Mary Beard's Blog, page 11

August 11, 2016

What does the Latin actually say?

People often imagine that if you 'know Latin' you can read more or less any bit of the language that is put in front of you (much like what you can do if you 'know French'). It isn't really like that at all. OK, there are some easy bits. A basic tombstone doesn't present much of a problem. After all most epitaphs are pretty formulaic, with a few additional idiosyncratic, personal details. And quite a lot of what you read in Latin, you have read before, at least by my age.

I have often said that more things survive (in both Greek and Latin) of what the ancient Romans wrote than anyone could hope to read in a lifetime. And that's true. But it's also true that you do go back time and time again to some of the same classics: in my case, Cicero, Tacitus and Livy. And there it is not so much a question of reading, as of re-reading -- and it's that what enables you to skip at a reasonably cracking pace.

It's not really the same when you are reading anything complicated for the first time. I dont think students realise this very often, when you are taking them through some particularly tricky bit of (say) Tacitus. "Oh come on," you say with slightly feigned weariness, "you can see where the verb in this sentence is, cant you?" And it is not often that you confess that when you yourself first clapped eyes on this particular passage at their age, you couldn't make head or tail of it either (though I have been confessing that more as I get older).

I still remember an eye-opening moment when some elderly professor of Greek, giving a visiting lecture when I was an undergraduate at Cambridge, boldly stated that the only Greek authors he could read fluently were Homer and Herodotus (and I think he should have added the Greek New Testament -- in each case we know the crib rarher well). I couldn't work out if this was hugely reassuring, or if it meant, more gloomily, that I was committing myself to a life in which I would never quite feel I had mastered the languages I thought I was trying to learn.

Why, I still wonder, are Latin and Greek so hard. I think it is partly that most of us, even if we have done our turn in trying to translate English into Latin, still learn ancient languages largely passively. It is both the plus and the minus of Latin that we never have to ask for a pizza, or the way to the swimming pool, in it. But more to the point is that most of the classics we have to read in Latin, or Greek, are so damn difficult. Making sense of Thucydides or Tacitus is closer to making sense of James Joyce than Charles Dickens . . . and after even 10 years at the language one is hardly quite up to the task (and it was probably almost as baffling for native speakers too).

The truth is that for most of the canonical greats, there are always translations if you get stuck. That isn't so with what I am working on now. I am in the middle of my project on images of Roman emperors in post Renaissance art. And one of the things I am trying to get under my belt are the largely sixteenth-century portrait books, with their series of great men and women from history, pictures plus short biographies -- usually centring on a run of emperors. They are, however, intriguingly different: they choose different characters, they end in different places right up to the (then) present day rulers, and the images bear all kinds of different relationships to surviving images on coins. The image at the top of this post is from the earliest of the lot, the Illustrium Imagines of 1517, and it's the entry for Julius Caesar.

I am by no means the first to work on these, but I am currently trying to think a bit harder about how the 'bad' emperors were understood within the series, and what the books were really for. How did you package, for a sixteenth-century readership, Nero or Caligula. This, of course, means looking hard at what the Latin texts actually say, because most of them are not in the vernacular. Some of them are easy enough when you get into them. The blurb under Caesar, above, says that the bodily and mental qualities of Caesar are very well known, so the author will restrict himself to a brief description of his physical appearance : tall stature, white skin etc...

But most of the stuff -- especially the explanatory prefaces to any of 15 or so books -- is much longer, and more argumentatively tortuous, and to be honest difficult. And you are on your own: there's no crib here, like there is with Tacitus. So 50 years of learning Latin is now being tested at the frontline.

Dispatches will come later.

August 7, 2016

Feedback loop

I am generally getting fed up to be asked to feed back. Almost every time you spend a night in a hotel, you get an email form shortly after asking you to rank various aspects that you weren't very concerned about anyway ('convenience of elevators? please rank on scale of 1 to 10, in which 1 indicates very dissatisfied and 10 indicates very satisfied'); and more often than not they will include a link to Tripadvisor for good measure. Much the same happens when we have taken the car in for a service, had an encounter in the building society, or bought a mobile phone. Sometimes it is even more irrritating than an email; it's a phone call at some particularly inconvenient moment ('I just wanted to ask you a few questions about your experience with . . . yesterday').

Everyone knows this is the score, and in fact the more desperate victims of it actually ask you as you leave the establishment concerned to say nice things about them in the inevitable feedback request (could be counter-productive I'd say). To be honest, I can't imagine that the results are particularly reliable or helpful. Just to take a simple example, I always give my garage ten out of ten, whatever has happened. That's because I have used them for years, want the people who have looked after my car to feel happy -- and if anything has gone wrong, I would have it out face to face with them, not dob them in to Big Brother.

But the irony is that when you do have a complaint that you actually want to make, in a way that doesn't quite fit in with the 'on a scale of 1 to 10' format, they tend to be much less interested.

Now, credit where credit is due . I had a run in with Balfour Beatty recently, whose lighting schemes are currently detracting from the Cambridge cityscape. But the man charged with the public relations role answered promptly, frankly but courteously, and to the point. Likewise (another one for Cambridge folk), if I have ever had a problem with Panther Taxis (hasn't been often), I've always had a full and quick reply, that wasnt just a cover up.

In fact it is the very organisations that are most eager to send you a feedback form which tend to be the worst in answering your spontaneous comments in any constructive way. I am, in general, a loyal customer of British Airways (not perfect, but a hell of a lot better than most of the competition), but they are one of the worst culprits in the bland style of customer relations ('Dear Professor Beard, I am sorry that on this occasion you were disappointed with our usually high quality of service; but we thank you for your custom and look forward to welcoming you on board again soon'). It is possible to break through this ('I wasnt talking about being 'disappointed', I was complaining that my flight was cancelled; could you tell me why...'), but it takes perseverance. The same is true of Abebooks, whom I use a lot, maybe a lot more than I should (they are owned by Amazon, I should remind you). They are not quite so eager as Amazon itself in finding out your view of their packaging, but when I pointed out recently that my order with a seller had been delayed for weeks as they were on holiday, I was basically told I was wrong ('Typically this situation is the result of the book being sold to another customer in the seller's walk-in store or on another website, or the seller may have experienced technical or logistic issues in warehouses or storage centers'), and it took a bit of a fight to prove my point.

So the moral? Well it's a bit like the 'questionnaire fatigue' that some of our students now suffer from (always being asked if the lecture was at the right level, if the power points were up to scratch, and if they could find the books in the library). We long suffering customers have had quite enough forms and tick-boxes -- and many of us would rather that these firms diverted some of the vast amount of money they now spend on mass feedback forms to hiring people who would answer properly, independently, promptly and honestly the queries and complaints we do want to raise, when we want to raise them.

August 4, 2016

Let's send the Olympics back to Greece

I do occasionally get interested in a bit of sport. I watched Murray's Wimbledon final, and got half interested in the fortunes of plucky Leicester, Iceland and Wales on the football field. But the thought of the diet of the Olympic Games on the telly over the next however many weeks fills me with a mixture of horror and nausea.

I can admire the skill and training of someone who can run unbelievably fast or jump unbelievably high, but I dont feel much need to watch them at it. And I have precious little interest in all the scandals that surround the whole show. Particularly the doping. That's partly because the logic of it all seems to me so dodgy. It's a bit like trying to explain to a child why tobacco is legal and cannabis not. I haven't ever really grasped why some odd things you can feed into your body are OK, but others not. Is it about protecting the health of the athletes long term? Though, I assume that quite a lot of what is entirely legal, like wall to wall training, is not going to do the athletes much good in years to come . . . even my own early brushes with trampolining have taken a toll on my knees). Or is it about making sure that the competition is "fair"? In which case, maybe you could let them all take, or do, whatever they wanted in order to win. (Though I suppose I wouldn't want that to apply to other forms of cheating, like tripping or pushing...? But the peleton . . . ?)

And it's not as if things are now much worse than they used to be. The scandals may have changed, but there were always scandals and fights of some sort. Back in the days of Avery Brundage (or Slavery Bondage as he was pointedly nicknamed), the sometimes very violent dispute were all about who counted as an "amateur" ("professionalism" then being as toxic as doping now).

The final straw is what it does to the host nation, I mean the legacy -- or lack of it. I suspect that if was an inhabitant of Rio de Janeiro, I would have been there trying to pour water on the flame (though I also suspect it takes more than water to douse what must be a gas torch).

The obvious answer, if we are going to continue is one that has been suggested before: make a permanent base for them at Olympia itself. It's not as if the ancient Olympics were morally much better than the modern ones, and they were certainly much messier (more like Glastonbury than Rio). But at least they didn't move around.

So why not build a nice sporting centre somewhere near the old site (pictured at the top of this post). It could host conferences and other competitions in the interveing years. And it might even give a boost to the Greek economy. Or, to put it more cruelly, if the Greeks are so proud to have invented them, then they can deal with the consequences of what they created.

July 30, 2016

"Sir" Philip Green... should stay "Sir"

I hold no brief for Sir Philip Green. What I hear about him, I dont like. But I dont know how far he has gone too far, or how different he is from those who don't get found out. At the same time I dont think that the campaign to strip him of his knighthood is quite hitting the right target. I am not sure that honours, if they should be awarded at all, should be awarded provisionally, on condition of good future behaviour.

For a start, there is the randomness of the 'finding out" principle, or the intermittent rule changes. However immoral or unworthy Sir Philip may have been, I bet there are, or have been, quite a few others who have turned out to be just as unworthy but have not been found out. In fact, I seem to remember, Lord Archer only escaped because of the timing of the rule change that made forfeiting an honour a more feasible procedure. But more to the point, are the principles and practices of the honours system, and the due diligence required in making sure that gongs are not given to 'the inappropriate'.

I am sure that there are a lot of big retailers who are as white as the driven snow, but I share the suspicion of many people that the proportion of dodgy 'customers' to be found among the ranks of super successful, self-made )or not self-made), mega-rich entrepreneurs is likely to be a bit larger than in the bulk of the population. To put that another way, you are surely asking for it, if you choose to hand out rewards to massive donors to political parties and their ilk.

One way of dealing with this is the current way of imagining that honours are held 'on licence' .. step out of line, or be painfully revealed as the character you always were, and we'll take it away. A better way is to think harder who you give these things to in the first place. When 'we' (or 'they') get it wrong, then the Sir Philips of this world are there for all to see the errors of judgement. (It is a bit, in my view, like the statue of Cecil Rhodes.. we need to face up to our honouring of him, not pretend we didnt).

Perhaps in cases like this, the people who should really carry the can are not the honorand (who can live with the embarrassment of his gong for ever) but those who, for whatever reason, awarded the damn thing in the first place, for reasons that I suspect dont always bear too much scrutiny.

Who knighted Sir Philip? I thnk it was Tony Blair.

(Declaration of interest, I have a modest OBE.)

July 27, 2016

The pleasures, and kindness, of Trier

I have been to Trier for a couple of days, to see a trio of exhibitions on the Emperor Nero. You will be able to read a review of these in the TLS in a couple of weeks, so I'm not going to preempt that now. But here's a bit of background and tourst info.

Trier is one of the biggest and best Roman towns in the West, with a standing city gate, the 'Porta Nigra' (you can see that in the picture above with the mock soldiers -- a monument preserved, as they so often are, because it was converted into a church). It had its glory days in the late Roman empire, when it became one of the mini capitals outside Rome. We went there to film parts of the last episode of Ultimate Rome -- it was damn cold and snowing (and I was happily introduced to handwarmers!) but still it left a good memory.

So it was with a certain pleasure that I went back in search of Nero (and especially, as it was the theme of one of the three shows, the afterlife of Nero -- close to the subject of my current research project).

I stayed, where we had stayed before, in the Hotel Mercure Porta Nigra (perfectly just across the street from the gate) and did the three Nero shows with rather obsessional intensity. That meant rather less time and attention on the other things worth seeing there (the Rheinisches Landesmuseum has a truly extraordinary collection of Roman provincial art .. and a good excuse for another trip).

But the thing I will remember is quite how nice and friendly everyone was. I had discovered that on my last visit. As we were filming, I put my notebook down on top of a radiator in the Porta Nigra, knowing that it was a colossally stupod place to put it as I would be bound to forget it.. as indeed I did. It wasn't life threatening, but annoying; and I kicked myself...

... until about a week later I got an email from a man who had found it (my email address was on the front page), offering to send it back to the UK, which he indeed he did.

It was a tremendous act of kindness, matched again on this occassion -- when I managed to leave my mobile phone in a cab. I assumed that it was gone for good. But the combination of the hotel receptionist, the museum cloakroom staff (who had booked the cab), and the driver himself produced it in the hotel bar within 30 minutes of me realising I had lost it.

So very good memories. If you want to get there, it's more accessible than you might think -- half an hour's drive from Luxembourg airport across an open Schengen border.

July 22, 2016

Follow my leader

While I am on the subject of slogans ('democracy' in my last post), let me move on to 'leadership'. The husband has long hated this one, and I am beginning to join him. That's partly, I guess, because we have been hearing the word on every news and comment programme as a mantra against Corbyn (whatever it is, Corbyn is repeatedly said not to possess it). But it's not just upper echelon politics, we're constantly being told that we want head teachers, hospital managers, univeristy vice-chancellors, museum directors who are 'leaders'. And there are all kinds of courses available, I'm told, which are solely directed to teaching leadership (and no doubt making money from doing, or claiming to do, exactly that).

Now, obviously, I am all in favour of people in positions of responsibility having the skills to do the job. If heads, or anyone, have to make big financial decisions, then it's a very good idea to have proper training to do that. And there is nothing the matter with a bit of charisma here and there, though too much charisma can be too much of a good thing. My problems are in the implications of this idea of 'leadership' -- ones that don't make it to the news when we are discussing Corbyn, management styles, the success of UK schools, or whatever.

For a start, if some are 'leaders' what does that make the rest of us? 'Followers', presumably. So I find myself asking, what does it take to be a good follower? And when are there going to be courses in that? (Captains of industry.. why not send your workforce on a followership programme...?). But more seriously, what kind of institutional and decision making structure does this fixation on leadership imply?

I fear that it is a top-down 'management style', with the man at the top (usually the man) being the key player and determining the fortunes of the organisation. That is of course one way of doing it, but it has tended to squeeze out competing and perhaps more effectiove models -- like the collaborative one. I'm not sure that when I am looking for, say, a Prime Minister, I really want a 'leader'. I think I would prefer a sensible and acute chair of the cabinet committee, whose members together can provide the expertise and the talents needed to guide the country. And I care more about his or her capacity to get to grips -- collaboratively -- with the big issues than to make a big splash with sparkling television performances. Of course, I am looking for a good level of competence in communication, but I am not looking for someone whose main talent is being plausible and funny in TV debates.

It makes me think of how my own Faculty in Cambridge is run, with considerable success in its own sphere. We are guided by a partly elected, partly selected Faculty Board of about 20 academic staff (plus librarian, student reps...). The Chair of the Board is elected for two years. It is a job that most academics expect to do once in their career, but not usually more. It is a short enough period of office to ensure that noone's research is too much interrupted by huge administrative responsibilities and to ensure also that those who are less good at the job (noone hopeless is ever elected) can do very limited damage. But it is long enough to let a Chair initiate and see through one or two reforms and changes. Even more important, by the law of averages, the Board at any one time includes a significant number of people who have themselves had the experience of having done the big job -- in other words there is a depth of experience among the members of the committee.

None of this is much in tune with modern univeristy governance, which is as committed to 'leadership' as any institutions, and works with an image of longterm super-profs providing that, top down, to us poor foot-soldiers. And I am sure that we will eventually be forced to scrap our system and go over to what I sometimes call the 'baronial' structure (after the colloquial term "science barons'). But it is worth sticking up while we have it for an old-fashioned (and maybe eventually radically new again) collaborative form of governance.

Whether the structures of organisation with a medium sized faculty in Cambridge provide a model for other institutions is a moot point. But they may be a better model than you might at first think. To put it another way, good schools may depend on good teachers rather more than they depend on good leadership. And good national government may depend more of good MPs and good structures of collaboration more than on a presidential style Prime Minister.

July 18, 2016

The slipperiness of democracy

Please don't misunderstand what follows. I am no fan of dictatorship, of Platonic government of philosophers, of hereditary ruling monarchies, or of military juntas. I feel as strongly as most of us that the government is best when it is by, with and of the people. But I also remember one of those eye-opening moments when I was a student, sometime around 1974 -- a moment delivered by Moses Finley, the awkward, clever and charismatic Professor of Ancient History in Cambridge back then. He was lecturing us on Greek (largely Athenian) democracy, about which most of us were pretty dewey eyed and not very hard-headed.

I still remember the penny dropping when he pointed out to us that there was hardly a country in the world, of many different political systems, that did not claim to be a 'democracy' -- it was often, he insisted, used as a term more of approval than of analysis. He went on to explain that the slogan 'power to the people' was a warm one, but there was no agreed way of judging whether the power had actually been delivered. Who has a political voice in the shape of a vote is one factor (though many people happily think of Britain as 'democratic' decades, if not centuries, before women had the vote). Who has political initiative, that is who can form policy, is another. Freedom of -- and equality of -- speech often gets put into the equation. You might also take equality of access to key resources which enable full participaton in the political process, such as education or healthcare. And then there are all the differences between a direct democracy (Athenian style), a representative democracy and a delegated one (that is to say, we currently elect representatives to govern according to their best judgement not delegates who must necessarily follow the will of their constituents on each issue).

It was in recognition of this lightbulb moment that I used to ask first years when we started on ancient democracy to think of how a spokesperson for the then German Democratic Republic (which we in the west almost universally regarded as tyranny) might defend its 'democratic' elements, or conversely how the USA of UK could be presented as having a glaring democratic deficit. At first they would look baffled, but very quickly -- even if only for the sake of argument -- they would start to wonder how to weigh up freedom of speech versus freedom of access to health care, and to discuss the hereditary elements in the UK parliament and the role of immense wealth in enabling US citizens to exercise political influence. One 'man' one vote, as their definiton of democracy would usually begin, was soon looking pretty inadequate.

We could do with Moses Finley around at the moment, and with the acerbic comments he would no doubt have about our current reactions to the complexity of democracy and its discontents, both at home and abroad. How it is that both main political parties could have become so beholden to the idea of the votes of their individual party members that we nearly had the Prime Minister of the country chosen by a relatively small group of paid-up Tory constituency party members (unrepresentative even of Tory voters) -- no matter that they might have gone against the views of the majority of the elected representatives who had been voted into office by a far less unrepresentative body of voters. And the Labour party seems to have almost sold the right to choose its leader to anyone who was prepared to pay a few quid for the privilege (whether putting the price up, as they have just done, is more of less democratic I wouldn't like to say). In their case, the system was partly designed to curb the power over party elections of the unions, which since Thatcher at least have often been portrayed as an anti-democratic force in British politics. In fact, it was the unions that in many cases provided 'democratic' access to political power for those outside the traditional elite, and offered a schooling in political debate and arguent that was as good as the Oxford Union. I've heard a couple of times over the last week that May's new cabinet is the first since Attlee's to have a majority of members who did not attend independent school. How did Attlee manage that, so many decades ago? Well I haven't done all the checking down to the last man (sic), but I would be very surprised if it wasnt union training that lay behind the success.

And as for the attempted coup in Turkey, not much nuance was on show, in the first few days at least, when we discussed what this meant for Turkish 'democracy' (as if, in any case, it was identical to our own). Most 'democratic' western 'leaders' deplored the attempted forcible overthrow of an elected 'democratic' government. And fair enough, government by the force of arms is hardly compatible with the rule of the people (many of whom, on both sides, tragically died). But then neither is imprisoning journalists, as has been going on in Turkey at ever increasing levels, or now dismissing and imprisoning judges. So does that make the coup legitimate? Well, it isn't as easy as that (if it was, there would be a lot of other countries where the military might feel justified to intervene). But it would be good to remember, before we so confidently pontificate, that democracy is not simply reducible to the idea of 'democratically elected governments', and it doesn't come in just one form, and -- lets face it -- historically it has been brought about in many ways, including violence. From the very beginning Athenian 'democracy' wasn't the result of gradual, peaceful reform; it was literally fought over. That was also something that Finley tried to get into the heads of us dewey eyed, over optimistic, and slighty naive students.

PS: When I was putting this together I found this excellent blog by Conor Farrington on the House of Lords and the possibilities of unelected democracies... worth reading.

July 14, 2016

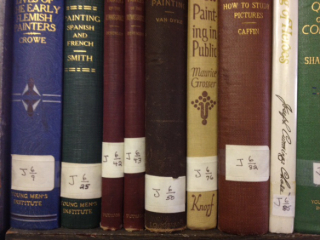

What happens to dead library books

In my current project (images of Roman emperors in Renaissance and later art) I am using a different variety of books from those that I am used to. And this means, in particular, that they are spread across different libraries in Cambridge and/or, in the case of art books, that they are available only in the 'non borrowable' section of the University Library. This has meant that I have tended to look more carefully at the books that might be available to buy. The savings in time might well be worth the exenditure in cash. And I have had quite good luck in finding some pretty arcane things quite reasonably. I tend, I confess, to use AbeBooks, owned by Amazon.

Over the last couple of weeks I found 4 books I really needed on the website: a reprint of the festival book of The Entertainment of Charles II -- 1662; an importantant study of an historic house and collection in N��rnberg, Der Hirsvogelsaal in N��rnberg; a collection of essays edited by A. MacGregor on The Late King's Goods (on the sale of Charles I's collections); and another reprint of a festival book, commemorating the Ceremonial Entry of Ernst Archduke of Austria into Antwerp, June 14, 1594.

Although it was actually made clear on the website, it was only when these turned up that I realised they were all ex-library books.

Now, I realise that libraries do have to weed books. And the two festival books might be thought surplus to requirements, given the excellent British Library website that 'publishes' many of these festival books, including this particular pair (though I still couldnt help wondering what Birkbeck College Library and Toronto Central Library had actually got for their surplus books, as I bought each one for not mch more than ��20). I guessed that I could forgive whatever Essex County Library it was that let The Late King's Goods go (it might be a bit of a niche market and my explorations suggest thst it is widely held in UK research libraries). But the same could not be said for Der Hirsvogelsaal in N��rnberg, which I bought for ��12.70 plus p and p.

This had been let go by the library of "Historic England" for a song presumably (else I wouldn't have bought it so cheap). And, so far as I could see, it is a book that otherwise in the UK is only in the library of the Courtauld Institute (it may lurk elsewhere, but that's what my quick researches sugest). If so there is something to worry about.. did noone at Historic England realise what a rare book they were flogging for so little? did they not offer it to a major research library (or was it turned down)?

Whatever, it does suggest to me that, while deaccessioning may sometimes be necessary, it might be done with a little more care for the holdngs of the country as a whole, with valuable books not just being made (as I suspect, but dont of course know) part of a job lot to a second hand book shop (excellent as the shop might be).

I guess I have it in my hands now, and probably when I have done with it I should give it to the Cambridge University Library.

July 11, 2016

Turkey, tourism and terrorism.

A week or so ago I was on holiday in Turkey, on a boat off the south coast. I didn't mention this at the time, as it always seems a slightly dangerous advert: 'house empty, burglars take note'. That may be a bit neurotic, but I do have in mind the first question that the police are supposed to ask: "who knew you were away?" I dont think that the response "anyone who has come across my blog, constable" would have won me much sympathy.

Anyway, we had a great week, seeing some old ancient favourite sites: like Knidos where the famous Aphrodite came from: Kaunos, which is a great town with some stunning rock-cut tombs, but if anything put in the shade by the wonderful reed beds (plus turtles, as you see above) through which you now  approach it (it's the tombs above the reed beds you can see on the right); and Aphrodisias, three hours inland but as spectacular an excavation as any in the last 50 years (and also, as it happens, where I first came across the husband). But a new place for us was the site of Loryma, an amazingly well-preserved Hellenistic fort. Forts dont usually do much for me, but this was dramatically special, as I hope you can get a sense, from this picture below:

approach it (it's the tombs above the reed beds you can see on the right); and Aphrodisias, three hours inland but as spectacular an excavation as any in the last 50 years (and also, as it happens, where I first came across the husband). But a new place for us was the site of Loryma, an amazingly well-preserved Hellenistic fort. Forts dont usually do much for me, but this was dramatically special, as I hope you can get a sense, from this picture below:

But there were more poignant aspects too. The south of Turkey relies heavily on tourism for its income and that has been badly hit by the knock on effects of terrorism. Bodrum still seems to be heaving with custom but almost everywhere else we went was at best half full, or nearly empty. OK, that was nice in a way for those of us who were there, but it is terrible news for the region's prosperity.

And while we were there, the terrible attack on Istanbul airport took place. We changed planes on the way back at Istanbul and saw the moving tribute to the victims in the concourse. An awful crime, and awful to think that -- whoever was responsible -- it works (of course it does) to keep people away. Whatever you think of the present government (and it was a shock, to put it euphemistically, to find Twitter blocked for the 24 hours after the attack: cui bono?) no country deserves this.

July 6, 2016

What we can say in support of Tony Blair

I have spent half of my adult life being either in love with, or at war with, Tony Blair. I'm going to come onto the 'war' bit later. But I do hope we remember that, although he made a colossal and almost unforgivable error, he did some very good things for this country. He presided over a redistributive governement (although they always tried to conceal quite how redistributive it was) and he brokered the Good Friday agreement -- and that will always be to his credit, whatever his other faults. Dont lets forget.

But I simply cannot understand how he can now be saying what he is saying about Iraq. For me, it just won't do to claim that the 'intelligence' misled the government. There were plenty of people saying loudly that the intelligence was not correct: Hans Blix for one and my local scientists for another. But in any case, it is the government's job to look critically at what MI6 and others say... not simply to take it as read. The idea that many people in the country correctly and for good reason distrusted the intelligence, while the government appears to have taken it on trust, is an indictment of our system and how it draws on expertise. How much of an indictment is hard to know, as Chilcot makes clear that there were an embarrassing lack of minutes at the upper levels.

This seems mad, my college catering committee produces decent minutes, which anyone can refer to -- and no doubt access under Freedom of Information (I wouldn't bother)... we go to war without proper minutes?

But I also can't understand the line, insisted on by Blair, that it all turned out to be more difficult than was expected in the post invasion 'game'. Isn't that what proper risk assessments are supposed to take account of... like what happens if something goes wrong, and where the weak points are. The idea that we went to war with what was apparently (and, yes, I am probably being unfair) not much more of a risk assessment than I would deploy when taking a group of students to Paris seems mind boggling. There might have been a Plan A, but what about B, C, and D?

I just wish that Tony Blair would fess up. I dont think that he is a bad man (I dont honestly think that there are as many 'bad men' in the world as we like to imagine). But his refusal to accept that many people looked at the 'evidence' provided, scutinised it, concluded that it didn't add up -- and then were ridiculed (we were) -- really irks.

The dissidents were right, and of course we are angry that we were systematically rubbished, as if we simply didn't understand. We did understand, and in this case we were smarter than our government.

(Is there a parallel with Brexit here? I suspect so.)

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers