John Cassidy's Blog, page 96

June 4, 2012

Reagan, Bush, and Obama: We Are All Still Keynesians

The reaction to the May employment report has been depressingly predictable: Republicans have been gleefully proclaiming that President Obama’s fiscal stimulus didn’t work. Many people who commented on my post about the political impact of the job figures parroted the same line, arguing that the lackluster economy demonstrates Keynesianism is a bust.

Having spent much of the past three years reading and writing about this subject, I wonder whether it is even worth engaging with these arguments. The aversion to government spending, and government activity generally, which animates many Americans isn’t actually based on economics, or logic: it is an emotionally driven belief system, founded upon a cockeyed view of American history and buttressed by a variety of right-wing shibboleths.

In the real world that rarely intrudes upon conservative economists and voters, both parties (and all Presidents) are Keynesians. Whenever the economy falters and private-sector spending declines, they use the tax-and-spending system to inject more demand into the economy. In 1981, Ronald Reagan did precisely this, slashing taxes and increasing defense spending. Between 2001 and 2003, George W. Bush followed the same script, introducing three sets of tax cuts and starting two wars. In February, 2009, Barack Obama introduced his stimulus. The real policy debate isn’t about Keynesianism versus the free market, it is about magnitudes and techniques: How much stimulus is necessary? And how should it be divided between government spending and tax cuts?

On both questions, Obama took the middle ground. His $800 billion stimulus program was smaller than many Keynesians, such as Christine Romer and Paul Krugman, wanted. (Romer reportedly pushed first for a $1.8 trillion package, then for $1.2 trillion.) Concentrated over a three-year period, it amounted to 1.1 per cent of G.D.P. in 2009, 2.4 per cent of G.D.P. in 2010, and 1.2 per cent of G.D.P. in 2011. So far, some $750 billion in stimulus money has been paid out: about $300 billion went to tax breaks for individuals and firms; roughly $235 billion was dispersed in the form of government contracts, grants, and loans; and another $225 billion was spent on entitlements—unemployment benefits, Medicaid, food stamps, and so on.

And what impact did the stimulus have? Without rehashing the entire debate—we’ve got another five months for that—here are three things to keep in mind.

1. It gave a much-needed boost to spending and growth. A simple timeline tells much of the story. In the first quarter of 2009, G.D.P. fell at an annual rate of 6.7 per cent—a depression-style slump. During the rest of the year, as the first stimulus funds were distributed, the economy rebounded. In the third and fourth quarters of 2009, G.D.P. expanded at an annual rate of about 2.7 per cent. In 2010, when the stimulus was at its height, the growth rate picked up to three per cent.

Of course, the stimulus wasn’t wasn’t big enough to bring down the unemployment rate very far, and it wasn’t the only thing that got the recovery started. The Bush Administration’s bailout of the banking industry and the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending programs helped stabilize the financial markets, an essential precondition for a turnaround. The Obama Administration’s bailout of General Motors and Chrysler rescued the auto industry, which is still by far the biggest manufacturing sector in the country.

But the stimulus definitely helped, evidenced by the fact that when it began to wind down the recovery faltered. In 2010, the stimulus injected about $350 billion into the economy in the form of spending and tax cuts. In 2011, the stimulus was cut in half—to roughly $175 billion—and G.D.P. rose by just 1.7 per cent. (Some of the dropoff in stimulus funds was offset by other legislation: in December, 2010, in exchange for an extension of the Bush tax cuts, congressional Republicans agreed to extend unemployment benefits and payroll tax cuts.)

2. The rise in federal spending under Obama was pretty modest. If you listened to the Republicans, you would think he had massively expanded the size of the U.S. government. That simply isn’t true—a point that can be illustrated in several ways.

One is to look at the path of federal spending as recorded by the Office of Management and Budget. In fiscal 2008, total federal outlays came to $2.7 trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 2012, according to the O.M.B., they will be $3.2 billion. That is a rise of about 18.5 per cent over four years, an annual increase of about 4.3 per cent. How does that rate of growth stack up with the record of previous Presidents? Well, it means Obama has expanded federal spending a bit faster than President Clinton. But Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush both increased spending at considerably higher rates. (Thanks to Rex Nutting, a columnist at MarketWatch, for drawing my attention to the historic data.)

So the figures show Obama wasn’t much of a spendthrift. And he wasn’t even responsible for most of the increase in federal spending that happened on his watch: it came in the form of higher outlays for mandatory programs, such as Social Security, other entitlements, and interest on the national debt. Over the past four years, discretionary spending—the bit of the federal budget that policymakers can control—has increased by just $106 billion, or a little more than ten per cent. That’s an annual rate of increase of about 2.4 per cent.

If you delve into into the O.M.B. Web site, you find other rarely discussed figures. Take spending on infrastructure projects—roads, railways, bridges, and other big-ticket projects that are often labelled as Keynesian. In 2008, the federal government spent $154 billion on non-defense capital projects. Here are the figures for the past four years: 2009, $178 billion; 2010, $186 billion; 2011, $178 billion; 2012, $191 billion. If you average out these numbers, you will find that under Obama federal spending on “Keynesian” capital projects has risen by less than $30 billion a year. In a $15 trillion economy, that is a rounding error.

3. Paul Krugman is right. To some extent, we already have a Republican economy. With the flow of stimulus money having all but dried up, and with continuing budget cutbacks at the state and local levels, government spending on many goods and services—the government spending that directly impacts G.D.P.—is falling.

You don’t believe it? Take a look at Table 1 in the Commerce Department’s latest report on G.D.P., and focus upon the section labelled “Government consumption expenditures and gross investment.” In 2011, you will notice, these expenditures declined at an annual rate of 2.1 per cent. In the first three months of this year, the rate of decline accelerated—to 3.9 per cent. The cutbacks have extended to all the major areas of government. Federal non-defense spending fell at an annual rate of 0.8 per cent in the first quarter; federal defense spending declined at an annual rate of 8.3 per cent, a shocking figure; state and local spending fell at a rate of 2.5 per cent.

It is a central tenet of Keynesian economics that when the government sector cuts back its expenditures in an economy with slack resources, worried households, and cautious business enterprises, output and growth will stall. That, of course, is precisely what has happened. In a saner world, we would be talking about what should be done right now, rather than after November, to rectify the situation.

Photograph by Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

June 1, 2012

Jobs Slowdown Could Cost Obama the Election

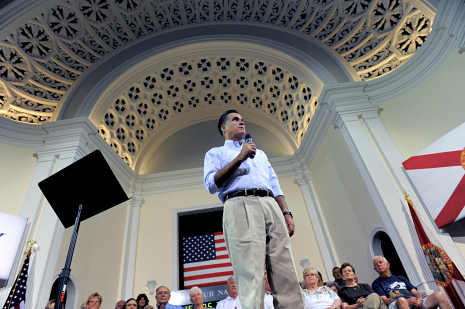

I hate to ruin your weekend, but let’s be honest: Mitt Romney now has a good chance of being the next President.

How good is good? Your guess is worth as much as mine, but we both know that the likelihood of a Romney victory went up considerably this morning with the release of a shockingly bad jobs report. According to Intrade, an online betting site, it jumped six per cent, and is now more than forty per cent. Obama is still the favorite, but the gap is narrowing.

