Alan Paul's Blog, page 32

October 14, 2014

Neil Young on Howard Stern

Neil Young visited Howard Stern for an interview this morning. They covered a lot of ground, including why he thinks Buffalo Springfield’s music didn’t translate well to record, the act and art of songwriting, bad reviews, and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. Young doesn’t even want to mention David Crosby by name. When Stern asks if it would break his spirit to tour with CSNY again, Young replies, “It would never happen, so it’s nothing to worry about… Why get together to celebrate how great we were?

…”When you play music, you have to come from a certain place and everything has to be clear. I don’t want to disturb that. The love has to be there.”

Amazingly, it is also revealed that he can’t tune a guitar. NEIL YOUNG CAN NOT TUNE A FUCKIN’ GUITAR. That’s crazy.

Listen to the entire 75-minute interview below.

Commentary on this from Bob Lefsetz:

What an original!

We’ve been told that selling out is a choice. But the truth is Neil Young is just wired different. You can’t emulate him, because you’re not him.

This interview was very slow to get going. Because Neil was reluctant. And he was mimicking his hero Bob Dylan, refusing to explain his songs and obfuscating in interviews. But then Neil started revealing his choices and they were so different from everybody else’s that you couldn’t help but marvel.

Like being pissed at the cameramen at Woodstock, to the point of yelling for him to get off the stage, the result being Neil’s absence from the movie. But he didn’t care.

And this is fascinating, because dedicated Stern listeners know that Leslie West believes his career cratered as a result of not being in the flick, that his manager’s decision for Mountain not to be in the movie hurt him forevermore.

But then there was the refusal to be on the “Tonight Show” with Buffalo Springfield because it wasn’t their audience. Can you imagine that today? Someone refusing to do press because the audience might not be right? Ever since the Police the goal is world domination, and if you’re not interested, I’m gonna beat you over the head and convince you.

And then the refusal to get back together with CS&N. Sure, he’s got a feud with Crosby, but even more interesting was the lack of motivation. Howard talked about the fans, Neil didn’t care about the fans, he cared about the music, to go play the greatest hits so people could hear them and everybody could make money held no interest.

And then Neil unloaded on AGT. He repeated it a few times, wondered why Howard Stern did the show.

And that’s when the gap was fully evident. Neil Young was refusing to play the game. He wasn’t gonna come on and reveal all his warts and make like they’re all friends just to sell his latest forgettable product.

And let’s be clear, that is why he was on, to flog Pono and his book and his album, which is kind of sad, I’d be more impressed if Neil dropped by with nothing to sell, but in these moments the divide between broadcaster and talent, between talker and singer, between performer and artist, could not have been more evident. Neil Young was gonna be himself, he could only be himself, and it made Howard and his show look small.

That’s how it used to be, when musicians were giants who walked the earth towering over all other media. Before the best and the brightest went into tech and all we got was an endless parade of yes people willing to bend over to get reamed by not only the industry but the corporations. Who can believe in people like that?

And sure, there was some detailing of how the songs came together, but to say this interview was great would be to overestimate it. At the end it finally flew, Neil relaxed, didn’t deny he was dating Daryl Hannah, said he loved to paddle board, but this was not a morning in the clubhouse so much as a glimpse into the mind of an artist.

Who lives in his own head and doesn’t follow the charts and has no idea of this popular culture of which you speak because he’s doing his own thing.

And I don’t agree with all of Neil’s choices, nor do I think much of his recent material is genius. Then again, even he thinks he’s repeating himself.

But you don’t often get a chance to peek into the brain of an original artist who impacted the culture and is still here, with his faculties intact, not retired, but continuing to push the envelope.

I implore everybody making music to listen to this interview. Not because it’s great, because, as I stated above, it’s not, but because it illustrates you’ve got choices.

You don’t have to write hits.

You don’t have to listen to your label.

Your manager’s job is to free you up, to respect your wishes, to allow you time to create.

We’re so far from the garden I doubt we can ever get back.

There will always be music.

But that does not mean it will be art.

Art requires artists. Who question. Who take chances. Who hew to the vibrations of their own inner tuning fork, who we pay attention to because of their strength in following their vision, in continuing to search without compromise.

Whew. It was definitely Neil.

But he was definitely not like anybody else.

October 3, 2014

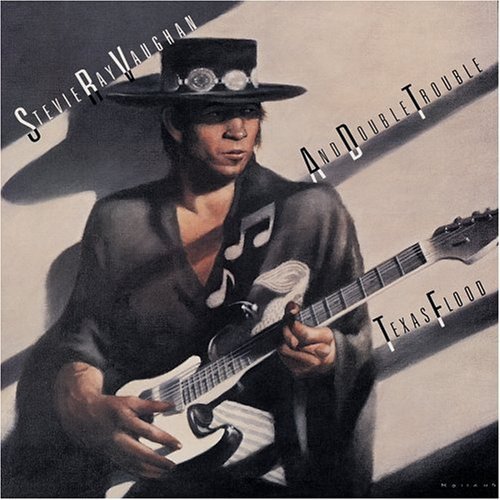

The Making of Texas Flood

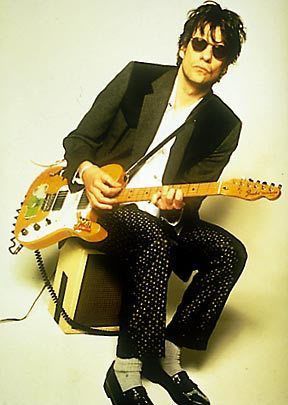

SRV, by Kirk West – www.kirkwestphotography.com

In honor of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s 60th birthday, I present the following story of the making of Texas Flood. This was written for and originally published in Mojo circa 2001. A new version of the album was released last year: Texas Flood (30th Anniversary Collection).

When Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble were booked to play the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival, it seemed that years of gigging and hard work had paid off. At last, the Texans who had spent years touring in a milk truck that leaked oil had gotten their break, becoming the first unsigned act to play the prestigious fest. It was a long way from the small clubs the trio played back home in Austin.

The booking came about thanks to the intervention of music industry big wig Jerry Wexler, who saw Vaughan and DT perform at a record release party for their former bandmate, singer Lou Ann Barton, and pledged to help. True to his word, Wexler had called his friend Claude Nobs, the Montreux promoter and helped secure them a slot. Vaughan and Double Trouble appeared on July 17, 1982, at the Montreux Casino amidst an evening of acoustic blues and the audience was less than impressed with their fiery, rocked-up show. Vaughan opened with Freddie King’s instrumental “Hide Away” and tore thorough staples-to-be like “Pride and Joy, “Texas Flood” and “Dirty Pool.”

Any blues fan today would give their eye’s tooth to witness this show. But the Montreux crowd, not expecting such a blistering assault on their evening and perhaps put off by Vaughan’s unabashed swagger and the simple fact that he was white, was les than enthusiastic. In fact, a good portion of the people present booed while the rest were oddly silent. The show can be seen in its entirety on the two-DVD set, Live At Montreux, 1982 & 1985 (which also includes the band’s triumphant return three years later, as superstars). Watching it now, it is impossible to fathom what the audience was thinking in their tepid-at-best reaction. It is not, however, hard to imagine the crushing disappointment Vaughan must have felt.

“Stevie was broken-hearted,” recalls bassist Tommy Shannon. “He turned around and said, ‘I don’t think we sounded that bad.’”

Adds drummer Chris Layton, “After the show we felt depressed and bewildered. We had come so far with such high expectations and the response was so bad.”

Photographer Darryl Pitt recalls rushing backstage to console Vaughan, only to find him slumped on a small road case, looking like he had “been hit by a sledgehammer.” The dejection did not last long, however. The band was sitting glumly around its tiny dressing room when a Festival employee stopped by and said that David Bowie was in the house and wanted to meet them all.

Photographer Darryl Pitt recalls rushing backstage to console Vaughan, only to find him slumped on a small road case, looking like he had “been hit by a sledgehammer.” The dejection did not last long, however. The band was sitting glumly around its tiny dressing room when a Festival employee stopped by and said that David Bowie was in the house and wanted to meet them all.

“We sort of went, ‘David Bowie who?’” recalls Layton with a laugh. “And the guy said, ‘You know, David Bowie.’”

Vaughan, Layton and Shannon headed for the Musician’s Bar downstairs, where they hung out and chatted with Bowie for hours. Vaughan was, of course, delighted with the attentions of Bowie, who would soon proclaim the Texan the best urban blues player he’d ever heard and proclaim that no guitar player had juiced him up so much since he saw Jeff Beck in the early 60s at a London club. But Bowie, too, was pleased that the guitar firebrand was paying so much attention to him. On the heels of Low, Heroes and Scary Monsters, Bowie was regarded as a rather fringe artist in America at the time. So it was that when the rock star asked the unknown guitar stud whether he would be interested in doing some recording, the singer was just as pleasantly surprised that the guitarist said yes as the guitarist was that the offer was made.

“I expected and would have understood a polite ‘Thanks but no thanks,’” Bowie writes in the liner notes for the Montreux DVD. “You can’t imagine how delighted I was when he accepted the offer on the spot and said he’d love to try out a new kind of record just for the experience.”

The following night, Vaughan and company were booked to play the same hotel bar. Jackson Browne, who had performed at the Fest earlier that night was doing an interview in his hotel room when several members of his band barged in bubbling with excitement, insisting that whatever Browne was doing, he had to stop it and get down to the bar right now. Following his bandmates downstairs, Browne was similarly awed by what he witnessed and soon climbed on stage.

Recalls Layton. “We played all night, with Jackson and his whole band sitting in. We jammed until seven a.m., and at the end of the night Jackson said that he had a studio in L.A. and we were welcome any time we wanted to come record some tracks free of charge.”

Over the next six months, the meetings with Browne and Bowie would launch the career of Vaughan and Double Trouble and change the course of blues guitar, bu that was far from clear when the band returned to Austin. They were poorer than a church mouse and their immediate prospects didn’t seem any more promising than they had for the past few years. Vaughan decided to take Browne up on his offer. The singer agreed to give the group 72 hours in Down Town over Thanksgiving weekend, 198, and they quickly booked a short tour to help cover their travel expenses. While most of the studio staff wanted nothing to do with helping some raggedy assed unknowns over a long holiday weekend, engineer Greg Ladanyi offered his services.

“We went in there, just hoping hoped that maybe we were making a demo that would actually be listened to by a real record company,” says Layton.

They were, in fact, recording their debut album, Texas Flood, though the circumstances hewed much more closely to their demo ideas.

“Down Town really was just a big warehouse with concrete floors and some rugs thrown down,” says Shannon. “We found a little corner, set up in a circle looking at and listening to each other and played like a live band.”

“We just rolled in there like it was a rehearsal or something and the guys working there were mildly annoyed because it was Thanksgiving weekend and they wanted to be home,” says Layton. “We were so unprepared, we were like, ‘Hey, uh, you guys got any tape?’”

Ladanyi offered up some used tape to record over, including some of the demos for Browne’s not-yet-released album Lawyers in Love. The trio basically just ran through a typical live set of their strongest tunes. Ladanyi was not interested in getting too deeply involved and the band was unsatisfied with their sound throughout the first day. Richard Mullen, a Texas musician and friend of the band who had been coming to their shows and running sound gratis, happened to be in town, recording with singer Christopher Cross. Not wanting to ruffle any feathers and grateful for the free time, Vaughan had not pushed when Browne and Ladanyi balked at having an outsider behind the console, but by the time they broke for dinner on the first night, the guitarist was vocally upset with his mates about the results. Mullen replied by urging the shy frontman to exert his will, saying in essence, “This is your shot and your show and if you want anything to be different, you have to speak up.”

Returning to the studio newly emboldened, they found that Ladanyi had left. In his place was an assistant, who did not think his job involved more than “pushing the stop and record and buttons.” So Mullen took over, tuned the drums and dialed up the sounds he wanted to hear on Vaughan and Shannon’s amps. He also employed some sound baffles between the players to decrease leakage and allow cleaner tracks of each instrument without forcing the band to physically separate and lose their live vibe. From then on, the band rolled through their repertoire, recording two songs that night and eight the following day. There is some dispute about whether Mullen appeared at the end of the first day or the beginning of the second and whether the whole session lasted two or three days. In any case, they definitely did record seven of the album’s eventual 10 tracks on a single day, November 24, 1982, when they also cut “Tin Pan Alley,” a blues classic that was an SRV standard and which appears on Sony’s 1999 remastered version of Texas Flood. Vaughan cut only scratch vocals, adding only these tracks back at Mullen’s Austin studio.

“That whole recording was just so pure; the whole experience couldn’t have been more innocent or naïve,” says Layton. “We were just playing. If we had known what was going to happen with it all, we might have screwed up. But we just went in there and did our live show. The magic was there and it came through on the tape.

“It’s funny, too, because people tell me all the time how much they love Stevie’s tone on that album and ask how he got it. It was so simple it’s ridiculous; he plugged his Strat into ‘Mother Dumble,’ a Dumble amp that Jackson owned and we found in the studio.”

THE ORIGINAL “TEXAS FLOOD” BY LARRY DAVIS:

Vaughan’s hard-edged, vintage sound would soon turn the guitar world’s perception of tone on its head. At the time, rock music seemed eager to leave the past behind. Indeed, many thought guitars passé, with futurists proclaiming that the instrument would be permanently transformed by MIDI applications and replaced as rock’s dominant instrument by the synthesizer. Even many guitar loyalists thought the classic sounds were no longer adequate, transforming their instruments by running them through racks of elaborate, high-tech gear to create heavily processed sounds. Odd-shaped, brightly colored axes were all the rage.

Vaughan’s gear throughout his career was profoundly old school and never more so than on Texas Flood. Eventually, the tones he coaxed from his old but timeless gear would ignite a vintage craze that rages to this day and also launch a new market for small, high-end boutique amplifiers that replicated classic sounds with modern conveniences.

Following the recording sessions, the group stayed in LA to play several dates. On one of these nights, Layton was awakened at the Oakland Gardens Hotel by a three am phone call. “I answered in a fog and it was a guy with an English accent asking for Stevie,” Layton recalls. “I said that he was sleeping and asked who was calling. He goes, ‘It’s David Bowie and I’d like to speak to him now if possible. I got Stevie up and Bowie asked him if he wanted to come to New York and cut some tracks.”

Vaughan accepted the offer and flew to New York in the third week of December to join Bowie and producer Nile Rodgers at the Power Studio. Let’s Dance was complete except for lead guitar tracks. Vaughan’s performances, Bowie has said, “ripped up everything everyone thought about dance records.” Vaughan had casually become the linchpin in birthing a sound that Bowie had long heard in his head – a new kind of dance music that combined Euro sensibility with raw American blues power. Blown away, Bowie quickly asked Vaughan to join his touring band and the offer was accepted, though not without some real angst about leaving behind his own group.

“Stevie‘s plan was to do it for a year, take the money and pay us to keep the band together,” Shannon says.

As rehearsals continued in Dallas, then New York, Bowie and his band grew increasingly excited about the sound they were crafting around Vaughan’s blistering lead work and anticipation rose for bringing this heady brew around the world.. It was not to be, however.

What happened next is not entirely clear. Bowie says that as the band was literally loading onto a bus to go to the airport and fly to Europe and commence touring, Vaughan’s manager demanded a much higher salary or else the guitarist would not tour. The offer was promptly rejected, leaving the guitarist and his bags stranded on the sidewalk as the bus pulled away without him. Layton and Shannon have different recollections of the event. They say that Vaughan, already uncomfortable in a sideman’s role and upset that several promises about opening some shows himself were broken, finally snapped when told that he couldn’t mention his own band or music in interviews.

“He just couldn’t do it because it wasn’t what he loved playing,” Shannon says. “He liked David and his music, but it wasn’t where he was headed and Stevie could not do what he didn’t love.”

Whatever the exact circumstances, Vaughan most definitely did quit Bowie on the eve of a huge world tour to return to Double Trouble and their oil-leaking milk truck.

“I really wasn’t surprised when Stevie quit, but I sure was happy,” recalls Layton. “I couldn’t believe that just when we seemed to have all this momentum, Stevie was going to be gone for at least a year, maybe more. We really thought it might be over, right when we had worked so hard to get to that point, where it seemed like something was going to happen.”

Something was, in fact, already happening. Urged on by Layton and Shannon, who were feeling increasingly desperate that their moment was passing, manager Chesley Millikin had been shopping the 10-song tape made at Browne’s studio and found an admirer in John Hammond. The septuagenarian A&R man, whose discoveries and signings included Billie Holliday, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, took the tapes to Epic and essentially demanded they sign him. Just like that, and with little other label interest, Vaughan quickly had a deal with Epic Records.

“Epic wanted to release our demo right away and we got more attention because people wanted to know who this unknown guy who told David Bowie to take a hike was,” says Layton.

Vaughan’s pungent playing on Let’s Dance, redolent of Albert King, garnered attention as well, from fans and fellow musicians alike.

“I was driving and ‘Let’s Dance’ came on the radio,” recalls Eric Clapton. “I stopped my car and said, ‘I have to know who this guitar player is today. Not tomorrow, but today.’ That has only happened to me three or four times ever, and probably not for anyone in between Duane Allman and Stevie.”

With Hammond on board as Executive Producer, Vaughan cut new vocals for “I’m Cryin’” before the album was mixed at New York’s Media Sound and released on June 13, 1983.

“We started touring behind Texas Flood and we could feel things changing, the crowds slowly getting bigger and bigger,” says Shannon. “Then we got rid of the milk truck and got a bus and we were in heaven — even though it was a really shitty bus.”

Adds Layton, “We toured the whole country, playing every night, selling out 500 seat clubs, with 200 people standing outside trying to get in. We could feel this incredible momentum building.”

“What really brought it all home for me was when we played at the Palace in Hollywood,” adds Shannon. “We had played there before to mediocre crowds and this time there was a line stretching down the street and around the corner.” (Three songs from the September 23, 1983, performance at the Palace are featured on the remastered Texas Flood.)

Proof that Vaughan was entering the music mainstream came when the album was nominated for two Grammys: Best Traditional Blues Recording and Best Rock Instrumental Performance (for “Rude Mood”). The band also appeared on the Austin City Limits television show and Vaughan won three categories in Guitar Player magazine’s Readers Poll: “Best New Talent”, “Best Blues Album”, and “Best Electric Blues Guitarist,” an award he would win every year until his death. MTV was still fairly new and quite wide open and they began playing the video for “Pride and Joy.” In retrospect, given the strength of the album, all this success seems obvious, but in 1983, it was anything but. A reasonable betting man would have wagered his house that Vaughan and his old school blues-rock trio would fail to register on the popular culture’s radar screen. But the 29-year-old guitar firebrand was clearly playing by his own set of rules. “He was a leader, not a follower,” notes B.B. King “and you didn’t have to be a guitar expert to know that.”

Texas Flood blew open the locked doors of popular music and proclaimed that blues could be a potent commercial force. The album, combined with the runaway success of Let’s Dance, not only put the unknown Texan on the map but also signaled that uncompromised, from-the-gut guitar music was not dead as a commercial and artistic force.

“Stevie Ray Vaughan single-handedly brought guitar- and blues-oriented music back to the marketplace,” recalls Dickey Betts, whose Allman Brothers Band were prominent casualties of the era’s anti-roots disease. “He was just so good and strong that he would not be denied. When I heard ‘Pride and Joy’ on the radio, I said ‘Hallelujah.’”

Vaughan’s dramatic arrival not only helped smooth the way for the return of classic blues-oriented rock acts like the Allman Brothers, but it also made the environment more hospitable for his own peers, including The Fabulous Thunderbirds (featuring big brother Jimmie Vaughan), Robert Cray, and Los Lobos, all of whom had hits in the years following Texas Flood. Stevie also shone a bright spotlight back on his original heroes, most of whom had been languishing — overlooked and usually sans record deal. Albert King, Buddy Guy, Lonnie Mack, Hubert Sumlin, Otis Rush and Albert Collins suddenly found themselves once again being hailed as guitar titans, with interest in their music skyrocketing to levels unseen since the white rock audience’s initial discovery of blues in the 1960’s.

Certainly, as he himself pointed out, Vaughan owed a huge debt to these originators, but his music was not simply derivative; he hungrily swallowed his influences, fully digested them and crafted a style uniquely his own. In so doing, he succeeded where countless others had failed — reinventing the blues in a manner both visionary and true to the original material. It was a goal shared by every hippie with a Muddy Waters record but accomplished by precious few.

“Stevie’s playing just flowed,” says B.B. King. “He never had to stop to think. His execution was flawless, and his feel was impeccable. Stevie could play as fast as anyone, but he never lost that feel.”

Adds Bonnie Raitt, a longtime friend of Vaughan’s, “Just when you thought there wasn’t any other way to make this stuff your own, he came along and blew that theory to bits. Soul is an overused word, but the fire and passion with which he invested everything he touched was just astounding, as was the way in which he synthesized his influences and turned them into something so fiercely personal.”

The word about Vaughan was out on the blues circuit for years, Raitt adds. Guy, King, Dr. John and others who passed through Austin had long been telling her about this kid who “was just killing it.” With the release of Texas Flood, the rest of the world got hipped as well.

// ]]>

September 27, 2014

Frank Fenter Honored By The Georgia Music Hall Of Fame

Frank Fenter Honored By The Georgia Music Hall Of Fame

Frank Fenter co-founder of Macon’s Capricorn Records

to be inducted into the Georgia Music Hall Of Fame

October 11th, 2014

Frank Fenter was born in South Africa, in 1936. He majored in drama at college in South Africa and planned to pursue an acting career. In 1958 Frank immigrated to London to further his dream.

Music was always a big part of Frank�s life and in London he became involved in the music business, he first booked groups into the music and club scene, then joined Chapell Music Publishing and later Frank headed ARC/Chess Music.

In 1966, Mr. Fenter became Head of Atlantic Records in the United Kingdom and within six months, was at Atlantics� helm for all of Europe. Under his leadership, Frank Fenter helped sign and launch the careers of YES, Led Zeppelin, and King Crimson, making Atlantic the most important US label in promoting British Rock N Roll music to the world.

In 1967, Frank Fenter brought Atlantics’ R & B artists, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Eddie Floyd and Carla Thomas to Europe in the renowned �Hit the Road Stax� tour of 1967, which was important in crossing over Otis Redding to a white mainstream audience; it was further helped when Fenter suggested to Atlantic Record�s producer, Tom Dowd, to record the live European tour with the majority of the recordings released to critical and commercial success.

In 1969, Frank Fenter went on to become a co-founder and partner in Capricorn Records, the new label introduced �Southern Rock� and launched the careers of The Allman Brothers Band, Wet Willie, The Marshall Tucker Band and Elvin Bishop among others, into commercial prominence and making Capricorn Records one of the most successful independent record companies in America.

September 22, 2014

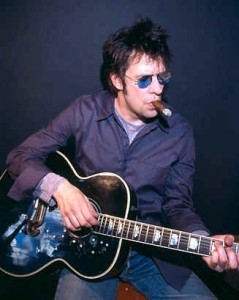

A (pretty damn good) interview with Paul Westerbeg

In honor the Replacements’ recent reunion shows, I present to you this interview with Paul Westerberg. I would have loved to go see them in Queens Friday night, but I had my own gig going on.

In honor the Replacements’ recent reunion shows, I present to you this interview with Paul Westerberg. I would have loved to go see them in Queens Friday night, but I had my own gig going on.

The Replacements were a very important band to me. I saw them in September, 1984, at the late and lamented Joe’s Star Lounge, weeks after arriving in Ann Arbor as a freshman. Per Hoffman – now one of my oldest friends, then a new and exciting acquaintance – told me that his friends were talking endlessly about the Replacements and we had to go. I was sold by the Village Voice quote on the poster which was plastered all around town – something like, “the dream flannel amalgamation of CCR and the Ramones.” Sounded good, and they delivered.

It was my introduction to a whole other world of music, and it helped open my eyes to a burgeoning alternative world. I turned away from most of it and back towards blues and other roots music before long, but the best Replacements music has stuck with me, because I think it transcends its time and genre, and that’s because Paul Westerberg wrote some really great songs.

I consider this 1996 interview with Westerberg something of a lost classic – lost even to me. I was very happy with it at the time, but sort of forgot about it and when I came back across it I was honestly taken aback by how good it is. I’m really pleased to have found it and to have the opportunity to share it again. And I’m proud to have been the one to get Westerberg to tell his secret – he always wanted to be a blues guitarist. I knew there was something different in his music.

Last spring, Paul Westerberg and Brendan O’Brien entered an Atlanta studio to record Westerberg’s second solo album. Some observors hoped that working with O’Brien, the über-producer who has worked with Stone Temple Pilots, Pearl Jam and the Black Crowes, might bring Westerberg the hit record which has always eluded him. Two weeks later, the former Replacements’ frontman was on a plane home to Minneapolis, with most of the tracks he and O’Brien had worked on left to gather dust.

Last spring, Paul Westerberg and Brendan O’Brien entered an Atlanta studio to record Westerberg’s second solo album. Some observors hoped that working with O’Brien, the über-producer who has worked with Stone Temple Pilots, Pearl Jam and the Black Crowes, might bring Westerberg the hit record which has always eluded him. Two weeks later, the former Replacements’ frontman was on a plane home to Minneapolis, with most of the tracks he and O’Brien had worked on left to gather dust.

“It just wasn’t shaping up to be as good a record as I knew it could be,” Westerberg says. “Sometimes you just have to know when to pack it in and try over.”

Once an iconoclast, always an iconoclast.

Westerberg enlisted Lou Giordano (Goo Goo Dolls, Sugar, Smithereens) to help him finish up. The result is Eventually (Reprise), the title apparently a reference to the three years that have elapsed since his solo debut, 14 Songs (Sire/Reprise). Despite the start and stop recording process, the album sounds spontaneous and fresh. Westerberg is again the sole guitarist, and the instrument comes more to the fore here, with a chiming 12-string on “These Are The Days,” careening fills on “Century,” layers of acoustics and electrics on “Love Untold” and a pretty, liquid-toned lead line on “Once Around The Weekend.”

Some of his rockers now sound formulaic—even he admits, of Eventually ‘s “You’ve Had It With You,” “I’ve written that same song about 15 times now.” But Westerberg’s touch with subtler fare remains deft, as evidenced by acoustic-based gems like “Hide N Seekin,” “Angels Walk,” “Time Flies Tomorrow” and “Good Day,” a moving tribute to Replacements guitarist Bob Stinson, whose 1995 death seemed sadly inevitable.

The strength of the new album’s mellower tunes isn’t really a departure for Westerberg. For, while the Replacements were known for their drunken antics and unpredictable live shows, what actually set them apart in the early-Eighties alternative scene was their knack for balancing careening rockers with Westerberg’s aching, vulnerable ballads. This yin and yang was fully realized on albums like Let It Be (Twin/Tone,1984), Tim (Sire, 1985) and Pleased To Meet Me (Sire, 1987), landmark albums which largely failed to find a larger audience.

But just because the band never became stars doesn’t mean they didn’t leave a mark. Their melding of punk aggression and pop hooks became a touchstone for legions of alternative bands. Kurt Cobain, for one, was a major acolyte, taking much of his frayed flannel vulnerability, as well as the pained, nicotine and vinegar singing, from Westerberg. (He also borrowed the title of Nirvana’s Geffen debut, “Nevermind,” from a Replacements song.) All of which has left Westerberg with a strange niche in the rock world, someone who skipped stardom on the way to becoming a legend. It seems to be enough for him.

“I don’t have anything to prove these days except that I can still make meaningful music,” Westerberg says. “I can’t get hung up about how they’re going to sell anymore. Whatever happens, I’ll just tour for a while, then record another one. That’s what I do.”

GUITAR WORLD: Did you start out intending to be a guitarist or a songwriter?

PAUL WESTERBERG: A guitarist. I spent years sitting in my room listening to stuff with hot guitar players, like Duane Allman or Mick Taylor, trying to learn riffs. I fancied myself a lead guitar player until I was 19. Then I realized I sucked and that being a lead player just wasn’t going to get me where I wanted to go.

GW: Did playing with Bob make you realize that quicker?

WESTERBERG: Not really. When the Replacements asked me to join, it was expressly to be the lead guitarist. Things developed as they did somewhat out of necessity. Bob couldn’t sing a lick and he couldn’t write a song. I knew where to steal from and looked kind of reasonable standing in front of a mic, and we took it from there. Bob became the lead guitarist simply because he could not sing. Nor could Tommy [Stinson, bassist and Bob’s brother], who was 13 and whose voice hadn’t even changed yet. I learned to do what I do because I had to. If I didn’t do it, they would have gotten someone else to do it…and I liked their sister. [laughs]

GW: So it was the Stinsons’ sister that drew you to them?

WESTERBERG: That was a big part of it. I definitely wouldn’t have come back a second time if it wasn’t for her.

GW: Did being a frontperson come naturally to you?

WESTERBERG: Hell, no. It still doesn’t. My knees shake before every performance. It didn’t come naturally at all. I was terrified. I commanded the basement for a long time before we ever confronted an audience. Then it was like starting over again—with people responding to your singing by throwing things at you.

Fear of performing was quickly exchanged for fear of the audience. We were thrust into the punk scene, where if you weren’t good and weren’t sure of yourself, you would literally be physically attacked. So we had to get good real fast. Our survival instinct took over.

GW: Actually, listening back to Sorry, Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash [Twin/Tone, 1981], I was struck by how tight you guys were on your very first album—much more so than the reputation indicates.

GW: Actually, listening back to Sorry, Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash [Twin/Tone, 1981], I was struck by how tight you guys were on your very first album—much more so than the reputation indicates.

WESTERBERG: That stemmed from utter fear. We didn’t know what we were doing, and we were really scared of failure. We practiced really, really hard before recording the first album. We learned our parts and we learned complementary parts, and we made sure that everything meshed. It wasn’t until two or three albums later, after we had toured quite a bit, that we realized not everyone cares so much about notes, that your attitude and what you say and wear on stage is a big part of it too. As we learned to put on a show, the meticulousness of the songs and the playing tended to change—or suffer, depending on how you see it.

GW: Did the Replacements’ reputation for inspired drunken mayhem become a trap?

WESTERBERG: Of course it did, though we didn’t realize it at the time. We drank to give us courage and once we had courage we did zany things to make people remember us. And once they remembered us we started to write good songs and play better but it always seemed to be overshadowed by the zany things we did. We just couldn’t up the ante that last time. We didn’t know where to take it because we had created this albatross. That’s why the band broke up—there was nothing left to do.

GW: Why do you think critics liked the Replacements so much?

WESTERBERG: Because we never made it. If we had sold a million records, most of them would have abandoned us real fast. I know that they still like U2, but we didn’t have that kind of integrity or sophistication. We were just a good fuckin’ time. Then we started taking the whole thing seriously and that was the kiss of death.

GW: You guys were very different from the type of acts that a major label was used to working with in 1985. Do you feel that you were sort of put into a slum there?

WESTERBERG: To a certain extent, but to be fair, they did give us a chance with Pleased To Meet Me. But no one really spelled out what was required of us. A few years later bands like Guns N’ Roses promoted themselves on a major label with our style of behavior, but we were still of an era where misbehaving was not something that the label could tolerate or promote. I think they thought we were just pretending to be what we were and what we really wanted to do was sell a million records and live the good life. I think they were kind of shocked when they realized that we were what we were.

GW: Are you saying you didn’t want to sell a lot of records?

WESTERBERG: I’m saying we wanted to do what we were doing. If that sold a million records, wonderful. But they wanted us to change and toe the line and that tore us apart. Each individual band member went through this trauma: “Do we change what we do?” The problem deepened because we began to realize that our behavior had become old hat and we had to change, but we felt trapped that if we did change, it would look like we did it because the label told us to, and we’d lose credibility and everyone would say we sold out. We suffered a lot for that.

GW: That seems somewhat silly now, but at the time, many considered the mere act of signing with a major to be an act of treason.

WESTERBERG: You resent where you’re going because it means you have to leave where you came from behind. I’ve often wondered how our music would have been effected had we never signed to a major label, and I really think it would have gotten slicker quicker. I think if anything we tried to keep it as rough as possible for as long as possible because we felt somehow dishonored by being on a major label. I mean, we always loved pure pop music. We would have made that kind of music from day one, had we been capable of it

GW: Did Bob love that stuff, also?

WESTERBERG: Oh sure. You shouldn’t confuse what Bob liked with what he was capable of playing as a guitarist. He was great at playing one style, but he loved lots of other music.

GW: Were your ballads immediately accepted by the others?

WESTERBERG: Rarely was there a song that we all thought was great. There was tension pretty much every day over everything. [laughs] And, yes, as a rule, Bob preferred the high voltage stuff but I knew that sticking to that was going to lead us to a quick end, because we weren’t the best at it. Black Flag, Hüsker Dü and Minor Threat were our contemporaries, whether we wanted them or not, and they did that better than us. There was also R.E.M. I think it was very good for us to see a band that could retain their credibility while playing softer music, but we were more often slugging it out in clubs with genuinely scary rock bands, not writing pretty songs to compare to R.E.M.

GW: There was a time when you and R.E.M. were on equal footing, the two great hopes of bringing underground music aboveground. Have you reflected on that much?

WESTERBERG: Of course. I’ve had to mention them in every interview I’ve done since 1981. The problem is, they don’t have to mention us anymore. You’d think I would learn my lesson and never mention their name again. They simply don’t have to acknowledge us anymore. They won.

GW: Why have you not used another guitarist on either of your solo albums?

GW: Why have you not used another guitarist on either of your solo albums?

WESTERBERG: I never think that my songs need guitar embellishment. I tend to think of them as simple tunes which can pretty much be carried by the chord structure and vocal melody. If your interest is maintained by a little guitar or horn flavor, great, but I don’t really think that my songwriting generally calls for flashy guitar work. And if it’s not flashy, I can handle it.

GW: You use different tones to create a full guitar sound yourself. Do you utilize different amps to do that?

WESTERBERG: No. Years of performing have taught me to control things from the axe. I’ll just roll off the high end or play with the volume at two or three. I’m not an effects person and I don’t have an arsenal of amps at my disposal, but I am picky about my sound. I don’t like sustain and I don’t like a lot of compression. I prefer a sound that’s right in between dirty and clean and doesn’t have that 10-second sustain when you hit one chord. I’m pretty much lost when the tone gets over-saturated and there’s no distinguishing between one chord and the next. You need to be able to hear me change chords. But I just keep it simple—amp, guitar. Besides, I hate music stores—I never go into them.

GW: Why do you hate music stores so much?

WESTERBERG: They’re just jam packed with guys who don’t have it, guys who spend their lives learning how to play the instrument but don’t have anything that people want: no personality or life about them. I see a lot of bitterness in music stores and I always have. I remember trying to buy a saxophone at the band instrument store and even that place had a total loser vibe. The guy picks up the horn and blows this Coltrane-esque run with me, who can’t play at all, looking for help and getting really pissed. I was like, “Fuck you. I’ll go find one at a garage sale and teach myself.” And I did.

GW: Eventually sounds very organic and relatively raw, so why did it take you three years to record?

WESTERBERG: Most of the songs are essentially live—my parts and the main rhythm parts are live takes. That’s the case for “These Are The Days,” “Once Around The Weekend,” “Trumpet Clip,” “Love Untold” and probably a few others. But sometimes it takes a long time to get a really good first take.

GW: You began to record the album last spring in Atlanta with Brendan O’Brien, then pulled out after a few weeks and only three songs from those sessions ended up on the album. What happened?

WESTERBERG: When you don’t spend a lot of time overdubbing, what you’re really going for is a performance and sometimes you’ve just got to admit, “Hey, I’ve got the wrong mix of people. Maybe I should write some new songs and try it again in six months with someone else.” That’s just what needed to happen. It would not have been as good a record had I finished it all in Atlanta.

GW: Are there any specific songs that benefited from the change?

WESTERBERG: The prime example is “These Are The Days.” Brendan really wanted that song to be a ballad and I felt it had to be rerecorded with more of an uplifting lilt, and I think the results prove I was right. But, look, the sessions with Brendan weren’t a disaster by any means: “Love Untold” is the first single and whatever it took, we got one magic, live take. We thought we were going to make a great record, but it didn’t work out that way. We ended up with one great song and two really good songs. That’s not a bad two weeks.

The producer’s role is at times an unenviable one. If things aren’t going well, he has to make suggestions, but he doesn’t know what’s deep in me. He saw something that wasn’t working and he tried to make it work, but I knew that direction we were taking it was not right.

GW: And I suppose that one of your reasons for going solo was to be able to do things your way without having to run it by other people.

WESTERBERG: [pauses] That’s very astute of you. Sometimes I really miss not having a band because if a song needs tension, it’s hard to provide it by yourself. But I willingly give that up in order to be the final vote on everything I do because I think I know what the feel should be—and I’m the one who has to live with it forever.

GW: This may sound strange, but “Time Flies Tomorrow” has sort of an Allman Brothers vibe.

WESTERBERG: It’s not strange. You’re probably thinking of “Melissa.” I didn’t dodge it sounding like something else, but I thought it was more reminiscent of [The Rolling Stones'] “Moonlight Mile.” I think some of the best songs sound instantly familiar. When you choose to work in the arena of simple chords, what you are basically saying is, “This is a I-IV change. You’ve heard it in a million pop songs, but I’m going to give it to you again with my own lyrics.”

GW: You use several bassists on the album, including yourself. How do you decide when to bring someone in and when to play it yourself?

WESTERBERG: Every once in a while, I want an aggressive bass part, and I can’t do that, but if it’s a loping, folk-pop thing I’ll just do it. A lot of bass players frown on that style, but sometimes you’re better off when you don’t know a lot, and I only play the root note. To me, rock and roll is drums, rhythm guitar and vocals. Lead guitar and bass are almost superfluous if the drummer is great and the rhythm is tight. I’ll usually cut live with the drummer and if there’s a bass player there, I’ll have him take a crack at it. When I listen back, if the drums aren’t doing it for me, I usually blame the bassline and redo it, simplified, myself. The bass playing that I like is minimal, ever-so-slightly behind the beat, and played with the kick drum.

GW: Do you still consider yourself a punk at all?

WESTERBERG: Was I ever or will I ever not be? Somewhere in between lies the answer. I am a musician and an artist, which is something I couldn’t have said back then ’cause we would have been laughed at. We were anti-artists. We were punk rockers, but I think the connotations the word has these days are very predictable and silly. I would be more happy to say I’m a well-rounded adult. That’s much more dangerous than being a punk these days.

GW: Who were your primary guitar influences?

WESTERBERG: The usual suspects from the school of crash and burn guitar playing: Keith Richards, Johnny Ramone and Johnny Thunders. Everything sort of comes from those three, at least in terms of rhythm. Lead-wise I listened to a good deal of blues, anyone from Albert and B.B. King and Eric Clapton to Mick Taylor and Mick Ronson. Plus Neil Young—and Bob, who influenced me a lot.

GW: That may cover the hard rocking stuff, but there is another, very different side to your music as well—the ballads. Who were some of your main songwriting influences in that regard?

WESTERBERG: There’s someone I always think of, but hesitate to say and I’ll just say it: Burt Bacharach [composer of such pop hits as "Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head" and "Do You Know The Way to San Jose"]. My ear has always been pulled to piano chords, which I think is largely what set the Replacements apart; we were a garage band playing at extreme volume, yet I was playing things like sixths and major seventh chords, which immediately made people say, “Well, that’s the Beatles.” Yes, the Beatles used those chords, but so did every other pop songwriter. Top 40 pop radio of my youth was my songwriting guide.

GW: Were you scared to sing ballads when you first started writing them?

WESTERBERG: Yes. And to this day I’m never charged with courage when I write them and, especially, when I present them to the first person. I’m always a little sweaty palmed. I have learned that the ones I am most afraid for anyone to hear are usually the ones that will strike a chord with people. But the fear is real and true—those are also the ones someone will laugh at. You just can’t be afraid of sounding wimpy or of someone pointing a finger and laughing at you.

GW: Your songs tend to be very personal. Have you ever written a song that was just too personal to record?

WESTERBERG: Too shit! [laughs] “Too personal” could be a euphemism for too whiny, too maudlin or too self-centered. I think I’ve reached the point where I know when I cross the line into masturbation.

GW: Why have you never included lyric sheets on an album?

WESTERBERG: Two reasons: growing up, my favorite records never had the words in them, and whenever I see lyrics written out, I always think that a good song doesn’t necessarily make for good poetry. It’s the marriage of melody, lyrics and rhythm that makes a song. And that’s what I do. I don’t write poems.

GW: Do you hear your influence in other bands often?

WESTERBERG: Not often enough. I hear my influence in a whole lot of people who profess to never have heard us, which bothers me a little. It’s fine when people acknowledge where they got it. You’re welcome to anything—borrow, lift, steal it all, as long as you admit it, because I’ve always been honest about where I took things, whether it be Eric Carmen or Hüsker Dü.

GW: The Goo Goo Dolls have always sounded a lot like the Replacements and they had a hit with “Name,” which sounds like one of your outtakes.

WESTERBERG: What can I say? For seven years John Reznick had to talk about me. Now I have to talk about him. The Goo Goo Dolls obviously fall into the category of a band that listened a lot to the Replacements, learned from us and took from us, but have made no bones about it. So they have my blessing.

GW: Have you heard Wilco or Son Volt?

WESTERBERG: Ugh. No comment. I’m always mystified when I hear my own voice on the radio. I never know who it is and it’s really weird when I realize, “Oh my God, this is me.” Well, I’ve thought I heard myself a few times when it’s been them, and that makes me very uncomfortable. They’ll swear up and down that I’m full of shit and they never listened to us. I guess we listened to the same people growing up then.

GW: Legend has it that the Replacements stole your masters from the Twin/Tone offices and threw them into the mighty Mississippi. Is that true?

WESTERBERG: As many as we could carry. [laughs]. I think we took about five reels, and I don’t even know what they were. We thought we were taking outtakes, which we were convinced they were going to release because we had signed with Sire. We didn’t think it was fair for our outtakes to become a record.

GW: Another Replacements legend is that your first gig was at an alcoholic halfway-house. Is that apocryphal?

WESTERBERG: No. That was our first performance, though we didn’t play a note. We were physically ejected from the building for being drunk. All of this stuff that sounds like a bold-faced lie is the truth. The only myth I’ve ever heard was the thing about the vomit dripping off the ceiling in Memphis while we were recording Pleased To Meet Me. Someone made that up.

GW: Has your opinion on videos changed at all since you attacked them in “Seen Your Video” [Let It Be, Twin/Tone, 1984]?

WESTERBERG: I thought I was waving a flag saying, “This is real rock and roll and that isn’t.” I was probably masking my fear of the medium. I no longer fear making a video, but I honestly don’t like them. I never have and I never will. I like film and I understand that a filmmaker has a right to interpret and fulfill his vision, but not on my song. I have given the lyrics all the visual that is necessary. I want people to think of the time they met their girlfriend to this song, or had a fight, or went for a ride, not some guy with no teeth, and a midget dancing with a hot babe.

GW: Do you write on an acoustic?

WESTERBERG: I used to. More and more, I’m writing on piano, then adapting it to acoustic. The melodies are born on piano, then I just play the simpler, nut-position chords on the guitar. The piano helps me sing melodies that I wouldn’t come up with over a G and D chord. I hum up the melodies and adapt them to my basic three chords.

Of course, the rockers, like “You’ve Had It With You” I write on electric guitar. I just tune to an open chord and bang out the riff.

GW: You guys were always associated with Hüsker Dü, but did you ever identify with Prince as a local guy?

WESTERBERG: Sure. We experienced the same weather and a lot of the same things growing up. Minneapolis audiences are mighty reserved, and learning to command an audience in a place where people are notorious for being quiet will either make you a wallflower, quiet artist, or it will make you really boisterous, aggressive or flamboyant, which is what it did for both of us. I really think a lot of his flamboyance came from the suppression of the place that we live. It’s a cold place to live in more ways than one.

GW: A lot of people thought “World Class Fad” [14 Songs] was about Kurt Cobain.

WESTERBERG: I know for a fact that he did. I feel bad that he died, if that’s what you want to know. I feel real bad, because he was a major talent. But more than that, I feel happy that he was born and that he heard the shit that he did.

GW: Did you recognize things in his life and think that his path is one that you or someone on the Replacements could have followed?

WESTERBERG: Yeah. I think the eventual death of Bob illustrates that perfectly. That could have and probably would have happened a lot sooner if we had had a lot of success and become really popular before we developed any semblance of maturity. And he might not have been alone, either. Let’s leave it at that, please. We knew that what happened to Bob was gonna happen one day, which didn’t make it any less shocking or tragic.

GW: What do you think is your greatest strength as a guitarist?

WESTERBERG: My understanding of yet inability to play the blues. I approach my rock and roll or pop music the way someone else would approach blues. I try to keep it as bare, simple and real to life as possible. Because my true desire, my dream in life—which I have never before revealed—is to be the greatest blues guitar player in the world. There, I said it.

GW: I think your description of what you try to do on the guitar could apply to your songwriting as well.

WESTERBERG: Absolutely. A lot of people wouldn’t understand that. They’d say, “But you use more chords and sing songs that sound like the Monkees. That’s not the blues.” Well, that’s like saying the blues always have to be about waking up this morning and feeling bad. That’s not what makes for great blues. It’s the honesty is what it is.

And there’s another thing to be learned from the blues: once you realize that playing guitar is mainly about what kind of shirt and shoes you’re wearing, it all falls into place.

September 16, 2014

Happy Birthday B.B. King: An appreciation and personal history

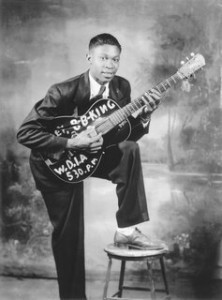

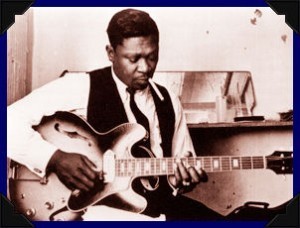

Photo by Kirk West – www.lesbrers.com

B.B. King turns 89 today. Happy birthday Mr. King.

Three years ago, I took my son Jacob, then 13, to see B at the Wellmont Theater in Montclair. I wanted Jacob to see him, and he had a truly memorable experience. When Jacob went up front to take a picture, he was standing right in front, when the great man said, “Hey there, little dude” into the mic, leading everyone to cheer. B.B. then flipped Jacob a guitar pick, which he had to get down and scramble to find on the floor, before returning to our seat with a huge smile.

At 86, B.B. was on something of a valedictory tour. The show was short and he did not play a lot of extended lines, but his voice sounded great, with a strong command of dynamics. His playing was a little shaky at times, and really magnificent at others. The band was excellent, and I really don’t think a single person there was anything other than happy. I feel lucky to have seen B.B. many times over the yeas and they’ve all been different.

The first time I saw B live was in college. He came to the Michigan Theatre and I interviewed him for a preview in the Michigan Daily. I was really excited. The show was just fair. The band was good and B.B. was a great showman and sang really well but he barely played. He ripped off no extended lines, which was a little frustrating. He would play a great lick, and then just stop and start shucking and jiving or let the other guitarist take over.

I thought, “This was cool to see but he’s not so great any more.” Then less than a year later, he was playing the Masonic Temple in Detroit with Albert King and Bobby “Blue” Bland. I went with a few friends. We were in our usual scrubby T-shirts and jeans. The rest of the crowd was almost all older black folk dressed like they were going to church.

All three performers were excellent, if brief. B.B. was totally different than he had been the first time I saw him. He put on a radically different show than I had seen in Ann Arbor. He was charming, funny, but less hammy and he ripped on guitar. It was so cool.

After the show, we were blocked into our parking space. I saw three old ladies get into the car in front of us and start up and I patiently waited for them to leave. They did n ot do so. I waited some more. Nothing. Not wanting to be rude and honk, I got out and walked up to the window and tapped on it. It rolled down and the three old biddies in church hats were sitting pressed together in the front seat of this Olds 88 passing a big doobie around. The driver rolled down the window and a big cloud of smoke came out, Cheech and Chong style, and I said, “Excuse me, I’m stuck behind you. Could you please pull forward?”

ot do so. I waited some more. Nothing. Not wanting to be rude and honk, I got out and walked up to the window and tapped on it. It rolled down and the three old biddies in church hats were sitting pressed together in the front seat of this Olds 88 passing a big doobie around. The driver rolled down the window and a big cloud of smoke came out, Cheech and Chong style, and I said, “Excuse me, I’m stuck behind you. Could you please pull forward?”

“Sure. Sorry, baby.” Giggles all around.

I saw B.B. again in front of a white crowd a year or so later and he was pretty lame. I thought, “I’m not seeing him again.” About a year later, my friend Skirboll had tickets to B.B. at Pittsburgh’s Heinz Hall and really wanted me to go with him. Ok, fine. I went, mostly to have a good hang with Skirbs, who was really excited to see B.B. Heinz Hall is the home of the Pittsburgh Symphony and B.B. rocked. He was again totally different than the first time I had seen him. He played extended lines, he was surprising and passionate in his playing and not hamming it up as much. It was really cool.

That had to be 20 years ago, so he was at least 65, and he was clearly undergoing a renaissance. It was shortly after he recorded “When Love Comes to Town” with U2 and I think that really had something to do with re-inspiring him, by again bringing him a new, younger crowd.

Since then, I’ve seen him many more times in different settings and while always a little different, and while he began mostly sitting down about a decade ago, the playing has mostly gotten more and more inspired. I have seen him fiddle with distortion, play jazz, do cool comping behind his pianist and guitarists. It is really astounding how he kept pushing at that stage of the game. That era seems to be over, but the new one, of him taking a victory lap of the nation on his endless tour, is kind of cool as well., though thre years have passed and I’ve heard some pretty scary reports.

In any case, definitely worth taking a moment to apy tribute to why B.B. matters in the first place.

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

I wrote the following almost 20 years ago when B.B. debuted a column with Guitar World. This was the intro to the first one.

Life of Riley

A brief history of the King of the Blues, Riley B. King, aka B.B.

By Alan Paul

He’s known as the King of the Blues, and one reason may be that B.B. King remains the only black blues artist to have successfully penetrated the thick walls of American popular culture. He is the only one to step inside from the commercial cold that has long been the bluesman’s fate, to receive presidential citations and honorary degrees, to star in commercials for everything from McDonald’s to Northwest Airlines and to become an international ambassador of both good music and good vibes. He has become so omnipresent that it’s easy to forget why he’s so revered: he is the man who fundamentally changed the way the electric guitar is played.

He’s known as the King of the Blues, and one reason may be that B.B. King remains the only black blues artist to have successfully penetrated the thick walls of American popular culture. He is the only one to step inside from the commercial cold that has long been the bluesman’s fate, to receive presidential citations and honorary degrees, to star in commercials for everything from McDonald’s to Northwest Airlines and to become an international ambassador of both good music and good vibes. He has become so omnipresent that it’s easy to forget why he’s so revered: he is the man who fundamentally changed the way the electric guitar is played.

“None of us would be here today if it weren’t for B.B.,” says Buddy Guy. “He changed the way all of us squeeze the strings.” Guy should know; his pumped-up, wildly frenetic guitar style owes its heart and soul to King’s far more sedate approach. It is safe to say, in fact, that every blues-based electric guitarist on the planet owes a huge debt to B.B. King, whether they know it or not.

King took single-string electric lead guitar playing, pioneered by jazz pioneer Charlie Christian and sophisticated Texan bluesman T-Bone Walker, added elements of acoustic blues greats Lonnie Johnson and Blind Lemon Jefferson and the fiery gypsy jazz of Django Reinhardt and emerged with the highly personalized B.B. King sound: stinging finger vibrato, economical, vocal-like phrasing, and heavenly bending. This style strongly influenced every electric blues guitarist to follow, including Guy, Albert King, Freddie King and Otis Rush. These players, in turn, inspired countless rock guitarists, notably Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan. The rest, as they say, is history.

A good place to experience King’s groundbreaking style is The Best Of B.B. King, Volume One (Flair/Virgin), an essential collection which includes his original versions of standard-bearers like “Three O’Clock Blues,” “You Upset Me Baby” and “Five Long Years.” On these tracks, recorded in the 50s, the core elements of B.B.’s sound are already developed, with his distinctive single-note leads playing call-and-response with his powerful, gospel-heavy voice and a punchy, sophisticated horn section.

Ironically, the most signature feature of King’s playing—that remarkable, utterly distinct vibrato—came about because of a personal failure. As a young guitarist, Riley King could not master slide guitar, the style of choice in his native Mississippi Delta. Instead, he learned to mimic the whining, lyrical slide tone of Delta masters like his uncle Bukka White and Robert Nighthawk by using his hands alone – specifically by developing his vibrato, which he achieved by shaking his finger perpendicular to the neck.

“I always loved the sound of slide players,” King explains. “I’ve never been able to play slide myself, but I found that when I trill my hand I can fool my ears into thinking it’s a person using a slide.”

King augments his beautiful vibrato with a remarkably lyrical sense of phrasing and an innate ability to use each note to maximum effect—of not overplaying.

“When you’re a soloist you don’t play a note just because you can find one,” he says, matter-of-factly. “You do it because it makes sense. Every note is important. If it can be done well with less, then do that. Another reason that I don’t play a lot of notes is I feel that I’m still singing when I play. When I’m playing a solo, I hear me singing through the guitar.”

B.B.’s vocal-like guitar playing is part and parcel of his rare ability to communicate intimately with an audience, to make any size auditorium seem like a small room and every listener feel as if he’s playing just for them. It’s a skill that draws the crowd in, making them feel like a part of the proceedings. This powerful rapport is perfectly captured on Live At The Regal (MCA), a document of a 1964 performance which is considered by many to be not only his finest recording, but the greatest album in all modern blues. This treasure-trove of sophisticated-yet-down-home music includes such staples as “It’s My Own Fault,” “Every Day I Have The Blues” and “Sweet Little Angel.”

By all means buy this album, but don’t forget that the real way to experience B.B.’s power is to go see the man for yourself. You won’t be disappointed. Perhaps the most impressive thing about B.B. King is that he continues to push himself hard, to try new things and stretch out his playing. This can be heard on fine albums like the star-studded Blues Summit (1993) and his last new release, the excellent Blues on the Bayou (1997), but the stage remains B.B.’s real pulpit. He can still swoop up entire audiences into the palm of his hand and hold them rapt with a single mellifluous run. Most remarkably, at age 74, after over 50 years in the business, he never seems to get bored, never takes anything for granted or rests on his laurels for even one night. How many other legends can make the same claim? Long live the King.

September 4, 2014

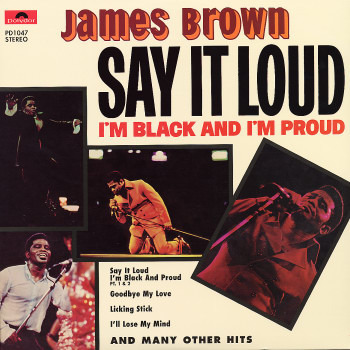

The time I interviewed James Brown about Say It Loud and I’m Black and I’m Proud

In 1999, Guitar World devoted an entire issue to the 30th anniversary of 1969, which we proclaimed the greatest year in rock. I wrote the histories of several landmark albums, including James Brown’s Say It Loud (I’m Black And I’m Proud). The best part of the entire project by a long shot was interviewing the great man himself. I am still searching for the interview tape, but the whole thing was a classic.

This seemed like an excellent time to revisit, what with the current run of the great biopic Get On Up.

Note how entirely ungracious he was towards Jimmy Nolen, his longtime collaborator and the man who really wrote the book on funk guitar. Brutal. I was trying to spoonfeed him questions that would lead to him proclaiming Nolen’s greatness, but he was having none of it.

*

Random photo of Kirk West and the Godfather.

When James Brown released the single “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” in late ‘68, he was an artist on a roll, with a huge and expanding audience, both black and white, and a steady diet of hits on both the pop and r&b charts. But “Say It Loud,” interpreted by many white listeners as an angry rebuff, was to be his final pop hit.

Today, Brown says that anyone who viewed the song as an angry anthem was way off base. “I was trying to do two things,” says Brown, who recently released I’m Back (Private Music). “One, give the power structure –which in America means the white power structure – a way to understand how we felt, and know that we had people who could do things and just wanted a fair shake. Two, I wanted young black kids to wake up and realize that they should be proud of who they were, get an education and try to make something of themselves. Proud and bad are too different things. I never wanted to separate. My thing was to let the pride be there, and to let people get into the skin of a black man and realize that he only wants to be recognized for the contributions that he has made.

“I was just telling it like it is. Would you rather have someone tell you how they’re feeling to your face, or wait till you turn around and whisper their anger behind your back? You got to swing for the fences every time you’re at bat; you owe it to your children and grandchildren. That’s what I was doing, and I’ve always been about building, not destroying. I was there when Dr. King was assassinated, telling everyone to cool out, trying to remind everyone that you don’t want to destroy your country. You want to build it.”

“I was just telling it like it is. Would you rather have someone tell you how they’re feeling to your face, or wait till you turn around and whisper their anger behind your back? You got to swing for the fences every time you’re at bat; you owe it to your children and grandchildren. That’s what I was doing, and I’ve always been about building, not destroying. I was there when Dr. King was assassinated, telling everyone to cool out, trying to remind everyone that you don’t want to destroy your country. You want to build it.”

Nonetheless, notes Brown expert Harry Weinger, “That record lost him a big audience. From ‘65 to ‘68, he was extremely popular, with his audience getting wider and wider. Then he did this album and lost his white audience, and never had another top 10 single.”

What all these listeners were missing is the fact that whatever his politics, Brown’s music was just getting leaner and meaner, and ever funkier. The album Say It Loud, which was really a collection of singles recorded throughout ’68, also included the impossibly taught “Licking Stick” and the organ-driven instrumental “Shades of Brown.”

“Hey, that was just continuing what I started a few years back when I changed the music from being on the 2 and 4, where it had always been to the 1 and changing the emphasis from the downbeat to the upbeat,” Brown says. “That’s what created funk music – gospel and jazz mixed together by James Brown with a little help from God. And I just kept doing it and innovating it, right on through ‘Say It Loud’ and further.”

The single and most of the album also feature the distinctive sound of Brown’s backing band, the JB’s featuring guitarist Jimmy Nolen, generally credited as a major funk innovator. Brown says Nolen was great, all right, but he really wasn’t all that original.

“Sometimes ignorance is bliss,” Brown says. “Jimmy Nolen was a man who could play anything I wanted him to play and didn’t know enough to play anything but what I wanted. And that’s what made him great on ‘Say It Loud’ and everything else.”

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

August 26, 2014

RIP Brian Farmer, another good man gone too soon.

This photo by Michael Weintrob says it all. Farmer working so Warren could do his thing without ever thinking twice about anything gear related.

Warren Haynes’ longtime and much beloved guitar tech Brian Farmer died Sunday August 24, at his home near Nashville. Farmer died peacefully in his sleep. He was 53.

“He was a close friend, a devoted worker, and a lover of life,” says Haynes. “We traveled around the world together and shared many experiences-mostly while laughing. He will be missed by a huge circle of friends and family.”

Brian Farmer was extraordinarily dedicated to his craft, to the world of guitars and amps, to Warren and all his projects – and to the music itself. People like Brian keep the wheels turning and the gears greased and the guitars in tune. The shows don’t happen without them – and no one did any of this better, with more dedication, heart and soul than Farmer.

Farmer began working for Gov’t Mule in 1998, brought to the band by his old friend, bassist Allen Woody, who died almost exactly 14 years earlier. Prior to joining the Mule crew, Farmer worked for Johnny Cash for eight years before the Man in Black retired from touring. Farmer was exceedingly proud of his close relationship with Johnny and June Carter Cash.

“When Johnny retired, I ran into Allen and said, ‘You need to hire me, you need to hire me,’ Farmer told Hittin the Note magazine.

Months later, Gov’t Mule needed a guitar tech and Woody called his old friend. In the subsequent years, Farmer became an indispensable part of the operation, teching Warren Haynes’ guitars and also serving as the band’s equipment manager and stage manager.

Farmer has been by Haynes’ side for every gig the busy guitarist has played since 1998 – with Gov’t Mule, the Allman Brothers Band, the Warren Haynes Band, the Dead, Phil and Friends and others.

Farmer and Haynes developed an extremely close working relationship.

“We have looks that we give each other,” Farmer told Hittin the Note. “An eyebrow, a flick of the wrist… a shrug of his shoulders …I’ve learned to listen for things. I can tell sometimes when he’s close to breaking a string. With the Mule, I sometimes come out to adjust his amplifier before during and after songs.”

“He was one of a kind,” says Haynes. “He lived and breathed his job. He knew a lot more about guitars and gear than I did so I could trust him to keep things working in a technical manner so I could concentrate on the music.”

Farmer at Wake Up With Warren, Peach Fest 2014 – Sunday, August 17. Photo by Derek McCabe.

Says Allman Brothers Band manager Bert Holman, ”Brian was a very dedicated, very loyal, very skilled technician. He was from the old school and would help anybody and everybody do their job. If something of Derek or Gregg’s blew up, he’d be the first guy to grab a flashlight or tool and run across the stage because he was a team player. His standard line to any request was, ‘Just tell me what you need.’ Brian always had your back. He was kind to the fans and tried to give them as much time as he could without taking his eyes off the ball, which he never, ever did.”

Farmer also had a very close relationship with the Gibson Custom Shop, working with them on all of Haynes’ custom guitars.

“Brian was more than a visitor to Gibson Custom,” says Rick Gembar, Gibson Senior Vice President and General Manager of the Custom Division. “We were blessed to get to know him over the years as he came and went on behalf of Warren. During those years, he built relationships with everyone, from the front desk to the craftspeople, to me personally. He was a friend, well respected as a technician and genuinely admired for his kindness as much as for his tireless work ethic and attention to detail. Seeing him come through the door was always a welcome sight to the people here.

On behalf of everyone here at Gibson Custom, I send our deepest condolences to his family, Warren, Brian’s friends and all others that he touched during his time.”

Farmer’s death was greeted with shock and grief across the internet by fans and musicians alike. It is hard to imagine many other rock and roll road crew members who were more respected and beloved. Among those expressing their sorrow and respect on Twitter were Phil Lesh – “Fare thee well, Farmer – I love you more than can words can tell” and Derek Trucks.

The latter summed things up beautifully in a series of #ThankYouFarmer tweets: “People like Brian Farmer are the backbone of all live music. Without the hard work of folks like Farmer we’d be lost.”

August 23, 2014

An interview with John Fogerty

I interviewed John Fogerty last year for the Wall Street Journal in advance of three shows he played at the Beacon. We spoke a lot longer than I could come close to capturing in that piece. A more extensive Q&A ran in Hittin the Note magazine. Here it is .

I interviewed John Fogerty last year for the Wall Street Journal in advance of three shows he played at the Beacon. We spoke a lot longer than I could come close to capturing in that piece. A more extensive Q&A ran in Hittin the Note magazine. Here it is .

••

It’s a bit overwhelming to see John Fogerty in concert and realize just how many hits and truly classic tunes the singer/songwriter/ guitarist wrote for Creedence Clearwater Revival. “Proud Mary,” “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” “Fortunate Son” and “Born on the Bayou” are just the start of what feels like an endless stream. The group released five hit-laden albums in three incredibly productive years, before sputtering, then breaking up acrimoniously in 1972.

Fogerty doesn’t jam per se; he recreates the song’s original versions, with both his voice and guitar sounding remarkably similar 40-plus years later.

Just hearing Fogerty perform these great tunes is a treat; for 25 years he refused to do so in public, embittered by lawsuits and the fact that he no longer owned the rights to his work. He resumed singing the songs in 1997 and on his recent tour, he played the albums Bayou Country and Cosmo’s Factory.

Fogerty’s most recent release was Wrote A Song For Everyone, featuring him re-creating some of CCR’s many hits with a variety of guest artists, from Jennifer Hudson to Bob Seger, Brad Paisley to Kid Rock. We spoke on the phone as his tour bus rolled through Virginia.

AP: You avoided playing the Creedence songs because you did not own the publishing and were involved in a lot of rights and suits over them. Has anything changed in your situation with those tunes?

FOGERTY: Not really. I don’t own the songs. At this point Concord Records, which bought Fantasy Records, own these songs. I do feel that I’m getting much fairer payment than I did while Fantasy was owned by Saul Zaentz, so that’s an improvement. I sure wish I had some better advice when I was quite young, but by the time I actually figured out what was up, it was too late. We had already signed all the contracts. Certainly at that time in that place, no one was going to do the right thing. Sometimes I look back at that and in the long run, I think they were incredibly shortsighted and maybe even stupid to have someone with that much talent and productivity under your wing and then alienate him in such a way that he never wanted to walk back in the building again, thereby losing whatever great music might have been made over the next 30 or 40 years. I think they just abandoned what was really working for our group. They insisted on going far away from that and basically destroyed the product.

AP: I just wrote a book on the Allman Brothers Band and as you probably know, they had a very similar deal with Capricorn Records, who had their label, management and publishing in one place.

FOGERTY: Yes, sadly we were not that unique in these regards. I’d really like to read that book, by the way. I am, of course, a big fan of the Allmans, one of the great bands

AP: You went about 25 years refusing to play your own CCR songs. Do you feel like you’ve reclaimed them, and a part of yourself and your own heritage?

FOGERTY: Yes, very much so. I started playing them again in 1997 on my Blue Moon Swamp tour. By then I had well made up my mind to start playing them again and was really ready to go.

It all came about back in 1990. I had taken a few trips to Mississippi. I thought I was figuring out the blues legends’ family trees, visiting the important sites of the great guys I grew up with: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, and so many other great people.

I was at the purported grave of Robert Johnson, sitting in the very hot, humid Mississippi sun and communing with him. Robert was an unlikely pop star at that moment, with a hit album. Columbia had released a box set of his songs and it had become a big hit, with a lot of literature, and the one photo of him that was known at that time. I was having a conversation with myself, wondering who owns Robert’s songs? And I got this image in my head of a shyster lawyer with a big cigar sitting in a tall building making all this money off the man’s work.