Voynich Reconsidered: Exon Domesday (Part 2)

Many researchers of the Voynich manuscript have remarked on the similarities between certain glyphs and some abbreviation symbols used in medieval Latin texts. The work of the archivist Adriano Cappelli lends support to this observation. This permits us to advance the hypothesis that the Voynich scribes worked from precursor documents in abbreviated Latin.

To test this hypothesis: as with other possible precursor languages that I have investigated, to my mind the first step is to look for statistical relationships.

If we could find a machine-readable text in abbreviated Latin, of at least 50,000 characters, we could test its statistical correlation with the Voynich manuscript. In my search for such a text, I considered the Exon Domesday, a part of the Domesday Book commissioned in 1086 by King William of England. In my attempt to process the Exon Domesday, I ran into an obstacle in terms of the sheer labor-intensity of the work.

My starting point was the excellent Exon Domesday website at https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/. The site includes images of the original manuscript; scans of the 1816 printed edition transcribed by Ralph Barnes and published by Sir Henry Ellis; and a modern transcription into expanded conventional Latin (I believe, by Dr Frank Thorn).

The manuscript is not machine-readable (at least, not with any software to which I have access). The 1816 edition reproduces the original abbreviations in a modern typeface, but can only be downloaded one page at a time, then subjected to optical character recognition which yields a multitude of errors.

Dr Thorn’s transcription is fully machine-readable, but replaces the abbreviations with expanded strings of letters. Fortunately, the expanded strings are written in italics. Microsoft Word has a find-and-replace function which can distinguish italics from regular font. Thus, it should be possible to reconstruct the abbreviations while preserving the machine-readability of the text.

Accordingly, I devised the following process for restoring the abbreviations:

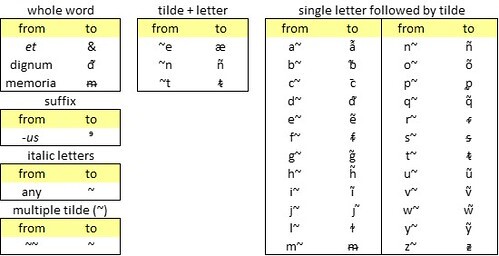

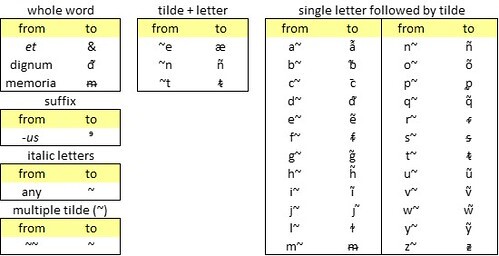

An experimental algorithm for restoring Latin abbreviations to a expanded Latin text in which abbreviations are represented by text strings in italics (~). Author’s analysis.

The following is an example of this process, applied to a short extract from Dr Thorn’s transliteration:

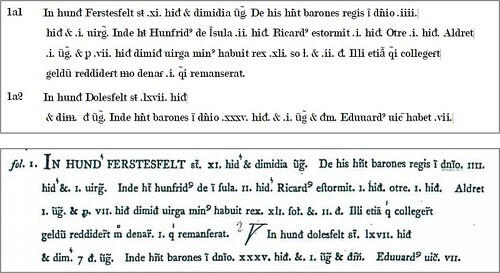

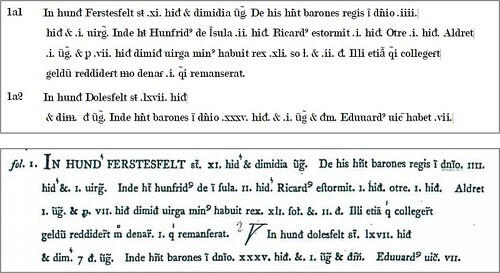

Exon Domesday, folio 1, lines 1-5. (above) An algorithmic restoration of the Latin abbreviation symbols, applied to sections 1a1 and 1a2 of Dr Frank Thorn’s transcription; (below) the same lines from the Barnes-Ellis printed edition published in 1816. Author’s analysis.

Thus, with an objective algorithm, we are able to create a close approximation of the Barnes-Ellis edition of 1816, and what is better, one which is machine-readable and is not subject to the errors inherent in optical character recognition.

Next steps

As an experiment, I applied my algorithm to sections 1a1 through 2a1 of Dr Thorn's transcription. My reconstructed text has 6,557 characters, of which 5,498 are letters or abbreviation signs represented by Unicode symbols. This sample is still too small for robust statistical analysis.

A logical next step would be to assemble a longer extract from Dr Thorn’s transcription, say of at least 10,000 characters, and apply the same algorithm for the restoration of the Latin abbreviation signs. If the result is a satisfactory approximation of the Barnes-Ellis transcription, the frequency distribution of the characters should have greater statistical significance (as compared to those of the shorter extracts that I have produced).

We could then attempt another comparison of the frequency distribution with those of conventional Latin corpora, and with those of selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript.

To test this hypothesis: as with other possible precursor languages that I have investigated, to my mind the first step is to look for statistical relationships.

If we could find a machine-readable text in abbreviated Latin, of at least 50,000 characters, we could test its statistical correlation with the Voynich manuscript. In my search for such a text, I considered the Exon Domesday, a part of the Domesday Book commissioned in 1086 by King William of England. In my attempt to process the Exon Domesday, I ran into an obstacle in terms of the sheer labor-intensity of the work.

My starting point was the excellent Exon Domesday website at https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/. The site includes images of the original manuscript; scans of the 1816 printed edition transcribed by Ralph Barnes and published by Sir Henry Ellis; and a modern transcription into expanded conventional Latin (I believe, by Dr Frank Thorn).

The manuscript is not machine-readable (at least, not with any software to which I have access). The 1816 edition reproduces the original abbreviations in a modern typeface, but can only be downloaded one page at a time, then subjected to optical character recognition which yields a multitude of errors.

Dr Thorn’s transcription is fully machine-readable, but replaces the abbreviations with expanded strings of letters. Fortunately, the expanded strings are written in italics. Microsoft Word has a find-and-replace function which can distinguish italics from regular font. Thus, it should be possible to reconstruct the abbreviations while preserving the machine-readability of the text.

Accordingly, I devised the following process for restoring the abbreviations:

• replace certain whole words such as et (in italics) with the corresponding standard abbreviations (in regular font)The algorithm is summarised below.

• replace the suffix -us (in italics) with the abbreviation ⁹ (in regular font)

• replace all other letters in italics with the Unicode symbol ~ (tilde); for example hundreto becomes hund~~~~

• replace all resulting strings of ~ with a single ~; for example ~~~ becomes ~

• replace all occurrences of, ~e with æ, ~n with ñ, and ~t with ᵵ; for example h~nt (from habent) becomes hñt

• in any other occurrence of a letter followed by ~, replace it with the same letter with embedded tilde.

An experimental algorithm for restoring Latin abbreviations to a expanded Latin text in which abbreviations are represented by text strings in italics (~). Author’s analysis.

The following is an example of this process, applied to a short extract from Dr Thorn’s transliteration:

Exon Domesday, folio 1, lines 1-5. (above) An algorithmic restoration of the Latin abbreviation symbols, applied to sections 1a1 and 1a2 of Dr Frank Thorn’s transcription; (below) the same lines from the Barnes-Ellis printed edition published in 1816. Author’s analysis.

Thus, with an objective algorithm, we are able to create a close approximation of the Barnes-Ellis edition of 1816, and what is better, one which is machine-readable and is not subject to the errors inherent in optical character recognition.

Next steps

As an experiment, I applied my algorithm to sections 1a1 through 2a1 of Dr Thorn's transcription. My reconstructed text has 6,557 characters, of which 5,498 are letters or abbreviation signs represented by Unicode symbols. This sample is still too small for robust statistical analysis.

A logical next step would be to assemble a longer extract from Dr Thorn’s transcription, say of at least 10,000 characters, and apply the same algorithm for the restoration of the Latin abbreviation signs. If the result is a satisfactory approximation of the Barnes-Ellis transcription, the frequency distribution of the characters should have greater statistical significance (as compared to those of the shorter extracts that I have produced).

We could then attempt another comparison of the frequency distribution with those of conventional Latin corpora, and with those of selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript.

Published on May 15, 2024 08:52

•

Tags:

exon-domesday, frank-thorn, henry-ellis, ralph-barnes, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers