Mary Beard's Blog, page 5

March 9, 2017

Seventh heaven

I am in seventh heaven. I am staying in the American Academy in Rome for a month, with the aim to get a chapter and a half of my new book written (as well as checking out a few images I really need to see first hand).

It may sound glam. But the truth is that I am not actually enjoying the city much, nor am I planning to (though, I confess, I did walk down the hill from the Academy to have a great meal in Trastevere last night). My days so far have been in the library from before 9.00 till after 7.00, and never have days gone faster, with only a quick coffee and lunch break. That's the bar above where I have my morning coffee and late night grappa.

So why be in Rome?

Partly because it puts a barrier between me and the other demands of life. When did I last get a full day in the library absolutely undisturbed? Partly because it is so proximate to some of the stuff I really need to see again at first hand (like the 'room of the emperors' in the Capitoline Museum).

It feels like being a graduate student again (but without all the time wasting habits). It is possible to work quicker and more effectively in this environment than anywhere I else I know. Much the same goes too for the British equivalent (which has close ties with the American Academy, and where I shall be going next week). It may look like an academic holiday camp in a glorious location, and I am privileged to be here. But it gets the work done, and a half.

March 4, 2017

The Old Boys' (and Girls') Magazine

There is something disconcertingly gripping about those glimpses you get of your old friends and enemies, and of their successes, from alumni/ae magazines. They are a bit like round-robin Christmas letters, a bit too full of successes, but -- though we laugh at them -- we read them none the less. It sort of explains the one-time success of Friends United, which I did from time to time consult, with a combination of humility and Schadenfreude.

I have missed out on my school Old Girls magazine, because my best mate and I were the two who put up our hands in that closing meeting in the school library and said that we did NOT want to join the Old Girls��� Association ( a big mistake I now realise). But I do still get my College equivalent.

These little bits of ephemeral literature have changed over the years. My own college���s used to be deeply austere: barely a picture and lists and lists of names, and of births, marriages and deaths, that would have meant nothing to an outsider, or even an insider who wasn���t looking for someone special. They have brightened up a good deal, with chatty articles about the college now, reports from the JCR president, of what happened at the May Ball and how the new building is shaping up. I am pleased to say that Newnham���s version of this genre has successfully resisted that awful ���company report��� look that so many similar versions now ape. It will come as no surprise to the editors that I could do without so many pictures of babies of alumnae (one of my far more illustrious predecessors said that she liked babies, but she liked their mothers more) ��� but it���s a minor fault within the genre.

The odd thing is, of course, that ��� for all the new gloss ��� it���s the obituaries that are still the most gripping thing: that snapshot of lives short and long, ambitions realised and thwarted, and achievement and implied bitterness in almost every sense. This year���s collection ranged from the well-known Lisa Jardine to the obviously extraordinary Stella Ambache (the first female GP in Chislehurst, which I bet was hard work); from born and bred Cambridge girls to those from Sudetenland, New York and Hong Kong (Newnham���s been multicultural for its whole history); from those committed to an unimaginable degree of service (���during the harsh winter months she was know to walk to school and back when public transport was cancelled due to heavy snow carrying her pupils��� homework with her so she could mark their work in the evening. A servant always������) to those who you suspect must have felt that they were born just a bit too early (���Had she lived in a later generation she might have become a barrister���).

But the aggregate of all these dead women���s achievements couldn���t help but make me feel just a little bit proud of my own college (and also, of course, to have that awful fast forward moment to when people would be reading about me).

The new version is here: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/old-boys-gir...

March 2, 2017

Herland

I have now got a text of the lecture about ���Women in Power��� (from antiquity to Mrs May) that I am giving for the London Review of Books in the British Museum tomorrow evening (a nice indication of the very friendly rivalry between the TLS and LRB that I am allowed out to do this!). It is also going to be broadcast in a slightly edited form on Radio 4 on Monday at 8.00. Not too heavily edited I hope, but where occasionally I stop to chat about a slide on the screen, the radio audience will be spared the tantalising puzzle of what on earth I am talking about.

There is something very nerve wracking about doing one of these gigs, especially with a radio tie-in. The basic point is that if you turn up and give merely an OK lecture in front of a few hundred people, there IS a degree of humiliation attached. It���s not nice walking out of the lecture room behind a couple of people, who don���t know you are in hearing distance and are saying ���well, that was alright, but really not her best���. But on the radio it lives with you a lot longer, online, in tweets and emails and whatever. The humiliation for getting it even a bit wrong is far greater.

The truth is that the actual writing doesn���t take hugely long. It���s the way that it invades your head for weeks that is the time-consuming bit. When you are not actually thinking about anything else, like in my case emperors (and my ���imperial��� trip to Dublin is something I shall return to soon), it���s always invading your thoughts and your sleep. How am I going to move from A to B? What exactly am I trying to say? How will I tie things up at the end, and so forth?

In this case, I have to thank the son, who gave me Charlotte Perkins Gilman���s Herland for Christmas ��� a wonderful, and knowing, early twentieth-century fantasy about a long lost nation of women only, invaded by some American blokes. It has given me a beginning and an end, as I hope you will see. And well worth a read it is too.

I hope you will enjoy the lecture too!

The new version: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/herland/

February 26, 2017

Snowflakes

In my long experience (including being a student myself), students protest about many different things. Some of it is irritating, some of it is silly and some of it is absolutely spot on and makes people change their views. If you asked me to define the duties of a student I would certainly include speaking up and protesting about what they see as wrong. That indeed has been the launch pad for all kinds of reforms, from well before 1968. And they have a much clearer view than many of us oldies.

My job, I guess, is to resist with exactly that voice of experience (sorry if that sounds patronising, but there you are). Protests shouldn���t ever be kicking at an open door. I disagree fundamentally with some of the demands, and I will speak up. I don���t want to issue trigger warnings because I am about to discuss the rape of Lucretia (for a start that tends to focus all that I want to say about early Roman history onto that instance of sexual violence . . . it highlights as much as it warns). And I have big problems with no-platforming. I want to hear every (legal) view on the planet and then argue with it, and no-platforming and safe spaces make me shuddering. But student protests have made me look again at what I do and what I think (have I actually talked too flippantly about Roman sexual violence? Have I used the fact that I have been raped as an alibi for doing so?) .

But one thing is for sure, I do not walk around my campus every day anxious about what I might or might not say. Maybe I am blind, but I don���t see a culture of fear in the university of Cambridge, any more than when I was a student and I challenged the norms about women etc. Though, in the newspapers, a culture of fear is exactly what we are told is the norm.

The latest example of this was blazoned in a Sunday paper today (after a report in a local student newspaper). Students at one Cambridge college were said to have been outraged by the colonial implications of ���Jamaican Stew��� and other such multi-cultural menus (which have nothing much to do with their country of origin). Fair enough I think, in a way. But it did rather gloss over the fact that every residential institution argues about its FOOD (this is a different version of the usual, but it comes down to the same thing). And it also glossed over the fact that there were some powerful student statements in gratitude to the catering staff. Not sure that in my day we were as good at recognising the labour of those that put food on our tables.

February 23, 2017

In our Time with Seneca

I was on In our Time this morning, talking with Catharine Edwards and Alessandro Schiesaro about Seneca, Roman philosopher, writer, and courtier (recently one of the main players in Peter Stothard���s book The Senecans ��� and it���s in that context that he was freshest in my mind). You can listen to the full version, plus the extra conversation that happened after the end of the programme here.

In our Time has become an institution over almost 20 years. If you don���t know it, it is a very simple formula: once a week, apart from a short summer break, Melvyn Bragg plus three academics (originally two) discuss some humanities or science topic for 45 minutes (originally 30), live. This week it was Seneca, next week the Kuiper Belt.

The fact that it is live adds to the edginess of it. If you make a major fluff, it can���t be edited out; it���s there for all to hear forever. One thing I always make sure I have up my sleeve some halfway elegant way out of a question I really cant answer (���Mary, could you give us a quick summary of what Seneca is actually arguing in the De Vita Beata?��� ���Well, I think that���s something Alessandro could do a lot more eloquently that me���).

And I do mean that any fluffs are there to hear forever, as the past programmes are all on the programme website. They are great stuff, listened to by thousands and thousands (including, to my knowledge undergraduates, who often kick off and essay, or finish off revision, with a quick listen in to what three illuminate have to say).

It is a bit like doing a radio exam. In some ways that���s like doing QuestionTime: the questions and discussion aren���t quite so open ended (no one���s going to come out with an unexpected challenge on nuclear power), and there is some briefing beforehand about the rough route map of the programme. But on the other hand the subject is something you are supposed to know about (in the end I would be forgiven for not knowing the ins and outs of nuclear power, not so easily for not knowing the ins and outs of the reign of Nero). The potential loss of bella figura is proportionately greater.

In fact it does all take a bit of time. You talk to an excellent person from the programme (in this case Victoria Brignell) about the general topic first, a week or so in advance. Then early in the week of the broadcast, you talk again about the general direction of flow. Meanwhile, there is the revision: in my case I thought I should re-read De Clementia and the Apocolocyntosis, as well as a couple of things my fellow panellists had written on the subject. If you come from out of London, you are very very strongly encouraged to spend the night in a hotel near Broadcasting House, in case you miss the 8.30 start. So I fell asleep last night in the Melia, over the Cambridge Companion to Seneca.

How it came across, you will have to judge for yourselves. But I enjoyed it.

Here's the other version: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/in-our-time-...

February 19, 2017

What price nostalgia?

I have always thought that the one thing that defined Greco Roman thought was a nostalgic (and simultaneously radical) vision of the world. For the ancients, if you wanted to change the way things were done, you went back to the distant past. To put it another way, every Athenian who wanted to push for radical reform in the fifth century BC claimed that he (or she, but the she���s are off the radar) was returning to the reforms of Solon.

The basic principle that I learnt, taught to me by Moses Finley way back, was that ancient radicalism was built on nostalgia. Revolution was always built on the revolutions of the past. Finley always used to say that WE have been brought up on a progressive ideology (we are making things better by pressing forward to the future). But the Greeks saw progress in a return to the past.

It was always a myth. And it raises all those issues that come up with the far right now more than ever. When the followers of Trump claim they are making America great again, when are we actually going back to? Like segregation? Who wants to go back to the US in the 50s and 60s? And when was the British high spot ���?

Can we challenge the new US president to move out of this nostalgiac enclave, and ask where we are going back to and what for.

February 16, 2017

Displacement activity

I have been making steady progress with writing the emperors book, but not quite at the rate I had being hoping. That is to say, I have not often made my target of 1000 words a day. But (as is always the way) as soon I should really be doing something else I start to have a spurt.

That ���something else��� is the lecture I am giving on 3 March at the British Museum (for the LRB) on ���Women in Power���. In some ways it is a sequel to the ���Public Voice of Women��� that I gave in 2014, but it has got to go a good way beyond that and not just repeat, with variants. In that old lecture I explored the way that women in the West, from the Homeric Age on, had quite simply been SHUT UP by men (���Oh do shut up, dear��� was its other title). Now I want to take a closer look at some wider aspects of female power (or powerlessness).

It���s fairly clear to me that ��� whatever individual examples of political leaders etc you can now think of -- there really is no cultural template for powerful women. Look, for example, at the political uniform of the trouser suit, adopted by Angela Merkel and Hillary Clinton (as near to male costume as you could get). And it���s fairly clear too that there is a good deal of misogyny in the public sphere. But that on its own isn���t very interesting (of course there is, you might say). What is much more interesting, and harder to pin down, is what kind of misogyny, with what kind of cultural roots, and with what effects. I���m certainly going to be having a look at the image of Medusa, deployed against Clinton, Merkel and others.

The other issue of course is what we mean by women ���in power���. Most of the discussions out there are about either women in the legislature (a ranking topped by Rwanda with 63%) or about women as CEOs. But is that what we mean by ���power��� with all the superwoman and glass ceiling associations? I don���t think it can be the be all and end all. But how do you redefine���?

Well that���s what I am thinking about. And, in comparison, writing about emperors seems a smoother path.

Here's the link to the otehr version: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/displacement...

February 12, 2017

Good politics and good art?

I have just been to get a glimpse of the new exhibition at the Royal Academy: Revolution, Russian Art 1917-1932. And I went with especial enthusiasm after having had this surprising encounter with twentieth-century Russian art in Moscow after Christmas.

It was, in a word, amazing ��� and unsettling. I went on in that earlier blog about the wonderful ceramics of the earliest Soviet era��� and there were plenty of those. But it was the unsettling side of the RA show that was most memorable.

The final room, after you had enjoyed the stunning paintings etc, from 1917-1932, included a memory room��� an appropriate black box in which you could see the photographs of those who died under (and thanks to) Stalin. That was a good way, I thought, of reminding every visitor to look behind the aesthetics to the murderous politics. (Declare an interest here: I am part of the Academy home team in a way��� but I would be as critical as anyone if I wanted to be.)

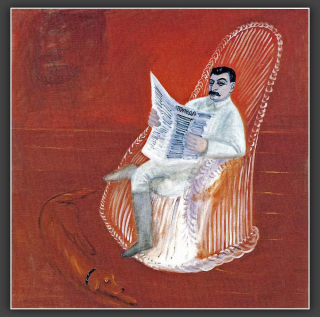

For me though it was some of the art that did that job even more powerfully. One of the most striking images was Rublev���s 1930���s painting of Stalin reading Pravda (at the top), with an apparently contented dog at his feet. Don���t forget, we were being told, that the most vicious dictators can look like this to some people. And we were being asked what difference that sanitisation makes (Whose false consciousness is it? And what false consciousness? Our���s, the artist���s?) .

But there was a sense in some of the responses to the show that, even so, nasty dictatorships are still thought to produce nasty art. If only it were so simple ��� though that does lie behind the view that somehow it was (nice) Greek democracy that produced (nice) Greek art. And that is what some critics indeed said.

I was struck in one paper by the comment: ���The brief but soaring flight of the Russian avant-garde falls to earth in a silt of Stalinist kitsch���. Ok, a genuine aesthetic judgment that may be. But I couldn���t help thinking that it was underpinned by the conviction that Stalinist stuff could only be kitsch. For me, as I hope some of these images shows, there is a lot more to it that that.

And THAT is worth talking about.

The other version: http://www.the-tls.co.uk/good-politic...

February 8, 2017

Augustus, Jesus and the Sibyl: the story so far

Sometimes Twitter is wonderful. I was just writing a couple of sentences of my book a few days ago about what was once a well known story of the emperor Augustus, the image of the Virgin and Child, and the Tiburtine Sibyl (or ���prophetess���). I had tapped down some confident words more or less to this effect: ���this scene was one of the commonest in the early modern period, but is now one of the least recognised���. . .

But then I had a crisis of confidence. Maybe everyone really knew this story, and I was being a complete twat, as well as dangerously patronising to suggest in print that it was largely unknown. (Imagine the ignominy��� nothing annoys a reader more than the author telling them they wont know something they learned on their mother���s knee). So I tweeted��� can the Twittersphere help? Is the story of Augustus, Jesus and the Sibyl now well known?

Sorry if this is going back to emperors, which I promised I wasn���t. But it is with a different twist.

One of the first reactions was from those who kindly pointed out to me that there was actually a system on Twitter for having a quick opinion poll (I had seen this in other people���s tweets, but never known how to do it, now I do.. thanks all). But even my rudimentary attempt at a Twitter poll produced the overwhelming result: NO, this is not a well-known story. And I promised to explain what exactly the story was.

The question underlying my own interest was this: how did people in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period reconcile the story of Jesus with the story of the Roman emperors (Jesus was born in the reign of Augustus after all, and crucified in the reign of Tiberius). What follows is a simplified version of just one version of that out of many. I haven���t yet got back to the, medieval, original sources (I will when I return to a fuller discussion, more than the couple of sentences I have penned for Chap 1, later in the book; the Golden Legend is one, but there are others). Certainly a long history lies behind the images.

To cut a very complicated story short: it was the day of Jesus���s birth and the emperor Augustus serendipitously asked the pagan prophetess, the Sibyl, if there would ever be someone born more powerful than himself; the Sibyl showed him the answer in the sky, where a vision the Virgin and child appeared.

But in more detailed versions of the story there are links to buildings and dedications in Rome: in particular to the church of the Ara Coeli on the Capitol in Rome. One story was that Augustus set up, in response to the vision, an Ara Primogeniti Dei, meaning ���Altar of the Firstborn of God.���. Later this became the nucleus church of the Ara Coeli (the church we still walk past, on the left, on the way up to the Capitol)..

Whatever the precise details, for me what is interesting is the engagement of early modern writers, painters and thinkers, in linking the Christian and the imperial story. And this story, with all the many paintings that engage with and illustrate it, is one of the places where we see this most clearly. And I am hoping that my book will open some of these connections up.

(You have Caron, Ghirlandaio, unknown Venetian and `Veronese above... and here is the new version:

http://www.the-tls.co.uk/augustus-jes...

try it!)

February 5, 2017

The Houghton Emperors

I promise that this will be the last imperial post for a while. But I do want to give you a glimpse of a wonderful little show at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge ��� displaying a pair of splendid busts of Commodus and Septimius Severus that usually stand in the Stone Hall at Houghton Hall in Norfolk, decorated under the eye of Robert Walpole. (You can just see them in the pic above, on either side of Laocoon.)

They actually belong to the Fitzwilliam ��� in the sense that they were accepted by the government in lieu of death duties a few years ago, formally allocated to the Fitz, but in practice left where they had actually been for 300 years alongside other antiquities acquired for Walpole and a variety of eighteenth-century copies and pastiches (including a splendid Rysbrack of Walpole himself in Roman guise). The human equivalent would be to say that the Fitzwilliam has custody, Houghton has care and control.

Anyway, they have come for a brief visit to Cambridge, where it is interesting to see them in a completely different setting ��� and next to a Rysbrack terracotta version of the Walpole portrait bust.

And partly to celebrate that, the museum hosted an evening discussion on Friday ��� a ���conversation��� between Lucilla Burn (recently retired keeper of antiquities there, and the organiser of the show) and me, combined with a viewing of the emperors concerned.

We started off talking about the ancient context of the pieces, and how they were identified at Commodus and Septimius Severus. It���s a huge hornets nest, to be honest ��� all depending on how far you see imperial portraits as the result of a centralized operation, pouring out the official version of the emperor across the empire to subjects who would never see him in the flesh. Some of it must have been centralised (else how do you explain the fact that very similar portraits, right down to the locks of the hair, are found on different sides of the Roman world?); but how much? And if it was, why do we hear absolutely nothing about it in any written evidence at all?

But towards the end, we got onto the eighteenth-century context, and that old favourite topic of how to understand the Roman-style dress in which so many of these busts are apparently clad. I���ve read a lot more about this than I had when I first began to think about it (and I got a huge amount out of Malcolm Baker���s Marble Index, if you are looking for bibliography). But I���m still interested in that transition, some time in the first half of the nineteenth century, when the toga went from seeming a ���natural��� way to present someone, to being more like fancy dress.

More later!

(And here is the version we shall soon be fully migrating to...

http://www.the-tls.co.uk/the-houghton...

...have to say I am quite looking forward to not having to do two versions of each post)

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4104 followers