Peter Rollins's Blog, page 18

April 28, 2015

Dreaming into the World: Beyond Neurosis, Perversion and Psychosis

One of the critiques often leveled against psychoanalysis is that it is effectively a normalizing discipline. That it aims to integrate the individual back into the social fabric that she feels alienated from.

Politically speaking this is viewed as problematic, for the very experience of psychic alienation testifies to a problematic environment. The truly radical move is not then to reintegrate a community into that system from which their symptom erupts, but rather to help weaponize them so that they might better overcome it. The positions of neurosis, perversion and psychosis are thus romanticized and read as potent outbursts against oppressive systems.

In short, our world is in crisis and the supposedly psychic anomaly of a subjective “disorder” is in fact the Archimedean point to be used for toppling the oppressive system that gave rise to it.

From this perspective the normalizing of the individual or community implies a form of reintegration into a politically, socially or religiously oppressive environment. Instead of birthing a properly dissident political subject, one produces docile and obedient citizens. This critique gains even more persuasive power when one considers how impossible it would be to sustain a therapeutic clinic that seeks to increase dissatisfaction and alienation. The posture of analysis would thus seem to be in opposition to a radically political one.

In light of this there is a tendency for some academics to celebrate the political vitality of neurosis, perversion or psychosis.

Leaning on the insights of Todd McGowan in his excellent Enjoying What we Don’t Have I want to push back on this celebration of such conditions in individual or communal form.

It is true that neurosis, perversion and psychosis are cries against the system that gives rise to them, but the problem in each case lies in the particular way that they remain impotent to change what they cry out against.

In the case of neurosis, the individual or community retreat into fantasy as a means of escaping the exigencies of life. The fantasy provides a way of imagining sexual, political and religious freedom, yet this fantasy doesn’t touch upon the social reality it rejects. It tends to be a retreat from the world as it is, into a purely private world of fantasmic pleasure.

In perversion the individual or community does fight against an oppressive, repressed, and hypocritical system. They don’t retreat into some fantasy life, but attempt to live out their fantasy. Yet the problem here is that the perverse act requires what it fights against, gaining pleasure from provoking the system it rejects. Because of this it becomes a type of transgression that demands what it rejects in order to sustain its libidinal economy.

Finally, in psychosis, one can definitely see an attempt to construct a different type of world that would overcome the one that presently exists. Yet it rarely gains a foothold. In paranoia the individual or community forms a world at radical odds with social reality. It is a world full of dark conspiracies, maniacal villains and insidious plots all aimed at undermining them. Because of the extreme nature of these fantasies it is only in rare moments that they gain any traction at all. The paranoid vision is just too bizarre to make a change and remains on the fringe.

In contrast, psychoanalysis outlines a different approach. It is true that ego psychology can be seen to offer a way of reintegrating people into their social environment, adapting them to their world. However the properly Freudian tradition rejects this. In this tradition the “normal” individual (one who does everything that a given society judges decent, right and upstanding) is considered to be exhibiting a particular type of abnormal reaction.

For Freud, the healthy individual was not someone with only a minimal need for fantasy, i.e. someone so content in their world that they don’t require much of a fantasmic supplement. Rather the healthy individual is able to mobilize their fantasies of a better world so that they directly touch upon the social fabric, contributing to its ongoing transformation. Instead of retreating from the world, the healthy individual or community is able to let their dreams impact the world that sustains them and work for real change. Finding satisfaction in this act.

To contrast this with the neurotic act we can say that our fantasy of a better world is not what we use in order to cope with the painful one we inhabit, but rather is the fuel that feeds our desire to make that world less painful.

This is the difference between a hope that we use to avoid changing the world (e.g. the hope that the next world will be better than this one), and a hope that demands our involvement in changing the world (e.g. the hope that there will be justice for minorities brutalized by the State). In other words, a hope that requires my involvement to become a reality. A theme I take up in The Divine Magician.

April 23, 2015

Executing the Undead God, Glendale, CA

The dead have a disturbing habit of returning to us in spectral form, disturbing the everyday flow of our lives, and disrupting our best-laid plans. Indeed, within the secular world, the God proclaimed dead by Nietzsche continues to haunt us in strange ways. A fact that Nietzsche described as the enduring shadow of God.

In short, while we might be done with the fundamentalist God, this God may not be done with us. In this seminar, Peter will explore these ideas and outline an insurrectionary vision of Christianity that aims squarely at exorcising this spectral figure.

Contrary to what we witness in the actual existing church, Peter will argue that the atheism of today’s religious despisers isn’t atheistic enough, and that the scandalous message of the Gospel is a freedom from the spell of fundamentalism in all its sacred and secular manifestations.

There will be a talk, followed by an interview and Q&A session. Then we’ll retire to a local pub for some informal conversation.

Cost $15

To get a ticket click here

Commons Church, Calgary, AB

From the website: It is with much anticipation that Round Table Initiatives invites Peter Rollins to Calgary to give a lecture this spring! He is known internationally as an engaging and thought-provoking theologian, philosopher, writer, and storyteller. Please join us in welcoming Rollins as we spend an evening exploring and hearing his refreshing perspectives on faith and culture!

Peter gained his higher education from Queens University, Belfast and has earned degrees (with distinction) in Scholastic Philosophy (BA Hons), Political Theory (MA) and Post-Structural thought (PhD). He is the author of numerous books, including Insurrection, The Idolatry of God, and The Divine Magician. He was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland and currently lives in Los Angeles.

Tickets are available through the church for $12 ($15 at the door)

7:30-9:30

Round Table Initiatives, Nordegg, AB

From the website: For this May weekend – Friday, May 22 through Sunday, May 24 – we are pleased to host a Round Table Initiatives gathering at the Goldeye Center with a well-known theologian, philosopher, writer, and speaker named Peter Rollins. Pete is a coyote. He is crafty, quick, wiley, and speaks in many forms. He is a deep well of knowledge and wisdom, and has a love for nonstandard expressions of faith. RTI has a lot to learn from our Irish counterpart and the weekend will be a time dedicated to depth, conversation, gathering, and good companions.

April 7, 2015

2D with Rob Bell

This event is for those who are growing and learning and changing and evolving and you’re discovering that not everyone around you is seeing what you’re seeing. Friends, family, spouses, coworkers, employers-what do you do when you’re more alive than ever, and yet all this new life is also bringing with it all kinds of disruption and grief and criticism and even loneliness? For some of you who are leaders, your growth has direct implications for your employment. For others, the new life you’re experiencing is deeply unsettling for some of your most significant relationships.

It’s designed to help you walk this path with peace and integrity and even joy. I’ll be giving some new talks on courage and fear and the science of the soul.

At the heart of the these two days is the conviction that you can keep going, that you can do your inner work, becoming more courageous and kind and open and compassionate in the process. You are not alone, and if we get a group of us-400 or so-in the same room and talk about these things, who knows what will happen?

April 1, 2015

Soapbox: A Two-Day Course in Public Speaking With Peter Rollins and Special Guests

With the huge popularity surrounding TED talks, stand-up comedians, thoughtful podcasts and university level lectures, the hunger for engaging, entertaining and intriguing pubic speaking is insatiable.

More than ever there are opportunities for writers, teachers, students and leaders of various stripes to make a living from communicating ideas in captivating and compelling ways.

Yet there’s also a poverty of places where people can hone their speaking skills, develop their voice and receive direction. In addition to this, there’s a certain mystique surrounding public speaking, one that is manifest in statements like “they’re just a natural.” While a few individuals might possess a raw talent for public speaking, becoming great involves a lot of hard work and dedication. The most naturally bewitching and enthralling of orators have spent long hours developing their skills.

With this in mind, I’m keen to work with 30 people who would like to develop their public speaking, learn how to cultivate a platform, book events, and carve out a living from the technology of speech.

You might be a professional communicator looking for ways to expand your platform and improve your style, or you might just be starting out. You may feel comfortable standing in front of an audience, or break into a sweat just thinking about it. Either way, this could well be for you. The only criterion is that you’re operating broadly within the same theoretical field as myself. That we share a similar project.

There’ll be a little homework before the event (mainly watching comedians on netflix and reading parables), and there’ll be lots of hard work during it. But we’ll also have time to unwind, drink and hang out.

More information to follow

March 27, 2015

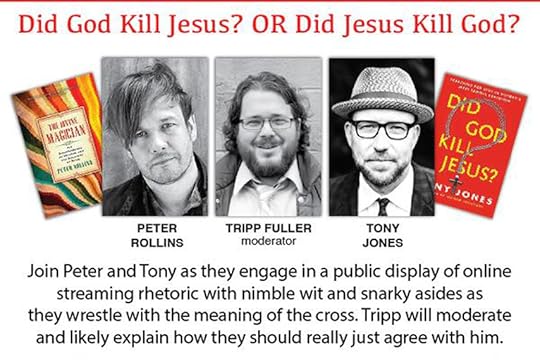

Did God Kill Jesus, or Did Jesus Kill God

On Black Saturday Tony Jones and myself will go head to head in a discussion concerning the significance of the Crucifixion. This will be a theological discussion touching on whether the Crucifixion can be understood within the general framework of theodicy and orthodoxy, or whether it signals the destruction of all such projects, proclaiming the end of religion all overarching frames of meaning. This is a FREE event (though we’d love you to support it by buying the books).

March 26, 2015

Paul and the Crucifixion: Neither Modern, Nor Postmodern

As some of you know, I’m currently teaching a course with Tripp Fuller that explores the turn to Paul found among atheist philosophers. In contrast to the “New Perspective on Paul” found in contemporary theology, people like Badiou, Zizek and Taubes are celebrating a militant, political Paul who provides a model for combating postmodernism.

One of the questions that has come up during the course concerns why on earth these political atheist thinkers would find an ally in Paul when they share nothing of his dogma or commitment to the largely conservative, pietistic community that claims his legacy. More than this, the Resurrection of Christ is Paul’s overriding belief, it is the sun around which everything else orbits.

How then can thinkers who view this part of the Jesus story as a fable, possibly champion the controversial apostle?

In order to approach an answer we have to briefly reflect on how Paul held the belief in Christ’s resurrection. Bearing in mind the centrality of the belief, it is hard not to be struck by the fact that he doesn’t actually argue for it in the traditional way. Indeed he specifically claimed that the event was foolishness in terms of reason, and a stumbling block for those who sought a sign. In this way Paul neither resembles the modern apologist who employs philosophy to back up his claims, nor the postmodernist who sees her claims as relative.

Paul can’t be placed into either of these camps, and instead opens up a different mode of discourse: Proclamation. For Badiou this opens up the figure of the apostle over and against the figure of the philosopher and the prophet.

To understand the atheist philosophers’ enlisting of Paul we have to understand the nature of this third discourse in relation to the statement “Christ is Risen.” The main thing that strikes us when reading Paul’s claim is the way that it isn’t a theory to defend, it is rather an event that is proclaimed and verified in the formation of what Paul Tillich would call, the New Being.

In Badiou’s excellent book on Paul he uses the example of how the belief in the gas chambers used by the Nazis function for us today.

The claim that millions of Jews where executed in these gas chambers is an historical one that is open to verification and falsification. However the way that this claim functions for us cannot be reduced to this level. When someone attempts to draw us into a debate about whether or not these murders really happened, we not only refuse to enter in, we expose how the very reduction of the event to a type of detached historical debate is already a betrayal of the event it signals.

For most of the world the historical belief in the mass murder of Jews in Nazi death camps articulates an event that demands an unconditional stance. The historical record is encountered as something that makes an absolute claim on us. It reflects a horror that we must attempt to ensure never happens again. The contingent historical reality is thus a site of demand. It houses an event that cannot be reduced to the location it was birthed in. An event that is eclipsed the moment we treat the gas Chambers in a cold, detached way.

For Paul the resurrection is a historical reality, but he holds it like one might hold the belief in the gas chambers, i.e. the event housed in the historical claim is not something one debates, holds lightly or defends. For Paul it is proclaimed in the life of the one caught up in the event. For Paul, the idea of playing into the Greek discourse of reason is not simply misplaced, but a fundamental betrayal of the event. In a brilliant reflection from St. Paul, Badiou shows that even Pascal failed to grasp this in its entirety.

This is analogous to the event of love. A contingent, imperfect other becomes, for us, the site for the love-event. The love-event is birthed from the other, but the lover doesn’t engage in apologetics to defend their claim that their beloved is the most beautiful person in the world. Yet neither are they an apathetic relativist about their beloved. That contingent person who they met through a random set of events becomes the site for that which cannot be reduced to a mere philosophical argument. Something I explore here.

To grasp this means that one can begin to see why some radical political philosophers are drawn to Paul. For Paul is a clear example of a militant who is committed to a truth-event, a truth-event that is based in the world but that is not reducible to it.

This is powerfully portrayed in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. In one particularly incredible scene the firebrand apostle is preaching the resurrected Christ when Jesus confronts him and calls him a liar. When Paul pursues him Jesus says, “I was never crucified, I never rose from the dead. I’m a man like everyone else.” In response to this news Paul retorts, “I don’t care if you’re Jesus or not. The resurrected Jesus is what will save the world and that’s what matters.”

In this scene Paul is faced with the reality that the historical claim that birthed his vision of a universal community (of neither Jew nor Gentile), is false. But rather than despair he thanks Jesus. For he knows that the event is what counts. The historical claim opened up the way for the event, but the event is what counts.

In the same way, a person transformed by love, but who later finds out that their lover was a scoundrel and a fraud, can still be faithful to the transformed life that arose from the love.

For Paul there is probably as little doubt about a historical resurrection than there is doubt for us about the gas chambers in Nazi Germany. But the resuscitation of a body is not what Paul is concerned about: he proclaims Resurrection (with a capital “R”). This means that he proclaims New Being.

Whether one thinks that the historical site of the event is actual or not, one can be caught up in the event and committed to fighting for the universal community that is opened up by the event.

So then, for people like Badiou, Paul provides a great ancient example of what we so need today, a figure committed to fighting for a universal community. A figure who doesn’t get bogged down in modernist apologetics or in postmodern relativism.

March 25, 2015

Confronting the End of Meaning: Crucifixion and the Critique of Signs and Wonders

Last night Tony Jones had a launch for his latest book Did God Kill Jesus. The book itself is an excellent and very readable overview of the various ways that the church has understood the meaning and significance of the Crucifixion. Partly motivated by Trip Fuller’s statement, “God has to be at least as nice as Jesus,” he goes further than simply describing the basic approaches and endeavours to find a way of understanding the Crucifixion that prevents it being mired in a theology that justifies violence, anti-Semitism, exclusion, and political oppression. In the book he views the incarnation as signifying a fundamental shift in the way God relates to human beings (shifting God from a place of sympathy regarding humans to empathy). The infinite lives into the finite and tastes the existential predicament of human subjectivity. Including condemnation by the law, oppression and a sense of alienation (Crucifixion).

The main problem I have with this approach is that Tony continues to see the Crucifixion as a meaningful event. It is an event that must be integrated into a certain apologetic system. An approach that generates so many of the problems that Tony brings up in the book… how to make an event that seems to defy everything we think of the Absolute, fit with it.

Below I have taken an excerpt from The Divine Magician that outlines a critique of this idea. It begins by referencing a previous argument concerning “freedom from the sacred-object” and closes before I go on to draw the consequences of the position I outline. Both of which are important to the position. But I hope it at least introduces the idea that Crucifixion might operate as a rupture in meaning.

This freedom from the sacred-object also spells freedom from the need to find an overarching meaning to life. Indeed, the apostle Paul directly attacks the idea of Christianity offering a system of meaning in his attacks on what he called “signs” and “wisdom.” Signs and wisdom represent two ways in which we seek meaning. Through either apologetic argument or the occurrence of unusual or unexplainable events, we want to find ways to justify our beliefs.

While the affirmation of signs and wisdom to justify a particular religious position is part and parcel of religious discourse, Paul sets his sights firmly against them when critiquing the Jewish community of his day for seeking the former and the Greeks for wanting the latter,

Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom,but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.

What’s fascinating here is the way Paul sets up the Crucifixion as the very opposite of a sign or wisdom. From the perspective of both, the Crucifixion can strike one as nothing but empty nonsense. Why? Because this method of execution symbolized a divine curse. More than this, the idea of an innocent man, let alone God, being murdered in such horrific terms strikes against the idea of justice, reason, or goodness.

It is a meaningless, absurd, and offensive event, something theologian Paul Hessert picks up in his book Christ and the End of Meaning,

Anyone executed by hanging was seen in Jewish tradition as cursed by God. The sign of such a death was taken as divine corroboration of the administration of human justice. In other words, God was seen as acting in this sign-event to give the victim “what was coming to him.”

As that which runs against the very idea of a sign, Hessert argues that what we’re confronted with is a type of profound offense to reason:

The affront is not merely the case of the ignominious, brutal death of Jesus . . . [it is] to the whole religious outlook that searches for signs. . . . Preaching “Christ crucified” is not merely saying that bad things happen to good people but that God’s approach to us belies our expectations.

In other words, the event of the Crucifixion is actually the very contradiction of our expectations. This contradiction is much more than the liberal concept that the cross represents the idea of a good person being killed because he stood up against injustice. It is rather a direct confrontation of all that we think religion and God is about—it is that which breaks apart “our sense of reality.”

In the scripture passage quoted previously, Paul connects the desire for wisdom with the Greeks and their development of classical philosophy (the “love of wisdom”). The Greeks were not so much interested in signs, but rather with the eternal realm of ideas. They sought an underlying rational structure that would make sense of the passing, decaying nature of the world and render it all meaningful.

The preeminent teachers of wisdom at the time of Jesus were the Stoics. Stoicism was the ancient Hellenistic philosophy that emphasized an emotionally balanced life based upon a will that was in accord to nature, a strong moral temperament, and a deeply rational outlook.

These teachers would often compete with Christian preachers for an audience and argued that behind the chaos of our lived experience there was a harmonious center, an order that could, in principle, provide a meaning for everything. The Stoics saw the brokenness and decay of the world as a type of illusion or temporary condition. While they had a strong moral theory, there was a broad acceptance of the status quo. In this way, Stoicism was able to become the philosophical outlook of the cultural elite in the Roman Empire without actually threatening some of the more barbaric and inequitable practices of the day.

The Stoics would have had little problem in accepting the liberal reading of Christ’s crucifixion as an example of one who faced injustice and suffering with peace and resoluteness. Indeed this Jesus would have fitted very neatly into their worldview.

For Paul, however, there was something much more profound and offensive taking place in the idea of “Christ crucified.” Indeed, Paul was reading the Crucifixion against this stoic vision of Jesus. For Paul, the Crucifixion was that which defied reduction to a sign or system of meaning. As Hessert notes,

“Christ crucified” makes no sense. Instead of linking God to the enveloping rationality that absorbs or even overrides the passing contradictions of goodness, it focuses attention on the contradiction itself. That is, “Christ crucified” is no key to the meaning of life and human events. It is a problem to meaning, a problem requiring explanation.

Hessert notes that the Shoah operates in a similar way within Jewish thought. For the Shoah is that horrific, unspeakable event that ruptures and renders offensive any attempt to make it into a divine sign or element of wider rationality. This is why the term Shoah is often preferred over Holocaust. For the latter is derived from the Greek holókauston, a term that has connections with the notion of religious sacrifice and thus religious significance. In contrast, the Shoah simply means destruction and thus lacks any justificatory undertones.

The attempt to provide a cosmic meaning for the Shoah is not simply misplaced, it is a profound offense. The event stands as an affront to all such strategies. In terms of the European intellectual tradition, the First World War can be seen to act in a similar way. One of the features of this horrific event is found in the way that the war disrupted all our attempts to tie it into some deeper meaning or significance.

It is precisely this connection with meaning, religious or otherwise, that the Crucifixion of Christ cuts against.

Once we grasp this idea of Christ representing a break with signs and wisdom, we can begin to perceive how the actual existing church has fundamentally betrayed the scandal of the Crucifixion, effectively making it into a type of Stoic doctrine that doesn’t challenge our world, but confirms it.

In contrast, for Paul, “Christ crucified” is that event that defies all attempts at being reduced to some system of meaning.

It is a type of antisign that fractures religious signs.

An antiwisdom that confounds human wisdom.

A nuclear event that blows apart all of our apologetic enclosures.

March 24, 2015

Christian Humanist Interview

http://peterrollins.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Christian-Humanist-Profiles-31_-The-Divine-Magician.mp3

Here is an interview I did for the Christian Humanist Profiles podcast. In this interview I talk about The Divine Magician, philosophy and theology

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers