Peter Rollins's Blog, page 30

January 8, 2014

Hocus Pocus: The Pledge, Turn, and Prestige of Faith

Join my friends and I on March 14th for a unique day of talks, workshops, reflections, music, magic and general mayhem based on the themes of my new book The Divine Magician. This event will be of interest to those interested in the theory and practice of Future Church (Pastors, youth leaders, and students). We’ll be exploring innovative and subversive ways of rethinking the role of church life, ones that question old orthodoxies, open up new paths that embrace doubt, complexity and ambiguity and which question age old distinctions between theism and atheism, faith and the faithless, spirituality and materiality.

Then, in the evening, we’ll all descend onto the Monkish Brewing Company where there’ll be a live Homebrewed Christianity event on the themes of the conference, a closing party with live music and close-up magic and the launch of a speciality Lenten beer lovingly crafted by New Testament scholar turned Brew Master Henry Nguyen (the first one’s on us).

And, as if that wasn’t enough, anyone who’s around the night before can come out for pre-game drinks.

There are only 50 places for the event and the cost doesn’t include dinner.

Guests

I’m excited to announce that the now infamous “pastor-turned-atheist-for-a-year” will be joining us for the day. Ryan Bell recently shot to international attention when he started a personal thought-experiment in which he decided to live as an atheist for a year. Within a week he’d lost two jobs and was bailed out of financial ruin (at least temporarily) by supporters from outside the theistic fold. Ryan is a personal friend and I’m grateful that he’s taken time out to speak at our intimate gathering.

Tripp Fuller is well known for standing at the helm of the inimitable Homebrewed Christianity podcast. This much loved show has gained an international reputation for encouraging critical and creative thinking amongst those interested in theological theory and practice. In addition to this he’s currently finishing his PhD in the Philosophy of Religion and Theology at Claremont Graduate University.

One-time evangelical pastor Tad DeLay left his community and turned to critical theory to explore the nature of religion, faith and future church. I’m excited for his input in the day as he brings a wealth of understanding pulled from the branches of psychoanysis, theology and philosophy. He’s also a musician and is completing a PhD at Claremont Graduate University. He holds an MA in Theology and Biblical Studies from Fuller Theological Seminary and a BA in psychology.

…more to be announced…

If you’d like to keep up with updates, or ask any questions, join the Facebook page

To get a ticket click here

Hocus Pocus, Los Angles, CA

Join my friends and I for a unique day of talks, workshops, reflections, music, magic and general mayhem based on the themes of my new book The Divine Magician. This event will be of interest to those interested in the theory and practice of Future Church (Pastors, youth leaders, and students). We’ll be exploring innovative and subversive ways of rethinking the role of church life, ones that question old orthodoxies, open up new paths that embrace doubt, complexity and ambiguity and which question age old distinctions between theism and atheism, faith and the faithless, spirituality and materiality.

Then, in the evening, we’ll all descend onto the Monkish Brewing Company where there’ll be a live Homebrewed Christianity event on the themes of the conference, a closing party with live music and close-up magic and the launch of a speciality Lenten beer lovingly crafted by New Testament scholar turned Brew Master Henry Nguyen (the first one’s on us).

And, as if that wasn’t enough, anyone who’s around the night before can come out for pre-game drinks.

There are only 50 places for the event and the cost doesn’t include dinner.

Guests

I’m excited to announce that the now infamous “pastor-turned-atheist-for-a-year” will be joining us for the day. Ryan Bell recently shot to international attention when he started a personal thought-experiment in which he decided to live as an atheist for a year. Within a week he’d lost two jobs and was bailed out of financial ruin (at least temporarily) by supporters from outside the theistic fold. Ryan is a personal friend and I’m grateful that he’s taken time out to speak at our intimate gathering.

Tripp Fuller is well known for standing at the helm of the inimitable Homebrewed Christianity podcast. This much loved show has gained an international reputation for encouraging critical and creative thinking amongst those interested in theological theory and practice. In addition to this he’s currently finishing his PhD in the Philosophy of Religion and Theology at Claremont Graduate University.

One-time evangelical pastor Tad DeLay left his community and turned to critical theory to explore the nature of religion, faith and future church. I’m excited for his input in the day as he brings a wealth of understanding pulled from the branches of psychoanysis, theology and philosophy. He’s also a musician and is completing a PhD at Claremont Graduate University. He holds an MA in Theology and Biblical Studies from Fuller Theological Seminary and a BA in psychology.

…more to be announced…

If you’d like to keep up with updates, or ask any questions, join the Facebook page

To get a ticket click here

Critical Theory, Grand Rapids, MI

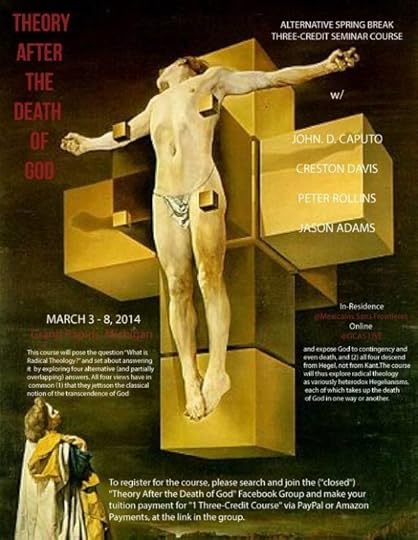

This course will pose the question “What is Radical Theology?” and set about answering it by exploring four alternative (and partially overlapping) answers. All four views have in common (1) that they jettison the classical notion of the transcendence God and expose God to contingency and even death, and (2) all four descend from Hegel, not from Kant. The course would thus explore radical theology as variously heterodox Hegelianisms, each of which takes up the death of God in one way or another.

For more information, or to register, click here

December 24, 2013

Revolution, Minneapolis, MN

December 10, 2013

Pyrotheology and the political

Being born and raised in East Belfast, Northern Ireland, my work developed from the context of The Troubles. “The Troubles” refers to the systematic violence that began in the late 60’s and ended with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. During that time 3,500 people lost their lives, which, considering the population of Northern Ireland, ensured that everyone was directly impacted by the devastation. On top of that, businesses were destroyed, people maimed, bombs thrown and riots became something of a constant backdrop to daily life. During this period almost 50 peace walls were erected, spanning over 20 miles of land (with more being installed after the Good Friday Agreement), and many areas became enclaves where the police couldn’t enter without military support.

The Troubles itself involved an explosive cocktail of religion, politics, class issues and questions concerning ethnic identity. But rather than thinking of this as a conflict perhaps it is better to think of it as the refusal to have conflict.

The Troubles, like all wars, was partly the result of a failure to embrace conflict. By this I mean that wars are generally started by those who wish to attempt to destroy their enemy rather than enter into the difficulty of real engagement with them. We’d rather destroy the other than really listen to what they have to say and do the difficult work of sitting in the same room, hashing out the relevant issues. War can then be seen as the failure of politics, which is the arena in which true conflict should play out.

While my work was partly a response to all this, it was also connected to the way that The Troubles themselves became a type of reflection of my own inner troubles. At a personal level the same walls I witnessed all around my city also reflected my more personal ones. The projection I saw happening so explicitly at a social level seemed to speak of a reality that I tried to deny was within me. Belfast thus became a type of psychic landscape, revealing to me my own more subtle struggles. The personal and the political thus began reflect each other for me. They spoke to each other and started to appear intimately intertwined.

It is partly because of this that I came to believe the work some of us were engaged in there would be able to speak beyond Belfast. If a doctor is training students to identify cancer, she must first show the students extreme forms so that they might be able to identify less extreme, less developed forms. In this way they learn what to look out for before the tumour gets out of control. In the same the work of pyrotheology might be able to identify less extreme forms of religious/political/cultural exclusion and violence because it grew out of a context were they were so overt.

The aim of pyrotheology is not to avoid conflict, but rather to affirm creat a space for it. There are real and serious issues to be addressed in every culture, and the strategies of hawk-like war or liberal conflict avoidance are rarely the answer. Rather gritty, dirty salons are required were drinks can be slammed onto tables, obscenities shouted and tears shed. Spaces were the only real non-negotiable is a commitment to returning again and again to the same space and the same people. To hash things out, to be challenged and to perhaps discover that the other has a perspective that might change you.

The point of embracing unknowing, interrogating assumptions and facing personal issues (the bread and butter of pyrotheology) is to facilitate a better form of life that is not only more enjoyable and enriching at a personal level, but also one that provides the basis of more healthy and effective political engagement.

Pyrotheology, baptised as it was in a world full of violence, has always had a political edge and outworking. But it isn’t one that falls along the usual political lines. It is one that comes from seeing first-hand a city go through, come out of, and still struggle with, a world of deep antagonism. It is one that has learned first hand from unsung peace makers. And it is one that embraces the messiness that comes from true engagement with the other.

It’s my hope that some of those involved with exploring, developing and critically engaging with this thinking might be able to help bring some of these elements to the surface in the coming years.

December 4, 2013

Entering into the Question

I’ve recently returned to a relatively unknown book I wrote back in 2008 called The Fidelity of Betrayal. It fell totally beneath the radar when it first came out and, truth be told, I largely forgot about it. In addition to that, the content proved a little much for many of the places I spoke and often wasn’t sold. Basically it just seemed to get eclipsed by peoples interest in How (Not) to Speak of God. However there are some people I respect who view it as my best book to date and have been encouraging me to get some of its ideas out there. So I’m going to offer some free sections from it over the coming weeks. Consider it an early Christmas present for being on the naughty list.

This section touches on the idea of faith as entering into a type of ongoing debate with the deepest questions that haunt us.

December 3, 2013

A Supernatural Beyond Sacred and Secular

The word “supernatural” is almost universally tied to a religious worldview. Regardless of whether one affirms the supernatural or denies it, the term seems inextricably and necessarily connected with some belief in higher powers. Interestingly however this religious definition of the supernatural is almost concerned only with the purely natural realm. For instance, miracles are ascribed to physical occurrences like a resuscitation of someone who was dead or the feeding of a vast crowd with a few loaves of bread and a handful of fish.

In contrast, there is a different way of approaching the supernatural: one that doesn’t see it as describing a change in the natural realm, but rather as describing a change in how we interact with the natural realm (hence super-natural). This is a view of the supernatural that can be affirmed by the theist and the atheist alike. Here a miracle isn’t directly encountered in being able to raise someone from the dead or in feeding a vast crowd of strangers with crumbs (amazing as these acts would be). Rather it is indirectly glimpsed in that change in our life when we judge a person’s life worthy of being brought back to life, or when discover a compassion that makes us believe a crowd of total strangers should be fed. It is then testified to in that moment when we come to believe that life has a depth dimension worth living for. A depth dimension worth dying for.

This is something I explore in my (almost completely unknown) book The Fidelity of Betrayal.

November 21, 2013

Burning Down, Huntington, IN

What change needs to take place in ourselves and our structures for our communities to be known for their hospitality and extraordinary love?

Van Gogh painted “The Starry Night” from his recollection of the night landscape outside his asylum cell. He bathed the landscape in yellow – his color for the presence of the Divine. And yet one place remained candidly dark – the church at the center of his work.

November 17, 2013

A Miracle Without Miracle

Here’s a little parable from The Orthodox Heretic. For the next couple of weeks you can listen to an audio version of this by clicking here and pressing the play button beside the name “Miracle Without Miracle”.

After Jesus had descended from the Mount of Olives he came across a man who had been blind from birth. And his disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he cannot see?”

Jesus answered, “It was not that this man sinned, or his parents, but that the works of God might be displayed in him.. We must carry out the works of him who sent me while it is day for night is approaching, when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.”

Having said these things, he spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva. Then he anointed the man’s eyes with the mud and said to him, “My friend, go, wash in the pool of Siloam.” So he went and washed and returned in jubilation shouting, “I can see, I can see!”

The neighbors and those who knew him as a beggar began to grumble saying, “Has this man lost his mind, for he was born blind.” Some said, “It is the same man who was blind.” Others said, “No, it is not, but he is like him.” In response to this grumbling, the old man kept repeating, “I am the same man. Jesus anointed my eyes and said, ‘Go to Siloam and wash.’ So I went and washed and now can see everything.”

To ascertain what had happened they brought him to the Pharisees. “Give glory to God,” they said. “We know that this man Jesus is a sinner.” But the old man answered, “Whether or not he is a sinner I do not know. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see.”

But the Pharisees began to laugh. “Old man, meeting Jesus has caused you to lose your mind, you had to be carried into this room by friends, you still stumble and fall like a fool, you are as blind today as the day you were born”.

“That may be true,” replied the old man with a long deep smile, “as I have told you before. All I know is that yesterday I was blind but today, today I can see”.

November 15, 2013

New Atheism and the Death of God

Over the coming weeks I wish to write a few reflections concerning the discussion that took place between myself and Lawrence Krauss. This will be used as a means of getting to the heart of some critiques I have of the New Atheism movement as a whole. The main one mimicking the critique that psychoanalysis has with regards to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (namely that the latter doesn’t deal with the unconscious). Something that become evident in the debate with Krauss when he showed that he simply didn’t understand what is meant by the “death of God” and when he couldn’t fathom the way that fundamentalism was, structurally speaking, not an intellectual position but a means of protection against a trauma.

Anyway, for now I simply wish to publish a discussion Krauss and I had that was originally for The Guardian in Australia (but which wasn’t published because of the different lengths of response). The question that The Guardian asked us to talk about was: Have the new atheists won the battle of ideas by proving that religion isn’t true?

PR: This question might help us get to the heart of my problem with “New Atheism” (a term that is as problematic as “New Religion”). For the problem is not that it has gone too far in its critique, but rather that it hasn’t gone anywhere far enough.

I think the first great critic of the approach summed up in “New Atheism” was the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who, at the twilight of the nineteenth century wrote a scathing parable attacking the cultural elite who took joy in proclaiming the end of religion.

The story goes that a madman finds himself in a marketplace seeking God. Because he’s surrounded by enlightened nonbelievers he’s ridiculed for his pursuit. But then the madman tells them that the God he seeks is dead and that everyone in the marketplace has killed him. At this point in the parable we find an interesting antagonism, for the madman is telling those who don’t believe what they seem to already know, namely that God is dead as an anchoring point in their lives, that God is an idea whose time has passed: But he is precisely accusing them of not knowing it.

He goes on to say that, like a lightening strike in which we have not yet heard the crash of thunder, the impact of this insight has not yet hit them. They walk around feeling great about their “insight” without actually feeling the mad and horrific consequences of it. Hence, in a different passage, Nietzsche refers to a myth about the shadow of the Buddha remaining on a cave wall after the Buddha had died, commenting that the shadow of God still remains after the death of God and that the task set before us is the removal of the shadow.

In simple terms we can understand what this means by reflecting upon how none of us really believe that having a bigger house or better car will make us happy, and yet we continue to materially act as if it will. Or we might know that a loved one has died, yet we protect ourselves from the grief of that knowledge through a type of security blanket: such as keeping the room of our beloved exactly as it was.

The bigger house/better car/preserved room act as a fetish in the psychoanalytic sense of the term in that they act as objects that we know are not magical yet treat as if they are. A fetish object does not hide us from some kind of knowledge, but protects us from experiencing the psychological impact of the knowledge we already have. Just like an actual security blanket carried by a child doesn’t prevent them from knowing that they are in a room full of people, but rather protects them for the impact of that knowledge.

The critique then that “New Religion” offers against “New atheism” is a precise one… it has not felt the impact of its own claims, indeed it hides from the horror and madness of its own insights through its often bourgeois, detached elitism.

New Religion admittedly doesn’t sound like a very attractive proposition, for it is the place that one enacts this terrifying insight in a bodily way (through music, poetry, ritual and liturgy). It is for the mad men and women, like Nietzsche, who are ready to hear the crash of the thunder in their lives.

My larger argument is that this experience of the “death of God,” far from being against the insight of faith, is its subversive, scandalous heart.

That the event one wishes to experience in the New Religion’s “church” is precisely that cry, “my God, my God why have you forsaken me.”

This is not an intellectual atheism, but an existential one. It is an atheism that is felt at the core of our being (an experience which is open to those who are, intellectual speaking, theists, atheists and agnostics).

However far from being depressing, it is in confronting this experience that leads to a fuller and more enriching life.

So the argument of New Religion is not that New atheists have gone too far by proving religion isn’t true in the marketplace of ideas, but that they’ve failed to go all the way.

LK: To the extent that I understand your point, I am a bit surprised. Why would one want to replace an old religion that doesn’t work with a new one that relies on angst? Moreover, at least where I live, the old religion is quite alive even if it is not well in the first world (in the developing world things are quite different. I do agree with you that it is experiencing slow death throes of realization that god simply doesn’t cut it anymore, but the response here is largely to retrench, to fight anything that might further god’s demise, and that fight can be extremely dangerous, and that fight is what many of the new atheists are trying to address. I can’t speak for others, but from my point of view, there are two messages: (1) hey, lighten up, this stuff is as silly as sex or politics, let’s treat it that way and (2) the real universe is so amazing that we shouldn’t feel the loss of god is a loss, it is a gain, it opens us up to more wonder and awe.

PR: As a brief aside, the point I’m making is not that we need to replace the old religion with a new one but rather to discover the new that exists as a potential within the old religion. In other words, to draw out a liberating kernel operating within the actually existing religion, one that will crack it open like new wine in an old wineskin. While this might seem like splitting hairs the point is an important one. For I would argue that the most effective tools for ridding the world of reactionary religion are found within it.

I will however spend my response reflecting on your concerns over the idea of having a religion that “relies on angst.” This is where I must turn to Kierkegaard and respond that I’m not trying to create angst but rather draw out the way in which we are already full of angst and show how the best way of working through this is in facing it and tarrying with it.

There are broadly two ways to cope with our angst: one involves hiding it/projecting it. The other involves making peace with it.

For Kierkegaard, the problem with angst was that it lurked within both everyday happiness and sadness. For him one could be happy and yet still be full of angst. Something we witness in the average nightclub, were one can’t help wondering what would happen if the lights went up and the music went down. Amidst all the pleasure it’s hard not to feel that the lights and the silence, combined with the awkward moment of looking each other in the eyes, would uncover in many an underlying sadness that didn’t just lie beneath their pleasure, but actually motivated their pursuit of it.

But in the same way that angst is deeper than both happiness and sadness, he argued that so too is joy. One can have joy even when facing difficult and sorrowful times. The point of the “New Religion” is to create spaces were people can encounter their angst, not so that they become enslaved by it, but so that they are freed from it just as talking about ones pain doesn’t strengthen it but helps to rob it of its sting.

In terms of the retrenchment you speak about in religion we simply diverge on our interpretation of it. The re-entrenchment of religion as seen in fundamentalism would, to me, signal not a security but precisely an insecurity. For instance, if I say to a friend that I think her partner is having an affair and she kicks me out of the house, telling me that she never wants to speak to me again, that is not evidence that she disagrees with me, but rather that she agrees with me but doesn’t want to directly confront her agreement. If what I said was something she didn’t know in some way her reaction would more likely be mere shock. The violent response is evidence of her own inability to face what she already suspects.

Within the religious world Fundamentalism is more often than not the externalization of an internal crisis. And here, once more, I would say that the most dangerous thing for these communities in crisis is not the position of the new atheist, but of those who attack from within (the “heretic” rather than the “infidel”).

You finish with two points. The first is that religion, like politics and sex, is silly and the second being that universe is amazing. I’m not sure I see why the first is necessarily silly while the second is not. Those who are depressed generally can’t place any value on anything while those who embrace life find it all incredible. In theological language, the latter experience a depth dimension in existence.

The majority of people who seek therapy go precisely because their desire is not functioning properly and everything seems pointless. The point of the “New Religion” is to help people face their angst, embrace life in the midst of unknowing and, in so doing, get themselves to the point were they can take seriously all of life.

What opens us up to awe and wonder is not a universe any more than a god: it is love. For those who do not love, the universe is experienced as meaningless even if they believe it is meaningful. While for those who love, the universe is experienced as saturated with meaning even if they believe it is not.

LK: Firstly, I agree there are seeds within the old religion to liberate people, and one can exploit some of the successful tools of religion, ritual, community etc. and we need to replace those positive aspects of religion with other sources when we get rid of it. Secondly, you misunderstand me. I agree the retrenchment is due to insecurity. However I don’t see that embracing that insecurity and that entrenchment will help. I see that ridiculing it will help. Thirdly, I am in awe of the universe, but I also think it is meaningless. Fourthly, the doctrines of religion are silly by any standard I can conceive. Moreover, taking ourselves too seriously is part of the problem, not part of the solution.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers