Dreaming into the World: Beyond Neurosis, Perversion and Psychosis

One of the critiques often leveled against psychoanalysis is that it is effectively a normalizing discipline. That it aims to integrate the individual back into the social fabric that she feels alienated from.

Politically speaking this is viewed as problematic, for the very experience of psychic alienation testifies to a problematic environment. The truly radical move is not then to reintegrate a community into that system from which their symptom erupts, but rather to help weaponize them so that they might better overcome it. The positions of neurosis, perversion and psychosis are thus romanticized and read as potent outbursts against oppressive systems.

In short, our world is in crisis and the supposedly psychic anomaly of a subjective “disorder” is in fact the Archimedean point to be used for toppling the oppressive system that gave rise to it.

From this perspective the normalizing of the individual or community implies a form of reintegration into a politically, socially or religiously oppressive environment. Instead of birthing a properly dissident political subject, one produces docile and obedient citizens. This critique gains even more persuasive power when one considers how impossible it would be to sustain a therapeutic clinic that seeks to increase dissatisfaction and alienation. The posture of analysis would thus seem to be in opposition to a radically political one.

In light of this there is a tendency for some academics to celebrate the political vitality of neurosis, perversion or psychosis.

Leaning on the insights of Todd McGowan in his excellent Enjoying What we Don’t Have I want to push back on this celebration of such conditions in individual or communal form.

It is true that neurosis, perversion and psychosis are cries against the system that gives rise to them, but the problem in each case lies in the particular way that they remain impotent to change what they cry out against.

In the case of neurosis, the individual or community retreat into fantasy as a means of escaping the exigencies of life. The fantasy provides a way of imagining sexual, political and religious freedom, yet this fantasy doesn’t touch upon the social reality it rejects. It tends to be a retreat from the world as it is, into a purely private world of fantasmic pleasure.

In perversion the individual or community does fight against an oppressive, repressed, and hypocritical system. They don’t retreat into some fantasy life, but attempt to live out their fantasy. Yet the problem here is that the perverse act requires what it fights against, gaining pleasure from provoking the system it rejects. Because of this it becomes a type of transgression that demands what it rejects in order to sustain its libidinal economy.

Finally, in psychosis, one can definitely see an attempt to construct a different type of world that would overcome the one that presently exists. Yet it rarely gains a foothold. In paranoia the individual or community forms a world at radical odds with social reality. It is a world full of dark conspiracies, maniacal villains and insidious plots all aimed at undermining them. Because of the extreme nature of these fantasies it is only in rare moments that they gain any traction at all. The paranoid vision is just too bizarre to make a change and remains on the fringe.

In contrast, psychoanalysis outlines a different approach. It is true that ego psychology can be seen to offer a way of reintegrating people into their social environment, adapting them to their world. However the properly Freudian tradition rejects this. In this tradition the “normal” individual (one who does everything that a given society judges decent, right and upstanding) is considered to be exhibiting a particular type of abnormal reaction.

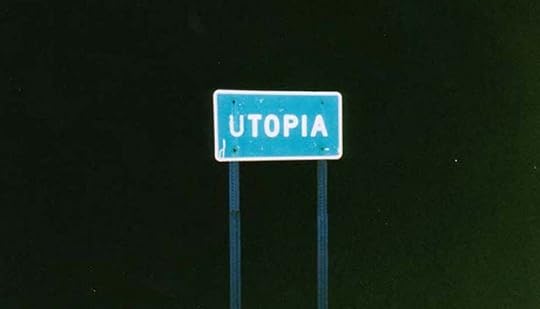

For Freud, the healthy individual was not someone with only a minimal need for fantasy, i.e. someone so content in their world that they don’t require much of a fantasmic supplement. Rather the healthy individual is able to mobilize their fantasies of a better world so that they directly touch upon the social fabric, contributing to its ongoing transformation. Instead of retreating from the world, the healthy individual or community is able to let their dreams impact the world that sustains them and work for real change. Finding satisfaction in this act.

To contrast this with the neurotic act we can say that our fantasy of a better world is not what we use in order to cope with the painful one we inhabit, but rather is the fuel that feeds our desire to make that world less painful.

This is the difference between a hope that we use to avoid changing the world (e.g. the hope that the next world will be better than this one), and a hope that demands our involvement in changing the world (e.g. the hope that there will be justice for minorities brutalized by the State). In other words, a hope that requires my involvement to become a reality. A theme I take up in The Divine Magician.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers