James Clackson's inaugural: dangerous lunatics?

On Friday, I went to James Clackson���s inaugural lecture as Professor of Classical Philology in Cambridge ��� which turned out to be a wonderful exploration of the history of the study of comparative philology in the university.

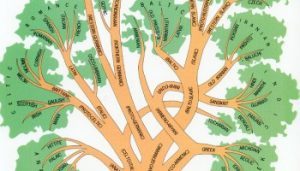

For those of you wondering what comparative philology is, (very roughly) it���s the study of the relationships, similarities and differences in the structure and operation of different languages ��� and, as currently practised in the UK, has a particular strong suit in the study of the Indo-European family of languages ��� those such as Latin, Greek and Sanskrit whose similarities point to a common inheritance from a now lost, ever more ancient language, which is generally called Proto Indo European. (That is cutting corners, but as a working explanation, it will do.)

Anyway, quite a lot of what is now done in comparative philology is what you might call ���technical���, so James���s decision to approach it from the personal and institutional history was spot on for the large, and for the most part ���untechnical���, audience that he got (his title ������Dangerous Lunatics���: Cambridge and Comparative Philology��� helped that). There was lots of fascinating stuff in it, which (as in all the best institutional history) showed you a lot about the intellectual developments of the subject, as well as the sometime curious people involved. But what I shall take away with me is the story of one woman.

As James pointed out, ���philology��� in this sense is now a fairly gender mixed subject ��� with plenty of young women in academic posts across the country. But it certainly didn���t use to be like that. And so, to recognise the invisibility of women (if you see what I mean), he told the story of a woman from Newnham, Eleanor Purdie ��� who had specialised in the subject in the late nineteenth century.

I had heard of Purdie before; in fact we have a Classics prize named after her in college. But, though I have done a bit of work on these nineteenth-century female classicists, to my shame I had rather passed her by. Wrongly, as James showed. She got a First in the Philology option in the Tripos, then went to take a PhD in Freibourg, where she was the first woman to do so (it is said that the fact that women in Cambridge took the degree exams but didn���t actually get degrees made her entry to Freiburg ��� where they predictably wanted certificates ��� a bit tricky). She then held a fellowship at Bryn Mawr, before returning to the UK to teach Classics at Cheltenham Ladies College, where she stayed before retiring early because of ill health.

Her career was a series of the usual exclusions (including being relegated to the acknowledgements of a book that she had actually jointly edited). And apart from one of those ���technical��� philological articles, she published just two elementary Latin textbooks. For those of us are convinced that the simple phrases by which any language is learnt always embody rather more complicated messages than they seem to at first sight, James produced the perfect example from one of those books, Fabulae Heroicae:

���Penelopa femina misera est, sed callida���(���Penelope is an unhappy woman but clever���)

Who he asked was this really about? Isnt it hard to resist the conclusion that in this bit of made-up elementary Latin, Purdie was actually talking about herself. Spot on, I thought and found myself going to take a closer look at Purdie���s Fabulae Heroicae. The rest was not quite as angst-ridden proto-feminist as I had hoped it might be, but it was still well worth scanning for the moral values and rueful personal perspective inscribed.

���Femina pulchra est Penelopa, sed misera quia maritus abest��� (���Penelope is a beautiful woman, but unhappy because her husband is away��� .. Purdie never married)

���Penelopa autem et impigra est semper et impigra esse vult��� (���But Penelope both is always hardworking and wants to be hardworking���.. blimey)

At least it makes a change from Caesar hurrying through the woods.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers