Alan Paul's Blog, page 34

June 11, 2014

Expanded Fillmore East concerts to be released

So the full Fillmore concerts, long rumored, are finally on their way. A new 6-CD set, The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings, will be released on July 29. It includes at least 14 previously unreleased songs. This is the one we’ve been waiting for and I’m anxious to get my hands upon one.

The collection is available through Hittin the Note by clicking here. It is the reccomended source for all Allmans products.

PRESS RELEASE… TRACK LISTINGS AT THE BOTTOM

One of the best live albums of all time is about to get considerably better. The Allman Brothers Band’s cornerstone LP, At Fillmore East, compiled from the four sets recorded on the weekend of March 12-13, 1971, has been expanded, stretching over six CDs with fifteen unreleased tracks. Additionally, The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings contains the complete June 27 performance during the iconic venue’s final weekend, after the band was handpicked by impresario Bill Graham to headline closing night. Produced by Bill Levenson, who compiled the definitive Skydog: The Duane Allman Retrospective (Rounder, 2013), The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings captures the most inspired improvisational rock unit ever at the peak of their prodigious powers, blazing their way through extended instrumental elaborations, so taut and virtuosic, that the crowds that packed the Fillmore East on those memorable nights were utterly transfixed. When it came to live performance, no other band could touch the Allmans.

In his scrupulously detailed notes for the set, Allmanologist John Lynskey writes: “From its inception in March 1969, the Allman Brothers Band rapidly established a near-mythical reputation through its incendiary, marathon concerts. No other group could touch the Allman Brothers when it came to extended, improvised jamming; they truly were in a league and dimension of their own. Duane Allman was joined by his brother Gregg on keyboards and vocals, the dual drumming combo of Jaimoe and Butch Trucks, bassist extraordinaire Berry Oakley, and Dickey Betts, Duane’s foil on guitar. Together, these individually talented artists blended into a unit whose sum exceeded the total of its impressive singular parts. The group toured relentlessly-they spent 300 days on the road in 1970 – honing their sound and building a loyal fan base, one show at a time. An Allman Brothers’ concert could not be explained, it could only be experienced, and by word of mouth, the group became known as ‘the people’s band’ for their no-frills approach to live music.”

In his scrupulously detailed notes for the set, Allmanologist John Lynskey writes: “From its inception in March 1969, the Allman Brothers Band rapidly established a near-mythical reputation through its incendiary, marathon concerts. No other group could touch the Allman Brothers when it came to extended, improvised jamming; they truly were in a league and dimension of their own. Duane Allman was joined by his brother Gregg on keyboards and vocals, the dual drumming combo of Jaimoe and Butch Trucks, bassist extraordinaire Berry Oakley, and Dickey Betts, Duane’s foil on guitar. Together, these individually talented artists blended into a unit whose sum exceeded the total of its impressive singular parts. The group toured relentlessly-they spent 300 days on the road in 1970 – honing their sound and building a loyal fan base, one show at a time. An Allman Brothers’ concert could not be explained, it could only be experienced, and by word of mouth, the group became known as ‘the people’s band’ for their no-frills approach to live music.”

As Lynskey notes, the Allman Brothers Band’s magic has always existed primarily on the concert stage, but on the weekend of March 12-13, 1971, when they rolled into Manhattan to play four shows at the iconic East Village venue, they raised the bar higher than ever. “That weekend in March of ’71 when we recorded At Fillmore East, most of the time it clicked,” drummer Butch Trucks recalls. “We were finally starting to catch up with what we were listening to. We had lived together…we got in trouble together; we all just moved as a unit. And then, when we got onstage to play, that’s what it was all about-and it just happened to all come together that weekend.”

The four shows were recorded by veteran Atlantic Records engineer/producer Tom Dowd, who’d not only produced the Allmans’ second album, Idlewild South, but also the sessions for Derek & the Dominos project, putting Duane Allman together with Eric Clapton for some mind-blowing extended guitar duels. That album, Layla, dramatically backed up those who’d been calling the upstart Allman Brothers Band the most exciting live act on the planet, and its little-known 24-year-old leader a fiery six-string virtuoso to rival Clapton, Beck and Page. Dowd and Atlantic, consequently, wanted to put out a live album to capture a skilled and adventurous band in full flight, the two guitars circling each other like a pair of falcons, stretching their material into thrilling and electrifying shapes. No matter that the Allmans had yet to tackle most of their live material in the studio-this band wasn’t about the studio.

“If we could just get people to come out and see us,” Duane Allman told interviewer Bud Scoppa on the afternoon of Friday, March 12, before their first pair of headlining sets, “I know they’d like what they heard.”

How right he was.

The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings

CD 1

March 12, 1971 – First Show

1. Statesboro Blues 4.08 (previously unreleased)

2. Trouble No More 3.48 (previously unreleased)

3. Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’ 3.19 (previously unreleased)

4. Done Somebody Wrong 4.01 (previously unreleased)

5. In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed 17.05 (previously unreleased)

6. You Don’t Love Me 16.55 (previously unreleased)

CD 2

March 12, 1971 – Second Show

1. Statesboro Blues 4.12 (previously unreleased)

2. Trouble No More 3.50

3. Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’ 3.28 (previously unreleased)

4. Done Somebody Wrong 4:30

5. In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed 19.50 (previously unreleased)

6. You Don’t Love Me 19.10

7. Whipping Post 20.00 (previously unreleased)

8. Hot ‘Lanta 5.09

CD 3

March 13, 1971 – First Show

1. Statesboro Blues 4.20

2. Trouble No More 3.48

3. Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’ 3.47

4. Done Somebody Wrong 3.55 (previously unreleased)

5. In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed 13.00

6. You Don’t Love Me 19.10

7. Whipping Post 17.15 (previously unreleased)

CD 4

March 13, 1971 – Second Show – Part 1

1. Statesboro Blues 4.19 (previously unreleased)

2. One Way Out 4.30 (previously unreleased)

3. Stormy Monday 10.14

4. Hot ‘Lanta 5.00

5. Whipping Post 22.00

CD 5

March 13, 1971 – Second Show – Part 2

1. Mountain Jam 33.00

2. Drunken Hearted Boy (with Elvin Bishop) 7.30

CD 6

June 27, 1971 – FILLMORE EAST Closing Show

Introduction by Bill Graham (previously unreleased)

1. Statesboro Blues 5.52

2. Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’ 3.34

3. Done Somebody Wrong 3.37

4. One Way Out 5.01

5. In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed 12.44

6. Midnight Rider 3.01

7. Hot Lanta 5.41

8. Whipping Post 19.17

9. You Don’t Love Me 17.56

June 10, 2014

An interview with Triangle mastermind Tex Winter

In honor of Derek Fisher’s hiring as the New York Knicks new head coach by Phil Jackson, I present this interview with Tex Winter, the mastermind behind the Triangle Offense, so beautifully executed by Phil Jackson, Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. It was conducted for Slam circa 1998. Some of the questions that have me scratching my head now – like asking about Keith Van Horn – must have made sense then.

In honor of Derek Fisher’s hiring as the New York Knicks new head coach by Phil Jackson, I present this interview with Tex Winter, the mastermind behind the Triangle Offense, so beautifully executed by Phil Jackson, Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. It was conducted for Slam circa 1998. Some of the questions that have me scratching my head now – like asking about Keith Van Horn – must have made sense then.

I forgot that Tex stayed with the Bulls and Tim Floyd when Jackson and everyone else who made the team great moved on. I also forgot just how honest he was. Pretty remarkable.

Winter, who coached Kansas State to the Final Four twice, and became a Bulls assistant when he as about to retire, is alive and well at age 92. He is a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame. Enjoy:

*

Chicago Bulls assistant coach Tex Winter has been on a basketball bench for each of the last 52 years, making him the longest-running active coach in hoops, pro or college. He is the architect of the Bulls’ famed triangle offense.

SLAM: It must be great as the innovator of an offense to see it executed to perfection, which you had the pleasure of doing for the last eight years or so.

WINTER: Yeah, it is, but it sort of spoils you. It proves the adage that it’s not necessarily what the offense is that matters, but how well you execute the fundamental skills, and Michael and Scottie and everyone else did so to perfection. But I had teams at Kansas State that executed every bit as well, but weren’t as gifted of athletes. One of the telltales of the system’s success is we won 55 games without Michael when he retired the first time.

SLAM: You’re 77. Why did you come back to endure so much losing this year?

WINTER: I gave a lot of thought to retiring, but Tim Floyd wanted to keep the basics of the offense in place and asked me to help him teach –and learn – it. I felt like I could really make a contribution, and it’s always nice to feel like you’re needed and wanted. I’m not sure I would have returned if Michael and everyone had, because, frankly, those guys didn’t need me any more.

SLAM: How did the Bulls come to use the triangle offense?

WINTER: Phil Jackson and I worked together in the summer leagues and I introduced it to him then. When he became coach of the Bulls, he was looking for an offense predicated on ball and player movement and team offense. I think the reason that he felt so strongly is he played on the great Knicks teams, which really played together beautifully. The triangle gave Phil something to hang his hat on, and great salesman he was, he convinced Michael to accept it, which wasn’t easy, because he realized that individually he would have to make some sacrifices. But Coach Jackson convinced him that if he was going to win championships he had to be part of a team scheme.

SLAM: There seem to be a lot of “almost triangle” offenses popping up.

WINTER: We see more and more fragmented parts of it popping up all the time, but it’s generally been bastardized. I’m flattered that they think it is the solution in any regard, but coaches don’t seem to be able to teach it. It gets blown into this very complicated thing, but I think it’s very simple. I’m not the most brilliant guy in the world. In fact, I’m rather simple minded, so I don’t think I could concoct anything too complex. It’s just different. Most of our players now learn to play in summer leagues and on playgrounds, without a lot of structure in their games, so they develop one-on-one talents, playing in congestion, and they defy a lot of principles of sound team offense. Consequently, they have a hard time when you ask them to become a finger in a glove, instead of one of five hands.

The whole thing is just predicated on some easy principles, like ball and player movement with a purpose; good offensive rebounding positions; spacing, so teams have a tough time doubling the ball; and penetration — the offense is not sound unless you have an opportunity for penetration. I’ll tell you how simple it is – it’s most widespread use is amongst junior high coaches who have kids just learning to play. They’re perfect for it because they don’t have bad habits yet, and learn to operate out of proper, wide spacing. The offense is also good for women’s teams, which tend to play very fundamentally sound ball. In fact, Tennessee coach Pat Summit, who has won the last three national championships has used a lot of it, and she’s come up here with her whole staff for two or three years. The Connecticut women’s coach [Geno Auriemma] has also visited us.

SLAM: Who do you think are some of the league’s most overrated players?

WINTER: Well, I need to proceed cautiously, particularly this year because they could well prove me wrong. We don’t stand to have a great team, and even a lot of players I consider overrated will have the opportunity to inflict some damage. The main thing is, too many players feel like they’re complete players when they’re not, so rather than acknowledge their limitations and play within their ability, they overreach. That was a great thing about coaching Dennis Rodman; he knows his role –rebounding and defense –and plays it to a tee.

I’ve always considered a lot of the big guys overrated, notably Mutumbo and Mourning — by which I mean, in their own minds they feel they’re a lot better than they are. Mutumbo has great physical talents, no question, but it’s questionable how great a basketball player he is. I am such a purist that I look at how good someone is fundamentally. There’s compensation there –they are strong enough to overpower you despite their deficiencies –but they are overrated as pure basketball players.

SLAM: What about Patrick Ewing, one of the Bulls’ great rivals?

WINTER: He is without a doubt one of the all-time great big men, but I don’t think he’s ever been as effective as he could have been. They utilized him on the post as a scorer more than anything else, and he could have been more effective if they had concentrated on him being more of a feeder and a rebounder. The team has not been as effective as it should be with a dominant center like that, but I don’t know if that’s Patrick’s fault. He’s not the coach.

SLAM: What do you think of Keith Van Horn?

WINTER: Like I was saying before about criticizing guys this year… I think there’s an awful lot of ball players with great skills, but whether or not they’re going to be on winning teams is not going to be answered until you see how they fit in to a team or a program. If they don’t, it may be their fault or it may be their coaches.

SLAM: Stacy King was a guy who everyone thought would be great and never panned out.

WINTER: He was a great disappointment to us. We drafted him high and felt he could play a good role in this offense, at both the 4 and 5. And I still feel he should have. I can’t answer why he wasn’t a little bit more successful. He got a lot of shots blocked, and had some definite problems defensively.

SLAM: Who do you think was the most underrated contributor to the Bulls’ success?

WINTER: all of our role players did a great job of knowing their job and fitting in, but I’d say Steve Kerr and Horace Grant were the two who best understood the offense and functioned beautifully in it. I was really let down when we lost Horace. I think the team with him and Scottie on the wings, Cartwright at center, and Paxson and Michael in the backcourt was the best team we ever had here.

Amazon.com Widgets

June 5, 2014

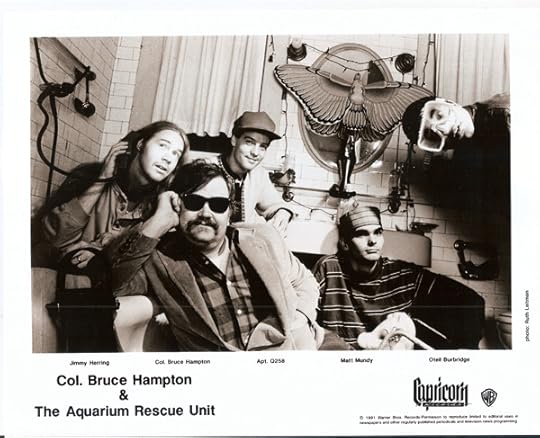

Col. Bruce Hampton and the ARU: An Appreciation

Early ARU photo – note pre-beard Jimmy Herring!

This story originally ran in Relix’ 40th Anniversary Issue.

In February 1992, the reunited Dixie Dregs were coming to New York’s Ritz and I was excited to check them out. Though I had always considered their music sterile if brilliantly constructed, I recognized Steve Morse as a brilliant guitarist. As a young Guitar World Managing Editor, I was anxious to expand my musical scope and appreciation and Steve was someone that I thought I should better understand. Publicist Marc Pucci pushed me to get there early to see the opening act, the oddly named Aquarium Rescue Unit

He assured me that the newly reformed Capricorn Records was very excited about the band, led by a longtime Atlanta cult hero, Col. Bruce Hampton (Ret.). Still pinching myself over living in New York City, working at a major music magazine and having publicists ask me to go to shows, I earnestly arrived at the Ritz close to starting time to check out this band with an open mind but with few expectations. They had just started when I walked in to the half-filed Midtown Manhattan ballroom and strolled right up to the lip of the stage, immediately astounded by what was unfolded.

A skinny redheaded guy with a beard was hunched over a Stratocaster, dispensing lightning fast licks that danced the razor’s edge I love, where everything could fall apart at any moment, though his sure-handed playing and obvious blues rooting made that highly unlikely. To his right, a handsome young man was grinning, eyes cast towards the sky as he worked a six-string bass with the same mix of skill and abandon, sometimes scatting along to the notes he played. On the other side of the stage a dark haired guy with bushy eyebrows was blasting out supercharged bluegrass licks on a Mandocaster – a mandolin in the shape of a mini Telecaster. A brilliant drummer was laying down beats from enough angles to replicate at least two percussionists. Overseeing the whole thing was a crazy little man with a handlebar moustache playing some kind of demented short-scale instrument I would later learn he called a Chazoid. He sang like a bastard child of Bobby Bland and Hazel Dickens and occasionally played wicked, inspired licks. This was obviously the Colonel. He was clearly the ringmaster of this nutty circus, which radiated light and the spark of life and was hilarious without being a joke.

Questions bounced around my racing mind: Who was he? What was this? Why wasn’t everyone talking about this fabulous band? I pushed them all down and out because I wanted to stay in the moment, to drink deeply from this heady brew. I’d like to tell you how the rest of the crowd reacted, but I have no idea. I wasn’t looking around, solely focused on the stage, experiencing something that I have just a handful of times – musical nirvana that hit me in the head, heart and guts at the same time and was all the more powerful for being so completely unexpected.

After the show, I watched the musicians break down their own gear and got guitarist Jimmy Herring’s attention, introducing myself and telling him I’d meet him downstairs. I had been invited to a meet and greet, which I had originally planned on stopping by just long enough to see whether or not they had free beer, but my plans had changed.

The col and I, Eddie’s Attic, 5-15-14. Photo by Rhiannon Bradley.

In a little room downstairs, I chatted a bit with Bruce and spoke at length with Jimmy. We were both somewhat star struck – Jimmy was thrilled that a Guitar World editor had so enjoyed his playing. I was gob smacked that someone like him cared what I thought, and convinced that I had just discovered a major talent. I was right, of course, and as silly as Jimmy’s excitement seemed then and still seems now, it was revealing about both his nature and the group’s circumstances.

“We were making $92 a week and sleeping in one room,” Hampton told me recently. “After two years we got two rooms and we were so ecstatic we had a celebration. There were five of us in a Chevrolet van with 400,000 miles on it. How we did it, I’ll never know, but I never had more fun or made greater music than I did during that run.”

No wonder Jimmy was so happy that I had taken note of this brilliant musical circus; they were playing for love and for each other and I was an outsider acknowledging their instincts were right, that they were onto something. There is no greater satisfaction for an artist than some affirmation that their struggling is not for naught, something they had received precious little of outside their Atlanta base.

This group of five had been playing together for about two years. Bassist Oteil Burbridge and drummer Jeff Sipe (then called Apt. Q258) had been with Bruce for about three more years. Hampton originally hired Oteil as a drummer. “We played about three gigs and then he picked up the bass one day and I said, ‘That’s what you’ll be playing from now on,” Hampton says with a laugh. “He was a good drummer, but he was like the greatest bassist I had ever heard.”

All the musicians came to Hampton as virtuosos. He opened up their boundaries. Hell, he obliterated the very concept of boundaries.

“Old timers would tell me that Oteil was playing too much, but the song was always there,” says Hampton. “He never lost that. And he was 21 and full of this amazing energy, so why not let him be free? Then I told him, whatever he wanted to do, do the opposite.”

But isn’t that a contradictory concept – be free and do the opposite of what you want to do? “Yes!” says Hampton. “That’s it.”

f that contradiction makes perfect sense to you, then you are well on your way to understanding Hampton’s Zambi musical approach, which Burbridge sums up in a few words: “Bruce was our professor of out.”

The Colonel’s educational role was obvious, but to this day he cringes at being called a mentor, even after 20 more years discovering great young players.

“I learn as much from them as they do from me,” he says. “What made me unusual was that everyone my age had either quit or made it. No one was playing clubs and putting together new bands on the cheap like that.”

Hampton had been making music in Atlanta since the late 60s. His Hampton Grease Band drew the attention of Duane Allman, who became a friend and supporter and got the group signed to Capricorn, who sold the contract to Columbia. Hampton says that their 1971 album Music to Eat is the label’s second worst selling album ever. Hampton spent the next 20 years working on his own and with the Late Bronze Age until he started putting together the ARU.

With Oteil at Wanee, 2014.

Hampton says that what he offered his young protégés was guidance. “They were already great when they joined the band, but what I did was try to break their boundaries,” he says. “I’d say, ‘Don’t be a fusion drummer or a blues bass player. Discover who you are.’ It was thrilling to discover all this together, and we went places that no one had ever been before – and very few people saw it.”

While their own shows may have rarely grown beyond large clubs, the ARU played on the early HORDE tours and became prime influences on the many bands and musicians, notably Phish, Widespread Panic and Derek Trucks, who was an honorary member by the time he could have been Bar MItzvahed. The ARU were the jam band Velvet Underground; a group whose influence vastly overwhelmed their commercial success. Most of the members went on to make their marks: Oteil as bassist of the Allman Brothers Band since 1998; Herring with the Allmans, Phil Lesh and the Dead and now Panic; Sipe with a range of bands. Mundy quit the group suddenly in 1993, giving up music. He plays again, though not publicly. Hampton has consistently put together great new bands, including the Fiji Mariners and the Codetalkers. Nothing in his approach to music has really changed.

“You either leave essence or you don’t,” he says. “ You either capture the moment or you don’t and you know at every show if you missed it or hit it, but you don’t know when it’s coming or where it comes from. That elusiveness is what keeps all artists going. But in the ARU, I think we only had one or two bad gigs in four years. Every night it was on and we would push each other to the outer limits. We sometimes played six or eight-hour gigs for 99 cents admission. In other words, we were a mental illness group.”

Anyone who heard this brand of illness either fell in love or scratched his or her head and walked away. But even as the band was earning converts, they were cracking under the strain of the road. Mundy’s departure cost them more than a unique musical voice. “He was the glue,” says Hampton, who quit touring himself within a year. The band continued for a few years with a couple of different singers, before everyone started drifting off to other gigs. They have reunited for brief tours and one-off gigs over the years, most recently at last year’s Christmas Jam in Asheville, North Carolina.

At that first show, I eventually said good bye to Jimmy, who had to load his own gear onto a trailer and push on, and went back upstairs to hear the Dregs. The playing was spectacular, but I couldn’t quite focus on the music. It was exemplary but it existed in the known universe. That no longer seemed like quite enough.

June 4, 2014

Allman Brothers’ low point? “Straight From the Heart” on Solid Gold

Pretty much everyone agrees that the Allman Brothers Band’s low point was their second album for Arista Records, 1980′s Brothers of the Road, and its slight, poppy lead single “Straight From the Heart.” The band had fired the great Jaimoe by then and were trudging along trying hard to recapture a spark during an era that was just not interested.

Pretty much everyone agrees that the Allman Brothers Band’s low point was their second album for Arista Records, 1980′s Brothers of the Road, and its slight, poppy lead single “Straight From the Heart.” The band had fired the great Jaimoe by then and were trudging along trying hard to recapture a spark during an era that was just not interested.

I cover all this in One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band in conversations with Jaimoe, Dickey Betts, Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks, the much-maligned synth/keytar player Mike Lawler, Rook Goldflies and then-manager John Scher among others. Everyone looks back with horror and regret in various mixes.

But a video recently popped up on YouTube of what might be the low point of the low point: the band “performing” “Straight From the Heart” on Solid Gold – everyone lip synched on the show, including the mighty ABB. I’m not sure what is more painful: the halting interview Gregg gives to Marilyn McCoo – “There’s a lot of excitement… good energy” – or the song. Judge for yourself.

Also worth noting that I loved Solid Gold and watched it many, many Saturday nights. But, hey, I was just a music-obsessed kid, taking what I could get.

// ]]>

<A HREF=”http://ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widg... Widgets</A>

June 3, 2014

Warren Haynes’ National Anthem

Warren Haynes performs the National Anthem for the National Museum of American History, where the flag that inspired the song is on display. Enjoy:

May 30, 2014

Allman Bros At the Fillmore East, 1970

In case anyone is still wondering why I spent half of my life writing and reporting One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

Enjoy the Allman Brothers Band at the Fillmore East, 1970.

This clip features four songs from 9-23-70, recorded for PBS. It should be but is not commercially available. Yes, there are some sound glitches and the camera is often on the wrong guy (Dickey’s fingers while Duane is soloing, etc), but nonetheless… this is epic, primal Allman Brothers, featuring the great Thom Doucette on harp as well.

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

May 29, 2014

“One Way Out” with Mike Barnes

Well, you have to give me this much: you get more than blah blah blah at my book talks. What other author sings you his title?

I started out my book talk at Malaprop’s Books in Warren Haynes’ hometown of Asheville, NC by playing and singing “One Way Out” with Haynes’ old friend Mike Barnes.

Check out the sweet Kirk West slideshow running behind us.

May 28, 2014

An Interview With Albert King

Foto by Kirk West

Let’s take another look at this old story, one of the highlights of my years at Guitar World. I wrote the intro a few years ago when the piece ran in Hittin’ the Note.

See many more great rock, blues and country photographs at www.kirkwestphotography.com.

*

Just days after I became the Guitar World Managing Editor in February, 1991, I sat at my desk listening two of my colleagues (“bosses” would have been the word I used at the time) discussing an interview with Albert King, scheduled for the following week in Clevelan

d. They couldn’t think of anyone up to the task of interviewing the great and ornery bluesman. I shifted my weight, cleared my throat and waited for them to ask if I was interested. When the offer didn’t come, I piped up that King was my favorite guitarist and I would be honored to take the assignment. After a bit of back and forth, the job was mine.

As the day grew near, I became increasingly nervous. I desperately wanted to do a great job and he had a reputat

ion as a tough, mean old man. I once saw him fire a sax player on the bandstand – surely he’d cancel an interview without a second thought. I called his manager just before I left for the airport to verify our arrangements. “I told Albert about it,” he said. “Hopefully he’ll remember and feel like doing it.”

I spent the day at my cousin Stephen’s house in Cleveland, preparing for the interview and growing increasingly edgy. It started to snow, first lightly, then heavily, and I drove to the theater through a pelting blizzard. Albert was playing with Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King on a spinning theater in the round, and I fidgeted throughout his set. Following his performance, I arrived backstage at my appointed hour, praying that I would be granted an audience with the King.

I was brought to a small dressing room, crowded with band members and their lady friends. King shook my hand and pointed to a seat next to him. As we began to talk, he turned to the others and shouted, “Be quiet! I’m doing an interview.” Silence fell over the room and all eyes and ears turned to me. I have never felt younger, whiter, shorter, or more insignificant. Albert leaned forward and extended his long arm directly over my shoulder to get at some popcorn. Leaning close, he smiled, flashing two gold front teeth, and told me to commence my questioning.

For 45 minutes, Albert answered my questions, though when he considered something foolish or misguided, he shot me a look that could freeze a volcano. He was patient, professional – and every bit as intimidating as I could have imagined, which somehow made me happy. His personality fit his music to a tee; no one has ever played the guitar with more authority or focused intent.

King, who died of a heart attack at age 69 on December 21, 1992, was a vastly influential guitarist for many reasons: He played with a raw ferocity that appealed equally to fellow bluesman and younger rockers. He was one of the first black electric bluesmen to cross over to white audiences, and one of the first to adapt his playing to Sixties funk and soul backings, on classics like “Born Under a Bad Sign.” But perhaps King’s ultimate legacy is that he embodied two of guitardom’s most sacred tenets: what you don’t play counts as much as what you do, and speed can be learned, but feeling must come from within. The left-handed guitarist played “Lucy,” his upside-down flying V, with absolute conviction and economy. He could slice through a listener’s soul with a single screaming note, and play a gut-wrenching, awe-inspiring 10-minute solo without venturing above the 12th fret.

I last saw King perform about eight months before his death, at Tramp’s, a mid-sized Manhattan club. Arriving after midnight, I imagined his final set would be brief, even perfunctory, and was dismayed when he came onstage and sat down – his towering, 6’-5” hulk was always such a large part of his stage presence. Was he feeling infirm? I was further shaken up when he began noodling leads around the band’s funky vamp in the wrong key. I began to wonder if my hero had lost it, but then he found his footing, caught the groove and began to soar.

King delivered a stirring, two-and-half hour performance, seeming to gain strength as the night wore on, closing the show at 3:00 AM with a coolly passionate version of “The Sky Is Crying” that will remain forever etched in my mind. I left the club with a renewed conviction that music is not about showing off, or impressing fellow musicians, or anything else other than creating sounds that forge a mystical bond with listeners. It’s something that Albert King did with unsurpassed skill.

***

Blues legend has it that Mike Bloomfield, lead guitarist of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and for a time the Sixties guitar hero, once engaged Jimi Hendrix in a cutting contest before thousands of screaming fans. Hendrix drew first and unleashed a soaring, cosmic blues attack. As Bloomfield stood transfixed in awe, struggling to plot a response to Hendrix’s brilliant fury, one thought ran like a mantra through his mindæ“I wish I were Albert King… I wish I were Albert King….”

Two decades have passed, and both Bloomfield and Hendrix are gone. But King and his music remain hale and heartyæeven on a blustery Cleveland night some months ago, when brutal winds and two feet of swirling snow made the city inhospitable to man and blues alike. Inside a suburban club, however, a force of nature even more powerful than a blizzard held sway as Albert Kingæall six-feet-five inches of himæstood puffing a pipe, his upside down Flying V looking like a toy guitar in his massive hands. As clouds of smoke billowed from his snarling mouth, the left-handed King ripped off scorching, jagged blues lines.

On that wintry Ohio night it was easy to understand Bloomfield’s desperate invocation of the massive bluesman in his hour of need. And it was equally clear that King has lost little of the of the devastating blues power that has made his playing the standard of excellence for guitarists from Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton to Stevie Ray Vaughan and Gary Moore.

Several nights after the Cleveland show King, resplendent in an open-collared tuxedo, stepped from a limousine in midtown Manhattan. His pipe was still gripped tightly between his teeth, but the on stage snarl was gone. King was all smiles as he headed into a posh nightclub to receive a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation.

“I never really considered myself r&b,” King said. “I’m a bluesman. But there’s nothing like being honored by your peers. There’s also nothing like this.” His gold teeth sparkled in a broad smile as he held up a check for $15,000, his bounty for a lifetime of groundbreaking work.

While King is inarguably a bluesman, his earliest recordings for Bobbin Records (recently re-released on CD by Modern Blues as Let’s Have a Natural Ball) featured hard-swinging big band arrangements. Later, he would record his most influential workæincluding “Born Under a Bad Sign” and “Crosscut Saw”æfor Stax, backed by Booker T and the MGs, the r&b label’s famed house band.

But whatever the musical setting, King’s lead playing has always been characterized by stinging, river deep tone and a totally identifiable style, developed as a result of his unorthodox technique. The left-handed King plays with his guitar held upside down, treble strings up, which, among other things, causes him to bend his strings down.

“I learned that style myself,” King said. “And no one can duplicate it, though many have tried.”

AP: You’ve recorded a very wide variety of material, much of which has departed from the standard blues formats. How did you arrive at the appropriate approach for any given song?

KING: I did that in the studio. We would come up with different styles to go behind songsæthen I’d do whatever fit. I might try three or four rhythms behind a song, find the one that feels just right and record it. I can hear real good and I never saw the point of limiting what I listened toælots of times I heard new things that surprised me. The guys at Stax [guitarist Steve Cropper, bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, drummer Al Jackson and organist Booker T. Jones, plus the Memphis Horns] were real good for playing with different grooves and helping me find the right one. I liked playing with them because they were good idea peopleæthey’d twist things around into different grooves. It worked real good.

AP: Your guitar style changed noticeably from your early recordings with the Bobbin label to your work with Stax. You didn’t use a much vibrato originally, for instance.

KING: No, I didn’t. I never made a decision to change my style. Some of it I forgot and some of it just automatically changed. Nothing can stay the same forever. I do all of the vibrato with my hand. I don’t use no gadgets or anything. I used to only use Acoustic amps, but I went to a Roland 120 because it’s easier to handle and it puts out for me.

AP: There has always been so much swing to your music. Have you listened to a lot of jazz?

KING: Yes. I’ve always been a lover of jazz — especially big band jazz. On the Bobbin stuff, I used a lot of orchestration and big band arrangements to mix the jazz with the blues. I went for the swinging jazz arrangements and the pure blues guitar.

AP: Your lead guitar has always been very lyrical. Do you think of the guitar as a second voice?

KING: Yes, I do. I play the singing guitar, that’s what I’ve always called it. I also sing along with my notesæit’s how I think about where I’m going.

AP: You don’t play a lot of chords.

KING: No, I play single-note. I can play chords but I don’t like ’emæI don’t have time for them. I’m paying enough people around me to play chords. [Laughs.]

AP: You’re also noted for your tendency to bend two strings at one time.

KING: Yeah. Lots of times I don’t intend to do that but I’m reaching for a bend and bring another one along. My fingers get mixed up, because I don’t practice. When I get through with a concert, I don’t even want to see my guitar for a while.

AP: Have you always felt that way?

KING: No, no. Just lately –in the last four or five years. Since I’ve been really feeling like I want to retire.

AP: You are one the only guitarists I’ve ever heard who will start a song with a bent noteæon “Angel of Mercy,” for instance.

KING: Again, I didn’t plan that out. It’s just what I felt and the way I recorded it. The bent note is my thing, man, and I’ll put one anywhere it feels right. There are no rules.

AP: I’ve heard stories of people who tried to copy your sound but didn’t know that you were playing upside down.

KING: [Laughs] Yeah, I’ve heard that, too. And people who try to restring their guitars to get my sound, and everything else you can imagine. Jimi Hendrix used to take pictures of my fingers to try and see what I was doing. He never quite figured it out, but Jimi was a hell of guitar player, the fastest dude aroundæat the time. There’s some kids who are coming around now…Whew! Forget about it. They burn up the fretboard.

AP: Obviously, Hendrix was a great guitarist. But what do you think of him as a blues player?

KING: Well, to me, he was overplaying to play the blues. He’d hit two or three good licks here and there and then speed them up and hit them over and over until he’d drown out all the good ones. The kids loved it and I liked his playing, tooæthat was his style. But don’t call him a great bluesman. I think he was going more in that direction, but we’ll never know. He didn’t take care of himself.

AP: Your tone is so tough. How do you make it so heavy?

KING: For one thing, I usually keep my treble all the way up, unless I want to play real soft. Then I zip it down.

AP: You really do utilize dynamics effectively. Do you think that’s something a lot of

younger players miss the point of?

KING: Definitely. Because they like to play loud and high all the time. And when you get ready to play chords, you got nothing to go to. I like to mix volumes, treble and bass. There’s a high, there’s a mid-range and there’s a bottom. If you don’t ever mix that stuff up, you’re not a complete player.

AP: What is the single most common mistake young players make with the blues?

KING: Overplaying. They play too loud, scream too high, and run too fast. See, when you overplay, you get too loud and people are gonna mistake what you’re doing for a hole in the air. [Laughs.]

AP: You recently appeared on Gary Moore’s Still Got the Blues album. What did you think of Moore’s guitar work?

KING: Gary’s a good player. To me, Gary and Stevie Ray Vaughan were two of our best young players. I was sure hurt when we lost Stevie. I really wanted to see him and Gary hook up together. I wanted to see that concert. I don’t care where it wasæI would have caught a plane. No doubt about it, both those guys had what it takes to really do it.

AP: Did you give Gary any pointers?

KING: Yeah. I learned a few things from him, he learned a few things from me. I told him to slow it down, double up on his licksæplay every other oneæso that you could feel what he’s doing. If you play too fast or too loud, you cancel yourself out. But Gary plays a whole lot of notes and still sounds good. Every now and then you’re bound to put them in place if you play enough. [Laughs.]

AP: A lot of blues players hit the right note and play the right changes. Yet, something’s missing. What is that something?

KING: I’m going to ask youæYou’re the listener. What do you hear or not hear?

AP: It’s hard to describe. It’s more of a feeling.

KING: That’s it. That’s it, man. Stop right there. Don’t overthink this. I just told you: Once you lose the feeling, you ain’t got nothin’ but a show going. It’s not deep.

AP: So can you learn how to play the blues from a book or reading music?

KING: No way, man. First, you got to get in your mind what you want to play. If you hear a good lic — even if you’re just rehearsing to yoursel — and you feel it, then hit another one and another one and another one. The next thing you know you got 15 or 20 different licks you can hit and they all feel good. But if you rush right through, hitting them all, you’re not even going to know what you did. You’ve got to take your time and learn your bag one lick at a time. And take your time in your delivery.

AP: Your first appearance at the Fillmore [1968] opened up a whole new audience for you. Were you surprised that those people were waiting to hear your music?

KING: Yes, I was very surprise — and very glad. They made me welcome, treated me nice. Bill Graham opened up a young, white crowd for me by putting me in there.

AP: Robert Cray told me that he had one of the biggest thrills of his life when you recorded his song, “Phone Booth.” [“I’m in a Phone Booth, Baby,” Fantasy, 1984]

KING: Yeah, I did one of his songs because the groove fit and that’s what I look for. Robert is a good player and a very nice person, but I haven’t seen him in a while and I hope that success hasn’t gotten to his head. I’ve seen that happen to many, many people, and it’s one of the saddest things you’ll ever see. It matters who you are and what you’re made of. Anytime you think you’re greater than the people that buy your records, that’s when you lose it.

AP: You have such a commanding stage presence. Is there anyone who would intimidate you if they walked on stage?

KING: No. If it’s my show, it’s my stage, and I won’t let anyone mess with me. Believe me.

AP: When did you start using the Flying V?

KING: Oh, man. Way back around 1958. Just about every one I’ve ever had has been custom-made.

AP: Why did you name your guitar “Lucy?”

KING: Lucille Ball. I loved her.

AP: It didn’t have anything to do with B.B.’s Lucille?

KING: You’d have to ask B.B.– mine was named Lucy first.

AP: Have you and B.B. always gotten along, or has there been any tension between youæfor instance over the fact that B.B. is always called “The King of the Blues?”

KING:: Oh God, no. Me and B.B. and Bobby [Bland] always got along great. We go all over the country and sell out every theater we go to. No misunderstandings, no arguments. I’ll open the show for anybody as long as I get paid off. I’ll be asleep in my hotel while B.B.’s still playing and that’s fine with me. B.B.’s a night owl. He closes the show because he stays up most of the night talking, anyhow. [Laughs.]

AP: Has the fact that you once played drums affected your guitar style much?

KING: Not really, except that I can tell immediately if a tempo is off. Being left-handed affected my style more than anything. I started playing drums just because I got a gig with Jimmy Reed and needed the money.

AP: Why haven’t you ever used a pick?

KING: I couldn’t hold one- my fingers were too big. I kept trying and the thing would fly across the house. I just always had a real hard time gripping it, so I learned to play without one.

AP: What type of music did your first band, the In the Groove Boys play?

KING: We only knew three songs and we’d play them fast, medium and slowæthat made nine songs. Somehow that got over all night long.

AP: Did you play strictly by yourself when you started?

KING:I rehearsed to myself for five years before I played with another soul. That may account for some of my style. I knew that playing the blues was a life I chose to lead. And when I started there were three things I decided to doæplay the blues, play ’em right, and make all the gigs. And I have.

I’ve never drank liquor in my life or used dope, and I don’t allow it around me. That has a lot to do with why I’m still doing what I’m doing, still feeling good and still in good health. It makes me sick to see the things that people do to themselves when they get all messed up.

AP: Every 10 or 15 years there seems to be a blues renaissance, and people say there’s one happening now. Is it real?

KING: The blues “come back” whenever people realize that they can make money booking it. You didn’t hear about young bluesman for a while until Stevie Ray and Robert hit, but they were always around. It’s just a matter of exposure.

This interview originally appeared in Guitar World, July ’91.

Amazon.com Widgets

May 21, 2014

Gimme Three Chords – Inside Lynyrd Skynyrd’s greatest hits

Me and Gary Rossington, Beacon Theatre

This article was written for published in Guitar World a long, long time ago. Don’t forget to check out my book, One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

GIMME THREE CHORDS

Guitarist Gary Rossington explains the origins of some of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s—and rock’s—finest moments.

“We used a lot of D-C-G progressions,” Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist Gary Rossington says with a shrug and a laugh about his band’s songwriting process. “There’s only seven chords, so you got to use the same ones over. It’s all in what you do with them. I could a dozen different songs with the same three or four chords but they’d all be entirely different.”

Rossington and company certainly have always had a knack for doing a lot with a little. For while Skynyrd are renowned for their aggressive, three-guitar attack and the seemingly endless soloing such a lineup inevitably produces, what’s really made Skynyrd a staple of classic rock radio is their songs: instantly memorable four-minute rockers like “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Give Me Three Steps” and “What’s Your Name,” as well as extended ballads such as “Simple Man,” “Tuesday’s Gone,” and, of course, “Free Bird.” Remarkably, the latter, one of rock’s most-played, best-loved songs, was one of the first songs Lynyrd Skynyrd ever wrote—penned when singer Ronnie Van Zant and guitarists Allen Collins and Gary Rossington were still in their teens.

Like virtually all of their material, “Free Bird” was written as a collaboration between Van Zant and one the group’s guitarists. This loose but consistent formula served Skynyrd extremely well, producing classic songs which quickly made them one of the nation’s most popular bands. By 1975, however, when third guitarist Ed King left the group suffering from burnout, Skynyrd had fallen into a bit of a creative rut, as reflected by Gimme Back My Bullets, an unusually flaccid affair. Before anybody could write the band’s epitaph, however, they added guitarist Steve Gaines, whose songwriting and phenomenal playing infused them with a new energy. The rejuvenated band shines on 1976’s live One More For The Road and the following year’s Street Survivors. The latter is one of the best-arranged and played guitar albums in rock history.

Tragically, before the group could reap the fruits of this rebirth, their chartered plane crashed into a Mississippi swamp on October 20, 1977, killing three members—including Gaines and Van Zant—seriously injuring everyone else and seemingly forever putting an end to the group.

A decade later, the surviving members of the group got together for a “Tribute” tour with Van Zant’s brother, Johnnie, taking over as vocalist. Enthusiastic audience response led to a full-time reunion. Rossington recalled the origins of some of the band’s best-loved tunes.

“FREE BIRD” -

pronounced leh-nerd skin-nerd (MCA, 1973)

“FREE BIRD” -

pronounced leh-nerd skin-nerd (MCA, 1973)

“I don’t remember that one. Could you sing it for me? Oh, okay. Allen had the chords for the beginning, pretty part for two full years. We were just beginning to write—that was actually one of the first songs we ever completed—and Ronnie kept saying that there were too many chords so he couldn’t find a melody for it. He thought that he had to change with every chord change. We kept asking him to write something to these chords and he kept telling us to forget about it!

“Then one day we were at rehearsal and Allen started playing those chords, and Ronnie said, ‘Those are pretty. Play them again.’ Allen played it again, and Ronnie said, ‘Okay, I got it.’ And he wrote the lyrics in three or four minutes—the whole damned thing! He came up with a lot of stuff that way, and he never wrote anything down. His motto was if you can’t remember it, it’s not worth remembering.

“So we started playing it in clubs, but it was just the slow part. Then Ronnie said, ‘Why don’t you do something at the end of that so I can take a break for a few minutes.’ So I came up with those three chords at the end and Allen played over them, then I soloed and then he soloed. It all evolved out of a jam one night. So we started playing it that way, but Ronnie kept saying, ‘It’s not long enough. Make it longer.’ Because we were playing three or four sets a night, and he was looking to fill it up. Then one of our roadies told us we should check out this piano part that another roadie, Billy Powell, had come up with as an intro for the song. We did–and he went from being a roadie to a member right then.

“Everybody told us that we were crazy to put the song on our first album, because it was too long. Our record company begged us not to include it. And when it first came out, they did all kind of awful edits until it got big enough where it didn’t matter any more. It humbles us to think that it’s been played so much—and it’s still played. But it’s not magic—it’s still just a song to us.”

“GIMME THREE STEPS” - pronounced leh-nerd skin-nerd (MCA, 1973)

“This is another true story. Ronnie went into a bar to look for someone and me and Allen were too young to get in so were waiting for him outside, and we were waiting and waiting, then he came running out with a big ol’ guy chasing him, yelling.

“He had started dancing with this chick and this guy came in and was going to beat him up and Ronnie said, ‘Just give me three steps and I’m gone.’ The guy had a gun and he was a redneck and he was drunk—a nasty combination of things—and Ronnie said, ‘If you’re going to shoot me, it’s going to be in the ass or the in the elbow.’ And he took off like a bat out of hell.

“We got in the car and split and he told us what happened and we were laughing and we kind of wrote the song right there, drove over to Allen’s house, got his guitar and finished it.

“The more wild experiences you have the better songs you can write. I’m not necessarily proud of everything we ever did, but that’s just true. We always just considered ourselves a working-man’s band and thought every song should tell a story that people could relate to. When we finish a song, you know what it’s about, whereas some groups have songs you may dig but not understand. I think that’s why our songs have lasted as long as they have.”

“SWEET HOME ALABAMA” -

Second Helping (MCA, 1974)

“SWEET HOME ALABAMA” -

Second Helping (MCA, 1974)

“I came up with the banjo/steel guitar part—it’s just a fingerpicked D,C,G progression—and the little opening riff , which I kept playing over and over again. Ronnie started writing lyrics at rehearsal one day and saying, ‘Play that again. Play that again.’ And after about an hour he had all the words. Then Ed [King] took it home and put in all the little fills and licks and arranged it.

“It was basically a joke song. We used to travel through Alabama a lot and get onto back roads and just marvel at how pretty it was and how nice the people were. And Neil Young was, and still is, one our favorite artists, so when he came out with ‘Southern Man’ and ‘Alabama,’ criticizing the South, we said, ‘Well what does he know? He’s from Canada!’ So we threw that line about him in there. We were told by some people to take out the parts about Neil Young and [former Alabama governor] George Wallace, but we said, ‘Hey it’s just a song. And we’re going to record it the way we wrote it.’

“Most of our songs come through us. It either happens real quick or it doesn’t happen at all. Actually, Ronnie wrote most of his lyrics either driving around Jacksonville checking out different neighborhoods—especially poor ones, black and white—or in the shower. You know how people sing in the shower? Well, Ronnie did that, but he made up songs—melody, verse, chorus, bridge and all. Many times when we were on the road, he’d end up running into my room with a towel around his waist, dripping wet, saying, ‘Check this out. Write some music to that real quick.’ So I’d try to write a few chords to get a rough idea of where the song was going, then either Allen or Ed or I would go back and finish the song.”

“WEREWOLVES OF LONDON” - (Warren Zevon, Excitable Boy, Elektra, 1978)

“This guy (Warren Zevon) used the same exact chord progression as ‘Sweet Home Alabama.’ I mean, you could sing ‘Alabama’ to his song. It doesn’t bother me at all. I can’t think of any examples, but I’m sure we did the same thing to somebody at some time. I think it’s fine.”

“CALL ME THE BREEZE” - Second Helping (MCA, 1974)

“We always liked J.J. Cale and we heard ‘Breeze’ one night sitting around the house and Ronnie said, ‘Let’s do that!’ But it didn’t worked the way he did it—a real straight shuffle—so I wrote the arrangement, which was completely different. If we had changed the lyrics, it would have been a completely different song. We did the same thing to Merle Haggard’s ‘Honky Tonk Night Man.’”

“CROSSROADS” - One More For The Road (MCA, 1976)

“We did that as a tribute to Cream, one of our all-time favorite bands. We saw them on their Farewell tour and they completely blew our minds, so we made this a regular part of our set. In fact, it was our encore for years, until ‘Freebird’ became so big that we basically had to do that last. By the time we recorded the live album, it had been such a part of our set for so long that we felt we had to include it. Also, our producer, Tom Dowd, engineered the Cream version and he told us the story about how it came together, and that really inspired us to want to re-record it.“

“I KNOW A LITTLE” and “YOU GOT THAT RIGHT” - Street Survivors (MCA, 1977)

“I think these two songs sum up what Steve Gaines meant to the band. He wrote both of them and sang ‘You Got That Right’ as a duet with Ronnie. He was a great songwriter and singer–and an incredible guitarist. I’ve never heard anybody, including any of us, play the picking he did on ‘I Know A Little’ quite right. Steve had a lot to do with the writing and arrangements throughout this album and his playing was so good it really inspired us. When he joined, we were kind of an in a lull. We were still doing well—selling a lot of tickets and records—but the music was getting a little boring to us. We needed a little spark of inspiration, and Steve provided it. We started getting together and jamming at night. It put us back in the frame of mind we had had at the beginning.

“Steve was so good, he was a freak of nature. He used to piss us off because he could do so many things that me and Allen couldn’t. Every time I ever went to his house or his hotel room, he had his black Les Paul on. He’d order room service and eat with his guitar on. He’d sit around and talk and not play it for an hour, but it would be strapped on. He’d watch TV with it on, play it during commercials, then stop. It was like his third arm.”

“HONKY TONK NIGHT TIME MAN” - Street Survivors (MCA, 1977)

“This is a Merle Haggard song, which we did to show our love for him and for country music in general. Steve played an incredible solo here also, and it was a live first take. We only knew that it was a G progression and he went out and played a mind-boggling solo. He didn’t even hardly know the song, but he played the shit out of it. We were standing in the control room with our jaws dropped, and he strolled in and said, ‘How’d I do?’ We told him to go home and call it a day, because we knew it couldn’t get any better.”

“WHAT’S YOUR NAME” - Street Survivors (MCA, 1977)

“Me and Ronnie were just sitting in a hotel room one night and I had those chords which I had just written that day. And he right off the bat started singing. The original lyrics were, ‘It’s eight o’clock and boy is it time to go.’ Ronnie had just gotten an itinerary from his brother Donnie, who was in .38 Special and their first stop was Boise, Idaho. So Ronnie changed the first line to ‘It’s eight o clock in Boise, Idaho,’ which immediately made it a real on-the-road song.

“But it’s all basically a true story. One of our road crew got in a fight at a bar with one of the hotel guests and they kicked us out, and we said we’d leave if they’d send a bottle of champagne to our room. It’s just about being young and free—21 and unmarried. We’d go to a town and meet a chick, then forget her name. And when you’d come back to town, you’d say, ‘What was your name, honey?’”

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

May 8, 2014

From the archives: Dickey Betts and his custom Gibsons

In 2001, I went out to Long Island to introduce Dickey Betts to Andy Aledort, who would be working with him on a column for Guitar World. Dickey only wanted to do interviews with me, but I assured him that if he met Andy he would love him. That was the beginning of a beautiful friendship; Andy has now been playing with Dickey for about 8 years.

After we did the interview at Dickey’s hotel room, we hung out all night and eventually outside the Westbury Music Fair, where he would be performing, Dickey showed us the prototypes of his upcoming Gibson signature guitars. Here’s the story I wrote.

Dickey showing off the prototypes on his bus, 2001. Rare time when a photo captures the interview. Photo by Andy Aledort.

“Look at this thing, man! It’s beautiful!” Dickey Betts stands in the back bedroom of his tour bus and thrusts forward a gorgeous Gold top. If you didn’t know better, you’d swear it was Goldie, his famous ’57 Les Paul which he played in the Allman Brothers Band for over 20 years. Except that Goldie is, in fact, sitting just a few feet away and is actually no longer gold. (More on that in a moment.)

“This is a ’57 reissue from the Gibson Custom Shop, a prototype of my signature guitar, and it’s a great instrument,” Betts says. “People don’t have to spend 25 or 30 grand to get a vintage guitar any more. This is just as good and I’m very proud that it is going to have my name on it.”

The Dickey Betts Signature Series will eventually feature two models. The first one, an “aged” ’57 reissue Gold top based on the instrument Betts proudly showed off, was introduced in July. Each of them is made in the Gibson Custom Shop then hand-finished by Tom Murphy, a luthier famous for his uncanny ability to match a vintage finish. Vintage lovers will be overwhelmed by the guitars’ uncanny resemblance to a decades-old instrument, but for Betts esthetics are a distant second to playability.

“What I care about is how a guitar sounds and feels and as soon as I picked a few notes unplugged on this, I knew it was a great one,” Betts says. “It’s got great wood and a great finish, which lets the sound ring rather than stifling it. I think I might actually like it more than Goldie now.”

Oddly, Goldie is now a beautiful redtop since Betts himself stripped it and refinished it several years ago. “It had been really worn down by all the use and I just decided to make it how I wanted it,” Betts explains. “Some people think it’s nuts to do something like this to such a valuable guitar, but it’s a working tool for me.”

Betts also recurved the pickguard by hand to better suit his needs, then lowered its profile. He dressed up the hardware by adding a sterling silver Indian belt buckle to the input jack and a silver ring to the toggle switch cover. All of this will be recaptured on the second line of Dickey Betts signature guitars.

“We are going to take Goldie to the shop and put the micrometers on it,” says Rick Gembar, general manager of Gibson’s Custom Shop. “The Dickey Betts redtop will feature all the little things particular to his instrument. These are some of the ultimate guitars on the planet.”