins ended up sprawled across the press table and the Pistons had shown the world that they would bow to no one.

“I don’t take any shit from anyone,” says Mahorn. “I had a lot of confrontations with a lot of people, but that was definitely one of the more significant ones that labeled us.”

The next day, the Pistons read in the paper that Jordan had called them the dirtiest team in the league and claimed they intentionally tried to hurt people. Their first reaction wasn’t exactly to sue for libel.

“I thought, ‘Here’s our opening, our chance to establish a niche,’” Thomas recalls. “You’d go to Boston Garden and everyone would talk about the mystique, then Kevin McHale, Larry Bird and Robert Parish would kill you – they beat you, not some leprechauns, but the talk distracted you. I figured we could get the same kind of thing going. We could make it work for us, or against us. I always liked the Oakland Raiders, and I wanted our image to be just like that.”

So the Pistons turned the complaints into a badge of honor and soon the whole world knew what had long been obvious to hoops freaks. From 1985, when Mahorn arrived in Detroit, until ’93, when Bill Laimbeer retired, the Pistons were fined more than $220,000, plus about $85,000 in salaries lost to suspension. The burly, 6-10 Mahorn had long been known for his bruising play and dirty tactics; early in his career with the Washington Bullets, he had teamed with Jeff Ruland to form an infamously brutal duo known as McFilthy and McNasty.

“I had great partnerships with Jeff, Bill and then Charles Barkley with the Sixers,” Mahorn says. “The truth is, they were all more talented players than me, but had a similar style, and they all thrived knowing that I was out there to watch their back.”

The 6-11, 260-pound Laimbeer was a slow-moving center and a great defensive rebounder viewed around the league as a cheapshot artist and consummate crybaby. Among those he had memorable confrontations with were Jordan, Parish, Barkley and Dominique Wilkins.

“I hated him before he was my teammate,” says Mahorn. “In fact, I hated him for most of the first year he was my teammate. I thought he was an asshole and a cheap shot artist, but then I realized that he was a straightforward dude, and he played by the rules. We all did. We didn’t go beyond the rule, but we took them to the limit and they had to change the rules because our limit was just a little bit different than most people’s. For instance, we would always give someone an extra shot after the whistle. Like Jordan or Dominique might be fouled up top on a drive, then we’d smack them on the continuation. Well, they outlawed that because of us.”

While Mahorn was more likely to get into an actual physical confrontation with someone, Laimbeer more often tormented them into blowing their top and taking a swing at him, or losing their focus.

“Laimbeer rarely hit anyone; he just drove them nuts,” says longtime Pistons announcer George Blaha. “He delighted in getting under your skin. He constantly was trying to gain not the only physical edge, but also the mental edge. If he could make you lose your concentration, then he’d won, because he never seemed to lose his cool. There would be an incident, then he could go right to the free throw line and nail them, while the other guy would often have trouble playing the rest of the game with his head on straight.”

“It was all about throwing people off their games,” says Mahorn. “I think Michael developed that baseline jumper because of us. He didn’t want any part of coming into the paint after a while. There were some teams, and some people who just couldn’t deal with us. They’d be preoccupied thinking about us instead of their game. And it could throw everyone off. Like Charles Oakley was one of the few guys who wasn’t intimidated by us at all, but he would get frustrated because of his teammates. But nothing we did was dirty; we wouldn’t try to hurt anybody; just hit them. And nobody could scare us, because we were used to it. Our best fights were with each other at practice, where we could actually land some punches.”

But while Laimbeer and Mahorn were clearly the chief instigators, they were not the lone Bad Boys. A skinny, hyperactive ferocious-rebounding forward by the name of Dennis Rodman learned well from his mentors. Easy going center James Edwards, veteran guard John Long, scoring machine Adrian Dantley and his replacement Mark Aguirre all garnered fines with the Pistons. Even consummate nice guy Joe Dumars lost his cool a few times; in 1990 he was fined $1,000 three weeks apart for fighting brothers Harvey (Washington) and Horace Grant (Chicago).

And then there was Isiah, the Pistons’ captain and little general. He may have flashed the nicest smile in NBA history and weighed in at 185 pounds soaking wet, but he was in the middle of many of the Bad Boys’ baddest moments. Says Mahorn, “Isiah was a little man who wanted to be a big man and played as if playing hard enough would make him a foot taller.”

In April ’89, Thomas showed his fighting spirit and lack of both fear and common sense when he busted his hand clocking 7-foot Bulls center Bill Cartwright in the head. Proving that this was no fluke, he slapped Lakers center Mychal Thompson the following January, drawing a $2,500 fine. Then, in April ’90, he gave new Sixers center Rick Mahorn a taste of his own medicine when he audaciously punched him, despite being outweighed by nearly 100 pounds.

“I didn’t back down to anyone,” Thomas says today with a slight laugh. “Looking back now, I’m lucky I didn’t get hurt –those guys are a lot bigger than me. I don’t think I played cheap, but I definitely played hard. I’d most like to be remembered as a guy who just did whatever it took to win –whether that meant scoring 40 and looking pretty or digging in my heels and playing ugly. You can say a lot of things about me, but you can’t say I’m not a winner. And that goes for the whole team; we thought we should have won the title in ’88 and by the next season, we were prepared to do whatever it took. I think our toughness was mental as well as physical.”

Thomas is undoubtedly right, but mental toughness doesn’t leave black and blue marks, so it doesn’t tend to be quite as noticed.

“You felt it when you played them, because the whole team was incredibly physical,” recalls Chris Mullin. “It’s not that they were all dirty, but they gave you nothing. They all put their bodies on you and made you work for every little thing.”

That aggressive, never-give-an-inch defensive presence became Coach Chuck Daly’s trademark. But it wasn’t always so. In his early years, the Pistons were a high octane, running team built around Thomas and small forward Kelly Tripucka. This version of Daly’s team reached its peak early in his first season, when his Pistons defeated the Nuggets 186-184 in three overtimes in the highest scoring game in NBA history. His philosophy changed as he worked to make the best use of his players’ talents.

“I found that our club was only good when we were making contact with people,” Daly recently recalled. “We were not a very good defensive team when we weren’t right up on people. We could only be the kind of team we wanted to be when we got right up, because we weren’t quick enough to chase people around. We couldn’t let the Kevin McHales or Patrick Ewings get position before they received the ball or they would destroy us. We became a better defensive team when we created an atmosphere for our players to understand that, and they started to really believe that was how we could win.”

Mahorn seconds Daly’s assessment. “We knew how to play basketball and it was obvious that the physical style was what we needed to do to win,” he says. “I mean, we weren’t athletic. Well, the backcourt was, but up front you had these big old lugs that basically were old school. That’s all we were really doing is bringing old-fashioned style ball into the modern NBA. It was nothing new.”

“The toughness defined the team, but we should have won three titles and could have won four,” says Blaha. “And the reason is talent. We had a Hall of Fame coach; two Hall of Fame guards in Isiah and Joe; two guys who should be in the Hall but may never go because of their personalities in Laimbeer and Rodman; a great-scoring small forward whether it was Dantley or Aguirre; one of the toughest guys ever to play in Rick; and one of the most explosive bench players of all time in Vinnie.”

“They had great talent to go with their physical presence,” Mullin recalls. “Don’t forget how good Isiah and Joe were – and then they had Vinnie coming off the bench. That was deep. And they were all interchangeable; they could shoot or handle, play the point or the off-guard. That was actually an aspect of their game copied at least as much as their physicality.”

Nonetheless, the Pistons’ enduring legacy remains physical, defense-dominated play. “It was all finesse and scoring before those guys started winning,’ says Anthony Mason, spitting out the word “finesse” as if it tastes like excrement. “They just put their bodies on people, and showed you could have success that way, too.”

“Look at basketball today—low scoring, lots of physical defense. That was all the Pistons’ doing,” Laimbeer said a few years ago. (He’s apparently too busy folding cardboard boxes at his Piston Packaging company to return our calls these days.) “When we were winning, people moaned how we were ruining basketball. Actually, we sort of defined its future.”

Thomas wanted to alter his own place in history, as well as that of the team, by putting the Bad Boys name to bed after the first title. He proclaimed it dead on their White House visit and again in his book Bad Boys!, which he apparently thought would be the last time anyone cashed in on the name. But it wasn’t to be. The NBA’s marketing geniuses realized they had a horse to flog, so a video was forthcoming, cleverly titled Bad Boys. And even without Mahorn, whom they had left exposed in the expansion draft, where the Timberwolves snagged him and traded him to the Sixers, the Pistons displayed plenty of swagger and bad attitude.

One of Laimbeer’s finest –and baddest – moments came in Game Three of the 90 finals. Tied at one-one and heading to Portland, where they had lost 20 straight games, the Pistons were in trouble, with Rodman injured and Johnson in a terrible slump. But Laimbeer set the tone for a fired-up team when he ran over a photographer, who stepped in front of him in the tunnel before the game, then ran over the Blazers. He drew five quick charges and the Portland players became so preoccupied crying to the refs about Laimbeer’s flopping that they lost their minds and collapsed, 121-106. Laimbeer fouled out with 12 points and 11 rebounds, but he had turned the tide in a series the Pistons would proceed to win with two more straight road victories. “Only Bill can be like that,” Daly said after the game. “He was unbelievable.”

The following season, the Pistons were still a very good team, but were no longer dominant. They went 50-32, finishing 11 games behind the Bulls, whom they met in the Eastern Finals. With his Bulls up 2-0, Jordan declared that the reigning two-time champs were “thugs” and “bad for the NBA.” He complained about their physical style and the league’s refusal to do anything about it. The Bulls went on to sweep the Pistons and after Game 4, played at the Palace, Thomas, Laimbeer and the rest of the Bad Boys walked off the court without shaking hands with their conquerors. The Bulls had gone to the foul line three times to every one visit for Detroit, leading the Pistons to believe Jordan’s “whining” had denied them a shot at their third consecutive title. The team would never again return to the conference finals, making their refusal to shake hands with Jordan and company their final, lingering image on the national stage.

“Bad sportsmanship is bad sportsmanship, so I can’t defend what we did, but that’s how it was done then,” Thomas says. “All the rivalries were too heated, so none of us shook at the end of series. The Celtics didn’t shake our hands when we finally beat them in ’88, except for Kevin McHale, whom I had known since high school. The thing is, we got caught, because we were transitional; that’s when basketball went from being watched by just serious fans of the game to everyone. It became popular entertainment, so the rules changed.

“I’m not proud of what we did, but I’m not really ashamed of it either. I just hope that people remember that we weren’t just bad; we were also pretty damned good.”