Peter Rollins's Blog, page 20

March 6, 2015

World’s Greatest Dad – No You’re Not

The video below cleverly captures the difference between Idealization and Sublimation. For the Best Man the closing comment made by the Groom is patently absurd, and he’s shocked when people react negatively to this obvious truth being pointed out. From his perspective, the room is full of deluded individuals caught up in the insane notion that they are in the presence of a beauty unlike any other.

They think a goddess stands in their midst.

We could, of course, replicate this logic in the face of claims made by parents that their newborn is the most beautiful in the world, or in response to the child who buys their mum a “World’s Best Mother” mug. In each of these examples someone is making a monumental claim about some poor existing individual. A claim that is obviously false.

It is true that we often idealize people in the way that the Best Man assumes the Groom is doing at the wedding. Take the example of parents who can’t imagine their child doing anything wrong. If their child receives a bad grade, or is told off in school, they get irate and complain that their innocent child is being persecuted. While this might occasionally be true, any parent who can’t imagine their child being anything but an angel, is caught up in a form of idealization. Something that isn’t good for them or their child. Idealization can also be seen in the way that some people are addicted to the “honeymoon period” of relationships. Always beginning a new relationship with a sense that they have found the One, then breaking things off when something doesn’t live up to the hype.

It might seem that the only alternative to idealization is a bland world where parents talk about their child being reasonably attractive compared to other infants, and children buy cards that state, “You’re roughly average in your parenting skills.” But there is also the stance that Freud called “sublimation.” This is where some particular thing/person/cause takes on an absolute value for us, not in wanton ignorance of his/her/its imperfection, but in the very acceptance and even celebration of those imperfections.

In religious terms, if the fundamentalist can be described as one who idealizes their particular religion, then the New Atheist often comes across as the antithesis – utterly bemused at someone investing absolute value into a particular, contingent, historical event.

But the act of sublimation takes a step beyond this binary. It is manifest in the individual who confronts in a particular, contingent, historical event, something of infinite depth and density.

In romantic terms, to idealize a lover is to photoshop every part of them so that they become some reflection of our ideal. An act that does violence to the other, prevents us from relating to them in a meaningful way, and obstructs a healthy relationship.

But the alternative to this act of photoshopping isn’t found in making do with someone who fits our broad categories of likes, dislikes and hobbies. To love involves proclaiming that the one you are with is the most wonderful, beautiful, smart, funny and thoughtful individual in the world… precisely because of their quirky, often bizarre, individuality. In more philosophical language, it is an affirmation of the Absolute that doesn’t wipe away the Particular, but rather that finds the Absolute in the very affirmation of a Particular in its very particularity.

March 3, 2015

The Faculty, Belfast, NI

I’ll be giving a lecture in The Black Box called “God is Undead: The Religion of New Atheism”

Nietzsche once proclaimed that God was dead. But he also noted that the shadow of this dead god remained fixed on the wall of secular culture. Unlike people who celebrated the decline of church life, he claimed that the most vocal despisers of religion were actually still far too religious. While people might have let go of God as the means of finding wholeness, meaning and harmony, they were still trapped in the gravitational pull of these ideas. They were still evangelists, preaching the good news that ones religious impulses could be satisfied in the market place. One sovereignty simply replaced by another. In this lecture Belfast born, LA based writer and philosopher Peter Rollins will use psychoanalytic theory and existential philosophy to critique the prophets of New Atheism for not going far enough. Instead he will propose a more far-reaching and truly disturbing vision.

More information to follow

February 27, 2015

God is Unconscious: A New Book by Tad Delay

My friend Tad Delay has just published a great book called God is Unconscious that explores Lacan’s psychoanalytic work in relation to theology. For those interested in the intersection of psychoanalysis and theology, or with understanding more about my own use of Lacan, I’d warmly recommend the book. Indeed I liked it so much I write the forward to it, which I’ve reprinted here

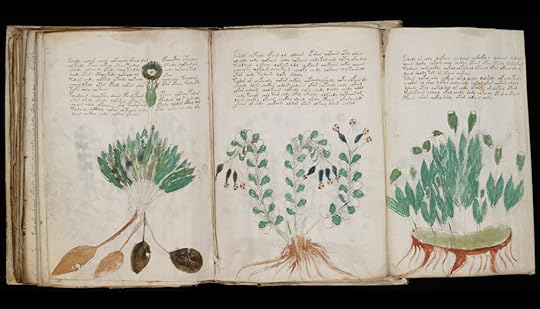

In 1912 a Polish book dealer named Wilfred Voynich purchased a mysterious manuscript thought to have been composed in Northern Italy during the Italian Renaissance. The manuscript itself was an obscure, esoteric script composed of approximately 35,000 “words,” spread over 240 pages that comprised six sections.

What gave the document its mesmerizing appeal was quite simple: it was a carefully crafted text full of illustrations that no one could understand.

The Latin-esque markings appeared to obey a crude grammar and syntax, yet these seeming signifiers roamed free, defying any stable link to a signified. The Voynich manuscript, as it became known, quickly established itself as one of the most interesting enigmas in cryptography, with experts discussing whether the author was a cryptographer, charlatan, outsider artist, mystic channeling glossolalia, or some poor scholar suffering from a brain trauma.

Like Hopelandic, the invented “language” of Icelandic band Sigur Rós, The Voynich Manuscript easily evokes a feeling of meaning, yet this meaning is frustratingly experienced as simultaneously eroded. Something seems to be said, yet this said remains too ethereal to grasp.

Reading Lacan can often evoke the same feeling one gets when encountering The Voynich Manuscript, and similar claims have been made about the former as those concerning the author of the latter. Alan Sokal, for example, claimed that Lacan’s use of science is utterly nonsensical, while Noam Chomsky has referred to him as a self aware charlatan. For some Lacan is dismissed a master huckster blessed with a gift that enables him to fool some of the smartest people in the room, while for others he’s hailed as an indispensable guide for those grappling with the complexity of human subjectivity and the ideological systems which this subjectivity invents/inhabits.

Yet, just like The Voynich Manuscript, Lacan’s work has, in its resistance to easy interpretation or reduction to a University Discourse, generated a significant industry of academic production. His work continues to have a profound impact in critical theory, and has been put to use in all manner of fields from literary studies, feminism, and film theory, to jurisprudence, linguistics, and philosophy. His teachings have not only been productive in generating new concepts and distinctions, but has provided ways of challenging the very frame these disciples use to approach their respective areas of inquiry. The harvest produced by his work is thus found well beyond the field of psychoanalytic practice it was cultivated in. Even for those who wonder whether Lacan’s work is meaningful, it cannot be denied that the work is ripe for meaning making.

One of the disciplines that one would expect to have been impacted by the industrious work of Lacanians is that of theology, if for no other reason that Lacan himself often used theological references, quoted theological thinkers, and commented upon a link between the Protestant Reformation and the psychoanalytic revolution. Yet this has, with a few exceptions, not been reflected in the literature.

This situation has been changing in recent years with a new generation of thinkers – partly inspired by Žižek’s theological investigations – reflecting on Lacan’s corpus with religion in mind. With God is Unconscious Tad DeLay has boldly entered this fray with an important contribution that offers clear co-ordinates with which to navigate the landscape of Lacan’s teaching while also preserving his unique voice.

Providing clarity while maintaining Lacan’s voice is no easy accomplishment. To err on one side risks turning Lacan’s writing into a series of hackneyed sayings, while erring on the other runs the danger of providing a map as baffling as the landscape it outlines.

DeLay avoids these pitfalls by providing a brilliant overview of Lacan’s work that is disrupted by a wealth of quotes. These quotes are not domesticated by his interpretations, but are set alongside his reflections to challenge, deepen, and enrich them.

DeLay provides the reader with a powerful overview for those standing on the threshold of Lacan (which includes those who have read him many times before), but he also puts Lacan’s corpus to theological work. More than this he demonstrates how Lacan’s teaching impacts the work of theology. This is not a book that mines Lacan’s text for explicit theological references or themes, rather it shows how Lacan’s overall project disrupts, deepens, and challenges the very field of theological inquiry. DeLay takes seriously Lacan’s claim that psychoanalysis and theology are closely linked and draws this out in ways that are clarifying and fruitful.

DeLay has spent years with Lacan’s teachings. He has sat with them, worked through them, and let them speak into him. The fruit of that labour is what you hold in your hands, an insightful and fertile text that will prove invaluable for those who wish to grapple with Lacan seriously and theologically.

Those who have spent years traversing Lacan’s texts will tell you that endurance is required. It’s hard to avoid periods of frustration while reading Écrits or confronting confusion when working through the Seminar. Yet countless people have found their labors rewarded by points of clarity, insight, and productive association. Which brings us to a second requirement: guides to help encourage you and draw your attention to what might otherwise be missed. In God is Unconscious DeLay proves to be such a guide. He doesn’t do all the work for us, masticating the food so that we might swallow it without the effort or the taste, but instead he helps make the formidable material more palatable so that we might experience how nourishing it really is.

February 24, 2015

Imago Dei, Peoria, IL

I’ll be speaking at two morning services in Imago Dei - 8:30am and 11:15am - and then doing an evening event in the Fox Pub in Peoria at 7:00pm (doors open at 6:00). I’ll be joined by local artist Jared Bartman, who’ll be providing music. Tickets are available for purchase here ($8 in advance / $10 at the door). There is a limited quantity, grab them while they last.

For more information click on the link

City Life, Peoria, IL

I’ll be speaking at two morning services and then doing an evening event. More information to follow

Christianity in Its Properly Irreligious Form: An Interview

This is a little interview I did for Aslan books exploring the themes of my book The Divine Magician.

What was your aim in writing The Divine Magician?

One thing that both the critics of religion and its defenders seem to agree on concerns what Christianity actually is. To paint with broad brushstrokes, they agree that it involves a belief in God, the idea that we can reconnect with this God, and the notion that this reconnection will re-establish a lost harmony. The former attacks these ideas, the latter defends them.

In contrast, The Divine Magician presents a radically different reading of Christianity. One unconcerned with what people believe, that is not about reconnecting with some ultimate source, and that is most certainly not caught up in re-establishing a lost harmony. What people will find within the pages of this book is an unapologetically this-worldly reading of Christianity, one that views the subversive heart of the gospels as nothing less than an insurrectionary invitation to become a cultural dissident who challenges the status-quo, embraces the world and has the audacity to embrace freedom.

To use a somewhat old-fashioned expression, it is an existentialist approach to Christianity that finds itself at odds with both the religious authorities and their cultured despisers. This book is the culmination of a project I’ve been working on for some time. It is a book that signals my clearest and most forthright attempt to articulate the good news of Christianity in its properly irreligious form.

Is it important, in your view, to establish the roots of Christianity as an historic event?

I approach the early writings of Christianity in much the same way as a psychoanalyst approaches a dream. The analyst takes the dream of their analysand (the one in analysis) literally; to the letter. In this way I am a type of fundamentalist.

For an analyst, the dream of the analysand is a type of portal into the Real of the dreamer, and thus offers a way of uncovering the deep, disturbing, and potentially enlightening truth of the subject. The analyst doesn’t concern herself with matching the dream with actual events, but works hard to excavate the reasons why various events impressed themselves upon the dreamer. Ascertaining whether or not something in a dream resembles an objective happening in the world isn’t important for the analyst. Indeed the analyst doesn’t even have the means to decide such things anyway. Rather the analyst is there to bear witness to what is spoken, to let the dream unearth a hidden desire, to break open dry and brittle ground. For me, the role of the theologian proper – not what passes under that name today – is to help their community encounter something of their truth through a careful analytic listening of their text.

What place is there in your proposition for the Mysterium Tremendum et Fascinans? It seems from your opening chapter that you would discount the idea of God as ineffable; is this a fair conclusion?

While I briefly wrote in the register of the apophatic, and maintain some sympathy with its more marginal figures, my work ultimately offers a critique of mysticism.

As I touched on in the first question, Christianity as we understand it today is related to the idea of re-establishing connection with a lost wholeness, an original blessing. This is either described in terms of bridging a separation (God is a being who we are distant from) or overcoming an estrangement (God as the Ground of Being which we are alienated from). But either way Christianity takes the lacking, finite, desirous subject and (in this life or the next) plugs them back into an originary source of plenitude.

For me mysticism ultimately offers the vision of a return to God as the Ground of Being. While there are some notable exceptions, the theory and technology of mysticism is thus largely caught up in the idea of a sacred-object that promises wholeness. My work is purposed with the task of critiquing this sacred-object. Rather I’m arguing for a materialist reading of Christianity that invites an individual into an acceptance of lack and a warm embrace of the incomplete. This is not a solemn theology of the heavens (which, I argue, always ends up in hell); it is a celebratory theology of the earth.

You talk of Churches needing to do more than simply accept ‘scapegoated’ groups (e.g. Women, LGBT etc), but to move beyond the idea of the ‘other’ that threatens them. How could this be achieved?

In the book I try to show how the scapegoat mechanism is inherently linked to the idea that there is something that brings wholeness and fulfillment. When these are not attained the temptation is to blame something; to make something carry the failure. The scapegoat mechanism is what results from not being able to bare our own longings, fears and anxieties. This is the hell that sticks indissolubly to all heavenly visions.

I see the answer to this problem nestled in the insight that the poor will always be among us. There is a lack, a poverty that marks us as humans, a poverty that we either learn to own, or place on other people’s shoulders.

In The Divine Magician I paint a picture of a community living this personal/communal ownership out. A community that has forged tools that help people confront, and tarry with, their darkness. Under the banner of Transformance Art I explore how comedy, song, poetry, prayer, preaching, and parable can help in this difficult work.

Is there a place left for the creeds as a statement of faith?

Perhaps a good way to approach an answer would involve considering how we think about and enact love. Every society has different ways of expressing what love looks like. Indeed, even within a single society, there are numerous subcultures that express love in ways that diverge from the norm. Communities will collect their different ways of understanding love in forms of communication like poetry, painting and song. Yet the love itself is not captured in these concrete reflections. One can recite the poetry or sing the songs without knowing the love that conceived inspired their creation. Without the concrete expressions we would have no way of speaking the love, but the love is not spoken in the expressions.

In The Divine Magician I write about how faith represents a way of experiencing the world. One in which we feel the surface infused with infinite depth. I am careful to point out that this is an experience that does not relate to ones intellectual beliefs. Different communities will have different ways of verbalizing what living with this sense of infinite depth actually looks like, and those verbalizations could be seen as that communities creeds. But these creeds are temporary shelters, contingent resting places, not eternal citadels. The creeds of a given community are an expression of the way that that community conceptualizes a life they feel caught up in. That concrete expression is always deconstructable but, to borrow a turn of phrase from the philosopher Derrida, what inspires it is undeconstructable.

How do the ideas in the book translate into a practical approach for preachers, priests and lay-members?

While I’m deeply interested in the theory of what I call pyrotheology, my passion is in the technology that arises from it. The technology being the various practices that result. As such my primary interest is in exploring what might be called “microsocieties of resistance,” small subcultures that embody a different type of life to the one expressed by contemporary society. Microsocieties marked by the fact that they aren’t caught up in the frenetic pursuit of some sacred-object.

For me the actual existing church often resembles a type of nightclub where people go to get high, listen to escapist music and find respite from their troubles. In the same way many churches help people get high in the uplifting music, prayers and sermons. The problem however is that the problems that are briefly repressed don’t go away, they return once the high has worn off, so one has to keep going back.

In contrast I encourage church leaders to create spaces that more closely resemble the type of bar found in small Irish towns. A welcoming place where an atmosphere is created that encourages people to have a drink and actually chat with their friends about their week, with all of its joys and woes. Instead of deafening music designed to block out too much reflection, you’ll find some musicians in the corner singing beautiful traditional folk songs reflecting the full range of human emotions.

Songs about love and loss, life and death, sad endings and new beginnings.

Songs that somehow help you confront your own personal issues in a way that makes the burden lighter, easier to carry.

My point in using this analogy is to show that the opposite of creating a space that encourages you to run from your suffering isn’t the construction of some dure, melancholic cell. But rather the creation of a rich, fun, communal space where people can genuinely encounter others, feel less alone and gain strength for their trials.

What do you hope people will take away from The Divine Magician?

I believe that this is my clearest attempt yet at articulating a radically different type of Christianity to the religious one we are bombarded with today. An understanding that blurs the lines between theists and atheists, that is not concerned with the embrace of a particular worldview, and that doesn’t demand allegiance to some single cultural, political or religious identity. This is a Christianity that embraces the grit and grime of the world, that says “yes” to doubt, complexity and ambiguity, and that proclaims a loud “amen” to life.

I want this book to give words to those who are already wonderfully lost in this alternative, irreligious Christianity. I want it to encourage them that they are not alone in their pilgrimage.

The path that The Divine Magician describes is not an easy one to walk, and I’ve known many who’ve lost friends, jobs and more as a result of taking it. Hence I feel a little hesitant about recommending it. But it also attempts to reflect a path that I passionately believe is enriching, life affirming and transformative.

To finish with one last analogy, we are like haunted houses, each and every one of us, full of ghosts that we’d rather not face. Authorities in both the sacred and secular camps offer us all manner of distractions to help us avoid confronting our ghosts. But whatever we do during the day, the specters come out at night. In this book I encourage the reader to face their ghosts rather than turn from them, not so that they might die of fright, but so that they might learn from them, be transformed by them and perhaps even be freed from a few of them.

February 7, 2015

You Don’t Need to Be an Atheist to Be a Christian

Central to my recent work is the claim that Christianity – in its subversive, evental heart – expresses the death of the Big Other. More than this, I argue that to “be” a Christian means producing/undergoing/tarrying with this death.

The question then concerns what the term “Big Other” actually means. For instance, is this simply another, more specialised, way of signifying God or theism?

Is the “death of the Big Other” just a cryptic way of saying that the fundamental Christian experience is the embrace of atheism as found in people like Dawkins, Dennett and Harris?

While the term “Big Other” has some crossover with the idea of God as popularly understood, I want to draw out how it differs.

If the death of the Big Other simply meant the end of theistic belief, then Radical Theology would side squarely with the New Atheists. Yet Radical Theology sits just as uncomfortably with New Atheism as it does with contemporary religious belief. Indeed, in its new guise, Radical Theology might prove to be more of a thorn in the side of the cultured despisers of religion than it is a pain in the neck of their disdained target.

While the term “Big Other” does cover much of what goes under the name of religion, it also covers much of what goes under the name of the secular. If it is synonymous with theism, then it is a seemingly surreal form of theism that is alive and well among those who proudly proclaim they don’t believe in God.

So how can someone believe something that they sincerely say they don’t believe? To grapple with this it’s helpful to think about what happens in the psychoanalytic clinic. It is not uncommon in such an environment for someone to be suddenly confronted with a belief that they were not conscious of, or even adamantly denied,

My mum wants to kill me

Men hate me

I am disgusted with myself

In such moments the individual speaks something that has been making itself know in the texture and timbre of their life, without ever being acknowledged. Like the proverbial devil whose greatest trick was to convince people he didn’t exist, such beliefs are all the more powerful in not being acknowledged.

For example a woman might come to see that her distain of a particular colleague is directly related to the way he reminds her of her dead father. It might take years before she realises that she has an unresolved anger toward her father that is negatively affecting her relationship with her colleague.

In situations like this the individual is directly confronted with an unconscious belief manifested in certain behaviours, yet unrecognised at a conscious level.

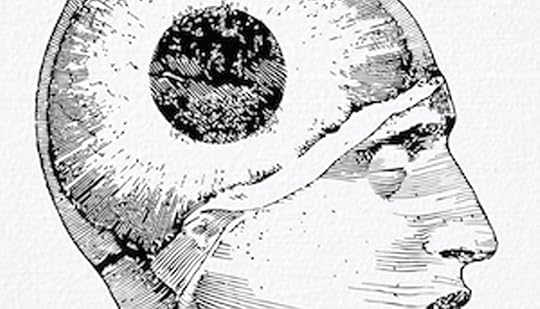

In Lacanian psychoanalysis the “Big Other” refers to a type of internal judge that begins to form around the age of six months. In general it is not something that one is directly aware of, but it remains influential in much the same way that a person might not believe in ghosts, yet still be scared of them.

Without getting too caught up in the specifics of what the term means in psychoanalysis, its theological significance relates to the, often unconscious, belief in some Thing that will bring wholeness and overcome anxiety. A Thing that is reflected in an infinite variety of concrete things: from having a child or winning a race, to completing a collection of magazines or being invited to the right party.

Like psychoanalysis, the theological “cure” involves draining this Big Other of its power.

This means that the Radical Theology I espouse and develop under the name of pyrotheology is involved with the death of an idol (that object which stands in for the forever elusive, non-existent Thing) that operates in many forms of both theism and atheism.

Occasionally a theorist will use the term “theism” in place of the “Big Other.” For instance, one might hear a (Lacanian) psychoanalyst say that one only needs psychoanalysis insofar as one still believes in God. While some do very closely relate the popular notion of theism (as referring to belief in God) to the Big Other, the latter ultimately relates to the reign of an unconscious Sovereign power that is not necessarily connected to a conscious belief concerning the existence of a First Cause.

My recent trilogy of books (The Divine Magician being the last of the three) is concerned with the theory around this death of the big other as well as the technology concerning how we might enact it. You can also hear me speak a little about this subject here.

For those who wish to delve a little deeper into these difficult waters, my good friend Tad Delay will be publishing an excellent book in the next few months –God is Unconscious – that will serve as a useful map for the perplexed.

February 3, 2015

Saint Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, Antioch, IL

Join me at Antioch Episcopal Church for an entertaining evening of theological reflection starting at 7pm. The talk I’ll be giving is called Forgotten, but not Gone: Confronting the Hidden Truth. In it I’ll be offering a reading of the Christian faith that invites us into a celebration of doubt, complexity and ambiguity. While we sometimes conspire with religious institutions in an effort to forget our brokenness and cover over our questions, I’ll attempt to will us how Christianity, at its most subversive, invites us to face those parts very things as a means of entering into a more vibrant, healthy and loving type of life.

The evening costs $20 and seating is limited. There will be a little food provided. Call 847-395-0652 to reserve seats, or email the church here.

Antioch Episcopal Church, Antioch, IL

Join me at Antioch Episcopal Church for an entertaining evening of theological reflection starting at 7pm. The talk I’ll be giving is called Forgotten, but not Gone: Confronting the Hidden Truth. In it I’ll be offering a reading of the Christian faith that invites us into a celebration of doubt, complexity and ambiguity. While we sometimes conspire with religious institutions in an effort to forget our brokenness and cover over our questions, I’ll attempt to will us how Christianity, at its most subversive, invites us to face those parts very things as a means of entering into a more vibrant, healthy and loving type of life.

The evening costs $20 and seating is limited. There will be a little food provided. Call 847-395-0652 to reserve seats, or email the church here.

January 25, 2015

Putting Institutions on the Couch: Psychosis, Perversion and Neurosis in Religion

For some time now I’ve been drawn toward the area of structural psychopathology. One of tools I’m finding insightful is the diagnostic system used by Lacanian psychoanalysts. Unlike the DSM, where one can get lost in the ever expanding forest of new “disorders,” Lacanian’s make use of a foundational system that isolates three fundamental positions that reflect the underlying way an individual deals with lack,

Foreclosure (Psychosis)

Disavowal (Perversion)

Repression (Neurosis)

These three positions have further subdivisions, and the ways that they actually manifest themselves is as varied and complex as the human who exhibits them.

I won’t be offering an overview of these three positions in this post, but if you’re interested, there’s an excellent book by Bruce Fink called A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis.

My interest, largely inspired by the work of Slovoj Zizek, involves putting this conceptual matrix to work as a means of helping to diagnose, and formulate remedies for, destructive political/religious structures.

Take the example of a psychotic structure like paranoia. Paranoia refers to a thought process in which the individual is locked into a delusional and irrational framework.

It is manifested in symptoms that include deep feelings of persecution, a tendency to distrust others, the making of false claims and the attributing of evil intentions to random people or events. Intense suspicion, mistrust and hypersensitivity are found alongside a hyper-vigilance that seeks any and all details that might solidify the persecutory delusion of the individual or confirm an existing bias.

Those suffering from paranoia are generally very easily offended, quick to divide the world into good and bad, hold tightly to any perceived wrongdoing against them and exhibit an often overwhelming sense of personal rights. The totalising logic found with those suffering from paranoia can be characterized in the following way,

All doctors are out to get me

But this doctor has gone out of her way to help you

She’s just doing that to fool you

The individual will often go to extreme lengths to solidify their delusion. As a result paranoid individuals will tend to exhibit an obsessive commitment to observing people they take to be a threat, expending vast amounts of energy looking for anything that might confirm their narrative or be taken as a slight.

Unlike neurosis, which is linked to feelings of doubt, psychosis (like paranoia) is characterized by a strong sense of certainty.

One of the reasons why this behavior can be so destructive for the individual lies in the fact that their symptoms make it difficult for them to make and sustain healthy relationships. They often remain single, have few friends, and break relationships over small disagreements. Beneath the paranoia one often finds a person who is suffering from deep anxiety, childhood trauma, depression and a sense of helplessness.

To give a concrete example, I have an acquaintance who exhibits an acute sense of paranoia. This manifests itself in the fact that figures of authority are generally distrusted and seen as hostile. The result has been destructive for both her (when going for cancer treatment she moved around various doctors, believing they were patronizing her, hiding information, or wishing her ill) and her children (she has removed them from various schools, believing that the teachers were persecuting her kids). Anyone attempting to challenge her, including her closest family members, are taken to be part of a grand conspiracy against her and viewed with suspicion. The result, as you might expect, has been a life increasingly marked by isolation and withdrawal from others.

An important theorist in helping us understand paranoia is Melanie Klein, whose insights into the way that a Paranoid-schizoid position is evidenced in infants is invaluable.

Currently I have a strong interest in how communities inhabit psychotic, perverse and neurotic positions. In terms of the example above concerning paranoia, it is easy to think of fundamentalist communities, but we also see it in communities forged around promoting and protecting conspiracy theories like the Apollo 11 mission being a fake. Here a group exhibits all the hallmarks of individual paranoia: certainty, distrust, false claims, attribution bias, isolation, delusion etc.

By reflecting on literature dealing with psychopathology we can become better at identifying, responding to, and helping communities that are engaged in destructive behavior.

For instance, to approach a community that exhibits a psychotic position as if it were neurotic, can be counterproductive. When dealing with a neurotic, an analyst must help them listen to their unconscious. They do this by subtly introducing the neurotic to the reality that they are communicating things that they are not aware of. For example, one might listen to a neurotic talk about the anger he feels toward his partner. At a key point the therapist might intervene in the discourse to suggest that the anger might actually reflect a frustration he has with his dead father. If this is a productive interpretation, the analysand will feel a moment of insight that leads to the opening up of new material. The neurotic was communicating something in his anger that he wasn’t really aware of, yet somehow also knew (because he recognized it when it was suggested). This is repression in action: the pushing out of consciousness something unpleasant or traumatic.

In contrast, someone with a psychotic structure doesn’t, strictly speaking, have an unconscious to confront. For the unconscious is produced by repression. The psychotic means what they say. There is no hidden meaning, no secret uncertainty or ambiguity. To try and get someone who is psychotic to experience ambiguity of meaning can actually lead to a psychotic break. When this happens the ambiguous other meaning is felt to be something threatening that is coming from the outside (rather than something that is a part of them).

A leader within a psychotic structure won’t find much success in trying to introduce doubt and ambiguity. Indeed this will likely be read as a threat to the structure, and the individual will soon get in trouble.

In closing it is worth making a couple of additional points. Firstly, while we might think that all psychotic structures are bad, this is not the case. There are plenty of fundamentalist communities that are not destructive. They exhibit things like certainty, isolation, and a tendency to view the world as hostile. But have found ways to mitigate against the destructive symptoms that often accompany psychosis (Amish communities might be an instructive case in point). Secondly, being within a psychotic, perverse or neurotic structure doesn’t mean you reflect that at a subjective level. It simply means that you are placed/have placed yourself in a position that encourages certain actions associated with those positions.

In the coming year I’ll be coming back to these themes both in the blog and in my next book.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers