Alan Paul's Blog, page 4

March 26, 2020

Happy Birthday Allman Brothers Band!

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "banner";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_placement = "assoc_banner_placement_default";

amzn_assoc_campaigns = "musicandentertainmentrot";

amzn_assoc_banner_type = "rotating";

amzn_assoc_p = "48";

amzn_assoc_width = "728";

amzn_assoc_height = "90";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "4fa5cd5d187de723ceba695c3bff93af";

It’s March 26, 2020. Happy 51st birthday Allman Brothers Band! Let’s celebrate with an excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band detailing their formation.

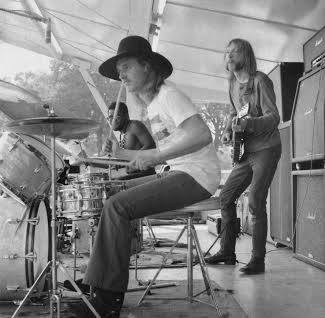

1969, new to Macon. Photo – Twiggs Lyndon

DICKEY BETTS: It says a lot that Duane’s hero was Muhammad Ali. He had Ali’s type of supreme confidence. If you weren’t involved in what he thought was the big picture, he didn’t have time for you. A lot of people really didn’t like him for that. It’s not that he was aggressive; it was more a super-positive, straight-ahead, I’ve-got-work-to-do kind of thing. If you didn’t get it, see you later. He always seemed like he was charging ahead and it took a lot of energy to be with him.

THOM DOUCETTE: I couldn’t get enough of that Duane energy. If Duane put out his hand to you, you had a hand. There was no bullshit about him at all. None.

GREGG ALLMAN: My brother was a real pistol. He was a hell of a person… a firecracker. He knew how to push people’s buttons and bring out the best.

JOHNNY SANDLIN: He was a personality you only see once in a lifetime. He could inspire you and challenge you, with eye contact, smiles… little things. It would just make you better and I think anyone who ever played with him would tell you the same thing. You knew he had your back, and that was the best feeling in the world.

BUTCH TRUCKS: One day we were jamming on a shuffle going nowhere so I started pulling back and Duane whipped around, looked me in the eyes and played this lick way up the neck like a challenge. My first reaction was to back up, but he kept doing it, which had everyone looking at me like the whole flaccid nature of this jam was my fault. The third time I got really angry and started pounding the drums like I was hitting him upside his head and the jam took off and I forgot about being self conscious and started playing music and he smiled at me, as if to say, “Now that’s more like it.”

It was like he reached inside me and flipped a switch and I’ve never been insecure about my drumming again. It was an absolute epiphany; it hit me like a ton of bricks. I swear if that moment had not happened I would probably have spent the past 30 years as a teacher. Duane was capable of reaching inside people and pulling out the best. He made us all realize that music will never be great if everyone doesn’t give it all they have and we all took on that attitude: why bother to play if you’re not going all in?

REESE WYNANS: Dickey was the hottest guitar player in the area, the guy that everyone looked up to and wanted to emulate. Then Duane came and started sitting in with us and he was more mature and more fully formed, with total confidence, an incredible tone and that unearthly slide playing. But he and Dickey complemented each other – they didn’t try to outgun one another – and the chemistry was obvious right away. It was just amazing that the two best lead guitarists around were teaming up. They were both willing to take chances rather than returning to parts they knew they could nail and everything they tried worked.

RICHARD PRICE: Dickey was already considered one of the hottest guitar players in the state of Florida. He was smoking in the Second Coming and always had a great ability to arrange.

WYNANS: I remember one time Duane came up to me with this sense of wonder and said, “Reese, I just learned how to play the highest note in the world. You put the slide on the harmonic and slide it up and all of a sudden it’s birds chirping.” And, of course, that became his famous “bird call.” He was always playing and pushing and sharing his ideas and passions.

JAIMOE: Duane had talked about a lot of guitar players and when I heard some of them I said, “That dude can’t tote your guitar case” and he was surprised. He loved jamming with everyone.

DOUCETTE: None of them could hold Duane’s case except Betts.

JAIMOE: Duane loved guitar players. I only knew two people Duane didn’t like: Jimmy Page and Sonny Sharrock. He played on the Herbie Mann Push Push sessions [in 1971] with Sonny and he hated him and the way nothing he played was ever really clear. He also didn’t like Led Zeppelin, though I don’t know why. Anyhow, Duane liked Dickey and the two of them clicked and started working on songs and parts immediately.

WYNANS: Berry was very dedicated to jamming and deeply into the Dead and the Airplane and these psychedelic approaches and always playing that music for us – and it was pretty exotic stuff to our ears, because there were no similar bands in the area. Dickey was a great blues player with a rock edge; he could play all these great Lonnie Mack licks, for instance. And then Duane arrived, and was just on another planet. And the power of all of it combined was immediately obvious.

Photo – Twiggs Lyndon

BETTS: All of us were playing in good little bands, but Duane was the guy who had Phil Walden — Otis Redding’s manager! — on his tail, anxious to get his career moving. And Duane was hip enough to say, “Hey, Phil, instead of a three-piece, I have a six-piece and we need $100,000 for equipment.” And Phil was hip enough to have faith in this guy. If there was no Phil Walden and no Duane Allman there would have been no Allman Brothers Band.

The unnamed group began regularly playing free shows in Jacksonville’s Willow Branch Park, joined by a large, rotating crop of musicians. They went on to play in several local parks.

PRICE: It was Berry’s idea to play for free in the parks for the hippies.

TRUCKS: The six of us had this incredible jam and he went to the door and said, “If anyone wants to leave this room they’re going to have to fight their way out.” We were playing all the time and doing these free concerts in the park and we all knew we had something great going, but the keyboard player was Reese Wynans not Gregg and we didn’t really have a singer. Duane said, “I need to call my baby brother.” I said, “Are you sure?” Because he was upset that Gregg had stayed out in L.A. to do his solo thing and I was upset that he had left when I thought we had something going with the 31st of February project the year before. He said, “I’m pissed at him, too but he’s the only one strong enough to sing with this band.” And, of course, he was right. Whatever his issues, Gregg had the voice and he had the songs that we needed.

PHIL WALDEN, original ABB manager; founder/president of Capricorn Records: They had this great instrumental presence but no real vocalist. Berry, Dickey and Duane were all doing a little singing. That was a lot of a little singing and no singer. So Duane called Gregg and asked him to come down.

JAIMOE: Duane was talking about Gregory being the singer in the band from the beginning. Very early on, Duane told me, “There’s only one guy who can sing in this band and that’s my baby brother.” He told me that he was a womanizer. He said Gregg broke girls hard and all the rest of it, but that he’s a hell of a singer and songwriter – which obviously was accurate and is to this day.

LINDA OAKLEY: We were all sitting in our kitchen late one night after one of these jams. They were all so psyched about what they were building and Duane said, “We’ve got to get my brother here, out of that bad situation. He’s a great singer and songwriter and he’s the guy who can finish this thing.”

WYNANS: For quite a while, we were all just jamming and guys from other bands would often be there singing, or Berry would sing, Duane would sing a little, “Rhino” Reinhardt would sing. [Guitarist Larry “Rhino” Reinhardt, who was in Second Coming and went on to play with Iron Butterfly.] Then all of a sudden there was talk of this becoming a real band, and Duane was talking about getting his brother here to sing. Everyone was excited about it, but I knew Gregg played keyboards and figured that might be the end of it for me. It was personally disappointing, because the band was really going somewhere and obviously had a chance to do something great. It was kind of a drag but this was Duane’s brother, so what can you say? You wish them good luck and move on to the next thing. It was a thrill to be a part of.

BETTS: We had all been bandleaders and we knew what we now had.

Gregg was still in Los Angeles, having stayed there after the breakup of Hour Glass. Liberty Records had recorded and released a second album with Gregg backed by session musicians after Duane, Sandlin and the rest of the band left California.

ALLMAN: I didn’t have a band, but I was under contract to a label that had me cut two terrible records, including one with these studio cats in L.A. They had me do a blues version of Tammy Wynette’s “D-I-V-O-R-C-E,” which can’t be done. It was really horrible. I hope you never hear it. They told us what to wear, what to play, everything. They dictated everything, including putting us in those clown suits. I hated it, but what are you gonna do when they’re taking care of all your expenses? You end up feeling like some kind of kept man and it was fuckin’ awful. I was excited when my brother called and said he was putting a new band together and wanted me to join. I just wrote a note that said, “I’m gone. If you want to sue my ass, come on after me.”

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "69349205923359aa5fbe86c03b0f445c";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,B00F1W0RCS,B074HYF8M6,0062112058";

BETTS: We were all telling Duane to call Gregg. We knew we needed him. They were fighting or something, which they did all the time – just normal brotherly stuff.

JAIMOE: Duane finally called Gregg when he got everyone that he thought would work, because he needed to give him as much time as possible to resolve the contract issues with Liberty. Once everyone else was in place, Duane called him and said, “You’ve got to hear this band that I’m putting together. You need to be the singer.”

KIM PAYNE, one of the ABB’s original roadies: I met Gregory in LA when I was working for another band that played with him and we became good friends, running around, staying with chicks until we got kicked out and drinking cheap wine. Almost every day we were together, Gregg would bitch about his brother. He’d say, “He’s calling me again asking him to join his band, but there ain’t no way because I can not get along with my brother in a band.” He said that to me countless times.

JON LANDAU: When I was in Muscle Shoals I was sitting in the office with Duane, Rick and Phil and Duane picked up the phone, dialed a number and said, “Brother, it’s time for us to play together again.” I was a fly on the wall and could obviously only hear one end of the conversation, but it seemed very positive.

ALLMAN: My brother only called me one time and I jumped on it.

JOHN McEUEN: As I recall, Duane kept calling Gregg saying, “You got to get down here. The band has never sounded better.” He called enough times and Gregg went. I have to give Duane credit for having the vision to do this thing. I know the L.A. years were not great ones for them, but I think it was something they had to go through to discover their path.

PAYNE: Gregg kept telling me, “I’m not going down and getting involved with that.” You have to remember he was coming off a very bad band experience; he hated the way the Hour Glass went and how it ended up and he may have connected that with being Duane’s fault. I think he also felt like Duane and the other guys turned on him and blamed him for staying in LA, when he thought he had to.

SANDLIN: It kind of bothered me that Gregg stayed out in LA, but I didn’t know if he wanted to, or was being forced by management.

PAYNE: At the same time, he was looking at his future – he was driving an old Chevy with a fender held on with antenna wire. Whenever we ran out of money, he’d go down and sell a song. We were living hand to mouth.

ALLMAN: My brother said he was tired of being a robot on the staff down in Muscle Shoals, even though he had made some progress, and gotten a little known playing with great people like Aretha and Wilson Pickett. He wanted to take off and do his own thing. He said, “I’m ready to get back on the stage, and I got this killer band together. We got two drummers, a great bass player and a hell of a lead guitar player, too.” And I said, “Well, what do you do?” And he said, “Wait’ll you get here and I’ll show you.”

I didn’t know that he had learned to play slide so well. I thought he was out of his mind, but I was doing nothing, going nowhere. My brother sent me a ticket, but I knew he didn’t have the money, so I put it in my back pocket, stuck out my thumb on the San Bernardino Freeway and got a ride all the way to Jacksonville, Florida – and it was a bass player I got a ride from.

PAYNE: I know that Gregg remembers hitchhiking across the country, but the thing is, I’m the guy who drove him to the airport.

McEUEN: My brother bought a Chevy Corvair for Gregg to drive around LA – the most unsafe car ever invented. One day Gregg comes by the house, a little duplex in Laurel Canyon, looking for my brother, who wasn’t there. He said, “Hey, John, the man pulled me over. You know how they are. He doesn’t believe this is my car and is going to impound it. I got to take the pink slip to the judge.” So I said, “I know where the pink slip is.” I gave it to him and he took it and sold that car and bought a one-way ticket to Jacksonville. Maybe I’m responsible for the Allman Brothers Band! Gregg came back about six years later when the Brothers were playing the Forum, and gave my brother a check for the car.

TRUCKS: I don’t know how he got there but a few days after Duane said he was calling Gregg, there was a knock on the door and there he was.

ALLMAN: I walked into rehearsal on March 26, 1969, and they played me the track they had worked up to Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More” and it blew me away. It was so intense.

BETTS: Gregg was floored when he heard us. We were really blowing; we’d been playing these free shows for a few weeks by that point.

ALLMAN: I got my brother aside and said, “I don’t know if I can cut this. I don’t know if I’m good enough.” And he starts in on me: “You little punk, I told these people all about you and you don’t come in here and let me down.” Then I snatched the words out of his hand and said, “Count it off, let’s do it.” And with that, I did my damnedest. I’d never heard or sung this song before, but by God I did it. I shut my eyes and sang, and at the end of that there was just a long silence. At that moment we knew what we had. Duane kinda pissed me off and embarrassed me into singing my guts out. He knew which buttons to push.

The group played their first gig on March 30, 1969 at the Jacksonville Armory. Gregg had been in town for four days.

Excerpt adapted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. Copyright 2014 Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_search_bar_position = "bottom";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "search";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "Shop Related Products";

amzn_assoc_default_search_phrase = "Allman Brothers t shirt";

amzn_assoc_default_category = "All";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "f5efca6b98abda1c0a8e25e429f91f33";

March 24, 2020

The Brothers 3/10/20 – A review

I reviewed the Brothers March 10, 2020 Madison Square Garden for Billboard. Because it is behind a paywall. I am sharing again here. All photos by Derek McCabe.

The Brothers’ Madison Square Garden reunion show to celebrate the Allman Brothers Band’s 50th anniversary on Tuesday, March 10 was, in a word, superb. From the first note to the last in the four plus hour performance, the band played with urgency, intensity and creativity, breathing fire into one of rock’s greatest catalogs.

Photo by Derek McCabe

Photo by Derek McCabeThe

group was centered around the five surviving members of the Allman Brothers’

last and longest lasting lineup, which played together from 2000 until their

final show, at New York’s Beacon Theater, on October 28, 2014: guitarists Derek

Trucks and Warren Haynes, bassist Oteil Burbridge, percussionist Marc Quinones,

and drummer Jaimoe, the only founding member on stage. (Dickey Betts is the

only other survivor and he has not played with the band since 2000 and was not

in New York.)

The

2017 deaths of drummer Buch Trucks and organist/singer/namesake Gregg Allman

left gaping holes, which were filled by Duane Trucks, Butch’s nephew and Derek’s

brother; organist Reese Wynans; and pianist Chuck Leavell, the Rolling Stones’

musical director for the last 30 years who made his first mark with the Allman Brothers

from 1973-76. Wynans is best known for his work with Stevie Ray Vaughan and

Double Trouble, but played in the nascent Allman Brothers before Gregg arrived

in Florida in 1969.

The

eight musicians welcomed no other guests, with Leavell playing about half of

each set. With virtually no interruptions even for guitar changes and few rods

said, they played marvelously well together, veering effortlessly into modern

jazz, deep blues and Indian ragas before falling right back onto the riff every

time. It was exactly the type of tight but loose musical focus that made the

Allman Brothers the best, hardest hitting improvisational rock band of all time

Photo – Derek McCabe

Photo – Derek McCabeThey

started the night with the first two songs on the Allman Brothers’ 1969 debut,

“Don’t Want You No More” and “It’s Not My Cross to Bear” and stayed focused on

the classic material from the band’s first four albums for much of the night. The

first 90s era song was Haynes’ “Soulshine” late in the first set, which kicked

off with a gospel-y piano and organ duet. The first set ended with “Jessica,”

with Leavell playing his signature licks on a grand piano sent the garden crowd

into a frenzy. Quinones turned from his percussion kit to play the timpani, one

of Butch Trucks’ signature moves, and bring the first set to a thunderous

close.

The

second set started with the timpani again, as the familiar refrains of “Mountain

Jam” rang across a dark stage. Like most of the night, the song was played at

the original, faster tempo. Leavell sang a great version of “Blue Sky,” the

only song Haynes did not sing and the only Betts vocal of the night.

“Desdemona,” the only song they played from 2005’s Hittin the Note album

had a beautiful jazz interlude, and the third and last late-era song, “Nobody

Left To Run With” led into a set-ending “One Way Out.”

Coming

back for the encores, Jaimoe took the microphone and said a few words of

thanks, before they closed out with “Midnight Rider” and “Whipping Post.”

Throughout

the night, the center focus was on Haynes and Trucks’ guitar partnership, which

was in perfect sync, but really it was all about tight ensemble playing, with

the musicians locked and loaded and playing all night as if their lives

depended on it. It was impossible to know what to expect of this lineup, or the

decision to play at MSG instead of the band’s familiar and most cozier confines

of the Beacon – and it was almost immediately impossible to doubt any of it.

The

specter of COVID-19 hung over the show, with most attendees questioning their

choice in the hours before, and word of a flood of cheap tickets online. But

the arena was packed and it was rocking. If this is the last concert we attend

for a while, no one who was in the house is going to complain.

As

Reese Wynans said after the show, “That felt historic and beautiful.”

Alan

Paul is the author of

One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band

Photo – Derek McCabe

Photo – Derek McCabe

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_search_bar_position = "bottom";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "search";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "Shop Related Products";

amzn_assoc_default_search_phrase = "Allman Brothers t shirt";

amzn_assoc_default_category = "All";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "f5efca6b98abda1c0a8e25e429f91f33";

March 18, 2020

Jaimoe Profiled in the WSJ

I profiled Jaimoe for the Wall Street Journal and their Weekend Confidential feature last week. Because many were blocked from seeing it by the WSJ firewall, I am sharing again here. Stay safe everyone.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Jaimoe Still Revels in ‘Music and Love’ The 75-year-old drummer from the Allman Brothers Band is keeping its legacy alive

By Alan Paul March 13, 2020

‘When Jaimoe tells you to do something, you do it!”

That’s guitarist Derek Trucks, explaining why a phone call from the drummer for the Allman Brothers Band started the process of a reunion show almost six years after the group played their last show in 2014. The show Tuesday in New York City was billed as a concert by the Brothers and built around the surviving core of the group’s last and longest-lived iteration. Jaimoe was the only founding member on stage.

“I wanted to play music with my brothers,” he says, explaining why he jump-started the idea of celebrating the band’s 50th anniversary. “Everyone else is paying homage to the Allman Brothers music—and some of us are still here.”

Jaimoe at ‘The Brothers: Celebrating 50 Years of the Allman Brothers Band’ at Madison Square Garden, New York City, March 10.PHOTO: DEREK MCCABE

Jaimoe at ‘The Brothers: Celebrating 50 Years of the Allman Brothers Band’ at Madison Square Garden, New York City, March 10.PHOTO: DEREK MCCABEMadison Square Garden was packed for the show, despite mounting Covid-19 fears that created a surreal preshow atmosphere. It vanished almost as soon as the first notes were played. Jaimoe, who was for so many years hidden on the Allman Brothers’ back line, was the featured star, walking slowly across the stage at the start of the show to rapturous applause and taking the microphone by himself to thank the crowd before the encore four hours later.

“It just felt like no BS, and all about music and love,” an exhausted Jaimoe, 75, said the next morning from the back seat of a car heading home to Connecticut. He had back surgery in December and worked for months to be ready to play.

Jaimoe was born Johnie Lee Johnson in Ocean Springs, Miss., and was known as Jai Johnny until Rudolph “Juicy” Carter, a saxophonist, affixed a new nickname in the late 1960s. “He kept saying, ‘Hey Jaimoe,’ and I was looking around to see who he was talking to, and he stuck his finger in my chest and said, ‘Jaimoe!’” the drummer recalls. The name stuck.

I have written a book about the Allman Brothers (for which Jaimoe wrote an afterword), have longstanding relationships with many of them and even formed a tribute band to play their music. Over the years, I’ve seen Jaimoe’s character up close. I’ve watched him treat a hotel janitor or a backstage security guard the same way he treats a bandmate; listened to him patiently discuss a fan’s favorite Allman Brothers show; seen him hobble on a bad knee after a breakfast buffet server to give her a tip; and observed him slipping money to a young drummer at a music festival with a vintage kit in need of repair.

‘I figured if I’m going to starve playing music, it might as well be the music I love,’ says Jaimoe.PHOTO: JOSH WOOL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

‘I figured if I’m going to starve playing music, it might as well be the music I love,’ says Jaimoe.PHOTO: JOSH WOOL FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNALJaimoe is the through line from the Allman Brothers’ 1969 formation through two breakups and two reunions to their final show to this week’s show in New York. The drummer was also the first person that guitarist Duane Allman asked to join his fledgling group in 1969. Jaimoe, who had toured with soul singers Otis Redding, Joe Tex and Percy Sledge, was about to move to New York to try his hand at playing jazz.

“I figured if I’m going to starve playing music, it might as well be the music I love—jazz. Then I jammed once with Duane and all those thoughts vanished,” says Jaimoe.

Still, his passion for jazz helped form the nascent Allman Brothers Band’s improvisational approach, which incorporated blues, country and Western swing into a unique musical approach that nodded toward the Grateful Dead’s West Coast explorations but never became as loosey-goosey.

“Music is music, and there’s no such things as jazz or rock ’n’ roll,” Jaimoe says. “I wanted to be the world’s greatest jazz drummer, and I thought rock or funk were too easy—then I got a chance and couldn’t play what needed to be played. I had to learn, and music was everything to me.”

Like the Dead, the Allman Brothers featured two drummers, an idea that Jaimoe says Duane Allman took from James Brown. The guitarist instinctively knew that Butch Trucks (Derek’s uncle) and Jaimoe were the pair he needed. They met when Mr. Allman dropped Jaimoe off at Mr. Trucks’s Jacksonville doorstep and drove away.

Madison Square Garden was packed for Tuesday’s show, despite mounting Covid-19 fears.PHOTO: DEREK MCCABE

Madison Square Garden was packed for Tuesday’s show, despite mounting Covid-19 fears.PHOTO: DEREK MCCABE“We took the drums inside, set them up and just started playing—and it worked,” Jaimoe recalls. “We just listened to one another and played. Butch was a great drummer. Almost everything I’ve ever played that someone said was great was a reaction to something he played.”

Jaimoe describes the early years of the Allman Brothers as “just the greatest thing in the world,” with like-minded musicians learning from each other, feeding off each other, constantly exposing one another to new ideas and spurring each other to heights beyond what any of them could have imagined on their own.

“It was like having your masters and working on your doctorate—and you’re doing it with Einstein,” he says. “It was going great, so we didn’t think about what would happen in a month. I think Duane did. He always had a vision, but I had no other thoughts except how great the music we were playing was. The whole world closed out.”

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "5f150e0a68df7132fb5f33c2442fc956";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B006OC3WRG,B00AY0MUDQ";

Shortly after its 1969 formation, the group moved together to Macon, Ga., where they lived communally, five longhair whites and one African-American drawing stares and hostility, which only formed a deeper bond. Duane died in 1971 and bassist Berry Oakley the following year in eerily similar motorcycle crashes, yet the Allman Brothers Band kept pushing on. Butch Trucks and Gregg Allman both died in 2017.

Jaimoe has lived near Hartford, Conn., for almost 30 years, along with his wife, the choreographer and dance educator Catherine Fellows Johnson. Their daughter Cajai Fellows Johnson has been acting on Broadway in “Frozen.” Jahonie Johnson, a daughter from a previous relationship, lives in Georgia. Since the Allman Brothers’ final show, Jaimoe has continued to play with his own group, Jaimoe’s Jasssz Band, and is forming shifting groups tagged as Jaimoe and Friends.

“One thing I’ve learned in life is hindsight ain’t no 20/20,” he says. “People use that to try and change what they did. I just try to be where I am, and whatever I do, stay as true as I can.”

February 12, 2020

Celebrating Eat A Peach on its Anniversary

In honor of the 48th anniversary of the release of Eat A Peach – it came out February 12, 1972 – I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is a very partial, very abridged version of the story, with materials from Chapters 11 – 13. To read the full story of the making of Eat A Peach, pick up a copy of One Way Out now. Signed copies available here.

If you’re anywhere close to New York city, my Friends of the Brothers band, featuring Andy Aledort, Junior Mack and a great crew of players, will be celebrating the legacy of the Allman Brothers tomorrow, February 13 at The Cutting Room. Tickets available here.

If you’re anywhere close to New York city, my Friends of the Brothers band, featuring Andy Aledort, Junior Mack and a great crew of players, will be celebrating the legacy of the Allman Brothers tomorrow, February 13 at The Cutting Room. Tickets available here. *

Beautiful cover… and my favorite album.

Beautiful cover… and my favorite album.In October, 1971, the Allman Brothers Band completed three songs for their third studio album working with Tom Dowd at Miami’s Criteria Studios: Dickey Betts’ sweet, lilting “Blue Sky,” Gregg’s “Stand Back,” the only song in the band’s catalog to feature Jaimoe alone on drums, and “Little Martha,” a lovely duet with Betts and Duane – and the only song which Duane was ever credited with writing.

The band took a break and returned to the road for a short run of shows, ending on October 17 at the Painter’s Mill Music Fair in Owings Mill, Maryland. They sold 2219 out of 2500 available tickets and made $12,647.

With almost everyone in the band and crew struggling with heroin addictions, four of them flew to Buffalo and checked into the Linwood-Bryant Hospital for a week of rehab: Duane, Oakley, Payne and Red Dog. A receipt shows the band’s general bank account purchased five roundtrip tickets on Eastern Airlines from Macon to Buffalo for $369. Gregg was supposed to go as well and a receipt from the hospital shows that he was one of the people for whom a deposit was paid. He apparently changed his mind at the last minute.

Leaving Buffalo, Duane spent one day in New York, then joined the rest of the band in Macon, returning the evening of October 28. The next day was the birthday of Linda Oakley, Berry’s wife, and a party was planned at the Big House. Duane visited for a while, then got on his Harley Davidson Sportster, which had been modified with extended forks that made it harder to handle. He had also cut the helmet strap so the protective headgear could not be secured. Dixie Meadows and Candace Oakley trailed him in a car.

Coming up over a hill and dropping down, Allman saw a flatbed lumber truck blocking his way. Duane pushed his bike to the left to swerve around the truck, but realized he was not going to make it and dropped his bike to avoid a collision. He hit the ground hard, the bike landing atop him. Duane was alive and initially seemed okay, but he fell unconscious in the ambulance and had catastrophic head and chest injuries. He died in surgery three hours after the accident. The cause of death was listed as “severe injury of abdomen and head.” He was 24 and had been playing slide guitar for less than four years.

Stunned and grieving, the band took a short hiatus before regrouping, gravitating back towards each other and immersion in their work. They committed to fulfilling previously scheduled dates in New York. Their first appearance without their leader was at CW Post College in Long Island on November 22, 1971; it was exactly three weeks after Duane’s funeral

BUTCH TRUCKS: We thought about quitting because how could we go on without Duane? But then we realized: how could we stop? We all had this thing in us and Duane put it there. He was the teacher and he gave something to us — his disciples — that we had to play out. We talked about taking six months off but we had to get back together after a few weeks because it was too lonely and depressing. We were all just devastated and the only way to deal with it was to lay.

WILLIE PERKINS: There were intensely mixed feelings at these shows. It was so painfully obvious that Duane wasn’t there, which created such an empty feeling. You missed him so damn bad, but you also really wanted to prove that it was going to be okay, that there was still a reason to be out there, that the band could do it. There was a tremendous sense of pulling together.

BUNKY ODOM: I can’t imagine what Dickey went through. Here you’ve got Duane in Dickey’s ear all night long and all of a sudden it’s not there any more. How do you fill those shoes? It was just horrible.

JAIMOE: I really can’t remember anything about any of these shows. We just had to play and everyone played and you really didn’t know what you missed more about Duane – being on stage with him or just life in general.

RED DOG: The day after we’d come back from being on tour, living on top of each other for weeks on end, we’d be home and I’d miss Duane and be banging on his door to say hello. Realizing I couldn’t bang on that door hurt, man. It was stunning.

Returning to Miami, the band recorded four more outstanding tracks with Dowd, including “Melissa,” Betts’ instrumental “Les Brers In A Minor” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” Gregg’s defiant response to his brother’s passing.

GREGG ALLMAN: I wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” for my brother right away. It was the only thing I knew how to do right then.

TRUCKS: Of course, the music we recorded was all about Duane. Gregg wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and that was obviously about how to deal with this tragedy, but I think “Les Brers in A Minor” is about Duane just as much. We did everything we could to try and fill the gap and “Les Brers” was Dickey’s response — starting with the title, which is bad French for “less brothers.”

DICKEY BETTS: When I wrote “Les Brers” everyone kept saying they had heard it before, but no one could figure out where, including me. But it’s in my solo on “Whipping Post” from one night. It was just a lick I was playing in there, and years later it showed up in a bootleg, which was kind of amazing. I mean, none of us knew where it came from until that tape surfaced years later. It just sounded familiar.

TRUCKS: We were all putting more into it, trying so hard to make it as good as it would have been with Duane. We knew our driving force, our soul, the guy that set us all on fire, wasn’t there and we had to do something for him. That really gave everybody a lot of motivation. It was incredibly emotional.

BETTS: It was difficult to suddenly have to play slide and I put in some time to get my part down for “Ain’t Wasting Time No More.” I’ve always enjoyed playing acoustic slide and would even often play it with Duane; when the two of us played acoustic blues I was often the one with the slide, but I never cared as much for playing electric slide.

The band also recorded “Melissa,” a song Gregg had written in 1967 — he says it is his first tune he ever considered a keeper after several hundred — but had never recorded.

ALLMAN: When we were finishing Eat a Peach, we needed some more songs and I knew my brother loved “Melissa.” I had never really shown it to the band. I thought it was too soft for the Allman Brothers and was sort of saving it for a solo record I figured I’d eventually do.

The double album Eat A Peach was completed with three live songs: “One Way Out” from the June 27, 1971 final concert at the Fillmore East, and two songs recording during the March At Fillmore East performances: “Trouble No More” – the Muddy Waters track that had been the first song Gregg sang with the band – and the epic, 33-minute “Mountain Jam.” The latter, which took up both sides of a vinyl album, had been an evolving staple of their performances almost since the beginning.

TOM DOWD: When we recorded At Fillmore East, we ended up with almost a whole other album worth of good material, and we used [two] tracks on Eat A Peach. Again, there was no overdubbing.

ALLMAN: We always planned on having “Mountain Jam” on this album. That’s why you hear the first notes of the song as “Whipping Post” ends on At Fillmore East.

TRUCKS: That “Mountain Jam” is only on there because it’s the only version we had on multi-track tape and it was such a signature song of the band with Duane that we simply had to have it on a record. We played it many times so much better, but better a relatively mediocre version than nothing at all.

BETTS: That was probably the worst version of “Mountain Jam” we ever played. When we were recording live, we really were still focused on the crowd rather than the recording.

With recording done, the album had to be mixed. Dowd started the process, but the album had run over and he had other commitments, so Sandlin was called to Miami.

JOHNNY SANDLIN: I think Tom had to work with Crosby Still and Nash. I went down to Miami the last day Tom was still working on it, and sat with him, and he showed me what he was doing and discussed some aspects of recording. As I mixed songs like “Blue Sky,” I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there’s not going to be any more from him.

I was very proud of my work on Eat A Peach but really pissed because I did not receive credit, only a “special thanks.” It was the first platinum record I’d ever worked on and it meant a lot to me, so that felt like a slap.

TRUCKS: After we were all done and the album was being finalized, I walked into Phil’s office and they showed me the beautiful artwork, with this title on it: The Kind We Grow in Dixie. I said, “The artwork is incredible, but that title sucks!”

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

Then I hand-lettered the Allman Brothers name and photographed it with a little Kodak camera and had it developed at the drugstore, then cut the letters out and pasted them on the side of the truck, under the peach. Duane was still alive and the album had not been titled. We figured we’d go back and add that.

TRUCKS: Duane didn’t like to give simple answers so when someone asked him about the revolution, he said, “There ain’t no revolution. It’s all evolution.” Then he paused and said, “Every time I go South, I eat a peach for peace.” That stuck out to me, so I told Phil, “Call this thing Eat a Peach for Peace,” which they shortened to Eat A Peach.

It didn’t occur to me until decades later that Duane’s comment was a reference to T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” though I knew Duane was a big fan. I was reading Prufrock and came across the reference to eating a peach and was blown away. The symbolism is obvious. Prufrock was totally anal and didn’t want to do anything that would get messy and there’s nothing messier than eating a peach. Duane would have loved that metaphor.

POWELL: The cover was kind of a new approach, a soft sell, because it did not say the name of the album – and the name of the band was just in tiny letters. We left that to a sticker on the shrink-wrap. When we showed it to someone at the label, he said, “They are so hot right now, they could sell it in a brown paper bag.”

The double album opened up as a gatefold filled with another Wonder Graphics piece of art; an entire universe that seemed to promise some kind of psychedelic paradise. It told a story of happy, mystical brotherhood that was receding ever further into fantasy as the band grappled with the tragedy of Duane’s death.

Looking forward to this show!

Looking forward to this show! POWELL: That was really a cooperative venture between Jim and I, completed with almost no planning or discussion. We were working on a large piece of illustration board, on a one-to-one scale – it was the size of the actual spread – and we just started drawing, with Jim’s work primarily on the left and mine on the right. This work was profoundly influenced by [Hieronymous] Bosch.

The whole thing was done over the course of one day while we were in Vero Beach, Florida. While one of us was drawing or painting, the other was out swimming in the ocean. We swapped off this way with virtually no conversation about the drawing, just fluid tradeoffs.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

January 24, 2020

Butch Trucks Gone 3 Years Ago today.

Wow. It’s been three years since we lost Butch Trucks.

Below is a verbatim repost of what I wrote the next day in a haze of sadness, confusion, anger and exhaustion. There are some edits I would normally make, but I think it best to let the rawness stand. I was operating on no sleep because I had gotten a call confirming the awful news at midnight and spent all night staring at the ceiling in disbelief, tossing and turning in anguish, anger and self recrimination.

It was a shocking day and it remains shocking now if I pause to give it any depth of thought. I think of Butch sometimes in the middle of driving or walking and gasp at the realization of what happened. I still can’t fully accept it and I don’t think I ever will. The feeling has only been intensified this year by Neal Casal’s suicide. Another musician whose friendship I really valued and whose death left me reeling, and pondering about the despair I didn’t know about or understand.

As with all suicides of someone you knew and cared about, both of these deaths left me questioning my own actions or lack thereof. Could I have done anything? Should I have been aware of the depth of his sadness? Would any of it have mattered? I do feel certain that Butch had no idea about the breadth and depth of love and caring for him, a heartbreaking realization every time it enters my mind.

A month later, I organized a grand tribute to Butch at the since-closed American Beauty with help from my friends at Live for Live Music. Here’s my report on that event, which led directly to the formation of Friends of the Brothers. Each and every show we play is in part a tribute to Butch and Gregg, who died just five months later.

Rest in Peace Butchy. You are missed more deeply by more people than you ever could have known.

If you’re struggling, please know that you’re not alone. Confidential help is available for free. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Butch had the fire until the end.

Butch had the fire until the end.Claude Hudson “Butch” Trucks (b. May 11, 1947, d. January 24, 2017)

It’s with a very heavy heart that I report the death of Butch Trucks, drummer, founding member and bedrock of the Allman Brothers Band. I am stunned to be writing these words, having communicated with Butch several times in just the past few days. My fingers are frozen just looking at the top of this page and seeing the words pouring onto my screen

Butch was devastated and angry about Trump’s election and had vowed to live at his house in the South of France throughout the new president’s term, but I doubted his resolve because he loved his grandchildren too much; I watched him light up with joy holding his new grandson at last summer’s Peach Festival. He was also very excited about playing with two bands: his Freight Train Band and The Brothers, recently renamed from Les Brers, featuring his Allman Brothers backline mates Jaimoe and Marc Quinones, as well as former ABB members Jack Pearson and Oteil Burbridge, plus Pat Bergeson, Bruce Katz and Lamar Williams Jr.

Tulane homecoming 1970 – Sidney Smith

Tulane homecoming 1970 – Sidney SmithTo the end, Butch remained an incredibly powerful and melodic drummer whose parts defined the Allman Brothers’ classic songs as much as any guitar riff, bassline or vocal. I was on the road with Les Brers last fall and they put on excellent shows. I can barely find the words to describe my own joy at standing alongside Butch, Jaimoe and Marc again; it was like coming home to something very special and indescribable. It was a physical sensation as much as anything; something I felt deep in my bones and which gave me a feeling that I couldn’t have known I missed so much until I felt it again. I wish every one of you could have watched an Allman Brothers show from the side of this percussion powerhouse. It was an overwhelming experience and one that helped you understand the very deep, profound impact the drummers had on the greatness of the music.

Butch and Duane, Piedmont Park Atlanta, 1969.

Butch and Duane, Piedmont Park Atlanta, 1969.Butch was irascible. He could be grumpy. He was also very bright, well versed in all manners of things. And he delighted in talking about it all. In March 2015 we spent a lot of time together over one weekend when he was doing some events in New Jersey and I drove him around while we talked in depth about anything and everything. I heard some wild Allman Brothers stories for the first time; maybe he figured they were safe to let out now that the book was done!

Bothers forever. Photo by Derek Trucks during final Allman Brothers band rehearsals, October 2014.

Bothers forever. Photo by Derek Trucks during final Allman Brothers band rehearsals, October 2014.He came to my house for breakfast with my family in great spirits and was extremely kind and gracious to my wife and children. He also engaged my Uncle Ben, Dartmouth grad and retired judge, in an in-depth conversation about their shared passions for philosophy and physics. He was impressed that my then 17-year-old son Jacob knew his philosophers and that made me very proud. Later that afternoon, we did a talk together at Words, Maplewood’s bookstore and owner Jonah Zimiles was wowed. He later told me that Butch was his favorite guest ever – and the store has hosted a cavalcade of literary stars.

My relationship with Butch first deepened over a book – and it wasn’t One Way Out. He reached out to me in 2011 after reading about my memoir Big in China in Hittin the Note magazine. He was fascinated by my story about playing music in China and our relationship deepened. Throughout the writing of One Way Out, Butch answered my phone calls and emails consistently and quickly and was always ready to share an opinion or memory. He was, in short, an invaluable resource – and he immediately agreed to write a Foreword when I asked. Then he almost as quickly wrote it by himself, straight through, and it ran with very little editing. That’s not how celebrity Forewords and Afterwords usually happen.

Paul family breakfast with Uncle Butchie.

Paul family breakfast with Uncle Butchie.Butch played with Duane and Gregg long before the Allman Brothers Band formed in March 1969. The brothers briefly hooked up with Butch’s folk rock band The 31st of February and recorded an albumin Miami that Vanguard Records rejected. It included the first properly recorded version of “Melissa” as well as “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg’s moving tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. Musical history may have been written differently if Gregg had not flown back to Los Angeles and learned that he was still contractually bound to Liberty Records. Duane moved on to Muscle Shoals and began establishing himself as a session musician.

Eventually, Duane would appear at Butch’s Jacksonville home. He wrote in his Foreword to One Way Out:

“…there came a knock on my door and there was Duane with an incredible-looking black man. Duane, in his usual way, introduced us to each other as Jaimoe, his new drummer, and Butch, his old drummer…. He left Jaimoe at my house and, for the first time in my middle class white life I had to get to know and deal with a black man. It changed me profoundly. Over forty four years later, Jaimoe and I still best of friends and I am very proud to call him my brother.”

Three drummers – by Kirk West

Three drummers – by Kirk WestOver the last four years, Butch established a wonderful, warm family vibe at his Roots, Rock Revival Camp near Woodstock. It was his baby, and Oteil as well as Luther and Cody Dickinson were the other core counselors Bruce Katz, Bill Evans, Roosevelt Collier and others also were involved. I attended the first two and they were fantastic. It’s hard to over-state what he created up there: a small but growing and fiercely loyal band of brothers and sisters.

Trucks is the third founding member of the Allman Brothers Band to leave this mortal coil and the first since Berry Oakley in 1972. Founder and guiding light Duane Allman died in 1971, of course. You either understand how I feel right now or you don’t. If you do, I offer a digital hug of brotherhood. I send my deepest condolences to Melinda, Elise, Seth, Vaylor, Chris, Duane, Derek, Melody and all other members of the bountiful and wonderful Trucks family. Condolences go out also to the entire extended Allman Brothers Band family. It’s a sad, sad day in our little world, friends.

Any media members are free to quote at will from the obituary as long as you promise to not say that Derek Trucks was Butch’s son. He is his nephew!

January 20, 2020

Enjoy Gregg Allman’s beautiful remembrance of MLK

Every year on MLK Day I share “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg Allman’s beautiful tribute to Dr. King, which he wrote and recorded in 1968, shortly after the assassination.

Photo – Derek McCabe

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Gregg Allman wrote this song for Dr. King but it was never on any of his proper releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back from Florida to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… There are multiple versions of it, and this is not my favorite but I think it’s a great tribute to a great man and the person who put this video together with pics of Dr. King did it justice, though he misidentifies it as being The Hourglass. This tracks was actually cut with Butch Trucks’ The 31st of February and produced by Alaimo.

As always, I think it’s important to remember that when Dr. King was assassinated he was in Memphis marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so. It bothers me that we have garbage pickup today. Let’s not allow MLK Day to become another excuse for sales.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

January 3, 2020

Allman Brothers to pay tribute to themselves March 10 at MSG

Ah, I can finally spill the beans. This info has been burning a hole in my pocket….

As reported first this morning in Rolling Stone by my friend David Browne… the surviving members of the final version of the Allman Brothers Band will be celebrating their 50th anniversary March 10 at Madison Square Garden.

“I can’t wait to play again with my Brothers.”

–Jaimoe

Jaimoe, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Oteil Burbridge and Marc Quinones will reunite. Drummer Duane Trucks, Derek’s brother and Widespread Panic member , will fill in for his late uncle Butch. Reese Wynans, best known for his work with Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble, will fill the organ chair in a neat bit of unbroken circling; Reese played in The Second coming with Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley, and played in the original jams organized by Duane Allman as the ABB was forming. He moved on when Gregg Allman returned from Los Angeles. Pianist Chuck Leavell will also be on stage “for a few numbers” – presumably including “Jessica.”

The event will pay tribute to the band’s 50th anniversary, albeit a year late. “Hard to believe it’s been five years since our final show at the Beacon,” says Warren Haynes. “We had all talked about doing a final show at Madison Square Garden which never came to fruition. What a great way to honor 50 years of music and fulfill that wish at the same time.”

The 2003 iteration of The Allman Brothers Band—founding members Gregg Allman, Jaimoe and Butch Trucks plus Warren Haynes, Marc Quinones, Oteil Burbridge and Derek Trucks— would prove to be the longest-running line-up and most consistent in its live performances. The group played its last live performance October 28, 2014, at New York’s Beacon Theatre. Of that night— which was the last of over 230 sold-out shows covering 25 years of spring residencies at the Beacon—Rolling Stone’s David Fricke said “it will take more than a peach to get me through next March. It was never spring, I always said, until I saw the Allmans peakin’ at the Beacon. Tonight was a generous, continually thrilling farewell. It will make the leaving that much harder to bear.”

I’m told there will be no additional guests and that Dickey Betts will not be playing. I know a lot of people will be questioning that. I think it’s worth remembering that he hasn’t appeared on stage in quite a while.

Ticket presales begin on January 7, with public on sale on January 10 via Ticketmaster.

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,B00167PNUI,B004FRVE18,B00ILAWJLO";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "5b6903db4c77a9df46a17f529f76f07f";

December 12, 2019

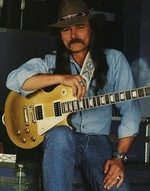

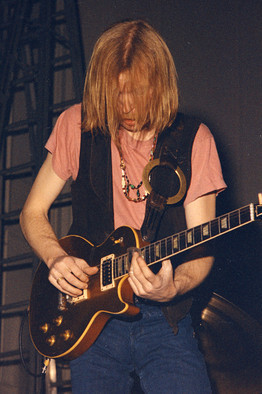

Happy Birthday Dickey Betts. A blast from the archives – Dickey and his Gibsons

Today, December 12, 2019, is Dickey Betts’ 76th birthday. Happy birthday to an incredibly diverse, unique guitarist, singer and songwriter, whose distinct, melodic guitar licks formed the backbone of what we all know as the Allman Brothers’ signature sound. To mark it, let’s look back at this story I did for Guitar World in 2001 when Gibson released his signature model Les Pauls. Duane Betts plays one of the goldtop prototypes – maybe one of the ones we saw and played that night.

In 2001, I went out to Long Island to introduce Dickey Betts to Andy Aledort, who would be working with him on a column for Guitar World. Dickey only wanted to do interviews with me, but I assured him that if he met Andy he would love him. That was the beginning of a beautiful friendship; Andy has now been playing with Dickey for about 8 years.

After we did the interview at Dickey’s hotel room, we hung out all night and eventually outside the Westbury Music Fair, where he would be performing, Dickey showed us the prototypes of his upcoming Gibson signature guitars. Here’s the story I wrote.

Dickey showing off the prototypes on his bus, 2001. Rare time when a photo captures the interview. Photo by Andy Aledort.

Dickey showing off the prototypes on his bus, 2001. Rare time when a photo captures the interview. Photo by Andy Aledort.“Look at this thing, man! It’s beautiful!” Dickey Betts stands in the back bedroom of his tour bus and thrusts forward a gorgeous Gold top. If you didn’t know better, you’d swear it was Goldie, his famous ’57 Les Paul which he played in the Allman Brothers Band for over 20 years. Except that Goldie is, in fact, sitting just a few feet away and is actually no longer gold. (More on that in a moment.)

“This is a ’57 reissue from the Gibson Custom Shop, a prototype of my signature guitar, and it’s a great instrument,” Betts says. “People don’t have to spend 25 or 30 grand to get a vintage guitar any more. This is just as good and I’m very proud that it is going to have my name on it.”

The Dickey Betts Signature Series will eventually feature two models. The first one, an “aged” ’57 reissue Gold top based on the instrument Betts proudly showed off, was introduced in July. Each of them is made in the Gibson Custom Shop then hand-finished by Tom Murphy, a luthier famous for his uncanny ability to match a vintage finish. Vintage lovers will be overwhelmed by the guitars’ uncanny resemblance to a decades-old instrument, but for Betts esthetics are a distant second to playability.

Dickey and Goldie. Photo – Kirk West

Dickey and Goldie. Photo – Kirk West“What I care about is how a guitar sounds and feels and as soon as I picked a few notes unplugged on this, I knew it was a great one,” Betts says. “It’s got great wood and a great finish, which lets the sound ring rather than stifling it. I think I might actually like it more than Goldie now.”

Oddly, Goldie is now a beautiful redtop since Betts himself stripped it and refinished it several years ago. “It had been really worn down by all the use and I just decided to make it how I wanted it,” Betts explains. “Some people think it’s nuts to do something like this to such a valuable guitar, but it’s a working tool for me.”

Betts also recurved the pickguard by hand to better suit his needs, then lowered its profile. He dressed up the hardware by adding a sterling silver Indian belt buckle to the input jack and a silver ring to the toggle switch cover. All of this will be recaptured on the second line of Dickey Betts signature guitars.

“We are going to take Goldie to the shop and put the micrometers on it,” says Rick Gembar, general manager of Gibson’s Custom Shop. “The Dickey Betts redtop will feature all the little things particular to his instrument. These are some of the ultimate guitars on the planet.”

October 29, 2019

Duane Allman’s Spirit Was Alive And Well in 2014

I wrote this article for the Wall Street Journal. It ran on 10-28-14, the day of the last show. I hard forgotten about it a bit and wanted to share again.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Duane Allman plays his famous “goldtop” Gibson Les Paul guitar at Mercer College in Macon, Ga., in 1969. W. ROBERT JOHNSON

Duane Allman plays his famous “goldtop” Gibson Les Paul guitar at Mercer College in Macon, Ga., in 1969. W. ROBERT JOHNSONWhen the Allman Brothers Band take the stage for what they say will be their final show ever tonight at the Beacon Theatre, their current lineup will have been together for almost 15 years, the longest iteration in the group’s 45-year career. But someone who has been gone for over four decades will also play an oversize role: Duane Allman, the band’s founder and visionary leader, who died in a motorcycle crash on Oct. 29, 1971.

Duane was just 24 years old and the Allman Brothers Band had been together less than three years and was just on the verge of commercial success. The guitarist was every bit as much a victim of his times and lifestyle as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison. Unlike them, however, Duane’s musical legacy was not cast in amber upon his death. Instead it has continued to thrive, develop and adapt over the ensuing 43 years.

“I think Duane’s presence is part of the moment by moment journey that this band is still on, both musically and from a vision standpoint,” says Warren Haynes, Allman Brothers guitarist and de facto bandleader for most of the last 25 years. “A lot of times, if there’s a musical question the answer somehow relates to what Duane’s approach would be. Musically, he’s very much with us, and always has been.”

Duane’s continued relevance – his ongoing musical dialogue – is in large part because he very consciously set out to create something that was bigger than himself. It is a testament to the power of group collaboration and to the brilliance of his initial, expansive vision: two lead guitars, bass, two drums and baby brother Gregg on organ and vocals.

“They wanted him to form the Duane Allman Band, but he had something different – something bigger – in mind,” says drummer Jaimoe, a veteran of Otis Redding, Percy Sledge and other r&b acts who was the first musician Duane asked to join his new band.

Great lead guitarists, like fighter pilots, surgeons and All Pro quarterbacks, have huge egos and rarely look to share the spotlight. Duane Allman took the highly unusual step of setting out to find another great lead guitarist to help spark him and his burgeoning band. He found that player in Dickey Betts, a fellow Floridian who already had a huge local reputation. Betts had an utterly distinct sense of melody that played a huge part in shaping the Allman Brothers Band’s distinct sound and was a perfect launching pad for Duane’s guitar explorations.

The Allman Brothers Band from left, Duane Allman, Berry Oakley, Greg Allman, Butch Trucks, Jaimoe and Dickey Betts in 1970. EVERETT COLLECTION

The Allman Brothers Band from left, Duane Allman, Berry Oakley, Greg Allman, Butch Trucks, Jaimoe and Dickey Betts in 1970. EVERETT COLLECTIONTogether, Betts and Allman redefined the possibilities of how two rock guitarists could work together. The pair alternated taking leads while also supporting each other with harmonies and counterpoint rather than one player sticking largely with rhythm patterns. The pair created a template that busted open the possibilities of the instrument, and which the band still follows today, with Duane long deceased and Betts out of the band since an acrimonious 2000 split.

By insisting that he not be the focal point of his new band, Allman paradoxically created a model that ensured his legacy, influence and musical vision would live forever.

“It’s almost like he’s with us,” Gregg Allman said of his late brother in my book One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. “Sometimes when I’m on stage I can feel his presence so strong… it’s like he’s right there next to me.”

During these Beacon shows, Duane Allman’s presence onstage has been more than spiritual or metaphorical. Three of the late guitarist’s Gibson Les Pauls have been present and played by Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes. One, a 1957 goldtop that is usually on display in Macon, Ga., at the Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House, has been a regular visitor to the stage in recent years. The other instruments have made guest appearances, and their presence seemed to alter the third show on Friday, Oct. 24, with everyone suddenly giving it a little extra power and passion.

On the eve of the final six shows, Allman stood in the lobby of the Beacon and reflected again on the role of his late brother. “He gave me hell and drove me crazy quite often,” he said. “But he lit a fire under me and under all of us.”

It’s a fire that’s still burning. The Beacon shows have been ending at about 11:30 p.m. If they play until midnight tonight, they will end their run on the 43rd anniversary of Duane’s passing, which would be an entirely appropriate coda.

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "56469b4e0554f0c0218b89afb6f96c83";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B00YEEUEOU,B001SERYPG";

The final bow – Photo – Derek McCabe

The final bow – Photo – Derek McCabe

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

The Allman Brothers Band’s final show – 5 years ago last night!

Five years ago today, the Allman Brothers Band played their final show at the Beacon Theatre. You can order a CD of the final show right here. FIVE F’IN YEARS??

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

I covered the final shows every which way, posting on Facebook, covering immediately for Billboard, with a story I had to get up and write with about two hours sleep, and writing the following story for Guitar World, with a little bit of time to digest and talk to Jaimoe, Warren and Derek.

The paperback edition of One Way Out includes a full chapter on the tumultuous final year. It includes some of this material, and so much more. Click to order. If you want a signed copy, just drop me a line. Enjoy the story. It’s still emotional for me to read this!

The final bow – Kirk West

The final bow – Kirk WestThe Allman Brothers Band closed out their 45-year Hall of Fame career with six shows at New York’s Beacon Theater, October 21-28. The group’s final year was dogged by controversy. Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes announced in January they would no longer tour with the group after this year, but also said it had been a band decision, Gregg Allman and drummer Butch Trucks sent mixed signals about whether the band was really retiring. The group had to postpone four March shows at the Beacon when Gregg was physically unable to perform, and the singer also had to cancel a host of solo dates.

Yet things seemed calm as they entered the run of final shows. On the eve of the run’s first show, just before a final rehearsal on the Beacon stage, Gregg Allman stood in the theater’s lobby and seemed quite at peace with the band’s decision.

“It’s been 45 years,” he said. “I think that’s about enough.”

He also said that the group had decided not to have any of the guests who have become a Beacon staple: “There’s only six shows left and we’re going to go out with just the seven band members.”

On opening night, the theater was filled with an air of anticipation and reverence, a step beyond the normal excitement that has always met the band at the Beacon, where they have sold out 238 shows since 1989. They closed the first set with “You Don’t Love Me.” Before applause could swell, Haynes played a plaintive, almost mournful lick, which revealed itself as the melody of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Derek Trucks responded with a sacred slide wail, Gregg’s churchy organ fell in with them, and the whole band swooped in for a breathtaking instrumental version of the traditional American song of mourning, which always played a special role in the Allman Brothers and which the group played at Duane Allman’s funeral.

The next night, the guitarists again started an instrumental “Circle,” this time offering up a more jagged, aggressive reading in the jammed out coda of “Black Hearted Woman.”

Derek McCabe photo

Derek McCabe photoBefore the third show, on Friday October 24, Duane’s two Gibson Les Pauls, a cherrytop and darkburst, arrived from the Rock and Roll of Fame. (See this story for full details.) They joined the 1957 Les Paul which Derek had been intermittently playing since the first show, marking the first time Duane’s three primary guitars were all together, and their presence seemed to animate the band, who played their best show since the 40th anniversary performance of March 26, 2009. The surge of energy was testament to the remarkable power Duane exerted on the Allman Brothers Band until the very end. Trucks and Haynes’ playing took on more urgency. The two moved closer together, leaning in to better hear and respond to each note. The drummers hit with more force. Gregg Allman was fully, absolutely present, and singing with extra power and precise phrasing.

“Those guitars were inspiring to play,” says Haynes. “They are not in the greatest shape after not being played for so long, but the sound is unreal. The tone they generate is so remarkable and distinctive; it is the sound of Duane.”

During Friday’s show-ending “Whipping Post” encore, the band stopped on a dime and went into “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” again, but this time Gregg sang it, a mournful, haunting lament that led right back into the finale of “Whipping Post.” The band was flying at a very high altitude.

The Allman Brothers mostly maintained this level for two more nights, with instrumental versions of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” inserted into “Jessica” and “Les Brers in A Minor,” respectively. That left one final show, on Tuesday, October 28th. Grandiose rumors circulated: They would play four sets. They would play until sunrise, just like at the Fillmore East. They would play an hour-long “Mountain Jam.” All the hyperbole turned out to be just a slight exaggeration.

From the first notes, it was clear this was going to be a special night. The reverential, ecstatic crowd was hanging on every note, each of which was played with intent and focus. It suddenly seemed likely that the band could actually pull off Derek Trucks’ desire to go out on top of their game.

The band kicked off with a brief reading of the instrumental “Little Martha,” transitioning into a “Mountain Jam” that was little more than a tease, then launching into the first songs from their first album, “Don’t Want You No More” and “Not My Cross to Bear.”

Butch Trucks summoned the old freight train power that drove the band to their greatest heights. Jaimoe complemented his partner’s fury with swinging accents and added power. Percussionist Marc Quinones heaped coal into the furnace. Gregg Allman sang as well as he has in years, while his organ seasoned every song. The frontline of Haynes, Trucks and Oteil Burbridge pushed one another higher in an endless conversation of push-pull rhythms and interwoven parts.

“I had a good feeling from the very first night,” says Derek Trucks. “But It wasn’t really until the show started on the last night that everything seemed to fall into place and we all knew this had the potential to really become something special.”

The show largely leaned on Duane-era material, plus three songs recorded after Duane’s death but closely associated with him: “Melissa,” and “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” which were both played at his funeral, and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” which Gregg wrote in response to his brother’s death. A Haynes-sung “Blue Sky” paid unspoken tribute to founding guitarist Dickey Betts, who has not performed with the band since 2000. The only late-era song in the playlist, interestingly, was “The High Cost of Low Living.”

Derek, Duane’s goldtop. Photo- Derek McCabe

Derek, Duane’s goldtop. Photo- Derek McCabeWhen the show ticked past midnight, the Allman Brothers were wrapping up their career on October 29, the 43rd anniversary of Duane’s death. They played an extended version of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” wrapped in the middle of a massive “Mountain Jam.”

After an encore of a high energy “Whipping Post” the band walked to center stage as the Beacon shook with applause. It was startling to see the seven members together, arm in arm, waving and bowing, because the Allman Brothers have never been a group bow type of band. Gregg has gone whole Beacon runs without saying much more than “Thank y’all,” but he took the mic and offered some eloquent words of thanks and reflection. Then he said that they would close out with the first song they ever played together. Every hardcore in the audience and there weren’t many people there who didn’t meet that description- knew what was coming next: the band’s reinterpretation of Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More.”

The whole audience sang along, leaning forward so much that it felt like the theater might tip over backwards. When the song ended, no one on stage seemed to know what to do, lingering by their instruments. Butch and Jaimoe thrust their arms in the air in triumph. Gregg stood and waved. Haynes and Burbridge embraced. Quinones walked to the front and handed drumsticks to the crowd.

The crowd remained in their seats as a slide show of the band’s history, heavy on Duane and Berry Oakley, rolled on screen to the recorded strains of the lilting instrumental “Little Martha.” It was Duane’s only composition, the notes of which decorate his gravestone. It was also the tune that began this night four and a half hours earlier. The circle was complete, unbroken.

“I think the one thing everyone who was in that room could agree on is the night happened exactly as it should have,” says Derek Trucks. “There was something really honest and pure and it was a bonafied moment, which don’t happen too often on Planet Earth.”

Jaimoe played the shows the highest Allman Brothers compliment, saying the spirit, energy, musicianship and tireless flow reminded him of the original band, that elusive gold standard every other iteration has been chasing like a ghost since 1971.

“Those dates were a lot like the original six,” he said. “We could have kept playing more nights.”

amzn_assoc_placement = "adunit0";

amzn_assoc_search_bar = "true";

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = "alanpaulinchi-20";

amzn_assoc_ad_mode = "manual";

amzn_assoc_ad_type = "smart";

amzn_assoc_marketplace = "amazon";

amzn_assoc_region = "US";

amzn_assoc_title = "My Amazon Picks";

amzn_assoc_linkid = "56469b4e0554f0c0218b89afb6f96c83";

amzn_assoc_asins = "1250040507,1250142830,B00YEEUEOU,B001SERYPG";

The final bow – Photo – Derek McCabe

The final bow – Photo – Derek McCabe

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});