John Cassidy's Blog, page 98

April 19, 2012

From “Nugent Goes Nuts” to “Bam Bites Dog”: The Phoney War of 2012

I take a few days off from the horse race to write about other things, and what happens? From one perspective, all sorts of stuff: Mitt Romney is overheard revealing his “secret” agenda to some campaign contributors in Palm Beach; gun-loving G.O.P. rocker Ted Nugent seemingly threatens to shoot the President if he is reëlected; the young Barack Obama is “revealed” as—wait for it—a consumer of canines. From another perspective, not very much happened at all. From Hilary Rosen-gate, to “Nugent Goes Nuts,” to “Bam Bites Dog”—well done to the woman or man who first tapped out that headline—the “Phoney War” of 2012 is upon us.

The only real news is on the front page of today’s Times. Barely a week after Rick Santorum dropped out of the G.O.P. primary, Romney is already benefitting from not having other Republicans attacking him every day. According to a new survey from the Times and CBS News, he and Obama are now tied in a head-to-head matchup. This finding validates the results of other recent polls, from Gallup and Pew Research, which also show Romney enjoying a bounce. (In the Gallup tracking poll, he is now leading the President by four points.)

Students of history will recall that the phrase “Phoney War” originated in the fall of 1939, when, though the Allies and the Axis powers were formally at war, there wasn’t very much actual fighting going on—not in Western Europe, at least. (In Poland, which Germany had invaded, and in Finland, which the Soviet Union attacked, plenty of blood was being spilled.) With the two armies staring each other down along the Maginot Line, their commanders were focussed on building up armaments, prosecuting the propaganda war, and engaging in limited skirmishes at sea.

With more than four months left until the conventions, which will presage a period of all-out political warfare, the two campaigns find themselves in a position analogous to that of the Allied and Axis commands in the months before May, 1940, when the Battle of France began. For both sides, the first order of the day is raising money for the serious fighting ahead—hence the endless round of thirty-six-thousand-dollar-a-plate dinners that Obama and Romney are attending. To fill the time between fund-raising events, and to give the campaign press something to report on, the candidates are already giving fall-style campaign speeches and criticizing each other. Wednesday’s public exchange went like this. Romney, from Charlottesville, North Carolina: Obama in “over his head” and “swimming in the wrong direction.” Obama, from Elyria, Ohio: Romney to “shower the wealthiest Americans with even more tax cuts.”

At this stage, none of these speeches can be expected to inflict serious damage on the opponent. They lack the amplifying effect of extensive television ads, and most voters are still concentrating on other things. Still, the campaign events allow each candidate to try out some zingers and put the other fellow on the defensive. Meanwhile, the spin doctors, political surrogates, negative research wallahs, and media maulers on both sides are engaging in more serious and nefarious work—the political equivalent of special ops. Most of it involves taking trivial incidents or remarks and seeking to inflate them into something larger. But the two sides are also busy looking for really damaging information, something that could conceivably swing the election.

The resulting dustups aren’t very edifying to watch. They do serve a purpose—it’s just not the public purpose. The campaigns get to trash each other; the campaign reporters get some fodder for Twitter; the cable talking heads get something to gab about; and commentators at serious sites such as this one get something to bemoan: the trivialization and cretinization of American politics. I’m as put off as anybody, but let’s be clear about one thing: it isn’t exactly new.

The first campaign I covered was in 1988: think Willie Horton, Boston Harbor, Michael Dukakis in a tank. When the old-school columnists Jack Germond and Jules Witcover wrote a book about the campaign they subtitled it: “The Trivial Pursuit of the Presidency 1988.” With the onset of war rooms and dedicated political sites and social media, the problem has gotten worse, but, hey, that’s how campaigns are fought these days. There are still plenty of serious stories and policy analyses being produced if you are prepared to search around a bit for them. But it’s Ted Nugent that gets the clicks.

In case you hadn’t heard, the Motor City motormouth’s ravings at an N.R.A. convention have earned him an interview with the Secret Service, which presumably won’t be restricted to soliciting his recommendations for Latin American whore houses. Nugent’s comments were far more offensive than anything Hilary Rosen said about Ann Romney’s career as a stay-at-home mom, but the fact that they came from a notorious wack job gives the Romney campaign some deniability. Rosen’s misfortune was that she was a more plausible figure, and she stepped on a land mine. Preserving the gender gap is essential to Obama’s prospects of reëlection; anything that carries the threat, however slight, of narrowing the gap is a serious matter—hence the speed with which the White House disassociated itself from Rosen.

Romney hasn’t disavowed his statements in Palm Beach, which reporters standing on a sidewalk outside the private fund- raiser overheard, and I’m not surprised. This story didn’t even rise to the status of a storm in a champagne glass. The presumptive G.O.P. nominee told some well-to-do backers that he was willing to eliminate some tax shelters that favor the rich, such as the deduction for interest paid upon mortgages for second homes. He also said that the G.O.P. needs to attract independent voters, women, and Hispanics, not just “true believers” who watch Fox, adding that he would run a campaign based squarely around “jobs and kids.”

Pivoting to the center and focussing on economics happens to be precisely what pundits and scribblers of all political stripes, myself included, have been advising Romney to do for months now. Big questions remain about whether he can pull it off, but he clearly knows what’s necessary. Democratic claims that his statements indicated the existence of a secret agenda were overblown. Republicans always tell their supporters they will slash spending and close down wasteful government departments. And, as my colleague Ryan Lizza noted a couple of days ago, it seldom happens.

The flap over “Bam bites dog” is somewhat different, and, in a way, more consequential. It originated in a column on the Daily Caller, a conservative Web site, by Sean Medlock, a blogger who writes under the pseudonym Jim Treacher. In a feat of intrepid reporting, Treacher pulled a passage from Obama’s 1995 memoir, “Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance,” about spending time with his stepfather, Lolo Soetoro, in Indonesia:

With Lolo, I learned how to eat small green chill peppers raw with dinner (plenty of rice), and, away from the dinner table, I was introduced to dog meat (tough), snake meat (tougher), and roasted grasshopper (crunchy). Like many Indonesians, Lolo followed a brand of Islam that could make room for the remnants of more ancient animist and Hindu faiths. He explained that a man took on the powers of whatever he ate: One day soon, he promised, he would bring home a piece of tiger meat for us to share.

From the G.O.P.’s perspective, reminding people of Obama’s cosmopolitan family history serves two purposes. In the immediate sense, it provides a riposte to Romney’s own shaggy-dog story: the infamous twelve-hour journey of his Irish setter, Seamus, on the roof rack of a family vehicle. “Obama would never put a dog on top of a car,” Treacher chortled. “Dries out the meat.”

But there’s also a bigger, less explicit message here, and it’s one that the Republicans and their surrogates have been alluding to for months: Obama isn’t like most Americans—he’s different, foreign, weird, a Europe-loving crypto-socialist, and perhaps even a closet Muslim. Despicable as it is, this whispering campaign is based on some sound political logic. With Obama’s unfavorability ratings already in the mid-forties, the G.O.P.’s best hope of defeating Obama is to drive them up further and make the election a referendum about him.

Nobody said wars, even Phoney Wars, were pretty or casualty-free. On October 14, 1939, a German U-boat quietly entered the British naval base at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands, and sank the battleship H.M.S. Royal Oak, killing more than eight hundred sailors. So far this year, none of the Republican or Democratic special ops have inflicted much lasting damage, but keep your eyes open. It was in the spring of 1988 that George W. Bush’s negative research team happened upon the story of how Willie Horton raped a woman and committed an armed robbery after getting out of jail on a weekend furlough, and it was in April, 2004, that the Swift Boat attacks on John Kerry began.

The Phoney War probably won’t decide the outcome of the election, but it isn’t wholly without consequence.

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

April 18, 2012

How to Occupy Washington

Off to D.C. to speak at a lunch event marking the launch of “The Occupy Handbook,” a wide-ranging collection of essays inspired by the anti-Wall Street, anti-inequality protest movement. The nine o’clock Acela is packed. Who says there is no market in this country for high-speed rail? Give Americans a reliable service with decent seats and wi-fi, and they’ll pay through the nose to use it. (My round-trip ticket cost almost five hundred dollars.)

As the train speeds through New Jersey and Delaware, I dip into some of the fifty-odd pieces in the “Handbook,” which the editor Janet Byrne, who has worked with Michael Lewis and many other writers, conceived and put together in impressively short order. In addition to calling on Lewis to interview himself and offer some advice to his fellow-one per centers on how to deal with annoying protesters, she persuaded luminaries ranging from Paul Volcker to Jeffrey Sachs to Scott Turow, as well as a wide assortment of lesser-known names (myself included), to contribute articles.

The subjects covered range from the anarchist roots of Occupy Wall Street, to the Spanish “Indignados,” to detailed proposals on how to reform the banking system and end the housing crisis. With any such collection, there is a danger of it coming out as a grab bag. But the recurring themes of overweening finance, rising inequality, and political capture that spurred much of the American public to express support for, if not actively participate in, the Occupy movement, gives the “Handbook” a reassuring thematic consistency. Many of the contributors, but not all, are indignant. The piece from Paul Volcker, the crusty former chairman of the Fed, “arrived on the same day as the songwriter Tom Verlaine’s interview with Rolling Stone journalist Matt Taibbi,” Byrne recalls in her introduction. “Paul Volcker and Matt Taibbi feel basically the same way about certain things.”

The event is at the Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics, on Massachusetts Avenue, near Dupont Circle. Fred Bergsten, the trade expert and longtime head of the institute, has gamely agreed to host a discussion that doesn’t fall under the institute’s normal rubric. In introducing the panel, he points out that the issues raised by O.W.S. aren’t going away, and they aren’t restricted to the United States.

The three other panel members are well-known academics who contributed to the “Handbook.” First up is Carmen Reinhart, a fellow at the Institute, who co-wrote a highly influential history of financial crises titled “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly.” Next in line are the economist Robin Wells, who, with her husband Paul Krugman, is the co-author of a popular economics textbook, and James Robinson, a political scientist at Harvard, who co-authored a new book, “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty,” which is getting a lot of attention.

An advantage of going last at such events is that you don’t have to say much; by the time your turn comes around, the audience is getting bored. A disadvantage is that if the other panelists are any good, and these ones are, they will cover most or all of the interesting things there are to say, leaving you bereft. Carmen provides a whistle-stop tour of the financial crisis and its legacy, arguing that we are still in the early stages of an extended period of sub-par growth. Robin details the alarming rise in income inequality, pointing out that it has coincided with a striking rise in political polarization. James talks about the importance of maintaining open, democratic systems of government, and resisting the “oligarchization” of American politics, which he says is an increasing danger.

I give a quick spiel about market failures in the financial sector, raising some of the themes from my own tome on economics and the financial crisis, and my article in the handbook, “What Good is Wall Street?” which first appeared in The New Yorker in November, 2010. Seeking to disguise the obvious as a profound insight, I also posit that we are living through a particularly interesting and open-ended point in history—one in which the neo-liberal consensus has collapsed but no new ruling ideology has arisen to replace it.

At a think tank named after a Wall Street billionaire, some hostile questions might have been expected in the Q. & A. session, but none materialize. Several people stand up and question whether the panel’s analysis was dystopian enough. A former staffer on the Senate Banking Committee asks why we didn’t mention corporate governance and the proliferation of big stock options granted to senior corporate executives. Another questioner asks James if he wasn’t being naïve in talking about the dangers of “oligarchization,” when that reality is already here. A chap from the International Labor Organization queries whether, in today’s globalized economy, it’s even realistic to talk of individual countries, such as the United States, tackling inequality and regulating the financial sector.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that the Occupy protests struck a chord in Washington. People who live and work there see how the system works up close. After the Q. & A. finishes, the former Senate staffer comes up and tells me how, during the nineteen-eighties and nineties, as C.E.O.s became almost entirely concerned with goosing quarterly profits and stock prices, their company’s legislative lobbying became more and more aggressive. Another audience member, who still works on Capitol Hill, reminds me that in both parties it is standard practice to allot seats on the House and Senate finance committees to members from marginal districts that need to raise a ton of money in campaign contributions.

O.W.S. hasn’t changed that practice or many others that are disfiguring the political system and preventing it from tackling the economic challenges that the country faces. It has changed the terms of the public debate, though. On the train back to New York, I read in the Times about Republicans on Capitol Hill maneuvering to prevent a vote on the “Buffett Rule,” which would raise taxes on the one per cent. On the front page of the paper, there is an article about Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, two French-born economists whose research on income distribution is now being discussed everywhere. (The “Handbook” contains an article by Saez and Peter Diamond, an M.I.T. professor, calling for a big increase in the tax rate on top incomes.)

The Occupy protesters may have gone home, at least for now, but the issues they highlighted are front and center. And if you want to find out more about them, I thoroughly recommend “The Occupy Handbook.”

April 17, 2012

Tax Day: What’s Up With Mitt’s Extension?

Today is the day to file your tax return and pay the government any money you owe it—we all got two extra days, thanks to Sunday and a local D.C. holiday—unless, like Mitt and Ann Romney, you have filed with the I.R.S. for an extension. In that case, you still have to pay however much you think you owe, but you don’t have to file an actual 1040 until six months after the normal April 15th deadline. Consequently, the Romneys now have until three weeks before the election to complete their return.

Confirmation that Romney had filed for an extension came on Friday evening—the point in the weekly news cycle when politicians traditionally release bad news. Naturally, the timing provoked suspicions that Romney was trying to hide something about his finances. Maybe he is—his campaign has refused to say exactly how much he is worth—but it seems unlikely that this was his reason for seeking an extension.

Back in January, Romney released his full tax return for 2010, when he and his wife earned $21.7 million, which was more than two hundred pages long. At the same time, he released an estimate of his tax return for last year, when he and Ann earned $20.9 million. Although not as detailed as the 2010 return, this document ran to more than ninety pages.

If there are things Romney is trying to keep to himself, they are unlikely to be found in his tax return, whenever it is finally published. Romney knew full well in 2011—and 2010, for that matter—that he would be expected to release his tax returns. It’s safe to assume that he arranged his finances in a manner most capable of withstanding public scrutiny.

