Peter Rollins's Blog, page 31

November 6, 2013

The Third Mile: A Faithful Betrayal of the Text

A few months ago we created a mini sound studio in my house and recorded an audio version of The Orthodox Heretic. After listening to the finished product we felt that a little music was needed and so we contacted the artist Dubh to provide some ambient dubstep. If you click here you’ll find a free audio version of the short parable below. If you like it there are another thirty-two for you!

One day a small group of disciples who had embraced the way of Jesus early in his ministry heard him preaching by the side of a dusty road. As they crowded round they heard Jesus say,

“The law requires that you carry a pack for one mile, but I say carry it freely for two.”

The disciples were deeply impressed by these words, for at that time a Roman soldier had the legal right to demand that a citizen carry his pack for a mile as a service to the Empire. This teaching not only allowed the disciples to turn this oppressive law into an opportunity to demonstrate kingdom values, but also presented them with an opportunity to suffer in some small way for their faith.

As it was common for soldiers to evoke this law, the small band of believers soon developed a reputation for their actions. Roman soldiers would often hope that the citizens they asked to carry their packs would be among these disciples, and often a small bond of friendship would develop between a soldier and these followers of the Way.

After a year had passed this custom had become so established in the group that it became a defining characteristic of their shared life. The leaders would frequently refer to the teaching of Jesus and emphasize the need to carry a pack of the Roman soldier for two miles as a sign of one’s faith and commitment to God.

It so happened that Jesus heard about this community’s work, and, on his way to Jerusalem, took time to visit them. The leaders eagerly gathered all the members of the group to hear what Jesus would say. Once everyone had gathered, Jesus addressed them:

“Dear brothers and sisters, you are faithful and honest, but I have come to you with a second message, for you failed to understand the first. Your law says that you must carry a pack for two miles. My law says, ‘carry it for three.’”

Comments on the book,

“I remember driving around Belfast with Pete, sitting in the front seat listening to him tell these parables—thinking, ‘Everybody needs to hear these.’ Well now you can!”

—Rob Bell

Rollins has already established himself as a major voice and an astute, generative force within the emergence Christianity. The Orthodox Heretic is his most accessible and engaging work to date.”

—Phyllis Tickle

November 5, 2013

For the haunted houses that we are

Building on the success of the Idolatry of God event last year I’m running a second event called Holy Ghosts. This isn’t a retreat, lecture series or conference, but a curated festival of ideas.

It was Charles Dickens who, in A Christmas Carol, showed us how ghosts appear during those times when we’ve become entombed in our own world and cut off from others. Whether they be the ghosts of those we have loved and lost or the specters of inner doubt and unknowing, we are all haunted houses, yet most of us are afraid of meeting the uninvited apparitions that drift quietly through the corridors of our mind. But these messengers carry a word that we need to hear, a word that can not only open us up to new life, but transform the closed communities we find ourselves in.

With this in mind I will be journeying with forty people through the haunted houses of their lives and communities, exploring the liberating potential of these phantoms that float through the ruins of our past, that haunt the constructions of our present, and that spook our carefully planned visions for the future.

This ghost train-like event will weave its way through a maze of live music, transformance art, story telling, haunted houses, movies, talks and a little whisky (for spirits of a different kind).

If you’d like more information, or to book a ticket, click here

November 2, 2013

Is Fundamentalism a Problem or the Solution to a problem: A debate with Lawrence Krauss

Recently I engaged in a debate with Lawrence Krauss at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas under the title “New Religion vs. New Atheism,” (terms that neither of us felt comfortable with). My primary interest in this debate was to begin to test whether some of the tools I use when working in religious circles to break open fundamentalism might be of use in the context of New Atheism. The video will probably appear at some point, but for now I’ll give you the text of the argument I gave in my opening address (this differs a little from what I actually said as this is slightly shortened and I was extrapolating from notes on the day). I should also say that Krauss was bemused by my approach and felt that my arguments below were an exercise in “empty talk.”

Introduction

I’m not here to beat Lawrence in some debate or win cheap points. Nor am I here to build an alternative fortress to New Atheism from which to lob flaming rocks or be an apologist for some outdated religious worldview.

I’m here because I bleed, because we all bleed. I’m here because we are all a little like that perennial philosopher Winnie-the-Pooh who we are introduced to in the following way,

Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin. It is, as far as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that there really is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it

Like this bear it can often feel like we’re all bumping our heads as we journey through life. Not sure we’re doing it right and trying to find a slightly less painful way to journey.

So what has this to do with New Atheism?

Well I want to argue that religious beliefs are often used to cover over our anxiety and prevent an encounter with this disturbing feeling, and that, while New Atheism is better than the fundamentalism it critiques, it is ultimately caught up in some of the same problems as that which it attacks, acting as a new means of creating a sense of mastery, solidifying tribal identity and ultimately hiding from us an experience of our unknowing.

To explore this I wish to make three interconnected points.

Point 1: New Atheism is a shadow of the fundamentalism it attacks

Firstly, I want to argue that New Atheism treats fundamentalism as a problem rather than as the solution to a problem.

To understand this we can look at how alcohol abuse functions. The excessive alcohol consumption is not the problem, but an attempt at self-cure, it is then the solution to a problem. If the person doesn’t deal with the problem for which the alcohol is the solution they will always struggle. Even if they do manage to stop drinking another symptom will simply arise whether that be chain smoking, excessive fitness or bouts of aggression.

In a structurally similar way, instead of seeing fundamentalism as a problem it is more helpful to see it as a defense mechanism that is providing a psychological service to the individual. Because of this, if someone gives up their religious fundamentalism and adopts a new system, without addressing why they embraced religious fundamentalism in the first place, the new system will simply function in the same way as the old one.

For example, in Northern Ireland, it is not uncommon to see a former paramilitary join the church. But generally the type of religious commitment they adopt has the same belligerence, intolerance and tribal markers as their previous political fundamentalism. Why? Because their new found religious belief is functioning in the same way as their political fundamentalism. Namely protecting the person from dealing with a complex set of personal and political antagonisms.

In response to this the New Atheist will point out that they are not advocating another system, but rather are offering the critique of a system. They claim that atheism is a religion in the same way that baldness is a hairstyle or health is a disease i.e. it isn’t.

However this answer fails to address the way in which even the rejection of a system can itself operate in structurally the same way as a system. In other words, “Nothing” can be given a positive charge and can act as a tribal identity.

This is captured beautifully in a joke that Derrida would tell of a Rabbi walking into a synagogue and publically saying, “I am dust, I am nothing.” Then a priest came in and did the same. Followed by an Imam. Finally the caretaker of the building entered and also said, “I am dust, I am nothing.” On hearing this the three religious leaders turn to each other and whisper, “who does he think he is, saying that he’s nothing?”

The simple point here is that even a negation can take on a substantive form for the one holding it, and thus can become a new form of protection mechanism. It is this that we can see in New Atheism, where its rejection of a religious system takes on a religious texture and tone.

In contrast, the “New Religion” that I am advocating doesn’t operate at the level of what one believes (offering a new system), but rather asks how our various beliefs function. Inviting us to ask ourselves whether our various beliefs (and even our professed non-beliefs… “I’m not like them”) function.

Point 2: New Atheism strengthens the fundamentalism it critiques by directly attacking it

Secondly, it can be argued that, by directly attacking fundamentalism, New Atheism only strengthens its power. This is because fundamentalism, as a defense mechanism, is strengthened by direct attack. A defense mechanism, like the dark force in The Fifth Element, only becomes stronger when directly attacked.

Imagine that you have just had an argument with your mum. If I see this and berate you for what you said you’re more likely to defend yourself, even if you feel that you might have acted badly. In contrast, if I buy you a drink, have some small talk, and then ask how you felt about the argument, you’re more likely to admit to having overreacted.

The point here is that my direct assault on your actions naturally evokes a defense and ends up doing the opposite of what I want. Instead I must find an indirect means of bringing the issue up.

This, of course, presupposes that you have doubts over the position you’re defending, and this brings me to another problem with New Atheism: it treats fundamentalists as if they naively believe what they’re saying and thus the mere supplying of information will be sufficient.

However one of the weaknesses of fundamentalism is precisely found in its seeming strength, i.e. its aggressive overconfidence when directly confronted hints at the existence of a repressed or disavowed insecurity. The more aggressive someone is at being contradicted the more insecure they generally are. Someone who is genuinely secure in her position will not be angry when challenged, but rather indifferent.

The point then is that the more attacked a fundamentalist feels the more they will hold onto their belief, but the more they are given space in a non-aggressive atmosphere the more likely they are, with the right prompts, to begin to admit to their doubts.

The approach that I advocate uses parables, stories and the Christian tradition itself to create non-aggressive prompts that help people with repressive religious beliefs to glimpse the undying traumas hidden by those beliefs in a way that they can deal with.

This approach thus operates from within religious discourse, drawing out those central elements that break open new possibilities and allow us to glimpse the reasons why a person might be holding onto an unhealthy and morally problematic system.

Point 3: New Atheism isn’t well equipped to help people experience the humility it proclaims

By this I mean that we embrace a more humble comportment to the world, not through a change in worldview, but through rituals and communities that help us face our struggles and narcissism.

Take the example of breaking up with someone. If we complain to a friend about all the times our ex did something wrong and, in the midst of this our friend stops us to correct our interpretation, we might tell them that we already know that our interpretation is wrong. That we are well aware that we are not taking into consideration the other person’s perspective etc. The point is that we need to rant and rave a little so that we can come to accept that. In other words, we need the space to shout in order to get a better perspective on the situation, a perspective that we already are dimly aware of. More than that we also need certain activities to help in gaining a better perspective. Perhaps listening to certain songs, burying shared things or just having a drink with someone who’ll listen to us.

Here we come to embrace the fact that we are not the center of our own universe at a deeply personal level. We can easily understand that we are not the center of the universe in a cosmological sense while still acting in a way that betrays our embedded belief that we are the center of the universe. In contrast, the approach being called here “New Religion” doesn’t seek to bring about a sense of humility by giving people the “correct” way of seeing ones place in the universe, but rather by helping people encounter their own violence and encourage concern for the other through the use of various rituals.

Conclusion

The “what” of our belief is important, however we need spaces were we explore how our beliefs function. Indeed often we can use the debates over what we believe to avoid the more difficult question of asking whether they are a symptom.

Take the example of Batman. He might look brave; going out and taking on the criminal underworld. However this activity actually comes from his fear of dealing with the death of his parents. His seeming bravery covers over a cowardly refusal to deal with issues. One might want to say that the result is still good, however the point is that Batman could make a far bigger impact on Gotham city if he spent his money on after schools programs, health care and job training, than on high tech military hardware.

In an analogous way fighting and dying for ones metaphysical beliefs can be the activity of someone who is unwilling to do the really difficult work of looking at why they hold them in the first place. It becomes easier to fight for them than question them.

So then, by directly attacking fundamentalism New Atheists end up taking on the same form (albeit as an antithesis) of that which they oppose. In addition to this they also strengthen their enemy by directly feeding it. Instead, what we need are places were people can lay down their various weapons and ask themselves what all the fighting covers up. It is at the level of the how that “New Religion” (as it is being called here) operates.

October 26, 2013

No Conviction

Recently I locked myself away and recorded The Orthodox Heretic. To add a little extra spice to the subversive mix we also added a touch of ambient dubstep from the artist Dubh. Below is the first parable from the book.

If you click here you will also find a free audio version of a different parable.

In a world where following Christ is decreed to be a subversive and illegal activity you have been accused of being a believer, arrested, and dragged before a court.

You have been under clandestine surveillance for some time now, and so the prosecution has been able to build up quite a case against you. They begin the trial by offering the judge dozens of photographs that show you attending church meetings, speaking at religious events, and participating in various prayer and worship services. After this, they present a selection of items that have been confiscated from your home: religious books that you own, worship CDs, and other Christian artifacts. Then they step up the pace by displaying many of the poems, pieces of prose, and journal entries that you had lovingly written concerning your faith. Finally, in closing, the prosecution offers your Bible to the judge. This is a well-worn book with scribbles, notes, drawings, and underlings throughout, evidence, if it were needed, that you had read and re-read this sacred text many times.

Throughout the case you have been sitting silently in fear and trembling. You know deep in your heart that with the large body of evidence that has been amassed by the prosecution you face the possibility of a long imprisonment or even execution. At various times throughout the proceedings you have lost all confidence and have been on the verge of standing up and denying Christ. But while this thought has plagued your mind throughout the trial, you resist the temptation and remain focused.

Once the prosecution has finished presenting their case the judge proceeds to ask if you have anything to add, but you remain silent and resolute, terrified that if you open your mouth, even for a moment, you might deny the charges made against you. Like Christ, you remain silent before your accusers. In response you are led outside to wait as the judge ponders your case.

The hours pass slowly as you sit under guard in the foyer waiting to be summoned back. Eventually a young man in uniform appears and leads you into the courtroom so that you may hear the verdict and receive word of your punishment. Once you have been seated in the dock the judge, a harsh and unyielding man, enters the room, stands before you, looks deep into your eyes and begins to speak,

“Of the charges that have been brought forward I find the accused not guilty.”

“Not guilty?” your heart freezes. Then, in a split second, the fear and terror that had moments before threatened to strip your resolve are swallowed up by confusion and rage.

Despite the surroundings, you stand defiantly before the judge and demand that he give an account concerning why you are innocent of the charges in light of the evidence.

“What evidence?” he replies in shock.

“What about the poems and prose that I wrote?” you reply.

“They simply show that you think of yourself as a poet, nothing more.”

“But what about the services I spoke at, the times I wept in church and the long, sleepless nights of prayer?”

“Evidence that you are a good speaker and actor, nothing more.” replied the judge, “It is obvious that you deluded those around you, and perhaps at times you even deluded yourself, but this foolishness is not enough to convict you in a court of law.”

“But this is madness!” you shout. “It would seem that no evidence would convince you!”

“Not so,” replies the judge as if informing you of a great, long-forgotten secret.

“The court is indifferent toward your Bible reading and church attendance; it has no concern for worship with words and a pen. Continue to develop your theology, and use it to paint pictures of love. We have no interest in such armchair artists who spend their time creating images of a better world. We exist only for those who would lay down that brush, and their life, in a Christlike endeavor to create a better world. So, until you live as Christ and his followers did, until you challenge this system and become a thorn in our side, until you die to yourself and offer your body to the flames, until then, my friend, you are no enemy of ours.”

Comments on the book,

“I remember driving around Belfast with Pete, sitting in the front seat listening to him tell these parables—thinking, ‘Everybody needs to hear these.’ Well now you can!”

—Rob Bell

Rollins has already established himself as a major voice and an astute, generative force within the emergence Christianity. The Orthodox Heretic is his most accessible and engaging work to date.”

—Phyllis Tickle

September 30, 2013

The Church With/Out God

September 6, 2013

Rhythm & Disharmony, Rapid City, SD

The God Product, Rapid City, SD

September 4, 2013

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas: Interview

As part of my Playing With Fire tour in Australia this year I am very excited to be participating in The Festival of Dangerous Ideas in the Sydney Opera House. In my first session, entitled New Religion vs. New Atheism, I will be debating the theoretical physicist and cosmologist Lawrence M. Krauss (the event has sold out), while in To Believe is Human; to Doubt, Divine I will be proclaiming the Good News that we can’t be satisfied, that life is tough, and we that don’t know the secret!

In the run up to the event the Festival organizers interviewed me. I thought I would reproduce it here

Q: What makes an idea “dangerous”?

I guess you could describe a dangerous idea as one that has the power to really change things. When people hear the term “dangerous idea” they no doubt think of Fascism or National Socialism or other ideas that do violence against others. But the violence of these ideas belies their underlying impotence. They are like a man who beats his partner. The outburst of the man is a sign of weakness, evidence that he is unable to make real change in his life and who is thus blaming another and acting out against them. Many ideologies function in this way, finding a victim to blame for societal problems and acting out against them. More than this they are attempts at ensuring that nothing changes (protecting the powerful against the powerless). The the most disgusting ideologies are precisely that, means of absolving responsibility and maintaing the status quo at all costs. The real examples of people with dangerous ideas are the ones like Martin Luther King Jr, Mother Teresa, or Mahatma Gandhi. For these people had ideas that fundamentally changed the power structures of their day. Whether it is in the are of politics, science, philosophy or technology the people with the dangerious ideas are the ones that have the power to really change the world for the better.

Q: Which technological or scientific advancement excites you most?

Scientists and technologists have an interesting relationship. The scientists are the ones who are doing the exciting work of deciphering the universe, they generally don’t care that much about what the results of their research will be. Indeed it is often hard to work out what practical use the latest findings in something like the realm of physics will be. It is the ones working in technology who have the job of making the latest findings in CERN impact the world. I guess where I see some exciting developments here are in the area of renewable energy, electric transport and mobile health units that can test your blood, urine and saliva through a device you plug into your smart phone.

Q: Which social or political movement scares you most?

It is easy to point toward the growth of various fundamentalisms as scary, but liberalism itself might be even more frightening. By this I mean that we are perhaps part of a system in which we hide our violence far away, preferring not to see the results of our lifestyle on others. It might be liberalism itself that actually generates the very conditions within which fundamentalism grows by contributing to the suffering of people in various parts of the world. The scary thing for people like me is to try and face up to my own involvement in violence and attempt to effectuate change where I am.

Q: What’s the one thing you wish society better understood?

Ourselves. I know that can sound somewhat trite, but I think that so much of the violence we see in the world comes from our inability to look at and deal with the anxieties, fears and traumas within. Instead we project out to others, seeing them as the problem. We fall victim to ideas that tell us some new eden is possible if only some x (the Jew, the Muslim etc.) wasn’t there. We cannot face our own inner antagonisms and so we are more prone to create antagonisms with others. It is not an easy task to know oneself better, indeed part of knowing oneself better involves accepting that we are a mystery to ourselves and making peace with that.

Q: Will the defining catastrophe of the next decade be natural or man-made?

People often talk about the coming catastrophe, but to be honest I don’t think its coming, I think it is already here. Our system functions precisely in its ability to manage, compartmentalize, shift, and hide catastrophes. Whole species are being wiped out, countries are poverty stricken, unemployment is rife, prejudice is enshrined in laws and starvation is a reality for millions. Maybe something worse is coming over the horizon, but I think in many ways we need to open our eyes and see that we are living in a type of apocalyptic end times.

Q: What question have you been dying to ask someone (and who)?

That’s an interesting question. I’m reminded of Sartre who was approached by a student who asked him a question. Sartre looked at him and said, “why are you asking? You already know me and what I would likely say, hence by approaching me you already know the type of advice you want to receive and can thus skip talking to me.” The point here is that Sartre was pointing out that questions and who we direct them too can betray our own conservatism (our desire to hear back what we already know dimly). For instance a Republican in the US will likely ask a question to someone in their party who holds the views they already endorse, or ask a question of someone in the other party to confirm their dislike of the person.

The people I am most challenged by are the ones who take my questions and show how they assume lots of things that themselves should be questioned, who refuse to answer me and force me to do the work. That is one of the roles of philosophers, to help us see what our questions presuppose, to question our questions, interrogate them and perhaps get us to ask better ones.

Q: What question have you been dying for someone to ask you?

This one

Q: If you could outsource one part of your life, what would it be?

I guess the personal stuff. I’ve got worse at that kind of thing as I have got older and we all know that relationships can be painful. But then again, if I outsourced that I’d probably have nothing to write about. Many writers, artists and musicians are successful in their fields precisely because they are so unsuccessful in their personal lives.

Q: What’s your favorite book and why?

I guess my favorite book is always the one I am on the threshold of reading, the one that holds out the promise that it will give me insights, explain the universe, and help me understand my anxiety. I think that is what inspires me to keep reading, looking for that impossible book that will give the answers. Sadly no books can do that, except my own of course!

September 3, 2013

While We Live We Are Eternal: The Interrelation of Past, Present and Future

The popular view time conceives of it as a series of present moments that flow into the past and march forth into the future. From this perspective all we really have is the “now”: an elusive moment (for as soon as we try to mark it, it is already over) in which we currently reside.

The popular view time conceives of it as a series of present moments that flow into the past and march forth into the future. From this perspective all we really have is the “now”: an elusive moment (for as soon as we try to mark it, it is already over) in which we currently reside.

This broadly pagan conception of time, in which the past has gone and the future is yet to come, can be contrasted with the classical notion of a timeless being that simultaneously inhabits the past, present and future.

It was Kierkegaard, in wrestling what it might mean for the eternal to break into the temporal, who was able to conceptualize a fundamentally different experience of time, one that worked off the classical notion of a timeless realm in which past, present and future co-exist.

He felt that the Incarnation revealed a different experience of time, for it described the timeless dimension entering into and disrupting the temporal.

This allowed him to think of the individual as no longer experiencing their existence as a slice of ungraspable “nows” always giving way to an as yet non-existent future and dissolving into a no longer existing past.

Instead the subject lives simultaneously in the past, present and future. Each one informing, inhabiting and re-visioning the others.

What this means is that the past is inscribed into the present as a living memory, and into the future as a range of possibilities. In turn the present is always able to reconstruct and revise the past while rethinking the future through new expectations. Lastly the future, as anticipation, itself reaches back into our present, influencing our current life decisions, and even further back into our past, causing us to rethink the meaning of what has already transpired.

To take one example, a lonely and abusive past can be re-envisioned by an individual in light of a positive encounter in the present, an encounter that itself changes the future of that person. Perhaps the individual falls in love and suddenly experiences the previously unbearable weight of the past as a time of preparation for this new love. This also frees them from a future in which they are condemned to return to the pain of the past. The point here is simply that the past and future are fluid, influenced as they are by an apocalyptic (meaning utterly unforeseeable) intervention in the present.

This is also the conception of time that we find in the psychoanalytic clinic. Here the one undergoing analysis (the analysand) discovers how past and future are inscribed into their present in various complex ways, and the role of the analyst involves making incisions into their discourse that might help them transform the way they comport themselves to these. In short, robbing the past and future of their oppressive power through an intervention in the present.

This notion of time can be described as the eternal existing in the passing. For the classical theological understanding of the eternal, as a simultaneous dwelling in past, present and future, is inscribed into our very lived experience.

Instead of the eternal being simply the ongoing now (the pagan notion), this understanding sees the eternal as the dwelling in all three registers. This is nothing less than the combining of past, present and future into a mass of infinite density that changes depending upon the way we observe them rather than some entropic, reified dissipation of now into a never-ending future.

August 24, 2013

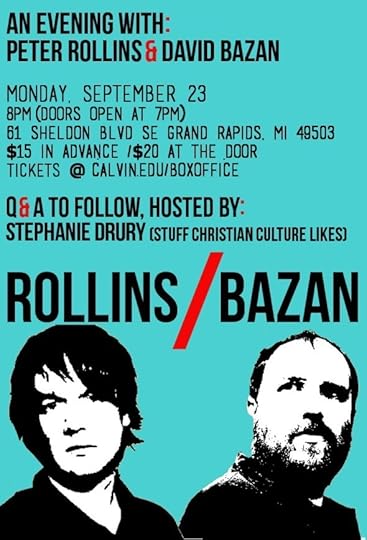

Rollins and Bazan, Grand Rapids, MI

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers