Mary Beard's Blog, page 6

February 2, 2017

Alternative facts -- about Roman emperors

One of the things that you have to get into the heads of graduate student is the importance of always going back to the original source. You can���t ever trust the reports of others. If you quote an author from a quote in another author, the chances of error are just too high. You���d be amazed how often the quote isn���t actually accurate, or it���s torn misleadingly out of context and the original was actually saying something significantly different from what is claimed.

Anyway today I followed my own advice; and phew! I am in the middle now of my first big chapter in the book and I was wanting a pithy quote to illustrate and enliven my assertion that quite a lot of people have always found the line up of ancient marble bust of emperor in museums a bit dull. It���s one of those things that I remember seeing ever so often in eighteenth and nineteenth century accounts of visiting museums in Italy, but the only reference I had written down was from a book on the Grand Tour (I am not going to say which, on the grounds that only those absolutely certain they are without sin should cast the first stone . . . and we all must have been guilty at some point).

The book referred to a letter by Lady Holland (aka Lady Georgiana Caroline Lennox) complaining about being bored in the Uffizi in 1766 ��� writing frankly, it said, about ���the few very fine things, and the vast deal of tiresome stuff���. After that direct quote, the book went on: ���The tribuna, with its showpieces such as the Venus de Medici, was all very well, she allowed, but there were endless busts of emperors and cabinets of coins and medals to be walked through first. These she had found tedious and boring,���

You can see why I had written it down in my notebook. It looked as if Lady Holland was going to give me just the quote I needed.

But it was just as well I checked in the original text (The Correspondence of Emily Duchess of Leinster, Lady Holland���s sister, published Dublin, 1949), because she said nothing about busts of emperors at all. The direct quote was more or less right (it was actually ���a few very fine things and a vast deal of tiresome stuff���, but I can forgive that). And it may indeed have been busts of emperors that Lady Holland had in mind. But there was actually no mention of them, nor of the Venus de��� Medici, nor of coins and medals ��� despite the phrase ���she allowed���, which implies that she is being quoted in paraphrase. There is in fact nothing at all to explain what she meant by ���tiresome stuff���.

In a way, this doesn���t actually matter very much. But it is a nice example of what happens so often and of how ���alternative facts��� can grow in the academy too. It���s easy enough to think that I might have taken this on trust (it���s a CUP academic book, for heaven���s sake). In fact, I had already planned a sentence running along the lines of ���Lady Holland visiting the Uffizi in 1766 was not the last and probably not the first to find its line-up of Roman emperors. . . ��� And so it would have gained more legs, and in time, requoted, more.

And the other problem is that it���s left me looking for another example. I���ve got something that will do, but not as vivid as I had hoped Lady Holland was going to be. So if anyone has any references that might help me out, do let me know.

(And here is the new version: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/alternative-...)

January 29, 2017

Trump (and Cicero) on torture

Mr Trump���s confidence that torture works (and Mr Nuttall���s suggestion that he would be ���OK��� with waterboarding) brings to mind Greco-Roman practice.

Leaving aside the issue of torture as punishment (and the most gruesome ���executions��� in amphitheatres amounted to that), the most striking and disconcerting use of torture in both Athens and Rome was that applied to slaves ��� in particular the apparent insistence that slaves could only give evidence in judicial cases under torture (that is: not that it was allowed to torture them, but that torture was obligatory).

There has been all kind of modern debate on this. Was the rule, if rule it was, really applied consistently? Did it loosen up over time (in Rome the answer to that is both yes and no)? How was it limited (it was not allowed, for example, to torture a slave to death ��� if only because it deprived the owner of his or her property)? What forms of torture were applied? The answer to that, so far as I know, does not include waterboarding. Various forms of ���racking��� seem to have been popular. And indeed, in a way that might awfully appeal to some of today���s supporters of the practice, some of the violence appears to have been privatised or contracted out. There is a Roman inscription from Puteoli that outlines the contractual duties of the torturing company (who doubled as undertakers), including that they should provide their own equipment. (It���s L���Ann��e Epigraphique 1971, 88 if you want to look it up.)

But perhaps more interesting is the fact that many ancient commenters who talk about this, Cicero included, questioned exactly what we question. How reliable is the evidence that you extract in this way? It seems to have widely accepted that it really wasn���t reliable at all. Indeed what must underlie this is not a desire to get to the facts, but to demonstrate physically the power relations within ancient society, and to make absolutely clear under what conditions different people had a right to speak.

Which presumably is what underlies Mr Trump���s enthusiasm for it, in addition to an inability to think things through.

To ignore the ethics of it for a moment, I find the standard pro-torture argument completely fuddled. You find it commonly said that, awful as it might be, if it saves the life of one innocent US/UK citizen, then it is worth it. BUT hang on. If torture, as many of the ancients realised, produces unreliable information (or, just as bad, a mixture of reliable and unreliable information that you cannot tell apart) then it is likely to put the lives of those innocent US/UK citizens at risk, not save them. It sends the authorities scuttling off to pursue the wrong people, while taking their eyes off the ones who are planning something. It directs the limited resources we have (and however much cash you invest, they always will be limited) to the wrong targets.

In the attempts to combat the threat of terrorism, wrong information is deadly.

Photo Larry Downing

The new site: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/trump-cicero...

January 26, 2017

The wrong Alexander Severus -- and a new book.

I have just started actually writing the book based on my Mellon Lectures in 2011 that I have been working on again these last 18 months thanks to the Leverhulme Trust.

The whole thing has come on a bit, and though I think anyone who attended the lectures will still recognise them (I haven���t changed my mind in a big way), I have put the whole thing together rather differently, and have loads more ���stuff���.

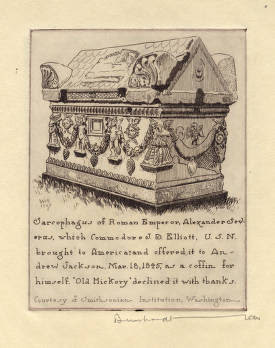

And a good example of that comes at the very beginning (ie the bit I have just written). I start the book in the same place as I started the lectures, with the great sarcophagus that used to stand outside the Arts and Industries building on the Mall in DC. It was brought back from Beirut, one of a pair, in the 1830s by Commodore Jesse Elliott, who had convinced himself that they belonged to the emperor Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea, who were assassinated together in 235.

True, the other coffin did have the name ���Julia Mamaea��� inscribed on it, but it also said that she dies aged 30 (which as one of Elliott���s more sceptical junior officers later pointed out), would have meant she gave birth to Alexander aged 3. Elliott was in fact making one of the classic mistakes in ancient history: to assume that any ���Julia Mamaea��� must have been THE ���Julia Mamaea��� (in fact there were 1000s of them). And anyway, the couple were killed somewhere in northern Europe, and the only ancient tradition on their burial has them buried in Rome not Beirut.

The interest though, as I had fun exploring before, is not so much in the misidentification, but in what Elliott planned to do with ���Alexander������s sarcophagus: namely give it to President Andrew Jackson to reuse as his own. The reason that it ended on the Mall was that Jackson said very firmly that he wasn���t going to be buried in something that had once held an emperor��� his Republican principles were too strong. So it got dumped on the Smithsonian.

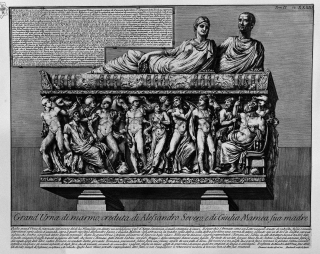

In the book, I have time to briefly explore another side to this story: the fact that at exactly the same time (unknown I am sure to Elliott, or else he was keeping quiet about it), there was a rival candidate for the sarcophagus of Alexander and Mamaea, found just outside Rome in the sixteenth century, drawn by Piranesi and now housed in the Capitoline Museum. This was apparently for shared occupancy, and the images of emperor and mother lie on top.

This is about as fantastic an identification as Elliott���s (and more upmarket nineteenth century guidebooks were already warning their readers not to believe it, even though there has been a recent attempt to revive it in the Journal of Glass Studies for 1990 if you are interested). But it has a UK/British Museum connection. Because another rumour was that the famous Portland Vase was found inside the sarcophagus and had once actually held the ashes of Alexander (and there have been over the years plenty of attempts to tie the design of the vase into a direct connection with Alexander ��� despite the fact that most people think it is about 200 years earlier).

Both are almost certainly mad misidentifications. But one of the things I am trying to do in the book is show how such misidentifications get a life of their own. So I think/hope they make a good start.

*************

And you can go here for the other format.

January 22, 2017

How long, Mr Trump, will you go on abusing our patience?

I did not actually go on an anti-Trump march on Saturday. It���s somewhat to my shame, but not just laziness. I have actually started writing my Images of Emperors book, and at almost 2000 words in I wasn���t going to down tools for even the best cause.

But I am pleased to say that both the children did, the son in DC and the daughter in Rome. I much liked her picture of the march outside the Pantheon (below). But with an even bigger classical theme, thanks very much to @whitmanthesloth for the picture at the top from DC, which uses the first line of Cicero���s In Catilinam I in a very appropriate way (���how long will you go on abusing our patience Catiline/Trump?���)

But as I was musing over the Latin and the protests I was missing, I did find myself pondering also on the history of the protest march, as an institution. How old is it? Well it isn���t ancient that���s for sure. Romans rioted and attacked their political enemies or those who were starving them of food. They could kick up a terrible fuss. But the only time they walked through the streets of the city with placards was in a triumphal procession or other religious celebrations. And that wasn���t protest.

So when does it start (and I guess I am thinking about the UK, but parallels would be useful if you have them).

I thought first of Peterloo in 1819. People certainly ���marched��� in from outside Manchester, but on that occasion those marches were instrumental. They were how you got to the meeting and the speeches, not an end in itself. On a modern march, the speeches at the end are not really the point (and I have hardly ever stayed for that bit)��� it���s taking over the city en masse that���s the main aim.

Maybe the Jarrow marches are closer. But even there the march was partly about getting to London. So is it really not till the Aldermaston marches in the 50s and 60s that we get the first modern protest march as we know it.

Have I forgotten something dead obvious?

(And while you are at it, you might reflect on another of my origin puzzles: when were the first academic conferences as we know them?)

**********

Here is this post in the other format.

January 19, 2017

The inauguration of the week

While everyone is thinking about Donald Trump���s inauguration in Washington DC, I have been to an inaugural occasion much closer to my heart. That is Greg Woolf���s inaugural lecture as Director of the Institute of Classical Studies in London, and Professor of the University.

Greg and I go back a long way: he was a graduate student in Cambridge when I was a young lecturer (and many glasses of plonk have been consumed between us). And here he was introducing himself, as it were, as the new(ish) Director of what is in effect the coordinating research centre of Classics in the country, and the best specialist classical library (which you will shortly be able to support when they launch their appeal).

There are quite a few conventions about inaugural lectures. You are kind of expected to speak to a wide audience and a specialist clientele; you need to look back at your predecessors (cue powerpoint images of largely elderly gents) and offer a vision for the future; you parade some intellectual meat in your specialist area; and you simultaneously treat the whole thing with a degree of self irony.

On all of this Prof Woolf got it spot on. I disagreed fundamentally on his discussion of the different versions of ���humanity��� (question: how does the very nature of the ancient and modern view of what it is to be human differ? . . . I didn���t see quite the difference that he wanted to posit. But it was a rousing performance (and he made the joke about the different inaugurations).

And after there was a nice celebratory dinner, to which Michael Fallon turned up. Say what you like about Sir Michael, he is a loyal supporter of Classics, and rather less self-advertising that some other political classicists we could name.

And do try to read this blog on its new home:

January 15, 2017

The joys of Russian art

The real Museum highlight of the Russian trip was our morning in the New Tretyakov Gallery, whose relationship to the old Tretyakov not unlike that of Tate Modern to old Tate. That is to say it basically houses 20th century and later art. And you can get there easily by Metro, so enjoying that experience on the way. I liked the figure of a studious intellectual lady at our local stop.

The thing that took us to the Tretyakov in the first place was the display of time-expired Soviet statuary in the garden. And this was indeed good, especially in the snow. But it wasn���t quite as good as what I saw in the equivalent in Sofia a couple of years ago (the Moscow ones were a bit too tended to match that neglected, nostalgic, Sofia feel).

But slightly more of a surprise was the extraordinary paintings and ceramics inside the gallery. My knowledge of twentieth-century Russian/Soviet art is a fairly bog standard one ��� Malevich, Kandinsky and Chagall come to mind, but beyond that things get a bit uncertain.

Well, after we had walked very slowly through about three or four rooms (just a tiny proportion of the whole), I remember turning to the rest of the family and observing that I hadn���t seen a single painting that wasn���t really good. Even, as we moved on through time, those that one might be tempted to smirk at (happy workers in the tractor factory et al), were real top of the range!. (To be honest, I got the feeling that things weren���t quite as great after about 1960, but that might be because I was completely knackered by then.)

The Chagall sequence for the Jewish Chamber Theatre in the early 1920s was one standout moment. They were all together in a single room, and for us the whole thing was as impressive as the Calder room in Washington DC I enthused about a few weeks ago.

But every turn brought a gem, like his group of artists (by Pavel Korin).

Or this mock-up of the 1925 Workers��� Club in the Soviet Pavilion at the Paris Exhibition.

And the ceramics were as great as you would predict, but not just the plates. I was particularly taken with the porcelain chess set, by Natalia Danko, pitting the communists against the capitalists (note how the capitalist pawns are in chains). Sadly the museum shop didn���t seem to have grasped (or were rejecting on good principles) the commercial possibilities of replicas of this kind of thing.

Anyway, if you are ever in Moscow, I��� would make a beeline straight for the new Tretyakov. But, you say, I shan���t be flitting off to Russia anytime soon. Well you are in luck. When we got back, I discovered something I should have known all along: that there is an exhibition about to open at the Royal Academy on Soviet revolutionary art, from 1917 to 1932. So make a beeline for that instead.

January 12, 2017

Gazing on the face of Helen of Troy

I mentioned that I had been away. Well, it was to Moscow ��� for four days in temperatures that went as low as minus 24 celsius on the day we returned (on the basis of which I report that minus 24 doesn���t actually feel much colder than minus 14, except that it manages to penetrate into every tiny cavity, from nostril to tear duct).

I had never been before, even though the husband has worked there quite a lot, and it was quite hard to imagine it in its Soviet days. We stayed very near Red Square (slightly undercut by a vast Christmas market and skating rink in the middle of it), and the area was full of Prada, Burberry, Jimmy Choo and other such upmarket bits of retail. It looked to me like a very quick transition had taken place from (the downsides of) communism to (the downsides of) post-capitalism,. But to be honest I didn���t explore other areas much.

The idea was to do some of the big ���must-sees��� ��� but only queuing to get in, if queuing was part of the experience. That meant no to the Kremlin, but yes to Lenin���s Tomb (queue about 40 mins). There���s no dawdling inside (you get about 6 mins inside the building for your 40 min wait), so it wasn���t easy to work out the motives that had brought all the other, almost exclusively Russian, visitors. I certainly wasn���t sure where the boundary lay between tourism, patriotism, nationalism, and a nostalgia for the old days.

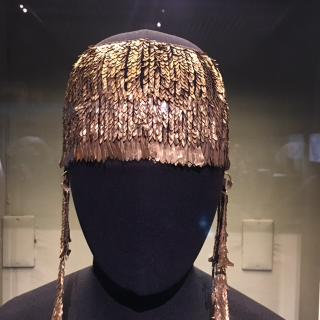

But the high spots were always going to be the museums. On our first day, we went to the Pushkin, via a caf��/bar with a more exotic happy hour than usual. There was a small queue, but no more than 10 minutes . . . we had booked online, but I don���t think it made anything much quicker. The museum itself was tremendous. One obvious reason was that they have on display Schliemann���s gold from Troy, which the Russians took from Berlin in WW2, and have only quite recently admitted they had and put on display (at the top of the post). It���s all the jewellery that you see Mrs Schliemann dressed up in, in the famous photographs, and pretty splendid. I was also pleased to find this more humble Roman terracotta plaque, showing some prisoners in a Roman triumph.

But for me the highlight was a more general one. The Pushkin has one of the world���s best collection of plaster casts of ancient (and other) sculpture. Unlike most big national collections, they haven���t got rid of/out-housed it; nor have they, for the most part, cloistered it off in its own special cast gallery. A good deal of it is spread throughout the museum, rubbing shoulders with ���originals���.

It makes for a striking visual experience, and one you don���t much see here, where collections of plaster copies has been ghettoised since at least the1930s. It���s amazing how quickly you internalise that. I walked into one gallery, where along the wall were several panels of Assyrian reliefs. Funny, I thought, I didn���t realise there were any of those here. And of course there weren���t ���really���. They were casts of the panels in the BM.

And, regulars, please try out the alternative version of this blog to get used to it! Changing soon.

January 8, 2017

A good news story about the NHS

Let me give you a good news story about the NHS, and then ponder a question that it raises.

We had been away for a few days (on which more later) and by the end of the break it was clear that one of the party had a chest infection that, whatever you think of the overuse of antibiotics, was going to need them. But we were back home on Friday too late to get to a GP.

So following the instructions on our GP���s website, we called NHS111 on Saturday morning, got a call back in about 5 minutes from a doctor at the urgent care, out-of-hours service and were given an appointment for 8.30 am (about an hour away). We turned up at the Chesterton Medical Centre about a mile and a half away to find a doctor and a nurse practitioner at work, and just 2 people in the queue in front of us. We were seen at 9.00. (No complaints on the slight delay; the lady in front of us looked quite a lot iller.) By 9.15 we were on our way to the chemist ��� only about 2 hours since we had first rung up. By this time there were 3 others waiting at the Centre.

Ah, you might say, but that���s leafy Cambridge, not the front line. Of course, you are not in crisis, like the rest of us. But NO. As I have often said before, Cambridge is not half as leafy as some sections of the press like to make out. And just a couple of miles away from Chesterton Medical Centre, Addenbrookes��� A and E has been one of the emergency departments with most, and widely reported, difficulties (on the October statistics Cambridge University Hospital Trust was discharging just over 75% of A and E patients within 4 hours, a long way short of its targets). It is possible that, while we were waiting at Chesterton on Saturday morning, Addenbrookes A and E was a haven of peace and speedy turnaround, but I very much doubt it.

So why aren���t people turning up, like us, at the GP���s out of hours service? Well maybe they are and we were just very lucky. But I think there is more to it than that. Part of it may have something to do with the initial encounter with NHS111, which was the only slightly suboptimal element of the whole excellent process. Your call is first answered by someone without apparently very much professional medical training, going through what seems to be a check ���list of questions, some of which are designed to get you to call 999 if its looking really bad. (���Are you confused?��� Don���t say, ���Yes, I am very confused about your questions/the end of the Roman empire/or whatever���, as I guess you will find yourself either cut off or being told to ring 999). That bit of the encounter feels like something of a game of chance, in which you are trying to make clear that you are too ill to be told to take a paracetemol and plenty of fluid, but not ill enough for sirens to be blazing ��� in a way that fits with whatever instructions they have on their screen. It���s not till you actually get to the doctor, that things seem much more personal.

But more to the point, I think, is the NHS111 website and the confusing terminology used on it. As the husband pointed out, if you went to the website on Saturday morning and looked for a medical ���walk-in centre��� in your area, you were likely to be told (as we were) that none were open, except the local major accident department. If we had taken what the site APPEARED to be saying, we might well have fetched up at Addenbrookes. In fact, as no doubt the site said somewhere, but not obviously, we were not really looking for a ���walk-in centre���. We wanted GP out-of-hours emergency care. The Chesterton Medical Centre that we visited was NOT ���walk-in���; you had to ring up and make an appointment But unless you know the terminology, you are going to be misled.

So maybe all these instructions not to go to A and E unless it is absolutely essential, should be rather clearer and more welcoming. I am sure that the NHS admin will say that they have been as clear as they possibly could be. And, strictly speaking, they have been. But it���s all about how NHS111 can ���direct you to the best medical care for you������ which seems a bit vague, and a bit crowded out by other bits of info, like sign language, when to call an ambulance etc. And my own experience says that when you are in a hurry and not very well and anxious about getting treatment pretty soon, you can easily misread and be easily misled.

The basic point is that most of us don���t need emergency care very often for most of our lives. When we do, we want to think someone will be there to make us better. And we are not at our best when it comes to taking things in! Maybe something more like ���If you want to see a doctor now, this is what to do������

January 7, 2017

What's right with UK universities

The proposed reforms of the university system, and the opening up of the right to award degrees to a whole new range of private universities, is about to be given the once over in the House of Lords. But in the run up to that, it has become something of an open season for prejudices about higher education ���informed and ill-informed ��� to be on display all over the media (and, to be fair, some learned support). One particular (and particularly silly) article in the Times, a leader, caught my eye (subscription only, I'm afraid).

My hackles were roused at first because it appeared to equate excellence in UK universities entirely with fields ranging from biochemical research in cancer to neutrinos in physics (so what about history, politics or classics I asked���.?). But it went on to suggest that we, in higher ed., had so reneged on our mission to educate our undergraduates that people like me simply passed on our teaching to graduate students. In other words, the poor sods paying ��9000 were getting a very bad deal (while I put my feet up).

OK, let me confess that I am on research leave at the moment (though I have been replaced by a younger scholar well past her PhD), and let me confess also that for that last 30 years my experience has been mainly Cambridge, with some intervals teaching in Paris and the USA. But from what I know, to suggest that there is a new fashion for illegitimate ���palming off��� of teaching to under-qualified doctoral students is barking mad.

For a start, in Cambridge, doctoral students have been teaching undergraduates in small groups/one-to-one (in supervisions) for all my career there. One of my best teachers ever was the then graduate student (now retired professor of philosophy) who introduced me to the hard edge of Greek philosophy in 1973 (I wasn���t as good a pupil as she was a teacher, I fear). And I think I didn���t do too bad a job in teaching ancient history myself in 1978-9. Doctoral students taking a hand in teaching isn���t a new phenomenon.

And it isn���t a UK phenomenon either. Anyone who goes as an undergraduate to Harvard or most of the famous US universities (liberal arts colleges are different) will find that, while they listen to big lectures by the high profile profs, all their written work will be graded and discussed by the grad students. I have always reckoned, and still do, that we in the UK interact directly with our students more than almost anywhere else in the world.

There is, of course, a professional development aspect here. PhD students are mostly on a career track to an academic job and they need to begin to get experience of teaching and would rightly scream very hard if they were denied the opportunity. Just as those about to enter school teaching have to get experience on pupils before they have actually qualified, so do university teachers (else, cue for the other scream about how we are all hopelessly untrained and think expertise at writing books is good enough for pedagogy too).

That doesn���t mean, contrary to the wilder media reports, that hopeless beginners are let loose entirely unsupervised on the poor young ���consumers���. There are compulsory training courses, lashings of advice from people like me about what to teach and how to go about it (like��� how you get the quiet student to open her or his mouth when the small group has been dominated by a couple of loud mouths). And students are active participants in the process too, not merely passive recipients of drilling. They can make it clear what they want or don���t (sometimes they are wrong, sometimes right). In Cambridge, at least, the best supervisions are when both sides are giving their all to it. And I imagine that is the same everywhere

Inevitably some teaching is better than other teaching. As with most things, it is possible to ensure a degree of competence, not to legislate for brilliance. Some of those doctoral students, closer in age and experience to those they are teaching, will be more inspirational than I am; some of them will be less so.

But what, you ask, do you do about a student teacher who is really hopeless. Let���s take an imaginary case. Suppose there is someone who thinks they would really like to put themselves forward to teach first year undergraduates Greek language, yet I suspect that their own language is not strong enough for that (there is a huge difference between a good passive knowledge and an active teaching capacity). What do I do? I tell them it straight of course. And I explain that I have a duty to all sides in arranging teaching: to the graduate student who wants to get and experience, and to the students who want to learn. I have to be able to look both sides in the eye.

December 30, 2016

How should the humanities make the news?

It is very hard to know how you get humanities research in the headlines. My recent brush with the Henry VIII tapestries is a case in point. I was extremely excited to find a specimen of what I think is one of the later branches of the family tree of Henry���s originals. But the only way that is deemed newsworthy is if it can be trailed as one of Henry���s originals, that once hung in Hampton Court: as a ���discovery��� in other words.

But this is only one instance among many of turning the kind of work I do into ���news��� on the scientific model. To be fair to my scientific colleagues, they probably cringe at the way science is presented on the news (���boffins discover that water is bad for you��� or whatever). But there is something dispiriting in the way that every intellectual step forward, every rethink has to be presented as ���new��� else it wouldn���t get any air time.

I remember a few years back I was giving a lecture at a northern university (with a particularly active press office) on the Philogelos or ���Roman joke book���. They had hyped the lecture in a big way, as new insights (which in some important ways it was). On the train up, journalists kept ringing my mobile. Their first question was: where had I found this text? The right answer was obviously ���I dug it up from the sands of Egypt���. When I said that I found it on the library, they instantly lost interest ��� even though I was doing something with the text that no one (I think) had done before.

What counts as new and newsworthy is the question.

And that is exactly what my own august university struggles with. They have just issued on the website a top 24 of Cambridge research stories this year. On my reckoning, 19 of those are pure science; and, of the rest, the majority are fascinating discovery or rediscovery stories (whether archaeology or a lost musical manuscript). Hang on I think, what are the rest of us doing? Does it really need to be under the radar, compared with (say) the mating call of mice? You���d think from looking at this roster that none of the work that some of us do rethinking Greek tragedy, or the demography of the medieval city, or the impact of T. S. Eliot counted for a hill of beans.

So does it?

To put it another way, if we can���t find a way of explaining (and convincing our universities why it deserves explaining) how those of us who work in humanities have an innovative story to tell, we are lost. Why, for example, do we think we now think differently about the ���fall��� of the Roman Empire from Gibbon? Might that not be a story to tell��� or a story to find a more impressive way to tell?

And there are plenty of other examples we could all add to.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4106 followers