Why, then, did he bother to ask for an extension? One likely reason, which his campaign cited, is that he doesn’t yet have all the financials details necessary to file a full return. As an investor in private-investment partnerships, Romney probably receives notice of precisely how much money he has made considerably later than most people do. Rather than sending out the standard W-9 forms, which many self-employed people rely upon to report their income, investment partnerships send out K-1 forms—and often they don’t do so until the second or third quarter of the year following the tax year in question. To avoid being hit with penalties, the wealthy folks who are affected by this practice routinely file for extensions, often basing their estimates on preliminary information provided by the partnerships. According to Romney’s campaign, he and his wife have done this in previous years.

Of course, Romney could have updated the 2011 information that he released in January and put it out there for all to see, specifying it was still preliminary. But there wasn’t really anything to be gained from doing so. Although the actual news value of the 2011 return would almost certainly have been minimal, its very existence would have prompted another flood of stories about the absurdly low tax rate that the Romneys face—13.8 per cent in 2010 and an estimated 15.2 per cent in 2011.

At a moment when the Mittster is desperately trying to put the primary race behind him and reboot his campaign, that was the last thing he needed. Much better to take a bit of heat over filing for an extension and subsequently release the tax return when it will cause the least amount of damage. Over to Chris Cillizza, at The Fix, who covered this admirably yesterday:

The campaign’s vagueness about when they might release the returns is intentional. It gives them considerable wiggle room to pick the right time—aka when no one is around or paying attention to politics—to put the returns out. (Early August, anyone?)

Put simply: The Romney team knows that the candidate’s tax returns are a political loser for them. The best way to deal with losing issues is minimize them to the greatest extent possible. Filing for an extension—whether that was by necessity or born of political calculation—to release his returns allows Romney to handpick that moment.

Romney’s taxes are going to be an issue all the way until election day. There is nothing he can do about that. But, at least for now, he isn’t going to give the Democrats any help in exploiting it.

Photograph by Scott Eells/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

April 16, 2012

Dr. Kim at the World Bank: It’s Time for Some Answers

To the uninitiated, today’s appointment of Dr. Jim Yong Kim, the head of Dartmouth College, as the next president of the World Bank, may have looked like an open and democratic process: through their representatives on the Bank’s board of directors, a hundred and eighty seven countries had a say. But this was really an election in the style of New York or Chicago a hundred years ago, with the U.S. government playing the role of Tammany Hall. The fix was in.

With the support of its European allies and Japan, the United States had just enough votes to push through its candidate. But the entire process—the outcome of which was essentially a foregone conclusion, due to a long-standing deal in which the U.S. gets to choose the Bank’s leadership, and Europe the I.M.F.’s—left many developing countries outraged. On Friday, José Antonio Campo, a former finance minister in Colombia, dropped out of the race, calling the selection process a “political exercise.” That left a straight choice between Kim and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the finance minister of Nigeria, who would have been the first woman and the first African to head the Bank. “You know this thing is not really being decided on merit.” Okonjo-Iweala told reporters before Kim’s appointment was announced. “It is voting with political weight and shares, and therefore the United States will get it.”

I have to confess, I don’t know quite what to make of all this. The choice of Kim over Okonjo-Iweala goes beyond personalities, or North-South rivalries. It goes to some big political and intellectual debates about the future of development policy.

Clearly, the selection process was something of a sham. Rather than appearing with Campo and Okonjo-Iweala at a public forum that the Washington-based Center for Global Development organized last week, Kim has been flying around the world, seeking the support of the Bank’s shareholders, particularly those in Russia, the one European country that could conceivably have voted against him. From his perspective, this was perfectly understandable. The Bank isn’t a charity or a debating club. It is a lending agency-cum-economic consultancy, and its seemingly peculiar voting structure, which gives the United States just over fourteen per cent of the vote, largely reflects the amount of capital that each country has contributed to the organization.

In any case, what really matters isn’t how the candidate is selected, but what the Bank can do to improve the lot of the world’s poorest people, and how its mission should change in a time when many formerly poor countries, such as China and India, are fast approaching middle-income status. From this perspective, the choice between Okonjo-Iweala and Kim and offered up an interesting paradox. The charismatic African woman represents the traditional approach to economic development, and the low-key Ivy League president represents a new approach—or, at least, he may. (Given that he’s said so little, nobody can be sure.)

The World Bank does a lot of things. It is involved in health care, education, and environmental issues. But, since its foundation, in 1944, its principal role has been in lending money, on favorable terms, to the governments of developing countries in order to finance things like roads, bridges, and irrigation projects, with the intention of spurring economic growth. There is a huge and contentious literature on how effective this approach has been. Optimists who hoped, early on, that poor countries could be put on a path to prosperity merely with capital from the Bank and other donors were disappointed. Some critics say most of the aid was wasted and only served to prop up corrupt governments. But in some places—such as Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya—there are World Bank success stories.

Today, the Bank follows a dual-track approach of financing much needed government investments and promoting market forces. If Okonjo-Iweala had gotten the job, she would certainly have continued this approach. Sometimes depicted as the radical choice, she is actually a consummate Bank insider. After gaining a PhD from M.I.T., in 1991, she has spent much of her career working there, eventually becoming a key deputy to Robert Zoellick, the Bank’s president. In a public letter supporting her candidacy, a number of former Bank staffers said she “would bring the combination of her experience as finance and foreign minister of a large and complex African country with her wide experience of working at all levels of the Bank’s hierarchy in different parts of the world, from agricultural economist to managing director.”

What will Kim do now that he’s got the job? In nominating him last month, President Obama said, “It’s time for a development professional to lead the world’s largest development agency.” That was stretching things. Kim is an expert in public health rather than economic development. To his great credit, he has worked on the ground in poor countries, such as Peru, building up public-health networks. But his experience in running big development organizations was restricted to two years as head of the AIDS/H.I.V. department at the World Health Organization. Over to Lant Pritchett, an economist at Harvard’s Kennedy School, who worked at the Bank for a decade:

There is a massive difference between doing development work and doing charity work to mitigate the consequences of the lack of development. Ngozi has done development work in many settings and in many positions both in Nigeria and within the World Bank. Jim deserves praise for having devoted his time, attention and expertise in medicine to improve the health care for people in the developing world—which is certainly one component of development—but his development experience is limited to one sector.

What little we do know of Kim’s views on economics and development isn’t wholly reassuring. In 2000, he co-authored the book “Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor,” which questioned the very premise of economic development—that increases in growth and G.D.P. generally improve human welfare. “The studies in this book present evidence that the quest for growth in GDP and corporate profits has in fact worsened the lives of millions of men and women,” Kim and two of his co-authors wrote in the introduction. In the conclusion, they added, “As the imperatives of growth at any cost increasingly determine economic and social policy and the behavior of global corporations, more people join the ranks of the poor and greater numbers suffer and die.”

After Bill Easterly, an N.Y.U. economist and development expert, pointed out these passages on his blog, Kim’s sponsors at the White House and the Treasury Department quickly put out the word that Kim strongly believes in promoting economic growth. Still, many development economists and Bank staffers fear that the choice of Kim might well represent a retreat from ambitious efforts to stimulate over-all development, and a shift towards tackling specific problems that are not necessarily economic, such as infectious diseases and malnutrition.

In an interesting post on the Bank’s economics blog, Michael Woolcock, a sociologist who has worked at the Bank since 1998, said it is facing a choice between “Big Development” and “Small Development.” (Thanks to the estimable Clive Crook for pointing me to this post.) “These two visions of development are not incompatible, and reasonable people can cast their lot with either one,” Woolcock wrote. “But the distinction between them matters and has significant consequences for how priorities are assigned, how resources are allocated, and difficult decisions are made.”

As president of the Bank, Kim will be responsible for shaping its over-all philosophy and helping to decide where its money is spent. I stick with what I said when his name was announced: he could turn out to be an inspired choice. We simply don’t know. At some point over the past month, he should have outlined the views and beliefs that he will be bringing with him to the post. Perhaps he wanted to say something but was told to hold his tongue. At this stage, it doesn’t really matter. But now that the Obama administration has successfully muscled him into office, there is no excuse for him prolonging his silence.

Photograph by Pedro Ladeira/AFP/Getty Images.

April 13, 2012

Inequality 101-B: Two Cheers for the Buffett Rule

As you might well have guessed if you read my previous post about the rising trend in pre-tax income inequality, I’m strongly in favor of using the tax system to level things out, at least somewhat. The Buffett Rule would do that, and I support it. The fact is that in recent years all too many of the very richest Americans haven’t been paying their fair share in taxes. This is a problem that needs addressing.

But my support isn’t unqualified. Viewed from the perspective of inequality and over-all tax policy, the Buffett Rule is very much a second-best, or third-best option. And it isn’t entirely clear to me how putting so much emphasis on this measure will help clear the way towards doing other things that need to be done, such as reversing at least some of the Bush tax cuts and treating income from investments more like other forms of income.

I regard the White House’s promotion of the Buffett Rule as largely a political move. That isn’t necessarily a criticism. Given the anti-tax mentality that still permeates American politics, rallying public support for higher taxes in any form, even those that fall on the very wealthy, isn’t easy. Teaming up with Warren Buffett, perhaps the most respected businessman in the country, was a smart decision by the White House.

Clearly, Congress isn’t going to pass Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s “Paying a Fair Share Act,” which contains a version of the Buffett Rule, and is due to come up for a vote on Saturday. The point is to get the G.O.P. on the record against the Buffett Rule and hold them accountable for that in the general election. If Republican politicians think it’s right that some very, very rich people, Mitt Romney included, pay a smaller share of their income to the federal government than some middle-income people do, they should have to explain why to the voters.

Spotting this trap, some Republicans are trying to dismiss the Buffett Rule on the grounds that it would raise just forty-five billion dollars over the next ten years, a pretty trivial figure compared to the budget deficits that are projected over that period. This argument can be challenged on two counts.

First, as the Washington Post’s Ezra Klein explained a couple of days ago, the forty-five-billion-dollar figure was calculated on the basis of a “current law” baseline, which assumes that the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of the year and that the Alternative Minimum Tax isn’t fiddled with—which it always is. If the calculation is carried out on the basis of the “current policy” remaining in effect, the Buffett Rule raises about a hundred and sixty billion dollars over ten years. In Klein’s words, “Still not enough to solve our deficit problems on its own, but nothing to sneeze at.”

The second point is that the Buffett Rule isn’t intended primarily as a deficit-reduction device. It is aimed at addressing a quirk of the current tax code that favors the very rich. As the White House’s National Economic Council explained in a briefing paper it put out the other day: “The Buffett Rule is the basic principle that no household making over $1 million annually should pay a smaller share of their income in taxes than middle-class families pay.” In short, this is primarily about fairness and equity, not revenue.

Even after all the giveaways to the rich that both parties have served up over the past three decades, the U.S. tax system remains a progressive one. For the most part, people with higher pre-tax incomes pay more of their earnings to the federal government than middle-income and low-income Americans. Some figures in the White House briefing paper make this clear. Among households earning between fifty thousand and a hundred thousand dollars a year, the average federal tax rate—including the taxes paid on all forms of income and social-security taxes—is thirteen per cent. Among households earning a hundred thousand to two hundred thousand dollars a year, the average tax rate is eighteen per cent. And among households earning a million to ten million, the average tax rate is twenty-six per cent.

On average, very high earners do pay more in taxes than their secretaries. But some of them, such as Buffett, don’t. Looking at average tax rates doesn’t give the full picture. There are middle-income people who pay as much as twenty per cent of their income to the federal government. Similarly, some million-dollar-plus earners pay as little as twelve per cent, and twenty-two thousand of them pay less than fifteen per cent. As you move into the very top reaches of income distribution—where people like hedge-fund managers, private-equity tycoons, and Wall Street C.E.O.s reside—there are more people, relatively speaking, who face very low tax rates. And when you get to the four hundred highest-income people in all of the country, you find that, in 2008, one in three of them paid less than fifteen per cent of their income in taxes.

I haven’t heard anybody present a coherent defense of this situation, which is what the Buffett Rule is intended to remedy. It supplements the A.M.T., which was originally designed to ensure that high-income people paid a reasonable level of taxes even after they had employed all of the legal tax dodges that their C.P.A.s could come up with. Under the new system, if a million-dollar-plus earner owed the federal government, say, just fifteen per cent of his (or her) income, the Buffett Rule would push the share he (or she) owed towards thirty per cent. (It isn’t clear yet exactly how much tax burdens would rise, since the White House hasn’t spelled out the full details of what it is proposing. Under Senator Whitehouse’s bill, the new higher tax rate would only apply to income after the first million dollars of a person’s earnings, and it wouldn’t hit thirty per cent until after the first two million dollars of earnings.)

Particularly in view of the fact that the very rich have already benefitted from a big rise in pre-tax incomes—see my previous post—such a proposal is perfectly reasonable. It merely deprives top earners of undue favors from the tax code. But my question for ardent supporters of the Buffett Rule is this: why not address the source of the problem, rather than its symptoms?

It is no mystery why people like Buffett don’t pay much in taxes. They receive most of their income in the form of capital gains and dividends, both of which are taxed at fifteen per cent. We could raise the taxes on investment income to twenty per cent or twenty-five per cent, which is what they used to be. We could also treat “unearned” income in the same way that we treat ordinary earnings, and tax it accordingly. If a household is in the twenty-five-per-cent income-tax bracket, it would pay twenty-five per cent tax on its dividend income; if it’s in the top income bracket, it would pay thirty-five per cent. Such a policy would restore progressivity to the tax system at the very top of the income distribution, and it would bring in a lot more revenue than the Buffett Rule.

Many neoclassical economists would argue that raising the tax rates on investment income would discourage investment, hinder productivity growth, and, eventually, lead to lower wages. But in the decades prior to 1997, we had considerably higher tax rates on capital gains, and capital investment as a percentage of G.D.P. was no lower than it is today—for much of the time, it was higher.

The White House would probably argue that raising taxes on investment income simply isn’t politically feasible. But, given that the Republicans in Congress currently have a veto on any tax legislation, that is true of virtually any progressive proposal. The question is what sort of doomed measure the President should seek to rally public support for, in the hope he will be able to pass it after the election. The Buffett Rule is a modest and simple proposal that appeals to common sense. Maybe the White House’s plan is to start small and build up from there. If so, the rule will serve a very useful purpose. But it shouldn’t be mistaken for a cure-all.

Photograph by Luke Sharrett/The New York Times.

April 12, 2012

Inequality 101: The Picket Fence and the Staircase

When a group of millionaires appear onstage with a Democratic President to call for higher taxes on people like them, you know one of two things: either the President is in Hollywood, or something interesting is happening in the country at large. In this case, it's the latter. After three decades in which rising inequality was largely ignored, it has finally emerged as a serious political issue—or, at least, President Obama is trying to turn it into one.

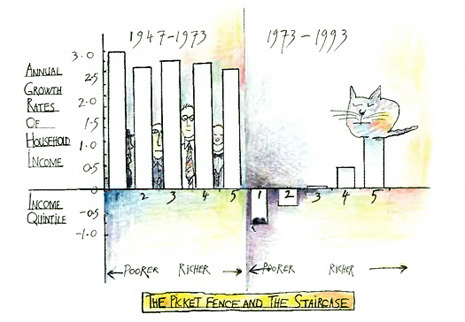

I'll have more to say later about the "Buffett Rule" that Obama has proposed, which would force people who make upwards of a million dollars a year to pay at least thirty per cent of their income to the federal government. But before getting into a policy discussion, I thought it might be useful to provide a reminder, with the aid of some charts, about the basic facts underlying the debate. As I said, rising inequality is hardly new. One of the first articles I published in the magazine, in October, 1995, was entitled "Who Killed the Middle Class?" It contained a chart I called "The Picket Fence and the Staircase."

The bar chart on the left shows how during the so-called "Golden Era" of 1947-1993, the inflation-adjusted incomes of the rich, the poor, and the middle class grew in a pretty similar manner—hence, it looks a bit like a picket fence. The bar chart for the period from 1973 to 1993 looks more like a staircase. During that time, the incomes of households in the bottom forty per cent of the income distribution actually fell, the middle stagnated, and upper-income households gained, but not as much as they had during the Golden Era. (I wasn't the first to use the picket-fence metaphor. I got the idea from Paul Krugman.)

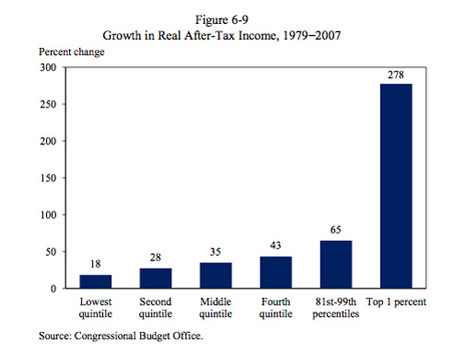

At that stage, it really did look like the rich were getting richer and the poor were getting poorer. Since the early nineteen-nineties, incomes at the bottom of the distribution have grown a bit, but not by much. Depending on which years you select, you can make the chart look a little different, but however you dice the numbers, the basic staircase pattern remains. Households in the upper parts of the distribution have seen their incomes grow a lot faster than poor and middle-income households. Chart 2, which covers the period from 1979 to 2007, shows this clearly.

I took this chart (and the ones that follow) from this year's Economic Report of the President, which the White House Council of Economic Advisers published in February. It also illustrates another interesting trend—one that bears directly on the debate about the Buffett Rule. At the very highest reaches of the income distribution—the top one per cent of households—incomes have skyrocketed. Between 1979 and 2007, the one per cent saw their incomes rise about eight times as much as those of middle-class households. But they also did a heck of a lot better than other well-to-do households that didn't quite make it into the top one per cent. Look at the right side of the chart. While the step up from the fourth tier to the fifth is pretty modest, the step up to the one per cent is huge.

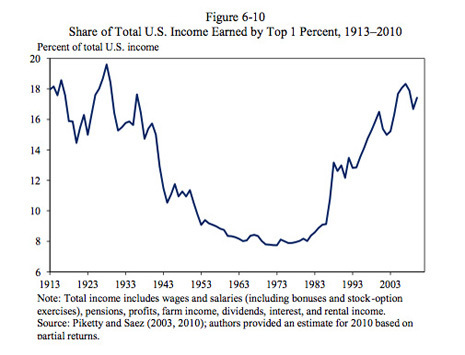

Another way to parse the data is to look at the share of over-all pre-tax income that each group receives. The pioneers in this area of research are Thomas Piketty, of the Paris School of Economics, and Emannuel Saez, of Berkeley, whose work is based on an analysis of income-tax filings. Chart 3 reproduces some of their figures.

One of the great virtues of the Piketty-Saez research is that it goes all the way back to 1913. If I had to pick a picture to illustrate the political economy of the United States over the last century, this would be the one. It shows the take of the very rich peaking in the late nineteen-twenties, at close to twenty per cent of total income, then falling sharply for forty years, only to turn back up in the late nineteen-seventies, and peak again in 2007. (On his Web site, Saez recently posted a useful synopsis of his and Piketty's findings. A detailed cross-country comparison of trends in top incomes can be found here.)

Any picture can only tell part of the story. What has caused the rise in pre-tax income inequality? Most neoclassical economists, who believe that remuneration is tied to productivity, emphasize the role of technical progress in raising the demand for skilled workers and enlarging the market that high-productivity individuals—"superstars"—can reach. Other economists stress the impact of globalization, particularly on low-skilled workers. Still others, and I would count myself among them, argue that the financial markets have played a big role. (It can hardly be a coincidence that the takeoff at the very top coincided with a huge bull market and a proliferation in stock-option grants for senior corporate executives.)

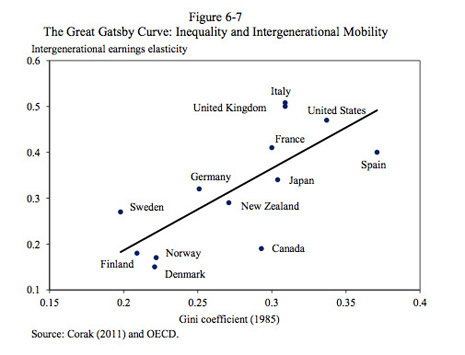

While the debate about the causes of rising inequality continues, we are learning more about its damaging consequences. Looking across countries, high levels of inequality tend to be associated with lower life expectancy, higher crime rates, and less social mobility, which for these purposes can be defined as the ability to move between income groups. For a nation that still takes the worldview of Horatio Alger seriously, the idea that America may actually be a highly stratified place in which all too many people get stuck at the bottom is hard to accept. But it is a fact—and not really a surprising one. Other countries that have a lot of income inequality also have low rates of social mobility. Chart 4 illustrates the relationship between the two phenomena for fourteen advanced countries.

The details of the chart are a bit complicated, but don't be put off. The horizontal axis shows a measure of income inequality: the Gini coefficient. A higher Gini indicates more inequality. The vertical axis shows a measure of social immobility—yes, immobility. The intergenerational-earnings elasticity gauges how closely an individual's earnings are tied to the earnings of his or her parents. A higher elasticity indicates less social mobility. The important thing is the trend line. In countries like Finland and Denmark, where incomes tend to be pretty equal, there is a lot of social mobility. In unequal countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, there is much less social mobility.

I should acknowledge that many conservatives still believe that inequality isn't anything to worry about. Some of them say that commonly used statistics, such as the ones I have cited, exaggerate the inequities in the U.S. economy. Others argue that inequality is healthy—a sign that innovation and entrepreneurship are being rewarded. But if you want to find out more about them, here are a couple of articles where you can do it. The first is by Diana Furchtgott-Roth, of the Manhattan Institute. The second is a PBS NewsHour interview with Richard Epstein, of the law school at N.Y.U.

I don't find these arguments convincing. In the words of the Economic Report of the President: "The confluence of rising inequality and low economic mobility over the past three decades poses a real threat to the future of the United States as a land of opportunity."

Photograph by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

April 11, 2012

Remembering Rick Santorum: Obama's Secret Weapon

Unlike most of you, I'm going to miss those woolen vests. At one point—I think it was after his victories in Louisiana and Mississippi, but I might be mistaken—there were at least three of them visible onstage. The candidate was wearing one, and so were two of his sons.

Say what you like about Rick Santorum and his quixotic campaign for the Presidency, which ended on Tuesday. He wasn't a slave to fashion. Nor was he a hostage to rich donors, modern dogmas (by modern, I mean post 1563, when the Council of Trent ended), or even to political ambition. If he'd had a bit more of the latter and a bit less religious zeal, he might just have knocked Mitt Romney out of the race.

Even though he didn't manage to do that, his campaign will have a lasting impact, but probably not the one he intended. In riling up liberal Democrats and turning millions of American women against the G.O.P., Santorum substantially increased the chances of President Obama being reëlected. If he wasn't so obviously a true believer, I would suspect that he was secretly in the pay of the Democratic National Committee.

As my colleague Ryan Lizza has already pointed out, Santorum will probably go down in the history books as a conservative protest candidate who appealed to evangelical Christians and few others—the heir to Pat Robertson, Pat Buchanan, and Mike Huckabee. But he could have been more than that. Let me jog your memory back to February 8th, the morning after he shocked Romney in Colorado, Minnesota, and Missouri. After that triple victory, Santorum had the opportunity to unite two key groups in the modern Republican coalition: culturally alienated evangelicals and economically alienated ethnic whites.

Obviously, there is some crossover between the two groups, but they remain distinct. The evangelicals tend to live in rural areas and vote on religious grounds. In this instance, many of them couldn't stomach voting for a Mormon. The ethnic whites live in suburban areas, and tend to respond to pocketbook issues, although these are often refracted through issues of race and ethnicity. Many of them weren't enthusiastic about nominating a leveraged-buyout tycoon.

Santorum definitely had a message that appealed to evangelicals. But he also started out as an economic populist of sorts, extolling his humble Irish-Italian heritage and talking about the need to revive American manufacturing. If you had dug into Santorum's economic plan, you would have discovered that it was a traditional Republican bait and switch, consisting largely of yet more tax breaks for rich individuals and corporations, but at least he knew how to present trickle-down economics in Reaganesque blather about protecting the interests of hard-working Americans—a trick Romney, with his fourteen per cent income tax rate, could never hope to pull off.

As Santorum got more and more media attention, he allowed his economic message to get lost in a welter of damaging publicity about his views on things like contraception, abortion, and gay rights. Rather than playing down the fire-and-brimstone stuff, which alienated many moderate Roman Catholics, never mind the rest of the population, he amped it up, engaging in a verbal battle with the White House over the issue of whether employers with religious affiliations should be obliged to offer women birth control. Then, in the run up to the crucial Michigan primary, he appeared to attack college education and the memory of John F. Kennedy. (In the wake of those dumb comments, even Bill O'Reilly chimed in against Santorum.)

If Romney had lost to Santorum in Michigan, one of his home states, his campaign, based as it was (and is) on the notion of his electability, may well have imploded. Even if that had happened, I don't think Santorum would have taken the G.O.P. nomination. Somebody less incendiary, such as Jeb Bush, would surely have entered the race and defeated him. But, my, what a kerfuffle there would have been.

Even after making a series of howlers, Santorum only lost Michigan to Romney by three points—forty-one per cent to thirty-eight per cent—and this despite being massively outspent. But once he had missed his chance in the Wolverine State, he never got another real opportunity to rewrite the media narrative.

On Super Tuesday, he did pretty well, winning in North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, but he lost another squeaker in Ohio, thus depriving him of bragging rights. After that, he was more or less obliged to win Illinois, where, once again, he simply didn't have the money or the organization to compete with Romney and his barrage of negative ads. It was almost as if Santorum preferred it that way. Rather than cultivating potential donors and bringing in an army of consultants, pollsters, and other political mercenaries, he continued to campaign like an insurgent—appearing at diners and bowling alleys, excoriating the Republican establishment, and buttonholing reporters who wrote things he didn't like.

And so, eventually, it came down to a choice: get out now with his head held high, or carry on with virtually no chance of winning the nomination, alienating many powerful Republicans whose support he might need for a future race, and facing the distinct possibly of being defeated in his home state.

Wisely, he chose the former course. "We have made history," he said on Tuesday in a thank-you message to his supporters on his Web site. Actually, he didn't quite make history. The G.O.P. primary is winding down precisely as was expected—in a victory for Romney. But Santorum came closer to knocking out Mr. Inevitable than most historians will acknowledge, and Barack Obama, for one, won't quickly forget his contribution to the Democratic cause.

Photograph by Eric Thayer/The New York Times.

April 10, 2012

After Santorum's Exit: Can Obama Be Beaten?

Now that Rick Santorum has quit the Republican primary, effectively leaving the nomination to Mitt Romney, this is a good moment to step back and look at where the general election stands.

Most political professionals, including many Republicans, think that President Obama will win reëlection handily—and this belief is reflected in the betting markets. At Ladbroke's, the British bookmaker, the odds on an Obama victory are four-to-nine, which means you have to bet ninety dollars to win forty. These odds imply that the chance of Obama winning is about sixty-nine per cent. At Intrade, an online-trading exchange, the implied probability of an Obama victory is a bit lower, but only a bit: sixty-one per cent.

Despite having been an early proponent of the view that things were shifting in Obama's direction, I am reluctant to embrace the new conventional wisdom that the result is virtually a foregone conclusion. If the past few months have taught us anything, it is that things can change pretty rapidly in American politics. Unlike Walter Mondale in 1984 or Bob Dole in 1996, Romney isn't a complete no-hoper. According to a new poll from ABC News and the Washington Post, three in four Americans still think that the economy is in recession, and, by a margin of four percentage points, voters trust Romney more than Obama to handle the economy.

Clearly, though, there has been a turn. Back in October, Obama's approval ratings were languishing in the low forties; head-to-head polls showed him lagging Romney in many battleground states, such as Florida; and the unemployment rate stood at 9.1 per cent. Since then, what a reversal of fortune we've seen. The Republicans have been attacking each other incessantly and driving up Romney's negative ratings; the economy and the stock market have both perked up; the unemployment rate has fallen to 8.2 per cent; and almost all of the polls have swung in the President's favor.

For ease of exposition, I'll divide the latest polling data into three areas: personal approval ratings; national polls; and state-by-state polls. In each case, I'll highlight the good news for Obama, and the bits of encouragement, if there are any, for the Republicans.

1. Personal Approval Ratings: Yesterday, Gallup's Frank Newport and Lydia Saad published an article highlighting how the President's approval rating has rebounded in the firm's daily tracking poll, which is the industry standard. Last fall, the monthly average hit a low of forty-one percent. In March, it reached forty-six percent, and last week, for the first time in a year, the three-day average hit fifty per cent. (According to today's update from Gallup, the approval rating is forty-four per cent. Because the daily numbers bounce around quite a bit, the weekly and monthly figures are more reliable.)

Other polling organizations also show Obama's approval ratings climbing back toward fifty per cent, which is widely regarded as a key threshold. (Since the Second World War, no President with an approval rating at or above that figure has failed to be reëlected.) For example, a new poll out today from ABC News/Washington Post shows it at fifty per cent exactly, up from forty-six per cent this time last month.

That's all positive news for Obama. At the same time, though, by historic standards his approval rating remains fairly low. In April, 1996, according to a Gallup poll, fifty-four per cent of Americans approved of the job Bill Clinton was doing. In April 2004, George W. Bush's approval rating was fifty-two per cent. Obama looks more vulnerable than either Clinton or Bush. Unfortunately for the G.O.P., he doesn't seem as vulnerable as Jimmy Carter or George H. W. Bush, the last two incumbents who went down to defeat. At this stage of their Presidencies, Carter and George H. W. Bush both had sub-forty per cent approval ratings in the Gallup poll.

2. National Polls: The new ABC News/Washington Post poll shows Obama with a healthy seven-point lead over Romney in a head-to-head matchup: fifty-one per cent to forty-four per cent. To a greater or lesser extent, other polls deliver a similar message. According to the latest Real Clear Politics poll-of-polls, Obama is leading Romney by more than five points: 48.5 per cent to 43.2 per cent. At the start of the year, they were virtually tied.

About the only encouraging thing in these numbers for Romney is that after all the negative publicity he's received recently, he's still within striking distance. Candidates have come from further back than he is to win the Presidency. In May, 1988, according to a New York Times poll, Michael Dukakis was leading George H. W. Bush by ten points: forty-nine per cent to thirty-nine per cent. In the general election, Bush defeated Dukakis by almost eight points: 53.4 per cent to 45.7 per cent. (The parallel isn't exact, of course. As Ronald Reagan's Vice-President, Bush was essentially running as an incumbent.)

3. State-by-State Polls. Last week's poll from USA Today/Gallup showing Obama leading Romney by nine points—fifty-one per cent to forty-two per cent—in twelve battleground states got a lot of ink, and justifiably so. But it only confirmed the message that has been coming from individual surveys in places like Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania: Obama is surging.

Because of the electoral map, Florida is crucial—particularly to the Republicans. If Romney doesn't win there, it is very difficult to see him getting the two-hundred-and-seventy votes he needs. This would remain true even if he wins states like North Carolina and Virginia—traditional Republican strongholds that Obama won in 2008 and where he again is mounting a big challenge.

As recently as late January, Romney was polling pretty well in Florida. A Miami Herald/Mason Dixon poll showed him four points ahead. But according to a more recent survey by Quinnipiac University, he is now trailing Obama in a head-to-head matchup by seven points: forty-nine per cent to forty-two per cent. The same polling organization showed Obama leading Romney by six points in Ohio and three points in Pennsylvania. "President Barack Obama is on a roll in the key swing states," said Peter A. Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. "If the election were today, he would carry at least two states"—out of Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—"and if history repeats itself, that means he would be reëlected."

Conclusion: If the G.O.P. is to have any chance of taking back the White House, it needs to start turning around these numbers. Although Santorum's exit isn't likely to have much immediate impact on the polling data, it does give Romney an opportunity to reframe the race as a referendum on Obama rather than a contest among unpopular Republicans. At the same time, he can start to repair some of the damage that the primary race has done to his own standing. With the challenge from the right largely removed—there is still Newt—he should be able to tack back to the center, which, as the Etch A Sketch gaffe made clear, is what he was intending to do along.

Another urgent task is to narrow the gender gap, which Santorum, with his out-of-the-mainstream views on contraception and abortion, helped widen into a chasm. In the USA Today/Gallup poll, Romney was trailing Obama by a stunning eighteen points among women in battleground states. Inevitably, a lot of attention will be focussed on the possibility of Romney selecting a plausible Republican woman as his running mate. But where is she to be found? Most of the obvious candidates are very conservative. And as a former C.E.O. himself, he can hardly pick a moderate businesswoman like Meg Whitman or Carly Fiorina.

The choice of a Vice-Presidential candidate is just one of many challenges facing the Mittster. At long last, though, he's getting some encouraging news. The weak job figures for March removed the smiles from President Obama's economic advisers. Four days later, his main Republican opponent has bowed out of the race. With Santorum gone, the big media outlets will probably start treating Romney with a bit more respect—if only to build up the general election as an appealing story.

For this and other reasons, the race is likely to tighten up over the coming weeks and months. Like most of my fellow scribblers (and betters) I think Obama will ultimately come out the victor, but elections aren't decided in April. Lord help us, we have another two hundred and ten days of this stuff. So, let's calm down and see whether the Mittster can make a fist of it. After all, isn't he supposed to be a turnaround artist?

Photograph by Marc Serota/Getty Images.

April 6, 2012

Why the March Jobs Report May Be Misleading

On the face of things, the March employment report, which came in considerably weaker than expected, is bad news for the 12.7 million Americans who are still out of work; for the Obama campaign,which received a big boost by the uptick in payroll growth during prior months; and for commentators like me, who have argued that the pace of the recovery is picking up. The economy only created 120,000 jobs last month. The new report appeared to confirm the warnings of Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, who said the other day that the recent gains in employment might not be sustained.

But before Eric "Etch A Sketch" Fehrnstrom and his pals at Romney H.Q. up in Beantown start popping the champagne corks, they might want to get one of their numbers guys to take a look at the full release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. I did that over breakfast, and the closer I looked the more I came to suspect that this month's report might be an anomaly—a bit of statistical "noise" rather than a true signal of the economy's state. Of course, I may be guilty of downplaying evidence that doesn't fit with my previous analyses—talking my book, as they say on Wall Street—but before junking the optimistic outlook I adopted towards the end of last year and reverting to my default state as a dour Yorkshireman, I'd want to see at least another month of job figures.

Here's why:

1. Our old friend sampling error. It's perfectly possible that non-farm payrolls actually increased by 200,000 last month, rather than 120,000. In an economy of three hundred million people, the Bureau of Labor Statistics can't hope to monitor every business in the country. It samples about 140,000 of them and hopes that the results are representative. Thanks to the laws of statistics, it can say with some confidence (ninety per cent confidence, to be exact) that the payroll figures are accurate to within 100,000. But it can't say more than this. All that can be said for sure is this: there is a very good chance that economy created between 20,000 and 220,000 jobs last month.

2. Seasonal adjustment. Every month, the Labor Department adjusts the raw figures to reflect seasonal factors, such as the fact that at the end of the summer many vacation camps and motels close down for the winter. This is perfectly sensible and legitimate. But some economists suspect that the unusually warm winter may have affected seasonal hiring patterns and played havoc with the government's adjustments. Two of the weakest areas of the job market last month were sectors where seasonal hiring and firing plays a big role: retailing, which shed 33,800 jobs; and temporary-help services, which, after big gains in previous months, shed 7,500 jobs. One plausible story is that because of the warm weather, businesses didn't lay off as many workers as they usually do over the winter, which meant they didn't have to hire as many people as spring arrived. After the statistical adjustments are made, this would show up in the official figures as a pick-up in hiring over the winter and a slowdown around now.

3. Other surveys are more upbeat. Only two days ago, ADP, a private research firm, said that the private sector added 209,000 jobs in March. ADP said that almost half of these jobs were created by small businesses, which the government statisticians have difficulty tracking.

The latest figures for jobless claims are also somewhat at odds with today's report. Just yesterday, the government reported that in the week ending March 31st, initial jobless claims fell to 357,000, the lowest level in four years. If the labor market was hitting a bumpy patch, you would expect this figure to increase rather than fall.

4. The decline in part-time working. Every month, the government carries out a second survey of the labor market, questioning households rather than firms about their employment status—hence it's called "the household survey." The headline figure from this month's household survey was actually pretty terrible. It showed employment falling by 31,000 in March, compared to a gain of nearly 400,000 in February. But the household survey also showed a dramatic decline last month in the number of people working part-time because they couldn't find full-time work. This figure dropped by almost 450,000. A decline in part-time working is almost always a good sign for the economy: it suggests more people are finding full-time jobs.

Of course, if the economy is picking up and more part-time workers are finding full-time employment, you would expect overall employment to be growing pretty rapidly. According to both the payroll survey and the household survey, it isn't. That's another reason this month's figures are a bit puzzling and should be treated with caution.

If we get another weak report next month, it will be time for a rethink.

Photograph by Eddie Seal/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

April 5, 2012

Obama's Game Plan: Let's Make This All About the Republicans

After my quick sports break, it's back to politics, and the duelling speeches by President Obama and Mitt Romney that everybody and his or her grandmother has seized upon as the start of the 2012 campaign proper. On Tuesday, B.H.O. lambasted W.M.R. (the "W" is for "Willard") for embracing House Republicans' slash-and-burn budget, which he described as "antithetical to the our entire history as a land of opportunity." Twenty-four hours later, W.M.R. lambasted B.H.O. for hiding his true agenda and engaging in a "hide-and-seek campaign."

If you want to get a flavor of what is at stake in the election, it's well worth reading the two speeches in their entirety. Obama presented the latest iteration of the populist platform he began laying out in Osawtomie, Kansas, last December and continued in the State of the Union, reaffirming the need for government activism to stimulate economic growth and social mobility, while ameliorating poverty and other failures of the market. Romney made a traditional Republican defense of free enterprise, low taxes, and smaller government, asserting that "freedom and opportunity will be on the ballot."

What got the headlines, of course, were the personal attacks, which marked the first head-to-head exchange of the campaign. Predictably enough, both sides accused each other of engaging in misrepresentation. Romney said Obama had "railed against arguments no one is making—and criticized policies no one is proposing," and accused him of "setting up straw men to distract from his record." The White House fired back, saying it was Romney who had something to hide, and that he'd been "willfully vague" about the policies he'd implement were he to be elected.

Behind the banter, something serious is going on. Obama didn't have to come out slugging at Romney this early. He's already well ahead in the polls, and the presumptive G.O.P. nominee-elect has been doing a pretty good job of goofing up without any assistance from the White House. But in the wake of the disastrous G.O.P. primary race—disastrous for the Republicans, that is—the Obama campaign has spotted a strategic opportunity that it is eager to seize upon.

It is a truism in political science that whenever a President runs for reëlection, the race ultimately turns into a referendum on his character and his performance. In normal times, this works out well for the incumbent. Americans are generally predisposed to like their Commander-in-Chief, and over any given four-year period the American economy usually expands, which mitigates the desire to throw him out. Statistical studies of past elections suggest that incumbency is worth perhaps two or three percentage points on Election Day, and this is often enough to ensure victory for the sitting President. As Rick Santorum pointed out the other night, only once in the past hundred years has a Republican contender defeated a Democratic President who was running for reëlection—1980, when Ronald Reagan sent Jimmy Carter back to Georgia.

It is no coincidence that the late nineteen-seventies were a period of economic strife: high inflation, rising oil prices, stubbornly high unemployment. About the only circumstance in which incumbency isn't a big advantage is when the country is in dire economic straits. The nightmare scenario for Obama, having taken over during a recession that turned out to be the worst since the Great Depression, has always been that he would turn into another Carter. If the general election had taken place in 2010, that might well have been his fate.

Things look considerably brighter now. Still, compared to past recoveries, this one has been pretty weak—too weak to dislodge the impression in the minds of many Americans that the country is going in the wrong direction. In such an environment, and with a candidate whose approval rating in the Gallup tracking poll has been stuck in the mid-forties (today it popped up to forty-nine per cent—we'll see if that rise is sustained), the White House is understandably eager to turn the election into a referendum on the Republican Party rather than a referendum on Obama.

Hence the sight of the President, who often goes for weeks on end without making any real news, going after the Supreme Court, then the House G.O.P. budget, and, finally, Romney himself. He was telling voters: This election is not just about me, or even primarily about me; it's about protecting the country from a bunch of crazed ideologues.

As it happens, the charges Obama levelled at his political enemies were largely true. The Supreme Court is in danger of engaging in precisely the kind of "judicial activism" that conservatives railed against for a generation or more. Paul Ryan's budget is a nutty right-wing manifesto rather than a serious proposal about how the country should tax and spend. And Romney did describe it as "marvellous"—one of his many recent slipups.

From the White House's point of view, that's a great thing about going after the Republicans. You don't even have to make things up. Every few days, it seems, one of the party's leading figures or prominent allies says or does something that can't stand up to serious scrutiny. Consequently, in the coming weeks and months, we can expect to hear more of the same from Obama.

Inevitably, the debate will shift back to the President's record on things like the economy, health care, and energy. But if in the meantime he can build up a big enough lead, and sow enough doubts about the Republicans in the minds of the voters, that might not matter very much. Come the summer, when Presidential races usually tighten up, the gap between the candidates could be just too big for Romney to close. That's what the Obama campaign is hoping for, anyway.

Photograph by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers