John Cassidy's Blog, page 94

July 9, 2012

Tax Wars: Will Romney’s Offshore Accounts Save the Progressive Principle?

Welcome back to work, Mitt!

The Mittster had barely gotten out of bed on Monday morning, following a weeklong vacation at his lakefront mansion in New Hampshire, before the liberal attack dogs began snapping at his well-tanned ankles. In his column in the Times, Paul Krugman demanded more information about Romney’s “very mysterious” financial holdings in offshore tax havens, such as Switzerland and the Cayman Islands. Appearing on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” Robert Gibbs, the former White House press secretary, also brought up these exotic locales, saying, “The American people deserve to know if he’s sheltering this money somewhere, or quite frankly, if he’s not paying the taxes he owes and the only way to do that is to release more tax returns.”

A few hours later, President Obama himself appeared at the White House and practically dared Romney to oppose his plan for the Bush tax cuts: extending the cuts for all households with an income below two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, while allowing Bush’s giveaways to those earning more than that to expire at the end of this year. “We don’t need any more trickle-down economics,” Obama said. “We need policies that grow and strengthen the middle class.”

If you suspect the whole thing was a blatant attempt to change the subject from Friday’s dismal job figures, award yourself a gold star courtesy of David Axelrod. In the “O Chicago” school of politics that Rupert Murdoch warned Romney about last week, the best form of defense is offense, and when it comes to attacking Romney there’s no better area to focus on than income taxes—his, and the rest of the country’s. But still, writing the whole thing off as a political stunt would be an error.

Behind today’s theatrics, two important and opposing principles are at stake: the principle that rich people should pay substantially more of their income in taxes, which underpinned American politics for almost a century; and the principle that a politician who endorses a tax increase of any kind is inviting certain defeat, which has dominated politics in Washington for much of the past decade. Obama is endeavoring to give new life to the first principle and overturn the second. If he succeeds, there will be a great irony—Romney and his byzantine personal finances will have played a significant role in saving the progressive-tax system.

The Obama campaign isn’t just trying to change the subject from jobs—although that is certainly part of it. It is rolling out a political strategy designed to make a debate about taxes that is potentially hazardous to Democrats into a much more favorable debate about just how rich and out-of-touch Mitt Romney is. (If your answers are “very” and “totally,” award yourself another gold star courtesy of Axelrod.) It’s a clever enough strategy, but one that is not without risks for the White House.

Two years ago, in the runup to the 2010 midterms, President Obama made exactly the same demands of Congress—and they backfired. The Republicans ignored the fact that he was calling for the preservation of a net tax cut for ninety-eight per cent of American households and depicted him as an old-fashioned tax-and-spend liberal. The message worked. To quote Obama, the Democrats got “a shellacking.”

What is different this time? Privately, some Democrats in Congress worry that the answer might be not very much. Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, both of them acutely sensitive to what happened in the midterms, reportedly favored making the cutoff for tax increases at least a million dollars, rather than two hundred and fifty thousand. In sticking with the lower figure, Obama and his advisers are betting that there is something very different between now and 2010—and that difference is Romney’s name at the top of the Republican ticket. Thanks to his absurdly low federal tax rate, his offshore accounts, and his refusal to disclose more than a couple of years of income-tax filings, Team Obama believes that Romney can be turned into a poster boy for everything that’s wrong with how the U.S. government raises money from its citizens.

The Mittster, bless his bright red jet ski, has invited it upon himself. He isn’t just “Mr. Fourteen Per Cent,” he’s a walking loophole. The scandalous “carried interest” deduction for managers of hedge funds and private equities; the artificially low rates on income derived from capital gains and dividends; the fancy accounting tricks, including the use of overseas accounts—Romney and family benefit from all of these (perfectly legal) blights on the tax system.

True, the “news” that he has parked some of his money offshore isn’t new at all, and it isn’t very “mysterious” either. The 2010 tax return that he put out earlier this year revealed the existence of his Swiss bank account, his investment company incorporated in Bermuda, and the fact that some of his Bain Capital related investments are held in Cayman Islands trusts. But the Obama campaign was merely waiting for an opportune time to exploit these revelations; and what better moment could there be than the first business day after the third straight set of poor jobs figures?

The Romney campaign’s response was predictable. “Unseemly and disgusting” was the phrase one flack used to describe Gibbs’s suggestion that the G.O.P. candidate was a serial tax avoider. Following Obama’s appearance at the White House, the Romney campaign put out another statement saying, “Americans are struggling in a ‘zombie economy’ and President Obama’s only answer is to pass one of the largest tax hikes in history.”

Thus, the battle lines are drawn. Which side wins will help shape the tax system for years to come. If it’s Obama, we are heading back towards the Clinton era, which, as the President pointed out, was a period of low unemployment and record budget surpluses. If it’s the G.O.P., the anti-tax brigade will have won another huge victory, with some pretty dire consequences for inequality and fiscal solvency.

Photograph by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

July 6, 2012

Jobs Report: Obama Needs Some Help

Another “Jobs Friday,” another set of disappointing figures for the White House. But before getting to the political spin, of which there will be plenty, it is worth setting down some of the pertinent facts and considering where things go from here. What happens to the labor market during the next four months is of much greater import for the election than anything that Mitt Romney, Barack Obama, or anybody else says today.

So here goes:

According to the Labor Department’s survey of firm’s payrolls, the economy created just eighty thousand jobs in June. If these figures are taken at face value, the economy has recently stumbled pretty badly. Between January and March, it created, on average, two hundred and twenty-six thousand jobs each month. Between April and June, the rate of job growth fell by almost two-thirds, to an average of seventy-five thousand jobs a month—a pretty dismal figure for what is supposedly a “recovery.”

The unemployment rate, which the Labor Department calculated on the basis of a different survey, this one of households, stayed steady in June, at 8.2 per cent. The household survey showed more jobs being created—a hundred and twenty-eight thousand of them—but a similar expansion in the labor force kept the unemployment rate steady. Between last summer and April of this year, the unemployment rate fell a full percentage point, from 9.1 per cent to 8.1 per cent, Since then, it has stayed pretty constant.

Last month, 12.7 million Americans were looking for work, about the same as in May. Another 8.2 million people were working part-time because business was slack or they couldn’t find a full-time job. And another 2.5 million people wanted a job but hadn’t actively sought one during the past month. If you add all these unfortunate folks together, the so-called “under-employment” rate stands at 15.1 per cent, which is about where it has been for the past few months.

Looking across the economy, there are few signs of real vigor. The private sector added just eighty-four thousand jobs last month, according to the payroll survey, and the government sector shed another four thousand jobs. The only businesses that did any serious hiring were temporary-help services, which added twenty-five thousand jobs. Manufacturing did O.K., adding eleven thousand jobs. But construction and retail were flat, as was the health-care industry, which hitherto had been a big source of job growth.

About the only really good news in the report was that people who still have a job are working slightly longer hours, suggesting that the economy is still expanding, albeit slowly. Hourly earnings also ticked up a bit. There is little indication here of another recession starting before the election, which would be the White House’s nightmare scenario. Equally, though, there is no sign of a pick-up in growth, or of the unemployment rate falling below eight per cent, which is an important figure psychologically and politically.

A few months ago, economists and political strategists close to the Administration were talking about going into the fall campaign with unemployment in the mid-sevens and trending down. Now, Obama faces a much tougher prospect: seeking to become the first President in modern times to win reëlection with an unemployment rate of eight per cent or higher.

It still may not come to that. There are four more jobs reports before the election, and some of them could bring better news. But for that to happen, Obama will need some outside help. Many other economic indicators, such as retail sales and factory orders, are also showing weakness. Fiscal policy is deadlocked. Absent a sudden turnaround in Europe, which seems unlikely, the President’s two best hopes are the Federal Reserve and the statisticians at the Labor Department.

After these job figures, Ben Bernanke is practically obliged to do something. At a press conference a couple of weeks ago, he explicitly stated that if weakness in the labor market persisted, the Fed would take more action to boost the economy. Unfortunately for Obama, the next Fed policy meeting isn’t until the end of this month. At that gathering, I think Bernanke will overrule objections from some of his colleagues and push through a third round of quantitative easing—a process in which the Fed effectively prints hundreds of billions of dollars and uses them to purchase bonds.

Some economists are highly skeptical about quantitative easing, which has already been tried twice. I agree with Bernanke that it provides some modest support to an ailing economy. If the Fed were to announce a big QE3 program at its next meeting, long-term interest rates would come down a bit, the value of the dollar would fall, and the stock market would probably get a temporary boost. All of these things should increase spending and hiring, but not by very much—the skeptics are right about that.

And even if the Fed does shift to a more aggressive stance, it will take some time—several months at least—for this policy change to show up in the jobs statistics. Obama needs a more immediate improvement. Conceivably, he could still find it in something I’ve written about before: “seasonal adjustment.”

If you examine the job figures over the past six months, rather than the past three months, they don’t look too bad: over the longer period, the economy has created an average of a hundred and fifty thousand jobs a month. That’s enough to accommodate the expansion in the labor force due to population growth, and a bit more. If the actual payroll figure, month by month, had come in at around a hundred and fifty thousand, the popular perception would be that a modest economic recovery was still on track, and Obama would be in a far stronger position politically.

But that didn’t happen. From January to June, the monthly payroll figures came in like this: 284,000, 259,000, 154,000, 68,000, 77,000, 80,000. That’s a pretty drastic fall-off. Some of it reflects the fact that G.D.P. growth has slowed down and businesses have put hiring decisions on hold. But some of it is almost certainly a statistical aberration caused by the abnormally warm winter, which led to fewer seasonal layoffs than normal during the cold months and fewer seasonal hires during the spring. If that is the case, the official job figures should pick up a bit in the coming months regardless of what happens to the rest of the economy.

The statisticians at the Labor Department make an adjustment for seasonal hiring and firing, which involves bumping up the raw payroll figures in the winter and knocking them down a bit in the spring. Normally, such a procedure is perfectly justified. This year, though, it appears to have overstated job growth during the winter and understated it during the spring. Recently, the official payroll figures have been quite a bit lower than the jobs numbers from other sources, such as the Labor Department’s own household survey and estimates provided by the research firm ADP. Just yesterday, ADP said that private sector employment expanded by 176,000 in June, which was more than double today’s payroll figure.

In short, it appears that things were never as good as they seemed a few months ago, and they aren’t quite as bad they appear today. With summer here, the seasonal-adjustment factor should drop out of the payroll figures beginning with this month’s figures, which will be released in the first week of August. Whether that will be enough to save Obama, is, of course, a completely different question. Even if he gets a bit of a boost from the statisticians, the President will still be lumbered with an economy that is now four and a half years into the most extended period of sub-par growth since the nineteen-thirties.

No wonder he is rolling out a “Plan B.”

Photograph by Sam Hodgson/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

July 3, 2012

In Close Race, Obama’s Plan B Is Paying Off

With the July 4th holiday upon us, both Presidential campaigns have reasons to be encouraged. After a slew of negative economic news and worrying poll numbers in April and May, Barack Obama has had a good few weeks, and the Supreme Court’s ruling on health-care reform capped it off. Chief Justice John Roberts’s legal two-step cruelly robbed Mitt Romney of the opportunity to portray his rival as a quasi-socialist violator of the Constitution. But the G.O.P. candidate is still in a much stronger position than he was three months ago, when he scraped through the Wisconsin primary and finally brought to an end Rick Santorum’s candidacy.

Both sides have said that the election is going to be close, and there is no reason to doubt it. For now, though, the momentum is running in favor of Obama, who is taking a few days off before embarking a bus tour of Ohio and Pennsylvania. His victory in the high court buoyed the spirits of everyone in Democratic Party, and it wasn’t the only good news that last week brought him. A number of opinion polls taken before the Supreme Court’s decision suggested that his campaign’s Plan B, which was adopted in wake of the economic slowdown earlier this year, is starting to bear fruit.

Plan A was to say that the hard slog of the past four years had been worth it, and that the economy was finally recovering. For an incumbent, this is a pretty standard message: things are getting better—stick with me. Over the winter, when job growth appeared to be perking up, it looked like a winning strategy, but then came the job figures for March, April, and May, which showed the growth in payrolls falling sharply. This Friday, the Labor Department will release the job report for June. Wall Street is expecting the payroll figure to come in at about a hundred thousand. Anything below seventy-five thousand would be another big blow to the White House; anything over a hundred and fifty thousand would be bad news for Romney, whose campaign has gone all in on the notion that the economy needs a new savior.

The Obama campaign’s Plan B is based on the assumption that the economy will continue to stutter along without slipping, once again, into an outright slump, which would probably insure a Romney victory. The basic idea is to try to neutralize the economic headwinds by changing the subject as often as possible, and by raising doubts about Romney’s record, both at Bain Capital and as the governor of Massachusetts. “We’ve got to make sure people fully appreciate Mitt Romney is not some safe alternative,” David Plouffe, one of Obama’s senior advisers, told the Times. Assuming the economy doesn’t get any worse, Obama’s strategists believe that they can eke out a narrow victory by mobilizing the same coalition that the campaign relied on in 2008—young people, minorities, women, and highly educated professionals—and by turning enough white working-class voters against Romney to deprive him of the surge in the Midwest that he needs in order to win.

A month ago, with the national and battleground state polls showing Romney cutting into Obama’s lead—and in some places surpassing him—Plan B seemed like wishful thinking. More recently, however, the polls have shifted in Obama’s favor. In the national head-to-head match, the Real Clear Politics average of recent polls shows him leading Romney, 47.6 per cent to 44.1 per cent. On June 18th, just two weeks ago, the difference between the two candidates was less than one percentage point. Now, an Obama lead of 3.5 percentage points shouldn’t be exaggerated: Romney is still within striking distance. But his post-primary surge seems to have come to an end, and recent local polling suggests that he is facing difficulties in some key battleground states.

A survey by Quinnipiac University of voters in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania showed Obama ahead in all three states—by four points, nine points, and six points, respectively. If Obama wins all three states in November, he will be virtually assured of victory. Even if he wins two out of three, he will be very well placed.

In Florida in particular, Obama’s recent gambit on immigration policy appears to be paying off. Among Hispanic voters, his lead over Romney has increased from ten points before the immigration announcement to twenty-four points, according to the Quinnipiac poll. This surge in Hispanic support is enough to give Obama a four-point lead in the head-to-head matchup, despite the fact that his approval rating among Floridians as a whole (forty seven per cent) is still lower than his disapproval rating (forty nine per cent).

In Ohio, meanwhile, which is a must-win state for Romney, Obama’s hefty lead is based on his strong support among women, blacks, and independents. According to Quinnipiac, the gender gap is a stunning fifteen points. Among female voters, Obama leads Romney fifty per cent to thirty-five per cent. He is also doing a good job of attracting support from independents, where he leads by nine points. These are alarming figures for Romney. If he loses Ohio, the electoral-college math becomes forbidding. Obama’s support among Ohio women and independents is so strong that it almost makes up for his chronic weakness among white men, which has always been his biggest vulnerability. Among white voters of both sexes, he is now trailing Romney by just four points: forty-five per cent to forty-one per cent.

What is driving these figures? Ohio’s economy is doing fairly well, and that is certainly helping Obama, but so is the fact that Romney just isn’t popular there. His favorability rating is thirty-two per cent, according to Quinnipiac, and his unfavorability rating is forty-six per cent. The Obama campaign believes that its negative ads about Bain Capital, which have running in Ohio and other states during recent weeks, are having the desired effect, and that might well be true. In the latest NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll of voters in swing states, one in three of them said that seeing or hearing about Romney’s business record made them view him more negatively, and just one in six said that it made them take a more positive view of him.

It’s no secret that negative advertising works, or that the Mittster has his problems with Joe Sixpack. His campaign’s primary response will be to double up on its own attacks on Obama, whose favorability rating in Ohio of fifty per cent is a whopping eighteen points higher than Romney’s. With the wads of cash that are flowing into the coffers of the G.O.P. campaign and its allied Super PACs, viewers in Ohio and other swing states won’t be able to turn on their television sets this summer without seeing another spot impugning the President and his works.

One of the indictments will be that he passed Obamacare: the Supreme Court ruling won’t change that. But it has already changed the political dynamics surrounding the health-care issue. After three months of setbacks and the emergence of internal squabbling about his campaign strategy, the President badly needed a win, and he got a huge one. Regardless of all the polling that shows the individual mandate is still unpopular, that victory should not be underestimated.

Had the Court thrown out the Affordable Care Act, or large chunks of it, Obama would have looked ineffectual and weak, and the G.O.P. attack dogs would have stepped up their assault on him as Jimmy Carter redux. Thanks to the Roberts ruling, Obama now has two historic achievements to fall back on, one domestic (establishing the principle that everyone is entitled to adequate health care) and one foreign (the killing of Osama bin Laden). People can still argue about whether his tenure has been a success or a failure, but nobody can dispute the fact it looks a good deal bigger and more substantial than it did a week ago.

Despite the near-panic that broke out in Democratic circles a few weeks ago when Romney drew even in some national polls, Obama has remained the betting market’s choice. At Intrade, the online prediction site, the implied probability of an Obama victory is about fifty-six per cent. Interestingly, at Ladbrokes, the British bookie, he is a firmer favorite: the odds on him winning are 8-15. (Bet a hundred and fifty dollars to win eighty dollars.)

Of course, betting markets sometimes get things wrong, and the Obama campaign isn’t celebrating yet. The President’s approval ratings nationally are still too low to assure him of victory, and his strategy of forsaking an over-all campaign theme in favor of patching together a coalition on the basis of a number of different targeted messages is a risky one. Romney, by contrast, is focussing almost exclusively on the economy. If the last few weeks have demonstrated anything, it is that the momentum of a campaign can reverse itself quickly. In fact, things could change again as early as this Friday— “jobs Friday.”

But even after all those qualifications, President Obama will enjoy his Independence Day break. For the first time in months, the skinny guy has his opponents on the defensive.

Photograph by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

June 29, 2012

John Roberts and Mitt Romney: Two Peas in a Pod

Après Roberts, le déluge.

A day on, liberals are still busy celebrating, conservatives are fulminating, and the pundits are issuing instant judgments, many of which have about as much foundation as a dissent from Samuel Alito. On CNN, for example, Gloria Berger echoed the G.O.P. line that yesterday’s ruling would turn November’s election into a referendum on Obamacare, while David Gergen doubted whether Mitt Romney would be able to ride this old nag all the way to the White House.

My two cents are with Gergen, and not simply because a diligent Obama researcher has dredged up some footage from as recently as 2009 in which the Mittster expresses support for the individual mandate, saying it would help bring down costs and encourage personal responsibility—although that video, to be sure, is pretty embarrassing. Rick Santorum was right. If the G.O.P. is going to base its campaign on overturning Obamacare, Romney is about the least suitable person there is to have at the top of the ticket.

Looking at things from a more cosmic perspective, though, it is perfectly fitting to have the man who introduced the model for Obamacare leading the charge to repeal it. And it is just as fitting that it was a conservative Chief Justice—ruling on what he claimed to be traditional conservative grounds (deference to the legislature)—who upended the conservative campaign to declare health-care reform unconstitutional.

The politics and economics of health care are plain wacky. From the moment, in early 2009, when Obama backed away from the public option and embraced Romneycare, things have been turned upside down, with liberals supporting a costly and hideously complicated giveaway to the health-care industry, and conservatives depicting a reform that originated at the Heritage Foundation as a socialist takeover. People on both sides are spouting claims that five years ago they would have dismissed as arrant nonsense.

Given this level of madness, the fact that Chief Justice Roberts would write a wacky upside-down ruling, which left legal scholars on all sides scratching their heads, shouldn’t have come as such a surprise. Roberts clearly wants to go down in history as a principled conservative rather than a G.O.P. henchman, or, as my old pal and office neighbor Rick Hertzberg cleverly put it: “A Burke, not a burka.” In rejecting the Commerce Clause justification for the individual mandate and seizing upon the tax argument, which Donald Verrilli, the much maligned Solictor General, had cleverly offered up as a get-out clause, the Chief Justice managed to have his cake and eat it. He preserved the Court’s good name, or what’s left of it, while simultaneously striking another blow against Wickard v. Filburn, the 1942 ruling that is to economic conservatives what Roe v. Wade is to social conservatives.

Nobody said that Roberts was dumb, and nobody said Mitt was, either. In many ways, they are very similar: two old-style, pro-business, prep-school Republicans, whose career advancement has depended upon their ability to attract the support of right-wing ideologues. Both grew up in the Midwest as the sons of corporate executives, and both received religious educations. Roberts went to La Lumiere, a Roman Catholic boarding school in Indiana. Romney went to Brigham Young. Both attended Harvard and rose quickly in their professional careers.

As men of conservative inclinations, but who are ultimately ambitious pragmatists, Roberts and Romney have both found it necessary to adopt the rhetoric of the hard right, and some of its policies, while trying to preserve for themselves some wiggle room. Although Romney said he disagreed with Roberts’ ruling, he must have admired the clever way in which the Chief Justice crafted it. Acting like the management consultant that Romney once was, Roberts dispassionately analyzed the constraints he was facing and crafted a strategy to do what he deemed necessary.

The big difference between Roberts and Romney is that the former, as Chief Justice, already has some freedom to maneuver. Since succeeding Rehnquist, in 2005, he has adopted a stance that amounts to two steps forward, one step back for the conservative movement. On most cases, particularly those involving challenges to corporations, he votes with the Scalito-Thomas bloc. But on some big issues that have the potential to bring the reputation of the court into disrepute—immigration and health care come to mind—he occasionally sides with the moderates and liberals.

Romney, whose campaign is partly dependent on the enthusiasm and ground work of conservative activists, still can’t stray too far from right-wing dogma—as evidenced by his failure to offer Hispanic voters anything positive on immigration reform. But if Romney were to reach the Oval Office, he would probably follow a strategy similar to Roberts’s, espousing conservative views but, when it came to acting rather than talking, hewing to the center on some big issues. My colleague Ryan Lizza has already pointed out that his pledge to repeal Obamacare beginning on the first day of his Administration is largely a political ploy. With the G.O.P. all but certain not to gain a sixty-vote majority in the Senate, there is virtually no prospect of the upper house voting to repeal health-care reform. The same thing applies to other policy proposals close to conservatives’ hearts, such as repealing the Dodd-Frank financial-reform bill and privatizing social security.

With the gridlock on Capitol Hill all but sure to continue, Romney would be in much the same spot that Obama has been in since 2010: reduced to negotiating with his enemies on the big issues—the deficit, taxes, and also health care—while introducing some relatively minor polices he can enact through executive fiat. I suspect that Romney might even like being penned in. As long as the Democrats have a blocking minority in the Senate, he would have a ready-made excuse for why he can’t start dismantling entitlement programs and shutting down entire government departments. As with Roberts’s tenure at the high court, the general tenor of a Romney Presidency would be conservative, but he would end up disappointing some of the ultras.

Of course, that is all assuming that the Mittster gets elected, which, in my view, is somewhat less likely than it was a week ago. But that is a subject for another post

Read the New Yorker’s full coverage of the Supreme Court’s historic health-care decision.

Photograph by Steve Pyke.

June 28, 2012

SCOTUS Ruling Stuns Romney and Fox News Posse

My oh my, this is fun. Who knew that watching the Fox News Channel could be so enjoyable?

Like certain others in the cable universe, the folks at 1211 Sixth Avenue began their coverage of the Supreme Court ruling by reporting that the individual mandate had been overturned. But then came the realization that John Roberts, the man in whom the entire conservative movement had placed its faith, the man who addressed the Federalist Society’s twenty-fifth anniversary gala, for goodness sakes, had gone over to the other side.

Appearing from his home state of Texas, Karl Rove looked ashen. For a moment, I thought he was going to accuse Roberts of treachery and call for his impeachment by the House of Representatives. Instead, speaking in funereal tones, he described the Court’s decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act on the grounds that the individual mandate was effectively a tax as “an extraordinary step.” And he went on:

It is a boost to the President, but it doesn’t make the controversy go away. In fact, it probably enhances the controversy . Clearly, this will now be a dispute between the two candidates.

Rove wasn’t the only homie in the “fair and balanced” posse who was desperately looking for a silver lining. Bret Baier, a Fox anchor, thought he had found one in the Court’s ruling on the Medicaid provision, which appeared to give the states some latitude. “Can the states opt out” of the entire bill? Baier asked. “That is the key point.” It was left to Shannon Bream, Fox’s reporter outside the Supreme Court, to disappoint Baier’s hopes. No, she said, the language of the ruling wasn’t that broad.

Oh well, never mind. There was always Fox’s new poll, which showed that six in ten Americans view the individual mandate as a violation of their civil rights. The network’s producers quickly highlighted that finding in a box at the bottom of the screen. And there was also the founder of Fox News, Rupert Murdoch, who had graciously agreed to be interviewed, supposedly to talk about his decision to split News Corp. into two: a film and broadcasting company, and a publishing company. Donning his political pundit’s cap, the great man showed he was perfectly capable of doing Rove’s job, if necessary: “It may not be a win [for Obama] when it comes to the election and voting,” he said. “We don’t know.”

Murdoch was quite right, but that is for the future. On this day, nothing could disguise the fact that the Supreme Court had delivered to Obama a monumental victory. Conservatives awoke this morning believing that the Court would uphold their claims that the President wasn’t fit to hold office—that he wasn’t just an incompetent and a quasi-socialist, he was a violator of the Constitution. Far from giving this narrative an official imprimatur, Chief Justice Roberts tossed it into the Potomac. And to add insult to injury, he quoted Benjamin Franklin, a sacred figure on the right, to support his arguments.

No wonder Republicans were stunned. Senator Marco Rubio popped up on the screen and said that, going into November, the ruling would energize the Tea Party and the rest of the G.O.P. “We are back where we were when I ran for office in 2010,” he declared. Then came Mitt Romney, who had also travelled to Capitol Hill for the decision. But rather than saluting it and joining in a conservative victory celebration, the Mittster was obliged to ape one of Rubio’s fired up Teabaggers.

After pledging to do what the Justices hadn’t, and move on his first day in office to repeal Obamacare, Romney trotted out some of his standard blather from the campaign stump, about it being a “job killer” that would “put the federal government between you and your doctor.” However, illustrating the ambiguous politics of the issue, he also felt obliged to point out that he was in favor of some of the popular parts of the bill, such as forcing insurers to cover people with preëxisting conditions.

Finally, it was Obama’s turn to deliver a speech he may not have been expecting to make. With his opponent’s face already bloodied, he declined to rub it in the dirt. He didn’t even mention Romney by name. Speaking from a lectern in the East Room of the White House, he acted all Presidential, pointing out some of the attractive features of the Affordable Care Act, and noting, in a subdued voice, that “the highest court in the land has now spoken.”

Indeed, it has. Now it’s the turn of the politicians, and who knows how it will all play out. After Obama had finished talking, Ed Henry, Fox’s senior White House correspondent, who is generally a straight-shooting reporter, noted that the unexpected ruling could give Obama a “shot in the arm” following a disastrous June. But Henry also had a bit of news to share. The chairman of the Iowa Republican Party had just accused Obama of lying repeatedly to the American people when, during the passage of health-care reform, he insisted that the individual mandate, and its accompanying penalties, didn’t constitute a tax.

Aha! Obama the tax bogeyman. Now, there’s a formulation that Fox News contributors and viewers alike can unite around. “That is going to be a big political weapon going forward,” Henry said.

Read the New Yorker’s full coverage of the Supreme Court’s historic health-care decision.

Photograph by Ken Cedeno/Corbis.

June 27, 2012

Health Care and the Supremes: Why the Right Has Already Won

On the eve of the Supreme Court’s decision on Obamacare, here’s a message to all the conservative activists out there, for whom this day has been a long time coming: Hats off to you! Unlike many of your opponents, you know how to build and sustain a political movement.

No, really: I mean it. Though the case against Obamacare that the Court is considering is a legal travesty, lacking in serious foundation, the moment is truly momentous. After thirty years of organizing, strategizing, and mobilizing, the conservative counter-revolution may be about to win its biggest victory yet: the striking down of a massive new government program, and, equally important, the overthrowing of a legal doctrine that Administrations of both parties have relied on for seventy years to regulate the economy.

Quite rightly, much of the discussion in the next few days will focus on the contents of the Court’s ruling, and its likely impact on the health-care industry, the rest of the economy, and the Presidential election. But before all that begins, it is worth taking a step back and surveying the historical landscape.

In his award-winning 2008 book, “The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law,” Steven M. Teles, a political scientist who is now at Johns Hopkins, begins with an internal White House memo from 1972, in which Pat Buchanan, who was then an aide to Richard Nixon, wrote of the high court: “The president has all but recaptured the institution from the Left; His four appointments”—Warren Burger, Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, and William Rehnquist—“have halted much of its social experimentation, and the next four years should see this second branch of government become an ally and defender of the values in which this president and his constituency believe.”

Buchanan’s hopes would “soon be proven sorely misplaced,” Teles notes. Under Chief Justice Burger, the Court upheld and expanded many of the landmark judgments of the previous four decades, expanding civil rights, upholding federal anti-trust statutes, and crimping the power of the states to defy national laws. It also legalized abortion in Roe v. Wade, a decision authored by one of Nixon’s appointees, Blackmun, and joined by two others, Burger and Powell. It would take another thirty-odd years and the building of a dedicated and (largely) unified conservative legal movement to forge a Supreme Court court with the majority and the self-confidence necessary to start rolling back the liberal agenda of the New Deal and the Great Society.

The history of this movement is broadly familiar. For those who need a refresher on the rise of the law-and-economics approach to jurisprudence, which provided it with a (slightly) updated free-market economic ideology, and the Federalist Society, which helped nurture its personnel, Teles’s book is a good place to begin. But the most valuable contribution Teles makes lies in his analysis of why the right-wing legal movement has proved so successful.

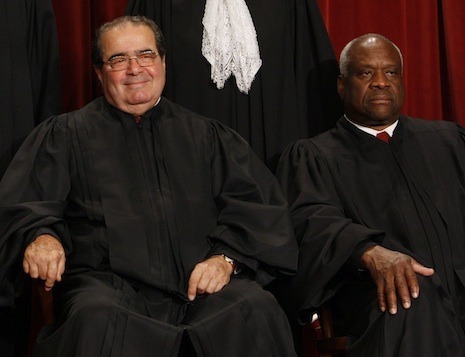

Unlike most accounts, which often focus on prominent individuals, such as Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia, or specific ideas, such as the doctrine of “strict constructionalism,” Teles concentrates on institutional and organizational factors. Conducting the battle of ideas was only part of the right’s strategy—a part, it could be said, that never really succeeded. Witness the contempt with which many top legal authorities regard the theories underpinning the constitutional challenge to health-care reform. Most constitutional scholars believe the 1942 Wickard v. Filburn ruling established the federal government’s right, under the Commerce Clause, to regulate any form of economic activity that affects the national economy at large. Since the health-care industry accounts for about a sixth of G.D.P., it is ridiculous to question Congress’s right to determine how it operates.

Still, the right looks like it will end up winning, and even if it doesn’t it will launch other challenges. What it realized after the disappointments of the nineteen-seventies was that having conservative legal ideas alone wasn’t enough. Faced with active opposition from the American Bar Association, law schools, and think tanks, the right needed other weapons. In Teles’s words, “Ideas need networks through which they can be shared and nurtured, organizations to connect them to problems and to diffuse them to political actors, and patrons to provide resources for these supporting conditions.”

Once these things were put in place, which by the mid-eighties they had been, the conservative legal movement was well placed. It would win some battles and lose others, but over the long haul, if it stuck to the task doggedly enough, momentum would shift in its favor. Back in the late eighties, the defeat of Robert Bork’s nomination to the high court was widely interpreted as a crushing defeat for the original-intent and law-and-economics crowd. But they kept at it, consistently nominating conservative candidates, not just to the Supreme Court but to the lower courts, too.

Ultimately, the fact that Bork and other luminaries, such as Richard Posner, never made it to the high court didn’t ultimately matter very much. In Scalia, Thomas, Roberts, and Alito, the right found four ardent disciples who would carry out its retrogressive agenda. In the lower courts, progress was, if anything, even more impressive. Over the years, so many conservatives were appointed that, inevitably, the opponents of Obamacare could find some judges willing to countenance their novel and somewhat crackpot theories. As Ezra Klein has pointed out, several of the leading lights of the conservative legal movement actually ruled in favor of Obamacare. It didn’t matter. When the conservatives lost in one court, they moved on to another.

What are the lesson of all this for liberals and progressives?

One is that perseverance counts. Rome wasn’t built it in a day, and neither was the conservative counter-revolution. The Olin Foundation began supporting the emerging school of law and economics in the mid-seventies, and the Federalist Society dates back to 1982. (Its Web site features a video of Chief Justice Roberts addressing its twenty-fifth anniversary gala, in 2007.)

Another is that opportunism is a virtue. Ten years ago, five years ago even, many conservatives and Republicans supported the idea of an individual mandate to purchase health insurance. Today, they are questioning its constitutionality, and exploiting popular opposition to it in order to try and bring down Obama’s Presidency. Liberals tend to get caught up in the pursuit of purist solutions: the public option, public financing of elections, a comprehensive climate-change treaty. Conservatives are more tactical. They win battles where they can.

A third lesson is that it is important to avoid infighting, long the bane of liberal and progressive movements. The right-wing legal world has its internal differences, too: libertarians versus business conservatives versus social conservatives. But to an impressive degree, the movement has been able to mask these differences in the interest of pursuing of common goals.

Finally, a period of adversity and exile is healthy for any political movement. It was the great liberal successes of the nineteen-fifties and sixties, under the aegis of the Warren Court, which inspired many conservative lawyers to take up the cause. The Roberts court, with its ruling in the Citizens United case, and now, quite possibly, in the Obamacare cases, may well be laying the groundwork for a similar reaction—this time on the center and the left.

We can only hope that this proves to be the case. But if the conservative ascendancy is to be forcibly challenged, still less upended, liberals and progressives will need to show some of the qualities that the right has demonstrated over the past few decades: energy, discipline, endurance, and the will to fight. History isn’t a procession or a debating contest—it is a struggle. Ask Bork or Scalia.

Photograph by Charles Dharapak/AP Photo.

June 25, 2012

SCOTUS Gives Hope to Both Sides on Health Care

On your marks, get set, go! Oh no, sorry: false start. That sound must have come from somebody in the crowd. Come back on Thursday at the same time for the real starting pistol.

So much for “health-care Monday,” which had Washington and the media world in a rare tizzy. Shortly after ten o’clock this morning, John Roberts and his colleagues handed down a bunch of rulings, some of them significant, such as one that struck down part of the Arizona immigration law, but none of them pertaining to the Affordable Health Care for America Act, a.k.a. Obamacare. The Justices, like producers of a Hollywood soap opera, were keeping their best plot twist for the end.

Pity all the politicians and professional agitators, such as Michele Bachmann, who (see the front page of this morning’s Times) had rushed back to a sweltering Washington in order to avail the world of their opinions on the court’s ruling—as if we didn’t already know them. (Last fall, Bachmann said the health-care reform would “endanger the national security.”) Pity, too, for the hordes of reporters and pundits who were hunched over their Twitter screens primed for action.

Isn’t digital technology supposed to increase productivity? How, then, do you explain hundreds of highly educated people—many of them highly paid, too—all devoting their workday to trying to outdo each other by a second or two, with a newsbreak or “witticism.” When the Arizona ruling came down, there was mass confusion about whether the court had ruled for or against the Obama Administration. (It was the former.) One of the few worthwhile comments I saw came from my colleague Ryan Lizza: “SCOTUS decisions are not really designed to be covered as breaking news, are they?”

The actual rulings, as opposed to the posturing and online blather, turned out to be pretty interesting. Take the Arizona case, in which the Court largely accepted the Administration’s argument that states can’t override federal immigration laws. (My colleague Alex Koppelman has written about the ruling in more detail.) How encouraging was it for the White House to see the three ultra-conservatives—Justices Scalia, Alito, and Thomas—reduced to a minority, and an angry one at that? Scalia’s stinging dissent, a defense of states’ “sovereign rights” that could have been written a hundred years ago, was almost as long as the majority opinion, which Justice Kennedy wrote.

The Arizona ruling showed, once again, that the Court’s right wing isn’t always a united phalanx: that’s the good news for the Administration and its supporters. Chief Justice Roberts, together with the four liberal Justices, joined Kennedy’s opinion. On most issues, though, Roberts, Kennedy, Scalia, Alito, and Thomas still see eye to eye. In asserting, by a five-to-four ruling, that its 2010 Citizens United ruling applies to campaign finance in Montana and other states, as well as to national campaigns, the conservative Justices demonstrated, once again, that they don’t shy away from public controversy—or of being accused of legislating by decree.

The Administration’s entire strategy in arguing the health-care case has been to create a cleavage between Justice Kennedy and the three conservative ultras, in the belief that Chief Justice Roberts would then side with the majority to avoid a five-to-four ruling. Back in March, after the oral arguments took place, I expressed the opinion that Donald Verrilli, the solicitor general, who was widely criticized for his performance, actually did a pretty good job of providing Kennedy with a conservative rationale for siding with the Administration. Rather than asserting a blanket federal right to introduce purchasing mandates, Verrilli argued that health care, for a variety of reasons, was a special case.

After this morning’s rulings, Verrilli still has some reason to hope that his narrow strategy might succeed. In the Arizona case, the court largely deferred to precedent. If it were to do the same thing in the health-care case, the case law on the interstate commerce cause would mitigate against striking down Obamacare, or even just outlawing the individual mandate. Still, though, most of the pundits are convinced that the Court will rule against the Administration.

We shall see. Don’t forget: same time, same place on Thursday for the final episode. There’s a rumor going around Twitter that Bobby Ewing may come back from the dead…

Photograph by Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images.

June 22, 2012

Germany Crushes Greece—This Time at Soccer

Now we know what it takes to get Angela Merkel, the famously cautious and phlegmatic Iron Chancellor, to leap into action and show some emotion: a rocket from the boot of a German soccer player in a quarter-final game at Euro 2012.

When Philipp Lahm, Germany’s captain, cracked a shot into Greece’s goal in the thirty-eighth minute of the so-called “Bailout Game” on Friday night in Gdansk, Merkel jumped up from her seat in the stands, raised her arms above her head, and cheered like any other jubilant supporter. Sporting the same lime-green top she had been wearing in Rome earlier in the day, where she had been meeting with François Hollande and other European leaders to decide what to do next in the debt crisis, Merkel swapped high-fives with the head of the German soccer federation, who was in the next seat to her. The Greek fans, who earlier had booed and hissed when Merkel’s face appeared on a big screen, were reduced to silence.

They would have their moment of joy—a goal by Giorgios Samaras (no relation to Antonis Samaras, the country’s new Prime Minister-elect) in the fifty-fifth minute which tied the game and prompted one English play-by-play announcer to declare, “Greece have wiped the debt out!” But the Greek celebrations didn’t last. Seven minutes after Greece scored, Sami Khedira, a strapping German midfielder, booted home a thunderous volley, and, a few minutes later, one of his colleagues, Marco Reus, scored with a similarly fearsome shot. The Greeks, down three-to-one, were on their way out of the tournament, the second most important in world soccer.

At the end, the score was four-to-two, which sounds respectable. But in truth, the game was just as one-sided as the bailout talks, with the Germans dominating from start to finish. At halftime, Alexi Lalas, the fiery Greek-American soccer icon, who was doing pundit duties on ESPN, said that for the Greek team the highlight of the first period had been the very first kick of the game. “They had a very good kickoff,” Lalas commented sarcastically. When, in the second half, the Germans scored a fourth goal, to lead by four-to-one, Ian Dark, ESPN’s play-by-play man, commented, “The danger for Greece is this gets humiliating.”

The Greeks know all about humiliations at the hands of Germany, of course, and they aren’t above drawing on the historic ones as well as the more recent. As a story on the BBC before the game noted, Greek newspapers have repeatedly depicted Merkel in an S.S. uniform, and opinion polls suggest that seven in ten of them subscribe to the idea that Germany is intent on creating a “Fourth Reich.” With resentments of this nature close to the surface, and with Greece’s own far-right parties on the rise, it was inevitable that the soccer showdown in Gdansk would attract a lot of attention. But the game was played in a good spirit, and there were no reports of trouble between the rival supporters.

As the game drew to a close, the former England star Steven McManaman, who suffered several defeats at German hands during his career, said, “There’s no shame losing to a wonderful German team. No shame at all. The Greeks can go home with their heads held high.” In sporting terms, he was undoubtedly right. But will the Greeks see it that way? One sign in the Greek section of the stadium featured a picture of the European Championship cup that will go to the winner of the tournament, and the words: “You can have our billions—but not the trophy.”

The sign was probably wrong on both counts. It’s not likely that Greece will ever repay the tens of billions of euros they owe to foreign lenders, the Germans included. (Most of the payments they’re currently making are themselves funded by the bailout loans.) And the German team, based on this performance at least, looks to have a very good chance of lifting the trophy.

Photograph by Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images.

June 21, 2012

Will Demography Save Obama?

In addition to prognosticating and spouting off on a daily basis, I’ve decided to post some in-depth interviews with campaign officials, politicians, policy wonks, and others with something worthwhile to say. The first one, which you can read in full below, is with Ruy Teixeira, a senior fellow at Center for Economic Progress, a progressive Washington think tank, who writes and edits the Democratic Strategist blog.

An expert on demography and polling data, Teixeira co-authored a very influential 2002 book titled “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” which argued that the Republican era that started in the late nineteen-sixties was coming to an end.

Many of the things that Teixeira and his co-author John Judis identified ten years ago—the rising number of Hispanic voters, an emerging gender gap between the two parties, and a shift to the Democrats among urban professionals—played into Obama’s victory in 2008. Despite Republican gains in the 2010 midterms and Mitt Romney’s recent rise in the polls, Teixeira believes that Obama is still well placed on the basis of demography and geography. “All the trends we identified that helped lead to Obama’s 2008 victory have continued apace,” he told me.

The rapidly growing Hispanic vote is particularly important, Teixeira insists. In Nevada, for example, it is now close to forty per cent. And Mitt Romney, after taking a hard line against illegal immigration during the primaries, has no credible way to reach Hispanics. “I think they’re stuck, and I think they know they are stuck,” Teixeira said.

With the gender gap also holding up, and with popular attitudes to things like gay marriage steadily becoming more liberal, Teixeira says that the election is shaping up as a contest between demography and economics. “All majorities are contingent,” he said. “Just because there’s a potentially dominant coalition emerging, one that has a secure vote and demographic foundation, doesn’t mean it’s going to win every election.” Romney’s strategy is to exploit popular unease about the economy. For Obama, “the question for him is whether he can leverage those demographic advantages and turn them into a victory in a situation that’s really quite difficult for the incumbent.”

I spoke to Teixeira on Tuesday, grouping my questions under three headings: demography, geography, and public opinion/campaigning. Here is the Q. & A. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve edited it a bit here and there.)

DEMOGRAPHY

Hi Ruy, and thanks a lot for agreeing to talk with me. The obvious question is this: Is that emerging Democratic majority you wrote about still there today, and how far is it going to help with Obama’s reëlection campaign?

Yes, not only is it still in place, it’s still growing. All the trends we identified that helped lead to Obama’s 2008 victory have continued apace.

Let’s go through a few of those. The three main demographic groups you identified were Hispanics, women, and urban professionals. How’s it looking on each of those?

O.K., well let’s start with minorities. Now, we argued in the book that the growth of minorities would benefit the Democrats. We certainly saw that in 2008 when you had twenty-six per cent of voters being minorities and eighty per centof them voting for Obama. Now, if we look at the data since 2008, we see the eligible minority voter pool is continuing to grow at about the rate seen in the last period of time, which is roughly a half percentage point a year, or two percentage points over a Presidential election cycle. So we would expect, based on that, twenty-eight per cent of voters in 2012 would be minorities. The minority population is growing in general, though [it’s] primarily driven by Hispanics, who probably account for roughly sixty per cent, or more, of the growth in minority eligible voters. So that’s a huge deal, to have a group like that growing at that rate.

Obama’s recent gambit on illegal immigrants—saying the government won’t deport minors and people who grew up here. Is there any evidence yet on how that is playing with voters?

We actually have some polling data that just came out. We know that Latinos back it like crazy, so the point number-one of doing this was to solidify the support of Hispanics, most importantly in making sure they get out the vote, which is so important for him in putting together a winning electoral coalition. The second point that they [the Obama campaign] hoped was true was that it would not alienate, unduly alienate, any of the voters they’re trying to reach. The polling that just came out, and this is from Bloomberg, shows that something like sixty-four per cent of likely voters approved of Obama’s move. So that is a good sign. Now, they didn’t break it up by white college, white non-college, and so on. But the fact that “independents” in the poll supported it as well would lead me to infer that there’s unlikely to be overwhelming opposition among white working-class voters. That’s typically not the way it works. So, I think that that looks pretty good, but we’ll have to wait to see the numbers on this.

Is there anything Romney can do to reach Hispanic voters? We’ve heard him saying, off the record, that they’ve got to do something. Is there anything the G.O.P. can do about this, or are they stuck?

I think they are stuck and I think they know they’re stuck. Not that they have admitted defeat, but just that I don’t think there’s anything in particular they can do, because they are so boxed-in on issues that are of concern to Hispanic voters, especially issues concerned with immigration. They don’t have a lot of degrees of freedom to change Romney’s stance. Whenever I’ve seen his Hispanic outreach coördinator quoted, and people relating to that part of the campaign, their message is always, “Well yes, Hispanics have many concerns, but their chief concern is the economy.” The message for Hispanics, as far as I can figure out, is no different than the message for everybody else, and I think that they don’t, in fact, have a plan that could work on Hispanic-specific issues.

I think I heard you saying somewhere that if Obama wins eighty per cent of the minority vote, which seems possible, the minority vote is now so big that he could actually lose among white voters by a large margin and still come out on top. What’s the arithmetic there?

Ok, there’s a number of different ways to look at it. But just taking the scenario where twenty-eight per cent of voters are minorities and he gets eighty per cent of the (minority) vote Now, if that happens, he could lose white working-class voters by twenty-eight points, or something like that— pushing close to the level that congressional Democrats lost them in 2010 —and he can lose white college-graduate voters by something close to the nineteen points the Democrats lost them by in 2010. In other words, almost as bad a performance among both groups of white voters as in 2010, and he could still squeeze by. And that’s a lowball estimate—he’s doing much better than that right now among both these groups. In fact, he’s doing way better among white college-graduate voters. He’s almost running even with Mitt Romney.

And how’s he doing with the white working classes?

That continues to be his worst group in pretty much all the polls. Very rarely do you see him doing as well as he did in 2008 with this group. We’d expect some slippage. The question is how much slippage is he going to get? And so far, it’s not the worst. For example, here’s the latest Pew poll. Well, it looks like he’s basically losing by twenty-one or twenty-two points among white non-college voters. That sounds bad, and it is bad, and [the Obama campaign[ would love it if it was better. But the fact of the matter is that, especially given the state of the minority vote that we were just discussing, he can clearly live with that.

You said he can lose the white non-college vote by twenty-eight percentage points and still win?

Yes. He could, I think, if the minority vote is strong enough. But that’s not anything they [Obama’s campaign managers] want to see happen. And they’re obviously working very hard to try to get as many of these white non-college voters as they can.

What about the white vote overall—if you put the non-college with the college-educated together? What sort of target does he have to aim for there? (In 2008, Obama trailed John McCain by twelve points among white voters: fifty-five per cent to forty-three per cent)

Right, ten to twelve points is basically not a problem. He can live with that. I think Ron Brownstein (of the National Journal) always puts it at around thirty-nine per cent of the white vote he could live with. I could even see him under certain circumstances winning with thirty-eight of the white vote. But that’s, of course, including all the different flavors of white voters, both college and non-college.

So if the white vote splits sixty-forty—he could live with that?

Yeah, this is making it kind of close, but he could live with it. I mean, again, it’s not their desired scenario, but this is to illustrate the degrees of freedom they have given the state of the minority vote.

And among women? How’s the gender gap looking now?

It’s still out there. It really ballooned there for a while, maybe six weeks ago. It’s still quite substantial. And, of course, it’s not just all women that are equally good for Democrats: in particular, it’s single women and also more educated women.

Obviously, the Romney campaign, one of their big efforts is trying to close that gender gap, and leave behind some of the social issues they got wrapped up in during the primaries. Do you think they have any chance of doing that?

I don’t think there’s much. I mean, clearly, they’ve succeeded somewhat in closing the gap with Obama overall, but I would attribute that more to the Romney campaign getting its act together, no longer having to fend off the crazy Republican primary challengers, and, of course, most importantly, the faltering of the economy, or the perception of a faltering economy that’s appeared. So, Romney’s making progress and he’s running and he’s sticking to his message. He wants to reassure the people about social issues whom he thinks he can reach, but I think it’s less by taking positions than by not talking about them at all, and trying to say, you know, “Did I mention the economy is bad, and I can actually fix it and the guys in office can’t?” This is the simplest challenger message that there is.

You put out a paper in November of last year talking about demography versus economics in 2012. And that tension now seems to be shaping up as one of the most important factors, perhaps the most important, in the campaign.

That was the frame we put in our paper. If you went with the underlying changes in the electorate over the last four years—what put Obama in office in the first place—they are clearly on his side. All the changes we’ve talked about are continuing, and they advantage him overall in basically all the key states. What he doesn’t have on his side is even more obvious—the state of the economy, which, while it has improved, has improved at a relatively slow pace and is clearly the main point of vulnerability for him. So the question for him is whether he can leverage those demographic advantages and turn them into a victory in a situation that’s really quite difficult for the incumbent.

Just because the Democrats have the demographic wind at their back, doesn’t mean they’re going to win every election and doesn’t mean they’re immune to the crosswinds that typically affect any incumbent party elected for any reason. So, there’s no logical reason to think the Democrats would not be hurt, and hurt badly, by the state of the economy

One group that has emerged as an important part of the Obama base, which wasn’t in your original book, is the ”millennials”—young people, basically. The Obama campaign is making a big push to generate the same sort of enthusiasm he had in 2008. How do you think that’s working with young voters?

The age group we have data on is eighteen to twenty-nine, and you can tell two things basically. One is that he’s running better among that age group than any other age group, suggesting a continued leaning in his direction among these voters. The second thing is that the gap in his favor is not as large as it was in 2008. For example, in this Pew poll I was just mentioning, he had an eighteen-point lead. Now that sounds good. That is good, right? But thirty-four points, it’s not. So, I think they’re concerned about that.

GEOGRAPHY

Okay, let’s switch to geography. Earlier, I was thinking back to the original states you identified in 2002 as the states most likely to swing to the Democrats and comparing them to the electoral map of Jim Messina (Obama’s campaign manager) and his various ways to get to two hundred and seventy electoral votes. One of Messina’s paths is the western path: Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Iowa. In your book, you also had the West as a great opportunity for the Democrats. How’s that western strategy looking, and are the demographics still running in Obama’s favor?

Obama’s looking very good, generally, in the region, I’d say. New Mexico is looking very, very good for him. I think that’s always going be the easiest state of the three. Nevada, I would put next in terms of the likelihood of Obama carrying it. One thing that’s remarkable about Nevada is the rate of change that it’s experiencing demographically. The shift towards minority voters is just occurring with such stunning speed. I have some new data here that I’ve been working on with Bill Frey of Brookings and it looks like eye-popping data.

What we’ve got from our data is that between 2008 and 2012 [the minority eligible voter share] grew at a rate of roughly two percentage points a year: so an eight-percentage-point shift over the four-year period. And we’re winding up roughly today with thirty-nine per cent of eligible voters being minorities in Nevada. That’s not of the entire population. These are people who are citizens and eighteen and over. That’s huge, and so I think Nevada is very accessible for Obama.

Colorado is the most competitive of the three. The big question there is with the white voters. Obama did exceptionally well among white college-educated voters in Colorado, in 2008. I haven’t seen any data, and we don’t know the extent to which he’s able to repeat that, but one would infer that probably the gap in his favor is smaller because of how close the polls have been. They’ve been roughly even between Obama and Romney. But, here too, we see the same sort of demographic changes we’re talking about. This data I’ve been talking about that Bill Frey and I have been working on: it looks like over a four-year period, we might be looking at an increase of about three-and-a-half percentage points of minority eligible voters driven heavily by Hispanics, in fact almost entirely by Hispanics.

And what does that take the minority vote share up to Colorado?

According to our data, it should take it up to twenty-two per cent of eligible voters being minorities.

And what about Arizona?

The Democrats did lose it by eight points or so, in 2008: you wouldn’t expect that winning it would really be too plausible (for Obama). I wrote an article in The New Republic in which I tried to cite some of the data showing that it is, at least, possible. I’d say the odds are against Obama. But if there is any state he did not carry in 2008 that he might be able to carry in 2012, I think it would be Arizona. For example, if you look at the Hispanic vote in Arizona in 2008, it was only fifty-six to forty-three Obama, at least according to the exit polls. And obviously they [the Republicans] don’t have a local favorite running in Arizona in 2012, which would probably be a huge difference. So I think there’s a basis here. And then, when you add in the rate of demographic change there, which is huge, it just starts to sound like something that’s not completely crazy.

Another area you originally identified as a bright spot for the Democrats was the upper Midwest, which seems to be turning into a bit of a problem area for Obama now: Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin. How do you interpret what’s happening there?

I think these states will be competitive. The issue for Obama in these states has always been whether he can hold his losses among white working-class voters to a level that would make it possible for him to take them. Michigan, I’m not sure I believe that it’s really that accessible for the Republicans. There have been some outlier polls recently. Rasmussen actually had Obama ahead by eight points, which, knowing Rasmussen, is pretty impressive. The Pollster.com estimate is a five-point lead. And I think if you look at Nate Silvers’s sort of souped-up model of this stuff, I think he still has Obama as a very heavy favorite.

And I think the same thing could be said of Wisconsin. The polls are closer there, but if you look at the underlying situation in Wisconsin, it’s not so clear that it’s really that much in play. It’s in play, but it’s not quite as close as the Republicans want to put it. The pollsters asked people in the recall electorate who they would vote for in the Presidential election, and Obama won by seven points. The recall electorate was skewed demographically towards the Republicans. You would think that was kind of a weird result, indicating that the anti-Walker recall sentiment doesn’t necessarily play into, you know, voting for Romney.

So, you don’t think it’s too alarming what’s happening in that region, from Obama’s perspective?

Well, I think it’s alarming in the sense that yes, there’s a narrowing, and we pretty much know what to attribute it to: Romney getting his act together and just running a more tight, disciplined campaign, focussing on one issue and one issue only and that’s the economy. It’s not a state secret that the road to glory if you’re a Republican in that area is to build on that issue, and by building on that issue, try to jack up your margins among white non-college voters.

But if you are Republican, isn’t that one place you can fight back against the demographic trends, potentially anyway? If you had to pick one area of the country, wouldn’t that be it?

That’s where some of the opportunities are. I think the most obvious places to push back against the Obama coalition are in the South: Florida and North Carolina. At this point, [it’s] more probable than not that [the G.O.P. will] take those two states. Now, you could argue that that’s just the foundation: that doesn’t put them over the line. Some of their best opportunities (for gains) will occur in some states in the Midwest. The most important, by far, is Ohio, because if Obama takes Ohio the arithmetic just becomes so difficult for the Republicans. Whereas, Obama can lose Ohio and he can make up all those electoral votes, and then some, by carrying Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico.

How do you read the Ohio situation? Obama’s numbers appear to be holding up a bit better than in some of the other Midwestern states.

The economy is doing better there, that’s right, and that should help [him]. There’s been a lot of academic tussle over whether a particular state’s economy matters to a Presidential vote. I think the upshot of that is, yeah, it matters some. But the national economic situation still looms quite large in the calculus of voters in those states.

So what’s your take on Obama’s chances in Ohio at this moment?

It’s looking like a true tossup at this point. The polls we’ve seen are roughly tied. The trend has been a little bit towards Romney, as we would expect based on the way things have gone in terms of the economy and the Romney campaign consolidating itself. The minority vote isn’t nearly as large there. African-Americans support [Obama] at really high levels, but the minority population is not as large as in most states—and also, as far as we can figure out, it isn’t really growing. It’s one of the states where there’s been the least amount demographic change.

In 2008, Obama basically split the white college graduate vote, so that’s pretty important, to keep that somewhere near that level. But the white working class he lost by ten points. And the white working class is exceptionally large there, so I think the white non-college voters are really the key. Minus ten points is something he can live with among that group. But if it’s minus twenty, minus twenty five—the farther down it goes, the worse his chances become, and I think that’s really the key to the whole thing.

The Obama campaign has been pushing the auto bailout as a way of boosting support among working-class and middle-class voters, not just in Michigan but also in other Midwestern states, like Ohio. Is that a reasonable argument do you think?

I think it’s a reasonable argument. It should have effects on the adjoining states to Michigan, and it may be helping him now. But against the overall economy, it’s not enough in and of itself. It doesn’t automatically deliver any state for Obama, far from it.

Last one on geography: the South: Florida and North Carolina…

I think, realistically, both North Carolina and Florida are tough carries for the Obama campaign. North Carolina in particular seems pretty unlikely at this point, but I could be wrong about that, obviously. Florida, also at this point, I think you’d have to say Romney is favored in the state.

Why is Florida so hard for Obama? Gore virtually took it in 2000, and there must have been demographic changes favoring the Democrats since then?

And there’s more demographic change coming up. Florida, according to our data, has actually been accelerating its shift toward a minority voter electorate by about a percentage point a year from 2008 to 2012, which brings Florida to about thirty-five per cent minority eligible voters. So that’s good for Obama. And the growth in the minority population has been driven not by Cuban Hispanics but by non-Cuban Hispanics. That helps him.

But then if you look at the other data in Florida outside of the big metro areas in the south [Obama] doesn’t typically do well with even with white college voters. The typical M.O. for the Obama coalition is to not do that well among white working-class voters but to have a much more respectable performance among white college-educated voters. And according to our data, I think he lost white college voters by almost as much as he lost (non-college whites). Let’s see here yeah, white college graduates, he was minus thirteen in Florida in 2008; white working class, minus seventeen. There’s not that much difference.

And the local economy is doing quite badly.

The economy is quite bad, and it hasn’t been improving that fast, so that gives the Romney campaign a lot to work with. In terms of geography, the I-4 corridors are where the real battle will be fought. Obama managed to carry the I-4 corridor in 2008. It seems quite plausible that he won’t carry the I-4 corridor in 2012.

Do you think Romney selecting Marco Rubio as his running mate would have much impact? I mean, he’s not an I-4 corridor guy, is he?

He’s not really. There’s always been some debate about how much a Rubio selection would help Romney, even in Florida. I guess you’ve got to believe that, at the margin, he would be somewhat helpful, but not determinative necessarily. But they may be thinking, since they’ve been running pretty well in Florida, they have a pretty good chance of taking the state anyway. There’s not as much of a compelling need to select Rubio, and his attraction to non-Cuban Hispanics is clearly exaggerated in any state but Florida—it may even be exaggerated in Florida.

PUBLIC OPINION/CAMPAIGNING

One of the other interesting things you’ve done over the years, Ruy, is the stuff on public attitudes to major policy issues. You’ve argued that there’s a “progressive center.” Is that progressive center still intact?

I think the potential progressive center is certainly still there. First of all, let’s talk about the ideology thing. The number of [self-defined] “conservatives” really hasn’t changed very much. There was some decline in “moderates” there for a while and some slight increase in “liberals.” But the American ideological spectrum doesn’t really change much over time in that sort of three-point way.

And if you look closely at those categories, it’s always been the case that “moderates” are not just people who are totally in the middle, but actually tend to lean toward what you might call a progressive view on policy attitudes. Moderates reveal this by their voting preferences, which are typically substantially more Democratic than Republican. So I’ve always thought it strange to say, because “conservatives” are bigger than “liberals,” it’s a center-right country. When you actually put together “moderates and “liberals” you have a substantial majority. And “moderates” are more plausibly thought of as “liberals” than “conservatives.”

If you look at policy attitudes, a lot of the attitudes people have about what they’d like to see the government do, what they’d like to see accomplished, and even the spending they’d like to see done in certain areas, really hasn’t changed that much. There’s still a lot of appetite for positive actions by the government for what you might think of as progressive change, that the government needs to do more they just don’t really believe the government is capable of doing it.

Can you give me a couple of examples?

Here’s an example. It’s just one data point, but there are many others. We did this poll at the Center for American Progress on what Americans want from government, as part of this project that we call “Doing What Works”—it’s basically how to make the government function better and more efficiently. This was done, I think, about the middle of 2010. Not a great time for Democrats: the backlash was gathering. The economy was still in the toilet and things had really swung against the Democrats.

At this point, we found that people said on the one hand that they didn’t have much confidence in the federal government’s ability to solve problems. Only thirty-three per cent said they had a lot or even some confidence in the federal government’s ability to solve problems, the lowest that had ever been measured since the questions started being asked in the nineteen-nineties. Fifty-seven per cent said the government is doing things better left to business and individuals. At the same time, if you asked them if they wanted federal government to have more involvement in several areas, you got sixty-one per cent saying we need more government involvement in developing clean energy; sixty per cent in improving public schools; sixty per cent in making college more affordable; fifty-seven per cent in reducing poverty; fifty-one per cent in ensuring access to affordable health care—this was after the health-care reform bill passed. So that’s pretty indicative.