Voynich Reconsidered: multiple alphabets

In the final chapter of Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, 2024), I attempted to imagine the workplace where the Voynich manuscript was produced. Undoubtedly there was a team of scribes: Dr Lisa Fagin Davis has identified five distinct hands, though we have no way of knowing whether they worked together or separately. In my imagination, I saw a producer: a wealthy individual who conceived the project, paid for the labor and materials, and gave instructions to the scribes as to how they should proceed.

In previous articles on this platform, I expressed the view that the producer would have wished to give the scribes a simple set of instructions, whereby they could write the text with minimal supervision. Furthermore, such instructions had to yield a text in which, within nearly every “word”, the glyphs followed a relatively strict sequence, of the kind that Mary D'Imperio and Massimiliano Zattera observed.

As a working assumption, I conjectured that the producer provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages, together with a simple system for mapping letters to glyphs. A relatively undemanding rule could be as follows: take one word at a time, first transcribe the letters to glyphs, then re-order the glyphs in each "word" according to a "Voynich alphabet".

Zattera's "alphabet"

Zattera's "slot alphabet" describes a process for such a re-ordering. However, with Zattera's alphabet, the scribes would need to know where to place the "nomadic glyphs". For example, should a v101 glyph {8} be in slot 0, 7 or10? In Zattera’s alphabet, all three are permitted.

Zattera’s "slot alphabet". Glyphs which can be in multiple "slots" are marked in cells with solid borders. Graphics by author. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2oj1sYr.

Trying to step into the Voynich producer's shoes, I could imagine that he or she might define two or more "slot alphabets". Perhaps in one alphabet, {8} is always in slot 0; in the second, always in slot 7; in a third, always in slot 10.

We might see evidence of such multiplicity if we subdivide the manuscript in various ways. There are at least three such ways, as follows.

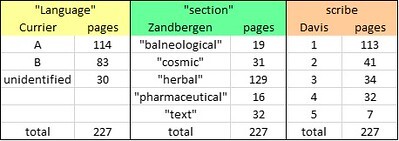

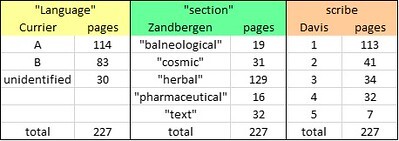

Three ways to subdivide the Voynich manuscript: by "language" (after Prescott Currier); by thematic "section" (after René Zandbergen); and by scribe (after Dr. Lisa Fagin Davis). Author's analysis.

To test this hypothesis, we could invite Mr Zattera to re-run his program on Language A and B separately; on each of the themed sections; and on the pages written by each of the five scribes.

As a low-tech alternative to re-running Mr Zattera’s program: it occurred to me that we could subdivide the Voynich manuscript in the three ways proposed above; in each subdivision, select the most frequent “words” (say, the top five or ten); test each of these “words” for conformity with Zattera’s “slot alphabet”; and examine whether there is any version of the “slot alphabet” that best fits the subdivision.

"Languages"

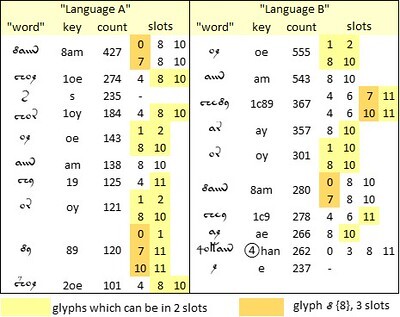

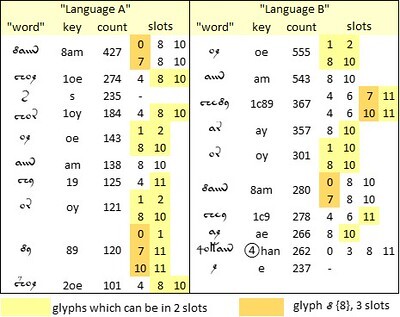

Below are my results for the subdivision by “language”.

The ten most frequent "words" in the "Language A" and "Language B" pages of the Voynich manuscript, as defined by Currier. Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQLeDP.

Here we can see that in both “languages”, at least among the top ten “words”:

"Sections

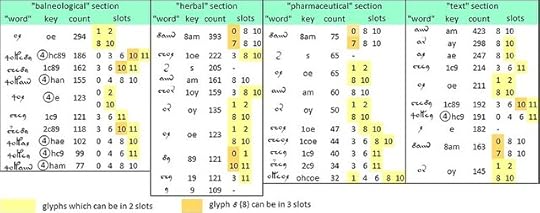

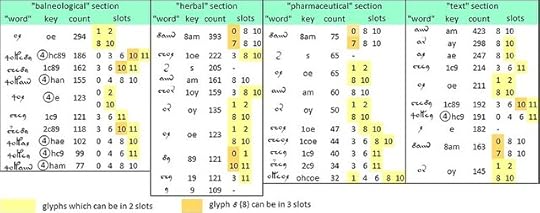

However, the same exercise on the thematic sections reveals a substantial differentiation in vocabulary and in conformity to the “slot alphabet”.

The ten most frequent "words" in the four major thematic sections of the Voynich manuscript; and the conformity of each "word" to Zattera's "slot alphabet". Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQSf8d.

Here we see that the “balneological” section has a distinctive vocabulary, in which the top ten “words” are dominated by “words” beginning with ④, and only two “words” are in common with the other three sections. This result suggests that in this section, either the precursor documents were in a different language, or the rules for transcribing letters to glyphs were in some sense unique. That is, the “balneological” section may have a different alphabet from the others.

It is as if the producer specifically allocated the glyph ④ to the “balneological” section, with the instruction that it be used only at the beginning of a “word”. If so, we might conjecture that in other sections where there are “words” beginning with ④, such as {④c89} in the “text” section, they are references to the “balneological” section.

Furthermore, in the "balneological" section we rarely see the ubiquitous "word" {8am}; and therefore we rarely see the glyph {8} in slot 0. Again, it is as if for this section, the producer specified {8} in a different way from that for the other sections.

Scribes

Finally the same exercise, applied to the pages written by each major scribe, yields mixed results.

The ten most frequent "words" written by each of the four major scribes of the Voynich manuscript, as identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis; and for each "word", the corresponding slots in Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet". Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQSU9h

Here, we can detect the following differences between the scribes:

Next steps

From these relatively low-tech exercises, I have the impression that the division of the Voynich manuscript into thematic sections is the most important differentiation. In particular, the “balneological” section seems to stand alone. These results tend to reinforce my feeling that in any attempt at mapping from the Voynich text to natural languages, it is advisable to work with a single thematic section. My preference is the “herbal” section, which is the largest; and within that section, the pages written by scribe 1.

In previous articles on this platform, I expressed the view that the producer would have wished to give the scribes a simple set of instructions, whereby they could write the text with minimal supervision. Furthermore, such instructions had to yield a text in which, within nearly every “word”, the glyphs followed a relatively strict sequence, of the kind that Mary D'Imperio and Massimiliano Zattera observed.

As a working assumption, I conjectured that the producer provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages, together with a simple system for mapping letters to glyphs. A relatively undemanding rule could be as follows: take one word at a time, first transcribe the letters to glyphs, then re-order the glyphs in each "word" according to a "Voynich alphabet".

Zattera's "alphabet"

Zattera's "slot alphabet" describes a process for such a re-ordering. However, with Zattera's alphabet, the scribes would need to know where to place the "nomadic glyphs". For example, should a v101 glyph {8} be in slot 0, 7 or10? In Zattera’s alphabet, all three are permitted.

Zattera’s "slot alphabet". Glyphs which can be in multiple "slots" are marked in cells with solid borders. Graphics by author. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2oj1sYr.

Trying to step into the Voynich producer's shoes, I could imagine that he or she might define two or more "slot alphabets". Perhaps in one alphabet, {8} is always in slot 0; in the second, always in slot 7; in a third, always in slot 10.

We might see evidence of such multiplicity if we subdivide the manuscript in various ways. There are at least three such ways, as follows.

• “Language”. At Mary D’Imperio’s seminar in 1976, Captain Prescott Currier identified two “languages” in the Voynich manuscript. He called them “Language A” and “Language B”. Currier was clear that they were not different languages in the vernacular sense; simply that they had different (but overlapping) vocabularies. The downside of this concept is that Currier never defined the difference between A and B; he said only that it was statistical. Therefore, there is no objective algorithm by which, today, we can classify a Voynich page as A or B.

• “Section”. We are on stronger ground if we subdivide the manuscript by thematic sections, on the basis of the illustrations. Conventionally in Voynich research (and here I defer to René Zandbergen), we can recognise four major sections, which we can call “balneological”, “herbal”, “pharmaceutical” and “text”; and one small section, which we could call “cosmic”. The producer might have defined a "slot alphabet" for each section of the manuscript.

• Scribes. Another differentiation in the manuscript is between the hands of the various scribes. Here I acknowledge the work of Dr Lisa Fagin Davis, who in 2020 extended Currier’s earlier work and identified five individual scribes. Here we might conjecture that each scribe had his or her own “slot alphabet”.

Three ways to subdivide the Voynich manuscript: by "language" (after Prescott Currier); by thematic "section" (after René Zandbergen); and by scribe (after Dr. Lisa Fagin Davis). Author's analysis.

To test this hypothesis, we could invite Mr Zattera to re-run his program on Language A and B separately; on each of the themed sections; and on the pages written by each of the five scribes.

As a low-tech alternative to re-running Mr Zattera’s program: it occurred to me that we could subdivide the Voynich manuscript in the three ways proposed above; in each subdivision, select the most frequent “words” (say, the top five or ten); test each of these “words” for conformity with Zattera’s “slot alphabet”; and examine whether there is any version of the “slot alphabet” that best fits the subdivision.

"Languages"

Below are my results for the subdivision by “language”.

The ten most frequent "words" in the "Language A" and "Language B" pages of the Voynich manuscript, as defined by Currier. Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQLeDP.

Here we can see that in both “languages”, at least among the top ten “words”:

• the “nomadic” glyph {8} can be in slots 0, 7 or 10So, to my mind, this test yields no evidence that “Language A” and “Language B” have different alphabets.

• the “flexible” glyph {o} can be in slots 1 or 8

• the “flexible” glyphs {e} and {y} can be in slots 2 or 10.

"Sections

However, the same exercise on the thematic sections reveals a substantial differentiation in vocabulary and in conformity to the “slot alphabet”.

The ten most frequent "words" in the four major thematic sections of the Voynich manuscript; and the conformity of each "word" to Zattera's "slot alphabet". Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQSf8d.

Here we see that the “balneological” section has a distinctive vocabulary, in which the top ten “words” are dominated by “words” beginning with ④, and only two “words” are in common with the other three sections. This result suggests that in this section, either the precursor documents were in a different language, or the rules for transcribing letters to glyphs were in some sense unique. That is, the “balneological” section may have a different alphabet from the others.

It is as if the producer specifically allocated the glyph ④ to the “balneological” section, with the instruction that it be used only at the beginning of a “word”. If so, we might conjecture that in other sections where there are “words” beginning with ④, such as {④c89} in the “text” section, they are references to the “balneological” section.

Furthermore, in the "balneological" section we rarely see the ubiquitous "word" {8am}; and therefore we rarely see the glyph {8} in slot 0. Again, it is as if for this section, the producer specified {8} in a different way from that for the other sections.

Scribes

Finally the same exercise, applied to the pages written by each major scribe, yields mixed results.

The ten most frequent "words" written by each of the four major scribes of the Voynich manuscript, as identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis; and for each "word", the corresponding slots in Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet". Keyboard assignments are from author's v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQSU9h

Here, we can detect the following differences between the scribes:

• Scribes 2 and 3 used what we might call the “④ vocabulary”; and scribes 1 and 4 did not.On the whole, it does not seem that scribes 1, 2, 3 and 4 had different alphabets, or more precisely, different rules for ordering the glyphs within “words”.

• Scribes 1, 3 and 4 used the "word" {8am} extensively; this “word” requires the glyph {8} to be in slot 0. Scribe 2 used {8am} less frequently, and therefore had less occasion to place {8} in slot 0.

• All four scribes used the extremely common "word" {oe}, in which both {o} and {e} have two choices of slot.

Next steps

From these relatively low-tech exercises, I have the impression that the division of the Voynich manuscript into thematic sections is the most important differentiation. In particular, the “balneological” section seems to stand alone. These results tend to reinforce my feeling that in any attempt at mapping from the Voynich text to natural languages, it is advisable to work with a single thematic section. My preference is the “herbal” section, which is the largest; and within that section, the pages written by scribe 1.

Published on May 13, 2024 06:13

•

Tags:

d-imperio, lisa-fagin-davis, voynich, zattera

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 67 followers