Voynich Reconsidered: the Latin “qu”

In Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, 2024), and in previous articles on this platform, I explored the idea that the scribes of the Voynich manuscript had worked from precursor documents in medieval Latin. I conjectured that the producer had given the scribes a set of Latin documents, and a mapping from Latin letters to glyphs. As a simple assumption that conformed to Occam’s Razor, I supposed that the mapping had been one-to-one. In other words, I assumed that the scribes had mapped each Latin letter uniquely to a Voynich glyph. (Reasonable people may disagree.)

The question then arose: how would the Voynich scribes have dealt with the Latin bigram “qu”? In Latin as in most medieval and modern European languages, the letter “q” is almost invariably followed by the letter “u”. In fact, we could think of the bigram “qu” as a single letter.

The frequency of “q”

We may observe first that in Latin, “q” is not a very common letter. For example, in my copy of Dante Alighieri’s Monarchia, written in 1312-13, there are 111,691 characters excluding punctuation. The letter “q” (equivalently, the bigram “qu”) occurs 1,742 times; its frequency, relative to the character count, is 1.6 percent.

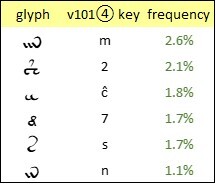

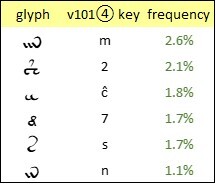

If the Voynich scribes mapped Latin letters to glyphs one-to-one, then any glyph which represents “q” should have an approximately similar frequency: say in the range 1 to 3 percent, with allowance for the natural divergences between one precursor document and another. Therefore, to my mind, the glyphs that are most likely to represent “q” are the following:

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: glyphs with frequencies between 1 and 3 percent. Author’s analysis.

If, as I suspect, {7} is a simply a handwriting variant of the far more frequent glyph {8}, then it should be excluded as a transcription of “q”. I am inclined to think that {s} also is improbable, since it occurs pervasively as a single-letter “word”. That seems to leave (2} and {ĉ} as the most probable candidates. (I write {ĉ} for the v101 glyph {C}, simply to avoid any confusion between upper and lower case. )

Separate “q” and “u”

If the scribes had mapped "q" and "u" separately, then I can think of two possibilities regarding the resultant glyphs:

If we now advance the hypothesis that {4o} is a transcription of “qu”: the downside is that the frequencies are not a very good match. In the v101④ transliteration, the glyph ④ has a frequency of 3.3 percent. This does not exclude the hypothesis: we could conjecture that the presumed precursor text of the Voynich manuscript had an unusually high incidence of “qu”.

As to whether there are any two glyphs that always co-occur within Voynich “words”: this is a more complex hypothesis. Testing it would require more programming skills than I possess. However, as a low-tech test, I would venture that we could at least investigate the bigrams starting with {2} or {ĉ}.

{2} and its companions

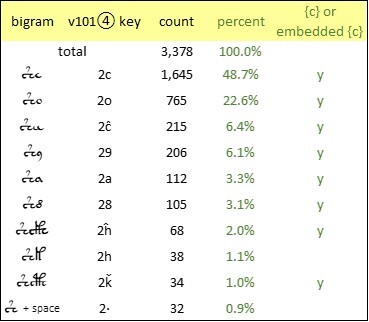

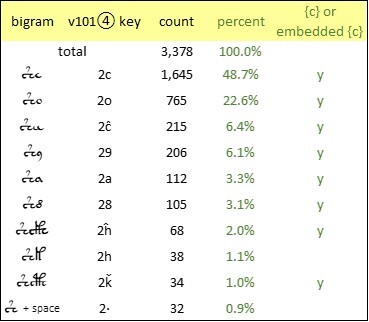

With regard to the glyph {2}, I found a remarkable and somewhat unexpected phenomenon. In my v101④ transliteration, I counted all the bigrams that started with {2}. In 48.7 percent of these bigrams, {2} was followed by {c}. But among the other glyphs that followed the {2}, there was a vast preponderance of glyphs that seemed to have an embedded {c}. That is, they contained the quill stroke for {c}, but added further quill strokes which, conventionally, are seen as resulting in another glyph. I calculated that of the bigrams that started with {2}, 97.1 percent followed the {2} either with a {c} or with an embedded {c}.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: the ten most frequent bigrams starting with {2}. Author’s analysis.

Accordingly, we might hypothesise that, for example, the sequence {2o} is not a bigram, but a trigram of the nature {2cↄ}, in which {ↄ} is a (so far) undefined glyph which is merged with the preceding {c}. If so, that would help explain the extremely high frequency of the glyph {o), by comparison with the most common letter in most European languages. Likewise, (29} might be a trigram which we could express as (2c,}, and {2a} might be expressed as {2c\}.

{ĉ} and its companions

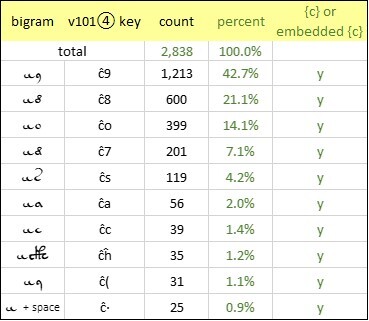

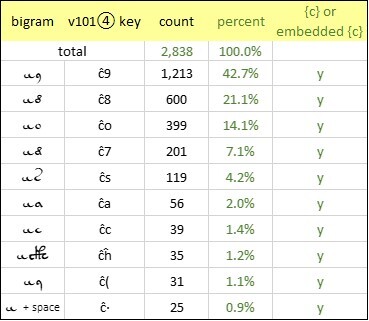

We see a similar phenomenon with the glyph {ĉ}. This glyph also has a favorite companion, namely {9}. In 42.7 percent of the bigrams starting with {c}, the next glyph (perhaps we should say: the next grapheme) is {9}. Furthermore, we see also here a proliferation of the “embedded” {c}. In 98.1 percent of the bigrams starting with {ĉ}, the next glyph or grapheme is written with an initial quill stroke that forms a {c}.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: the ten most frequent bigrams starting with {ĉ}. Author’s analysis.

Again, if {9} is sometimes not one glyph but two, that would help explain the egregiously high frequency of the {9} in comparison with common letters in European languages.

So, both with {2} and with {ĉ}, we have approximately the right frequency to represent the Latin “q”, and the possibility that the glyph has a constant companion, even if sometimes concealed, which could represent the Latin “u”.

Visual similarities

As an alternative to statistical analysis, we could consider visual similarities. Given that the Latin “qu” is effectively a single letter written as two, we might be tempted to look for a counterpart glyph with complex quill strokes, or a glyph that seems bifurcate in some way. That is, writing the glyph should require at least one lift of the quill between strokes.

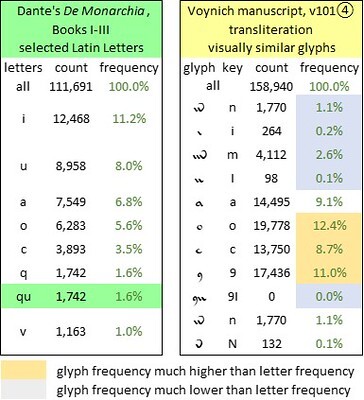

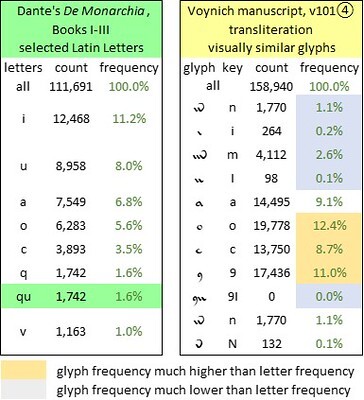

By way of a counterpoint: we should observe that several common Voynich glyphs seem to resemble Latin letters; and it is tempting to infer that they do indeed represent the respective letters. However, the frequencies are largely wrong. The following table juxtaposes the frequencies of the “Latin-looking” glyphs with those of the Latin letters that they resemble.

A selection of lower-case Latin letters for which visually similar glyphs exist in the Voynich manuscript; and the corresponding frequencies. Author's analysis.

With this reservation: to my mind, there are several glyphs which look as if they could have been mapped from bigrams. They include ④; {1}; {2} and its variants; and the “gallows” glyphs {f}, {g}, {h} and {k}. Their frequencies, in each of the main thematic sections of the manuscript, are summarised below.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration, main thematic sections: frequencies of selected glyphs with complex or bifurcate quill strokes. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pRK9H9

Here again, to my mind we see some possibilities that the glyphs {2} and {ĉ}, and possibly ④, could represent “qu”, both in terms of the complexity of the quill strokes and in terms of frequencies; also, that if the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from Latin precursors, that the rules of transcription could have been different from one thematic section to another.

Postscript

If the source documents were in natural languages other than Latin, the same analysis would be applicable; but the letter frequencies would change, and therefore the putative letter-to-glyph mapping would be different.

For example, we might select Dante's La Divina Commedia to represent medieval Italian, or more precisely, the medieval Tuscan which became modern Italian. In my copy, in which, following Adriano Cappelli, I abbreviated certain prefixes, the bigram "qu" accounts for just 0.8 percent of the overall letter count. In this case the glyphs that suggest the best mapping for "qu" would be different from those for Latin.

The question then arose: how would the Voynich scribes have dealt with the Latin bigram “qu”? In Latin as in most medieval and modern European languages, the letter “q” is almost invariably followed by the letter “u”. In fact, we could think of the bigram “qu” as a single letter.

The frequency of “q”

We may observe first that in Latin, “q” is not a very common letter. For example, in my copy of Dante Alighieri’s Monarchia, written in 1312-13, there are 111,691 characters excluding punctuation. The letter “q” (equivalently, the bigram “qu”) occurs 1,742 times; its frequency, relative to the character count, is 1.6 percent.

If the Voynich scribes mapped Latin letters to glyphs one-to-one, then any glyph which represents “q” should have an approximately similar frequency: say in the range 1 to 3 percent, with allowance for the natural divergences between one precursor document and another. Therefore, to my mind, the glyphs that are most likely to represent “q” are the following:

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: glyphs with frequencies between 1 and 3 percent. Author’s analysis.

If, as I suspect, {7} is a simply a handwriting variant of the far more frequent glyph {8}, then it should be excluded as a transcription of “q”. I am inclined to think that {s} also is improbable, since it occurs pervasively as a single-letter “word”. That seems to leave (2} and {ĉ} as the most probable candidates. (I write {ĉ} for the v101 glyph {C}, simply to avoid any confusion between upper and lower case. )

Separate “q” and “u”

If the scribes had mapped "q" and "u" separately, then I can think of two possibilities regarding the resultant glyphs:

• If the scribes retained the order of the letters within the Latin words, the two glyphs would always be adjacent to one another.With regard to the first possibility: in the v101 transliteration, there is only one glyph with a constant companion: that is the glyph {4), which in 96 percent of its occurrences is followed by {o}. Indeed, to my eye, the {4) and the {o} appear to be conjoined; and to my mind, {4o} is not two glyphs but one, which I have represented in my v101④ transliteration by the Unicode symbol ④.

• If the scribes re-ordered the glyphs after transcription, as Mary D’Imperio’s and Massimiliano Zattera’s work encourages us to believe, then the two glyphs would co-occur within Voynich “words”. They would not necessarily be adjacent.

If we now advance the hypothesis that {4o} is a transcription of “qu”: the downside is that the frequencies are not a very good match. In the v101④ transliteration, the glyph ④ has a frequency of 3.3 percent. This does not exclude the hypothesis: we could conjecture that the presumed precursor text of the Voynich manuscript had an unusually high incidence of “qu”.

As to whether there are any two glyphs that always co-occur within Voynich “words”: this is a more complex hypothesis. Testing it would require more programming skills than I possess. However, as a low-tech test, I would venture that we could at least investigate the bigrams starting with {2} or {ĉ}.

{2} and its companions

With regard to the glyph {2}, I found a remarkable and somewhat unexpected phenomenon. In my v101④ transliteration, I counted all the bigrams that started with {2}. In 48.7 percent of these bigrams, {2} was followed by {c}. But among the other glyphs that followed the {2}, there was a vast preponderance of glyphs that seemed to have an embedded {c}. That is, they contained the quill stroke for {c}, but added further quill strokes which, conventionally, are seen as resulting in another glyph. I calculated that of the bigrams that started with {2}, 97.1 percent followed the {2} either with a {c} or with an embedded {c}.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: the ten most frequent bigrams starting with {2}. Author’s analysis.

Accordingly, we might hypothesise that, for example, the sequence {2o} is not a bigram, but a trigram of the nature {2cↄ}, in which {ↄ} is a (so far) undefined glyph which is merged with the preceding {c}. If so, that would help explain the extremely high frequency of the glyph {o), by comparison with the most common letter in most European languages. Likewise, (29} might be a trigram which we could express as (2c,}, and {2a} might be expressed as {2c\}.

{ĉ} and its companions

We see a similar phenomenon with the glyph {ĉ}. This glyph also has a favorite companion, namely {9}. In 42.7 percent of the bigrams starting with {c}, the next glyph (perhaps we should say: the next grapheme) is {9}. Furthermore, we see also here a proliferation of the “embedded” {c}. In 98.1 percent of the bigrams starting with {ĉ}, the next glyph or grapheme is written with an initial quill stroke that forms a {c}.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration: the ten most frequent bigrams starting with {ĉ}. Author’s analysis.

Again, if {9} is sometimes not one glyph but two, that would help explain the egregiously high frequency of the {9} in comparison with common letters in European languages.

So, both with {2} and with {ĉ}, we have approximately the right frequency to represent the Latin “q”, and the possibility that the glyph has a constant companion, even if sometimes concealed, which could represent the Latin “u”.

Visual similarities

As an alternative to statistical analysis, we could consider visual similarities. Given that the Latin “qu” is effectively a single letter written as two, we might be tempted to look for a counterpart glyph with complex quill strokes, or a glyph that seems bifurcate in some way. That is, writing the glyph should require at least one lift of the quill between strokes.

By way of a counterpoint: we should observe that several common Voynich glyphs seem to resemble Latin letters; and it is tempting to infer that they do indeed represent the respective letters. However, the frequencies are largely wrong. The following table juxtaposes the frequencies of the “Latin-looking” glyphs with those of the Latin letters that they resemble.

A selection of lower-case Latin letters for which visually similar glyphs exist in the Voynich manuscript; and the corresponding frequencies. Author's analysis.

With this reservation: to my mind, there are several glyphs which look as if they could have been mapped from bigrams. They include ④; {1}; {2} and its variants; and the “gallows” glyphs {f}, {g}, {h} and {k}. Their frequencies, in each of the main thematic sections of the manuscript, are summarised below.

Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration, main thematic sections: frequencies of selected glyphs with complex or bifurcate quill strokes. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pRK9H9

Here again, to my mind we see some possibilities that the glyphs {2} and {ĉ}, and possibly ④, could represent “qu”, both in terms of the complexity of the quill strokes and in terms of frequencies; also, that if the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from Latin precursors, that the rules of transcription could have been different from one thematic section to another.

Postscript

If the source documents were in natural languages other than Latin, the same analysis would be applicable; but the letter frequencies would change, and therefore the putative letter-to-glyph mapping would be different.

For example, we might select Dante's La Divina Commedia to represent medieval Italian, or more precisely, the medieval Tuscan which became modern Italian. In my copy, in which, following Adriano Cappelli, I abbreviated certain prefixes, the bigram "qu" accounts for just 0.8 percent of the overall letter count. In this case the glyphs that suggest the best mapping for "qu" would be different from those for Latin.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers