Mary Beard's Blog, page 8

November 23, 2016

Under the wolf and twins!

Yesterday I went to Rome for a one-off gig: to give a speech (lectio magistralis, as it was called appropriately in Latin) on the subject of violence against women. It was in an event held in, and partly organised by, the Camera dei Deputati, the Italian lower house whose Presidente is the excellent Laura Boldrini, sitting next to me in the picture above. It is partly thanks to her, and other women active in the Italian government, that there has been such a lot of public focus in Italy on violence against women. I'm not saying that public focus is the whole solution; but unlike the UK, Italy has ratified the Istanbul Convention (on preventing violence against women) and the event at which I was speaking was the second annual convegno on the subject organised by the Camera dei Deputati and the Council of Europe.

The whole thing took place in the Palazzo Montecitorio, home of the Camera dei Deputati, and rather grander, as these things go than the Palace of Westminster -- though it didnt feel quite as much of a security bunker (there was all the appropriate scanning, but it had a rather lighter public face). And the room in which I gave my talk -- la Sala della Lupa -- was kitted out with a full size replica of the Wolf and Twins.

This was perfect for me. Because my talk was about the cultural inheritance of male violence in something I rather loosely called ( I only had 30 minutes!) the western cultural imagination, and I started with Romulus and the "Rape of the Sabines", which has become so much a title that we tend to forget that it was a pretty brutal act of .. well, rape. (Ancient Roman writers were actually rather better than most of us at remembering quite how awkwardly nasty this foundation story was.) It was fun to do this with baby Romulus just behind, even if only a nineteenth century (?) copy of Bernini's addition to the famous wolf.

I went on from there to later stories from the ancient world (including the Rape of Lucretia and the emperor Nero's kicking of his pregrant wife to death), right up to modern song lyrics (with "pride of place" going to what has become the Welsh rugby anthem, Tom Jones's Delilah -- about a man knifing his ex-partner to death, in case you'd missed it!).

I wasn't advocating banning this kind of stuff. I have no interest whatsoever in trying to create a politically correct version of the Rape of the Sabines (though a few Romans had a go), and censorship of this kind of stuff is never worth the trouble it takes, even if you did think it right (which I don't). What I was trying to argue is that we should be much more prepared to face up to this strand in our cultural inheritance, and not to euphemise rape as abduction or let Nero off the hook, as a lad who went too far after a good night out with the boys.

If you want a flavour of the occasion, there is a mixed English/Italian version of the morning here.

November 19, 2016

Hope Mirrlees and Jane Harrison in "Paris"

Tomorrow, that's Sunday 20th, I have a tiny bit part in a Radio 3 programme, devised by Sandeep Parmar and realised by my friend and excellent BBC impresario Beaty Rubens. Sandeep is one of the BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers (ghastly title, good project), who have been commissioned to make Radio 3 programmes, to get their research out to a wider audience.

I first came across Hope Mirrlees when I was writing my biography (well, sort of "biography") of Newnham classicist (and the first professional woman classicist in the UK) Jane Harrison. Mirrlees was one of Harrison's devoted female pupils at Newnham. She more or less lived with Harrison from 1913, and rivalled another of Harrison's devoted pupils (Jessie Stewart) in writing a biography of their teacher. (That's the pair at the top of ths post.)

Stewart's Jane Ellen Harrison: portrait from letters was published in 1959. Mirrlees' biography was never finished, even though she lived until 1978, half a century after Harrison had died. The notes for Mirrlees' biographical project are in the Newnhan archive . To say say that they are off-puttingly cloying would be an understatement ("Jane was always overcome by the sight of washing hung out to dry" and other such rubbish").

So I recall that I did not have high hopes for the poetry that Mirrlees wrote, with the other string to her bow.

But I was wrong. I remember at the time being very struck by Mirrlees' long poem "Paris", a tribute to the city where she and Harrison lived after their escape from Cambridge. It seemed to my unprofessional eye a bit of an early modernist classic -- with clever plays on the classical and the modern, on Aristophanes Frogs and French "Frogs" (and on the sound of the metro as the sound of the frogs brekekekex koax koax).

And I remember at the time, almost 20 years ago, castigating myself for assuming that this slightly crazy woman (yes.. I still think that... come and read her volumes of notes if you doubt) would not write good poetry. But Sandeep Parmar has done the job properly, so I hope you will will listen at 6.45 tomorrow, Sunday, or on catch up.

November 16, 2016

Emperors in Yale

I have just had an amazing few days in Yale. I have given a big lecture in honour of Michael Rostovtzeff, including going to his grave in the local cemetery (where there was another Scipio Barbatus tomb replica, for those interested).

But of course I had my eyes open for emperors.

That was where my visit to the the Yale Art Gallery and the Yale Center of British Art came in. Both these collections are amazing (and it is eye-opening to see British art from a half external perspective -- that is one of the things that the Yale Centre gives you).

But my eyes were predictably focussing on emperors (and their female counterparts). So it was fun to see the Yale version of Benjamin West's "Agrippina with the Ashes of Germanicus".

and especially G��rome's Colosseum (at the top). I had seen this before, and had realised that the emperors face was modelled after the Grimani Vitellius .

But I hadn't quite realised how curious it all was. For a start, the name of Vitellius is actually inscribed in the painting under his box. But if we are in the Colosseum (which we are -- and indeed this is where the movie Gladiator got its inspiration), then it wasnt built for another 20 years.

So this is another anachronic emperor to go into the book.

November 12, 2016

The pleasure of ruins

When I was first an undergraduate at Newnham (back in 1973), the cool place to live in college was the new "Strachey Building" (evocative pictures here -- some thanks to Debbie Whittaker): it was modern (put up in the lat 1960s), it had student rooms arranged as 'flats', and it had handbasins in every room. I never lived there myself, and indeed when I got a real chance to choose, I had opted for the period Victorian that gave Newnham its distinctive appeal. But in my first year, more than 40 years ago "Strachey" seemed the height of my aspirations.

Now it is being demolished, to make way for a more modern, more fit for purpose, more aesthetically pleasing block.

There are many reasons for this. Mostly, the 1960s building was at the end of its natural life, from the flat roof to the lifts (you can see the problems here). I was among the majority who voted for its demolition. All the same, the ruination of a building that you had once partly inhabited (Strachey housed the college bar, inter alia) is a strange experience. These new ruin images give you a hint of the piquancy of the story. They are as loaded as any 18th century images of ruins are . . . the haunting desolation, the fragmentariness of human habitation, the sites of pleasure literally undermined.

Yet I also can't resist reflecting on a change of culture, and changing expectancies for the life history of a building. Most of my beautiful college is more than a century old. The bit that is being pulled down is the newest. I dont know how long it was expected to last when it was first put up. Was it really only 50 years?

Maybe. But I could wish that we were all building for longer. My Cambridge is still King's College Chapel, standing for centuries. Yet my college is demolishing a building less than 50 years old, and the university is developing a site in West Cambridge that will be time expired before the century is out.

Is it too much to think that in Cambridge we can build the buildings that will be tourist attractions in 500 years time?

OK there are some on the Sidgwick Site, but we need more.

November 9, 2016

Trump: the view from New Haven

I have just come to New Haven to give the Rostovtzeff lecture at Yale, which will be on imperial images, though drawing on different case studies from those I looked at last week. Central on this occasion will be Titian's lost 11 emperors, originally done for the Ducal Palace at Mantua in the 1530s. But more of that later, when I have actually delivered it tomorrow.

For the moment, I'm rather more gripped by the election results. And I confess to having spent the morning in bed watching the television, unedifying as it turns out to be. You can find my first thoughts on this in a "blog-like" post I did for the TLS (It's on a different system, to which I shall soon be migrating. But for the time being I am giving you a link here. Comments as usual on this site.)

Meanwhile as the morning has gone on, the speeches have generally got even less edifying. I realise (as I say in the post I've linked to) that it is generally seen as a good thing that those who were enemies until yesterday are "reaching out" to each other; it's part of the peaceful democratic transmission of power, as the tv commenters keep saying. But the inconsistency with what was being said yesterday is glaring (wasn't Trump saying that he wanted her locked up and would not accept the election result). And the facts are beginning to get less factual. I dont see quite how Paul Ryan gets to the figure of 7 out of 10 Americans wanting to change the direction America is going (Clinton won the popular vote, for heaven's sake).

It was only Clinton and Kaine who avoided the worst of these traps. She was quite straight about accepting the Trump victory, but didn't insincerely praise his virtues. And she went on to reiterate all the things she was fighting for (like women's rights, equality etc), most of which are to say the least not high on the Trump agenda.

Maybe it's paradoxically easier to give a concession speech than a victory speech. But she did it with style.

November 5, 2016

Oxford emperors

I am writing this from Oxford, where I have come to give a couple of lectures (last night the Syme Lecture at Wolfson, and tonight a talk to the undergraduates at St Peter's). The Wolfson occasion was a chance to test-drive some of the ideas I have been working on, as part of my project on modern (ie Renaissance and later) Roman emperors, in front of a partly specialised audience -- some of whom were friends who would not hesitate to say that I was barking up the wrong tree if that is what they thought.

I was talking about various themes of misidentification and its consequences (not unlike, in underlying point, some of what I shall be discussing in Yale next week, but focussing on different case studies -- I'm wanting to try out a variety of my party pieces). And I ended with a particular Oxford story: that is Max Beerbohm's Zuleika Dobson.

The story is a simple one. It tells of the young, exotically named, and stunningly good looking Zuleika who arrives among the dreaming spires to stay with her grandfather, who is the head of the semi-fictional Judas College. Not only does Zuleika herself fall in love for the first time; but all the male undergraduates fall in love with her. Literally all of them: and so badly in love that they end up killing themselves for her, every single one. At the end of the novel the unworldly dons seem hardly to have noticed that the students are all dead (even though the dining hall is strangely empty); meanwhile on the very last page, Zuleika is found making inquiries about how best to get to Cambridge . . . and it���s not too hard to guess what will happen there. It���s a satire not only on the dangers of women, but also on the madness of this masculine university world.

Some of the most engaging characters in the book are the busts of Roman emperors, that stand outside the Sheldonian -- originally placed there in seventeenth century, but thanks to erosion and defacement, they have actually been replaced twice. The current versions are the work of Michael Black in the early 1970s . . .

. . . though examples of some of the earlier series survive: one in the garden of Wadham College, I have just discovered, and one for sale at a local auctioneers a few years ago.

In the novel Beerbohm animates these emperors to make them key observers of the tragic-comic events of the novel. In fact, at the very start they show that they are all too well aware of the trouble in store. For although Zuleika barely gives them a glance as she makes her way to Judas College, the emperors themselves ��� as one old don notices ��� break out into a sweat as they watch her*: ���Great beads of perspiration glistening on their brows���. ���They at least,��� Beerbohm continued, ���foresaw the peril that was overhanging Oxford and they gave such warning as they could. Let that be remembered to their credit. Let that incline us to think more gently of them.���

But there is a twist. For there is no reason whatsoever to suppose that these figures were originally sculpted as emperors at all. Whatever Christopher Wren, as the designer, and his sculptors had in mind in the seventeenth century (perhaps a group of miscellaneous worthies, more likely a line up of ancient boundary markers or ���herms���, which were made in roughly this form), it���s clear that these figures have only much more recently come to be called, and understood as, Roman emperors. In fact, so far as I have been able to discover, Beerbohm���s novel in 1911 is the very first time they get called emperors in print (if anyone knows of something earlier, do let me know).

For me, and the the book I'm writing, it's a great example of the porosity of the artistic category of "Roman emperor" -- here, as elsewhere, images that were never intended as such being appropriated by the Roman imperial "brand".

November 3, 2016

The UL's Cabinet of Curiosities

There is a wonderful exhibition on at the moment at the Cambridge University Library. It's called "Curious Objects" and you can visit in person or online. I may be biased because I gave a little speech at its opening, but I dont think that the unexpected honour (unexpected, because I have not always been the most easy to please of library users, let's put it that way) has clouded my judgement.

Basically, it is selection of some of the many things that have ended up in the UL that are not books (well there were a few books, but not as stars of the show). To put it another way, it was a chance to look back to a time when the University Library was as much a Cabinet of Curiosities as well as a treasure trove of books, and to reflect how, over the last couple of hundred years, disciplinary and institutional boundaries have hardened. Quite a few of the star objecs that you can now see in the Fitzwilliam Museum (such as the famous Eleusis Caryatid brought to Britain by Edward Daniel Clarke) were originally possessions of the Library.

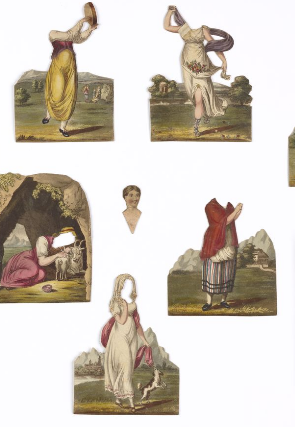

But that description of the underlying history makes the whole show sound much more austere than it is. The objects themselves are fun, and they've been curated with a sense of humour as well as learning. I think my favourite was the eighteenth-century jigsaw above (or technically, as I learnt, a "dissected table" as it wasnt made with a "jig") which illustrated the main characters of Roman history from Romulus to Augustus. I couldn't quite see if there were any women (and rather suspect not), but even so I think that it has some commercial possibilities among the classical fraternity, young and old.

But in the same "toys and games" case, I also took a fancy to the kids' paper cut-outs, with interchangeable heads etc, of Little Henry, Little Fanny and Little Lauretta, all the rage around 1814.

I'm not quite sure if you'd get away with calling a child's game "Little Fanny" any more.

But I got the feeling that for most people I got the feeling that the stars of the show were neither these nor the pieces of Pompeian wallpainting that had somehow found their way back from Italy to Cambridge, nor some of the rather creepy specimens that had been sent to Charles Darwin, nor even the exquisite little eighteenth-century pocket globe. It was the 'ectoplasm' (above), the stuff that is supposed to seep out of a spirit medium during a seance, here in fabric form. It was apparently taken from the medium Helen Duncan, who has otherwise gone down in history as one of the last people to be prosecuted under the 1735 witchcraft act. She had been in touch with a dead sailor during WWII before the official news had been released of his ship having gone down. And it looks as if the only way the authorities could deal with what looked like a security breach was by resurrecting the witchcraft act.

The ectoplasm came to the UL as part of the collection of the Society for Psychical Research. And 'well I never' is about all one cane say.

October 29, 2016

Romulus in Bilbao

On our last day in Asturias, we drove from Oviedo to Bilbao, partly to catch a plane home, and partly to see the Guggenheim Museum there, which we have wanted to do for ages. It was actually a wonderful drive through scenery (sorry Wales) reminiscent of Wales but on a grander scale (this is not at all the conventional image of Spain).

Clich��: the Guggenheim didn't disappoint. The photographs you get of it are amazing.

But they don't quite capture the brilliance of the size, which is both vaster than it looks, and yet somehow avoids ruining everything around it. Another true clich��: when you go in, you feel like you are entering a work of art itself, art displayed displyed within an art object that is always gives you unexpected views of itself and of the outside-- one visual surprise after the next. When you go in, people are always appearing walking along lofty walkways, and half an hour later, you're up there appearing for someone else.

I couldnt help wishing that the new architecture in my own town had a little bit of the bravery thay Frank Gehry gave to Bilbao.

The temporary exhibitions last week were a Francis Bacon show and the last of the School of Paris, 1900-1945. I confess that we gave Bacon a miss. I see why it is important but not sure I want to look at a lot of it. I'm maybe influenced by the husband who remembers from years ago when he was very junior at the ICA, that many rich guys bought Bacons but didn't keep them for very long -- as if somehow you didn't really want to live with them. If I had the money, that might be my view too,

But we did go to the Paris exhibition, which is where I spotted the Alexander Calder version of the Wolf and Twins (1928). I've never known too much about Calder except his mobiles (or 'futiles', as the husband tells me his non-admirers called them). And this was new to me (though a quick Google tells me that it should not have been). But it was a wonderfully down to earth piece, nicely capturing the wiry primitivism of early Rome (I've since learned that the cheap doorstops that served as the wolf's teats captured the popular imagination when it was first exhibited). But all in all a nice antodote to the heroic narrative.

So do go to the Guggenhein, and it's just a short walk away from the Bellas Artes Museum, where you can see, among other thing, a very wonderful/extremely disturbing Cranach Lucretia. That is she above.

This is my last post about Spain.. so a final thank you to all who made it possible.

October 25, 2016

Prize giving

My last two days in Oviedo were for the most part taken up with the celebrations for the Princesa de Asturias awards themselves, largely conducted in the presence of the King and Queen, and on the final day in the presence of what we would call the Queen Mother (that is Queen Sofia, King Felipe's mother). The formal proceedings kicked off with a concert on Thursday night in Oviedo's wonderful concert hall (much more splendid that anything we have in Cambridge -- and the size of the towns must be roughly comparable). It was a performance of Beethoven's Ninth, including the Ode to Joy (as the husband, jokingly observed, this may get banned in Britain before too long... so ENJOY).

Now, I am not a great expert in European (or any other) monarchies, and I suppose if pushed I would be a Republican (to put it another way, I wouldn't have invented monarchy in the first place, but now we have got it, there are quite a lot of other things I would get rid of first!). But the Spanish King and Queen (and Mother) had a rather different style than most of ours (in my limited experience). Sure, there was a lot of security, but there was none of that anxious protocol about how exactly they were to be addressed ("Your Majesty" on first meeting, then "ma'am', said "mam" like "jam", not 'marm'). In fact, once the other side of security, they just mingled, joked and chatted, without obvious minders hovering close; and, more to the point, the king's speech on day two (the award ceremony itself) was a lot meatier, less bland, than most of what you hear from our own lot.

That ceremony took place in the local theatre, to which all us prize winners processed in a motorcade: another first for Beard, as well as the waving at the waiting crowds, of which there were hundreds and hundreds (heaven knows how you judge the sincerity of spontaneity of all this, but it certainly felt 'real').

After walking in on the blue carpet, rather determinedly in my case, we sat on the stage while the citations were read out and we went up to get our scroll and then moved to the front of the stage to wave it triumphantly at the audience, 'victor ludorum' style. In between some of got to make 5 minute speeches. You can see and hear mine here (I hope you enjoy the sentiments about the essential reltionship between history and citizenship, and the sneaking in of John Donne at the end!).

It was actually truly humbling. I was in the great comany of other prize-winners from Nuria Espert to Richard Ford and SOS Children's Villages. And the whole week was all over the Spanish speaking media. It seemed slightly odd in that context that the only mainstream UK reporting that I saw was in the Mail, and an article solely concerned with what Queen Letizia was wearing and whether she was copying Kate Middleton.

Hang on a minute...

October 19, 2016

On cloud nine in Asturias

I am sure it is very bad for one to get treated like royalty, so it is probably a very good thing that in my case it is only going to last a week! Blog regulars may recall that back in May I heard that I had been awarded the Princess of Asturias prize in Social Sciences for 2016. Well here I am in Oviedo to receive the award, and trying damn hard not to let the wonderful reception go to my head -- and really enjoying what I am seeing of, to me, a new part of Spain, and meeting people interested in humanities in all kinds of different ways.

It's a very big occasion in Asturias, and I am being followed round by cameras and interested jounalists -- and am even stopped in the street by people who just want to say congratulations -- and absolutely everything is done for me, from opening the car door to carrying my bag. I guess it's what a few people on the planet have every day, but for me it is a curious and pleasant temporary novelty. This is my view from the stage at the University of Oviedo, where this morning I did a Q and A about Classics and other things. (Thanks all for the tremendous welcome.)

But the visits I have been doing (not just to the university, but including a tour -- part guided by me -- of a vast local Roman villa) have given plenty of more serious food for thought. Much of the discussion, as in the UK, turns to the "crisis in the humanities". What are we to do about cuts to funding? How do we hold our own against the hard sciences etc etc.

It's a serious issue. But my time in Spain has produced as much optimism as pessimism. And that optimism was never more optimistic than on my visit to a local school -- IES Perez de Ayala high school -- where well over 100 kids from 46 schools in the neighbourhood had come to meet me, after spending some months doing all kinds of classical projects. You can see a few of them at the top of this post.

Perez de Ayala is not in a posh area of Oviedo, but is a great hub of Classics (the head is an inspirational classicist, and there are all kinds of traces around the place of that enthusiasm, including memories of their visits to Greece and Italy). And all the pupils who showed up had loads to say about the ancient world, had great questions -- many of which, UK pupils take note, were posed in good English. If this was anything to go by, it didnt seem that the humanities were in terminal decline here.

Nor does it seem in general that public interest in the ancient world was low. The visit to the villa had apparently 'sold' out of the free tickets within an hour or so. And tonight I am doing a night time tour around the local archaeological museum, talking I think to another packed house.

Classics seems so 'cool' here, that one paper called me the Patti Smith of the ancient world. Ms Smith might be horrified at the comparison, but I was jolly touched.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4105 followers