Alan Paul's Blog, page 33

August 5, 2014

One Way Out excerpt: The recording of At Fillmore East

In honor of the release of the  expanded The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings, I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

expanded The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings, I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is a partial, very abridged version of Chapter 8. To read the full story of the making of At Fillmore East, pick up a copy of One Way Out at Amazon, Hittin the Note, or your favorite retail establishment.

“Moving and exhaustive….”

-The New York Times Book Review

*

Chapter 8.

LIVE ALIVE

Though their first two releases had caused barely a ripple in the marketplace, the band was drawing raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with superior musical precision and a deep grounding in the blues. A live album was the obvious solution. To cut the record, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights — March 11, 12 and 13, 1971. They were paid $1250 per show.

The Allman Brothers Band had made their Fillmore East debut December 26-28, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat and Tears for three night. Promoter Bill Graham loved the band and promised them that he would have them back soon and often, paired with more appropriate acts, and he lived up to this vow.

On January 15-18, 1970, the ABB opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. They were back in New York on February 11 for three nights with the Grateful Dead. These shows were crucial in establishing the band and exposing them to a wider, sympathetic audience on both coasts.

TRUCKS: You can’t put in words what those early Fillmore shows meant to us. The Fillmore West helped us get established in San Fran and it was cool – especially those shows with B.B. and Buddy – but the Fillmore East was it for us; the launching pad for everything that happened.

ALLMAN: We realized that we got a better sound live and that we were a live band. We were not intentionally trying to buck the system, but keeping each song down to 3:14 just didn’t work for us. We were going to do what the hell we were going to do and that was to experiment on and offstage. And we realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off; we need to make a live album.

BETTS: There was no question about where to record a concert. New York crowds have always been great, but what made the Fillmore a special place was Bill Graham. He was the best promoter rock has ever had and you could feel his influence in every single little thing at the Fillmore. It was just special. The bands felt it and the crowd felt it and it lit all of us up. The Fillmore was the high-octane gig to play in New York — or anywhere, really.

Bill Graham introducing the ABB. Photo by Sidney Smith. All rights reserved.

ALLMAN: That was the place to record and we knew it. It was a great sounding room with a great crowd, but what really made it special was the guy who ran it. Bill Graham called a spade a spade and not necessarily in a loving way. Mr. Graham was a stern man, the most tell-it-like-it-is person I have ever met and at first it was off-putting. But he was the fairest person, too, and after knowing him for while, you realized that this guy, unlike most of the other fuckers out there, was on the straight and narrow.

PERKINS: The Fillmores were so professionally run, compared to anything else at the time. And he would gamble on acts, bringing in jazz and blues and the Trinidad/Tripoli String Band – and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered.

DOWD: I got off a plane from Africa, where I had been working on the Soul To Soul movie [capturing a huge r&b, jazz and rock concert held in Ghana], and called Atlantic to let them know I was back and Jerry Wexler said, “Thank God; we’re recording the Allman Brothers live and the truck is already booked,” so I stayed up in New York for a few days longer than I had planned.

It was a good truck, with a 16-track machine and a great, tough-as-nails staff who took care of business. They were all set to go. When I got there, I gave them a couple of suggestions and clued them in as to what expect and how to employ the 16 tracks, because we had two drummers and two lead guitar players, which was unusual, and it took some foresight to properly capture the dynamics.

Dowd was thrilled with what he was hearing until the band unexpectedly brought out sax player Rudolph “Juicy” Carter and another horn player, as well as harmonica player Thom Doucette, a frequent guest who had played on Idlewild South.

DOWD: We were going along beautifully until the fourth or fifth number when one chap looked up and asked, “What do we do with the horns?” I laughed and said, “Don’t be a smart ass,” thinking he was joking, but three horn players had walked on stage. I was just hoping we could isolate them, so we could wipe them and use the songs, but they started playing and the horns were leaking all over everything, rendering the songs unusable.

JAIMOE: Dowd started flipping out when he heard the horns, but that’s something that could have worked. There’s no way that it would have ruined anything that was going on. It wasn’t distracting anyone, and it was so powerful.

Photo by Sidney Smith – Tulane U. homecoming, 1970. All rights reserved.

BETTS: Dowd was going nuts, but we were just having fun and everyone was enjoying it. We didn’t change our approach because we were recording. We never hired any of those guys. They’d just show up and sit in, and we all dug it.

PERKINS: The horn players would pop up and just sit in for a few songs. Those guys were friends of Jaimoe’s – we just knew them as Tic and Juicy and everyone liked their playing. Nothing was rehearsed with them. They’d just get up and play. Them showing up at those Fillmore gigs was a surprise to me and I didn’t think it was a good idea.

JAIMOE: Tic was a tenor player, Juicy played baritone and soprano - sometimes together, at the same time – and there was an alto player we called Fats, who was not at the Fillmore and didn’t come around as much. We had played together in Percy Sledge’s band and I knew them from Charlotte, NC. Good guys and good musicians.

PERKINS: They often had some heroin with them and were welcomed for that as well.

JAIMOE: I don’t know about that; if they showed up with a little something, it was probably because Duane or someone asked them to do so.

DOUCETTE: The plan was to bring on the horns full time. Duane would have liked to have 16 pieces. Duane had six different projects that he wanted to do and he just thought he could do it all at once on the same bandstand.

DOWD: I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, “The horns have to go!” and he went, “But they’re right on, man.” And I said, “Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.” He asked if the harp could stick around and I said, “Sure,” because I knew it could be contained and wiped out if necessary.

PERKINS: Doucette had played with the band a lot so he was a lot more cohesive with what they were doing. Duane loved those guys, but he would also listen to reason and I don’t think he put up any fight with Dowd.

DOWD: Every night after the show we would just grab some beers and sandwiches and head up to the Atlantic studios to go through the show. That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again. They would craft the setlist based on what we still needed to capture.

BETTS: You have to listen to it being played back to get a sense of whether or not it came together and we loved having that opportunity. We just thought, “Hey this is cool… I didn’t know I did that… That sounds pretty neat.” We were just enjoying ourselves and the opportunity to listen to our performances. We didn’t do a lot of that board tape stuff and we weren’t real hung up on the recording industry anyhow. We just played and if they wanted to record it they could. We were young and headstrong: “We’re gonna play. You do what you want.”

We just felt like we could play all night and sometimes we did. We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on there. All we did was edit some of the harmonica out, where there was a solo that maybe didn’t fit. It wasn’t doctored up, with guitar solos and singing redone in the studio, as on so many live albums. Everything you hear there is how we played it. We weren’t puzzled about what we were playing. We were a rock band that loved jazz and blues. We really loved the Dead, Santana, the Airplane, Mike Finnigan, and all the blues and jazz greats.

TRUCKS: We were listening to people like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and emulating them and trying to add that level of sophistication to our music – to add jazz and improvisation to blues, rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

DOWD: The Fillmore album captured the band in all their glory. The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove. Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East. Here was a rock ’n’ roll band playing blues in the jazz vernacular. And they tore the place up.

BETTS: There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album: that was a hell of a band and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like. I think it’s one of the greatest musical projects that’s ever been done in any genre. It’s an absolutely honest representation of our band and of the times.

JAIMOE: Fillmore was both a particularly great performance and a typical night. That’s what we did!

ALLMAN: You want to come out and get the audience in the palm of your hand right away: “1-2-3-4, bang! I gotcha!” That’s what you gotta do. You can’t be namby-pamby; you can’t be milquetoast with the audience.

WALDEN: Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album. Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing was what they were all about, not recording, that a phonograph record was confining to a group like this.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

July 31, 2014

That infamous interview with Duane Allman

Photo by Sidney Smith

On December 3, 1970, Duane Allman sat for an infamous interview with Dave Herman of New York’s WABC.

Why was it infamous? Well, he was pretty hopped up and he said some crazy stuff, and some not-so-nice things about being a husband and father.

But it’s fascinating thing for fans and biographers alike. Have a listen…

One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band includes a Neal Preston from the interview.

July 24, 2014

Jaimoe and Junior Mack – an interview

The interview below originally ran on Guitarworld.com and WSJ.com’s Speakeasy blog – I combined two stories into one here. Over the ensuing two-plus years I have only gained more respect for Jaimoe’s Jassz Band and for Junior Mack, whom i have gotten to know quite well. And I have developed a much deeper relationship with Jaimoe. This represents one of my first in-depth conversations with him. there were many more to come in the writing of One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

*

Photo by Kirk West

Two thousand eleven was a banner year for solo releases by members of the Allman Brothers Band.

Gregg Allman’s Low Country Blues, Warren Haynes’ Man In Motionand Tedeschi Trucks Band’s Revelator were all nominated for the Best Blues Album Grammy Award. ( Revelator ended up winning.)

But the fourth and final release is the sleeper pick: Renaissance Man by founding Allman Brothers drummer Jaimoe and his Jasssz Band.

Released December 17, 2011, by lil’Johnieboy Records to less attention than any of his bandmates’ efforts received, Renaissance Manis a diverse, eclectic and thoroughly listenable album. Jaimoe is the band’s founder and heart, and the group features a septet of swinging, in-the-pocket players, including a great three-man horn section.

But what makes it all work is Junior Mack’s revelatory singing and guitar work. A New Jersey native and longtime staple of the New York blues world, Mack reveals wide ranging talent on Renaissance Man, with several memorable originals that span the blues, rock and jazz worlds. Mack also helps the band make the blues classic “Leaving Trunk” their own, turns in a moving version of the soul classic “Rainy Night in Georgia” and re-imagines the Allmans’ “Melissa” as a bossa nova.

We caught up with Mack and Jaimoe on the phone.

Jaimoe, the Allman Brothers Band pioneered the use of two drummers in rock. After so many years as part of a team with Butch Trucks, was it difficult to adjust to being the sole drummer in your own band?

JAIMOE: It took a little time. I’m glad I have the chance to do both. I play percussion on the drum set; that’s been my role in the Allman Brothers. Butch and I developed our style naturally and we complement each other and create a bigger, more interesting sound. A lot of drummers playing together play the exact same thing, which is ridiculous. That’s like having four guys singing in unison, instead of harmony, which makes for a much bigger, more interesting sound. You have to listen, find a space and add something. Some drummers just aren’t that musical, I guess.

Over the years, I stored up a lot of stuff in my head that I couldn’t use and now I can. If you listen to great musicians and try to analyze the difference between, say [saxophonists] Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane or [drummers] Max Roach and Tony Williams, you have to look beyond the notes; what made them great is their personalities. You can’t copy that. Drumming is more than keeping time and I’ve always been of the mindset of whatever you do, just do what you do and people will take notice.

Junior Mack

Who came up with the bossa nova arrangement of the Allman Brothers classic “Melissa”?

JUNIOR: That was me, and it was the kind of discovery that’s a happy accident. I was playing a private gig for the CEO of Alcoa with my solo band and I found out he was from Brazil and at the last minute they told me the band should play as much Brazilian music as possible – except I really didn’t know any. I started thinking of songs that could adapt to a bossa nova beat and I thought of “Melissa.” We tried it and I thought it worked beautifully. When I played it for Jaimoe, he loved it and we immediately added it to the set.

Junior, how big of an influence were the Allman Brothers on you?

JUNIOR: Very big. I have always loved their music and so meeting and playing with Jaimoe was a thrill and continues to be so. And, of course, it also helped provide a group of hardcore fans who were ready to listen to us and have been very supportive. The Allman Bros connection has helped tremendously. It’s been a great experience all the way. I grew up listening to Jaimoe and the Allman Bros as a kid, so there’s not too much more I can ask for.

All that being the case, was it intimidating for you to start playing with Jaimoe?

JUNIOR: It was a little intimidating but it came mostly from the seasoned cats that were also on the bandstand. I’m a self-taught guy. I didn’t go to school for music.. I don’t really know how to write or read music, so the intimidation came from playing with guys who are really stellar musicians like [saxophonists] Kris Jensen and Paul Lieberman and [trumpeter] Reggie Pittman and trying to relay my songs and ideas to them. These guys could communicate a little better than I could on a musical level.

JAIMOE: Junior is on everyone else’s level; he just didn’t realize it right away. Junior played a lot of blues for a lot of years and that’s how people think of him, but it’s not all they can do. He not only plays all diff styles, but he writes all different ways. I would say he is more of a composer because of the way he writes and the way he plays; it’s never random.

JAIMOE: Junior is on everyone else’s level; he just didn’t realize it right away. Junior played a lot of blues for a lot of years and that’s how people think of him, but it’s not all they can do. He not only plays all diff styles, but he writes all different ways. I would say he is more of a composer because of the way he writes and the way he plays; it’s never random.

JUNIOR: I’m rooted in the blues, so that’s in any music I play, sing or write, but I don’t really break it down. I just play and try to play what’s right for the song.

Despite the name and a three-man horn section, the Jasssz Band isn’t really a jazz band.

JAIMOE: You can call it more than ways than one. We have some jazz in our blues, some blues in our jazz and some rock in all of it. We do everything but hillbilly music. Maybe we should learn a Hank Williams song.

Junior played a lot of blues for a lot of years and that’s how people in the New York area think of him, but it’s not all he can do. When I grew up, everyone played baseball, basketball and football and that was normal. Same thing. He says that he was intimidated when he first started playing with us guys. Well, he was on the same level but didn’t realize it, but that’s okay; insecurity is the eye of the tiger!

Your CD is the sleeper pick from a great crop of Allman Brothers solo releases. You’ve been hidden behind the drums all these years….

JAIMOE: Thanks. That was always in the back of my head. You know, Ringo Starr made a couple of great solo albums after the Beatles broke up and no one expected that either!

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

July 18, 2014

Thank you Johnny Winter for what you did for Muddy Waters and much more…

Johnny Winter, Park West, Chicago, 1978. FOTO BY KIRK WEST

Six Strings Down. RIP Johnny

John Dawson Winter III, February 23, 1944 – July 16, 2014

A couple of years ago, my good friend and Guitar World colleague Andy Aledort wrote this great, harrowing piece for GW that includes some details about the albino guitarist’s 1994 brush with death. Andy knew Johnny really well, musically and personally and really goes deep in this story, which is highly recommended.

Guitar World also posted this fine obituary.

But I think that one aspect of Winter’s career that was actually a bit underplayed in all the obituaries I read and heard was his fabulous work resurrecting Muddy Waters’ career. Johnny played on and produced Muddy’s last four albums, starting with the great Hard Again. The title came about because during the sessions, Muddy apparently said something like, “This is so much fun it’s making my pee pee hard again.”

Muddy earned three Grammies for those four albums and they were the financial and commeercial highlights of his career. Johnny Winter allowed an American icon to go out on top, a feat that should not be forgotten or underestimated. ”I wanted to get him to sound the way he did in Mississippi,” Winter told the Wall Street Journal writer Marc Myers in a recent story.

The photos here are by my pal Kirk West (who was also the photo editor and chief photographer for One Way Out.)

Johnny Winter, Bob Margolin, Muddy Waters, Park West, Chicago, 1978. FOTO BY KIRK WEST

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

July 15, 2014

From the archives: Derek Trucks, Family Man

Derek, Beacon, 2014. Photo by Derek McCabe

I moved back from Beijing just before New Year’s 2009 and was a bit adrift after a tremendous 3.5 year run there. I had left an award-winning column, an award-winning band and an exciting life I loved. I was sitting in an empty drafty house in frigid New Jersey and wondering what was next.

Though still technically a Senior Writer for Guitar World, I hadn’t been doing much with all these other ventures and living in china and all…then the editors called and asked if I would like to interview Derek Trucks about his new album Already Free. Well, of course I would…

What follows is the story that got me back in the game. Within weeks I was working ont he 40th anniverary of the Allman Brothers cover story that would become the basis for One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

Originally published in Guitar World, May 2009

Derek Trucks is all grown up and glowing with confidence on Already Free, a new album recorded at home with his wife Susan Tedeschi and an extended family of friends.

Derek Trucks is not a kid. First impressions can be hard to shake, and Trucks has been in the public eye since he was a preteen prodigy with a freaky ability to channel Duane Allman’s slide sound. But it’s time to abandon any notions that he is still a youngster. Trucks is now a 29-year-old father of two married to blues singer Susan Tedeschi and a 10-year veteran of the Allman Brothers Band who also put in a year touring the world with Eric Clapton, in 2006. And if all that isn’t proof enough, now there’s the Derek Trucks Band’s Already Free (Legacy), his confident new effort.

The sixth DTB studio album is the first Trucks produced himself. It is also the first to feature a cohesive sound all the way through, incorporating the band’s diverse influences—jazz, blues, gospel, rock and Indian—into one groove-based package. With nothing left to prove, Trucks takes a more subdued approach to guitar playing than in the past, but he is ever more impressive, with glistening slide lines that snake through the music to underpin everything.

The confidence and unique tonal control at the core of Trucks’ style have only deepened. He is a master of the microtonal bends that are at the heart of both sacred steel gospel (popularized by Robert Randolph) and Indian classical music, both of which he has studied closely. No guitarist creates more sound, tension and feeling from a single note.

Trucks’ longtime touring group is at the album’s core, supplemented by a host of other musicians, notably Tedeschi and Doyle Bramhall II, his fellow guitarist from the Eric Clapton tour, who sings, plays on and co-produced three tunes.

The album was recorded at Trucks’ new home studio in Jacksonville, Florida, which he says was integral to the final product.

“It was a much more relaxed process, lending us freedom to try different things,” he says. “There were no time or money constraints. We could call up friends who are great musicians and ask them to come lay down tracks and just see what happened. We were just hanging out writing and recording music.”

GUITAR WORLD In this digital era, why did you decide to build a full-on home studio?

GUITAR WORLD In this digital era, why did you decide to build a full-on home studio?

DEREK TRUCKS The whole thing came about because of the crazy year I had [in 2006–07] touring with Clapton, the Allman Brothers and my own band. I was on the road constantly. The Clapton offer was a fantastic opportunity and something I could not say no to, but I also could not walk away from my other commitments. I had to grind it out, and it really made me want to have a great home rehearsal space just so I could be home more. That was my original goal, but once I realized that our guitar tech, Bobby Tis, and his father, who had been a consultant to studios and the chief engineer at Electric Ladyland, were capable of pulling off anything, I started to think bigger. We got a blueprint for a world-class studio and went for it. Because I was in the middle of the Clapton tour, I could swing it financially.

GW And recording there really impacted the way the CD came out?

TRUCKS Oh yeah. I loved having so much freedom to do whatever we wanted. It’s hard to balance this musical life with a family life, and the studio is an important part of trying to figure out how to do that. I wanted to incorporate recording music into normal family life—take the kids to school, then write and track a song.

The best example is “Back Where I Started.” Warren [Haynes] and I wrote that song together at the studio, and we recorded a version with him singing, which sounded great. But I wanted it to be more delicate— and to use the sarod [a fretless Indian classical instrument]—and he has such a powerful voice that it had a different vibe than what I was imagining. I wanted to hear Susan sing it, and I had a very specific sound in my head—what she sounds like first thing in the morning. We went out to the studio one morning after we had taken the kids to school, and I kicked everyone out so it was just the two of us, with the lights dimmed. You get a different performance when someone is not performing for anyone, and that epitomized the beauty of having a home studio. You can try different approaches without worrying about time or money.

GW You told me before that working with Eric Clapton had a big impact on you. Can you describe that and how it impacted the music on Already Free?

TRUCKS It was kind of a new thing for me to play things that straight, but I found that getting into the songwriting and making everything on the track serve the tune was really rewarding. Truthfully, I delved deeper into other music—blues, jazz and Indian—before I started really understanding much classic rock. The albums that I put on over and over are the ones that don’t reveal themselves all the way on the first listen but have something to keep pulling you back in. Stevie Wonder, Hendrix and Sly Stone are masters of that, and I wanted this album to be that way, with songs that always have a little more going on just below the surface.

GW What struck you most about Clapton’s guitar playing?

TRUCKS The fact that he doesn’t give it all away all the time. Something always seems to be boiling just under the surface, and he often keeps it there. I think the threat of something happening at all times is really powerful, and he’s a master of always leaving the crowd wanting more. I took notice of that, and I think there’s a lot of that in my playing on Already Free. This is our sixth studio record, and we’ve played hundreds of shows where we’re just leaving it all out there, so it felt like time for a different statement, where the guitar becomes another voice. That’s what we were trying to do.

GW I’d say it’s still the dominant voice, but you’re speaking in shorter sentences.

TRUCKS [laughs] That’s another impact of doing the Clapton thing. When you have two choruses to state the case, you don’t have time to warm up. You have to come out swinging.

GW All those years with the Allman Brothers must have prepared you for that as well. While there are many opportunities to stretch out, you also have to step up and hit the notes on songs like “One Way Out” and “You Don’t Love Me.”

TRUCKS Yes. After all those shows and all those solos, when I played shorter with Clapton I felt like I had another gear in reserve that I could always go to. You start to feel like you have some extra heat when you need it. The Allman Brothers is like a freight train, and there’s no room for any fear. You have to jump in and go when you have your chance. Since the moment I started playing with them, I had to feel confident enough stand toe to toe with Dickey Betts and Jimmy Herring and Warren and do my thing.

Derek, 2009. Photo by Michael Jurick

GW Your wife is also a touring musician, which must make it hard to have a normal home life. In the past two years, you have toured together as the Soul Stew Revival, which also includes your brother Duane on drums. Is that an attempt to merge your careers and will it continue?

TRUCKS Like a lot of things in life, you can look at both of us being musicians as either a blessing or a curse. Often, there’s a perfect solution staring you in the face, but you have to find it. For us, it was finding a way to tour together. I think we both need other outlets, but we are going to keep growing this and eventually record an album and keep pushing it toward a full-on rock circus. We already have 11 members.

The Allman Brothers thing is not going to last forever, and I think eventually the Soul Stew will occupy that spot of my year. My father also comes out and handles all the merch, and having him and my brother and my wife and kids all together on the road is a nice middle ground, where we can be out doing what keeps us alive and rolling while also keeping the family close and maintaining those bonds. We’ve all witnessed a lot of musicians with broken families—that seems to be really common—and I think it is possible to find a compromise where you can do it all and make it work. I think we’re slowly homing in on it, and the studio is a huge part of it, allowing us to do these albums ourselves from top to bottom.

GW There is a similarity between the microtonal bends in gospel and blues side guitar and Indian classical music, and you may well be the only one mining that cross-fertilization.

TRUCKS I first made the connection when I was going through a stage of listening only to straight-ahead jazz and Indian classical music. We were doing a tour of Mississippi and I was reading Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues, a great book that inspired me to pick up a Junior Kimbrough record. I was shocked, because the way he sang really reminded me of Indian singers in the bending of the notes and the mixing of major and minor. Then I started hearing the same connections in the guitar work, and it struck me that a lot of the music coming out of really difficult situations has those really difficult sounding notes. I had heard so much bar blues that I got sort of turned off to it, but that sent me back to my roots, plunging into blues guys like Son House, who can stand up to anything ever recorded in terms of emotional depth.

GW You explore those “difficult notes.” Does your new PRS Original Sewell amp help you enunciate them?

TRUCKS Yes. I have an old Fender Super Reverb that I have used for a long time with my band, because I love all of the subtlety that I can explore with it, but it just wasn’t powerful enough to use in the Allman Brothers. There, I have to solo over three drummers, a Hammond organ, a huge bass and Warren’s guitar. I got lost in the mix with my Super, and using a Marshall helped but it lacked the subtlety I needed. So the entire time I’ve been touring with the Alllmans, I’ve been struggling to find the right sound. When I took the PRS Original Sewell head out, it was the first time I finally felt relaxed about my sound and could just play without thinking about it. I think it’s the perfect middle ground where I can get the subtlety I get with my Super but also put the pedal down when I need to. I finally feel like I don’t have to compromise part of my sound.

July 7, 2014

Allman Brothers announce sale dates for final concerts

Photo by Dino Perucci.

Finally, some news we’ve been waiting for… tickets for the final Allman Brothers concerts go on sale next week… Please note that the information below is a press release from the band without any editorial input or commentary from me… and also note that there is a presale for members of the band’s Peach Corps fan club.. if that’s you, go find that info!

**

ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND ANNOUNCE ON-SALE INFO FOR FINAL CONCERTS

FOUR POSTPONED BEACON THEATRE

SHOWS IN NEW YORK CITY SET FOR OCTOBER 21, 22, 24 & 25

AND FINAL TWO CONCERTS OCTOBER 27 & 28

The ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND have announced the on-sale information for the final shows for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame group that formed in 1969. Tickets for their October 27 and 28 performances at New York City’s Beacon Theatre will go on sale to the public Friday, July 11 at 10:00 AM Eastern. These final ABBperformances bring the band full circle back to the Beacon, a venue the band has played exactly 232 times since their annual tradition began there in 1989.

This comes after the news that the band rescheduled dates for four shows at theBeacon Theatre that were postponed in March: Tuesday, 10/21, Wednesday 10/22, Friday, 10/24 and Saturday, 10/25. Tickets purchased for those sold-out shows (originally set for 3/25, 26, 28 & 29) will be honored on these dates for the corresponding days (see itinerary below). Fans unable to attend the rescheduled shows can return tickets for a refund at the point of purchase prior to August 1.

As part of the 45th anniversary celebration, the band recently released a new DVD 40, filmed at the Beacon on their 40th anniversary, where they performed their first two albums The Allman Brothers Band and Idlewild South in their entirety. Their monumental breakthrough live album At Filmore East (cited by Rolling Stone on their list of 25 Best Live Albums) will be celebrated by Universal Records with the July 29 release of a six-CD set.

The current lineup of the band–founding members GREGG ALLMAN (vocals and keyboards), BUTCH TRUCKS (drums and tympani) and JAIMOE (drums) plus longtime members WARREN HAYNES (vocals, lead and slide guitar), DEREK TRUCKS (slide and lead guitar), OTEIL BURBRIDGE (bass) and MARC QUINONES (congas and percussion)–is, at 14 years, substantially longer than any other version of the band.

Meanwhile, the band is gearing up for two nights of concerts as part of their very own PEACH FESTIVAL, August 14-17 in Northeast Pennsylvania. In its third year, PEACH FEST 2014 will feature artists including the ABB on two nights,Gov’t Mule, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Jaimoe’s Jasssz Band, Bob Weir & Ratdog, Trey Anastasio Band, Lotus, Big Gigantic, the Taj Mahal Trio, Blackberry Smoke, George Clinton & Parliament Funkadelic, the London Souls and more. TheALLMAN BROTHERS BAND will close the Lockn’ Festival in Arrington, VA onSunday, September 7.

Tickets for the October 27 & 28 Beacon Theatre shows go on sale to the publicFriday, July 11 at 10AM ET and can be purchased at www.ticketmaster.com andwww.beacontheatre.com and via charge by phone at 866-858-0008. If tickets remain, they will also be available at the venue box office beginning Saturday, July 12 at 11:00AM. American Express® Card Members can purchase tickets before the general public beginning Tuesday, July 8 at 10AM ET throughThursday, July 10 at 10PM ET.

Here is the band’s final itinerary:

DATE: CITY: VENUE:

Sat-Sun 8/16-17 Scranton, PA Peach Fest

Sun 9/7 Arrington, VA Lockn’ Music Fest

Tues 10/21 New York, NY Beacon Theatre (tickets for March 25 honored)

Weds 10/22 New York, NY Beacon Theatre (tickets for March 26 honored)

Fri 10/24 New York, NY Beacon Theatre (tickets for March 28 honored)

Sat 10/25 New York, NY Beacon Theatre (tickets for March 29 honored)

Mon 10/27 New York, NY Beacon Theatre

Tues 10/28 New York, NY Beacon Theatre

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

June 20, 2014

Horace Silver’s surprising Allman Brothers connection

RIP Horace Silver, a jazz giant whose music could be catchy without being simple, whose musical depth is often overlooked and who was a co-founder of the Jazz Messenger with Art Blakey… and who has a surprising Allman Brothers connection.

RIP Horace Silver, a jazz giant whose music could be catchy without being simple, whose musical depth is often overlooked and who was a co-founder of the Jazz Messenger with Art Blakey… and who has a surprising Allman Brothers connection.

This is a very cool remembrance by a WSJ reporter who is also a fine pianist and had a lengthy correspondence with Mr. Silver. I think it captures a lot more than a standard obituary does.

I loved Horace Silver’s music and Dickey Betts is a big fan of it as well.

At the end of a lesson interview we did with him in 1996, Guitar World Music Editor Jimmy Brown and I were walking out of the hotel room when Dickey called us back and said to Jimmy, “Do you know Horace Silver’s The Preacher. It would be a blast to play it with a fine guitarist like you.” And the two of them went to town, both kneeling on the floor because neither had a strap on their guitar. A very memorable moment for me, and the kind of little vignette that just didn’t fit into One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

Dickey circa ’74. Photo by Sidney Smith

And a few years later, Dickey was out of the ABB and back with Great Southern – and he’s playing “The Preacher.” I sat in front of the stage at BB King’s and heard the following:

Dickey had been playing the song for many years:

A few choice Horace cuts:

Horace’s original “The Preacher”:

“Song for My Father,” which Steely Dan sort of sampled for “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”:

// ]]>

Amazon.com Widgets

June 16, 2014

Special gig this Friday June 20 in Maplewood

Saxophonist Dave Loevinger, one of my partners from Beijing’s Woodie Alan band will be in town and joining the Big in China band for a very special show.

Saxophonist Dave Loevinger, one of my partners from Beijing’s Woodie Alan band will be in town and joining the Big in China band for a very special show.

THIS FRIDAY, June 20 at Highland Place Bar and Grill.

8:30 PM

5 Highland Pl, Maplewood.

More info and RSVP here.

Dave is a great, great player who raises the stakes every time he plays a solo and we have a tremendously fun and meaningful history together.

You read about him in Big in China. Now come on out and see him with the Big in China band.

Here’s a fun clip of Dave and I in Woodie Alan, playing at the JZ VClub in Hangzhou, China. His solo that drove the crowd wild begins at 4:54:

And here’s a recent clip of the Big in China band:

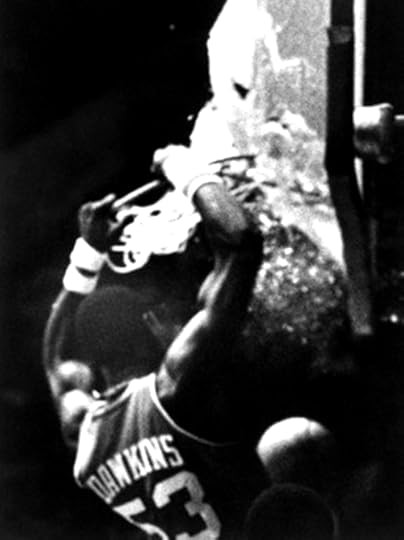

Chocolate Thunder – the Slam interview

Posting the picture of me and Darryl Dawkins in the Shanghai Ritz Carlton lobby in 2007 on Facebook generated a lot of feedback and prompted me to dig this Slam feature out of the archives. I think it’s a classic of my oeuvre.

Posting the picture of me and Darryl Dawkins in the Shanghai Ritz Carlton lobby in 2007 on Facebook generated a lot of feedback and prompted me to dig this Slam feature out of the archives. I think it’s a classic of my oeuvre.

It ran in approx. 2000 and I reran it here on Halloween, 2007. Enjoy.

*

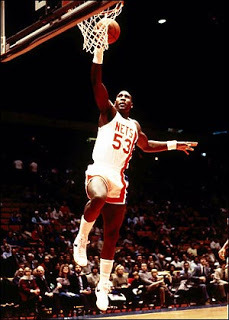

Darryl Dawkins is a patron saint of Slam, because he is a patron saint of slam. The National Dunker’s Association of America named Dawk to it s list of 30 greatest slammers of all time, but he may well rank at the very top of the list, above even Mike, ‘Nique and Doc.

Like them, Double Dee was a pioneer, the first baller to do many things that we now hold near and dear to our hearts. He was the first to shatter a backboard. The first to name his jams. The first to go directly from high school to the NBA. The Chocolate Thunder was also the first NBA player we know of to claim he was actually an alien from the planet Lovetron. It all added up to him recently being named “Man of the Millennium” by Saturday Night Live, edging out William Shakespeare and Albert Einstein.

But to explore that avenue any further would be to propagate the idea that Dawkins is some kind of joke, a hoops freak show to be laughed both at and with. And that’s too easy a path to take. Because something can be funny without being a joke, and that’s exactly the case when it comes to The Master of Disaster, Darryl Dawkins.

In 1975, Dawkins, a senior at Maynard Evans High School in Orlando, FL, announced he would go directly to the NBA to the snickers of many. Drafted fifth by the 76ers, Dawk did not set the league on fire his rookie year, averaging just 2.4 ppg. Still, he quickly developed into a solid low post contributor and by his second season, the Sixers were in the Finals, where they lost to Bill Walton and Maurice Lucas’s TrailBlazers. Dawkins and the Sixers would return to the Finals twice more only to lose. Fact is, they could- shoulda won either or the ‘81 and ‘82 series against Magic’s Lakers, which would have radically rewritten both the history of 80s hoops and Dawkins’ place in the basketball cosmos.

“Dawkins was an incredible physical specimen,’ recalls Bob Costas.” He was 6-11 and 275 pounds and no one had ever seen anything like him to that point. He was a manchild and everyone was actually terrified of him.”

Including the refs, who never gave the benefit of the doubt to the bad-ass-looking guy swatting shots, glaring down opponents and occasionally delaying games for hours while new backboards were installed. Dawkins led the league in fouls three times and still holds the record for most personal fouls in a season (386). By the end of his 14-year career, Dawkins relied largely on his muscle and ferociousness, a natural evolution for a guy who never met a confrontation he didn’t relish. But Dawk was no mere thug. He is the fifth most accurate shooter in NBA history with a field goal percentage of .572.

Post-NBA, Dawk spent five years playing in Italy and one as a Harlem Globetrotter. Now he has defied virtually all expectations by becoming a very successful minor league coach. The last two years, he has coached both the Pennsylvania Valley Dawgs of the U.S. Basketball League and the Winnipeg Cyclones of the International Basketball Association, for whom he also played last year. He has been coach of the year in both leagues.

Prowling the sidelines at a recent Valley Dawgs game, Dawkins cuts an imposing figure in his mustard suit, gold hoops dangling from both ears, his chocolate dome shaved smooth. On the court, his squad runs and presses mercilessly, driv

ing their opponent into submission. Despite a commanding victory, Dawkins is stern in the postgame locker room, saying, “If the big guys can’t get it done, I’ll go out and find me some who can.” He doesn’t rule out suiting up himself to show the youngsters how it’s done.

Afterwards, in between flirting with departing dancers and making friendly, funny small talk with everyone from the Valley Dawgs owner to their ball boy, Dawkins gave some love to the only magazine that could ever truly appreciate his brilliance.

SLAM: You have a lot of nicknames, but the most enduring is Chocolate Thunder. Where did it come from?

DAWKINS: A kid I visited at Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia said I was like a mass of chocolate, so I started calling myself Chocolate. Then Stevie Wonder wrote a song that said, “I’m bad like Stevie Wonder and strong like Chocolate Thunder” and I loved that. So I’ve been the Chocolate Thunder ever since.

SLAM: When did you start naming your slams?

DAWKINS: In 1976 when I wound up on the Sixers team with George McGinnis, Dr. J, World B. Free and Doug Collins. That was a great, great group of players and I needed to do something so people would know I was on the team too. So I decided to name my dunks and have a calling card.

My first one was “Your Mama,” then came “The Heartstopper,” “The Cake Shaker,” “The Baby Maker,” “The Turbo Sexaphonic Delight” and “The Left Handed Slam Chiller’s Delight.” Then “The Chocolate Thunder-Flying Glass-Babies Crying-Rump Roasting-Bun Toasting-Teeth Shaking-Babies Still Crying-Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am-Yes I Am – Jam.”

SLAM: What was the best one ever—not the name, but the slam.

DAWKINS: “Your Mama” [laughs] I always liked that because if some guy tries to block your shot and throw it down on him, you just look him in the eye and say, “Your mama.” Simple but effective. Really, it doesn’t get any better than that.

SLAM: Were your backboard smashings intentional?

DAWKINS: The first one I broke was accidental. Then I had to see if I could do it again so the second one was quite intentional. Once I found out I could, I was actually going to do it some more, but they said they were going to fine me $5,000 every time I broke one after that. And that put an end to that.

SLAM: Besides, they made the breakaway rims, which is one of your great contributions to the game.

DAWKINS: They can still be broken! I broke two in Italy. You just have to dunk it from the side. It collapses from the front, but not from the side. If you hit it hard enough from the side, it will go, as I have proven. SLAM: Do you see any current players following in your large footsteps?

SLAM: Do you see any current players following in your large footsteps?

DAWKINS: Take the strength of Shaquille O’Neal and put it together with the freedom of Dennis Rodman, and you have the Chocolate Thunder. Like Rodman I was going to do what I wanted to do and I wasn’t going to let anyone control me, which is what the Sixers and other teams tried to do. They wanted to tell me where to go when and with whom and I didn’t want that.

SLAM: Is that part of the reason you decided to not go to college?

DAWKINS: No, I actually wanted to go to college but my family was in financial difficulty. I was able to do things to help them out. I had seen my mother and grandmother work their fingers to their bones and I could end that. I was able to put brothers and sisters as well as cousins through college, instead of just going myself. That’s why I took that route. As far as not wanting to be controlled, let me make this clear: I didn’t want to just do the wrong thing. I just wanted to make my own decisions and not have someone dictate to me: “You are gong to do this, because we want you to.” That’s not a good enough reason.

SLAM: When you went pro right out of college, could you ever have imagined that it would be a common occurrence 25 years later?

DAWKINS: No, because it was unheard of at the time. People thought I was crazy because I was the first one with the audacity to try. Moses [Malone] went to the ABA the year before, but that was different. Nor did I think I would ever be coaching, but you never know what lies down the road.

I think the only reason you go to college is to get a good education and make good money to support your family. If you can make the money right then and still get an education on your own schedule, you got to go for it, because it’s your dream. What happens if you get in a car accident and never get to the pros? What happens if you blow out your knee? If you have the skills and it’s your dream, you go to go for it.

SLAM: But what gave you the confidence to think you could play against Artis Gilmore and Kareem Abdul Jabbar just because you could dominate in high school? That’s a huge leap.

DAWKINS: I believed in myself. I had six brothers and four sisters and growing up in a big family like that I learned that there’s nothing that can’t be done if you work hard enough for it. It had never been done before in the NBA but I really believed I could do it. I just felt that I could. I had a lot of confidence and my pastor, Rev. W.D. George, believed in me, as did my mother. And they were just about the only ones besides me who believed I could pull it off. A lot of people I grew up with said, “You’ll be back home standing around here in a year or two.” Well, it’s 25 years later and I’m still not back in Florida.

SLAM: That Sixers team you came on to was loaded with great players.

DAWKINS: We had so much talent that we actually forgot we had to play some nights. Look at who we had: Julius Erving, who was Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan; George McGinnis, an incredible player. Doug Collins, a super talented super guy, and World B. Free – one of the best shooters ever.

SLAM: Yet as good as the team was, you never won a title.

DAWKINS: I just think when we played Portland and LA, they were better teams. You just have to realize that. Everyone thought we should have won a championship, but we met our match. They also had great talent, but played more unselfishly, with more of a team concept.

SLAM: Were you surprised when Maurice Lucas took you on in the middle of a scuffle with Bobby Gross, another Portland player?

DAWKINS: No. I was surprised that my teammates let him approach me from behind. He hit me from behind, then we squared off but never got a chance to go because everyone separated us. Then I turn around and Julius is sitting on the ground and George McGinnis is picking his nose. If someone’s running up behind my teammate, I’m going to grab him or do something to stop him. But I don’t carry any grudges about that. It was a long time ago.

SLAM: Let’s talk about what made those guys so good, starting with George McGinnis

DAWKINS: He was big, strong and quick. And he knew the game. He had a great one-handed shot.

SLAM: What was Doug Collins’ game like?

DAWKINS: He was great, a very underrated player. Doug was a tremendous force in college and he would have been as a good as Larry Bird if it weren’t for injuries. He had a bum arch in his foot and kept getting hurt, but he was a Bird type of player. He could run and jump, shoot and pass and rebound. And he could play great defense, which a lot of big guys today don’t do.

SLAM: What about World B. Free?

DAWKINS: World B. Free is still my brother, and he was the original Boston Strangler. I often hear people say Andrew Toney is the best shooter they ever saw, but World was better, man. He and I played one on one every day after practice and he helped me a great deal with my ballhandling skills because he would take it from me every time I put it down.

He also showed me one of the great keys to my game. One night, he took it down the middle and dunked on Bill Walton, a great shot blocker, and I said, “Damn, man, how did you do that?” And he said, “You can do it, too.” And I went out and I dunked on Walton myself. After that I started dunking on everyone, with no fear. It was just a matter of having the confidence to go try it, and World B. Free showed me that. For that, I am forever grateful.

SLAM: How good was Walton in his prime?

DAWKINS: Bill Walton was a great player, but his supporting cast was also incredibly strong, which made him better. He was surrounded by guys who just wanted to win and didn’t care who scored. And that’s why they won. LA was the same way – only a few guys had to have the ball. Everyone else played a role. Everyone on our Sixers team wanted the ball all the time, and that hurt us. We had guys who had to be scoring to be happy. And that makes a big difference.

SLAM: Was that frustrating?

DAWKINS: At times, very much so. Because you had to do what the stars didn’t do, and you didn’t know what that may be on any given night. One night somebody’s shot’s not falling so you have to go score. Another night, you just need to rebound and play d.

SLAM: You were briefly with the Pistons.

DAWKINS: Yeah, I played with Rodman and Isiah and them for a bit. I thought they got rid of the most talented guy on the team in Adrian Dantley. He did it all, but if you didn’t get along with Isiah Thomas, you didn’t stay in Detroit. That’s a fact.

Rodman was just becoming a force on the boards, and John Salley was also a talented guy. He wasn’t too tough but he could score and block some shots. And Rick Mahorn and I have been buddies forever and we still are. When I played with the Nets, Rick and Buck Williams got in so many fights that Larry Brown would always switch me onto Rick because he knew we were friends and we wouldn’t fight. Buck was getting thrown out of every game, because Rick would just knock the crap out of him and drive him nuts. And Buck was a tough guy himself.

SLAM: Now, I know you’re buddies with Rick, but was he a cheap player?

DAWKINS: He was a nice guy. Honestly. Everyone misunderstood him. We always had a good time. In fact, I always used to call his mother, God Rest her Dead, “Mama Mae Mahorn” after a dj on Kiss FM and we always joked about that on the court. I never thought he was cheap. I thought he did what he had to do to be where he wanted to be.

SLAM: What about Laimbeer?

DAWKINS: Cheap.

SLAM: Meaning what? Would he hit you from behind before you could turn around?

DAWKINS: I used to get him from behind. I’d get him before he could get me. Once when I was with the Nets, I gave him a kidney punch and he went down. [Referee] Jake O’Donnell said to me, “Darryl, if you hit the white boy again, you’re out of the game.” After that, Bill was a little afraid of me, because I was pretty physical myself. So he kept his distance. But, hey, there was more to him than that stuff. He was a good, heads-up player. He knew just what he could do to get inside someone’s head, but I never let him get into me.

Look at Dennis Rodman. He got in everyone’s head, but he didn’t bother Charles Barkley. He didn’t bother Charles Oakley. And he wouldn’t bother me, because he knew we didn’t give a fuck. We’d just turn around and brawl with him. Other guys would want to try and stay in the game but we didn’t give a fuck. And if you have that going for you, no one’s starting anything, believe me.

SLAM: Were there any guys you knew not to mess with?

DAWKINS: I don’t fear anyone, and I never did. Even now, I don’t fear a saber-toothed tiger; I just don’t fuck with one. And I’m not alone. There are lots of guys who have never been scared of anyone. You just do what you got to do to take care of yourself. The guys who play today want to shoot each other and cut each other and all this if there’s trouble on the court, but that’s crazy. We fought each other hard, wrestled each other. And in the end, we all got together and had a beer. That’s a big difference.

SLAM: Were there guys who you knew once good forearm would take them out of the game?

DAWKINS: Yeah, but I don’t want to do that to them. They know who they are. Guys who you hit them at two feet, they go to four. You hit them at four feet, they go to six. They were easy marks.

Letters from Oteil and readers – feedback is always welcome

Oteil: “Thank you for this wonderful book. What a gift to receive it at the end of this chapter of my career. You helped me put the last 17 years of my life in perspective.”

So I saw Oteil behind the Mushroom Stage at Wanee and he gave me a big hug and said, “Thank you for this wonderful book. What a gift to receive it at the end of this chapter of my career. You helped me put the last 17 years of my life in perspective.”

Well, heck Oteil – thank you. What a message to get.

And what a pleasure it has been to receive constant feedback from readers of One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. they come by email via this site, through soe actual letters and through voluminous postings and letters on my Facebook Page, which I urge you to like and follow.

Here is a sampling of some of the great feedback. Thank you all. I feel honored to have been able to chronicle so much history of this band we love for you all and appreciate hearing from everyone about how the music has impacted your lives.

•

Hi Alan, You may know me as Mr. Belding from a TV show called saved by the bell but, back in 1979, I was the unofficial road manager, along with David Cloud of Momma’s Pride, of a brief tour with Gregory, Momma’s Pride and Overland Express that ended with the Allman Brothers reuniting!

I joined up after two separate trial gigs. One was in Myrtle Beach and the other in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which is where I’m from. Paul Burke in Daytona Beach was someone Gregg trusted and who I knew from Chattanooga. He knew suntan oil and I knew the music business. He asked me to come help after I saw them in Chattanooga. I jumped in my car the next day and drive to Daytona. 30 something shows of Gregory showing up and gaining strength personally, musically and draw-wise later, I watched The Allman Brothers reunite, first as a surprise reunion in Central Park after Great Southern played and finally reformed at the Capricorn picnic in Macon.

It was an amazing time and I would love to share this with you. I saw you on Imus and know you are the right guy to share this with.

Cheers, Dennis Haskins

*

Alan

I finished your book… I had planned on reading it up to the about 1979 or ’80 and then not getting into all the additional negative stuff I knew was coming. But I didn’t. I kept reading thanks to your fine presentation, and to a degree, the “train wreck coming” factor.

I worked with the band once in 1980 or so when Bill Hoyt stage managed and Dan Toler and David Goldflies were in the band and Steve Massarsky was their attorney so I had a small personal interest as well.

I’m glad I kept reading. Thank you.

I do have a note to add that you may or may not have noticed in your research. As you know, distinguishing Dickey’s playing from Duane’s was a game many of us played in their early years. I got my information about how to do that from a conversation with a friend in the about ’73 when a bar band named Wart Hog was just playing the hell out of the ABB’s music in San Luis Obispo, California every night at a bar named “The Irishman” but routinely called simply “The I.”

Your interviews with Dickey and others confirm what I had been told. Rounder tones, etc. But I’m sure there were hundreds of thousands of fans who were sent off on the wrong tack for many years and had the opposite rule of thumb to rely on until they were able to see the band live.

That misinformation comes from, of all places, the liner notes in “Beginnings.” In the fifth paragraph, Jean-Charles Costa notes, “(if you listen a lot it’s not hard to tell them apart–Dickey’s guitar has a harder edge metallic ring to it. Duane’s has a smoother, ’rounder’ tone).”

Obviously this is directly contradictory to Dickey’s comments to you in your book that, “He [Duane] had a spitfire, trebly sound with staccato phrasing and . . . my thing was more of a rounded-tone sound . . ..”

I think Mr. Costa really screwed that up. I wonder if he ever learned of his error.

Thanks for the great book; I really enjoyed it. Even the train wreck parts.

-Randolph Neel

Very interesting and kinda crazy about the Beginnings notes. Thanks for pointing that out. -AP

Reader Sarah Cornell made me this slamming sign and gave it to me at Wanee.

*

Hi Alan, just wanted to drop a quick note to you. I read your book and it was amazing! I was at the event at Eddie’s Attic a few weeks ago, and it was really great. I’ve been up to the Beacon run about 5 times, and I’ve caught them about 25 times over the past 10-15 years. I have a band in Atlanta (www.reverbnation.com/thebitteroots) and The Allmans are the main reason I play music to this day. Thank you so much for your energy and hard work pulling all this together and spreading the good vibes of the greatest band ever, The Allman Bros. Band!*

Perhaps it might seem strange to some people that a person I never met could have such a profound affect on me, but Duane Allman literally altered the course of my life with the emotional intensity of his playing. Your book, as much as anything could, helped to make a connection to where that music came from.

Thanks again,

Bill Taylor

•

Hi Alan…first, congrats on One Way Out. It arrived in the post yesterday, and I finished it this morning over breakfast. Without a doubt the best book on the ABB. Thanks.

-Rick H

*

I felt compelled to write to you after reading your book this weekend.

I first saw the ABB at the Nassau Coliseum on April 30, 1973 (yes, the day before the archival release date). A friend of mine was into them and suggested we go check them out. I listened to some of the Live at Fillmore Album, definitely liked it and was anxious to see them. We had great seats on the orchestra floor but i really didn’t know that i was about to be transformed. I was 17 and had never seen music like that before. Everyone knew Gregg Allman, but in the same breath most everyone was talking about Dickey Betts’ performance after the show. The drum solo and Chuck were great conversation items too. I became a big fan, saw them whenever I could and knew a lot about them…so i thought. Your book was phenomenal. It was riveting, interesting and insightful. You gave me a whole different perspective on the band, most poignantly Duane’s effect on the band for years after. Simply…great work, and thank you.

Mark

Anne Zcukerman Minkin reads while her husband, photographer Bob Minkin flies her around.

*

Just finished One Way Out and LOVED it. Great job. I particularly liked their thoughts about ensemble playing, phrasing, tone, and how each new bassist came to understand the groove of Jaimoe and Butch as a singular thing. Just great.

-Neil

•

This is TJ Klay from Nashville Tennessee. I am a harmonica player /singer-songwriter by trade and am in a band with both Reese Wynans and Richard Price. Richard will talk “Duane” all day long with you if you let him. I’ve tried to be more respectful with Reese and not ask too many questions and let him talk about it when he wishes to.

When I started playing the harmonica, I used Duane’s slide playing as a blueprint and he has probably influenced me more than any other musician to date.

I want you to know how good I thought One Way Out was. I discovered the ABB as a junior in high school & have never been without Live at the Fillmore since. Had the vinyl, had the eight track, the cassette, CD, remastered CD, CD of alternate takes… you get the picture.

It was brilliant to have the story told by those who were there and you did a excellent job compiling it and doing what needed to be done with that information. I found myself being really sad nearing the end of the book, knowing that I could never read another book about them as good as this.

… I just wanted to know I love the book and just how special it was for somebody like to read, only to find there was a lot more exciting stuff that had never been covered before!

AFan,

~ TJ Klay

*

Just want to say thanks for “One Way Out” – a great read. I first heard of the ABB when their first album was released and played on air by a progressive jock in NYC. The love affair has continued now for 45 years even though the first 4 albums – the Duane years – cannot be matched. In any event, the book was masterful and you deserve tons of credit for having taken on such a daunting task. I hated finishing the book, but I guess the road doesn’t really go on forever.

-Larry Sand