Yes, it’s just one month of job figures, and things could look better a month from today. But, from President Obama’s perspective, this was a truly horrible jobs report. Nobody, and I mean nobody, was expecting the May figure for growth in payrolls to come in as low as it did: sixty-nine thousand. And nobody was expecting the April figure—at a hundred and fifteen thousand already pretty anemic—to be slashed by nearly fifty thousand, to seventy-seven thousand.

With the May unemployment rate ticking up from 8.1 per cent to 8.2 per cent, the White House’s misery was virtually complete. Talk of a new recession is overblown, but the economy has clearly stalled at a very awkward moment for Obama. Between January and March, it created two hundred and twenty-six thousand jobs a month, according to the Labor Department’s payroll survey. In April and May, this figure fell by two thirds—to seventy-three thousand.

No wonder the Republicans are cock-a-hoop. “These jobs numbers are pathetic,” Eric Cantor, the House Majority Leader, said on CNBC this morning. “And I think it cries out now for us to try something new

. The policies coming out of the Administration have not worked.”

That is the Romney argument, of course. “This week has seen a cascade of one bad piece of economic news after another,” Romney said in a statement. “Slowing GDP growth, plunging consumer confidence, an increase in unemployment claims, and now another dismal jobs report all stand as a harsh indictment of the President’s handling of the economy.”

From an economic point of view, this is misleading. Obama’s policies helped prevent a Great Depression. Since the spring of 2010, payrolls have risen by more than four million. If the do-nothing Republicans in Congress had passed the Administration’s American Jobs Act, which contained more financial help for cash-strapped states that are still laying off teachers and other employees, many more Americans would be working.

In short, the Republicans are full of it. But politically speaking, their argument is a potent one—and Obama’s campaign knows it. As I’ve pointed out before, when an incumbent seeks reëlection, the key to his fate is the trend. In the first three months of the year, Obama could make the case that things were finally turning around, and he deserved another term. His approval ratings improved, and Romney’s argument that he was the only one who could fix the economy looked silly. Now Romney is back in the race.

It isn’t as if the Republican nominee-elect has a credible solution to the jobs crisis. He doesn’t. His fifty-nine point economic plan, which combines drill-drill-drill with tax reform, the repeal of Obamacare, and long-term fiscal retrenchment, would have little or no impact on the unemployment rate. And if he gave into the Republican right and started slashing federal spending straight away, he could well bring on another recession. But when things are bad, challengers are held to a lower standard than incumbents. The “time for a change” argument often resonates more strongly with voters than the incumbent’s critique of his opponent’s plans.

That is the dynamic that leads to changes of government. It isn’t fully in place this year, but one or two more employment reports like this one and it could well be. “Absolutely nothing good to be said about today’s #jobs numbers,” Steve Rattner, Obama’s former auto czar, tweeted this morning.

That’s not strictly true. In a blog post he put up about an hour after the job figures, Alan Krueger, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, pointed to the Labor Department’s survey of households, which showed employment rising by four hundred and twenty-two thousand last month—more than six times as much as the figure from the payroll survey.

Economists don’t pay as much attention to the household-survey job figures, because they bounce around a lot and the sample is smaller. But like the payroll number, it’s an official measure of employment, and it might even be accurate. We simply don’t know. (The payroll survey should also come with a health warning attached. Its margin of error is a hundred thousand—meaning the actual jobs figure could be anywhere from negative thirty-one thousand to a hundred and sixty-nine thousand.)

The household survey also showed that more people are looking for jobs, which is usually a sign of an economy recovering. Last month, the labor force increased by six hundred and forty-two thousand, and the participation rate—the proportion of able-bodied adults who are working or looking for work—rose from 63.6 per cent to 63.8 per cent. Is this finally some good news for Obama? Politically, it isn’t. Some of the people who rejoined the labor force last month couldn’t find jobs. Hence, the number of people officially recorded as out-of-work rose by two hundred and twenty thousand, and this caused the headline unemployment rate to tick up by a tenth of a per cent.

In short, the employment report is sticking it to Obama from both sides. The payroll survey shows stagnant job growth, the stock market tumbles, and all hell breaks loose. The household survey shows many more jobs being created but a rising unemployment rate, and that is what grabs the headlines.

Happy days in Beantown!

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

May 31, 2012

Obama and the Bush Legacy: A Scorecard

With two George Bushes and their wives visiting the White House today for the unveiling of George W.’s official portrait, how much of the Bush legacy remains in place? The election of 2008 was a classic “time for a change” contest, in which Americans picked a fresh-faced young senator to replace an increasingly haggard and unpopular President. Three and a half years later, what’s different?

Some things are; some aren’t. Here is a quick (and far from definitive) scorecard. But first, a warning: this isn’t an exercise in judging Obama. In some areas, such as dealing with the Supreme Court, he was powerless to undo Bush’s handiwork. In other areas, such as Afghanistan, he set out to complete Bush’s agenda rather than overturn it. But it’s always interesting to compare Presidencies and to try and figure out what, if anything, they leave behind that’s lasting. So here goes:

1. Iraq: To a large extent, it was Obama’s anti-war stance that won him the Democratic nomination. A month after taking office, he said the combat mission would end by August 31, 2010, with a transitional force of up to fifty thousand soldiers remaining in Iraq until the end of 2011 at the latest. This timetable was carried out successfully: the last U.S. combat brigades rolled into Kuwait in August, 2010, and the final members of the transitional force left on December 18th of last year, following a breakdown in negotiations about maintaining a U.S. presence.

Today, there are a few hundred U.S. military personnel left in Iraq, operating out of the vast U.S. embassy in Baghdad. The C.I.A. also retains a substantial presence, and there are thousands of security contractors working for the State Department in Baghdad and other cities. But for all intents and purposes, the U.S. military occupation is over.

Score one for Obama.

2. Afghanistan: Obama’s anti-war reputation was always a bit misleading. In the summer of 2008, he vowed to step up military operations in Afghanistan, calling it “the real center for terrorist activity that we have to deal with and deal with aggressively.” At the time, there were about thirty thousand U.S. troops in the country. Today, there are about ninety thousand, roughly a quarter of whom are due to leave by the end of the summer. Obama has vowed to end the occupation by the end of 2014, and the results of his “surge” are hotly debated.

In his recent televised speech from Kabul, Obama said the U.S “broke the Taliban’s momentum” and has “built strong Afghan security forces.” But many independent analysts, such as Anthony Cordesman, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, believe the military strategy has failed. Meanwhile, the U.S. death toll continues to mount. At the start of 2009, when Obama took office, about six hundred and twenty-five U.S. military personnel had died as a result of the invasion of Afghanistan, according to the Associated Press. Today, that number stands at eighteen hundred and fifty-seven.

Score one for the Bush legacy.

3. Tax cuts: In a series of bills passed between 2001 and 2003, George W. slashed the rate of taxation on ordinary income, dividends, and capital gains, giving a huge handout to high-income households. As a candidate, Obama vowed to repeal the cuts for households with incomes of more than two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. It didn’t happen.

Following the financial crisis of 2008, the Administration was reluctant to raise taxes on anybody for fear of making the economy worse. During the 2010 mid-term elections, Obama returned to a theme of making the tax system fairer. But after the Republicans swept to victory, he agreed to extend the Bush tax cuts for two more years in exchange for Republicans agreeing to extend unemployment benefits and cut the payroll tax. The tax cuts are now due to expire at the end of this year, but it’s not clear whether that will happen.

Score another for the Bush legacy.

4. Wall Street: In a March, 2008, speech at Cooper Union, Obama delivered a robust defense of financial oversight, depicting the deregulation of the Clinton and Bush years as a “corrupt bargain in which campaign money all too often shaped policy.” In July, 2010, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which set up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and beefed up the powers of other regulators, including the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department.

The reforms didn’t go nearly as far as many commentators, myself included, would have preferred. With the help of congressional Republicans, financial lobbyists managed to water down some of the bill’s provisions, such as the Volcker Rule and rules regarding the trading of complex derivatives. But the bill still amounted to the most significant piece of regulation in decades, and, together with the imposition of tougher capital requirements for big banks, it has changed how Wall Street operates—to some extent, anyway.

Score one for Obama.

5. Health care: George W.’s approach to health-care reform, such as it was, involved introducing a costly prescription-drug program to Medicare and encouraging people to set up tax-free Medical Savings Accounts to pay for future health-care costs. For people who didn’t receive health insurance from their employers and who couldn’t afford to purchase it on the open market, he proposed (but didn’t introduce) tax breaks of up to three thousand dollars. For his reform bill, Obama, after initially supporting a public option, also chose to work with the existing system of private insurance. But in mandating that individuals buy coverage, in setting up health-insurance exchanges, and in establishing a system of big and costly subsidies for low- and middle-income families, he went far, far beyond Bush’s modest agenda.

Score another one for Obama.

6. The Supreme Court: George W.’s most lasting legacy may well have been his creation of a conservative majority on the high court under Chief Justice John Roberts. Obama, not through any fault of his own, has been unable to alter the court’s balance. (His two moderate-liberal appointees, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, both replaced moderate justices.)

Sometime in the next few weeks, the Court will rule on the President’s signature policy initiative: health-care reform. If it throws out all or part of Obamacare, the power of the Bush legacy will be clear to all. Even if the health-care bill, or most of it, survives the coming decision, the Court is set to play a key role in the election. Its controversial 2010 ruling in the Citizens United case has set off a fund-raising free-for-all, which, so far, is benefitting Mitt Romney more than Obama. If the President were to lose in November, many of his supporters would blame the Court.

Score another for the Bush legacy.

7. Gay rights: In ending the military’s policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and, more recently, expressing his personal support for gay marriage, Obama has definitely broken with the Bush legacy. Back in 2004, George W. came out in favor of a constitutional amendment restricting marriage to a man and a woman. Last year, one of his daughters, Barbara, who lives in New York, taped a video expressing support for legalizing gay marriage. Neither of her parents commented on the video.

Score one for Obama.

8. Workers’ rights: After eight years of anti-union policies under George W., Obama vowed to change course. He expressed support for a “card check” bill, which would have allowed workers to form a union once they had collected the signatures of a majority of their colleagues. Despite the President’s support, the bill never made it through Congress. However, Obama did make a number of administrative changes that favored unions, such as strengthening regulations on the distribution of federal contracts and appointing sympathetic people to the National Labor Relations Board, which investigates unfair labor practices.

Last year, the N.L.R.B. infuriated Republicans by objecting to Boeing’s decision to establish a production line for the 787 Dreamliner, its next big plane, in non-union South Carolina. (The case was later settled.) This sort of stuff doesn’t grab many headlines. But the hysterical attacks on the N.L.R.B. by business interests and congressional Republicans indicate that it is important.

Score another for Obama.

9. The war on terror: In publicly disavowing the use of torture, including waterboarding and other “enhanced” interrogation techniques, Obama made a big break with the Bush Administration. He also made some significant reforms to the military-tribunal process. But he didn’t close Guantánamo Bay, and he abandoned efforts to bring senior Al Qaeda members to trial in the United States. Meanwhile, he expanded covert anti-terrorism operations, including the use of drones to carry out targeted assassinations in foreign countries.

As a remarkable story in the Times about the drone campaign made clear, and as my colleague Amy Davidson has already commented upon, Obama regularly oversees “Terror Tuesday” meetings at which he authorizes (or refuses to authorize) individual strikes in places like Yemen and Somalia. The war on terror is alive and well, and so is the expansion of Presidential power that George W. championed.

Score one for the Bush legacy.

10. The environment: When Obama came to power, environmentalists had great hopes. Today, many of them are disappointed. The President botched efforts to push cap-and-trade legislation through Congress, his Environmental Protection Agency abandoned efforts to strengthen anti-smog regulations, and his Administration approved more offshore drilling. Last year, some Obama supporters were so furious at his record that they compared him to George W. That was unfair. The Obama Administration has expanded land and water conservation programs; it has provided generous subsides to alternative energy producers; it has toughened up emissions standards for cars and factories; and it has put the Keystone XL pipeline on hold. But the candidate who in 2008 described global warming as an existential threat has yet to come up with a credible strategy, domestically or internationally, to reduce carbon emissions in a significant way.

Score another one for the Bush legacy.

By my tally, that’s 5-5: Obama has consigned some of the Bush era to history, but by no means all of it. Since his party was in control of Congress for just two years, and he had an economic crisis to deal with, that perhaps isn’t too surprising. But the people who’d expected him to fulfill all his promise still have plenty of reason to be disappointed.

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/GettyImages.

May 30, 2012

“This Is the President Calling for Governor Romney”

Barack Obama called Mitt Romney Wednesday morning to congratulate him on assembling enough delegates to secure the Republican nomination. “President Obama said that he looked forward to an important and healthy debate about America’s future, and wished Governor Romney and his family well throughout the upcoming campaign,” Ben LaBolt, an Obama campaign spokesman, said. Aides to Romney confirmed the conversation had taken place, and said it was cordial. But how might it have gone? Perhaps something like this:

An upscale hotel suite out West. The phone rings, and one of Mitt Romney’s aides picks it up.

WOMAN’S VOICE: Hello, this is the White House operator. Is that Governor Romney’s room? I have the President on the line.

ROMNEY MINION: Sure you do. Who is this—“The Colbert Report” or Howard Stern?

WHITE HOUSE OPERATOR: I’m serious, sir. This is the President calling for Governor Romney.

ROMNEY MINION: Hold on a minute, madam. Governor, there’s a lady here who says she’s the White House operator and she has President Obama on the line. [Muffled voices.] O.K. madam. I’m sorry for making a joke. Governor Romney will be right with you.

THE MITTSTER: Good morning, this is Mitt Romney. I’d be delighted to talk with the President. Please put him through.

WHITE HOUSE OPERATOR: Thank you, Governor. The President will be right with you.

THE POTUS: Good morning, Governor. I just wanted to say congratulations on wrapping up the nomination. Having slugged it out with Hillary four years ago, I think I know something of what you’ve been through. Michelle and I also wanted to pass on our best wishes to you and Ann for the rest of the campaign. Obviously, it’s going to be a long and hard-fought battle, but I hope we can have an honest and good-natured debate about what’s best for the country. The American people expect us to maintain a certain level of civility.

THE MITTSTER: Thank you. Mr. President. And all best wishes to you and your family, too. Setting politics aside, Ann and I have greatly admired how you, Michelle, and the girls have conducted yourselves over the past four years. I also echo your sentiments about keeping up the tone. The next time I refer to you as a radical former community organizer leading the country in a direction fundamentally alien to its values, or as a nice guy totally out of his depth with no idea how to fix the economy, I can assure you it won’t be personal.

THE POTUS: That’s very amusing, Mitt. It’s good to have a sense of humor. Maybe you should show it more often—no, don’t do that, it might help you in the polls. Anyway, I hear what you say. Next time I call you a cold-hearted vulture capitalist who has the blood of tens of thousands of patriotic, God-fearing American workers on his hands, please don’t take that personally, either. And don’t believe that stuff in this week’s New York magazine about my campaign trying to depict you as a right-wing dinosaur from the nineteen-fifties who’s going to ban abortion, birth control, and reality TV. That’s just Axe and the boys getting a little overexcited.

THE MITTSTER: Of course, Mr. President. I understand: politics ain’t beanbag. My guys up in Boston will be taking a few shots, too, but I’ve told them to stay away from Jeremiah Wright, the dog-eating, and the birthers. There’s some stuff that’s off limits, even if my new pal Donald Trump hasn’t got the message. Not quite sure what to do about him.

THE POTUS: I feel your pain, Mitt. I do. That’s one thing I don’t have to worry about this year: rich supporters making asses of themselves. Outside of Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and Omaha, Nebraska, I don’t have any. They are all sending checks to you—or to Karl Rove’s Super PAC. What was that figure I heard this morning? By the election, you and your allies will have spent $1.5 billion? That’s a lot of money, Mitt, even for somebody in private equity.

THE MITTSTER: O.K., O.K., Mr. President. Let’s leave Bain Capital out of this, at least for today. Wasn’t it Tony James of the Blackstone Group that you had dinner with in New York the other week? As I said on Fox News yesterday, the American people don’t resent success. They admire it.

THE POTUS: We’ll see about that, Mitt. I’ve got to go now—Joe Biden’s got another bright idea he wants to share with me. I’ll catch up with you in September at the debates. How about we do half a dozen of them in prime time, head-to-head, no interlocutors? Not exactly Lincoln-Douglas, but something similar. Folks will love it, and imagine how mad it will make Newt.

THE MITTSTER: Nice try, Mr. President, nice try. Now I know why you really called. I have to go, too—yet another fund-raising lunch, then a private meeting with Condi Rice, who may or may not be on my veep short list. One last thing, Mr. President: If I pick Condi, will you try and trump me with Hillary?

THE POTUS: Atta-boy, Mitt. You’re getting the hang of this game. See you out there on the stump. And by the way, twenty dollars says LeBron takes down the Celtics in five.

THE MITTSTER: Mr. President, you’re on. As a good Mormon, you know I don’t gamble. But let’s call it a friendly wager, with the winnings going to charity. Have a good day.

Click.

Photograph by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

May 29, 2012

Obama and the Economy: Crunch Time

A quick question: Is Barack Obama running for reëlection on the basis of a decent, half-decent, or poor economy? Given the ups and downs of the last few months, the question is surprisingly difficult to answer. In the next few weeks, we will get important news on several economic fronts. And what we learn will largely determine the shape of the campaign.

Here are three things to keep your eye on: the job figures, Europe, and the Federal Reserve. Since the start of the year, all have been behaving unpredictably. The unemployment rate fell sharply for a few months, and then, just when the White House was hoping that the recovery was finally taking off, it stalled. Europe finally seemed to be getting things together—then Greece voted against austerity, and Spain developed the wobblies. The Fed appeared to have given up on doing anything more to stimulate the economy, only for hints to emerge that it might still act.

Sadly for the Obama administration, there isn’t much it can do to gee things up. With Congress deadlocked, tax and spending policies won’t change before the election; even a mini-stimulus is out of the question. Europe follows its own path, and so does the Fed. The President and his advisers, pretty much like the rest of us, are reduced to a watching brief.

This week’s big news will come on Friday morning, when the Labor Department releases the May job numbers. Wall Street is expecting the payroll figure to come in at about a hundred and fifty thousand—that’s the number of new jobs created—and the unemployment rate to remain steady at 8.1 per cent. A surprise in either direction is perfectly possible. April’s figure of a hundred and fifteen thousand was a big shock on the downside. Another figure that low would cause dismay in the White House and (thinly disguised) jubilation at Romney HQ.

For what it’s worth—probably not very much—I think the payroll figure might well come in a bit higher than expected, and I also anticipate that April’s figures will be revised upward. (Upward revisions have been the pattern recently.) A big reason the numbers have bounced around so much lately is that the warm winter weather played havoc with the Labor Department’s statistical efforts to smooth out seasonal variations. With winter now receding into memory, the figures should be cleaner and more reliable.

A decent figure for job growth—close to two hundred thousand, say—would calm some nerves in the Obama campaign. But the payroll figure is only part of the story. Equally important from a political perspective is what happens to the unemployment rate, which is defined as the percentage of people who are actively seeking jobs but can’t find them. In recent months, even as job growth has slowed, the unemployment rate has continued to edge down, largely because so many Americans have stopped looking for jobs and dropped out of the labor force. In April, the proportion of the able-bodied adult population that is working or looking for work, a figure known as the “participation rate,” dropped to a thirty-year low of 63.6 per cent.

So far, the participation rate has been Obama’s friend—its decline has helped bring down the unemployment rate. But will this continue? If, over the coming months, more Americans return to the labor force and seek work, the unemployment rate could start edging up even as job growth picks up a bit. Of course, the Romney campaign would seize upon any such development.

Once the job figures are out of the way, attention will switch back to Europe and to Greece, which will hold a second election on June 17th. With the pro-euro parties now leading in the polls, the chances of Greece being ejected from the currency zone appear to be diminishing. But another potential flash point has emerged in Spain, where a full-scale banking crisis is developing, and the government has just seen its debt rating cut another notch.

Neither problem—Greece nor Spain—is beyond the capacity of the European authorities to deal with. But the way things work over there is that nothing gets done until there is an acute crisis. And a summer of European crises is just what the White House could do without. While the direct impact on most American households and firms would be small, the fallout in the U.S. financial markets could be considerable, and this, in turn, could damage consumer sentiment and political sentiment.

The latest consumer-confidence numbers are all over the place. Last week, a survey from the University of Michigan showed the figure at its highest level since 2007. Today, another survey, from the Conference Board, showed it falling for a third straight month. As I said, there are a lot of crosscurrents. But the over-all picture is of an economy still stumbling along with modest growth. To go back to the question I posed at the top, it’s half-decent.

That brings us to the Fed, which holds a key two-day meeting on June 19th and 20th. For the past year, or so, Ben Bernanke (the Fed chairman) and his colleagues have been in a holding pattern. Short-term interest rates remain very low, but the Fed has largely suspended its other efforts to boost activity, such as buying large quantities of bonds—so-called “quantitative easing.” Many economists believe it’s now too late for the Fed to do anything that would make much difference before the election. I’m not sure I agree.

While the central bank would face a tough task in seeking to boost job growth and corporate investment, it certainly has the ability to light a fire under the financial markets, particularly the stock market. If Bernanke were to announce another big round of quantitative easing, coupling it with a statement that the Fed would use whatever tools were necessary to prevent the economic recovery from slipping any further, the Dow and the Nasdaq would surely shoot up. A rising stock market wouldn’t solve the country’s problems, but it would cheer up tens of millions of Americans who have been anxiously watching their 401(k)s. From a political perspective, this could be pretty important.

What are the chances of the Fed acting in such a manner? Not very high, perhaps. But another bad set of job figures, a blowup in Europe, or a combination of the two, could change things pretty quickly. It is going to be an interesting month.

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

May 25, 2012

The Obama Wobble: Real or Media Invention?

As Barack Obama prepares for a holiday weekend with his family, the campaign hack pack has a message for him: Get your act together, buddy, before it’s too late! Just a few weeks ago, the conventional wisdom was that the President was virtually unbeatable: game over. Now many media savants and political insiders have spotted an alarming wobble in his victory march back to the Oval Office. “Obama Stumbles Out of Gate,” blared a Friday morning headline on Politico, home base for political junkies of all stripes.

Mike Allen and Jim VandeHei wrote that just three weeks after the President formally kicked off his reëlection campaign,

Obama, not Mitt Romney, is the one with the muddled message—and the one who often comes across as baldly political. Obama, not Romney, is the one facing blowback from his own party on the central issue of the campaign so far—Romney’s history with Bain Capital. And most remarkably, Obama, not Romney, is the one falling behind in fundraising. To top it off, Vice President Joe Biden has looked more like a distraction this month than the potent working-class weapon Obama needs him to be.

Conservative commentators and bloggers can hardly contain their glee. At the Washington Free Beacon, Matthew Continetti wrote,

We are rapidly approaching the moment at which Washington reevaluates the Obama campaign’s reputation for competence and expertise. Every week, one or several of Obama’s surrogates trip over their own words…. One gaffe is an isolated event. Two is an embarrassment. But three or more form a pattern, one that is damaging not only Obama’s precarious chances for reelection but also the fortunes of the Democratic Party.

Perhaps. In attempting to rally the base and raise money, Obama has moved from one issue to another over the past few weeks. Surely, he needs to articulate a clearer vision of where he intends to take the country and how he intends to kick-start a slowing economy. But just because Joe Biden can’t keep quiet and Corey Booker and Steve Rattner object to attacks on Romney’s record at Bain Capital, it doesn’t mean that Obama’s campaign is imploding. Biden is Biden. Seizing an early opportunity to try and define the presumptive G.O.P. candidate as an out-of-touch rich guy makes strategic sense—even if it causes some dissension in the Wall Street wing of the Democratic Party.

Much of what is happening in the media has nothing to do with the President’s I.Q., or with poor old Joe Biden, or with the missteps of David Axelrod, Jim Messina, and the rest of Obama’s campaign Rottweilers out in Chicago. It is about commentators catching up with the polling numbers and the economic data, which have been indicating for some time that this is going to be a very close race. Having largely written off Romney’s chances in the first few months of this year, the pundits now have to explain why he is suddenly leading Obama in some polls and running very close in others. One obvious, but not necessarily accurate, explanation is that Obama is screwing up.

I ran through some polling data last week. Several surveys published this week confirm it is a dangerous time to be running for reëlection. According to TPM’s poll tracker, almost two thirds of Americans still believe the country is on the wrong track, and according to the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll, more than four in five voters think the economy isn’t in good shape. Just sixteen per cent of respondents said they personally are better off than when Obama took office: thirty per cent say they are in worse shape.

In circumstances such as these, virtually any incumbent would be facing a tough reëlection race, and Obama is no exception. For several months, though, the internecine warfare of the G.O.P. primary and a sharp drop in the unemployment rate, which raised hopes that the economic slump might finally be coming to an end, obscured the picture. It is the fading of these factors, rather than any major stumbles on Team Obama’s part, that explain why Mitt Romney is smiling these days.

The Politico story gives Romney credit for focussing on the economy and playing to his strengths, but that is nothing new. He has been trying to do that all along. A few months back, when the unemployment rate was falling and things appeared to be looking up, his message that Obama doesn’t know what he is doing didn’t resonate. Now it does—even though, as I pointed out yesterday, much of what he is saying is guff. Fifty-five per cent of respondents to the ABC News/WaPo poll said they disapprove of the President’s handling of the economy—a finding that is mirrored consistently in other surveys.

Attacking Romney’s record at Bain Capital will serve to reinforce doubts about his job-creation skills. But they won’t do much to change people’s opinions of the President’s competence as an economic manager. On this front, the critics of his campaign have a point. Rather than simply targeting Romney, the White House needs to be much more forceful in defending its economic record over the past few years, and in laying out proposals to create more jobs. A good place to start would be the American Jobs Act of 2011, large parts of which the Republicans in Congress refused to pass. Here’s a little example the President should be emphasizing in speeches and campaign ads: if the G.O.P. had enacted the whole of the package, tens of thousands of teachers who were laid off by cash-strapped states would still have their positions.

All sides agree that the election will come down to the economy. If Obama pushes a coherent message on jobs and prosperity, one that combines a critique of Romney and the G.O.P. with a positive vision for his second term, the odd slipup here or there won’t matter very much—not nearly as much as how the next few months of economic statistics come in. Most voters don’t read Politico, or TPM, or follow Twitter all day. They will judge Obama based upon their overall impression of his record, and on the basis of how much they trust him compared to his rival.

On the latter point, the latest polls contain some encouraging news for the President. Americans, skeptical as they are about what he has achieved, don’t necessarily believe that the Mittster would do better. Here are two questions from the ABC News/WaPo poll:

Q: Regardless of who you support, which candidate do you trust to do a better job handling the economy?A: Obama: 46%, Romney: 47%

Q: Regardless of who you support, which candidate do you trust to do a better job creating jobs?

A: Obama: 47%, Romney 44%

It’s basically a tie. On the key issue of the race, neither candidate has the upper hand. As summer beckons, that is the real headline of the day. But, of course, it’s a lot more fun to write about campaign blunders, internal squabbling, and the rest.

May 24, 2012

Romney’s Blueprint: America Under Super-Mitt

We’ve reached the stage of the campaign in which the Mittster gets to sit down with bigfoot political journalists and talk about bigfoot political issues. No more of the trivia that dominated the primaries: this man could be the next POTUS. The latest polls show him closing on President Obama in three key battleground states, and Ladbrokes, the British bookmaker, has cut the odds on him being elected to 11/8—bet $80 to win $110. (Obama is still the 4/7 favorite.) Let’s see what he’s got to say.

First up for the Beltway clodhoppers was Mark Halperin, of Time magazine and MSNBC, who met Romney at a midtown hotel on Wednesday morning and questioned him at length about his economic proposals. Romney’s answers didn’t contain any big newsbreaks, but they clearly demonstrated that he has been sorely misrepresented. This man isn’t just a former governor, an esteemed vulture capitalist, a flip-flopper extraordinaire, a tax avoider, a former Mormon lay bishop, and a rescuer of troubled sporting events: he’s Superman.

No, really. If elected, he told Halperin, he will bring the unemployment rate down to below six per cent; persuade both parties in Congress to reach a historic agreement on taxes and spending; turn the United States into the world’s largest energy producer; overhaul the income-tax system, making it flatter and fairer; force the Chinese to behave themselves; and get the wages of middle-income Americans growing again. He didn’t say he’d accomplish these things before lunch, but that was the impression that I got. All those long afternoons in the Oval Office, President Super-Mitt will presumably spend on saving the euro, fixing global warming, and curing Alzheimer’s.

You still think I’m joking? Look at the transcript of the interview:

Halperin: Would you like to be more specific about what the unemployment rate would be like at the end of your first year?

Romney: I can’t possibly predict precisely what the unemployment rate will be at the end of one year. I can tell you that over a period of four years, by virtue of the policies that we’d put in place, we’d get the unemployment rate down to 6%, and perhaps a little lower … [T]he key is we’re going to show such job growth that there will be competition for employees again. And wages—we’ll see the end of this decline we’re having. The median income in America is down 10% in just the last four years. That’s got to stop. We’ve got to start seeing rising wages and job growth.

An unemployment rate beginning with “5”—that would be very welcome. The last time we had one was July of 2008. Today, the unemployment rate is 8.1 per cent. If the economy expands at an annual rate of three per cent or more for the next four years, it’s just about possible that we could get there. But it would take a big improvement in the economy. Last year, growth was just 1.7 per cent. (For what it’s worth, the Congressional Budget Office is projecting an unemployment rate of 6.9 per cent at the end of 2015.)

On the issue of wages and income, Romney needs to get his figures straight. The latest report from the Census Bureau shows that between 2007 and 2010, the last year for which official figures are available, median household income fell by about five per cent. The Romney campaign has previously cited income data from a private research firm, but the latest figures from their source show that between December of 2007 and March of 2012, median income fell by eight per cent, not ten per cent.

Still, eight per cent is a big drop. If Romney is merely saying that he will restore some of what was lost in that fall, he’s on defensible ground. As long as the economy keeps growing, wages and incomes will edge up a bit: they always do as a recovery matures. But if Romney is suggesting that he can solve the underlying problem of income stagnation—and that is what he appears to be doing—he is making a very big claim.

Median household income has been falling since 2000, when George W. Bush was elected. (Between 2000 and 2008, it fell by more than four per cent.) For individuals, particularly men, the problem of wage stagnation goes back a lot further than 2000. The median income of full-time male workers is lower now than it was in 1977, when Jimmy Carter was occupying the White House and Seattle Slew was winning the Triple Crown. (Here are the figures in inflation-adjusted dollars: 1977: $47,935. 2010: $47,715.) If President Romney can solve this problem, he will deserve a spot on Mount Rushmore.

How’s he going to do it? He pointed to not one policy proposal but fifty-nine—the number contained in his economic plan. “[T]he wonderful thing about the economy is that there’s not just one element that somehow makes the economy turn around,” he explained. “It’s a whole series of things.” Asked to narrow it down a bit by Halperin, Romney focussed on five things: low-cost energy (“drill-drill-drill”), labor policies (union bashing), trade policies (standing up to the Chinese), abolishing Obamacare, and easing regulations on community banks.

Ah, the long-suffering community banks. Don’t forget about them. But what of the budget crisis and the so-called “fiscal cliff”? On January 1, 2013, the Bush tax cuts are set to expire, and big spending reductions, including at the Pentagon, are due to go into effect—a combination that could well plunge the economy back into recession, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Never fear: Super-Mitt has a ready solution at hand. “My hope is to be able to come into office with people on both sides of the aisle who are cognizant of the critical nature of what America faces fiscally, what the people of America are facing employment wise, the failure in our economy that’s hurting so many people,” he said. “And that we’ll see Republicans and Democrats say, ‘O.K., what kind of tax proposals will encourage economic growth? What kind of regulatory reform will encourage economic growth?’ Energy polices, educations policies and the like. I think we can do that.”

Well, he always said he was an optimist. Why shouldn’t he succeed where Presidents of both parties have failed for thirty years? Once the Democrats and Republicans in Congress have a practical businessman rather than a former community organizer to show them the way, they will surely come up with a grand bargain that, at one stroke, solves the long-term budget crisis, stimulates economic growth, and reduces tax rates while getting rid of only those tax shelters enjoyed exclusively by the very wealthy. “Simpson-Bowles proves the math works,” Romney said. “You can get there. But the decision as to which is the area that will be limited and by how much? That’s something we’ll work with Congress to determine.”

That’s good of him. If only Obama had thought of getting the two sides together and trying to come up with a compromise on taxes and spending. But what can you expect from a President, who, as Romney put it, “while he might be a nice guy, is simply not up to the task of helping guide an economy”?

The Mittster’s clearly up to it, and not just because, as he reminded Halperin, he can read a balance sheet. Nobody’s paid much heed to it so far, but he’s come up with a fiendishly clever way to unite the country behind him, break through the political logjam, and put America back to work: he’s going to cut off the federal funding for PBS. “I like PBS,” he said. “I’d like my grandkids to be able to watch PBS. But I’m not willing to borrow money from China, and make my kids have to pay the interest on that, and my grandkids, as opposed to saying to PBS: Look, you’re going to have to raise more money from charitable organizations or from advertising.”

So there you have it, the Romney platform for 2012: jobs and wage increases for all, cheap gas, a chastised China, peace and harmony on Capitol Hill, and round-the-clock pledge drives on PBS that stop once a week for the latest episode of “Downton Abbey”—with commercials.

Does that sound all bad?

Photograph by Brian Blanco/The New York Times/Redux.

May 23, 2012

Facebook Fiasco: Don’t Leave It To the Lawyers

If you were thinking of advising your nephew or niece to go into software programming, think again. The hours are long, there’s a lot of competition from Europe and the sub-continent, and for every Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates there are tens of thousands of modestly remunerated back-office grunts. Lawyers, on the other hand, tend to win every which way: just ask M.Z., who, so far, must be finding his twenty-ninth year rather trying.

Zuckerberg’s torture-by-attorney didn’t start in the past twenty-four hours, when law firms in New York and California initiated the first of what is sure to be a slew of lawsuits related to last week’s controversial I.P.O. Ever since February, when Facebook filed its initial investment prospectus, the youthful C.E.O. has had to check with his own lawyers before saying virtually anything publicly—a requirement imposed as part of the S.E.C.’s pre-I.P.O. “quiet period,” which applies to any company preparing to issue stock. Now, Zuckerberg finds himself in another spell of S.E.C. imposed omertà—a forty-day post-I.P.O. quiet period. Because of this requirement, Facebook’s lawyers and outside counsel will be telling him he can’t respond publicly to allegations from other lawyers that he and his cohorts on Wall Street have just diddled the public to the tune of many billions of dollars.

Zuckerberg already has more than one set of lawyers to worry about—so many are targeting his company, in fact, that it’s hard to keep count. There is the eminent ambulance-chasing firm of—sorry, make that eminent investor-protection firm of—Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd, whose list of past targets includes Enron, WorldCom, and Wachovia. This morning, the firm, which is based in San Diego, filed suit in a New York federal court, alleging that Facebook and its I.P.O. underwriters issued “false and misleading” information to investors ahead of last Friday’s stock issue. Yesterday, the Los Angeles-based firm of Glancy Binkow & Goldberg filed a similar piece of paper in California state court.

Both suits claim that, based upon information supplied by Facebook, analysts at Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and J. P. Morgan cut their revenue forecasts for the company shortly before the I.P.O., but that this information was not passed on to ordinary investors. “The main underwriters in the middle of the road show reduced their estimates and didn’t tell everyone,” Samuel Rudman, a partner at Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd, said. “I don’t think any investor in Facebook wouldn’t have wanted to know that information.”

If Mr. Rudman or any of his colleagues are looking to depose Zuckerberg and David Ebersman, Facebook’s chief financial officer, who helped orchestrate the I.P.O., they will have to get in line. Before dealing with the private lawsuits, the Facebook duo, or their representatives, will almost certainly be hauled before some government lawyers to explain themselves. On Tuesday, Mary Schapiro, the head of the S.E.C., confirmed that the agency is investigating the Facebook I.P.O., saying “there are issues that we need to look at.” Members of the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee said that they, too, are examining the matter, which almost certainly means there will be public hearings. “Effective capital markets require transparency and accountability, not one set of rules for insiders and another for the rest of us,” said Sherrod Brown, the Democratic senator from Ohio who chairs the Senate Banking Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection.

And just in case the feds haven’t got it adequately covered, William Galvin, the crusading Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, has issued a subpoena to Morgan Stanley, which will doubtless be followed by similar demands upon the other underwriters and Facebook itself. (For years now, Galvin has been following the example of Eliot Spitzer and using state law to go after Wall Street malfeasance.)

Put it all together, and it’s almost enough to make me feel sorry for Zuckerberg and his colleagues—almost, but not quite. As I said the other day, the I.P.O. looked suspiciously like an inside job. By delaying going public until speculation in the “gray market” had pushed its valuation up to an astronomical level, and then by pressing the underwriters to raise the issue price and expand the number of shares on offer, Facebook largely brought this fiasco upon itself. But before we start hauling people into court, let’s be clear about what the real issues are.

The simple fact that investors have lost money isn’t one of them. When Americans called up their brokers and placed orders for Facebook, they knew, or should have known, that they were making a very speculative investment, which could well turn out badly. Anybody who took the trouble to read the prospectus could see that the company’s growth was slowing and that its costs were rising faster than its revenues. Anybody who didn’t bother to read the prospectus shouldn’t have been buying shares in the first place.

That doesn’t mean Facebook and the underwriters disclosed all they should have. If Facebook, in the days and weeks leading up to the I.P.O., had explicitly told analysts at Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and J. P. Morgan that rising mobile usage was crimping its revenue growth—it hasn’t yet found a way to effectively serve ads to mobile users—this should have been disclosed clearly. Whether such a disclosure would have made much difference to how the I.P.O. turned out is not the point. (For what it’s worth, I doubt it would have.) The point is that a company’s assessment of how its revenue is growing is clearly material to its valuation, and it should have been widely disseminated. Ultimately, then, the lawsuits will probably come down to two questions: Did Facebook reveal sufficient detail about the mobile-usage issue in its May 9th amendment to its prospectus? And did Morgan Stanley, or any other underwriter, issue guidance based upon non-public information to some investors—the firm’s favored clients—but not others?

Answering these questions will keep the lawyers busy and their children well fed. But to reiterate what I said in my previous post, the larger and more important issue is the manner in which technology I.P.O.s—not just Facebook’s—are organized these days, and particularly the proliferation of late-stage fund-raising rounds that start-ups and their venture-capital backers use to up their valuation and retain most of the wealth for themselves. As long as they don’t, in that process, violate the rule that private companies keep their total number of outside investors below five hundred, they don’t violate any laws, but they do change the nature of I.P.O.s.

The old I.P.O. system wasn’t perfect either: far from it. As a commenter on my last post pointed out, insiders received much of the spoils then, too, but they were a different set of insiders—the favored clients of Wall Street firms, who were given access to “hot” deals as a reward for their regular business. Many of these insiders bought the stock and flipped it a few days later, a practice that doesn’t appear to serve much public purpose. At the same time, though, the prospect of a “pop” in I.P.O. stocks drew in investors and made it easier for other companies to go public.

There are pluses and minuses to any system. Clearly, though, the Facebook I.P.O. has highlighted some significant and hitherto ignored dangers with the way the Silicon Valley-Wall Street ecosystem is heading. And that, I think, is well worth discussing in public venues other than courtrooms—such as Congressional hearing rooms.

Photograph by Scott Eells/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

May 21, 2012

Obama Doubles Down on Bain Capital Attacks

Press conferences following NATO summits aren’t usually associated with significant moments in Presidential campaigns, but the comments that President Obama made in Chicago on Monday afternoon about Mitt Romney and Bain Capital may well prove to be an exception. After weeks of jabbing between the campaigns about cultural issues that will probably play a marginal, if still significant, role in determining the election—gay marriage, abortion, and so on—the President squared up to his rival on what he hopes to make a defining issue in the fall: Romney’s record as a businessman, and how it relates to his claim to be an economic savior.

Facing criticisms from some within his own party, notably Newark mayor Cory Booker and former auto czar Steve Rattner, about a new campaign ad that accuses Romney and Bain of closing down a Kansas City, Missouri, steel mill and ruthlessly abandoning its workers to their fate, Obama used the press conference to defend the focus on Bain. Asked by Hans Nichols, of Bloomberg News, about the comments from Booker and Rattner, and about his view of private equity more generally, Obama gave a lengthy reply that is worth reading (or watching) in full. Here it is:

Well, first of all, I think Corey Booker is an outstanding mayor. He’s doing great work in Newark and obviously helping to turn that city around.

And I think it is important to recognize that this issue is not a, quote, distraction. It is part of the debate we are going to be having in this election campaign about how do we create an economy where everybody, top to bottom, on Wall Street and on Main Street, had a shot at success—and if they work hard, and they are acting responsibly, that they are able to live out the American dream.

My view of private equity is that it is, it is set up to maximize profits and that is a healthy part of the free market, of course. That’s part of the role of a lot of business people. That is not unique to private equity. My representatives have said repeatedly and I will say today, I think there are folks who do good work in that area and there are times where they identify the capacity for the economy to create new jobs or new industries. But understand their priority is to maximize profits, and that is not always going to be good for communities or businesses or workers.

And the reason this is relevant to the campaign is that because my opponent, Governor Romney, the main calling card for why he should be President is his business experience. He is not going out there touting his experience in Massachusetts, he is saying, “I am a business guy and I know how to fix it,” and this is his business.

And when you are President as opposed to the head of a private-equity firm, then your job is not simply to maximize profits. Your job is to figure out how everybody in the country has a fair shot. Your job is to think about those workers who get laid off, and how are we paying for their retraining. Your job is to think about how those communities can start creating new clusters, so that they can attract new businesses. Your job as President is to think about how do we set up an equitable tax system so that everybody is paying their fair share, that allows us then to invest in science and technology and infrastructure, all of which are going to help us grow.

And so if your main argument for how to grow the economy is, “I knew how to make a lot of money for investors,” then you are missing what this job is about.

It doesn’t mean you weren’t good at private equity, but that’s not what my job is as President. My job is to take into account everybody, not just some. My job is to make sure the country is growing not just now, but ten years from now, twenty years from now. And so, to repeat, this is not a distraction. This is what this campaign is going to be about: What is a strategy for us to move this country forward in a way where everybody can succeed? And that means I have to think about those workers in that video just as much as I’m thinking about folks who have been much more successful.

A few things immediately stand out to me. Obviously, Obama was prepared for the question. He was determined use this occasion to slap down the Booker/Rattner critique, which would place attacks on Bain out of bounds. The reason he felt this was necessary is also pretty clear. The President and his strategists have fixed upon a populist campaign strategy that emphasizes inequality and unfairness, and which attempts to turn Romney, with his record as a “vulture capitalist” and his fourteen per cent tax rate, into the personification of these things. When Obama said “this is what this campaign is going to be about,” he wasn’t joking.

Secondly, Obama is clearly trying to convert the election from a referendum on his own record to a personality contest between him and Romney. If I were in his shoes, I would be doing the same thing. As Paul Begala pointed out in a column at the Daily Beast this morning, he doesn’t have much choice. Anti-incumbent fervor is running high worldwide, and Obama’s approval ratings are worryingly low. In such circumstances, the logical thing to do is open fire on your opponent and hope you can mimic George W. Bush’s 2004 victory over John Kerry.

Not that Obama doesn’t have a good point about Romney’s experience at Bain—he does. Running a private-equity firm is a narrow pursuit, which rewards the bloodless and the single-minded. It isn’t the job of private-equity partners to torment themselves about the wider consequences of their actions, and Romney, from what we know, was anything but tormented about Bain Capital’s business model. It is perfectly legitimate to question whether he has what it takes to be President, just as it is perfectly legitimate for Romney to pose the same question about Obama.

Finally, Obama is trying to straddle a fine line. Rather than attacking private equity per se, which would delight some elements of his base, he is acknowledging that “there are folks who do good work in that area” but making the argument that running a firm like Bain is a poor preparation for being President. Since Obama recently attended a fund-raiser organized by a senior executive at the biggest private-equity firm in the country (Tony James, president of the Blackstone Group), it is hardly surprising that he would have some good things to say about the business. But as the months go on, and the practices of private-equity firms receive even more attention, it will be interesting to see how far he pushes a critique of the industry as a whole.

If the President was really serious about cracking down this form of “vulture capitalism”—thanks again to Rick Perry for popularizing this phrase—he would surely be emphasizing specific remedies, such as eliminating the grotesque “carried-interest deduction,” which allows private-equity partners to pay such a low tax rate, and limiting the tax deductibility of interest payments on the debts that firms like Bain Capital pile upon firms they acquire. At various times over the past four years, Obama has come out in favor of the first proposal, but he has never made it a top legislative priority. By the time the summer is out, he may well have done so, and he may even have embraced the second idea, too. But so far I haven’t heard him discuss it at all.

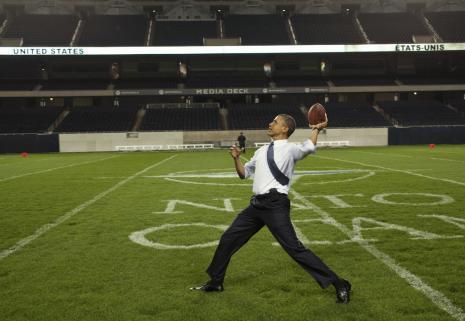

Photograph: Obama at Soldier Field after a NATO working dinner in Chicago. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

Inside Job: Facebook I.P.O. Shows System Is Broken

Monday morning’s big fall in Facebook’s stock hardly came as a shocker. It was clear on Friday that, at the offering price of $38 a share, there were more sellers than buyers. The only reason the stock held up was that Morgan Stanley, the lead underwriter on the initial public offering, stepped in and supported it. At the opening of trading this morning, the stock fell $5, to $33, before rebounding a bit. (At 2:30 P.M., it was at $34.75.)

That’s bad news for investors who thought their luck was in when they were allocated some Facebook stock. It’s also worrying news for I.P.O.s and the capital markets in general. In fact, a strong argument can be made that Facebook’s shaky start as a public company demonstrates that the entire I.P.O. process, which is supposed to spread the rewards to innovation, is broken. By the time Facebook’s stock started trading on the public market, insiders—the company’s founders, employees, and venture-capitalist backers—had bagged most, if not all, of the company’s value for themselves.

That’s fair enough, you may say. Mark Zuckerberg and some Harvard pals created the company. It was Facebook’s professional managers, such as Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer, and David Ebersman, the chief financial officer, who turned it into a real business. And it was some savvy venture capitalists, such as Jim Breyer of Accel Partners, and David Sze of Greylock Partners, who first spotted its potential. Surely, these are the folks who should be rewarded. (Bono’s investment, which my colleague , also falls into the reasonably early category. In April, 2010, Elevation Partners, a venture-capital firm in which Bono is a partner, paid ninety million dollars for one per cent of Facebook.)

Up to a point, I would agree with you. But the I.P.O. system only works if it preserves a balance between public and private investors. If this balance is upended, and virtually all of the rewards are reserved for insiders, ordinary investors will refuse to play the game. A dearth of I.P.O.s would hurt insiders along with everybody else. More important, a time-tested system of financing companies, which rewards innovation and makes Silicon Valley the envy of the world, would be destroyed.

Traditionally, I.P.O.s provided early-stage technology companies with cash to finance their expansion. They also allowed early investors, the founders included, to extract some cash. Public investors, in return for bearing considerable risk, got the opportunity to share some of the wealth these companies created. Investors who bought into companies such as Amazon.com, Apple, and Google at the beginning and stuck with them saw their investments double many times over. In the case of Facebook deal, and in several I.P.O.s that preceded it, such as those involving Zynga and Groupon, ordinary investors were largely cut out of the wealth-creation process, and well-connected investment firms took their place.

The fact is, Facebook’s I.P.O. wasn’t really an “initial” stock offering. In December, 2010, Goldman Sachs raised $500 million for the company in a deal that, following objections from the Securities and Exchange Commission, was limited to overseas investors. In the I.P.O. world, these late-stage quasi-public offerings are called “D-rounds,” and they are becoming increasingly common. Zynga did one before its I.P.O., and so did Groupon. They provide a cashing-out opportunity for insiders who would rather not wait until the I.P.O. More to the point, they allow “hot” companies to bid up the price of their stocks well before the investing public gets a sniff.

Groupon’s D-round, which raised $950 million in January, 2011, valued the company at close to $5 billion. (It is now valued at $8 billion.) The Goldman offering for Facebook valued the company at $50 billion. (It is now valued at about $95 billion.) The valuations put on the companies in these deals were quickly reflected in the so-called “gray market,” where investors in the know could buy and sell the firms’ stocks well before they started trading on the open markets. Now that Facebook’s stock is trading publicly, many of the early players have already sold out, taking a handsome profit.

How will the public investors fare? So far, they aren’t doing well, but it is still early. I said the other day that Facebook isn’t necessarily a bubble stock, but it is undoubtedly a very expensive one. Buyers are bearing a lot of risk, and it is hard to see them ever reaping the sort of returns that investors in companies like Amazon and Google enjoyed. At twenty-five times trailing revenues and a hundred times trailing earnings, the $38 I.P.O. is already discounting an awful lot of expansion—and this at a time when Facebook’s growth rate has already slowed.

Maybe I am a grouch. But it all sounds suspiciously like an inside job, in which the last ones in, the ordinary investors, are the saps. (In this week’s magazine, James Surowiecki highlights another way in which the I.P.O. favored insiders.) At the very least, this entire issue is something that the authorities—the S.E.C., but also the Nasdaq and other stock exchanges—should be looking at closely.

Photograph by Scott Eells/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers