Mary Beard's Blog, page 2

June 23, 2017

How to assess the 'education' in higher education

In all the things we have read about giving Gold, Silver and Bronze ���badges��� this week to universities for their teaching ���excellence��� or not, there has been hardly a mention that this is not the first exercise there has been in assessing university teaching. Almost 20 years ago there was the ���TQA��� (the Teaching Quality Assessment: about which there is rather little on the web but here is a glowing announcement of full marks in the thing from a Cambridge department). It was a huge business: you had to submit boxes and boxes of stuff documenting student feedback, progression, quality assurance etc etc in everything from exams to first year induction programmes, disability provision to staff training. Then there was ���the visit���, where colleagues from other universities came and observed teaching at all levels and talked to students and staff. It will give you an idea of the paperwork that was required when I say that I am still using the pocket folders and box files that once held the thousands upon thousands of words, graphs and statistics that we had to submit.

My Faculty scored the top mark of 24 out of 24. Whether that meant we were excellent at teaching or excellent at preparing submissions of this kind, I really don���t know. Nor do I know whether the enormous number of person hours devoted to the preparation for all this might have been better spent in actually teaching. But whatever, it is quite wrong to imagine that teaching quality at universities has never been examined before the recent ���TEF���.

There are difference between the two. TQA was compulsory; TEF is technically voluntary (but as you can���t increase fees if you don���t enter and get a good score, then in practice it isn���t). And TEF evaluates teaching without actually seeing any teaching at all, but entirely on the basis of ���data��� such as the National Student Survey, employment statistics, and a written submission by the university concerned. This must be a hell of a lot cheaper than the TQA; it is certainly far less disruptive; but one does wonder how far it gives a reliable guide to the quality of the teaching.

I am particularly worried about the Student Survey. This is of course not to say that I am not interested in what students think of the education they are receiving. I cannot imagine any university not wanting to know how their lectures, classes are going down, how students think they might be improved etc. For that matter, I have hardly ever met any university teacher in my whole career who was not interested in the teaching function of a university. They might not all have been equally good at it, but they have never been sniffy about it . . . whatever stories some students of all generations love to tell (there is a big difference between not caring and not seeming to care).

The problem is that this vast tick box questionnaire has been elevated to a dominating role in the whole evaluation, when it should rightly be only one element. And its immediacy is both its virtue and its disadvantage. One way of thinking about the success of teaching is to find a way of judging its instant effects. But I am more interested in thinking about how effective teaching is in the long term, when students reflect 10 or 20 years later on where, how and from whom they best learnt. It is a cliche, but true nonetheless, to say that often you find students, when you meet them a few years on, saying that they really got most out of those teachers who pushed them most, made their heads hurt with new ideas, stretched them beyond the ���comfort zone��� ��� even though they didn���t ���like��� it much at the time.

And feedback is a problem too. These questionnaires assume very standardised view of what ���feedback��� on a piece of written work ��� and it���s rather like the A level version (what assessment objectives have I met? how might I improve this work in order to achieve a higher mark? etc). Of course there is a place for that. But appropriate feedback comes in many forms. I can guarantee that tearing up an inadequate essay in front of the student would get a very bad mark in these survey. And, sure, there would be some occasions when that would be a cruel derogation of duty. But there might be times when it was exactly what���s required. Imagine the very smart student, who is generally winging it (partly because she is putting all her quality time into rowing/acting/you name it). She submits a scrappy couple of pages, with no evidence of any reading at all, that looks as if it has been dashed out in an hour or so. The appropriate feedback there is to get it across that she is wasting both your and her time. And the tear up might be the most effective way of making her see.

Anyway, in reading the Cambridge University submission (brilliantly written with all its frightful jargon), I did discover something I didn���t know already: that over the course of a year 69% of Cambridge students have borrowed a book from a library. Now I know that some subjects aren���t book oriented, and I realise that most of us are reading most journal articles online, and we may well be reading for pleasure electronically too. But are there really 30% of Cambridge students who over a whole year have not borrowed a single book from a library. Heaven help us.

June 17, 2017

A sandy city to visit: Sabbioneta

I went to Mantua for all the obvious ���Roman emperor��� reasons (Mantegna���s ���Camera Picta��� and so forth), but the real eye-opener was the small town of Sabbioneta, about 35 km from Mantua.

This was a perfectly new planned town, launched and designed by Vespasiano Gonzaga (one of a ���cadet branch��� of the Gonzaga family, and in the picture above) in the second half of the sixteenth century. Nothing much has been built there since, apart from a Mussolini school and post-office. But it has none of the tweeness of, say, Pienza (where I spent a few dull hours a few years ago). Sabbioneta feels nicely lived in and not much visited (we hardly met anyone who might be called a tourist); and you can still see what Vespasiano was trying to do.

One sign of this ���unspoiledness��� is the fact that Vespasiano���s Palazzo Ducale is now the HQ of the commune, looking out over the central square. But the highlights for anyone must be, first of all, the restored theatre: one of the first (even the first) internal classical theatres in Europe.

Stunning. But then there was the Palazzo del Giardino, slightly away from the small town centre. I had enormous fun in the ���Camerino dei Cesari��� (first six of the 12 Caesars as numismatic roundels, the second six full length ��� clearly looking back to Titian���s famous eleven at Mantua). Here���s the numismatic Tiberius.

And the amazing long gallery was really amazing (and once more lusciously loaded than this).

But the real message I took away was how many amazing and instructive and important places there are, in Italy and elsewhere, outside the usual ���visitor beat���.

If you get a chance to stop by Sabbonieta (named because it was terribly prone to sand from the river), do���

June 13, 2017

Et tu, Boris

Over the past few days, I have been more interested in the voices of the penumbra of power, rather than in the fate of Mrs May herself. We have been treated to a ringside seat of the the way the second rank ���re-adjust��� to the changing power structures or the virtual assassination of their leader.

I mean we have been looking at a load of Tory ministers, who only last week were toeing the party line and lauding their manifesto as a forward looking plan for the future and a strong and stable Brexit, rushing to tear the whole thing up ��� and telling Theresa May that she must change the leadership style they had only recently been praising.

It doesn���t make you think better of them. If they felt like this before, why didn���t they make a fuss? If they couldn���t stand up to a PM and a couple of Chiefs of Staff, then what hope have they got to stand up to anyone around the Brexit negotiating table? To put that another way, if they were responsible Tory citizens, why didn���t they use their combined muscle against the prime-ministerial style they claim to have hated months ago?

Much more likely, of course, is that they were all paid up supporters of Mrs May, until the going got rough; and that they are now rats leaving the sinking ship, pretending that they had never liked the captains navigation anyway. In which case, they are hypocrites, but hypocrites with a certain pedigree,

Anyone who has studied the ���re-positioning��� that took place among courtiers after the assassination of any Roman emperor, will recognise what is going on. Quick as a flash the lackeys, who had been the old emperor���s right hand men, were claiming that they hadn���t liked him anyway/they had only collaborated to stop things getting worse/that he was a perverted, blinkered madman who deserved everything he got. That is, of course, why the posthumous reputation of any assassinated emperor is so bad: all his previous supporters ganged up after his death to make it look as if they had thought he was a monster all along (but for various reasons had had to keep quiet). Anything to readjust to the new regime.

Don���t trust them, Mrs May. But if I were you, I wouldn���t trust those who claimed to be loyalists either. Another thing that Roman history suggests is that the best way to run a coup is to pretend to be loyal for as long as you possibly can and only break cover at the last minute. Julius Caesar, remember, was assassinated by those who claimed to be his friends. Et tu, Boris?

June 11, 2017

Mantegna in Mantua

I confess that I escaped for election day (fearing the worst). I voted by post and went off to Italy where I had arranged to see some more of the key things I want to discuss in my ���emperors��� book���. You will, I warn you, be hearing about a few more of these (as it was a most amazing three days). But let me start with one of the added extras, one of the surprises that these visits often bring.

I am for obvious reasons quite interested in Mantegna���s Triumphs of Caesar, and in their later reception. And, although it wasn���t exactly top of my shopping list this time, I was aware that there was a (probably) early seventeenth-century set of copies on display in the Palazzo di San Sebastiano. They had been discovered, as frescoes, when a large house in the town was demolished in 1926, and were detached from their wall, restored and remounted in 1936.

Their history is in itself interesting (it is not really clearly who did them, or why), but for me it was a great case of how a copy can make you see the original differently. Here I was struck for various reasons by the copy of Mantegna���s first canvas, seen here in full.

It is the beginning of the triumphal procession and you see the musicians and the men carrying the placards (as they did in a ���real��� triumphal procession) with images of the Roman victorious campaign. It was these placards that first struck me.

I had never before seen quite how nasty the images on them were (look for example at the three corpses hanging on the gallows at the bottom right). My first instinct was that the copyist had been rather over-egging things, and adding some gruesome bits to the original. But when I went back to check it was clear that, although they weren���t so prominent, those gallows were really there.

But the other puzzle was the guy supporting one of the placards at the front of the painting.

In Mantegna���s original, this man is black.

In fact, he was the cause of some controversy in the early twentieth century because when Roger Fry made his bungled attempt to restore the Mantegna originals, by then in Hampton Court, he decided to erase the black face and turn it into a white one (it has subsequently been turned back). What was striking to me, looking at these copies in Mantua, was that the man did not appear black here either. Now, it is possible that the colours have faded (his dark armour, as at Hampton Court) does not appear very dark either). But there is absolutely no sign that the man���s legs are of any different colour from those of the rest of the soldiers.

Did the seventeenth-century copyist also eradicate the one black man in the whole sequence. Or (and this is my hunch) did those restorers in the 1930s (not a time in Italy when racial diversity was being celebrated) take exactly the same line as Fry for whatever reason. One suspects the reason, in both cases, was one that we would not feel very comfortable with now.

Whichever, it is a nice example of the power of the copy.

June 5, 2017

Election 17: rhetoric, argument, half-truths & lies

There is a strange phoney war feel to the last days of the election campaign. All the news is telling us that we are gearing up to the big day, but getting on for 20% of us have already voted in the privacy of our own homes. I suppose it would still be possible to rush round to the Returning Officer and ask to change your mind, but it is hardly a very likely turn of events. So, if not phoney war, it is an odd limbo-like period of reflection.

There are I think some things we have all learnt over the last few weeks, some things to deplore and other bits of largely (but not entirely) gloomy analysis of how politics has been fought out in public. Here are a few semi-connected thoughts. Apologies to be drawing on the Tory campaign (I don���t think the other parties are innocent of some of these faults, mutatis mutandis, but I guess I have been observing May and co more carefully).

I think that the Tories must have learnt at least half a lesson about the dangers of slogans as a replacement for argument, and how they always risk coming round the back to bite you. ���Strong and stable��� looked quite a plausible line, until the debacle of social care turned it into ���weak and wobbly��� and someone came out with the dreadful ���magic money tree��� as the replacement mantra (not much better: most of us thought that they were talking about quantitative easing, or for that matter Boris���s ��350 million NHS bus. (You do wonder who thinks these catchphrases up, and why on earth they dont think better of it the next morning.)

The May autocracy rather imploded too, I am happy to say. I had heard far too much of the first person singular from T. May (���my manifesto��� and so on). The result was that when any other of the senior team were let out, they were alarmingly liable to put their feet in it (Fallon implying a commitment to not raising taxation, Johnson claiming wrongly (let���s hope not dishonestly) that the ��350 million pound pledge was in the manifesto. Right hand clearly didn���t know what left hand was doing, and a really bad advert for what their Brexit negotiating skills might be. (To add to those particular worries, it seemed impossible to get any straight talking out of any of them as to what ���no deal��� might look like ��� which made it in turn impossible to know if ���no deal��� would as Mrs May intoned be better than a ���bad deal���. God help us either way.)

The thing that I hope might just get exploded before the final polling day is the attack on Corbyn, ���the terrorist��� (as against the firm, strong and. let���s not forget, police-cutting hands of the Tory leadership). This is dangerously silly. Of one fact I am absolutely clear: there is no British politician prominent in any of the main parties who wants to see innocent people slaughtered on the streets of Britain, neither Corbyn, May, Farron, Sturgeon, Wood, Lucas or Nuttall, or any that I know. What they disagree about is how to stop that happening. And of course they do, because none of us really knows (I am still waiting to hear what ���deradicalisation��� amounts to.. beyond a rather woolly idea that we can get people who are going down the path of terrorism to very sweetly change their minds). What is clear is that Mrs May and many of the Tory front bench have over the past 15 years shared many of Corbyn���s doubts about the efficacy of the methods proposed (Mrs May, for example voted against ID cards and control orders). I suspect they were all right to have doubts, and I rather respect them for showing it. But when they now pretend that there is a clear division between the Tory party (tough on terror) and the Labour party (weak or collusive with it), I want to take to the streets. And I feel much the same when I hear the stuff about Corbyn sharing platforms with men from Sinn Fein. Let���s not forget that Donald Trump was in the 1990s in a very similar position, indeed at a fundraiser for the nationalists, according to the Irish press. However ghastly he may be, I do not actually think that Trump wants to see innocent people blown up on our streets (even if he is, inadvertently, making that more likely). But if we are going to drag up old photos, then lets drag up them all, including Mr Fallon with Mr Assad (and conversely Mrs Thatcher denouncing Mr Mandela as a terrorist). And better still, lets remember that who we talk to isn���t necessarily who we agree with.

The bottom line is that democratic elections aren���t just about what you argue, but also how; and there the Tories have done democracy a disservice. Sorry for the pomposity, but there you go.

June 3, 2017

Modern elections and the Romans

Classicists (and especially those of us that work on the Roman world) usually have a few party pieces ready prepared for election times. These tend to be of the ���did you know?��� variety.

���Did you know that the word for election candidate comes from Latin candidatus and it means whitened? That���s because those standing for election at Rome used to wear specially whitened togas.

Did you know that a Handbook to Electioneering survives from the Roman world (Commentariolum Petitionis as its standard Latin title has it), full of advice about how to conduct an election campaign? It is actually ascribed to Marcus Cicero���s younger brother Quintus, and purports to be his advice to Marcus for securing his election to the consulship of 63 BCE, but it is rather more likely to be a rhetorical exercise of the first century CE (but no less enlightening for that). It is horribly familiar in all kinds of ways, such as the advice to get out shaking hands and to make sure always to remember people���s names. When I discussed this on the radio with Boris Johnson a few elections back, I remember he was most taken with the bit about how it was OK to promise the electorate what you knew you could not deliver (that���s the ���mark of a good candidate���). That said something, I suspect, about Boris as much as the Romans.

What we more rarely get down to is the ancient process of voting itself, where Republican Rome is again more revealing than anything you find in classical Greece. In both Athens and Sparta, the male citizen body was relatively small (in Athens, fewer than 40,000 and many of those certainly not showing up regularly; perhaps a quarter as many in Sparta). In Athens they all came together and voted by a show of hands, in Sparta they did it by shouting (loudest won ��� which the Athenians thought very weird).

The Romans faced the issue of privacy in the ballot box much more directly than even the Athenians (who had a form of secret ballot for legal cases, but not elsewhere, despite their democratic credentials). In the second half of the second century BC the Romans introduced a series of laws to protect the privacy of voters. We know little about these in any detail, but the conservative huffing and puffing of Cicero makes it clear that this was an ideologically loaded, democratic reform, which aimed to stop the elite putting pressure on the votes of the poor. And it was important enough to be paraded on coins, like the one above, which suggests that voters individually picked out their ballot slips (wax on wood, probably) from a basket as they walked across some form of ���bridge���, then wrote the name of their candidate in the wax as the walked and finally dropped it into the ballot box.

I have always thought there were big problems here, such as who produced all these ballot slips and what on earth they did about the illiterate who could not write the name of their candidate. But there is no doubt that something like that process is going on in the coin image. And the issue of privacy is also obviously at stake when at a certain point a little later in the second century BCE they decided to legislate to narrow the bridges, to prevent interested people getting at the voters there.

But curiously they never seem to have managed the problem of the sheer number of Roman citizens, about 200,000 voters in Rome itself by the mid first century BCE, and many more spread throughout Italy. It looks as if the bare bones of a solution might have been there. The Roman citizens had always been divided into groups of voters, who by a series of incredibly complicated and subtly changing systems (guaranteed to defeat the comprehension of modern students while being the delight of nasty examiners) delivered one vote per group. The whole thing was not unlike the way our own British constituencies work: each group of voters delivers one vote and the person who gets the largest number of group votes wins, and the process saves time, and manages a massive electorate, because all the groups of voters vote simultaneously and conveniently in a location near their home. (One disadvantage is that you can easily get a mismatch between the popular vote taken altogether and the group/constituency vote.)

But the Romans never seem to have devised any system of local voting, so everyone who wanted to participate had to come to the city itself (most of them would not usually have done so). And they never seem to have hit on the idea of the groups voting simultaneously. Instead each group voted sequentially, one after the other, so that it could take more than a single day to deliver the vote, and an awful lot of hanging around for the average voter.

It could be that Julius Caesar was working on some reform of this. And by the time of his assassination he had started some brand new voting halls (saepta, or ���sheep-pens��� as they were called) in the city, to give the voting process a new home. The irony was, of course, that Caesar���s dictatorship was really the end of free democratic elections anyway ��� and within 50 years the saepta had been converted into an upmarket shopping mall, and antiques market.

So pity the poor Roman voter hanging around for hours and hours, and possibly having to come back the next day, when you trot off to the local polling station (or sit down at the kitchen table to fill in your postal ballot).

June 1, 2017

Commencement at Bard

I have to confess that my visit to Shropshire was a bit curtailed by going to Commencement at Bard College, where I was getting an honorary degree. I had never been to a US Commencement before, and I suspect Bard is not typical (it���s what we call in the UK ���Graduation���).

It was a wonderfully sylvan occasion. Just look at the lunch plus Greek temple in the background. To die for, eh? How lucky am I?

But what was really memorable about it was the radical, liberal tradition of US culture and politics being celebrated.

The main speaker on the occasion was John Lewis, the Democrat congressman and ally of Martin Luther King, and rightly an American hero (I walked in the procession behind him, and very rightly BEHIND him, as you can see in the pic at the top of the post). He gave a wonderful address urging the graduating students to be troublemakers, ���necessary troublemakers���. And we all cheered and cheered.

But the whole occasion was affirming ��� for example when we literally cheered again the people who had started their Bard degrees in ���correctional facilities���. And the President, the conductor Leon Botstein, emphasised the radical roots of Bard, in talking about the dark days of modern America, and offering a wonderful, appropriately radical, new version of the Sermon on the Mount (all the better, and the more moving, coming from a secular Jew).

So I was hugely honoured to be there, and to reconnect with my friends in the Classics department. I am not sure how great I look in the academic robes, though.

But good fun and moving in many ways!

May 28, 2017

Roots

The end of last week, I went back to my ���roots��� and made a trip (driven by the son, for which ��� many thanks) to Shropshire. First stop on Thursday night was Cleobury Mortimer, where I spoke about Romans in Britain in the local church (a familiar place from way back as my Dad used to be the architect, by which I don���t mean he designed it, but ���looked after it���). We had great fun, or at least I did (there���s something always a bit exciting looking down a nave). And I think we made quite a bit of cash on ticket sales for the local ���St Mary���s Youth Project���.

Then it was overnighting in Much Wenlock, in the now agreeably poshed-up pub which had been one of my father���s drinking holes, the Raven. It was, I have to say, almost unrecognisable,apart I think for the car park, where I spent many a lonely hour waiting in the car with a coke and crisps, while he propped up the bar (the kind of child-minding which we took for granted then, but I strongly suspect doesn���t happen much any longer, without a knock on the door from Social Services).

I was born in Wenlock Hospital and lived there between the ages of about 5 and 12, in other words through much of the 60s ��� but to be honest I didn���t get much of a chance to become reacquainted with the town, apart from a quick drive round in the morning. Most of it seemed, like the Raven, to have moved a bit up-market, or at least residential. The bakery we had got the bread from is now a rather smart house, and the Police Station is now called the ���Old Police Station��� and is a similarly desirable residence. The one big exception to this is my own old house (it���s what I am walking past in the picture at the top of this post). I hope I am not doing an injustice to the current residents of ���Rose Cottage��� (it wasn���t called that when we lived in it: just plain ���25 Shineton St���), but it actually all looked quite a lot more run down than I remember it.

The reason we didn���t linger in Wenlock, was that we were making for Church Preen School, where my Mum had been head and where I had attended as an infant.

It wasn���t like this when I was there. In fact, my Mum presided over the move in the early 1960s from the ���old school��� (a stunning bit of Norman Shaw architecture) plus an overspill for the juniors in the Village Hall, to the new purpose built building you see in the picture. (We had actually originally lived in the School House until we moved to Wenlock, and it was really nice of the current owners to let me come and explore my old bedroom, still perfectly recognisable: it���s the first floor bedroom with the multi-lit window).

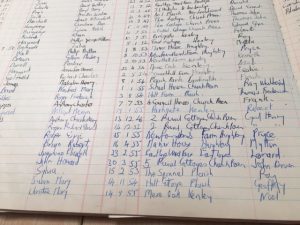

In short, I had a welcome to die for. The head, Dave Tinker, had got out some special memorabilia ��� like the old school register of pupils with ���my��� entry in it, and those of many of my old friends.

And there was also one of my mother���s old log books, recording the rhythms of schools past (the visit of the School Nurse to ���inspect heads���, the outbreak of impetigo, the arrival of the piano tuner, and misdeeds of the boys from Wenlock Secondary Modern, using their water pistols in the playground while they waited for the School bus). Overall, it was striking just from the rather clipped entries, just how much the 11 plus dominated (the exams, the successes, the failures��� ).

Anyway, after this nostalgia fest, I talked to one of the classes for an hour or so. It was partly about life, and how things have changed (or not), about university, about making tv programmes, but also about the Romans as they had been working this term on Pompeii. They read me some great poems they had written on the destruction of the Roman town, and we talked about all kinds of puzzles and questions. One question was about how many people had died there (they had noticed that different books gave different numbers) and this got onto how you might work out how many people had lived there in the first place.

It struck me as we got into this discussion that, even though these kids were only juniors, we were talking about the same basic issues as I talk about with my undergraduates! Smart pupils and well taught I concluded. My Mum would have been proud of them.

May 24, 2017

Happy birthday, DCMS

It is the 25th anniversary of the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport. There is a tendency in my neck of the woods to moan a bit about DCMS, and at times I have been a bit of a moaner, I am sure. But the truth is that everything I have had to do directly with DCMS has been a pleasure (most recently working a little on the commemoration of World War I ��� and I shall ever be proud of my very very small part in the commemoration at St Symphorien in 2014).

It was great fun to go the Department���s away day yesterday and to be allowed to sound off for 30 minutes. It was of course a sad day and in some ways difficult to get into the birthday mood. But I think we all balanced mourning with celebration in a way that felt fine (credit to the organisers there).

So what was my sounding off about?

Well, I had read all the party manifestos and I wasn���t going to be party political in front of a load of civil servants who are bound not to be, but I had been struck by the general feebleness of all their statements on culture (some more feeble than others, let me say). The most depressing thing was the brevity and then the instrumentality of it all. Culture is useful, and even a bargain for the state, because it helps to spread British values overseas/ encourages inward investment/ equals soft power. All that might be true (and I���ve used arguments like that too). But I was trying to put another point.

That is to say, one important reason for sponsoring poetry is because poetry is a good and essential and necessary part of culture in itself, not just because it is a means to an end. And what Roman state patronage of culture suggests (no lessons here) is that we maybe should be backing the cultural awkward squad as well as those who toe the party line; and maybe state sponsored culture doesn���t mean ���boring��� as we are often taught to imagine.

Heaven knows what the first Roman emperor Augustus thought he was getting when he bank-rolled Virgil���s Aeneid. But the result was radically new, disruptive and difficult, and it was a challenge to, as well as an affirmation of, ���Roman values��� (just think of the end, when Aeneas kills his enemy Turnus after he has surrendered���no moral problems there?). And it was partly because of that ���awkwardness��� that the Aeneid has become the most read book ever in the West, after the bible (and with a longer history). Has there ever been a day since 19BCE when someone somewhere has not been reading the Aeneid?

I doubt it. But it was thanks to radical, imaginative, risk friendly and non-instrumental Augustan state sponsorship that we have this poem���

So a warm happy birthday to DCMS, and many more.

May 21, 2017

James Clackson's inaugural: dangerous lunatics?

On Friday, I went to James Clackson���s inaugural lecture as Professor of Classical Philology in Cambridge ��� which turned out to be a wonderful exploration of the history of the study of comparative philology in the university.

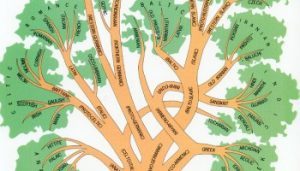

For those of you wondering what comparative philology is, (very roughly) it���s the study of the relationships, similarities and differences in the structure and operation of different languages ��� and, as currently practised in the UK, has a particular strong suit in the study of the Indo-European family of languages ��� those such as Latin, Greek and Sanskrit whose similarities point to a common inheritance from a now lost, ever more ancient language, which is generally called Proto Indo European. (That is cutting corners, but as a working explanation, it will do.)

Anyway, quite a lot of what is now done in comparative philology is what you might call ���technical���, so James���s decision to approach it from the personal and institutional history was spot on for the large, and for the most part ���untechnical���, audience that he got (his title ������Dangerous Lunatics���: Cambridge and Comparative Philology��� helped that). There was lots of fascinating stuff in it, which (as in all the best institutional history) showed you a lot about the intellectual developments of the subject, as well as the sometime curious people involved. But what I shall take away with me is the story of one woman.

As James pointed out, ���philology��� in this sense is now a fairly gender mixed subject ��� with plenty of young women in academic posts across the country. But it certainly didn���t use to be like that. And so, to recognise the invisibility of women (if you see what I mean), he told the story of a woman from Newnham, Eleanor Purdie ��� who had specialised in the subject in the late nineteenth century.

I had heard of Purdie before; in fact we have a Classics prize named after her in college. But, though I have done a bit of work on these nineteenth-century female classicists, to my shame I had rather passed her by. Wrongly, as James showed. She got a First in the Philology option in the Tripos, then went to take a PhD in Freibourg, where she was the first woman to do so (it is said that the fact that women in Cambridge took the degree exams but didn���t actually get degrees made her entry to Freiburg ��� where they predictably wanted certificates ��� a bit tricky). She then held a fellowship at Bryn Mawr, before returning to the UK to teach Classics at Cheltenham Ladies College, where she stayed before retiring early because of ill health.

Her career was a series of the usual exclusions (including being relegated to the acknowledgements of a book that she had actually jointly edited). And apart from one of those ���technical��� philological articles, she published just two elementary Latin textbooks. For those of us are convinced that the simple phrases by which any language is learnt always embody rather more complicated messages than they seem to at first sight, James produced the perfect example from one of those books, Fabulae Heroicae:

���Penelopa femina misera est, sed callida���(���Penelope is an unhappy woman but clever���)

Who he asked was this really about? Isnt it hard to resist the conclusion that in this bit of made-up elementary Latin, Purdie was actually talking about herself. Spot on, I thought and found myself going to take a closer look at Purdie���s Fabulae Heroicae. The rest was not quite as angst-ridden proto-feminist as I had hoped it might be, but it was still well worth scanning for the moral values and rueful personal perspective inscribed.

���Femina pulchra est Penelopa, sed misera quia maritus abest��� (���Penelope is a beautiful woman, but unhappy because her husband is away��� .. Purdie never married)

���Penelopa autem et impigra est semper et impigra esse vult��� (���But Penelope both is always hardworking and wants to be hardworking���.. blimey)

At least it makes a change from Caesar hurrying through the woods.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4103 followers