Peter Rollins's Blog, page 17

June 1, 2015

It Spooks Launch Party, Los Angles, CA

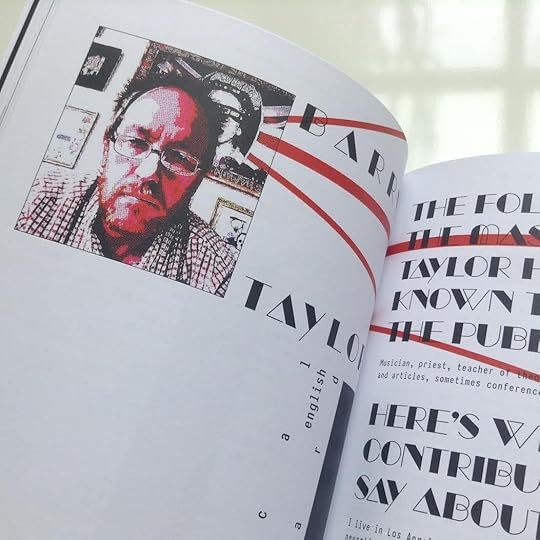

Join Erin Schendzielos, Barry Taylor, Tad DeLay and myself as we celebrate the launch of the beautiful full-color version of “It Spooks.” In addition to talks and conversation there will be refreshments and a chance to buy the book. It really is a unique and powerful piece of art. We will be meeting at 11:45 343 S Church Lane, LA, 90049

Click here to see pictures of the book

May 27, 2015

The Chapel of Negation: Some thoughts on Pyrotheology

One of my favorite spaces is the Rothko Chapel, hidden away in a largely suburban area in Houston. The chapel itself houses fourteen large black, color hued, canvases painted by Rothko shortly before his suicide in 1970.

This sparse, void-like space, dominated by Rothko’s stark work invites the individual into an experience of a radical negation. Looking at the huge canvases hung on the cold slate-coloured walls, its hard not to feel that this is a chapel dedicated to the Nothingness. As such is seems to offer us a desert-like wasteland nestled in the oasis of being and having.

The Chapel is a type of non-place that coaxes us into a place of unknowing. It thus provides a solemn welcome to anyone willing to connect with the lack within their religious, political and cultural situation.

What Rothko helped to create in this Chapel is an artistic expression of what it might mean for us to gather around a shared lack.

What’s interesting however is the way that this profane space that negates all faith traditions was quickly turned into a “sacred” space that affirms all faith traditions. The Chapel itself has effectively become a place where people of different religious backgrounds can come together and seek out some shared positive force.

It is this move from a placeless place where we join together in lack, to a location where we seek to unite around an abundance, that charts the temptation we face to bind together around the desire for some underlying, frictionless harmony rather than remain together in the felt loss of that harmony (acknowledging that the felt loss is a fiction born of human subjectivity).

The project of pyrotheology involves an acknowledgement of this lack in the various ways it manifests. It encourages an ongoing sacrifice in which we burn away all the idols of positivity we construct. It represents a subversive approach that encourages the sacrifice of what we think will give us ultimate pleasure: a sacrifice that is done precisely in the name of enjoyment and fulness of life.

Pyrotheology is thus similar to what John Caputo describes as a Radical theology that haunts Confessional theology. Radical theology is here not understood as a positive position with its own dogmas and doctrines, but rather as a specter that continues to spook dogmas and doctrines, breaking them open to ever new possibilities.

Pyrotheology utilizes various methods to encourage the creation of communities that not only recognize the lack at the core of our various positions, but to celebrate the insurrectionary power of that lack and uncover its liberating potential.

Key to the approach I’m trying to develop is drawing out how the acknowledgement of this lack can actually lead to a deeper, richer enjoyment of life. This is a type of transgressive enjoyment that is able to live with the acknowledgement of death and decay. As such it can free itself from any world that promises us an escape from such things through prayer, property or pharmaceuticals. Like a sun that burns bright in the very act of burning up, so we can learn to expend our energy in worthwhile projects that might end up being the death of us.

May 19, 2015

Joined By Our Lack: On Sacrifice, Pyrotheology and Burning Man

At a Homebrewed event recently my friend Bo Sanders made a comment that he felt pyrotheology wasn’t substantive enough. In this post I want to offer a brief response. One that I will be elaborating on in future talks and writing.

For the theorist Lacan our entry into subjectivity is structurally similar to the situation in which a robber surprises us in an alleyway and shouts, “your money or your life.” Either we give the robber our money (depriving us of a material we can use to bring pleasure), or we refuse and lose the capacity for having any pleasure whatsoever.

To gain ones life (rather than keep it) we must accept a separation from the environment we are dispersed within, and this separation is experienced as a fundamental loss.

Our entry into the world is marked by a sacrifice. If we refuse this sacrifice we do not properly enter the world (psychosis being one of the results of this refusal). This sacrifice that is necessary for the birth of the subject gives rise to a fundamental deception, something I’ve explored in The Idolatry of God. Basically, the deception comes in the form of thinking that there is something we have sacrificed. Instead of realizing that the sacrifice is an original gesture that gives birth to the subject, we imagine that we were already a subject that sacrificed something.

In psychoanalytic terms the experience of sacrifice gives birth to the idea that there was something we sacrificed, something we might be able to get back or recreate. But this is a fiction: the sacrifice comes first and then gives us the impression that something was given up. The sacrifice actually generates a gain rather than a loss: the emergence of the human subject.

It is difficult for us to accept this fundamental sacrifice and realize that there is no exception to it (that neither we, nor anyone else can avoid it). If we cannot accept the universality of this sacrifice we are caught up in what Lacan calls “masculine logic.” This is where we think that there is some exception to the rule, some individual who has the full pleasure that we lack (what can be called the “non-castrated other”). This idea generates all kinds of jealousy, aggression and conflict. In other words, we tend toward thinking that there is something in the realm of technology, pharmacology, politics or religion that can abolish the sense of loss we feel. In fantasy we construct a narrative that makes sense of our fundamental loss and postulates a way to rid ourselves of it.

One of the interesting things about this theory is the way that it points to the idea that what makes us human, and joins us together, is a sense of lack. All manner of problems arise when we fail to acknowledge this. We find ourselves thinking that there is some other who lacks this lack, we fight to achieve wholeness, or we pretend to ourselves that we already have it. But all of this just obscures the universality of the originary loss, the loss that we all share. If we are able to accept that there is no non-castrated exception to the rule then we can locate an enjoyment in a form of life that is not frantically seeking an imaginary lost object.

What I took from the criticism at the Homebrewed event is that the type of Radical Theology collective I advocate is constructed on loss. That it celebrates destruction without construction.

But my response is that this is exactly the point. To grasp this we should reflect on how joining society involves a repetition of the fundamental gesture that makes us human. It involves accepting a type of sacrifice in which one submits to certain rules and regulations in the knowledge that everyone else has to do the same. It is this sacrifice that generates the temptation to fantasize about a primordial life of pure pleasure that exists outside this world of rules and regulations. It generates the fantasy of some non-castrated other who doesn’t play by the rules and thus fully enjoys while we struggle on. A fantasy that is created by the very entry into society. Here one only has to think about the type of villain encountered in James Bond movies. An individual or group that exists as an exception to the rules, that enjoys fully outside the constraints that restrict us. We both love the villain and hate them, finding pleasure in identifying with their full enjoyment while wishing for their demise. After all, why should they get the pure pleasure withheld from the rest of us.

To construct communities that revolve around gaining that which we feel we have lost (the impossible object that is experienced as merely a prohibited object) means that such communities will always be plagued by conflict, disappointment and frustration. For the prohibited object will always elude the community (after all it is a fiction sustained only by our sense of its loss). This constant failure will need to be repressed or blamed on some person or group, whether that blame is externalized onto an outsider or internalized in a form of self-hatred.

So is it possible for a community to be formed around the celebration of pure sacrifice without needing to place this within a wider matrix of ultimate gain?

One community where this seems to exist is Burning Man. While the festival itself is awash with the promise of nirvana either through new age practices or pharmaceuticals, the main drive of the event is a pure expenditure through sacrifice. Huge structures are built and then burned down for no explicit return. Something that requires a huge expenditure of resources.

While other forms of sacrifice – from religious murders to political wars – are justified via an end goal, Burning Man is a temporary collective bound together by a pure loss. From what I’ve heard the festival was initially born from a burning ritual done by a heartbroken young man. This act of destruction was then shared by others, and continued to grow into its current form.

Christianity can also be seen as a community formed around a shared loss: the death of God. The prime sacrament of the community is Communion, a ritual in which the community is joined, not in sharing a gain, but in a loss. Of course, this has been rendered into the ultimate positivity. The religious sacrifice is interpreted as offering the ultimate treasure (and thus is not a sacrifice in the proper meaning of the term). One enters into an exchange in which a small loss is viewed as actually cashing out in a huge gain: everlasting life, unending joy, divine justice, punishment of enemies etc.

In pyrotheology the sacrifice embraced by what we might call a “Collective of the Death of God” is not a preliminary stage in the journey toward some ultimate positivity. But neither is it a community of despair. Rather the death is a birth.

The sacrifice is generative.

It generates a community no longer enslaved to the masculine logic of the constitutive exception that we can never touch. This enslavement is viewed as nothing but a lure that leads to frustration and desititution. The Radical Theology collective offers the possibility of a type of community caught in what Lacan called the feminine logic. This is where pleasure is no longer deferred onto some future state (we’ll get it back one day), on distanced by being placed onto some other person (they have the pleasure that I want). Instead we can gain an enjoyment here and now in the act of sacrifice itself. It must however be acknowledged that there will always be a pull toward reinscribing meaning into such communities of loss.

May 13, 2015

You Can Fulfill Your Dreams… Just be Prepared for the Abject Horror

In a previous post I contrasted neurotic, psychotic and perverse political strategies to a psychoanalytic approach that attempts to help people realize their fantasy in reality (rather than in a retreat from, or protest against, it). The problem here, as Todd McGowan points out, is that the political potential of psychoanalysis can start to sound like a sophisticated form of the motivational poster that asks us to fulfill our dreams. This however fundamentally misses the truly subversive politicial potential of the discourse.

In order to gain a better understanding of the relationship between fantasy and reality in psychoanalysis (which is a large subject) we should first consider how the realization of the fundamental fantasy in an individual’s social reality is actually traumatic to the subject rather than joyous.

The reason for this stems from the idea that our basic fantasy is a type of lie we tell ourselves in order to cover over the trauma of an originary loss. To directly realize ones fantasy (rather than simply achieving some practical goals) means confronting the deception of the fantasy and thus feel the tremor of an inner lack it covers over. This can be described as a type of failure that is hard baked into the very heart of success.

The success of achieving ones fantasy is ultimately a failure insofar as one perceives their desire as connected to the object that the fantasy aims at. For instance, if one directly fantasizes about becoming a millionaire, then achieving the goal exposes, at a subjective level, how the true function of the fantasy is precisely to keep one from achieving its aim, so that one can keep the fantasy alive. The goal posts must thus be changed by the individual in order to keep the fantasy (and the function of the fantasy) alive. If this doesn’t happen the individual can suffer from a breakdown.

In psychoanalytic theory one of the reasons for confronting our fundamental fantasy is not so that we can better “achieve our goals,” and find fulfillment, but precisely so that we can confront the lie of our fantasy.

The point is not to do away with fantasy, but to try and change the relationship we take up in relation to it. The new relation is one that doesn’t locate the pleasure of the fantasy in achieving it, but in directly assuming the fantasy regardless of fulfilling it. The individual realizes that the goal of fantasy is not in its being swallowed up in some final victory, but is concerned with keeping our desire alive.

Politically speaking, this means that we engage in a certain cause without deferring our pleasure to the point when the cause is achieved. This approach does not simply drain the pleasure out of fighting for the cause in the moment, but it also ensures that any ultimate success is experienced as a type of subjective failure or destitution.

Instead, we must try to reposition ourselves so that we can directly enjoy our commitment to the cause itself; learning to directly embrace it as an end in itself. To do this means that we give ourselves to it in a mode of action outside the realm of economic exchange. From the position of rational calculation this can seem like a form of madness, for if we embrace our cause as an end in itself we might end up giving ourselves to seemingly lost causes.

This is one of the lessons we might take away from the Norse gods. From what I’ve been told (I’ll need to do some research to check), some clans would follow Norse gods destined to defeat. If this is in fact the case, then it gives a powerful expression of the approach outlined here. Namely, that we pursue our highest goal regardless of the ultimate cost or outcome for the pleasure is found in the commitment itself.

Take the example of environmentalism. What if we truly embrace the idea that we’re past the point of no return, and that a catastrophic crisis is just around the corner. That there is nothing we can do to avert a coming environmental apocalypse. If we then give up trying to actually make a difference; our activism is likely still caught up in a deferred desire for a positive outcome. Here we misconstrue the role of fantasy as its disappearance in fulfillment. If however we still give ourselves unconditionally and absolutely to the cause, then it is possible that we are directly assuming our excessive desire for the cause as an end in itself.

Not only is this type of relation to our fantasy healthier, but the type of uncompromising action that comes from this stance is precisely what marks a true militant for truth.

Fulfill Your Dreams… So You Can See How Powerless They Are

In a previous post I contrasted neurotic, psychotic and perverse political strategies to a psychoanalytic approach that attempts to help people realize their fantasy in reality (rather than in a retreat from, or protest against, it). The problem here, as Todd McGowan points out, is that the political potential of psychoanalysis can start to sound like a sophisticated form of the motivational poster that asks us to fulfill our dreams. This however fundamentally misses the truly subversive politicial potential of the discourse.

In order to gain a better understanding of the relationship between fantasy and reality in psychoanalysis (which is a large subject) we should first consider how the realization of the fundamental fantasy in an individual’s social reality is actually traumatic to the subject rather than joyous.

The reason for this stems from the idea that our basic fantasy is a type of lie we tell ourselves in order to cover over the trauma of an originary loss. To directly realize ones fantasy (rather than simply achieving some practical goals) means confronting the deception of the fantasy and thus feel the tremor of an inner lack it covers over. This can be described as a type of failure that is hard baked into the very heart of success.

The success of achieving ones fantasy is ultimately a failure insofar as one perceives their desire as connected to the object that the fantasy aims at. For instance, if one directly fantasizes about becoming a millionaire, then achieving the goal exposes, at a subjective level, how the true function of the fantasy is precisely to keep one from achieving its aim, so that one can keep the fantasy alive. The goal posts must thus be changed by the individual in order to keep the fantasy (and the function of the fantasy) alive. If this doesn’t happen the individual can suffer from a breakdown.

In psychoanalytic theory one of the reasons for confronting our fundamental fantasy is not so that we can better “achieve our goals,” and find fulfillment, but precisely so that we can confront the lie of our fantasy.

The point is not to do away with fantasy, but to try and change the relationship we take up in relation to it. The new relation is one that doesn’t locate the pleasure of the fantasy in achieving it, but in directly assuming the fantasy regardless of fulfilling it. The individual realizes that the goal of fantasy is not in its being swallowed up in some final victory, but is concerned with keeping our desire alive.

Politically speaking, this means that we engage in a certain cause without deferring our pleasure to the point when the cause is achieved. This approach does not simply drain the pleasure out of fighting for the cause in the moment, but it also ensures that any ultimate success is experienced as a type of subjective failure or destitution.

Instead, we must try to reposition ourselves so that we can directly enjoy our commitment to the cause itself; learning to directly embrace it as an end in itself. To do this means that we give ourselves to it in a mode of action outside the realm of economic exchange. From the position of rational calculation this can seem like a form of madness, for if we embrace our cause as an end in itself we might end up giving ourselves to seemingly lost causes.

This is one of the lessons we might take away from the Norse gods. From what I’ve been told (I’ll need to do some research to check), some clans would follow Norse gods destined to defeat. If this is in fact the case, then it gives a powerful expression of the approach outlined here. Namely, that we pursue our highest goal regardless of the ultimate cost or outcome for the pleasure is found in the commitment itself.

Take the example of environmentalism. What if we truly embrace the idea that we’re past the point of no return, and that a catastrophic crisis is just around the corner. That there is nothing we can do to avert a coming environmental apocalypse. If we then give up trying to actually make a difference; our activism is likely still caught up in a deferred desire for a positive outcome. Here we misconstrue the role of fantasy as its disappearance in fulfillment. If however we still give ourselves unconditionally and absolutely to the cause, then it is possible that we are directly assuming our excessive desire for the cause as an end in itself.

Not only is this type of relation to our fantasy healthier, but the type of uncompromising action that comes from this stance is precisely what marks a true militant for truth.

May 6, 2015

Smarting With Pain: On Moral Intention in Harris and Chomsky

This morning I woke up to see that a private exchange had been published between Sam Harris and Noam Chomsky on the issue of moral intention. The exchange is a very interesting and telling one that will no doubt result in many thoughtful and thoughtless responses. In this post I simply wanted to reflect on two questions,

Did Chomsky adequately address the issue of moral intention

Was Chomsky’s anger and frustration warranted

With regards to the first question, Harris makes a very typical move for analytic philosophy and sets up a thought experiment. For brevity I will construct one that operates with the same basic logic,

Person A deliberately kills a child for fun

Person B indirectly kills a child while attempting some moral act

Which person is more morally guilty?

There are other nuances that we won’t consider here (for example person B could be subdivided into one who knew the child would die and one who didn’t, and the nature of the moral act is significant). For the main point that Harris is trying to make can be clearly seen here: that two horrific events are not necessarily to be weighed as morally equivalent. Person A is more morally guilty than person B.

In response to this, Chomsky notes that the thought experiment is either ludicrous or irrelevant. It is ludicrous if Harris is attempting to claim that it is analogous to the situation being debated (9/11 and the bombing of the Al-Shifa pharmaceuticals plant in Sudan). While it is irrelevant if it is simply a mental exercise abstracted from the real world.

Harris clarifies that he is not offering a direct analogy with the event under discussion, so is Chomsky right that this type of thought experiment is thus irrelevant?

The problem is that the thought experiment initially sounds eminently reasonable. Why then does Chomsky view the whole thing as utterly unreasonable? Well, in some strange sci-fi world where a creature’s motives are utterly transparent to itself and/or others, this thought experiment might have some use value. The problem is that the thought experiment is utterly naïve concerning human subjects (for it does not take into consideration the decentering reality of the unconscious).

How many times, for instance, have we acted in a way that we feel fully justified in for rational reasons, only to later feel that we might have been fooling ourselves and actually engaging in some form of rationalisation (the act of constructing reasons to justify our capricious act). For Chomsky, the thought experiment is ultimately irrelevent because it ignores two interconnected realties,

It is very hard to know whether someone is trying to fool us when they give justifications for their actions (being transparent to us)

It is very hard to know if they are fooling themselves (being transparent to themselves)

As Chomsky points out, the majority of people justify the most distasteful acts via reference to moral courage, purity, desire. Even the most monstrous dictators justify their murders with visions of a better world for all, or in claims that that they are picking the least bad path. Are they being honest with us? Are they being honest with themselves? Are they acting with integrity, but within a system that is ultimately destructive? Without a “smoking gun” (say a recording of some politician laughing about how she killed people for sport) how do we begin work through these issues?

What we must do when looking at some injustice is consider the evidence and not get too caught up in intentionality. For instance, if someone is caught speeding, they cannot defend themselves by saying that they did not see the signs. This might well be the case, but it is almost impossible to know. Someone might even think they didn’t see the signs when really they just didn’t pay attention.

The point is that the legal system doesn’t have some accurate lie detector to work out whether a person is deceiving the officer or themselves. As long as there are adequate signposts, the person has done a driving test etc. it has to be judged “objectively,” i.e. without reference to subjective criteria. Any judge would find it an annoying waste of time for a driver to mount a case for their moral superiority over those who know that they are speeding and do it anyway. The judge might say, “yes, feel morally superior if you want. You still have to pay the fine.”

When we take this into consideration we start to see that this eminently reasonable thought-experiment is actually the kind of abstraction people discuss over a dinner table to seem smart. An abstraction that doesn’t take into consideration the unconscious and thus isn’t actually connected to human subjects (with the possible exception of psychotics, who don’t exhibit an unconscious in the way neurotics do).

While Harris wants to maintain that this question has some real-world value, Chomsky wants to point out that it just obfuscates in the name of clarity and plays into the hands of oppressors who have the means to claim moral motives though PR etc. The winning ideological system will generally be better at convincing people that their murders were more ethically justified than others. History is written by the winners after all.

Briefly then, is Chomsky’s frustration and anger justified? Where we fall on that question might lie in what we think of as civil or productive dialogue. But putting that aside, his frustration seems understandable when one sees how, for Chomsky, such discussions (if taken seriously) eclipse the importance of crying out against very real political horrors. Consider this much more grounded “thought experiment” retold by Anthony DeMello in The Song of the Bird,

A dervish was sitting peacefully by a river when a passer-by saw the bore bock of his neck and yielded to the temptation to give it a resounding whack. He was full of wonder at the sound his hand had made on the fleshy neck, but the dervish, smarting with pain, got up to hit him back.

“Wait a minute,” said the aggressor. “You can hit me if you wish. But answer this question first: Was the sound of the whack produced by my hand or by the back of your neck?”

Said the dervish, “Answer that yourself. My pain won’t allow me to theorize. You can afford to do so, because you don’t feel what I feel.”

Not that Harris has attacked Chomsky in this exchange, but for Chomsky these armchair thought experiments are not simply artificial, naïve, and irrelevant. What’s more, they are not just tools to be used by the powerful. They are also too detached from the real world of suffering that exists. Perhaps, as one of my lectures once told me, there will be a day when we can sit around and ask such questions, but today they tend to take our attention away from the cause.

May 2, 2015

The Benefits of Being Odd

When I was home in Belfast recently a friend asked how I remained so immersed in networks made up of people who broadly believe very different things than I do. In asking this question she was referring to both my social circles and working relations in the US. While I had to admit that this situation wasn’t one I actively choose, it had turned out to be deeply enriching.

Back in Northern Ireland I’m much more closely aligned with the political and social outlook of my friends, partly because we have shared a similar journey and influenced each other over the years. But in America I found myself thrown into a very different political and religious environment.

This has turned out to be a great experience, not least because it challenges my tendency to draw lines of solidarity in relation to shared belief. Something that likely reflects a natural tendency in individuals to seek out those who hold broadly the same religious, political and social outlook as themselves.

When nestled in such enclosures our views are largely reinforced and reflected back to us in various ways. What’s more, we can be tempted to take a rose-colored view of these enclosures, while adopting a more cynical view of those occupying different intellectual territories. We can find ourselves inclined to attribute good motives to the former and more insidious motives to the latter.

Being immersed in friendship circles where my theoretical outlook is broadly at odds with my friends and colleagues has acted as a type of short-circuit to those tendencies in my life. I’ve been confronted time and again with gracious, courageous and authentic individuals whose views are ones I disagree with, or even find problematic. It’s also shown me the nasty ways that some intellectuals operating within my theoretical camp have treated these friends. In addition to this it’s given me an opportunity to view some of my beliefs from another person’s perspective, an uncanny experience that can expose the peculiarity of my own cultural position.

I’m not sure how possible it is to choose to immerse ourselves in communities with radically different beliefs and practices to our own. I know individuals who’ve directly attempted this, and the results have generally been poor (the move has seemed heavy handed, patronizing or just plain naïve). Perhaps it is most successful when you don’t directly choose to do it, but rather make other choices that indirectly result in it.

All this to say that my time in America has reminded me that there are revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries within various political and religious/nonreligious camps and that, instead of just building communities of shared belief, we should spend time building solidarity with revolutionary forces wherever we find them.

May 1, 2015

It Spooks: Living in Response to an Unheard Call

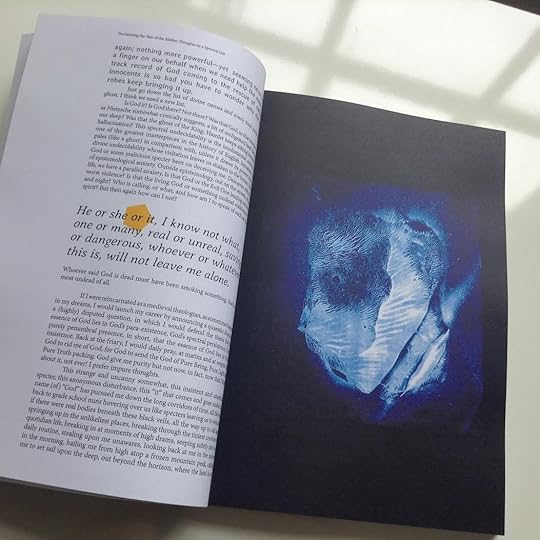

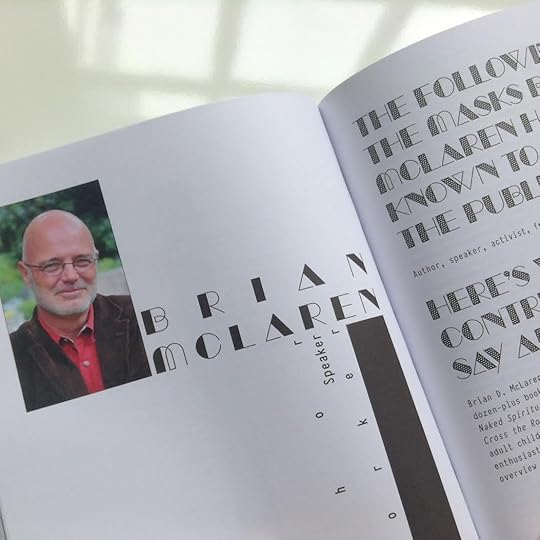

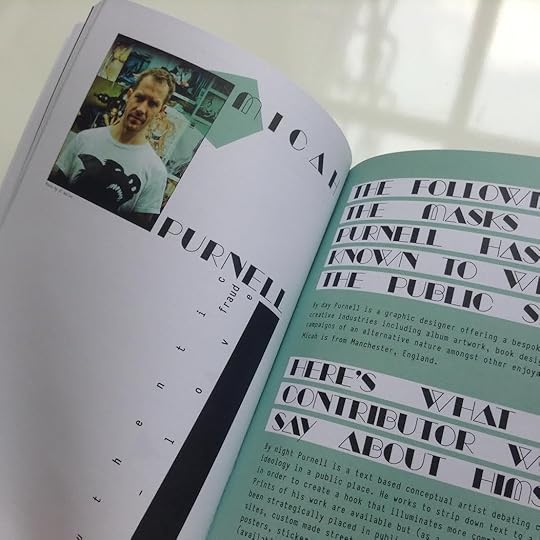

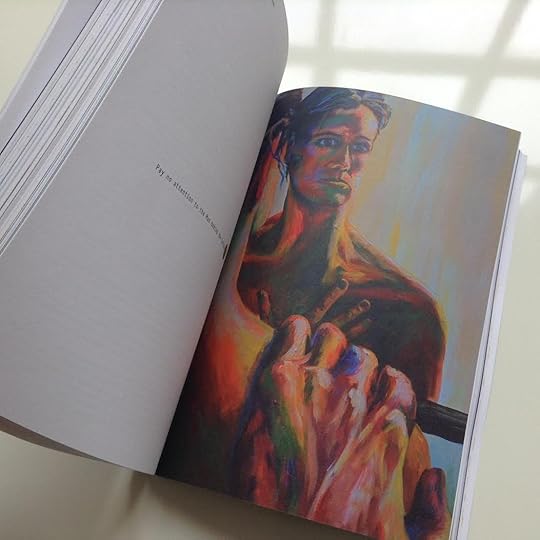

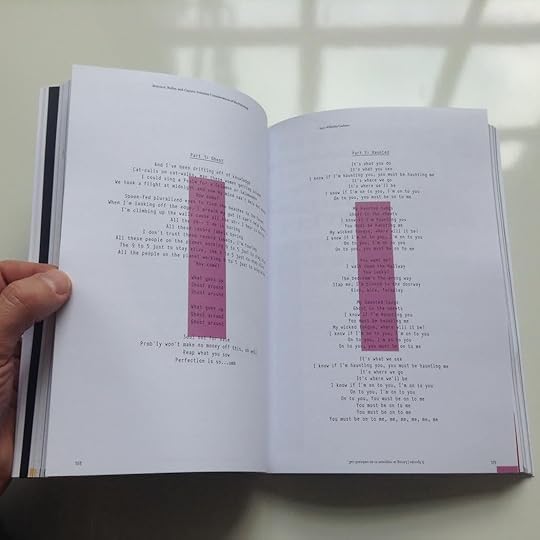

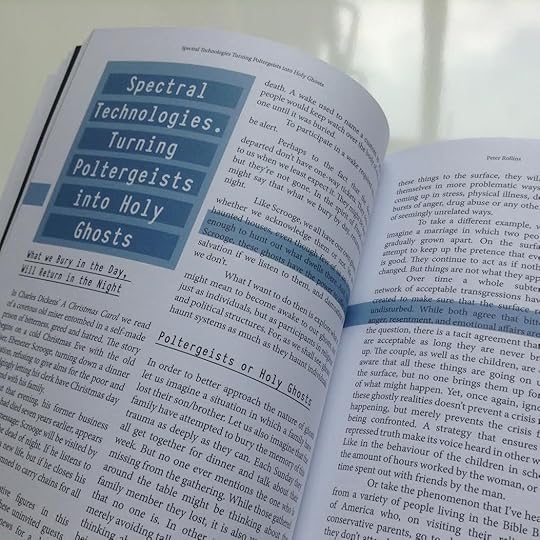

Just over a year ago I sat with my friend Erin in a little coffee shop in Belfast during my April festival. As we talked over coffee she shared her dream of creating a book on Radical Theology. Not just any old book, a book that would bring together a rich array of academics, activists and artists. Her vision was for a work with multiple voices, a work that inspired the reader as much as it informed them. One year later we where back in Belfast celebrating its lanch in the crypt of St. Anne’s Cathdral.

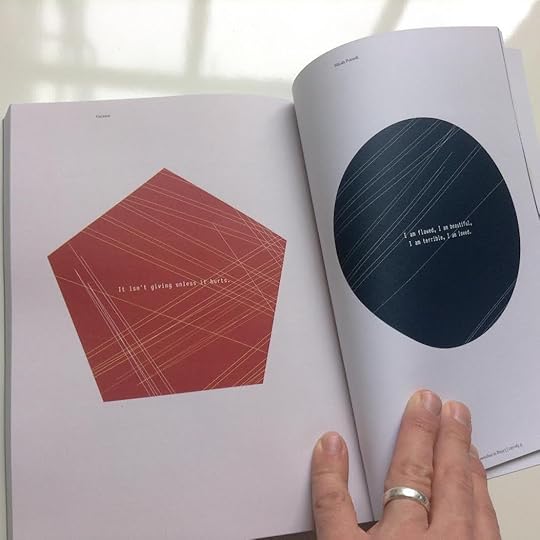

The book begins with a phenominal essay by John Caputo, while the remainder of the book offers various intellectual, biographical, painterly and abstract responses.

I’m so happy that I could have been a part of this project. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen a book quite like it.

You can check out some of the images below. Click here to buy the monochrome version, or here for the full color special edition.

Thank God I’m not like them: On Shaming People’s Defenses as a Defense

Public shaming is as old as humanity itself. At any given time certain behavior is deemed disgusting and worthy of ridicule. Woman have been publicly shamed for having children out of wedlock, men have been ostracized for being gay, and certain sexual practices have been mocked. Shaming that is invariably carried out by those who self-identify as defenders of morality, truth, love and the good.

One contemporary version of this involves ridiculing people due to their perceived psychological defenses. As an example of this I recently came across a religious apologist attacking people who might be called narcissists.

Narcissism seems particularly easy to hate because it appears to describe an individual who thinks they are better than everyone else. An individual seduced by their own image. But just as it’s obvious that someone being gay or straight doesn’t in any way make them moral or immoral, so having narcissistic defenses has no moral dimension. It is simply an unconscious response that an individual employs at certain times in their life. If morality enters in to the discussion, it comes in to play regarding the position we take toward our defenses.

Apart from anything else, shaming someone for being a narcissist means falling for the lie of narcissism. It’s a complicated issue, but often the truth of narcissism is found in the opposite of what it presents us with. It is often a guise that covers over a deep self-shame and self-hatred. What appears as self-love reflects a tragic sense of self-loathing. This is why people who suffer from narcissism often seek help (because they perceive that it is a thin veil that covers over a deep pain).

We all have defenses. Some of us tend to engage in splitting (placing all inner aggression onto another so as to retain our sense of moral purity), others employ denial (repetitively disavowing ones own struggle), while many engage in regression (retreating into childhood interests) or displacement (directing anger at a person who acts as an unconscious stand-in for the real source of our anger).

There are many defenses and getting to know which ones we enlist under stress can be beneficial. In addition to this, the more we confront our defenses the more grace we’ll have towards others.

A good question for us to ask concerns what position we take toward our defenses… Are we aware of them? Do we try to work out what causes them? Do we find ways of giving them positive outlets?

For depending upon how we relate to our defenses they can become a source of great joy and creativity. Someone prone to paranoia, for example, might make a great fiction writer.

Shaming people for their defenses (which is often an expression of the defence that is splitting) can be very damaging as it either encourages the very defense it attacks, or can throw the person into depression by ripping away their defense when what is needed is a therapeutic environment where they can work through what sustains it.

In addition to this, it’s actually really hard to perceive a person’s psychological defenses. Just because someone might appear to us as narcissistic or paranoid, this might not be a pervasive struggle in their life. It’s tempting to reduce people to some kind of easily discernable symptom. So tempting in fact that psychoanalysts are trained not to do it. The idea that complex subjects with rich histories can be reduced to some simple diagnosis is not only reductionist, but detrimental to the therapeutic work. Therapists generally only engage in such activity as a necessary evil (for example, for the sake of insurance companies).

While psychoanalysis has a substantive and evolving theoretical framework designed to guide the therapeutic work, this framework was made for individuals, not individuals for the framework. In simple terms, this means that although the framework can help guide the work of analysis, what happens within the clinic is allowed to feed back upon the framework itself.

In short, categorizing people via their symptoms is a reductionist and violent act that allows for dehumanization and lack of empathy. It allows us to distance ourselves from others, and to temporarily avoid those parts of ourselves that we fear. All of us have defenses, and the game of “thank god I’m not like them” is evidence of one of them.

Some recommended reading,

Why Do I Do That by Joseph Burgo

April 30, 2015

The Secret Philosophical Society, Venice, LA

Nietzsche once proclaimed that God was dead….

…But he also noted that the shadow of this dead god remained fixed on the wall of secular culture. Unlike people who celebrated the decline of church life, he claimed that the most vocal despisers of religion were actually still far too religious. Does this seem familiar?

So you think you’re done with religion? Are you sure religion is done with you?

Our inaugural event we’ll be taking a look the God Machine and the various ways it continues to function in our individual and communal lives.

The evening will be facilitated by myself and cultural theorist Barry Taylor.

The first meeting will take place in the Venice area. Precise location and password will be emailed directly to all members 2 hours prior to the commencement of the event.

Instructions concerning how to join the Society will be posted shortly.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers