Peter Rollins's Blog, page 19

March 24, 2015

Zero Squared Interview

http://peterrollins.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/zerosquare9.mp3

In this interview with Zero Books I talk about my new book, The Divine Magician. The interview proved to be a little controversial. You can read about the subsequent fallout here.

Christ and the Vanishing Act of God

Here I talk about the three parts of a magic trick and how it relates to our understanding of Christianity

The Vanishing Act of God

http://peterrollins.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Peter-Rollins.mp3

This is a talk I gave at Peoria with Imago Dei. Here I talk about Christianity, magic and the freedom from our pursuit of pleasure.

Threshold Sesson 3

This is the third session I taught at Collective in Florida

Threshold Session 2

This is the second session that I taught at Collective in Florida

Threshold Session 1

This is the first session from my Collective event in Florida

Threshold Weekend Kickoff

This is the introduction to a weekend I did in Florida with the Collective community

You’d Better Give Me What I’ve Never Had: Some Thoughts on Nostalgia, Paranoia and Ontic Shock

Nostalgia and paranoia describe two different strategies for avoiding a confrontation with a fundamental loss. In nostalgia, the individual fantasies that there was some previous time in which things were fulfilling and satisfying. Whether the individual idealizes childhood, a previous relationship, or a supposed Golden Era in history the general structure involves imagining a type of lost Eden. It is fueled by the sense that something substantial, something that provided an ultimate plenitude and enjoyment, has disappeared in the sands of time. While conservative political and religious groups rely on this notion of a lost Eden, it is also present in the political and religious left.

Nostalgia is one of the strategies individuals and groups use to avoid confronting the idea that what they feel they have lost never really existed in the first place. This non-existent object that we want to regain is, from a psychoanalytic perspective, formed as we become human subjects. Our genesis is inextricably linked to an illusion concerning a lost object, an illusion that has a fundamental effect on our existence (something I have explored in The Idolatry of God).

The fantasy that we are seduced by can be described like this,

An original wholeness

A fall from that wholeness

A possible future in which we recover that wholeness

Yet what undergirds this fantasy is the following,

A sense of loss

A fantasy about an object that we have been separated from

A fantasy about being able to reclaim that lost object

In other words, the Fall comes first and generates that idea that there was a pre-fall state. An idea that causes us to desire a return to that state. The problem with this is that the only enjoyment one can get from the nostalgic position derives from not bringing back what one thinks one has lost. It is a melancholic enjoyment that revels in fantasizing about a past that never existed, a past that can never be brought back.

Things may well have been better at some previous stage in our lives, but nostalgia is fueled by the fantasy of an impossible past, a past where things truly offered fulfillment. If an individual or community is able to actually get back the Golden Era they feel they’ve lost, they are confronted with the fact that it doesn’t give what the imagined. For example, if the conservative is able to impose “traditional” forms of marriage onto society, then they are faced with the disturbing fact that this doesn’t solve the antagonisms related to intimate relationships. They are brought face to face with what Paul Tillich called “ontic shock” (the trauma of confronting our existential position). Thus the nostalgic strategy is always doomed to fail.

Another flawed strategy employed to avoid this ontic shock is that of paranoia. In paranoia the individual or community doesn’t locate the loss of their enjoyment in the past, but in an other. In this way paranoia is often more destructive that nostalgia, for while nostalgia is more internal, the one who is paranoid has an obstacle to blame for their present state of suffering.

Politically speaking, the paranoid structure is marked by those who believe that there is a vast, well-organized conspiracy at work behind some contingent, chaotic set of events. Some kind of illuminati exist, meeting in smoked filled rooms, controlling things and pulling the strings. The basic example of this paranoid strategy is fascism. Here the fantasy of a Jewish conspiracy is operative. Behind all the seemingly diverse monetary and media institutions, a small group of Jews are in control; manipulating world affairs to their advantage. All kinds of diagrams are created to show how diverse things are linked together.

All paranoid structures replicate this basic logic. Again it is a strategy intimately linked with conservatism, but is again prevalent also on the left. For instance many on the left are fueled by the idea that there are a few people in control who are responsible for all sorts of political events and terrorist activities. The terrorist organization SPECTRE in the James Bond franchise plays into this fantasy, offering the viewer a super-organization secretly in control of everything: toppling governments, instating dictators, assassinating politicians and deciding the fate of whole nations.

The paranoid individual is one who can’t help but obsessively blame some other for their suffering. The more that the other is seen to be enjoying their life, the more angry and bitter the paranoid individual becomes. Ultimately they seek to destroy the other, attempting to disrupt their life and evoke their suffering. While also attempting to draw others into the delusion. The unconscious claim is that the other has stolen my enjoyment, that they have robbed me of my pleasure.

In this way they are able to obfuscate the reality of their lack and blame another for their suffering. They are able to avoid their ontic reality by fantasizing about a non-suffering state effectively walled off by the other. The paranoid individual obsessively attacks the object of their hate and attempts to draw them into the fantasy.

The problem again is that the strategy ultimately fails by keeping the individual from facing their symptoms and learning how to accept them. Whether at an individual, political or religious level, neither nostalgia nor paranoia can succeed in covering over our fundamental condition. Instead we must find ways to face it and integrate it. Here is a link to a talk in which I touch on some of these issues.

These thoughts are directly inspired by my reading of Enjoying What We Don’t Have by Todd McGowan. I highly recommend the book if you’d like to explore these ideas in more depth.

March 13, 2015

Redlands Church, Redlands, CA

I’ll be giving a talk at 8:45am in Redlands Church (520 Brookside Avenue, Redlands, CA 92373). Click here for the website.

I’ll be giving a talk called: Giving the Three-Fingers: Truth, Subversion and Freedom in Faith.

While we sometimes conspire with religious authorities, spiritual gurus and secular advocates in an effort to forget our brokenness and cover over our questions, I’ll explore that idea that Christianity, at its most subversive and incendiary, invites us to face those very things as a means of entering into a more vibrant, healthy and liberating form of life.

March 7, 2015

Formative Years

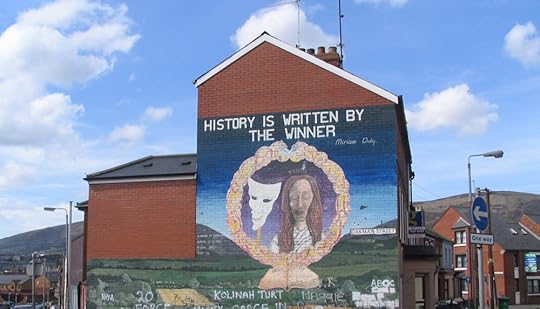

I never met Miriam Daly. She was brutally murdered when I was only seven years old. Indeed, even if her life hadn’t been cut short, the chances of us ever meeting was slim. After all, I was growing up on the other side of the wall that divided our communities. Those responsible for her murder broke into her home on 26th June, kept her captive and waited for the return of her husband so that both could be executed. When they realized that he was in Dublin they shot her before fleeing.

Miriam was a founding member of the Irish Republican Socialist Movement, becoming chairperson after the assassination of Seamus Costello. She was also a prominent activist in the civil rights movement, a key member of the Northern Resistance Movement, part of the Prisoners’ Relatives Action Committee, and sat on the national Hunger Strike Committee,. During this time she was also vocal in opposing Sinn Féin’s move towards federalism.

She was a gifted communicator and academic who could easily have stayed within the safe confines of university life, but who instead became involved in grass-roots politics during some of the darkest and most dangerous days of the conflict. A controversial figure, Miriam spoke out against any talk of peace and reconciliation that implicitly maintained structural injustice. A commitment reiterated by her husband of the 25th anniversary of her death,

“I feel there is at least one thing I can do, and that is to restate an important message she never tired of repeating. It was: to beware of and shun so-called ‘conflict resolution’, the alleged academic discipline which is in fact an imperialist confidence trick.”

I never met Miriam Daly, but I did meet her husband, James Daly. Indeed he became one of the most important and lasting influences in my life. James initially helped show me the importance of theory, and then became my most influential teacher. As a deeply committed Marxist it didn’t matter what course he was teaching. Like salmon returning to their breeding ground, our classes would invariably find their way back to Marxist dialectic. Lectures rarely started on time, and a one hour class would regularly turn into a three hour discussion with blackboards full of esoteric scribblings that took on the aura of scriptural truth for his students.

His passion was, and I am sure still is, intoxicating, and often spilled over in surprising ways. For instance, I remember sitting in a pub with other students one afternoon, listening intently to him discuss Marxism and Scholastic thought in a way that made it feel like the future of the world somehow rested on this subject. In mid sentence a student picked up his phone to answer a call. James instinctively reached out, grabbed the phone and deposited it in the student’s pint without stopping his train of thought.

We all accepted these (not uncommon) events because we knew that we were in the presence of a real thinker. He accepted people from both sides of the political divide. And he didn’t just teach us about justice, he inspired us to enact it. In fact he had a reputation for creating engaged disciples in the university, something I discovered when studying for a Master’s Degree in the Politics department. There I learned that the lecturers had a name for James’ students, those militants who opposed postmodern thought and liberalism at every turn: Dalyites.

At a time when Queens University was transitioning from a place of learning to an industry for the creation of workers, James fought at every turn. He defied every rule and protected the intellectual credibility of the department as best he could. He would tell his most committed students to ignore word limits, write on their passions, and take positions (with the proviso that they wouldn’t tell the department secretary and instead slip the essays under his door while no-one was looking).

One time, when I was sitting perplexed in a huge, austere exam hall, he tapped me on the shoulder and asked if everything was OK. I told him that I was hoping to write on Heidegger, but that there was nothing about him on the paper. He looked at me and said, “you know, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this,” then he glanced up for a moment, took a pen out of his old jacket, and scratched a Heidegger question onto my paper (I didn’t answer it though, fearing that the university would use it against him).

He dedicated himself to teaching and eschewed the university pressure to publish with well known academic houses; choosing instead a tiny publisher run by a former student. He put teaching first, was in constant battle with the analytic department (Queens was one of the few universities that had both an analytic and scholastic department – now it has neither) and was a thorn in the flesh of the academic authorizes – who eventually forced him out.

I never met Miriam Daly, but I encountered some of her spirit in the husband she left behind. A spirit that has provided me with a standard to admire and aspire to. Miriam remains a controversial figure, but regardless of where one stands with regard to her politics, she shows us what commitment to a cause you believe in looks like, and what such a commitment might ultimately cost.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers