Peter Rollins's Blog, page 33

June 19, 2013

Give me that Duck: On the Law and Idolatry

My friend Casey recently sent me the story of a wealthy Judge who went on holiday in Ireland and ended up duck hunting. Half way through the day he shot a bird out of the air and it dropped into a farmers field a few hundred yards away.

As the Judge began to climb over the fence, an old farmer called Seamus drove up on his tractor and saw him clambering over the fence,

“What would you be doing there,” asked Seamus

“I just shot a duck and it fell into this field, I’m going to retrieve it.”

“Well now, this here is my property, and that would be trespassing.”

“Be careful,” shouted the Judge, “I’m a powerful man and I’ll make your life hell if you don’t let me get that duck”.

Seamus considered what he said replied,

“Apparently, you don’t know how we do things in these here parts. We settle disagreements like this with the Three Kick Rule.”

“What’s the Three Kick Rule?” asked the Judge

“Well, first I kick you three times and then you kick me three times, and so on, back and forth until someone gives up.”

The Judge looked at Seamus and decided that he could easily take the old man on.

“OK,” he said, “lets do this”

So Seamus slowly got down from the tractor, walked up to the Judge and did a few stretching exercises.

Then he planted his first kick square into the Judges groin, dropping him to the ground.

The second kick was to the side of the head and almost knocked him out.

The Judge was flat on his back and in agony, when the farmer’s third kick to the abdomen nearly caused him to throw up. But he kept his resolve, knowing that his turn was coming up next.

The Judge summoned every bit of strength and managed to get to back his feet,

“Okay, now it’s my turn.”

But the old farmer simply smiled and said,

“Naw, I give up. You can have the duck!”

What we see here is the way that a prohibition (the Law) functions to make the Judge ever more attached to the duck. The prohibition effectively creates an excessive attachment to the duck that transforms it into an invaluable object (the Idol).

Here the duck is turned into a type of sacred-object for the Judge, an object that he must possess. An excessive attachment is formed that means the Judge is willing to go through ridiculous trials in order to gain it.

It is only when the prohibition is removed that he is confronted with the unreasonable nature of his stubborn attachment.

This removal of the Law and the corresponding destruction of the Idol is what I take to be central to the Christ event and thus the mission of communities attempting to be faithful to that event. It is this theme that has informed my most recent work body of work, namely Insurrection, The Idolatry of God and my forthcoming The Divine Magician.

June 18, 2013

The Meeting, Brooklyn, NY

Ikon gathering… for more information click here

June 17, 2013

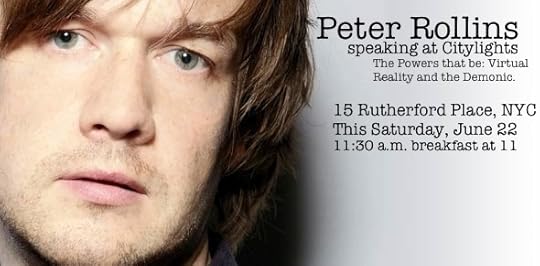

Virtual Reality, New York, NY

June 12, 2013

Playing With Fire Tour, Australia

TBC, Sydney, AU

I will be speaking at various events. More information to follow.

June 6, 2013

Broken Liturgy, Philadelphia, PA

Title: Church Undone

Location: First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia

Doors: 7:30pm

Event: 8:00pm

Cost: $10

June 5, 2013

We Sleep in Separate Rooms

I recently talked to a friend who told me that she was visiting her conservative religious family for a birthday and brought her partner for the weekend. Over the few days they slept separate rooms.

The question that immediately came to mind was ‘why?’ Who was it that didn’t think they shared a bed back home?

It couldn’t be for the parents or siblings because they were perfectly aware that my friend was an adult with her own home and in a long term relationship. And it was unlikely an act designed to protect God from the knowledge for the parents believe in an omniscient being. This was not then a direct act of deception to keep the knowledge from their family (we don’t sleep together) but a pretense (lets all pretend we don’t sleep together).

What we see here in action is what Lacan called the instantiation of the ‘Big Other’. The Big Other is a virtual reality (see this post for a description of the virtual) that is not actually believed in, but which informs our actions none-the-less (not existing, but insisting). The Big Other, in the example above, functioned as a non-existant subject that was oblivious to what was going on, a subject who the whole family had to keep in the dark about the facts.

In this way the Big Other prevented an unpleasant confrontation in the family. It was not that an antagonism within the family did not exist, but rather that everyone was acting as if it did not exist. By doing this a certain level of superficial relationship was able to be sustained (which suited my friend, who didn’t want some big argument).

Had people been confronted with at what they already know then the obvious differences that exist concerning attitudes toward religion, sex and morality would have been brought to the light of day. While this can no doubt be traumatic it is also what is necessary in the journey towards healthy conflict, deeper discusion and ultimately healthier relationships.

June 4, 2013

The objects We Desire and The Object-Cause of Our Desire

Psychoanalysis helps us to isolate two types of desirable things.

The first are objects. Simply put we find ourselves wanting certain things everyday, from when we get up to when we go to bed. Yet, if that thing is not available (or if we achieve it), we move onto something else. We might be angry or frustrated if we don’t get what we want, or we might be disappointed if we do. But the mechanism of desire remains unaffected. For instance, if a shop does not sell the type of sandwich we want we generally shrug our shoulders and decide on a different one.

In contrast there are object-causes of our desire. An object-cause is something that we not only desire, but which fuels our desire.

When we cannot have an object that we desire we move on without the mechanism of desire itself being affected. But when we lose our object-cause of desire we not only lose something that we want, but the very mechanism of desire is stalled.

Objects give us a certain level of pleasure, but an object-cause gives us jouissance. Jouissance being an excessive pleasure that is also experienced as pain.

Objects evoke our effort, but an object-cause scales the walls of our rationality and colonises our entire being.

Wars are won and lost over an object-cause, great literature is written adventures undertaken, lives judged worth living and kingdoms shaken.

The more we are taken in by a desire for jouissance the more a slave we are to an object-cause, whether that is a person, a project or an act.

June 2, 2013

You Are Responsible For Nothing

The famous philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote that we are “condemned to freedom”. For Sartre this meant that we are responsible beings. However we are not merely responsible for the decisions we make. In addition to this he drew out how we are also responsible for the decisions we postpone or fail to act on.

This means that we are not only responsible for what we do, but also for what we don’t do. Like a poker player in the middle of a tournament, even doing nothing is an act that will help decide the direction of the game. In this way we are constantly waging on our existence. Every move, and every failure to move, closes down an infinite range of possible worlds while opening up an entirely new range.

There is then no way to escape the feeling of regret except through fully embracing this experience of freedom. For if we don’t act on something we can regret not doing so, if we delay an act we can regret not acting sooner and if we act straight away we can regret that too. Decide on something, or not, act or don’t, speak or stay silent: we are responsible for them all.

For Sartre it is common for us to try and escape the weight of this responsibility. In describing how this happens he once related a small incident he witnessed while watching a couple sitting across from one another. As he glanced over he noticed the man reach across the table and take hold of the woman’s hand (a sign of his desires). In return the woman neither pulled her hand away (that would send a clear sign that she was not interested in his advances), nor did she grip his hand (which would have signaled her acceptance of the advance). Instead she allowed her hand to lie limp in his.

For Sartre this little moment can help us understand what the attempt to abdicate our responsibility looks like. He called this desire to become passive passengers in life “bad faith.” Bad faith being the attempt to flee our responsibility in the hope that we might not have to bare the yoke of our freedom.

Yet Sartre’s point is that this attempt to flee freedom is just another manifestation of freedom. It is simply a futile attempt to deny it.

Instead of the impotent and impossible attempt to flee our freedom Sartre encouraged us to face it, embrace it and make resolute decisions in light of it.

The choice for him was not between taking responsibility or not, but rather between acknowledging our inherent responsibility or attempting to deny it.

So what do our current actions or inactions say about our relation to freedom? And what might we do differently if we were to fully embrace our responsibility and make decisions in the full knowledge that there are no guarantees and no way of going in every direction we would like?

May 30, 2013

Are You a Protestant Muslim or a Catholic Muslim?

The title of this post relates to a (probably apocryphal) story from Northern Ireland in which a group of young lads stop a man who is walking down the street and asked him in a threatening way, “are you a Protestant or a Catholic?”

The man responds by pointing out that he is actually from Iran and is in fact a Muslim.

“That’s all very well,” replies one of the youths, “but are you a protestant Muslim or a Catholic Muslim?”

In Northern Ireland the terms “Protestant” and “Catholic” became markers of fixed political and tribal identity. Something the joke plays on in bringing to light how we can think that our issues are the same as those faced by others in the rest of the world.

This can also be seen in the story of an Indian man coming to Belfast to visit friends. While in a bar one night he strikes up a conversation with a local who asks him where he’s from.

“I’m from Delhi,” replies the man

In response the local leans over and whispers in his ear,

“Watch yourself mate, round here we call it Londondelhi’

The joke plays on the fact that there is a city in Northern Ireland that is either called “Derry” or “Londonderry” depending upon your political stance. One of the ways one can to work out whether you are a friend or an enemy is to find out which you call it.

In typical Northern Irish humor the joke is on us. Each of the stories arose to remind us how easy it is to think that the political situation we are dealing with is one that the rest of the world is involved with.

While it is true that the underlying dynamics and antagonisms are the same (scapegoating, oppressors, oppressed, structural injustice etc.) the actual way that these play out depends upon a rich matrix of historical factors unique to a given situation.

Indeed when people from outside Northern Ireland come in to try and help with sectarianism the results are often embarrassing at best and damaging at worst. I remember one particularly bad example when an Australian activist came over with thousands of bumper stickers that read, “Jesus: Friend of sinners, drunkards and Republicans.” A sticker that was problematic on so many levels (the word “Republican” broadly refers to someone who is prepared to take up arms to fight for a united Ireland, as opposed to a Loyalist who is prepared to take up arms to keep the North a part of the UK).

It generally takes people who have grown up in a society, who know the situation and who have a respect borne of growing up there to make real change happen.

Because of this it might seem that “outsiders” to our struggles are not needed, however the genuine multicultural experience remains an important one. For in it we first look at the other through our eyes and judge them, but then we glimpse how we might look through their eyes and judge ourselves.

It thus not only helps us see that other people are dealing with different issues, but can also help us to gain some new perspectives on our own.

So instead of making people from a different place feel like the Iranian visiting Belfast in the opening story perhaps the task is to see the other as coming from a different place that might expose something important about our own place, if only we can really listen to them.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers