Peter Rollins's Blog, page 29

March 25, 2014

God is (the) Real

On twitter I occasionally get asked what I think about the existence of God. It’s usually asked by someone who has a solid grasp of what the term “God” refers to, and they assume that it has the same meaning for everyone else. Hence there is confusion when I reply that I can’t answer in 140 characters. The response is usually that the question is an easy one to answer: yes, no, or not sure.

However the word “God” is anything but simple or stable, and so an answer to the question of “do you believe in God” must be preceded by the question, “what do we mean by the term ‘God’.”

In order to approach an answer to this question I want to make use of a tripartite frame that Lacan developed to understand our subjective world. Lacan taught that our inner universe can be understood through reference to three interconnected registers: the Imaginary, the Symbolic and the Real.

These are somewhat slippery concepts to get a handle on, but for our purposes we can make use of them without fully defining them. To do this I’ll refer to what it means to treat someone through the filter of the first two registers.

We treat someone at the imaginary level when we see him or her as fundamentally like us. In other words, they are someone who we can admire, love, hate, be jealous of etc. This is relatively easy to understand as we’re broadly aware of the way we exist in competition, or solidarity, with those around us.

When we treat someone in a more symbolic way they operate as a type of stand in for a more basic type of relation. To understand this we can think of how a person might treat their analyst. For example, an individual might relay a dream during their session and then say, “I know what you’re thinking, you’re thinking that I resent my mother.” In actual fact the analyst (who is not an expert on your unconscious) is unlikely to have an immediate interpretation of what they’ve said. The claim, “I know what you’re thinking,” is more likely to reflect what the person themselves is thinking, but are unaware of. At this point the analyst might respond by showing surprise or interest in the fact that the analysand assumed what they did. In this exchange the analysand treats the analyst in a more symbolic way. The analyst effectively becomes a type of screen upon which the person’s unconscious is projected (and thus can reflect that projection back to the speaker).

In terms of religion, when the word “God” is employed I would argue that it is used primarily in one of these registers. In popular discourse “God” is basically understood in an Imaginary manner. God is a being like us, a being who speaks, thinks, desires etc. God is a being who we can love, hate, argue with and make up to. The difference between the theist and the atheist here revolves around the idea of whether this God exists or not.

In traditional theological circles God operates more on the Symbolic level. Here God is not named as such, it is claimed that what we say about God reflects ourselves and that we must speak of God as “beyond being,” “ground of being,” or in some other way that avoids the idea of us “speaking of ourselves in a loud voice” (Karl Barth). It is claimed that there is an ineffable reality to God that cannot be penetrated; yet this impenetrable God exposes us to ourselves.

In addition to the Imaginary and the Symbolic registers, Lacan also spoke of the Real. For Lacan, the Real is that which breaks into our Imaginary and Symbolic constellations. The Real is a rupture. The Real cannot be imagined or symbolized, it does not occupy a place, and yet it takes place. The Real is a crack within our existing political, religious and cultural configurations, a resistance that prevents systems from claiming absolute knowledge. It is a destabilizing event that threatens to disrupt the balance maintained by our ideological commitments.

It would seem to me that primitive religion understands God in a predominately Imaginary register (from the Greek gods of antiquity right through to the gods of Western fundamentalism), while theology tends to treat God at the level of the Symbolic (onto-theology and apophatic thought). In contrast I employ the term “God” primarily as a name for the Real. Indeed the collectives that I’m part of setting up are primarily committed to this idea of evoking the Real.

March 23, 2014

I had a Horrible Dream in which I Watched You Die

The philosopher Jean Paul Sartre’s view of freedom and responsibility can initially be difficult to grasp. His claim that we are radically free to choose different options at every given moment can sound like he’s saying there’s a part of us that can weigh up different situations and then make a decision concerning what to do in a space unaffected by some causal chain (as well as sounding just plain exhausting).

But Sartre is not claiming that there is some part of us (some ghost in the machine) that is free to choose at any given moment, but rather that we are free. The claim “existence precedes essence” is the claim that consciousness is itself the direct expression of a radical freedom. This means that everything we do is ours to bear and that the denial of responsibility is an act of bad faith.

A good way of thinking about Sartre’s freedom is via reference to Freud’s work with dreams. For Freud there is a sense in which we are responsible for our dreams. They are ours, yet we can’t really control them. We don’t choose our dreams and we rarely get the chance to influence them in a self-conscious way. They feel foreign to us while actually being a deep part of us. In Zizek’s words, they’re a type of alien from inner space (what Lacan called “extimacy”).

This is why, from a Freudian perspective, even those things we dream of which are disturbing to us are a reflection of some ciphered desire or wish. If I have a dream where I see a good friend drowning, I cannot escape the fact that I dreamed it. In the dream I might feel a horrible sense of panic as I stand by the water and watch him disappear beneath it, but the sense of panic can actually be the defense I employ to protect myself from confronting the desire I have.

The feeling of horror provides a way for me to censor my desire from myself because of the self-disgust I would otherwise feel. The jealousy or hatred that I might harbor against him is effectively masked by my seeming emotional protest.

It is this same logic that we witness in statements such as “I’m not a racist, but…” or “I mean no offense, however…” Here we witness how a person is able to express racism or personal insult while protecting their self-image. When a person writes, “I hate to say this, but…” one thing that is generally clear is that they very much don’t hate saying it, indeed they elicit a certain amount of pleasure from the statement.

March 21, 2014

Osteen, Driscoll and the Masking of our Ideology

I once attended a conference where a religious presenter attempted to defend authentic marriage. In his argument he referred to a problem he felt was created by the kind of celebrity marriages witnessed on TV. He argued that these take away from the depth and authenticity of true marriage by giving people unreasonable expectations concerning both the day and what will happen after it. As part of his defense he even evoked the name of Jean Baudrillard (author of Simulacra and Simulation).

But the approach taken by the presenter was actually a perfect case of what Baudrillard was arguing against. The logic of Baudrillard is not that celebrity marriages mask or eclipse some authentic marriage ritual, but rather that they actually help support the idea that there is such a thing as an authentic marriage ritual.

The obviously fanciful spectacle, in other words, enables people (like this presenter) to argue that there is an authentic alternative located in reality.

“Real” or “authentic” marriage ceremonies are themselves a form of contrivance that can encourage unrealistic expectations and demands. The ancient rituals such as the exchange of rings, declaration of vows, or giving of the bride are all performances taken from religious systems that have simply been around for longer than the type of thing we might witness on the fantasy of reality TV.

Places like Disney World are problematic in the same way because the very fantasy they create actually sustains the idea that the way we structure our lives outside that space is somehow the way things really are, rather than itself an expression of fantasy. The very fact that we can easily discern that Disney World is ideological means that we are more likely to forget that we ourselves are immersed in ideology in our daily life.

One of the main problems with the extravagant forms of religious ideology we see played out in figures like Joel Osteen and Mark Driscoll might not lie in their own obviously ideological character, but in the way that they solidify the idea that there is a non ideological community beyond them (one somehow not immersed in Western Values etc.).

Witnessing their overt ideology thus plays into the hands of those who would like to ignore their own ideological saturation.

The Walt Disney World of Osteen’s church and the Hell House adventure of Driscoll’s communities are then dangerous precisely because they can prevent us from seeing the political and cultural constellation of our own positions.

March 8, 2014

On Keeping Ones Distance from God’s Desire (a Reflection on the First Four Major Covenants)

There are, broadly speaking, five major covenants in the biblical canon: the Noahic, Abrahamic, Mosaic and Davidic, and the “New Covenant.” In this post I want to reflect a little on the role of the first four, with a later reflection on the role of the fifth. These are basic reflections that will, one day, be elaborated in a book and/or series of talks (they are reflections based on my reading/interpretation of Lacan and Zizek).

At a popular level it is thought that the point of contracts or covenants in the Biblical text is to connect people with their God. The five major covenants exist as form of binding one to the sacred. However, at a fundamental level, covenants exist as a means of helping us maintain a distance from the one we are interacting with. In this way the first four biblical covenants can be read more accurately as a means of people creating a distance from the sacred (with the last, I will argue elsewhere, signaling a radical cut).

To understand the nature of this distance it’s worth reflecting on how all covenants are designed to protect us from a very specific thing.

Firstly, we can note that covenants exist to navigate an already existing, or soon to exist, social relation. Take the example of a contract made during a divorce. The contract comes into being precisely because two people are already connected in some way. The contract thus exists to manage that relation. More precisely, it exists to separate each party from that deepest part of the other: their desire.

The contract used in a divorce is needed so that each party knows what their rights and responsibilities are regardless of personal feeling. The contract might outline when each party can see their children, how much alimony is to be paid or who has the final decisions in various matters. Perhaps one of the parents decides that he doesn’t want the other to see the children, or the other stops paying her fair share of costs for the child. Without such a contract these situations can easily degenerate into all out conflict. A contract can thus be seen to outline what everyone needs to adhere to: thus protecting both parties from becoming victims of the others shifting wants and desires.

The same goes for students living together (for it doesn’t take long for rota’s to become nessesary in order to ensure that everyone pulls their weight), or marriage (where two people make vows to commit to each other regardless of the ebbs and flows of their desire). Contracts or covenants, at their best, thus offer a mutually agreed set of terms concerning the roles and responsibilities of each party, so that peoples shifting and elusive desires don’t destabilize everything.

In this way covenants, contracts, rotas and vows manage social relations in such a way that parties are protected from the whims of the others desire. They acknowledge a connection (for we would not need them if there were no connection), while protecting us from that deepest part of the other.

In relation to the Hebrew Scriptures we can see how covenants operate with this fundamental logic. There are numerous references in the text to the elusive and terrifying nature of God’s desire. Times of peace, victory in war, and prosperity are often put down to God’s favor, but floods, plagues, doubts, and famines are generally taken to be evidence of God’s anger and jealousy.

In such a world covenants offered protection from these divine whims. There were clear instructions, alongside roles and responsibilities. If the covenant was obeyed then everything would be good, and if it wasn’t then there would be hell to pay. This then created a distance from the elusive desire of God, meaning that they could get on with other things.

This structurally reflects some of the anxiety that young children feel with their (real or symbolic) mother. While an infant will seek intimacy with their mother, there is also a psychological stifling that takes place if the relation is too close for too long. For the infant to develop her own sense of self apart from the mother a cut must be introduced. This cut is called the Name-of-the-Father” in Lacanian psychoanalysis, and it refers to that which gets in the way of the mother-child relation (this doesn’t need to be the actual father anymore than the initial connection needs to be with the actual mother).

If things go to plan the child experiences a type of psychological alienation from the mother, realizing that she has other interests and desires outside of their relationship. More than this, the child begins to create her own realm apart from the mother. If the mother is too overbearing then the child will tend to feel suffocated and anxious, wondering what the mother wants from her.

In very concrete terms we witness, within Judaism, the practical outworking of this distance. While belief in God still has a reasonably significant place within Judaism (though much less than actual existing Christianity), there is a certain palpable distance from God’s desire. What matters more are the rituals and practices, which are often carried out as rigorously among secular Jews as religious ones. Indeed the Midrash is well know to contain stories that explicitly draw this distance out, something that explored by Emmanuel Levinas.

When approaching these covenants in this way we can begin to understand why Radical Theology doesn’t see religion proper as a means of bringing us close to the divine, but rather as a means of breaking us free from the divine. In a specifically Lacanian theology, this breaking free is not related to some kind of intellectual belief, but to divine desire. A Lacanian reading of religion involves drawing out those parts of the tradition that seek to distance us from the Big Other in whatever form that Big Other takes.

The Radical Church is thus charged with the task of helping mimic that space so that those involved can take full responsibility for their actions.

These are only provisional reflections on the first four covenants. I hope to reflect on the role of the fifth soon and bring these together in a much deeper way in the future. This should help to explain the theory behind my project: building Radical expressions of Church.

March 7, 2014

Atheism for Lent, Online Course

For a number of years I have been developing and running a course entitled “Atheism for Lent.” This is a Lenten practice in which a group tarries with some of the greatest, most perceptive criticisms and critiques of God, religion, and faith.

In order to bring this to the next level I am joining forces with Tripp Fuller to provide an in-depth, intensive, and hopefully entertaining version of the practice.

This purifying practice offers one of the most creative and provocative ways to approach the Good Friday, where Christ himself cry’s out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.”

Over six weeks we’ll explore six readings from six seminal thinkers. So far we’re committed to covering Feuerbach, Freud and Nietzsche.

Each week includes,

- A live 90 minute video session composed of a lecture by Peter or Tripp and Q&A

- PDFs of the Texts

- A private group discussion board

- Recorded Audio of the previous sessions for review or catch up

February 17, 2014

Questioning Theology: Reflections on De-Centering Practices

A theology that’s genuinely open to questioning eventually hits a point when it must question itself: a sustained questing theology thus inevitably leads to the point of questioning theology.

This means that the very base from which theological questions are asked itself becomes a question. Apophatic theology (the name given to negative theology) here gives way to a type of auto-deconstructive thinking that uproots and upsets confessional theology without leaving it behind.

This is, at any rate, the direction that my own work has taken, from How (Not) to Speak of God through to Idolatry of God and into my forthcoming The Divine Magician. This approach questions confessional theology from within, opening it up to acknowledging the operative forces of contingency, history and fluidity.

More than this, the auto-deconstructive approach to theology is one that opens up a fundamentally different way of understanding faith, an understanding that is rooted in a form of life rather than the affirmation of some particular belief.

Dialectically speaking kataphatic thinking (affirmative theology) gives way to apophatic thinking (negative theology) that in turn opens up to forms of radical theology (a theology that negates the negation of apophatic thought). Although, strictly speaking, one could argue that the experience of the apophatic comes first.

While this might sound rather abstract and theoretical, the point I want to make is fundamentally a pastoral one. For those of us who want to introduce fluidity to confessional theologies that are too rigid, and open up paths toward a radical faith beyond belief (playing on the ambiguity of that phrase) all we need to do is encourage people to ask questions from within the tradition they already find themselves.

In the words of John Caputo, we must help them discover the power of the word ‘perhaps,’ introducing it into the lexicon of their dogmatic assertions. While this can sound simple, the problem is that this requires great courage. As I have argued elsewhere, it’s often easier to die for our beliefs (or kill for them) rather than to question them.

What we must do then is walk this path ourselves, build mutual respect and trust with other in our traditions, and carefully curate spaces that encourage this questioning; providing practices that allow the power of perhaps to deepen and widen.

In my own work I have developed what I call De-centering Practices. These are practices that help people undergo a form of lived deconstruction. One that, I believe, opens the way up to a richer, though not necessarily happier, experience of life (what this might mean is a subject that we can’t go into here).

If you’re interested in finding out more about de-centering practices I’d encourage you to watch and discuss the following videos with friends and colleagues. They provide a little information concerning what de-centering practices can look like. There are numerous communities engaging in these practices already and my hope is that you might consider either copying one of those mentioned in the videos, or create one of your own.

February 13, 2014

Faith as Constant Revolution: Some Thoughts on Heretics, Tricksters and Cynics

Fundamental reformations that transform the constellation we use to navigate and understand religious life have occurred at various times throughout history. These events don’t simply call religion to live up to its ideals, but rather transform the very way we understand those ideals. They are thus fundamental ruptures in the very coordinates of religious understanding.

Words like “religion,” “church,” “God,” “theist,” “atheist,” and “theology” continue to be used, but what these words harbor is so dramatically transformed that the new meanings blow up the old (much to the surprise and consternation of the establishment).

When a religious system starts to be questioned at this (qualitative rather than quantitative) level, it’s possible to identify some revolutionary group both stirring up trouble and getting into trouble. Depending upon the context, the trouble they get into might range from social exclusion and job loss to torture and execution.

But time and again the system (1) identities heretics (dissidents within the system, in contrast to agitators from outside the system), (2) attempts to inoculate itself against them, and (3) seeks to eliminate them. After the dust has settled either the old master has retained power, or a new master is crowned (who might be more benevolent than the last).

The heretic can thus be said to operate in the space between two masters. Asking questions, critiquing the status quo and refusing easy answers. They are the tricksters and the cynics who occupy existing structures in order to subvert the present order and reveal inherent antagonisms in the system. This tradition of the trickster has a long history with figures including Prometheus (Greek mythology), Diogenes (Greek philosophy), the Coyote and Raven (First Nation mythologies) and Mercurious (Roman mythology), right through numerous religious prophets and into modern figures like Charlie Chaplin (to name but a few).

The question often asked in these moments of upheaval concerns what the new system will look like, what the new orthodoxy will be. When the tricksters have had their day, what will be left, and what foundations will we have upon which to build/rebuild.

However, what if this space of the in-between is itself the alternative? What if this protest is the very space that we need to affirm? Or rather, what if heresy is not something that arises from some structure called “faith,” but rather that “faith” can be used as the name of the very act of heresy?

If faith is thought of as a protest against existing masters, then the person of faith is one committed to the ongoing struggle with and against structures of power. Which means also undermining those structures in themselves.

The notion that revolutions (political, religious and/or cultural) are problematic because of the way that they simply “revolve” (i.e. overthrow old masters to institute new ones) thus misses the fundamentally productive nature of grassroots revolutionary justice movements. For while these movement do revolve, they are at their best when they act like a needle on a record, with the next revolution of the needle happening on a different level than the last.

A productive revolution places us in a better circle than the previous one, handing on the baton to the next band of heretics. In other words, it’s true that new masters will arise, but moral victories can be gained (marriage equality etc.) and these new masters will themselves be overturned in the name of what Derrida called an undeconstructable justice.

In this way, the figure of the one in exile, the one who questions, subverts, and overturns the establishment, is not that of a mere transitional bridge leading to a more honest and authentic expression of faith, but rather they act as a direct expression of it.

February 3, 2014

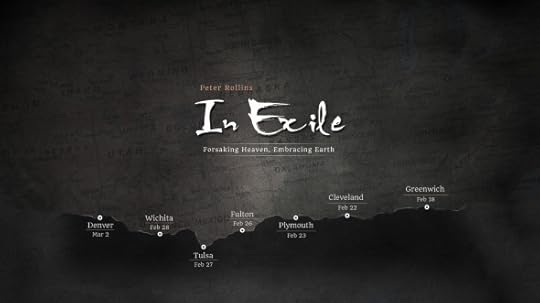

In Exile, Road Trip

Ten years ago I wrote my first book, How (Not) to Speak of God. At the beginning of the first chapter I relayed the parable of a young traveller who was busy preparing his horse for a long and arduous journey,

As he packed his few possessions an old friend approaches and asks, ‘Where are you going?’ Without looking up, the traveller quietly replies, ‘Away from here.’ After a short pause his friend repeats the question, and again the traveller responds by saying, ‘I am going away from here.’ Finally the friend exclaims, ‘I already know that you are leaving us, but what is your destination?’ In response the traveller stops what he is doing and looks directly into the eyes of his companion. ‘I have already told you my destination, dear friend. It is away-from-here.’

This parable, more than ever, touches on a subject that continues to be central to my project (as well as my life). As I get ready to move from what has been my home for the last four years, this theme is haunting me more than ever. So as I drive across the country, working out where I will settle for the next part of my life, I’ll be stoping in a few spots and exploring the themes of journey, exile, and embracing the unknown.

Apart from storytelling and philosophical reflections I’m hoping to make new friends, connect with old ones, and have a few drinks along the way.

I hope to see some of you on the way.

Feb 18th | Greenwich, CT

Christ Church Bookstore | 254 E Putnam Avenue

Doors TBC | Event TBC

Click here to register attendance

Feb 22 | Cleveland, OH

St. John Episcopal Church | 2600 Church Street

Doors 6:30 | Event 7

Feb 23 | Plymouth, IN

Trinity UMC | 425 South Michigan Street

Doors 5:30 | Event 6

Feb 26 |Fulton, MO

Coulter Science Center Lecture Hall | 501 Westminster Avenue

Doors 6:30 | Event 7

Feb 27 | Tulsa, OK

Foolish Things Cafe | 1001 S. Main Street

Doors 6:30 | Event 7

Numbers are limited so please register here if you plan to go

Feb 28 | Wichita, KS

TBC

Mar 2 | Denver, CO

TBC

January 21, 2014

Life Before Death, Glendale, CA

Join me at 7pm in Central Avenue Church (725 North Central Avenue, Glendale, CA) as I explore a way of reading faith as a mode of life rather than as a system of belief.

January 14, 2014

SCM, Derbyshire, UK

This will be an event run by the PCN and SCM. Other speakers include George Elerick and Katherine Moody. It will be held at the Hayes Conference Centre in Swanwick, Derbyshire. More information will be posted up here a few months before the event.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers